The Application of a Social Identity Approach to Measure and Mechanise the Goals, Practices, and Outcomes of Social Sustainability

Abstract

1. Sustainable Development—Its Aspirations and Its Failings

2. An Emerging Need to Understand the Social Dimension of Sustainability

3. Social Capital and Its Role in Understanding Social Sustainability

4. The Social Identity Approach

5. A Social Identity Approach to Understanding Sustainability Outcomes

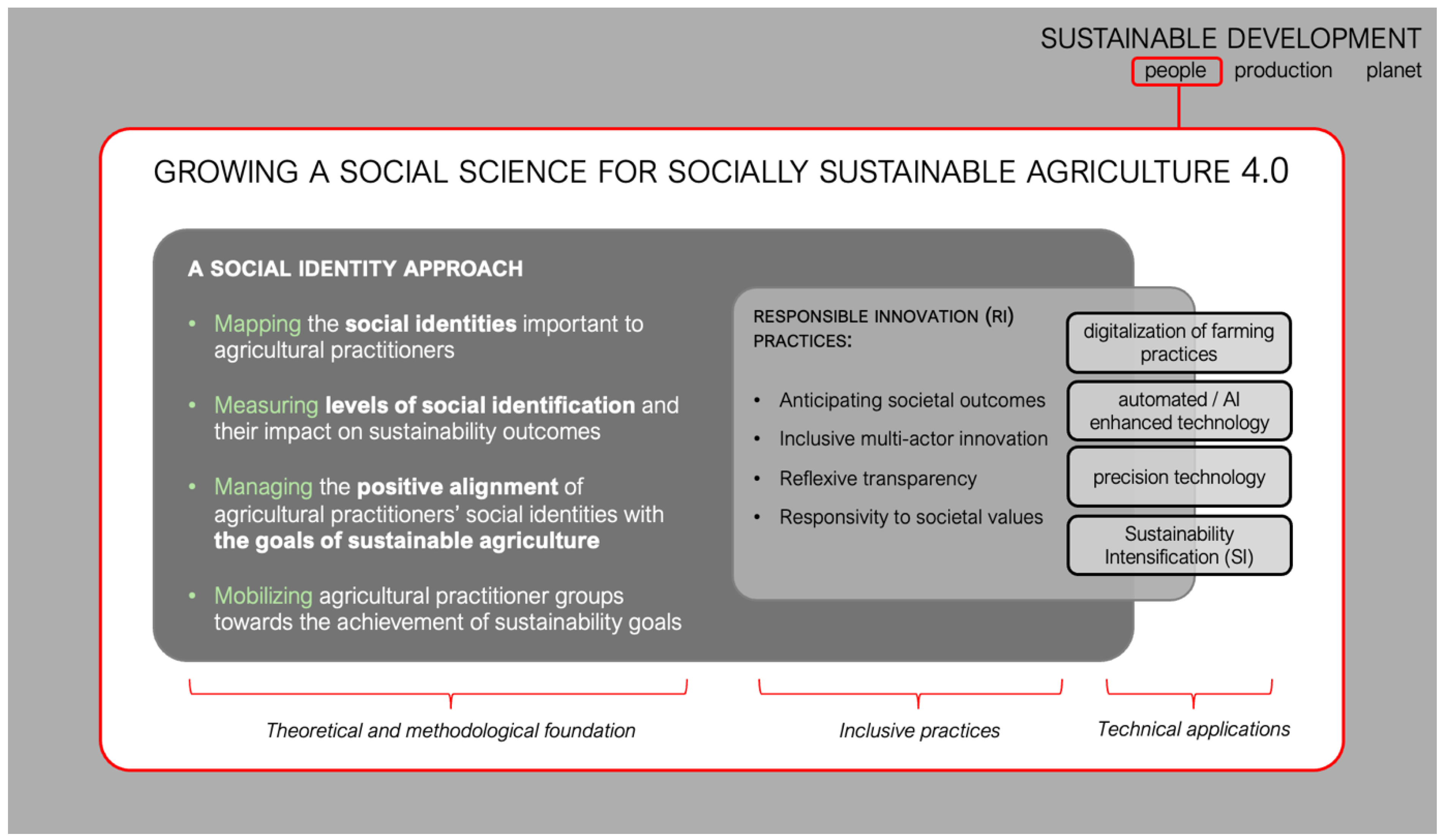

6. A Case Study: Delivering a Socially Sustainable Agriculture 4.0

7. Conclusions

“Whilst the benefits of transdisciplinary approaches are widely acknowledged, the integration of such approaches in conservation research and practice remains limited, underscoring a significant gap in current efforts to address global biodiversity and sustainability challenges”.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Seveso disaster, 1976; Love Canal disaster, 1978; Amoco Cadiz oil spill, 1978; Ok Tedi environmental disaster, 1984; Bhopal disaster, 1984; Chernobyl disaster, 1986; Hanford Nuclear, 1986; Exxon Valdez oil spill, 1989; Kuwait oil fires, 1991; Hickory Woods, 1998; Prestige oil spill, 2002; Prudhoe Bay oil spill, 2006; Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill, 2008; Deepwater Horizon oil spill, 2010; Fukishima Daiichi nuclear disaster, 2011; Oder environmental disaster, 2022; Ohio train derailment, 2023; Red Sea crisis, 2024. [see ‘Environmental disaster’ Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_disaster, accessed on 31 May 2025]. |

| 2 | Although some scholars have used the Kuznets Curve Hypothesis (Kuznets 1955) to suggest that economic growth is necessary to provide the means to remedy environmental damage, decades since this proposition was first made to the American Economic Association, there is little (if any) data to support it (Ruggerio 2021; Dinda 2004). |

References

- Agyeiwaah, Elizabeth, Prosper Bangwayo-Skeete, and Emmanuel Kwame Opoku. 2024. The impact of migrant workers’ inclusion on subjective well-being, organizational identification, and organizational citizenship behavior. Tourism Review 79: 250–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Inger. 2024. Emissions Gap Report 2024 Press Statement. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Araújo, Sara Oleiro, Ricardo Silva Peres, José Barata, Fernando Lidon, and José Cochicho Ramalho. 