1. Introduction

The rise of social media has reshaped the global landscape of knowledge. Easy access to digital information and the growth of online platforms have changed how people search for, share, and engage with knowledge. These changes have had a major impact on genealogy—the study of family history—which now attracts millions worldwide seeking to reconstruct their family narratives (

Davison 2009).

In the past, genealogical research was mostly limited to professional historians and elite families (

Willever-Farr 2017). It required costly travel to distant archives and access to rare documents, making it inaccessible to most. The digital revolution changed this reality. Online databases, commercial genealogy platforms, and DNA technologies have made genealogical research more affordable and widely available (

Liew et al. 2022). At the same time, social media has enabled the growth of online communities focused on family history (

Charpentier and Gallic 2020).

This study was based on interviews with 15 Facebook community managers. It shows that these communities act as important knowledge hubs. They support information exchange and help build shared genealogical understanding.

Community managers play a central role. They combine technological skills, historical knowledge, and information management. Their work is especially meaningful in communities shaped by historical trauma. These managers are more than data organizers: they are guardians of collective memory. They help preserve and restore both family and communal heritage.

The research examined how online genealogical communities function as centers of knowledge. It also explored the role of community managers as key mediators. By analyzing their self-perception and how they are viewed by others, the study highlights their growing importance in today’s genealogical information ecosystem.

2. Literature Review

This literature review examines the evolution of genealogy and the transformations in its information ecology across three centuries, with particular emphasis on the substantial developments of the past three decades.

The term “genealogy” derives from the conjunction of two Greek words:

genea, signifying “generation” or “family,” and logos, denoting “knowledge” or “study” (

Online Etymology Dictionary 2023). The term shares etymological roots with related concepts like genesis, genetics, generation, genome, generator, and gender, underscoring its fundamental connection to origins, development, and heredity.

Genealogy constitutes a field of systematic research of families, their histories, and their lineages, wherein individuals with shared interests or cultural backgrounds collaborate to achieve optimal outcomes (

Yakel 2004). The genealogical process encompasses root discovery and lineage tracing through documentary analysis. This process synthesizes historical, social, communal, geographical, and cultural information, transforming empirical findings into coherent biographical narratives.

Genealogical research facilitates comprehensive understanding of ancestral origins and lifestyles, functions to preserve ethnic traditions and family culture for subsequent generations, and currently contributes to understanding familial medical histories while validating or challenging family narratives to preserve historical, cultural, communal, and social heritage.

2.1. Vygotsky’s Theory of Knowledge Co-Creation

This research was grounded in the theory of knowledge co-creation, originating from Lev Vygotsky’s seminal work. Vygotsky’s theoretical framework on collaborative knowledge creation supports his sociocultural theory, which proposes that cognitive development is fundamentally social and collaborative in nature (

Vygotsky 1978). He contends that higher psychological functions emerge from social interactions rather than individual processes and are internalized through cultural mediation. Vygotsky emphasizes that learning manifests within social contexts, where dialogic exchange and interpersonal cooperation assume key roles in shaping individual cognition and intellectual capabilities.

A fundamental construct introduced by Vygotsky is the zone of proximal development (ZPD), which elucidates the learning potential actualized when learners interact with more capable, knowledgeable peers (

Vygotsky 1978). Moreover, Vygotsky accentuates the cultural–historical context of learning, thereby reinforcing the conceptualization of collaborative knowledge creation. He maintains that cultural tools, particularly language, function as essential mediators of social interaction and knowledge generation (

Van der Veer and IJzendoorn 1985). This theoretical perspective aligns with the understanding that learning transcends isolated cognitive processes, representing instead a dynamic interplay between individuals and their cultural environment wherein shared experiences and collaborative endeavors facilitate deeper comprehension (

Veresov and Kulikovskaya 2015).

Although Vygotsky formulated his theory well before the advent of internet technologies and digital platforms, he precisely identified and characterized social learning processes that manifest in contemporary online communities. His theoretical framework on collaborative knowledge creation, emphasizing social interaction and collaborative learning, demonstrates particular relevance to online community dynamics. His conceptualization of cognitive development as a social process underscores the significance of learner interaction, now facilitated through social media platforms. The zone of proximal development (ZPD) construct illuminates how learners achieve enhanced understanding through engagement with more knowledgeable peers in collaborative contexts. Within online learning environments, this theoretical framework manifests in collaborative task execution that promotes peer interaction and problem-solving through technological mediation (

Durrington and Du 2013).

2.2. Development of Genealogical Information Ecology

Genealogy or family history research, representing the most ancient branch of historical inquiry, originated with lineage documentation in biblical texts and persisted as a traditional pursuit across millennia, primarily through written records and physical documentation (

Davison 2009).

By the eighteenth century, genealogical research had evolved into an aristocratic pursuit, primarily due to the substantial financial resources required to fund research demanding specialized expertise (

Willever-Farr 2017). The economic and professional constraints became increasingly pronounced in the pre-digital twentieth century, as the expansion of international research necessitated physical presence in global archives, comprehensive understanding of diverse archival systems, and mastery of sophisticated search methodologies. The substantial financial burden associated with archive visitation and professional consultation continued to restrict access to this field (

Willever-Farr 2017).

Public engagement with genealogical research intensified significantly during the 1970s, though throughout approximately the next twenty-five years, genealogists remained dependent upon physical archives, correspondence-based inquiries, and direct archival research. In the pre-internet era, knowledge co-creation relied upon traditional mechanisms such as interpersonal encounters, academic conferences, and institutional collaborations (

Wenger 1999). However, this paradigm encountered substantial limitations: geographical boundaries and physical constraints impeded information access and collaborative opportunities. Traditional knowledge dissemination operated within hierarchical frameworks, restricting interactive discourse and feedback. Moreover, the dissemination process proceeded at a slower pace, relying predominantly on print publications and academic periodicals (

Wenger 1999).

