1. Introduction and Background

The confiscation of organized crime assets is an act that has a strong social impact, contributing not only to defeating illegal organizations, but also to strengthening legality and generating benefits for the community. The confiscation of assets from organized crime groups is a particularly significant phenomenon in Italy, but it is becoming an increasingly prevalent problem at a European (e.g., Directive (EU) 2024/1260 of the European Parliament and of the Council “On assets recovery and confiscation; European research Program “RESTART: A new paradigm to protect the EU core values and strengthen democratic participation through the public and social reuse of assets”) and a global level.

Investigating the problem in Italy, where the phenomenon is particularly significant, is also of great interest to other geographical contexts that may encounter the same issues. This study focuses on the Italian context in particular, on the Lombardy region, where there is a strong concentration of these assets (

Maestri 2016) due to its historic alignment with migration patterns from the southern regions of the country, where organized crime has developed, and along with the economic opportunities system that is closely intertwined with migration (

Dalla Chiesa 2016). The choice of the Lombardy region as study area is also linked to the regional administration’s demonstrated interest in addressing the issue, as shown through the activation of co-financing measures for municipalities, which are proposed annually to encourage interventions. This political will of the region has allowed research to be developed in a context marked by the presence of stakeholders who are already sensitive to the issue and willing to participate in experimentation.

The literature on confiscated assets has focused mainly on the legislative framework (

De Benedictis 2019;

Cisterna 2012) and the social impact of reusing assets (

De Benedictis 2021;

Dalla Chiesa 2016;

David and Ofria 2014), but has not dealt in depth with the aspects of management and governance once municipalities assume responsibility for these assets. In fact, with limited exceptions (

Ferroni 2022;

Ferroni 2023), there is no clear framework in the literature regarding the critical issues surrounding the current obstacles to the reuse of confiscated assets. Moreover, the literature also lacks a definition of innovative approaches aimed at overcoming process obstacles and generating social benefits. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to fill the gaps in knowledge on the barriers and drivers across the management and reuse process of confiscated built assets, and to define a win–win innovative and replicable model capable of promoting the confiscated building reuse process and social benefits for various stakeholders and vulnerable people, combining building requalification and training through the activation of a “construction site school”.

Construction site schools can be conceptualized as part of active labor market policies (ALMPs), as training plays an important role within ALMPs. Contemporary welfare states have been drifting toward an activation approach since the 1980s. Within social investment approaches, much emphasis is placed on equipping jobseekers with skills that would enable them to navigate current labor markets. However, Italy has traditionally been a country with low ALMP expenditure compared to other European countries (

Meager 2009). This makes the development of innovative initiatives more crucial.

After providing a review of the legislative framework, the social impacts of the management and reuse of confiscated assets, the current issues that arise throughout the process, and the role of active labor policies (as construction site schools are positioned within this policy framework) in activating fragile groups, such as NEETs (people not in employment, education, or training)—and, by doing so promoting social inclusion through training and employment—this section identifies research gaps and outlines the research goals and results presented in this paper.

Section 2 presents the data and methodology used to analyze the critical issues and needs of confiscated built assets, and to define a win–win strategy for the innovative model and the activation of construction site schools.

Section 3 shows the results: first, it provides an overview of the situation regarding confiscated assets in the Lombardy region, summarizing their physical characteristics and identifying the key drivers and barriers to their reuse; second, it shows the results of the win–win multi-stakeholder network applied in a pilot project.

Then,

Section 4 discusses the social benefits of the reuse of confiscated buildings, considering not only the social aim of the use phase but also the social aim of the construction phase, enabled by the activation of construction site schools that provide professional and educational qualifications to vulnerable people and students.

Finally, the Conclusion traces the necessary improvement actions for model replicability and the relatively important strategies for forecasting future projects.

1.1. Italian Legislative Framework on Confiscated Built Assets

The phenomenon of built assets confiscated from organized crime groups in Italy is based on a structured legislative framework, developed in the last 45 years, which covers seizure, confiscation and reuse for social purposes.

Law 646/1982, called the “Rognoni-La Torre law”, provided a decisive boost to Italian legislation against organized crime. This law introduced, for the first time, the legal authority in Italy to seize and confiscate assets belonging to criminal organizations. The goal of this law is to fight organized crime by weakening it economically and depriving it of its assets.

In the 1990s, the legislation was further strengthened by Law 109/1996, which streamlined the procedure through determining that such confiscated property should be used for institutional and social purposes. This new approach aimed to return the illegally misappropriated common goods to the community, promoting the social and economic development of the territories most affected by criminal presence (

Falcone et al. 2016;

Mira and Turrisi 2019).

In 2007, the “Budget Law” established that the government must own confiscated built assets for public uses related to institutional activities of public administrations, public universities, public bodies, and public cultural institutions. Currently, in fact, confiscated built assets are assigned to local public entities or to the third sector through local authorities. The confiscated built assets may be transferred from the central government to the property of the municipality, province, or region in which the built asset is located (

Pezzullo 2022). Voluntary associations and organizations, social cooperatives, social rehabilitation and treatment centers, and environmental associations, etc., may directly administer the property or grant it free of charge to communities. By reusing these assets, both the buildings and the social services can be returned to the community (

Fraschini and Putaturo 2014).

The “New Anti-Mafia Code”, Legislative Decree 159/2011, boosts measures aimed at ensuring the transparency and effectiveness of the judicial administration of assets by enhancing the role of the National Agency for Seized and Confiscated Assets (ANBSC).

At the regional level, there are also legislative initiatives to enhance the requalification and reuse of confiscated assets. For example, the Lombardy region, through Regional Law 17/2015, established a financing fund for the recovery and reuse of confiscated property in its territory, accessible through a public tender (

Polis 2016). Lombardy municipalities may obtain funding of up to 50% of the total cost of the renovation. In addition, there are also non-legislative initiatives planned by regions aimed at raising awareness of opportunities for the reuse of confiscated properties, as is the case in Lombardy, through the organization of training courses (webinars, workshops and training courses) aimed at municipalities and third-sector organizations.

1.2. Social Impact of the Return of Confiscated Assets to the Community

The return of confiscated assets to the community is gaining increasing interest among Italian municipalities, thanks to its potential to generate several social benefits.

The requalification of confiscated properties has a strong and intrinsic social and symbolic value the asset belongs to the community. Confiscated assets represent tangible economic value and can help local communities grow economically and socially, becoming services and catalysts for positive development (

David and Ofria 2014).

The support of entities (e.g., the third sector) involved in the reuse of confiscated assets is essential, as this represents the most effective policy option in the fight against organized crime and the economic and social development of the territory (

David and Ofria 2014). Third-sector entities and citizen groups are generally involved in the social reuse of assets in an informal manner, as the procedure leading to the final confiscation of assets can take many years (

Ferroni 2022).

Considering the best cases of reuse and valorization of confiscated built assets, it is possible to list some examples that allow for the activation of social services aimed at citizens and local communities, in terms of

spaces for children, young people, and the elderly, creating additional spaces for education, culture, sports, etc.;

services for the social inclusion of people experiencing conditions of exclusion and marginality in the municipal territory (family homes, homes for people who are victims of violence, homes for the elderly, etc.);

opening of new employment opportunities for young people and vulnerable people, while producing goods and services of public interest (artisanal social cooperatives, nonprofit workshops, etc.);

increasing diffuse university residences (a possibility recently introduced by the Minister of University and Research, thanks to the “National Recovery and Resilience Plan” funds).

1.3. Current Problems Throughout the Process of Reusing Confiscated Buildings

Despite the structured regulatory framework and the recognized social value of reusing confiscated assets, there are still several critical issues in the process of managing confiscated built assets.

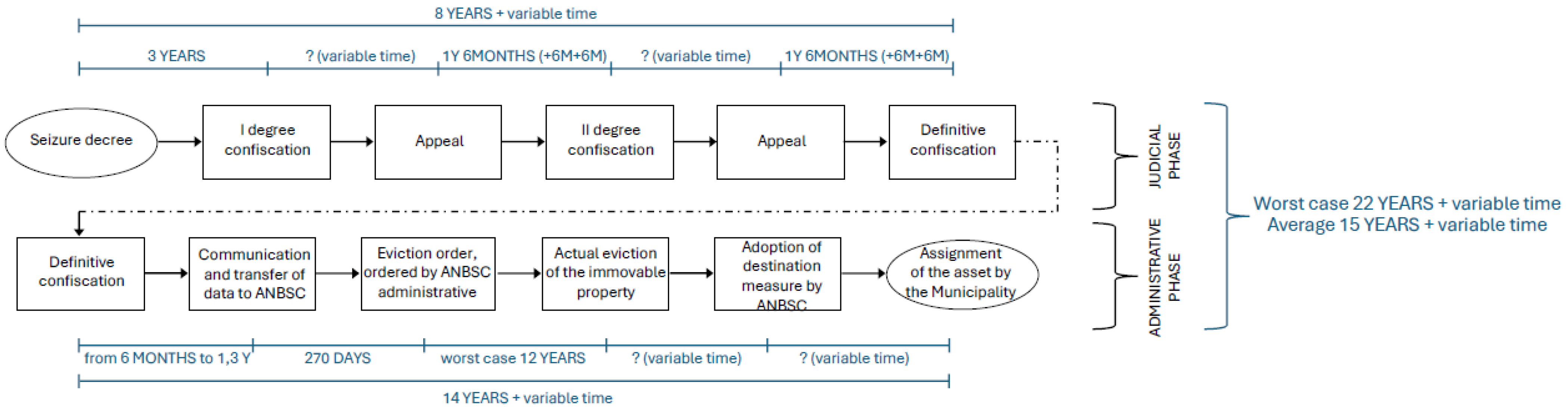

The judicial and administrative process for allocating built assets to public entities currently takes a long time (

Figure 1). On average, it takes approximately 12 years from the time of seizure to the time of reuse for social purposes (

Ferroni 2022). Therefore, properties are often transferred to municipalities in a state of disrepair, degradation, and vandalism, and are thus considered by the community as an economic burden and a territorial disvalue.

