Leadership Talent: A Study of the Potential of People in the Australian Rail Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The CRC Initiative

2. Objective and Aim of the Study

- What is your role as a leader in this organization and your particular skills and talents in leading others?

- Who is a leader that you have admired at work and what are their talents for leading others?

- What talents should be now be considered as important for “good” leaders in rail organizations?

3. Leadership Talent Literature

- What is talent?

- What is leadership?

- How is leadership talent defined?

- Why focus on leadership talent?

- What conditions influence talented leaders?

- How do leaders become talented?

3.1. What Is Talent?

3.2. What Is Leadership?

3.3. How Is Leadership Talent Defined?

3.4. Why Focus on Leadership Talent?

3.5. What Conditions Influence Talented Leaders?

3.6. How do Leaders Become Talented?

3.7. What Are the Effects of Talented Leaders and Leadership?

3.8. Reflections on the Literature

4. Method

4.1. Interpretivism

4.2. Research Design

| Organization A | Organization B | Organization C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Service | Passenger services including train, bus and ferry and infrastructure maintenance and development | Track infrastructure and train control (dispatch) services in remote Australia | Passenger rail services in metropolitan area |

| Sectoral representation | Public sector | Private Sector | Public/Private partnership |

| Location (city and rural) | City and rural | City and rural | City |

| Size (staff numbers) | 1463 | 238 | 3700 |

5. Findings and Discussion

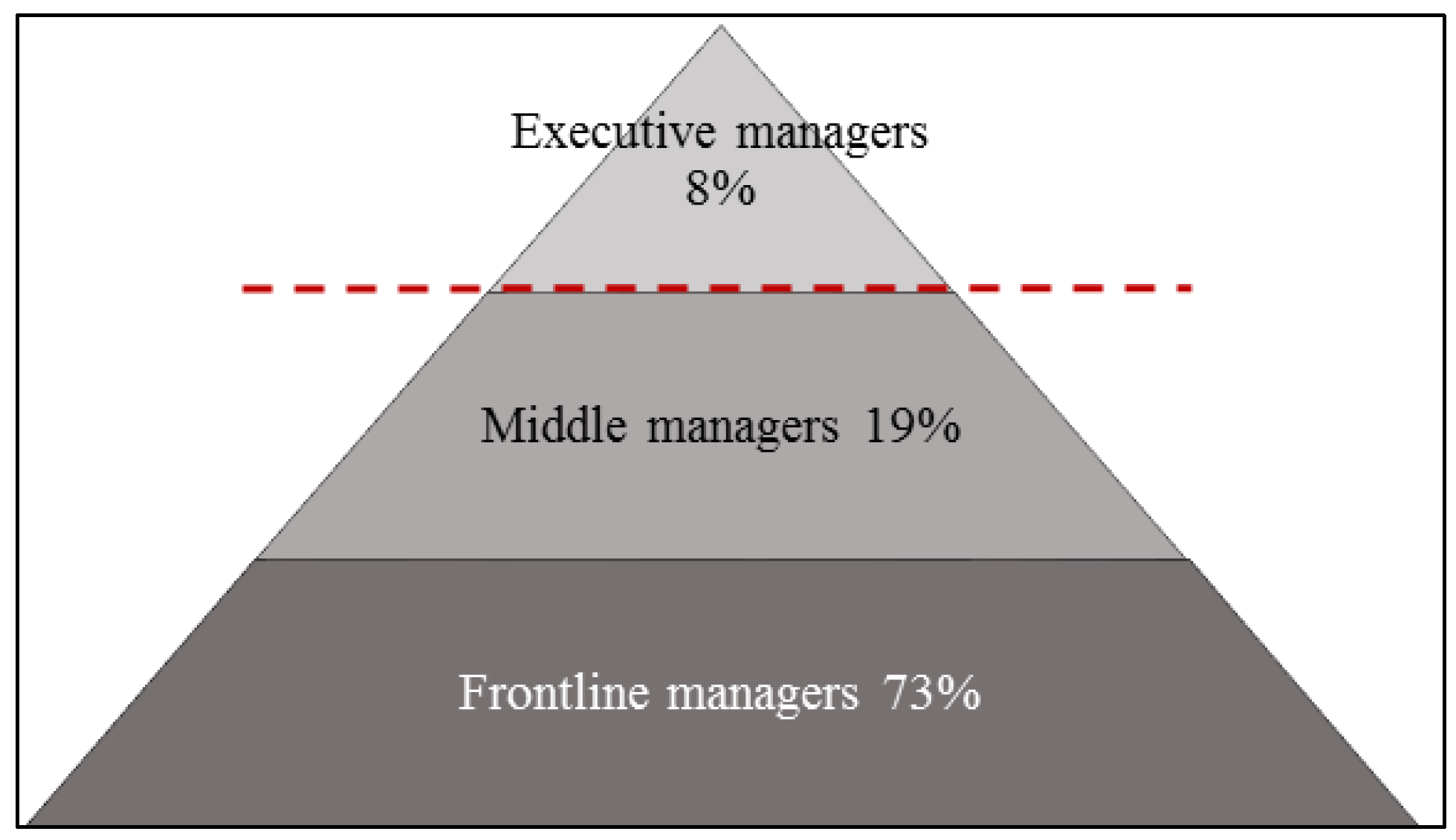

5.1. Background

5.2. What Is Leadership Talent?

I’m certainly not aware of one in the sense of do we have a bit of paper which says here’s what we want from leaders and we’re going to try and identify people who have those particular attributes or skill sets and do we communicate that? No. I’ve certainly never seen that written down on a bit of paper… (Executive leader, Organization A, male).

5.3. What Is Your Role as a Leader and the Way You View the Skills Required to Lead Ohers?

I think that leadership is about leadership rather than managing and it’s about building teams; about building relationships with people who lead those teams and setting the appropriate examples and that extends to our contractors also. There’s a vast difference between managing—situations can be managed, people need to be led, and I think that at the executive level one needs to recognize that leadership takes precedence over management (Executive leader, Organization B, male).

I think a good leader takes people with them rather than pushes or coerces them. I think good leaders that I’ve seen are very clear on the goals and targets they want to achieve and they communicate that with their people both widely and also on a personal basis (Executive leader, Organization B, male).