Interest escalated remarkably at the millennium’s dawn with internet proliferation, transforming the field into a robust commercial sector (

Davison 2009). The 2009 emergence of platforms like Ancestry.com initiated the transition from traditional archival and library-based research to online services, despite lacking the sophisticated digital tools characteristic of contemporary practice, such as social networks and specialized mobile applications.

The digital transition has inaugurated unprecedented possibilities for genealogical research, enhancing both accessibility and efficiency. Genealogy has transformed from an elitist pursuit into a “serious leisure activity” (

Fulton 2016), motivated by diverse imperatives ranging from self-discovery to intellectual stimulation (

Moore and Rosenthal 2021).

The web transition prompted individuals to utilize software platforms and websites for family tree construction based on available data. Subsequently, genealogical communities emerged, initially communicating through chat rooms and later via email distribution networks (

Fulton 2009). Contemporary online genealogical communities differ fundamentally from their predecessors, having evolved from basic communication platforms into sophisticated research environments and becoming integral to modern genealogical research.

While basic internet searches persist, many researchers now prioritize online communities as primary information sources. These communities not only reveal previously inaccessible databases and facilitate access to visual and textual artifacts but also enable productive collaboration among “memory workers”—the amateur investigating genealogists (

Stein 2009). The lack of formal records, coupled with heightened interest in cultural heritage, drives market evolution. Genealogical service providers employ diverse investigative methodologies, including DNA genetic analysis and interviews, to accumulate substantive familial information.

These technological advancements are fundamentally restructuring methodologies for family history research and ancestral connection. Contemporary digital platforms and tools have increased the accessibility of genealogical research.

2.3. Modern Genealogical Information Ecology

The digital revolution has fundamentally transformed not only the accessibility of genealogical information but also engendered an entirely novel ecosystem of methodological tools, resources, and investigative approaches. Contemporary genealogical information ecology is characterized by an extensive array of digital resources available to researchers. Advanced technologies for information access, preservation, and enhancement of familial comprehension encompass comprehensive access to historical documentation through digital hubs and archives. These platforms facilitate the exploration of diverse records, including census data, historical periodicals, military documentation, testamentary documents, and immigration records, thereby optimizing and enriching ancestral research processes (

Pugh 2017). Supplementary resources comprise yearbooks, telephone directories, cemetery records, immigration certificates, and more.

Digital family trees have emerged as fundamental collaborative instruments, facilitating the generation, modification, and dissemination of genealogical data. Web platforms integrate sophisticated technologies such as “smart matches” that facilitate familial connection discovery and enrich family tree information (

Kaplanis et al. 2018). Certain platforms offer genealogical education, photographic enhancement, and animation technologies like “deep storytelling technologies,” enabling historical photographic subjects to narratively convey their experiences (

Family Search 2023).

Geographic information systems and cartographic technologies have substantially enhanced the capacity to comprehend familial migration patterns and analyze geographical influences on historical events. These instruments provide comprehensive contextual frameworks, enriching familial research and establishing connections between local and communal histories within individual family narratives (

Timothy and Guelke 2016).

DNA tests for genetic analysis contribute an additional dimension to genealogical research, enabling researchers to trace genetic origins, verify familial connections, and identify previously unknown relatives. These analyses facilitate the examination of migration patterns, ancestral origins, and genetic development across generations, enriching research methodologies (

Duster 2016).

Concurrently, digital collaborative platforms have revolutionized communal approaches to genealogical research. These communities facilitate the exchange of insights, methodological tools, and expertise, enabling the resolution of genealogical complexities and the synthesis of fragmented information (

Charpentier and Gallic 2020). Digital platforms enable the preservation of family histories, photographic materials, and community documentation while ensuring intergenerational accessibility. Thus, digital preservation establishes research continuity and unprecedented information accessibility (

Liew et al. 2022).

The market for genealogical products and services was projected to reach USD 4.66 billion in 2024 and USD 10.10 billion by 2031 (

Verified Market Research 2022), demonstrating a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.19% during the 2024–2031 forecast period.

As of August 2023,

SimilarWeb (

2023) analytics indicate Ancestry.com as the preeminent genealogy platform, with average visit durations of 14 min and 26 page views. Familysearch.org demonstrates average engagements of 15 min and 24 page views per visit, while MyHeritage.com records averages of 6 min and 10 pages per visit. According to

Edwards (

2022), Ancestry maintains over 3 million subscribers, 20 million DNA samples, and 20 billion records; MyHeritage, accessible in 42 languages, serves 96 million users, manages 16.1 billion records, 49 million family trees, and 8.3 million DNA analyses; and Geni encompasses 250 million profiles from 15 million users.

These metrics indicate the field’s evolution from a specialized pursuit to a robust market and widespread engagement phenomenon, attracting millions of practitioners and generating substantial revenue. Beyond commercial considerations, it maintains its attractiveness, relevance, and significance for individuals pursuing familial historical documentation.

This research expands the comprehension of contemporary genealogical information ecology by identifying and defining two emergent constituents—online communities and their managers—that collectively establish a significant knowledge hub within the current genealogical landscape. While current research has predominantly focused on digital databases and commercial platforms, the findings indicate that online communities and their managership have become integral components of genealogical information ecology, providing not only information access but also frameworks for collaborative knowledge generation and enhanced understanding of historical and cultural contexts.