According to data updated in 2023, in Italy, the total number of assets seized and confiscated from organized crime groups was 43,422. Of these, around 19,764 still managed by the ANBSC (

ANBSC 2024), meaning that they had not yet been transferred to other entities and were not yet being reused.

The management of confiscated built assets requires the cooperation of multiple stakeholders and the coordination of many processes regarding data and information gathering concerning the judicial phase, transfer of ownership, building eviction procedures, site surveys and inspections, technical due diligence, design process for building renovation and reuse, cost assessment, searching for funding opportunities, etc.

Frequently, municipalities—particularly small onesare unable to manage this complex process due to both a lack of economic resources and a lack of management skills. However, at present, neither a clear framework for addressing the issues nor a model capable of activating a synergistic network among the various actors to overcome the managerial and economic obstacles of the process has yet been identified.

1.4. The Potential of Activation of Job Training for Vulnerable People

As already highlighted, the innovative model analyzed is based on activating a “construction site school” within confiscated properties slated to be repurposed for use by third-sector organizations. In doing so, the model effectively combines the physical redevelopment of confiscated assets with practical work-based training opportunities—an essential component of active labor market policies (ALMPs). This approach fits into the broader transformation process of European welfare systems, marked since the 1990s by an increasing emphasis on activation policies. In this respect, Co-WIN is aligned with the social investment (SI) strategies developed in Europe in recent decades. The so-called social investment paradigm conceives welfare not only as a safety net, but also as a tool capable of promoting both economic competitiveness and social inclusion (

European Commission 2013;

Morel et al. 2012;

Jenson 2009). This paradigm values individual responsibility and activation, placing ALMPs at the center of public intervention. The main objective is to expand employment opportunities by providing people with the necessary tools to face the labor market independently, rather than merely mitigating its risks (

Cantillon and Van Lancker 2013). In turn, employment can contribute to promoting social inclusion by improving participation in social and economic systems

1 which, in turn, facilitates the integration of individuals into a community (

Segers et al. 2023). From this perspective, social spending is understood as an investment in the future of citizens, capable of contributing to a more equitable and inclusive society by promoting employment and reducing inequalities (

Hemerijck et al. 2016).

Active labor policies generally comprise three main types of interventions:

- -

Employment services,

- -

Training courses,

- -

Job-creation initiatives.

Within this macro-category, upskilling programs such as job-oriented vocational training are designed to strengthen, upgrade, or adapt individual skills to market demands. Such interventions reflect a dual purpose: on the one hand, to respond to economic needs; on the other hand, to promote the development of human capital.

ALMPs can benefit all individuals; they are particularly relevant for some groups, such as NEETs. Although NEET rates have decreased in EU countries, this condition continues to represent a significant challenge. Moreover, NEET rates vary significantly by geographical area and individual characteristics. They are particularly high in Italy. For instance, according to Eurostat’s 2024 data, in Italy 27.4% of the population aged between 15 and 34 years fell into the NEET category. This is the second highest quota in an EU country (second only to Greece). Some profiles are more exposed to the risk of being NEETs, such as people with low educational attainment, youth suffering disabilities, people living in rural areas, and especially young people with an immigration background (

Eurofound 2012).

The importance of addressing NEET phenomena is also linked to the fact that it is associated with long-term risks, including deteriorating health, long-term “scarring” effects and insufficient labor supply in the context of aging workforces (

Ralston et al. 2021). In addition to the direct impacts on employment, NEET status also has secondary consequences. For instance,

Sveinsdottir et al. (

2020) found that getting out of NEET status brings improvements in mental health and, subjective perceptions of well-being and reduces drug use. Similarly,

Patel et al. (

2020) observed that participants in a youth employability program maintained a more positive outlook on the future, with higher levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy than the control group, which showed a more negative trend.

To ensure effective support for young NEETs, the literature highlights the importance of tailor-made interventions designed according to their background and specific needs (

Stea et al. 2024). To mitigate this phenomenon, vocational training and on-the-job learning have emerged as key tools for the reintegration of vulnerable groups, such as NEETs. Training experiences, internships and mentoring have emerged as policy interventions that can positively influence the life course of young people (

Alegre and Benito 2014). In particular, programs that integrate multiple components, such as classroom lectures combined with internships or work experience, are among the most effective (

Mawn et al. 2017) when compared to traditional intensive training programs (

Alegre and Benito 2014). According to

Ehlert et al. (

2012), the most effective interventions combine individual coaching, classroom training and temporary work programs. Consistent with these findings,

Mawn et al. (

2017) pointed out that multi-component approaches are generally more effective in increasing employment rates than interventions focusing on only one aspect. In fact, more conventional training programs often fail to achieve the desired results as they are perceived as a replica of formal education (

Bloom et al. 2010). Moreover, the awarding of an official certification at the end of training is considered a key factor for success (

Manfredi et al. 2010).

Finally, it must be stressed that the effectiveness of such programs may vary depending on the characteristics of the participants. Positive impacts are often more pronounced among women, young people, people with unstable housing and individuals with low or lower education levels (

Stea et al. 2024;

Robert et al. 2019). Training courses have also emerged as particularly useful for other groups within the NEET macro group, including refugees. Empowerment through education and training is essential for their integration, although if refugees are not actively involved in the development process, training and employment services may be perceived as passive experiences, limiting their effectiveness (

Tomlinson and Egan 2002). Moreover, in their case, further limitations arise due to the non-recognition of certain qualifications and certificates obtained in their country of origin, which makes qualifying for training courses in the country of arrival important for integrating into the labor market.

1.5. The Goals of This Contribution

Considering the above situation, it is therefore necessary to investigate the actual barriers to the process of confiscation, requalification, and reuse of assets, as well as the levers that can be activated to improve the impact and governance of the multiple stages of the process.

In this context, this study demonstrates how these problems can be addressed and outlines the practical implications within the process.

The contribution presented in this paper, with the aim of increasing the number of redevelopment actions of confiscated assets, accelerating the attribution of social value to these assets over time and extending the social impact of the requalification interventions in the field of professional training for students and the professional qualification of vulnerable people,

- -

fills this gap by providing a clear framework of the main critical issues and needs in the management of confiscated assets by Italian municipalities, to address a solution aimed at the real needs of key stakeholders (public institutions, third sector and citizens);

- -

defines an innovative win–win model, called the “Co-WIN model”, for the requalification process of confiscated buildings, aimed not only at overcoming the current obstacles of the process, but also delivering social benefits for various stakeholders (municipalities, non-profit organizations, educational institutions, and construction companies), vulnerable people and communities.

The Co-WIN project encompasses several aspects highlighted in the previous paragraphs. In fact, it is a multi-stakeholder initiative that provides on-the-job training opportunities preceded by preliminary courses with certification. Simultaneously, it contributes to the training of prospective workers in an expanding sector of the Italian labor market, such as the construction sector.

The contributions presented in this paper comprise the research results from the Co-WIN “Cantieri di cooperazione sociale win-win per la riqualificazione degli immobili confiscati alle mafie e l’equità sociale”

2 research project, funded by the “Polisocial Awards 2021” of the University Politecnico di Milano, which annually finances projects as part of its social responsibility program. The 2021 edition of the competition focused on the theme “Equity and Recovery”, and the proposed projects aimed to develop methods, strategies and tools capable of reducing social imbalances, favoring access to resources and opportunities for vulnerable people, categories or communities, with a view to equity and sustainability.