I think he’s got very good interpersonal skills. Besides the fact that he’s the boss, he is happy to talk to anybody...he remembers that sort of stuff and raises it with people…always very impressed with that, so I think it’s the common touch...(Executive leader, Organization A, male).

Well, I have worked for the organization for 35 years and I’ve just gone up through the ranks—through the organization doing different jobs from time to time; different locations; different types of jobs and positions and I’ve just moved into this role you might say (Middle leader, Organization B, male).

I started out as a junior locomotive operator…I got my experience up…moved to a team leader role…went to Train Control…learnt the role over a number of years…then I was given a golden opportunity…to middle leader (Middle leader, Organization B, male).

Up and down—I’ve been up and down the ladder a few times for different restructures, changes of management predominantly—I would say probably 15 years I guess in total, perhaps a little bit longer…(Middle leader, Organization C, male).

If the decision didn’t go in a particular person’s favor, she would explain the reasons why these didn’t go in, this is why and this is the decision that it was made on these merits…If there was something that needed to be done that was tough to tackle on an individual issue, then she would do it discreetly as necessary and move on… (Middle leader, Organization A, male).

An authorized officer…everyone calls them ticket inspectors…they’re responsible for a number of different jobs—it’s customer service; it’s enforcing the law under the Transport Act, and we get involved in crowd control for football traffic, special events…(Frontline leader, Organization C, male).

You can’t make a promise that you can’t keep, and you’ve got to walk the walk—if you are asking someone to be this or do that, you have to do it too. You can’t ask someone to do something if you’re not going to do it yourself (Frontline leader, Organization C, male).

He’s a person that allows you freedom to do what you need to do, but he does give you the guidelines within which to work, so he basically sets the boundaries and then allows you to proceed and to develop within those boundaries. I think that’s good leadership skills (Frontline leader, Organization B, male).

5.4. How do Leaders Become Talented?

We’re starting to identify individuals but from the perspective of identifying future leaders is actually critical because we don’t have enough at the moment, and you then need to mentor and develop them to the point where they can actually then assume a leadership role, so this all takes time… (Executive leader, Organization C, male).