2.4. Social Media and Genealogy

Social networks and digital platforms have established a novel paradigm that challenges traditional knowledge hubs, such as archives and professional expertise (

Golan and Martini 2020). Alongside websites, digital databases, and electronic archives, collaborative platforms have developed to help people connect with each other and work together to solve complex genealogical challenges (

Charpentier and Gallic 2020).

Social media has emerged as a pivotal and significant instrument, superseding websites and databases that have rapidly become conventional and antiquated. Contemporary online communities constitute essential spaces for information retrieval and dissemination across diverse domains (

Lewis et al. 2018). Their significance derives from multiple factors: they aggregate members with heterogeneous backgrounds and experiences, enriching the collective knowledge hub, providing enhanced information accessibility unrestricted by temporal or spatial constraints, and ensuring information immediacy and relevance. In the context of online communities, by 2021, Facebook alone hosted more than 16,700 genealogy-focused groups (

Vita Brevis 2023).

Within the complex genealogical ecosystem, online community managers assume an essential role in bridging the divide between digital information and users, contributing substantively to the development of communities as significant knowledge hubs. The prevailing perspective is that social media functions as an arena of egalitarian interactions generating collective knowledge. However, reality presents greater complexity. Research demonstrates that the majority of online community members are “lurkers,” engaging passively, while a limited cohort—led by community managers—constitutes the primary content generators (

Lev-On 2017). Consequently, online communities must be conceptualized as environments based on interactions between members and managers and on the collaborative knowledge generated through such interaction, rather than merely platforms for user-generated content. The managers’ roles as knowledge hubs and gatekeepers are fundamental to community dynamics (

Lev-On 2017).

Panteli (

2016) identified key managership paradigms related to knowledge sharing, particularly emphasizing knowledge transfer and facilitation of discussions. Beyond technical administration, the managers’ role encompasses value addition through information and knowledge dissemination. Managers function as central nodes for discussion initiation, query resolution, and information source direction. Research across various domains demonstrates that online community managers evolve into central knowledge hubs (

Lev-On 2017).

They facilitate connections among members with shared interests and assist in refining information requirements through mediative expertise (

Lueg 2007).

Managers significantly influence community social structure and knowledge dissemination patterns, potentially creating “distortions” in typical interaction paradigms that may deviate from characteristic social network “power law” distributions (

Cottica et al. 2017). They encourage enhanced participation from less active users, thereby transforming network dynamics and amplifying knowledge flow.

As central hubs in online community dynamics, managers serve as critical knowledge and information intersections. They guide community discourse and establish content parameters, thereby maintaining information quality and relevance (

Amann and Rubinelli 2017). In their gatekeeper capacity, they monitor information quality to ensure adherence to community standards.

The centrality of managers in social media communities encompasses content production, initiative, discussion contribution, and information provision. They function as knowledge and information hubs: soliciting and providing information hubs (

Lev-On 2024a), contributing (

Agarwal and Toshniwal 2020), creating and sharing (

Gal et al. 2023), and managing knowledge (

Huffaker 2010), and promoting motivation and knowledge transmission (

Mustapha 2018). As knowledge experts, they respond to and encourage engagement (

Lee et al. 2019), reflecting prosocial orientation (

Jadin et al. 2013). They establish and maintain knowledge managership status through digital platforms (

Golan and Martini 2020).

The central role of community managers in knowledge production and management reflects a broader shift in authority structures within social networks. Social networks demonstrate a transition from traditional hierarchical authority to more distributed authority based on social media presence and activity (

Golan and Martini 2020).

Based on these changes in knowledge sharing patterns, this study examined how online genealogical communities and their managers function as knowledge hubs within the broader genealogical information ecology. The research examined how these communities, under the guidance of their managers, serve as spaces where genealogical knowledge is created, shared, and refined through member interactions. This suggests that these online communities have evolved into essential hubs (

Lev-On 2024a) in the genealogical information landscape, where both practical research expertise and theoretical genealogical knowledge converge and develop through the facilitation of community managers.

Just as Instagram enables direct connection between managers and their followers, evident when politicians share personal updates and daily life videos while bypassing traditional media, online communities similarly facilitate direct contact between information seekers and community managers without traditional institutional mediation (

Golan and Martini 2020). Community managers promote connections between members with shared interests and help users understand and refine their information needs.

Given their role, community managers employ various tools and strategies to enhance their knowledge dissemination effectiveness. The use of technological tools for data management, online communication, and content creation enables more efficient information flow management (

Tohani et al. 2023). Additionally, they develop strategies to improve information quality and combat misinformation (

Rohman 2020).

This research explores the role of genealogy community managers in social media as central knowledge hubs for preserving and making accessible family and community history. Despite social media’s growing importance in family history research, there has not been any comprehensive study examining how community managers function as knowledge hubs: leading the processes of collecting, documenting, and preserving genealogical knowledge, while helping community members reconstruct their family narratives and the social fabric of their historical communities.

Online communities typically feature several knowledge experts who serve as knowledge hubs. It is neither self-evident nor necessary that community managers become the central knowledge hubs beyond their organizational and administrative duties (

Lev-On 2024b). Establishing the community or holding a formal management role does not automatically grant content expertise status: such expertise is built through significant contributions to discourse and the shared knowledge base. This phenomenon is particularly prominent in genealogy communities, where community managers typically serve as knowledge hubs.