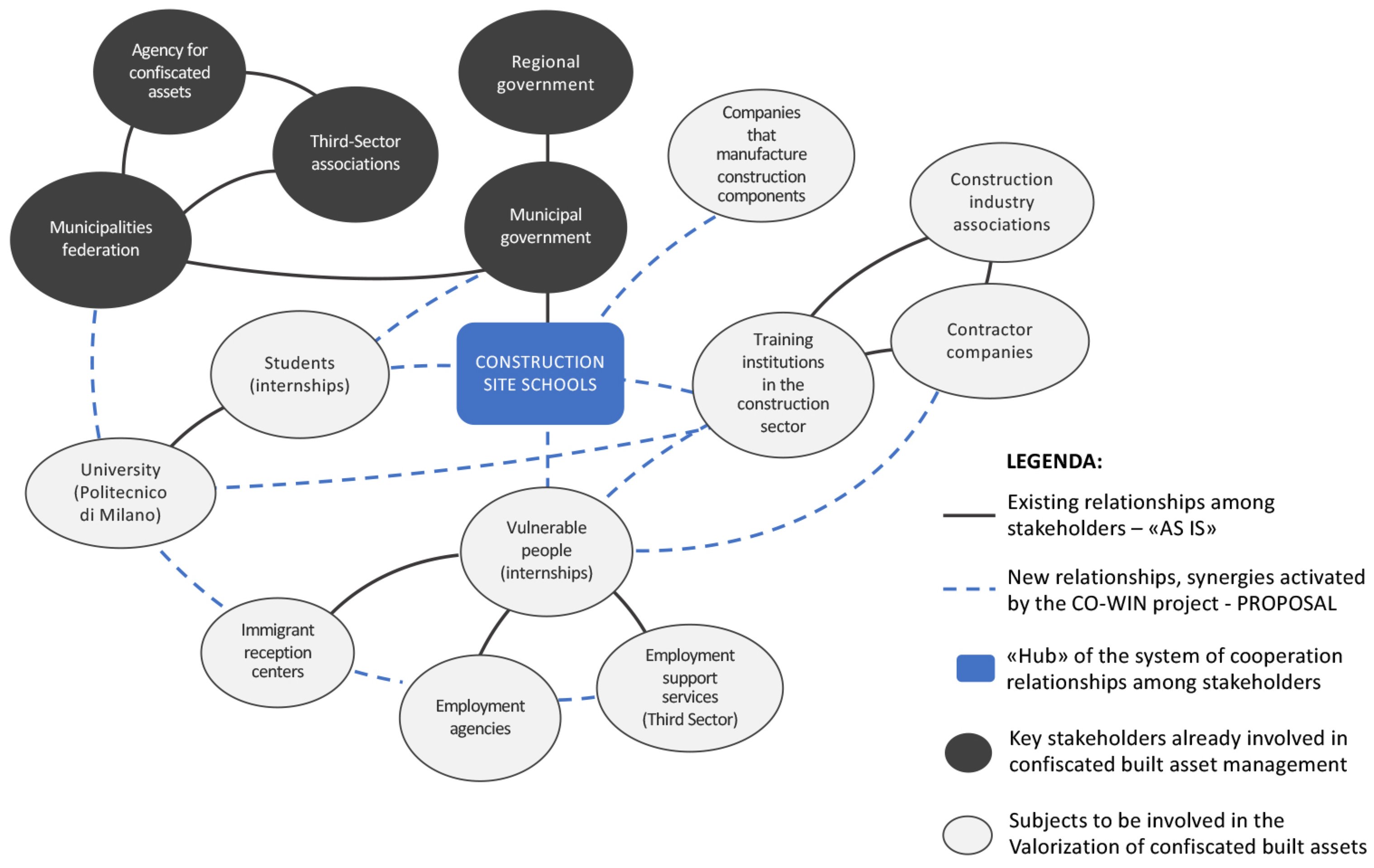

The research of Co-WIN focuses on the Lombardy Region territory for the development of an innovative “hub-and-spoke” model for the confiscated built asset reuse issue, that became “construction site schools” for social integration, educational and technological experimentation through multistakeholder networks based on win–win logic (

Campioli et al. 2024).

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the data and methodology used to analyze the critical issues and needs of confiscated built assets, and defines the win–win strategy for the innovative model and the activation of construction site schools in the pilot projects.

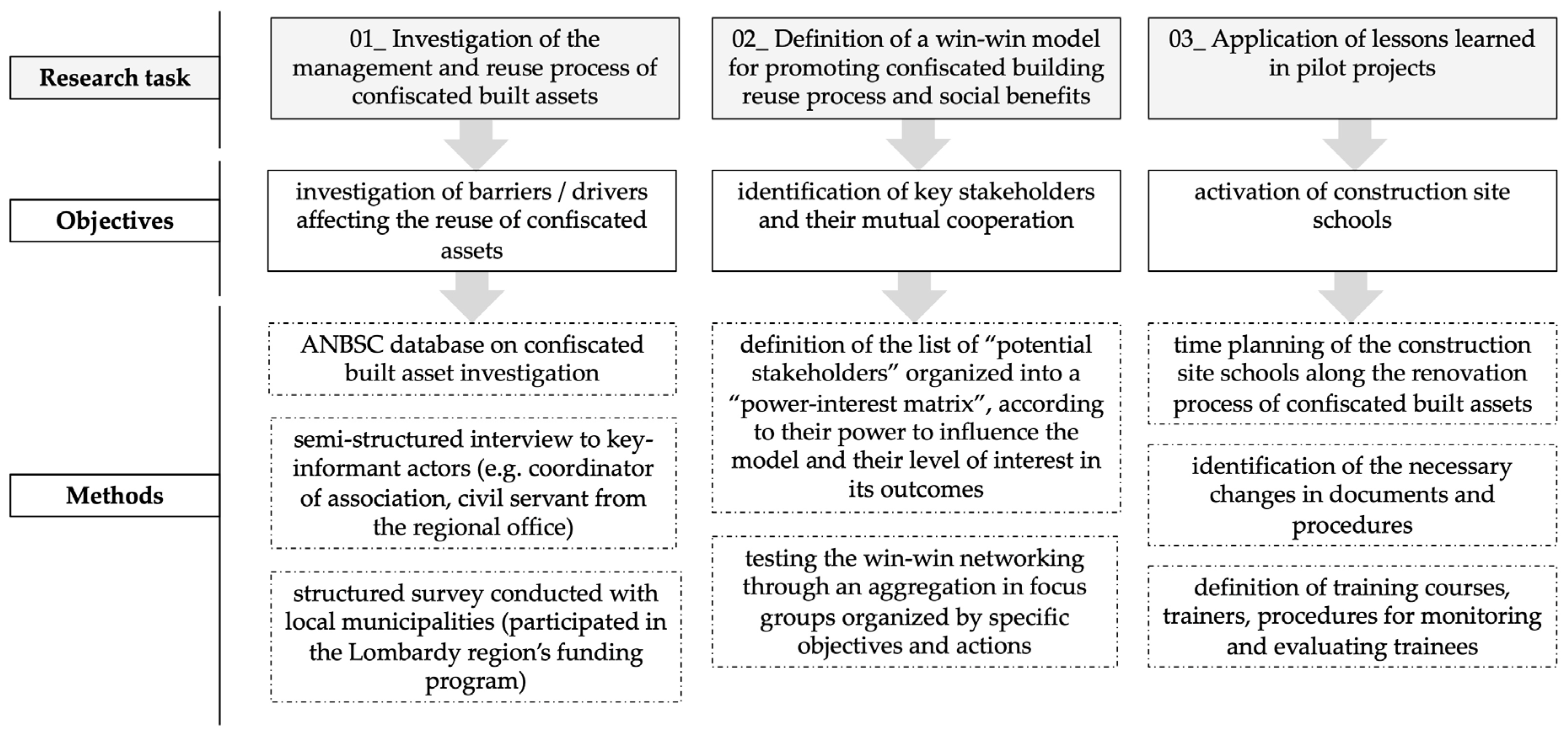

Figure 2 illustrates the research procedure, which was divided into “research phases–objectives–methods”, to facilitate replication by other researchers. The following paragraphs provide further details on the data and methods used in the three research phases.

2.1. The Investigation of Barriers and Drivers Across the Management and Reuse Process of Confiscated Built Assets

Three main sources were used to assess the scale of the phenomenon and identify the key barriers and drivers that influence local governments in taking up and reusing confiscated assets:

The ANBSC database on confiscated built assets, including their types and locations;

Semi-structured interviews with key informants;

A structured survey conducted with local municipalities.

Key informants included the coordinator of an association dedicated to supporting local authorities and the ANBSC in the management of confiscated assets, assessing business development opportunities, and proposing organizational transformations (key informant #1), an official from the ANBSC (key informant #2), as well as a civil servant from the regional office responsible for overseeing regional funding for the renovation of confiscated assets (key informant #3).

To further explore the dynamics of the decision-making process and asset management by local authorities, a structured survey was distributed to municipalities that had participated in the Lombardy region’s funding program for the recovery of properties seized from criminal organizations. The survey, conducted in March and April 2023, targeted all municipalities that had received funding through calls in 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022.

The objective of the survey was to gather and analyze the diverse experiences of Lombardy municipalities in managing confiscated assets, as well as to identify their needs and challenges. The questionnaire was divided into the following sections:

Characteristics of the confiscated assets;

Structural interventions;

Expertise in activating and managing the confiscated assets;

Reuse of assets;

Support from entities and institutions;

Citizen involvement.

The survey was administered online using the Microsoft Forms platform. A total of 49 municipalities were contacted, with the questionnaire specifically targeting the offices responsible for overseeing the conversion of confiscated properties. Forty-four full responses were received. Some municipalities had multiple confiscated assets, and the survey gathered insights from their experiences with all such properties.

2.2. Definition of a Win–Win Innovative and Replicable Model for Promoting the Confiscated Building Reuse Process and Social Benefits

To define a win–win innovative and replicable model related to the issue of confiscated built asset management, a multidisciplinary approach is needed. The win–win approach has raised the interest of scholars and practitioners in several disciplines, including economics, business, game theory, policy, social sciences, and engineering (

Altarawneh et al. 2022), and it is often represented as an application of the non-zero-sum game theory (

Dyhrberg-Noerregaard and Kjaer 2014). Application of the win–win approach in research has primarily been based on the stakeholder integration theory (

Plaza-Úbeda et al. 2009) and the application of a “power/interest matrix” for stakeholder mapping and classification (

Scholes et al. 2001;

Elsaid et al. 2017).