Certainly, you might amongst your management ranks to say get a bit more rigor into it but in terms of train drivers—the vast majority just wishes to remain driving trains and that’s a pointless exercise (Executive leader, Organization A, male).

I’ve been in the Railways since 1988, and I started as a junior admin officer at a bus depot and just over the years I have just sort of worked my way through the different areas and opportunities came up and I never actually had to apply for any of the positions I have been in. I have always been asked “Do you want to do this? Do you want to do that?” and it’s just progressed from there till I have got to this point where I am at now (Frontline leader, Organization C).

Usually very easily identified—people in this organization are people who have either been here a long time or come in from outside, and some of them have very strong talents in some areas because they’ve come from those areas, and some have a bit of a broad talent... (Frontline leader, Organization A).

5.5. What Talents Should Now Be Considered as Important for “Good” Leaders in Rail Organizations?

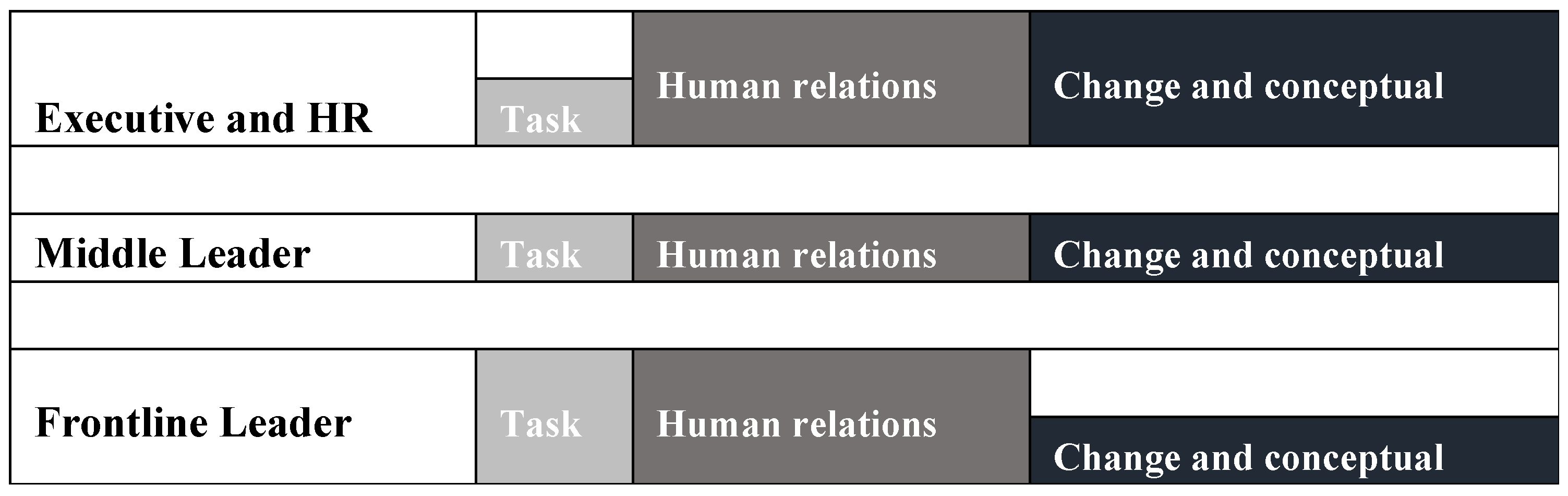

| Task | Human Relations | Change and Conceptual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Executive | Develop performance and behavioural benchmarks for the organisation Use technology to facilitate business, communication and ways of working | Understand personal communication style and impact on others at strategic, team and personal levels Develop skills in “personal” and one-on-one performance conversations Build relationships up and down the organisation Use and endorse contemporary learning approaches to leadership development Actively seek feedback about own performance | Develop an understanding of global rail industry environment and trends and parent company strategy Communicate appropriate messages about company direction for different levels of the organisation |

| Middle | Gain formal qualifications in either vocational and/or higher education disciplines such as safety, engineering, finance or other to develop career | Develop skills in “personal” and one-on-one performance conversations Discuss personal career aspirations with teams Understand different approaches to developing leaders | Be open to new career experiences and ways of conducting business based on global trends Develop IT skills to facilitate work more efficiently |

| Frontline | Develop skills in managing resources and people Participate in formal training to gain a different perspective on how other industries manage and lead people | Develop skills in “personal” and one-on-one performance conversations Discuss personal career aspirations with teams Take time to consider how work impacts people in demanding roles | Take action to remedy issues you have the ability to fix |

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CRC for Rail Innovation. “Welcome to the CRC for Rail Innovation.” Available online: http://www.railcrc.net.au/ (accessed on 2 February 2013).