Fulton (

2009) studied online genealogy community managers and identified their significant influence, describing them as “super-participants” or “information champions.” According to her research, these dedicated individuals are central contributors to the genealogical community. Their involvement typically begins with a defining event, leads to thorough data collection, continues with searching for breakthroughs and constructing complex family trees, and culminates in publishing and preserving the collected information.

However, it is crucial to note that

Fulton’s (

2009) study reflects a vastly different technological landscape from today’s reality. The research was based on then-available technology, primarily email distribution lists. Study participants had to rely on limited, primitive digital databases that were hardly user-friendly and cumbersome software for building family trees.

Currently, genealogical information ecology has evolved significantly, thanks to the integration of advanced technologies and new skills. The substantial change in dynamics since

Fulton’s (

2009) study over a decade and a half ago emphasizes the need for updated research on the role, practices, and impact of genealogical community managers in the social media age.

Several methodological and conceptual limitations are discussed in detail later in the paper. These limitations are central to understanding the scope and implications of the study and are revisited critically in the concluding sections.

This article is the second in a series of three chapters comprising a doctoral dissertation on digital genealogical knowledge practices. The first chapter examined collaborative inquiry within a WhatsApp group, while the current study focuses on managerial roles in Facebook-based communities. Although this article stands independently, certain themes and limitations are elaborated upon more fully across the broader project and are revisited critically in the concluding sections.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Population

The study participants were managers of diverse online genealogical communities, overseeing Facebook groups that engage thousands of members. While some approach genealogy as a hobby, these managers undertake self-directed professional development and possess significant expertise in the field. The study encompassed fifteen managers from Jewish communities spanning global locations, including Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Morocco, South Africa, Australia, Poland, Germany, Romania, Slovakia, the former Soviet Union, Rhodes, India, Argentina, and the United States. These communities represent both extinct historical communities now administered by descendants and active contemporary ones, either in their original locations or new settings.

While most of the groups studied operate primarily in English, several also use Hebrew, French, or other languages relevant to their communities. Communication with group managers was conducted in English and Hebrew depending on the participants’ preferences and linguistic backgrounds. All interviewees demonstrated fluency in at least one of these languages, allowing for clear and effective dialogue throughout the research process.

The research focused on understanding community managers’ perceptions of their role and their communities’ function as knowledge hubs, as they occupy a unique position at the intersection of community administration and knowledge management. Selected communities met well-defined inclusion criteria designed to ensure relevance, diversity, and sustained engagement. These criteria encompassed group size, activity level, type of community, geographic representation, and the expertise of the group managers. A summary of these criteria is presented in

Table 1.

The participant demographics showed a two-thirds male majority, with most managers being over 60 years old and the remainder between 36 and 50 years of age.

4.2. Data Collection

The research instrument evolved through systematic development, initiating with a review of questionnaires from previous studies examining community manager characteristics, attributes, and motivations in social media contexts (

Lev-On 2024a;

Eitan and Gazit 2023). Subsequently, questions were adapted for the target population of online genealogical community managers. Following preliminary exploratory interviews and six comprehensive interviews, emergent patterns informed questionnaire refinement.

Data collection proceeded through in-depth interviews averaging approximately one hour in duration. Some interviews were conducted in person, while those around the world were carried out via Zoom meetings. Both were digitally recorded. Methodological rigor was maintained through consistent redirection to research questions when responses diverged, ensuring focused data collection while preserving rich informational depth.

All interviews underwent digital recording and software-assisted transcription. After identifying relevant communities, managers were recruited through snowball sampling and contacted via Facebook Messenger with standardized research participation invitations. When direct messaging attempts were unsuccessful, recruitment was expanded through public posts in the relevant communities.

4.3. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis followed systematic, structured protocols. Initial familiarization with material proceeded through iterative transcript review and preliminary notation. Initial coding identified meaningful textual units with appropriate code designation. The third phase involved preliminary code aggregation into potential themes, followed by relationship examination between themes and the comprehensive dataset. The fifth phase encompassed theme essence refinement and precise definition, culminating in representative quote selection and the presentation of coherent findings.