In particular, the multidisciplinary approach allows the following aspects to be addressed: (i) the heterogeneity of the project research areas; (ii) the different competencies of the stakeholders, understanding their potential and mutual win–win strategies; (iii) the legislation related to the process of renovation and reuse of confiscated assets; (iv) the rules and standards for the involvement and training of vulnerable people.

The key stakeholders involved in the Co-WIN model were identified on the basis of possible mutual cooperation, looking for different characteristics with regard to priority needs, such as

valorization of the renovation processes of confiscated built assets;

inclusion of vulnerable people to enable enhancement of their training and work skills;

identification and provision of mandatory and optional specialization training to vulnerable people;

activation of curricular internships for on-the-job training of students.

To identify the Co-WIN stakeholder network, an initial list of ‘potential stakeholders is organized into a ‘power–interest matrix’, used as a strategic framework to categorize stakeholders according to their power to influence the model and their level of interest in its outcomes.

The matrix enables a quick classification of stakeholders, which is useful in understanding the win–win relationships that can be activated through networking. From this classification it is also possible to structure an effective communication plan aimed at engaging, informing, and involving stakeholders.

To define and test the win–win networking, the stakeholders are aggregated into “focus groups” organized by specific objectives and actions.

To achieve the goal of the Co-WIN model, the proactive participation of all stakeholders through the creation of a strong and stable network of relationships is essential.

2.3. Application of Lessons Learned in the Pilot Projects

At the same time, the timing of the construction site school model was planned, intercepting, along the renovation process of confiscated built assets, the necessary changes in documents and procedures (e.g., changes to the public tender, additional contractual clauses between process operators, and recruitment of vulnerable people).

Through the activation of four pilot projects, located in Lombardy municipalities that had obtained funding to support the renovation of confiscated buildings, the Co-WIN model and construction site schools were developed and tested.

Specific training models, tailored to the context and social categories to be trained, were also developed to activate the construction site schools. In this context, mandatory and optional specialization training courses to be delivered to trainees, persons who can play the role of trainers, and procedures for monitoring and evaluating trainees were defined.

Finally, a digital learning course (MOOC) was established to transfer the experience of construction site schools to the classroom at the university level.

3. Results

3.1. Drivers and Barriers to the Renovation and Reuse of Confiscated Built Assets

3.1.1. Quantification of the Assets

Confiscated asset portfolios consist of two main categories: real estate and businesses. This section focuses on the former, as they are the subject of the Co-WIN project.

In Lombardy, the total number of assets seized and confiscated from organized crime is 3320. Of these, around 40% (1353) are still managed by the ANBSC, while 1967 have already been transferred to other entities (

ANBSC 2024).

According to ANBSC data, updated in December 2024

3, the most common model for transferring confiscated assets is to local municipalities. In fact, three-quarters of the earmarked properties have been transferred to local governments, while approximately 13% have been assigned to State property. Of the latter, two-thirds are used by the Armed Forces. Approximately 10% are undergoing sales procedures.

The most common type of asset (see

Table 1) is apartments in condominiums, along with garages and storage units. This applies to both earmarked assets and those managed by ANBSC. These are typically small-sized units, which has implications for the reuse strategies that can be planned. It is worth noting that, in some cases, the apartments are part of entire buildings that have been confiscated, while in many others they are located in condominiums where other units are not confiscated and are still inhabited by private owners.

As already mentioned, the regulations stipulate that the reuse of assets confiscated from organized crime must serve mainly social purposes. In fact, 71% of the assets transferred in Lombardy are designated for social purposes. A smaller proportion (15%) is used for institutional purposes. This latter category is particularly common among properties transferred to the State, which, as noted earlier, are often used by the Armed Forces as institutional headquarters. Assets that are used to satisfy creditors are those put up for sale.

3.1.2. Barriers

The management and repurposing of confiscated assets pose significant challenges, particularly for local governments, which are the primary actors receiving these properties. These challenges include securing the necessary funding for renovations, finding suitable third-sector organizations to manage the assets, and ensuring that repurposed properties meet local needs.

Renovations and Securing Required Funding

One of the main difficulties faced by municipalities is securing adequate funding for the renovation of confiscated properties. Poor building conditions further exacerbate the situation. Municipal technical departments are generally responsible for assessing the costs of renovation. According to the survey of municipalities that participated in the regional call for funding from 2019 to 2022, 23% reported receiving assets in unusable condition, while 36% received properties in structurally poor condition. This highlights the substantial obstacles that municipalities face when tasked with converting confiscated assets into community spaces.

Regional funding is helpful in this regard but typically does not cover the full cost of renovations, so municipalities must find additional resources. In most cases (38 of the 44 municipalities surveyed), these funds come from their own budgets. A potential strategy would be to secure additional private funding to finance part of the renovation costs. However, many municipalities lack experience with participatory financing tools, such as civic crowdfunding, or with applying for funding from external sources, like private foundations, making it difficult to secure additional financial support. Indeed, only 2 municipalities among the 44 respondents of our survey have received private funding for renovation. In contrast, many municipalities, particularly smaller ones, highlighted the lack of the required financial expertise among their staff. The majority of municipalities in our survey reported having low to moderate knowledge of financial tools, including participatory financing options like crowdfunding (

Table 2). As a result, it is not surprising that external funding for renovation remains limited.

Additionally, it must be considered that, in the long term, the buildings will require further restoration. Leaving those costs in the hands of the third-sector organizations to which the assets have been assigned may not be feasible, particularly for smaller organizations, making it more difficult to find groups willing to take on the responsibility. As a result, these future costs would likely be absorbed by the municipalities’ budgets.

Finding Suitable Management Organizations

A further major challenge is finding third-sector organizations that can manage and operate repurposed assets. The third sector in Italy is unevenly distributed (

Andreotti and Mingione 2013), with some areas lacking sufficient local operators. Smaller municipalities often struggle to attract organizations that are willing to operate in areas with limited populations. This issue is not confined to small municipalities; even medium-sized ones face similar difficulties according to our interviewees. To address this, many municipalities are focusing on projects that target a broader, supra-municipal audience. In fact, nearly 50% of municipalities in the survey reported that the target user base for repurposed assets extends beyond their local area. In any case, approximately 20% of the municipalities reported struggling to find third-sector organizations willing to take on the management of repurposed properties.

Concerns about the difficulty of finding interested third-sector operators can discourage local authorities from accepting the transfer of confiscated assets. To address this, key informants highlighted a useful practice: issuing a preliminary call for interest before formally assigning an asset to the municipality. This approach allows local authorities to assess whether there are third-sector organizations willing and capable of managing the property, based on the results of this initial phase.

Once assets are allocated, the key challenge becomes ensuring the long-term financial sustainability of reuse projects. The economic sustainability of projects implemented in assigned properties is crucial to ensuring that their social impact is long-lasting and meaningful. The interviews with key informants often highlighted the lack of attention to economic sustainability in some projects, particularly by smaller third-sector organizations. In this regard, it was pointed out that second-level organizations, such as umbrella associations, could play a more significant role in supporting smaller entities. However, this is not always the case, as one interviewee noted: “Second-level organizations are truly shortsighted. Instead of leveraging expertise, they want the tools without understanding them… they want the model without knowing how to apply it…” (key informant #1).

The difficulties in managing and financing the repurposing are also related to the dimensions of the properties involved, with the largest ones being a particular issue. These properties may require the accommodation of multiple activities, which complicates the identification of organizations capable of handling such complex projects. As a result, some municipalities form consortia of organizations, but this adds additional management challenges.

Coordinating the Repurposing Process

Effective coordination between municipal departments is essential for ensuring that the renovation and repurposing processes align with local needs. Physical redevelopment and asset assignment should not be viewed as independent phases. Physical redevelopment should be coordinated with a reuse strategy. However, a lack of coordination between technical departments (e.g., construction and maintenance) and social services can lead to inefficiencies. Among the municipalities financed in the 1999–2022 period, in almost half of the cases only the technical offices were involved in carrying out property valuations while in around one-quarter of the municipalities, social services were also co-involved at that stage

4. The lack of such coordination risks leading to physical and structural renovations that are inconsistent with the intended future use, which may require additional work or necessitate changes in the physical environment to meet the actual needs of the reuse strategy.

The same coordination would be helpful between municipalities and the providers of future activities to be hosted in the property once it is restored. For example, 77% of the municipalities in the survey reported that social services were the primary department involved in defining the new use for the property. In approximately one-third of the cases, third-sector organizations were also involved in this stage. However, it is still relatively uncommon (only 17% of municipalities) for municipalities to issue a call for interest to the third sector before finalizing the renovation plan. Doing so could help to identify the needs and interests of potential users, which could influence the renovation and repurposing strategies. This underscores the need for municipalities to build relationships, including strategic ones, with the third sector, which is sometimes missing. As one key informant (#1) put it: “Municipalities need to understand that the third sector is an asset, they are partners, not just mere executors”.

Despite the ongoing challenges mentioned, one key informant highlighted that these issues have lessened over time: “The major problems were encountered in the early years. Now, municipalities have generally gained more awareness. When a municipality acquires a property, it already has a project and a clear idea of its potential use. In the beginning, this level of awareness was lacking. Over the years, many training courses have been offered to municipalities, including by the Region and ANCI (National Association of Italian Municipalities), to address these issues. In the past, it was common for municipalities to accept a property without a clear plan for its repurposing, and then struggle to determine how to allocate it” (key informant #2).