- Australasian Railway Association Inc. A Rail Revolution: Future Capability Identification and Skills Development for the Australasian Rail Industry. Kingston: Australasian Railway Association, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Michelle Wallace, Ian Lings, Neroli Sheldon, and Roslyn Cameron. “Attraction and image for the australian rail industry.” In Paper presented at British Academy of Management Conference, Sheffield, UK, 14–16 September 2010.

- Anusha Mahendran, Alfred Michael Dockery, and Fred Affleck. Forecasting Rail Workforce Needs: A Long-Term Perspective. Perth: Centre for Labour Market Research, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tim Brennan, Nick Wills-Johnson, Paul Larsen, Anusha Mahendran, Brett Hughes, and Jian Wang. “The business of australia’s railways: Proceedings from the australian railways business and economics conference.” In Proceedings of Australian Railways Business and Economics Conference, Australia, 20 July 2009; Edited by Nick Wills-Johnson. Perth: Centre for Research in Applied Economics, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PWC). The Changing Face of Rail: A Journey to the Employer of Choice. Canberra: Australasian Railway Association (ARA) Inc., 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Renu Agarwal, and Roy Green. “The role of educational skills in australian management practice and productivity.” In Fostering Enterprise: The Innovation and Skills Nexus—Research Readings. Edited by Penelope Curtin, John Stanwick and Francesca Beddie. Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Education Research, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth G. Chambers, Mark Foulon, Helen Handfield-Jones, Steven M. Hankin, and Edward G. Michaels. “The war for talent.” The McKinsey Quarterly 3 (1998): 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ed Michaels, Helen Handfield-Jones, and Beth Axelrod. The War for Talent. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- John W. Boudreau, Peter M. Ramstad, and Peter J. Dowling. “Global talentship: Toward a decision science connecting talent to global strategic success.” Advances in Global Leadership 3 (2003): 63–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Busine, and Bruce Watt. “Succession management: Trends and current practice.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 43 (2005): 225–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas N. Garavan, Ronan Carbery, and Andrew Rock. “Mapping talent development: Definition, scope and architecture.” European Journal of Training and Development 36 (2012): 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh Scullion, and David Collings. “Global talent management.” Journal of World Business 45 (2010): 105–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maura Sheehan. “Developing managerial talent: Exploring the link between management talent and perceived performance in multinational corporations (mncs).” European Journal of Training and Development 36 (2012): 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Richard A. Swanson, and Elwood F. Holton. Foundations of Human Resource Development, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Clardy. “The strategic role of human resource development in managing core competencies.” Human Resource Development International 11 (2008): 183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carole Tansley. “What do we mean by the term ‘talent’ in talent management? ” Industrial and Commercial Training 43 (2011): 266–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard E. Boyatzis. “Competencies in the 21st century.” Journal of Management Development 27 (2008): 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard E. Boyatzis. “Managerial and leadership competencies.” Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective 15 (2011): 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Kegan, and Lisa Lahey. Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Cambridge: Harvard Business Press, 2009, p. xvii, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Kegan, and Lisa Lahey. “Adult development and organisational leadership.” In Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice: An Harvard Business School (hbs) Centennial Colloquium on Advancing Leadership. Edited by Nitin Nohria and Rakesh Khurana. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford D. Smart. Topgrading: How Leading Companies Win by Hiring, Coaching, and Keeping the Best People. Paramus: Prentice Hall Press, 1999, p. xi, 403. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony McDonnell. “Still fighting the ‘war for talent’? Bridging the science versus practice gap.” Journal of Business and Psychology 26 (2011): 169–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman Aguinis, Ryan K. Gottfredson, and Harry Joo. “Using performance management to win the talent war.” Business Horizons 55 (2012): 609–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter Stahl, Ingmar Björkman, Elaine Farndale, Shad S. Morris, Jaap Paauwe, Philip Stiles, Jonathan Trevor, and Patrick Wright. “Six principles of effective global talent management.” MIT Sloan Management Review 53 (2012): 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Thompson, and Jane Brodie Gregory. “Managing millennials: A framework for improving attraction, motivation, and retention.” Psychologist-Manager Journal 15 (2012): 237–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter G. Northouse. Leadership: Theory and practice, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard M. Bass, and Ruth Bass. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. New York: The Free Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keith Grint. “A history of leadership.” In The Sage Handbook of Leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., 2011, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy Papalexandris, and Eleanna Galanaki. “Connecting desired leadership styles with ancient greek philosophy: Results from the globe research in greece, 1995–2010.” In Leadership through the Classics. Berlin: Springer, 2012, pp. 339–50. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Carlyle. On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Francis Galton. Hereditary Genius. New York: Appleton, 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick Winslow Taylor. The Principles of Scientific Management. New York: Norton, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Robert R. Blake, Jane S. Mouton, and Alvin C. Bidwell. The Managerial Grid. Houston: Gulf, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Fred Edward Fiedler, and Martin M. Chemers. A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- James M. Burns. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- James M. Kouzes, and Barry Z. Posner. The Leadership Challenge—How to Get Extraordinary Things Done in Organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mary Uhl-Bien, Russ Marion, and Bill McKelvey. “Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era.” The Leadership Quarterly 18 (2007): 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald D. Snee, and Roger W. Hoerl. “Leadership—Essential for developing the discipline of statistical engineering.” Quality Engineering 24 (2012): 162–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy V. Mumford, Michael A. Campion, and Frederick P. Morgeson. “The leadership skills strataplex: Leadership skill requirements across organizational levels.” The Leadership Quarterly 18 (2007): 154–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Lee Katz. “Skills of an effective administrator.” Harvard Business Review 33 (1955): 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Michael D. Mumford, Stephen J. Zaccaro, Mary Shane Connelly, and Michelle A. Marks. “Leadership skills: Conclusions and future directions.” The Leadership Quarterly 11 (2000): 155–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert W. Eichinger, and Michael M. Lombardo. “Learning agility as a prime indicator of potential.” People and Strategy 27 (2004): 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Linda E. Morris, and Christine R. Williams. “A behavioral framework for highly effective technical executives.” Team Performance Management 18 (2012): 210–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas Clarke. “Model of complexity leadership development.” Human Resource Development International 16 (2013): 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine Boedker, Richard Vidgen, Kieron Meagher, Julie Cogin, Jan Mouritsen, and Mark Runnalls. Leadership, Culture and Management Practices of High Performing Workplaces in Australia: Literature Review and Firm Diagnostics. Sydney: The Society for Knowledge Economics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jean-François Lyotard. Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1984, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Charles B. Handy. Beyond Certainty: The Changing Worlds of Organizations. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- David Ashton, Phillip Brown, and Hugh Lauder. Education, Globalisation and the Knowledge Economy (Teaching and Learning Research Programme). London: University of London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel Castells. The Rise of the Network Society: The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2011, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nicky Dries. “The meaning of career success.” Career Development International 16 (2011): 364–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraiz Tarique, and Randall S. Schuler. “Global talent management: Literature review, integrative framework and suggestions for further research.” Journal of World Business 45 (2010): 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvin Toffler. The Third Wave. New York: Bantam Books, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rob Silzer, and Allan H. Church. “The pearls and perils of identifying potential.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2 (2009): 377–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary Yukl, Angela Gordon, and Tom Taber. “A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: Integrating a half century of behavior research.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 9 (2002): 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Hooijberg, James G. Jerry Hunt, and George E. Dodge. “Leadership complexity and development of the leaderplex model.” Journal of Management 23 (1997): 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa A. Boyce, Stephen J. Zaccaro, and Michelle Zazanis Wisecarver. “Propensity for self-development of leadership attributes: Understanding, predicting, and supporting performance of leader self-development.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (2010): 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen Swailes. “The ethics of talent management.” Business Ethics: A European Review 22 (2013): 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael J.A. Howe, Jane W. Davidson, and John A. Sloboda. “Innate talents: Reality or myth.” Behavioural and Brain Sciences 21 (1998): 399–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herminia Ibarra, Scott Snook, and Laura Guillen Ramo. “Identity-based leader development.” In Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice. Edited by Nitin Nohria and Rakesh Khurana. Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2010, p. 674. [Google Scholar]