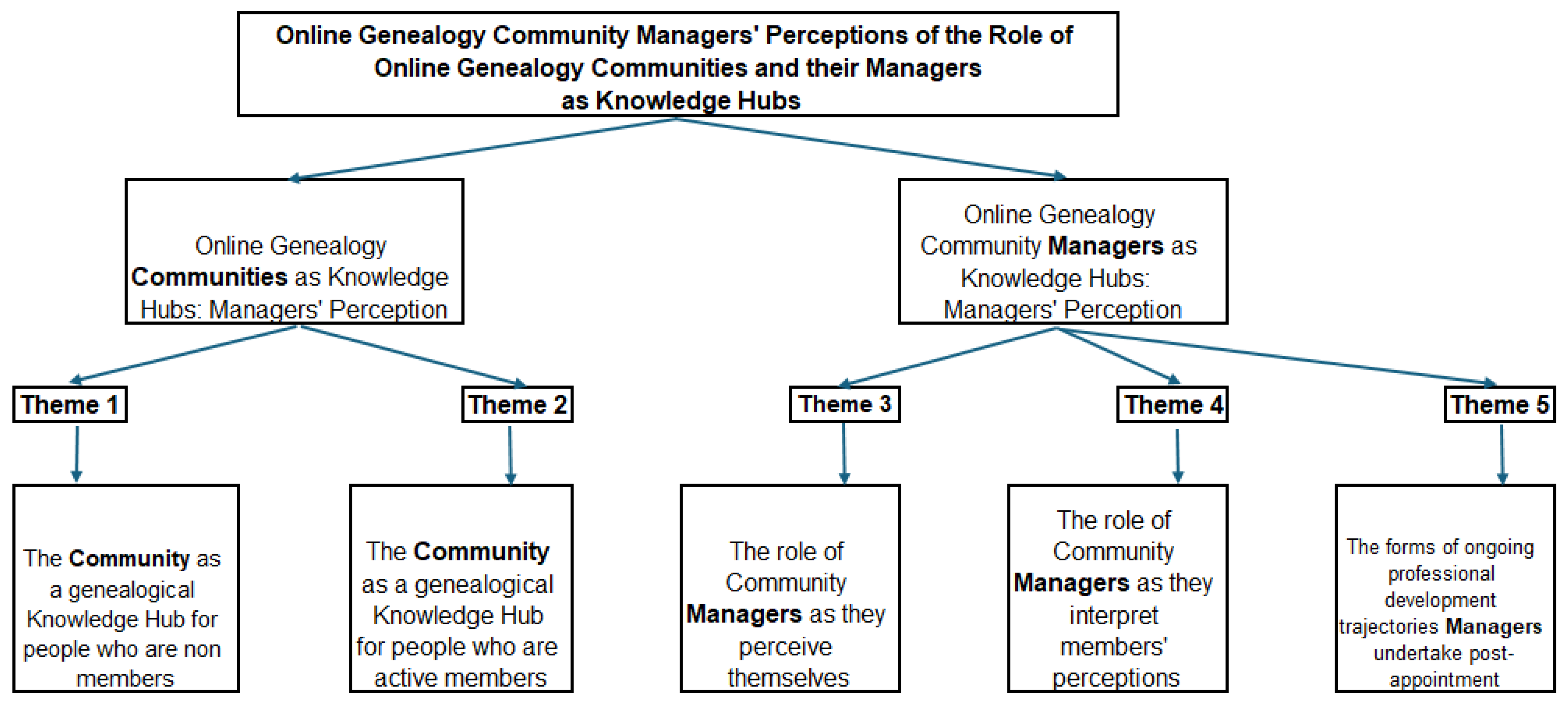

Throughout analysis, responses to each inquiry were aggregated to identify recurring patterns, with attention to emergent topics from initial interviews, including follow-up with original participants for comprehensive understanding. Analysis reliability was ensured through independent coding cross-validation between two researchers, with collaborative discussion to achieve consensus on central themes. Thematic analysis revealed five central themes: two addressing online community knowledge hub functions for members and non-members, and three examining manager self-perceptions of their role, community perception as they interpret it, and knowledge hub strategies they pursue.

4.4. Ethics

The research, receiving university ethics committee approval, incorporated comprehensive ethical considerations. All participants received detailed research objective explanations and provided signed or Zoom-recorded informed consent. Privacy protection involved numerical and alphabetical substitution for participant and community identifiers respectively, with explicit withdrawal rights communication. Research materials were secured with restricted researcher access.

4.5. Scope and Limitations of Data Accuracy

It is important to note that this study focused on managers’ perceptions of knowledge quality and authority. The factual accuracy of genealogical claims was not independently verified. However, as researchers with expertise in the field, we observed that many managers demonstrated rigorous information practices: they cross-referenced data, consulted reliable sources, and engaged with authoritative genealogical platforms. Moreover, they did not hesitate to acknowledge gaps in their knowledge when necessary, reflecting a conscientious and transparent approach to genealogical inquiry.

5. Findings

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the analysis of interviews revealed five predominant themes. The themes emerged from analysis of managers’ interviews and solely reflect their own subjective perceptions and understanding of their role and the community’s function as knowledge hubs. The initial two themes examine the community’s function as a knowledge hub according to managers’ perceptions, addressing both non-member and active participant engagement. The subsequent three themes explore the community managers’ role, analyzing their interpretation of how they perceive their positioning within the genealogical information ecology, how community members view their role, and the forms of ongoing professional development trajectories managers undertake post-appointment, to reinforce their position as knowledge hubs.

The following analysis presents the managers’ perspectives and perceptions of their communities’ and their own roles as knowledge hubs. It is important to note that these findings reflect the subjective viewpoints of the managers interviewed, while other stakeholders may perceive these aspects differently.

5.1. Theme 1: Online Genealogy Communities as Knowledge Hubs for Non-Members—Managers’ Perspective

Interview analysis reveals distinct pathways in genealogical information acquisition, with information seekers typically utilizing several primary channels. As Interviewee 8 articulates, “Most individuals initially seek familial sources of information, frequently an elder with preserved memories… Subsequently, they pursue institutional databases such as the Diaspora Museum.”

Following exhaustion of primary familial sources, digital search engines, particularly Google, become the predominant channel. This pattern is exemplified by Interviewee 3: “Information seekers predominantly arrive through Google searches. Those investigating Jewish community information invariably discover my platform.”

However, while search engines function as initial access points, over half of participants emphasize online communities’ distinctive value proposition. As Interviewee 12 elucidates: “Contemporary information seekers gravitate toward communities due to their interconnected nature. While websites facilitate specific terminological searches, they cannot provide contextual frameworks, narrative associations, or familial connections. Communities provide comprehensive contextual understanding.”

Moreover, online communities’ efficacy manifests in their emergence as primary information acquisition channels. Approximately 40% of participants emphasize this transformation, with Interviewee 13 noting, “Within our ethnic demographic, our Facebook community has become the preliminary resource for information seekers.”