3.1.3. Drivers

One of the key themes driving the repurposing of confiscated assets lies in the relationship between their new use and their previous identity. Through this new purpose, these assets are returned to the community, and those who utilize them become a symbol of this restitution: “The community takes part in a story of the State’s revenge” (

Dalla Chiesa 2016).

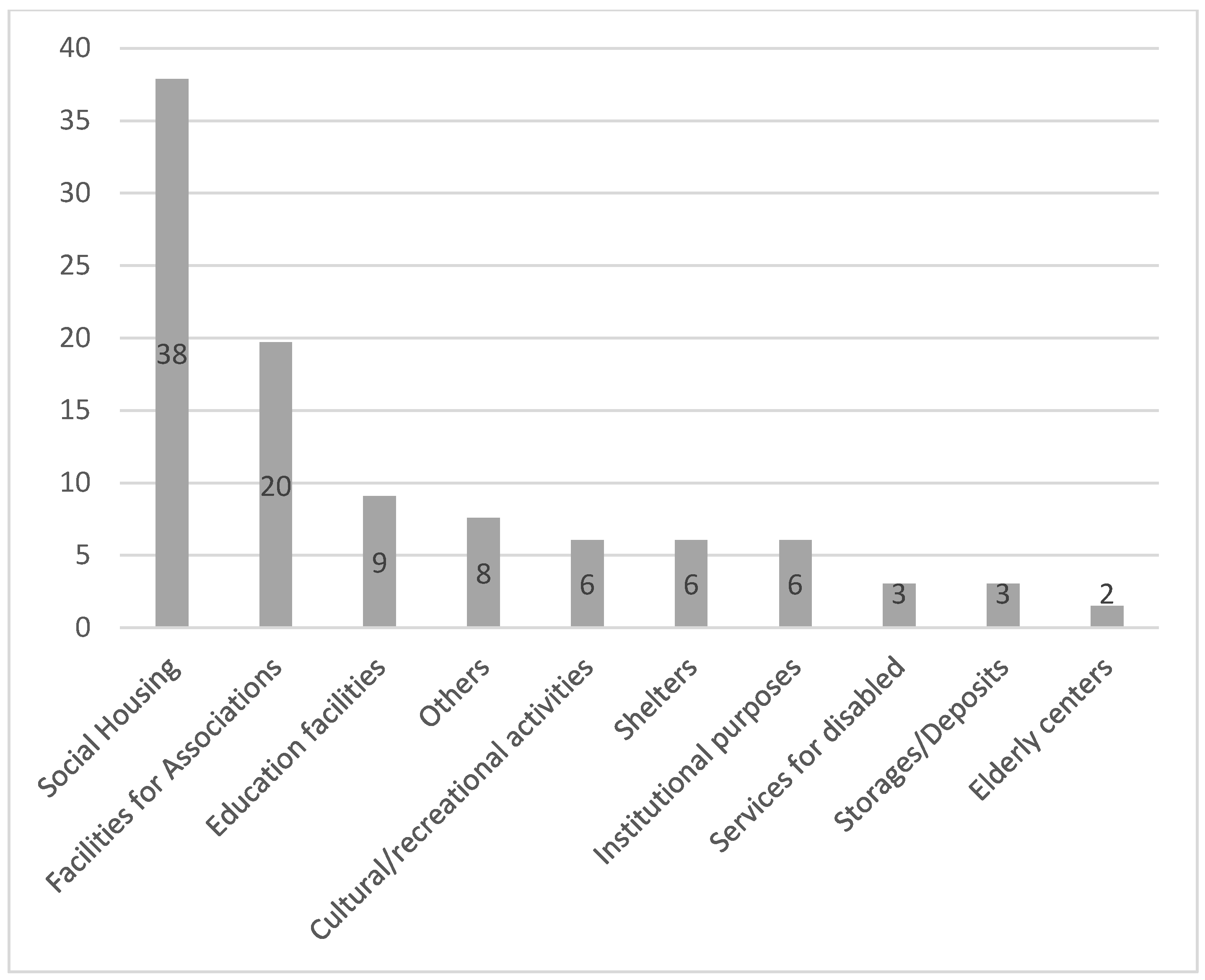

Two key points emerge in this context. On the one hand, there is the question of the new use of the assets. These properties are transformed into valuable assets that can host social activities, benefiting the entire community. Social housing and spaces for local associations are the most common uses for these assets (see

Figure 3). The choice of these types of uses is closely linked to the architectural nature of the buildings that municipalities are tasked with repurposing. As previously noted, many of the properties transferred to municipalities are apartments, making their conversion into social housing a natural fit. This also addresses one of the most pressing challenges in our cities today: the housing crisis in an increasingly expensive rental market (

Bricocoli and Peverini 2024).

On the other hand, the awareness of the property’s previous use and the journey it has undergone to reach its new purpose can play an important role in the process. This awareness can be promoted through plaques placed outside the property, or, more extensively, through activities that connect the asset’s history to its new function. In some cases, third-sector organizations managing the properties maintain ongoing relationships with associations involved in combating organized crime. These organizations often run courses and events that engage the local community hosted within the newly transformed asset. In other cases, the concept of “redemption” and the property’s return to the community are central to its new use. An exemplary case is the Masseria di Cisliano, part of the Co-WIN pilot projects, where even before the official assignment of the property it was used for training courses on the conversion of confiscated assets and for volunteer activities involving young people, including structural conservation work on the property.

Furthermore, repurposing a confiscated asset can foster dynamics and mechanisms aligned with social entrepreneurship, which combines business-oriented activities with civic, solidarity-based, and socially useful purposes. Through activities carried out in the confiscated property, it is possible to generate profits that help self-finance the operation, thereby increasing its sustainability, or to support additional activities hosted within the property. This can also lead to the creation of new jobs.

Finally, citizen involvement in co-design processes is seen as an interesting potential but concerns about feasibility also emerge. In fact, 35% (half of those who find these processes interesting) consider them difficult to organize and manage while only three administrations have actually organized them. Organizing events open to the public to raise awareness about confiscated assets and their reuse is seen as more manageable. However, these initiatives are also seen as challenging by some municipalities. While a considerable number of municipalities accessing regional funding between 2019 and 2022 are considering developing similar initiatives, only nine have already organized such events and a quarter of those surveyed find them interesting but difficult to implement (

Table 3).

3.2. The Definition and Application of the Co-WIN Model

The conceptualization of the Co-WIN model recognizes the important social value of reusing confiscated built assets, which involves not only returning built resources to the community through allocation to the third sector (TS) but also triggering social dynamics within the territory.

The Co-WIN model creates a collaborative framework around the renovation project of confiscated built assets, establishing a win–win network, which fosters a shared understanding of the interests, objectives, and the project’s overarching aim among stakeholders.

In this synergistic network, collaboration and cooperation become central aspects, ensuring that the project’s success aligns with the collective interests of all involved parties. This approach, which is particularly relevant for public works, goes beyond individual gains, aiming to create a sustainable and inclusive impact that resonates positively throughout the broader community (

Aaltonen and Kujala 2010,

2016).

The Co-WIN innovative model of intervention for the renovation and reuse of confiscated built assets is based on the construction of a virtuous and structured system of win–win cooperation among diverse type of stakeholders, ranging from government bodies and local authorities to community groups and residents, as well as to vulnerable people and students, where education and training is part of the objective.

The proactive structured system of relationships acts as an activator of virtuous win–win processes on multiple occasions of renovation and reuse of confiscated assets (

Nielsen 2009;

Eshun et al. 2021).

In fact, the Co-WIN model triggers territorial social dynamics that result in teaching–learning experiences involving vulnerable people, undergraduate students and operators with specific technical skills. The category of “vulnerable people” generally includes more NEET (“not in education, employment, or training) young people, unemployed people with or without previous experience in the construction sector and, more specifically, refugees and migrants (who are more at risk of being exposed to the risk of becoming NEETs, as seen in

Section 1.4). The category of “operators with specific technical skills” includes construction value chain practitioners, such as designers, construction managers, constructors, and municipality technical officers.

To this end, the Co-WIN model introduces a construction site school experience during the construction phase of the renovation process of confiscated buildings. Construction site schools offer a temporary training experience where trainees can acquire new individual skills through a combination of theoretical and practical activities. They provide an “on-the-job” training opportunity, involving trainers and trainees on the construction site.