- Christiana Houck. “Multigenerational and virtual: How do we build a mentoring program for today.” Performance Improvement 50 (2011): 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean Piaget. Biology and Knowledge: An Essay on the Relations between Organic Regulations and Cognitive Processes. Translated by Beatrix Walsh. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971, p. xii, 384. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Piaget. The Origin of Intelligence in the Child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1953, p. xii, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Kegan. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Kegan. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Karen Eriksen. “The constructive developmental theory of robert kegan.” The Family Journal 14 (2006): 290–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessica Traylor. “Robert kegan’s constructive-developmental theory—Orders of consciousness.” Available online: http://www.slideshare.net/JessicaTraylor/kegan-constructive-developmental-theory (accessed on 14 March 2012).

- Dawn E. Chandler, and Kathy E. Kram. “Applying an adult development perspective to developmental networks.” Career Development International 10 (2005): 548–66. [Google Scholar]

- Grady McGonagill, and Peter W. Pruyn. “Leadership Development in the US: Principles and Patterns of Best Practice.” Available online: http://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/cps/rde/xbcr/SID-7F606111-03CADE44/bst/Bertelsmann%20Foundation-%20Leadership%20Development%20in%20the%20US%20-%20Principles%20and%20Patterns%20of%20Best%20Practice.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2011).

- David V. Day, Michelle M. Harrison, and Stanley M. Halpin. An Integrative Approach to Leader Development: Connecting Adult Development, Identity, and Expertise. London: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Lave, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- David V. Day, and Michelle M. Harrison. “A multilevel, identity-based approach to leadership development.” Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007): 360–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davide Orazi, Laura Good, Mulyadi Robin, Brigid van Wanrooy, Ivan Butar, Jesse Olsen, and Peter Gahan. Workplace Leadership: A Review of Prior Research. Melbourne: Centre for Workplace Leadership, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tom W. Short, Janene K. Piip., Tom Stehlik, and Karen Becker. A Capability Framework for Rail Leadership and Management Development. Brisbane: CRC for Rail Innovation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Michael D. Myers. Qualitative Research in Business and Management. London: Sage Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A. Maxwell. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kirrilly Thompson. “Qualitative research rules: Using qualitative and ethnographic methods to access the human dimensions of technology.” In Evaluation of Rail Technology: A Practical Human Factors Guide. Edited by Anjum Naweed, Jillian Dorrian, Janette Rose, Drew Dawson and Chris Bearman. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013, pp. 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- John W. Creswell. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among the Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deborah Cohen, and Benjamin Crabtree. “Qualitative research guidelines project.” July 2006. Available online: http://qualres.org/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2010).

- Peter L. Berger, and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City: Doubleday, 1966, p. x, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Clardy. Studying Your Workforce: Applied Research Methods and Tools for Training and Development Practitioners. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robert K. Yin. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maureen Jane Angen. “Evaluating interpretive enquiry: Reviewing the validity debate and opening the dialogue.” Qualitative Health Research 10 (2000): 378–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piip, J. Leadership Talent: A Study of the Potential of People in the Australian Rail Industry. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 718-741. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030718

Piip J. Leadership Talent: A Study of the Potential of People in the Australian Rail Industry. Social Sciences. 2015; 4(3):718-741. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030718

Chicago/Turabian StylePiip, Janene. 2015. "Leadership Talent: A Study of the Potential of People in the Australian Rail Industry" Social Sciences 4, no. 3: 718-741. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030718

APA StylePiip, J. (2015). Leadership Talent: A Study of the Potential of People in the Australian Rail Industry. Social Sciences, 4(3), 718-741. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030718