5.2. Theme 2: Online Genealogy Communities as Knowledge Hubs for Active Members—Managers’ Perspective

While the previous theme examined information seeker access patterns, this theme investigated the community’s function as a primary knowledge source for active participants. All managers reported that post-membership, the community becomes members’ principal information resource, with the online platform facilitating memory, visual, and narrative sharing while demonstrating superior efficiency compared to traditional newsletters.

Two managers provided particularly illuminating perspectives on the community’s role as a knowledge hub. Interviewee 5 offers a comprehensive view of the community’s practical functionality, emphasizing the breadth of services available: “Community participants engage through inquiries, seek document interpretation assistance, and utilize digital hubs and historical archives recommended within the group, trusting in the community’s capacity to provide authoritative and definitive information.” This perspective highlights the community’s operational excellence and the trust members place in its expertise across multiple research domains.

In contrast, Interviewee 11 provides a profound historical and emotional dimension to the community’s significance, focusing on its transformative power for genealogical reconstruction: “Our platform facilitates the reconnection of long-severed familial connections. In our historical community of 2000–3000 Jewish residents over four centuries, universal interconnection existed. The online platform enables the restoration of these historical connections.” This manager’s perspective reveals how online genealogy communities transcend mere information sharing to become instruments of cultural preservation and familial healing, restoring connections that span centuries of displacement and historical disruption.

Together, these perspectives demonstrate that online genealogy communities function simultaneously as practical research tools and as bridges to ancestral heritage, serving both immediate informational needs and deeper quests for identity and belonging.

5.3. Theme 3: Genealogy Online Community Managers as Knowledge Hubs—Managers’ Self-Perception

Following examination of the community’s function as a knowledge hub, analysis focused on managers’ role in conceptualization, particularly self-perception and functional interpretation. The findings revealed diverse self-conceptualizations ranging from comprehensive expertise claims to pronounced humility.

Approximately 50% of participants present themselves as knowledge hubs. Interviewee 2 self-identifies as “the authoritative source” and “preeminent global expert” regarding their community’s Jewish population. This position is echoed by Interviewee 9: “Individual consultation requests reflect recognition of comprehensive and precise response capability. Extensive field experience engenders member trust.”

A significant emergent theme encompasses responsibility for communal heritage preservation. Interviewee 8 emphasizes interaction management importance: “Facilitating interactions demands substantial responsibility, ensuring universal recognition and narrative acknowledgment.” Furthermore, Interviewee 10 articulates clear strategic vision: “The objective is establishing the world’s predominant information hub for regional Jewish communities. While current positioning appears optimal, the challenge involves meaningful material utilization.”

5.4. Theme 4: Genealogy Online Community Managers as Knowledge Hubs—Managers’ Interpretation of Community Members’ Perceptions

After examining how managers conceptualize their own role, this section analyzes how they believe community members perceive them. These findings derive exclusively from managers’ self-reported perceptions of how community members view them, as direct examination of member attitudes exceeded study parameters.

Interview analysis indicated universal manager perception of significant community standing. Interviewee 9 states: “Members anticipate contributions and discussion participation. Substantial investment in ancestral documentation generates universal appreciation for voluntary contribution.” Similarly, Interviewee 6 describes member attitudes: “Members regard me as authoritative source, anticipating publications, responding enthusiastically to content, and regularly seeking specific consultation.”

Manager status manifestation extends beyond content anticipation to professional authority recognition, as Interviewee 11 notes: “I am acknowledged as the community’s authoritative source. Members frequently express, ‘Your contributions have illuminated previously undocumented aspects.’ Recognition and commendation are frequent.”

Approximately 80% of managers interviewed reported on the substantial responsibility accompanying their position. Interviewee 8 emphasizes: “Heritage preservation responsibility resides with the community rather than institutional bodies.” Community narrative preservation represents an internal obligation.

Some managers presented nuanced role interpretations, exemplified by Interviewee 10: “My function transcends managership to encompass guidance. Member consultation carries the significant responsibility of facilitating access to factual information and technological resources.”

The managers’ status is reflected not only in content expectations but also in recognition of their professional authority, as Interviewee 11 attests: “I’m considered the ultimate authority on my community. Community members note that ‘it’s all thanks to you! Nobody knew, nothing was written, and we finally see.’ I receive abundant appreciation and praise.”

Alongside status recognition, approximately 80% of managers emphasized the heavy sense of responsibility accompanying their role. For instance, Interviewee 8 emphasizes: “The responsibility for preserving heritage lies with us, and we cannot expect a country or institutions to do it for us. It’s each community’s duty to preserve its own story.”

Finally, some managers presented a more balanced approach to their role, as reflected in Interviewee 10’s words: “I see myself not just as a manager, but as someone who guides the way. When group members approach me, I feel it’s a great responsibility to be the factor that leads them to truth and technology.”

5.5. Theme 5: Forms of Ongoing Professional Development Managers Pursue After Taking on Their Role

Following examination of managers’ self-perceptions and how the community perceives them, this theme focused on translating these perceptions into practical actions. Analysis of the interviews revealed that all managers, before but increasingly after assuming community manager roles, invested considerable efforts with varying levels of commitment in deepening their knowledge and capabilities across six main domains.

First, in the domain of self-learning and research, approximately 90% of managers emphasize the importance of continuous learning. As Interviewee 14 describes: “I am autodidactic. I read extensively and rarely need a formal educational framework to develop expertise in a specific subject.” Similarly, Interviewee 3 notes: “I acquired all my genealogical knowledge through self-learning, through intensive research and connections with key community members.”