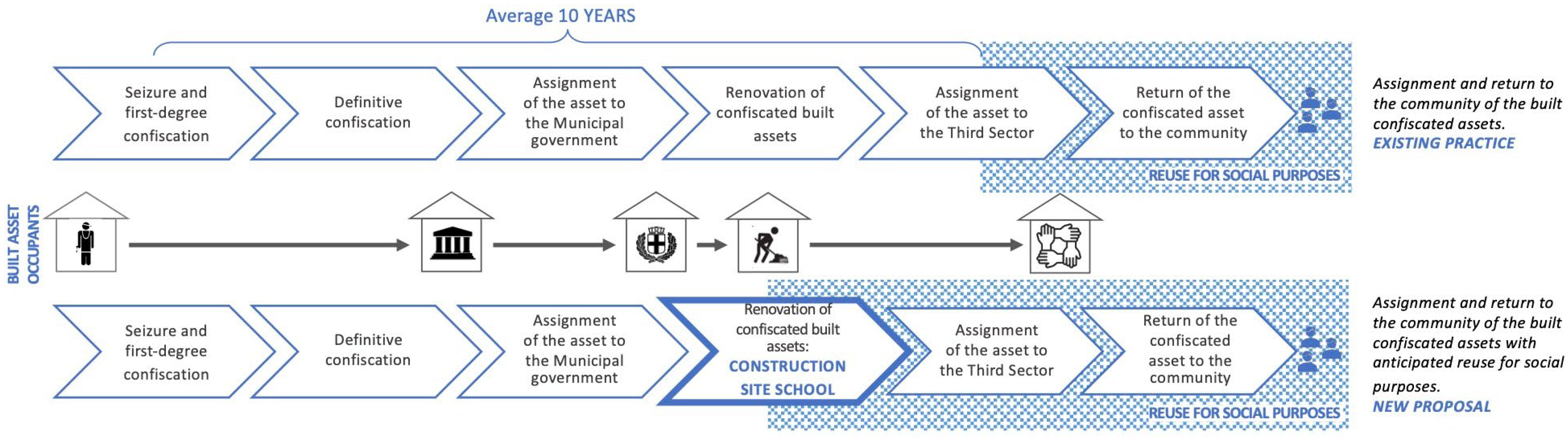

Through the activation of construction site schools, the social benefits of the requalified assets not only occur during the building reuse phase but are anticipated during the renovation phase (

Figure 4).

Co-WIN construction site schools are an opportunity for vulnerable people to train and access the labor market while, at the same time, being an opportunity for students in construction degree programs to carry out a technical–operational internship, as is mandatory, amounting to 100–150 h of training (the number of hours depends on the educational course).

This network facilitates both the integration of vulnerable people into the labor market and the creation of new skills. The creation of new skills addresses the urgent need of the Italian construction sector, which is currently struggling to find manpower amid a constantly growing demand for labor (

ANCE 2022). In addition, a current need of the construction sector regards specific skills related to the increasing number innovative construction solutions and techniques.

The network between different stakeholders activates the construction site schools, innovating the building process by creating relationships among different stakeholders that do not occur in the conventional process (

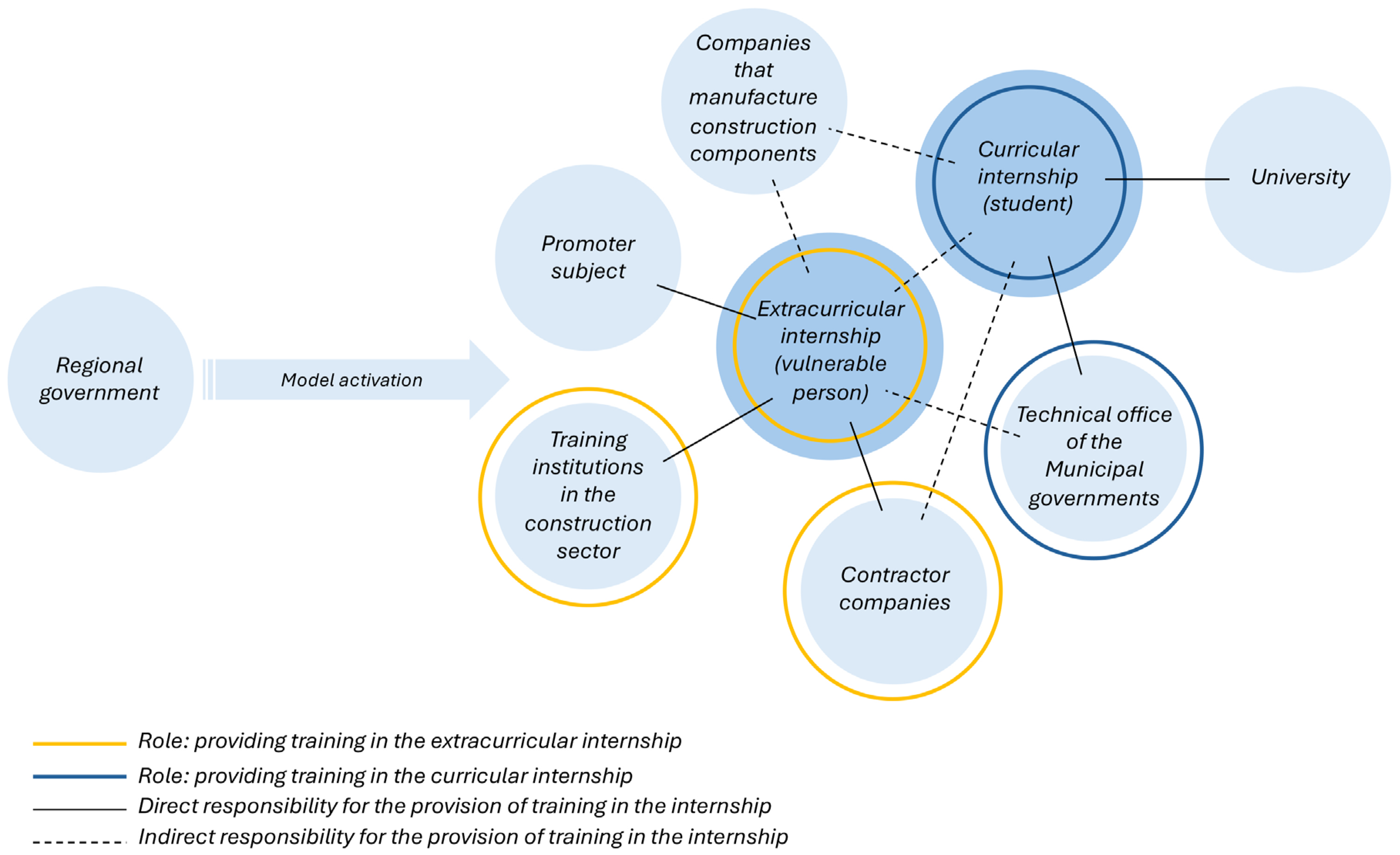

Figure 5).

The change in relationship and in the conventional process needs changes in both the documents and procedures across the building requalification process, and the definition of the training program for the construction site school based on the social categories involved (i.e., vulnerable people and university students).

3.2.1. Necessary Changes in Documents and Procedures to Activate the Co-WIN Model Pilot Project

The introduction of the Co-WIN model and the activation of construction site schools with the involvement of vulnerable people and university students was tested through pilot projects, activated in four municipalities in the Lombardy region: Settimo Milanese, Trezzano Sul Naviglio, Gerenzago and Cisliano.

To enable the activation of construction site schools and multi-stakeholder networks in the current building process, a preliminary study of national legislation, tender procedures, contracts and building instruments was necessary. This led to the identification of necessary changes in administrative acts and contractual clauses (Contracting Authority/Contractor) that enable the recruitment of trainees within construction site schools.

In particular, the activation of the Co-WIN model within the process of renovating confiscated assets requires (i) the “official document” of adhesion to the Co-WIN model by the public administration; (ii) specific additional clauses to be included in tender documents and contract schemes; (iii) the elaboration of contract formulas for the inclusion of vulnerable people in construction site schools; (iv) agreement between the municipality and manufacturers, who offer free supply of construction products.

(i) The municipality publishes an “official document” (Delibera Comunale), as a public act, by which the City Council and Administrative Council formalize membership in the ‘Co-WIN model network, which entails obligations and grants within the renovation of confiscated built assets.

In fact, joining the Co-WIN model obliges the municipality to activate internships for university students within the construction sector, as well as obliges contractors to activate internships for vulnerable people.

In addition, joining the Co-WIN model grants the municipality a free supply of materials for use in the renovation of the confiscated property.

(ii) These obligations and grants must be introduced in the calls for tenders, in the contract specifications, and in the contract schemes. These additional clauses are defined by involving the legal support of the ANAC (Italian National Anti-Corruption Authority) and Assimpredil Ance (Association of Building Construction Companies).

(iii) Regarding the elaboration of contract formulas for the inclusion of vulnerable people in construction site schools, a preliminary study of national legislation (L. 8 November 1991 n.381- Disciplina delle cooperative sociali) and regional legislation (Delibera X/7763 del 17 January 2018—Indirizzi Regionali in materia di tirocini) was carried out. After evaluating the different alternatives, the extracurricular internship was selected as the best contractual formula between vulnerable people and the construction company (host party) carrying out the renovation work on the confiscated building.

According to regional regulations, the extracurricular internship provides up to six months of contract for vulnerable people, paid with a minimum contribution (500 EUR/month working 7 h/day). As the Co-WIN pilot projects uncovered that this minimum remuneration is not sufficient for the involvement of vulnerable people, and the work on construction sites should be extended to 8 h, as performed by the rest of the construction team; it is important to emphasize that it is possible to increase the minimum remuneration through public funding opportunities or through an additional salary provided by the host party (construction company). Additional work hours could be covered by insurance provided by the construction company.

In the Co-WIN model, the third sector, involved in finding job opportunities for vulnerable people, monitors additional funding opportunities to support construction companies for the placement of vulnerable people by increasing the minimum monthly payment stipulated in the regulations for extracurricular internships.

The regulation of extracurricular internships defines the number of traineeships that can be activated in a company, which is proportional to the number of employees in the company. However, if the trainees belong to the social category of vulnerable people there is no limitation on the maximum number of eligible trainees in a company. This may increase the social impact of the Co-WIN model in the national context.