This commitment to research and learning is also reflected in significant resource investment, as Interviewee 2 describes: “I made 20–30 trips to my community’s country, invested millions in documentation and research… I conducted comprehensive research in archives and the national library.” Interviewee 6 adds: “I frequently read and search for information online… I’m interested in personal and family stories, researching in digital archives.”

Second, in the domain of documentation and preservation, approximately 90% of managers conduct extensive activities. Interviewee 3 describes: “I photographed all the tombstones in Jewish cemeteries in my community’s geographical location… I interview people and document their stories… I collected historical books and materials.” Similar investment is described by Interviewee 7: “Through JewishGen, we found ourselves as a group of amateur researchers and decided to try photographing all our city’s documents… For three years, we scanned and photographed all the documents.” Interviewee 8 emphasizes the importance of preservation: “The group isn’t just for finding connections. It’s meant to preserve heritage.”

In the third domain, event and activity organization, managers initiate a wide range of activities. For example, Interviewee 5 elaborates: “Our community has an annual calendar of events throughout the year. I organize social gatherings, holiday celebrations, memorial ceremonies, and I’ve also initiated and facilitated Zoom courses on genealogical research skills for community members.” This diverse activity is also reflected in Interviewee 3’s remarks: “About seven years ago, we held a major gathering attended by around 400 people… including X, a very important public figure in Israel who was born in [country]… I also organized meetings in (city) and Zoom conferences attended by about 300 people.” Interviewee 12 adds: “I initiated a physical event… with [community-specific] games and brought an interesting lecture… There was also a culinary gathering.”

In the fourth domain, collaborations and mutual learning, extensive activity occurs across all communities. Interviewee 4 describes: “I learn tremendously from senior board members who have been in the field for decades. They teach me about genealogy, and I teach them about technology.” These collaborations extend to research institutions, as Interviewee 5 describes: “We work with local historians and locals who have taken it upon themselves to assist and research Jewish topics (in the region).” Interviewee 3 adds: “I maintain contact with Center X at Y University and with the Jewish museum there.”

In the fifth domain, development of unique skills, approximately 80% of managers acquire specific skills required for their communities. Interviewee 14 provides translation services: “Some have their parents’ ID cards in (language). They ask me to translate the dates for them, as (country) has its own calendar.” Interviewee 5 describes acquired technological skills: “I taught myself to develop interactive maps, upload scanned books to shared drives, perform digitization.” Interviewee 1 adds: “I studied areas like museology and curation.”

Finally, in the domain of long-term commitment, sustained investment in knowledge deepening is evident in at least 80% of managers. As Interviewee 14 describes: “For the past five years, I’ve invested all my energy and time in studying and researching the history and culture (of the country). I’ve already written five books on these subjects.” This commitment is also reflected in managers’ impressive tenure, as evidenced by Interviewee 3: “I’ve been involved in documentation for 25 years, including creating a website and Facebook group to preserve heritage,” and Interviewee 9, who dedicated “over 40 years to documenting the stories of my community members.”

It is important to note that these domains do not operate in isolation, but maintain complex interrelationships, reinforcing the managers’ role as knowledge hubs and gatekeepers of community heritage.

6. Discussion

This research examined the roles of online communities and their managers as knowledge hubs in the genealogical ecosystem based on the managers’ own perspectives. While millions of people engage in family history research through online communities, little is known about how these communities and their managers function as knowledge hubs in the genealogical knowledge landscape, particularly from the managers’ point of view. The study aimed to clarify the position of these communities in the broader knowledge ecology of genealogy and to examine the managers’ contributions, drawing on relevant insights from studies of community management in other fields.

Through interviews with fifteen Facebook genealogy community managers, the study revealed five key themes describing how managers understand these knowledge hub functions. The first two themes focus on how communities serve as knowledge hubs for both non-members and active participants, while the remaining three explore managers’ perceptions of their own role as knowledge hubs, including their self-perception, their interpretation of community members’ views, and the forms of continued professional development they pursue to deepen their expertise.

While the findings offer valuable insights into the managers’ perspectives, it is important to examine their role within a broader analytical framework. Managers often portray themselves as community-oriented, emphasizing openness, support, and collaboration. However, their responsibilities—such as moderating discussions, validating genealogical claims, and selecting which sources to highlight—also position them as influential actors in shaping the flow of information, maintaining group norms, and determining which voices gain visibility. This combination of supportive and decision-making responsibilities shows that managers hold a certain level of influence alongside their commitment to openness. It encourages further consideration of how decisions are made and how knowledge is shared and managed within these communities.

Insights from the interviews indicate that online communities are increasingly viewed as central knowledge hubs in contemporary genealogy, reflecting a notable move away from traditional research practices. While historical genealogical methodology relied upon physical archives, academic conferences, and interpersonal encounters, managers report a transition toward digital, decentralized, and globalized information ecology. This transformation aligns with

Willever-Farr’s (

2017) research, which identified digital communities’ democratizing influence and enhanced accessibility. The managers’ accounts suggest that this digital ecological transition not only expanded participant demographics but generated novel collaborative dynamics, facilitating information contribution, insight sharing, and reciprocal learning.

From the managers’ perspective, their role as community leaders has evolved to represent emergent “knowledge authorities” within digital genealogy. They describe integrating technological expertise, comprehensive historical knowledge, and social mediation skills in their work. Their reported responsibilities transcend technical administration to encompass member connection facilitation, collaborative engagement promotion, and integration of traditional knowledge with contemporary digital methodologies. These dynamics, emphasized in

Charpentier and Gallic’s (

2020) research, illustrate the complexities inherent in digital community administration, particularly within specialized domains like genealogy.

The managers’ descriptions of knowledge sharing and learning within their communities highlight the continued relevance of

Vygotsky’s (

1978) theory of collaborative learning. Although developed before the rise of social networks, the current findings support his view that social interaction plays a central role in learning and the co-construction of knowledge. These communities often reflect the concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD), where interactions with more experienced managers and peers help members deepen their understanding and advance their genealogical research. However, the findings suggest a more nuanced dynamic: community managers do not merely scaffold learning, but also curate, moderate, and sometimes constrain the flow of genealogical information. This dual role complicates the notion of the ZPD, indicating that in digital spaces, learning is shaped not only by peer interaction but also by hierarchical mediation and epistemic gatekeeping.

This observation invites a reconsideration of Vygotsky’s framework, suggesting that while it remains relevant, it should be adapted to account for the structured authority exercised by community managers. Their dual role as facilitators and gatekeepers introduces hierarchical dynamics that influence not only what is learned but also whose voices are amplified and legitimized within the community. These dynamics raise broader questions about power, access, and epistemic inclusion in digital learning environments, and highlight the need to critically examine the mechanisms through which genealogical knowledge is constructed and validated online.

These findings reinforce and extend

Stein’s (

2009) conceptualization of online communities as central genealogical information hubs. Managers describe how their communities facilitate access to previously obscured databases and contribute significantly to collective memory formation. Although Stein’s research predates current technological developments by fifteen years, the managers’ accounts suggest that her fundamental assertion regarding online communities’ centrality remains valid, with subsequent technological and social developments enhancing their position as knowledge hubs.

Of particular significance is managers’ perception of their role as custodians of communal memory, especially within communities focused on Holocaust-affected, migrated, or diminished populations. The managers describe how their activities expand community function beyond knowledge dissemination platforms to spaces that preserve and transmit collective memory, adding new dimensions to the traditional understanding of genealogical research communities.

Finally, the findings highlight what managers perceive as their exceptional commitment levels. While

Fulton (

2016) characterized genealogy as “serious leisure,” the interviewed managers describe their roles as having evolved beyond recreational boundaries into intensive endeavors demanding substantial temporal, energetic, and resource investment. According to their accounts, this commitment encompasses content management, interaction facilitation, collaboration strategy development, technological adaptation, continuous learning, and support for individual and collective member requirements.

7. Conclusions

Based on community managers’ accounts and perceptions, this research presents a distinctive contribution to understanding genealogical information ecology within the digital paradigm. Its primary innovation lies in identifying two emergent constituents: online communities as collaborative knowledge hubs and community managers as central knowledge authorities in the generation, formation, and governance of collective knowledge according to managers’ self-perception.

The research emphasizes the fundamental transformation in genealogical knowledge creation and dissemination processes, evolving from traditional methodological constraints to contemporary digital communities’ virtually unrestricted accessibility.

While previous studies, such as

Charpentier and Gallic (

2020), focused on platform characteristics, the current research deepens understanding of online genealogy communities’ internal dynamics and administrative significance. These insights complement

Stein’s (

2009) and

Willever-Farr’s (

2017) work while expanding theoretical frameworks by positioning manager roles as pivotal knowledge hubs within digital information ecology.

7.1. Limitations of the Study

Despite its contribution to understanding the central role of online genealogy communities and their managers as knowledge hubs, the current research has several methodological limitations. The first limitation lies in its reliance on community managers’ own perceptions, who are themselves integral parts of the knowledge ecology they describe. As they discuss their own role and position within this ecology, there may be inherent bias in their portrayal of their place and function. The managers might have emphasized or elevated their position while potentially understating other factors. Future research should examine the perspectives of community users themselves and those interested in genealogy, but not participating in these communities to provide a more comprehensive understanding of these knowledge hubs.

Another limitation concerns the focus on Jewish online genealogy community managers, which may reflect unique dynamics related to ethnic origin and Jewish history that may not necessarily represent general genealogical communities.

Additionally, while the focus on Facebook as a platform may appear to be a methodological limitation, findings from this dissertation’s first chapter, which examined collaborative genealogical activity in a WhatsApp group, indicate similar patterns of community knowledge co-creation across other social media platforms.

7.2. Challenges and Future Research

This study offers both practical and theoretical contributions, highlighting the role of digital communities in expanding access to genealogical information while shedding light on the administrative complexities these communities face. The findings open new avenues for research, including inquiries into how members perceive administrative roles and contribute to the collective production of genealogical knowledge. Further investigation is also warranted into inter-community dynamics and patterns of knowledge exchange.

One pressing challenge concerns the continuity of knowledge and its intergenerational transfer among community managers. As many current genealogy group administrators are of advanced age, questions emerge about how their accumulated expertise will be preserved and passed on to future leaders. This issue is especially relevant in light of growing technological demands and the need to combine genealogical proficiency with digital literacy.

Future research might also explore DNA-based genealogical communities, such as networks formed by individuals discovering shared paternity through sperm donation, and Y-DNA surname groups commonly found on platforms like FTDNA. These communities are often shaped by self-appointed leaders who take on genealogical roles and responsibilities. Unlike traditional genealogists, who often work to reconstruct historical narratives of entire communities, these leaders tend to focus on personal or familial connections, fostering new forms of identity and belonging. While many demonstrate sincere dedication and play a constructive role in shaping these communities, it is worth noting that the quality and accuracy of the knowledge produced—and the basis of certain claims to authority—may vary, and merit further critical attention. Exploring these dynamics can offer valuable insights into the evolving nature of leadership and community within genetic genealogy.