On-site professionalizing experience aimed at university students is realized through the activation of technical–operational curricular internships within the municipalities that own the confiscated built asset undergoing renovation. The formula for curricular training and orientation internship is defined by Interministerial Decree No. 142/1998.

(iv) Finally, an agreement is established between the municipality and the manufacturer, who offers free supply of construction products within the construction site schools, for the purpose of research and experimentation, as noted in their ESG report. The free supply of products by manufacturing companies is a key lever for the activation of the Co-WIN model, as it provides an economic incentive for the municipality.

3.2.2. Training Program of the Construction Site School According to the Social Categories Involved

Construction site schools promote the employment of jobless or vulnerable people in public benefit activities, which is provided in Italian Law No. 264 of 29 April 1949 (Art. 59 ff., later supplemented by Law No. 418 of 6 August 1975) and regulates the placement of workers without income support (

Leardi 2021).

Through the enactment of Presidential Decree No. 616 of 24 July 1977, the responsibility for the opening and management of construction site schools—still exercised by central state bodies or national and interregional public agencies—was transferred to regions with ordinary status.

The activation of the Co-WIN construction site schools requires the definition of procedures and methodological aspects, in terms of the educational project, adaptable to the project and construction works of construction site schools, and training method that establishes roles and responsibilities of key players who educate and evaluate the level of skills learned by trainees.

3.3. Educational Project for Students

The educational project for students requires the support of the municipality: The students work alongside the project manager of the renovation process, or alongside the designer and the construction manager, working on the confiscated built asset.

The internship, carried out directly in construction site school, enables university students to experience the procedures of construction sites and understand all the procedures related to public works, starting from the planning of works by public agencies, through the design phase, the publication of public tender for construction works, and the construction phase to the conclusion of the process.

The training activities also include collaboration with designers, reviewing and monitoring design activities, assisting in the preparation of tender documents for the award of construction work, supporting the project and construction managers in the activities of directing and monitoring construction work, and following up with testing and building assignments.

The trainee, through the construction site school experience, acquires technical, operative, administrative and communication skills.

For the Co-WIN pilot projects, students were recruited through the Career Service platform of the Politecnico di Milano and interviewed for selection. The student trainee was supported by a “business supervisor”, who was the technical office of the municipality involved, and by an “academic supervisor”, who was a university professor and who validated the educational project.

3.4. Educational Project for Vulnerable People

Vulnerable people are provided with mandatory and optional specialization training to attend before starting their construction site school experience. All courses are offered free of charge by the training institutions that are part of the Co-WIN network.

The educational project for vulnerable people is established in relation to the works that characterize the building renovation construction intervention; therefore, it is necessary to define a flexible training course that can be adapted to the project and construction works for each Co-WIN construction site school.

The training project specifies both the level of competencies (in terms of knowledge and skills) and the level of responsibility and autonomy that trained vulnerable people can acquire (

Table 4). These levels are based on

the “European Qualifications Framework” (EQF), a learning outcome-based framework which enables comparison of qualifications from different countries and institutions; it covers all types and all levels of qualifications and clarifies what a person knows, understands and is able to do.

the “Regional Framework of Professional Standards. Professional Profiles and Autonomous Competencies Section” of the Lombardy region, in accordance with the “National Directory of Professional Titles and Qualifications”, which defines theoretical and practical knowledge and, cognitive and practical skills for each task in various sectors, including construction.

The Co-WIN training pilot projects aimed to qualify the extracurricular trainee with EQF Level 3 “Certificate of Professional Operator Qualification”, defining the theoretical knowledge and cognitive and practical skills to be acquired by the trainee.

The training plan of the Co-WIN pilot project construction site schools was based on the list of construction works planned for the renovation of a confiscated building, and specified for each type of construction work (e.g., installation of thermal insulation coating systems and interior and exterior finishing works on walls) the theoretical and practical knowledge and cognitive and practical skills, in accordance with the “Regional Framework of Professional Standards”, that can be acquired by the trainee to reach the EQF3 level of training.

For the Co-WIN pilot projects, vulnerable people were recruited through cooperation with third-sector actors engaged in the Co-WIN network. The first selection of trainees was conducted by the third sector, and the confirmation of recruitment followed an interview conducted between each vulnerable person, the third sector and the construction company in the presence of the Co-WIN researchers.

Training Model: Roles and Responsibilities of Trainees

The innovative training model of Co-WIN construction site schools considers the interaction of both curricular trainees (university students) and extracurricular trainees (vulnerable people), simultaneously involved in the renovation process of confiscated buildings.

University students can get involved from the early design stages and can follow the entire building process. Vulnerable people are involved during the construction phase, becoming part of the construction team.

Activating the professionalizing training course for university students and vulnerable people requires a framework of relationships between different operators (trainers) and support tools for monitoring and evaluating the skills and responsibilities acquired by the trainees.

All operators involved in the construction site schools play a role in supporting and mentoring trainees’ learning and/or monitoring and evaluating them.

Figure 6 shows all the operators involved in the Co-WIN construction site schools, highlighting

Who plays the role of trainer of an undergraduate student and then monitors and evaluates their progress in skill acquisition during the internship experience;

Who plays the role of trainer of a vulnerable person and thus monitors and evaluates progress in skill acquisition during the internship experience;

Who has direct responsibility for the learning of students and vulnerable-person trainees (e.g., when the practitioner plays the role of trainer or training management and monitoring);

Who has indirect responsibility for the students’ and vulnerable person trainees’ learning path (when the practitioner interacts with trainees but does not have a decision-making role in their learning);

Regarding the evaluation of the training experience, the trainer who plays the role will evaluate the level of learning achieved by extracurricular/curricular trainees.

For example, in the case of an extracurricular trainee, training institutions may evaluate the trainee’s level of acquisition of theoretical knowledge; furthermore, the construction company may evaluate the trainee’s level of responsibility and autonomy, the acquisition of cognitive and practical skills, and the ability to fit into the workplace (e.g., compliance with rules; work integration, and commitment).

To this end, trainers use tools for monitoring and evaluating trainees, considering the level of skills and responsibility/autonomy acquired. The evaluation tools are artic-ulated based on the training plan, then based on the list of construction work planned for the renovation of the confiscated building.

The training model is complemented by the transfer of the construction site school experience to university courses through the use of digital learning courses.

Based on pedagogical frameworks (i.e., tools that define operational guidelines for the development of a learning pathway) (

Sancassani et al. 2019), operational guide-lines for the design of digital course content were defined, and then the Co-WIN digital course was developed and shared.

The course is open source for all university students, in order to increase the edu-cational impact of the construction site school experience.

4. Discussion

4.1. Framework of Critical Issues and Benefits, and the Identification of Improvement Actions

The results of the investigation and the pilot projects enabled the establishment of a clear framework of critical issues and benefits that emerge from the current process of valorizing confiscated buildings. This framework permitted the identification of some improvement actions that can enhance the replicability of the model, and relevant related important strategies.

Regarding the critical issues that characterize the management of confiscated built assets, the results of this research showed, as a primary complexity factor, the heterogeneity of property types, generally multi-family house, detached houses, garages, warehouses, stores, industrial buildings, etc., and the poor state of preservation of the properties and low levels of energy efficiency. Therefore, the requalification and reuse of confiscated built assets require high financial resources from local authorities, and multidisciplinary skills for the management of legal, technical and economic processes.

One of the main problems is the economic difficulty faced by many municipalities. The confiscated assets they receive often require extensive renovations, not only because they are in poor physical condition but also to adapt them for new purposes. As a result, municipalities need additional funding to manage these properties. In some regions, like Lombardy, regional administrations provide some financial support for municipalities that receive allocations of confiscated built assets. However, this approach is not widespread across the country.

In addition, the economic funds offered by the region typically only cover the renovation phase of the asset, without considering the whole building lifecycle. Management, ordinary and extraordinary maintenance, and all expenses during the use phase (i.e., until the building’s end of life are the responsibility of the municipality, which receives no additional help from the region. As a result, municipalities often decline the allocation of confiscated built assets, citing financial constraints related to renovation and long-term maintenance costs. Moreover, especially for small municipalities, there is a lack of multidisciplinary and technical expertise necessary to face the legal, technical and economic issues of the entire requalification and management process.

Another critical issue identified in the analysis of confiscated built asset reuse concerns the lack of coordination, both within local government departments and between municipalities. Internal coordination is crucial to align renovation activities (typically managed by municipal technical offices or public works departments) with the intended future use (usually determined by social services offices).

Inter-municipal coordination becomes even more critical in a country with many small municipalities, which must plan beyond their immediate local needs by considering a larger scale than the municipality itself, especially in terms of the needs, uses and potential third-sector operators to be involved.

In fact, there is no comprehensive territorial management of social action that could support networking and enhancing reuse initiatives. The absence of a coordinated strategy at the local and regional levels often hampers the effective repurposing of confiscated properties.

Regarding benefits, the reuse of properties confiscated from organized crime represents a significant opportunity to address various social, economic, and security needs within a community. Such processes of revitalization can have positive effects involving several dimensions.

The revitalization of confiscated properties has a significant value in terms of preventing urban decay. Transforming abandoned buildings into usable spaces prevents them from becoming sites of degradation and danger to the community. The regeneration of these properties has been a tangible symbol of resistance and recovery against criminal activity, contributing to the improvement of the urban environment. The repurposing of these buildings for social purposes has also reduced the risk of abandonment and illegal use, instead favoring territorial control and surveillance. This has also acted as a deterrent against further criminal infiltration.

A fundamental aspect regards the reuse of such assets for social purposes. Confiscated properties have provided partial solutions to some local social challenges. A significant portion of the spaces has been allocated to housing services for vulnerable individuals, such as struggling families, the homeless, or elderly people. This can help to reduce pressure on public housing and provide housing solutions in areas where there is a chronic shortage of homes.

Additionally, the reuse of these properties has facilitated the settling of activities by the third sector which, in synergy with local institutions, has been able to offer a wide range of social services to people in need. These services range from healthcare and psychological support to the management of community spaces (

Polis 2016). The presence of the third sector can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals, promoting social integration, and the rehabilitation of marginalized people.

As some of these assets have been assigned to the Armed Forces as their territorial offices, the reuse of confiscated properties has also strengthened their territorial presence in terms of security. In these cases, the restoration to legality of these buildings is complete, as they transition from being a property of criminal organizations to becoming a local presidium of law enforcement authorities.

Equally important has been the employment value linked to the revitalization process. The renovation of confiscated properties has created numerous jobs, both direct (e.g., in construction and restoration) and indirect (in social services and NGO activities).

Finally, the reuse of these properties has had a strong impact on the restoration of the image of legality. The allocation of confiscated properties for social purposes sends a powerful message of resistance against crime and of returning property to the community, restoring the values of justice and legality within the territorial context. The transformation of these spaces into places for social and cultural support has strengthened the perception of legality as a foundational value of society.

Based on this clear framework of critical issues and benefits, it is possible to identify some improvement actions that can enhance the replicability of the model, as well as relevant important strategies:

Systematization among different interventions and social usage of confiscated buildings, including those located on different municipal territories, with cross-municipal planning approach.

This action requires interaction between social services management and the planning of interventions for confiscated housing within the different area plans of multiple municipalities to satisfy cross-municipal social needs.

Increasing the training level and skill qualifications of municipality stakeholders.

This action requires the planning of training actions for municipalities regarding the legislative framework related to the renovation of confiscated built assets, funding opportunities and modalities of participation in funding calls, management of the confiscated building reuse process, procedural framework to identify social needs, etc.

Increasing the visibility and social impacts of the legal return of confiscated buildings to the community and their reuse for social purposes.

This action requires the dissemination of social initiatives for the reuse of confiscated buildings reuse. Moreover, the definition of metrics and indicators for evaluating the social impact of the renovation and reuse of confiscated built assets on the specific territory is important. The development of metrics and indicators is also useful in supporting public administration in selecting projects eligible for public funding.

The activation of innovative models of public–private partnerships for the management of confiscated buildings.

This action requires the creation of a digital tool for synchronizing the “supply and demand” of services for social purposes between municipalities and the third sector or private entities. This digital tool could also be useful for sharing procedural aspects related to the renovation of confiscated assets and the best practices for the valorization of confiscated buildings.

4.2. The Mutual Benefits for Stakeholders of the Co-WIN Network

The experience gained from the pilot projects, which involved applying the Co-WIN model to confiscated buildings in the Lombardy region, allowed for the recognition of the specific advantages that stakeholders involved in the Co-WIN operational network obtain, and, in turn, offer to other operators in the same network (

Table 5).

The mutual benefits for all stakeholders of the Co-WIN network show the important role of public administration at the regional and municipal levels. They enable the availability of confiscated built assets for the opening of construction site schools, becoming promoters of the fight against organized crime through visible expressions of legality, actions against crime, and social support. Training institutions play a crucial role in the win–win network, providing technical and didactic expertise in training courses to support trainees at construction site schools and, in return, receiving the opportunity to experiment with innovative teaching models.

Construction companies—individually or through their associations—can receive manpower with technical–operational skills, providing a training opportunity to vulnerable people in construction site schools. Component manufacturers and material suppliers can offer construction materials and products to construction site schools, improving their environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) performance.

The third sector, comprising social services and third-sector associations, immigrant reception centers and employment support services, are essential for activating the Co-WIN model, as they identify vulnerable people who meet the eligibility requirements for the construction site school experience, and support them during their training and integration into the world of work.

In terms of enhancing the community’s social value, the Co-WIN network benefits vulnerable people by providing training and job opportunities, thereby helping them to increase their social inclusion and become the skilled manpower that is currently in high demand in the construction sector. In parallel, university students receive advanced training with “on-the-job” practice, contributing to the work of designers and construction managers throughout the construction process; moreover, the “reverse mentoring” processes between architecture students and operators of public administration can facilitate the use of innovative design tools and social networks or new platforms, which can achieve design identity and information sharing that enables to recognize the reuse of confiscated buildings, increasing their symbolic value of legality. Finally, the entire community benefits from the win–win network, as it receives legalized spaces, crime removal from the local area, and social services, while also providing proactive support for visible initiatives that promote legality.

4.3. The Social Relevance of the Co-WIN Model

The Co-WIN mode extends the benefits of reuse by intervening not only at the final use stage, but also by activating the social benefit for vulnerable people and providing many opportunities for different stakeholders. This starts from the construction phase of building renovation, increasing the value of the reuse process of confiscated built assets to the community.

The activation of construction site schools in the process of renovation of the confiscated buildings brings about the following social benefits:

Raising the awareness of students toward the social purposes of design and the principle of legality, which constitute two pivotal deontological foundations of the professions involved in the transformation processes of built environments;

Activating reverse mentoring practices (as a driver of digitization) through collaboration between students and practitioners in administrative offices and construction companies;

Providing vulnerable people with an opportunity for professional training and employment, thus an opportunity for social inclusion;

Providing opportunities for construction companies to train and educate their workers, who constitute the human capital of the construction sector;

The Co-WIN model also addresses the social issues of equity, legality, resource enhancement and capacity building.

Equity issues are pursued through the reduction of economic and social gaps caused by the economic and work dynamics of the construction sector. The technical–operational knowledge offered to vulnerable people can become a factor in enhancing their human and professional identity and dignity to gain advantage in social inclusion processes.

Legality issues are addressed by recognizing the strong symbolic value of returning confiscated buildings to the community. In addition, through construction site schools, vulnerable people are integrated into the regular labor market, keeping them away from potential recruitment by crime or illegal forms of work.

The valorization of resources is achieved by promoting the renovation and enhancement of the common good, as represented by the confiscated built assets, which are currently largely underutilized. In addition to the social value associated with the building’s use for social purposes (through allocation to the third sector), the Co-WIN model introduces a new value the anticipation of reuse for social purposes, which can be realized even during the construction phase. In addition, the activation of Co-WIN multi-stakeholder networks increases the visibility of the renovation and valorization of confiscated built assets, helping to find resources that guarantee the feasibility of building interventions and, raising their rate of assignment, thus increasing their, reuse for social purposes.

Enhancement of skills is possible through professional training of vulnerable people and the integration of construction operational aspects into university courses, utilizing innovative training methods and models. This integration can occur both through direct on-site practice (construction site school) and in the classroom (digital learning courses).

4.4. The Expected Social Impact Through the Replicability of the Co-WIN Model

The Co-WIN model’s social impact is assessed by the potential increase in the employability of vulnerable people trained in the worksite school.

The expected social impact is estimated based on the consistency of confiscated built assets, considering the replicability of the Co-WIN model at the national scale.

To estimate the social impact, the following assumptions are considered:

Buildings not assigned to the third sector are considered not yet renovated;

Construction site schools are activated in confiscated residential and commercial/industrial buildings, excluding confiscated land and garages;

Residential buildings, which constitute the largest amount of confiscated built assets, have an average area of 100 square meters;

In a typical construction site school in a confiscated building of 100 square meters, two vulnerable individuals (equal to 0.02 internships/square meter) and two students (equal to 0.02 internships/square meter) could be trained;

ANPAL (Agenzia Nazionale Politiche Attive Lavoro—National Agency for Active Employment Policies) data (updated to 2019) predict that approximately one-third of people trained through internship experiences will be employed; thus, it is possible to consider that 60% of vulnerable people trained in a construction site school can find employment.

Considering the size of the confiscated built asset (

Table 6), and considering the availability of 0.02 internships/square meter for vulnerable people, it is estimated that 192 vulnerable people could find employment in the Lombardy region and 2574 at the national level.

Thanks to third-sector actors’ engagement, several vulnerable people from the immigrant category were identified as potentially suitable for the internship experience at the Co-WIN construction site schools in the pilot projects.

Vulnerable people interested in the construction site school experience received basic training thanks to the training institutions in the Co-WIN network, gaining eligibility for access to construction sites.

However, vulnerable people have shown unwillingness to begin a training period with an extracurricular internship. In fact, in multiple cases, the selected vulnerable people voluntarily dropped out of the training during the construction site school experience.

This is a clear sign of a lack of education and social support. Vulnerable people often find themselves in precarious conditions, and with short periods of available residence permits, which prevents them from having a long-term vision of their future and understanding how training activities can help to enhance their value in finding employment opportunities and thus promote social inclusion.

Therefore, social service assistants should increase efforts in explaining to vulnerable people the value of training in enhancing their future, before introducing them to training courses such as the construction site schools.

Regarding the involvement of students in construction site schools, multiple internship experiences, for both first degree and master’s degree students, were available in the pilot projects. Students found a high level of satisfaction with the experience, with an evident enhancement of their knowledge.

5. Conclusions