2021. Characterising the agriculture 4.0 landscape—Emerging trends, challenges and opportunities. Agronomy 11: 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, Mitja D., Stefan C. Schmukle, and Boris Egloff. 2009. Predicting actual behavior from the explicit and implicit self-concept of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97: 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Wayne E. 1990. Market networks and corporate behavior. American Journal of Sociology 96: 589–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycan, Tüzin, and Özge Öner. 2023. The dark side of social capital: A contextual perspective. The Annals of Regional Science 70: 779–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckerman, Wilfred. 1992. Economic growth and the environment: Whose growth? Whose environment? World Development 20: 481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Sarah V., Catherine Haslam, S. Alexander Haslam, Jolanda Jetten, Joel Larwood, and Crystal J. La Rue. 2022. GROUPS 2 CONNECT: An online activity to maintain social connection and well-being during COVID-19. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 14: 1189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Sarah V., Katharine H. Greenaway, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2017. Cognition in context: Social inclusion attenuates the psychological boundary between self and other. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 73: 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Sarah V., Katharine H Greenaway, S Alexander Haslam, Tegan Cruwys, Niklas K Steffens, Catherine Haslam, and Ben Cull. 2020. Social identity mapping online. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 118: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Sarah V., S. Alexander Haslam, Katharine H Greenaway, Tegan Cruwys, and Niklas K Steffens. 2023. A picture is worth a thousand words: Social identity mapping as a way of visualizing and assessing social group connections. In Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Identity in and Around Organizations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, Sarah Vivienne, Cara Stitzlein, and Simon Fielke. 2025. Sowing the seeds of sustainability change within organisations: The importance of working the ‘social’ soil. Sustainable Futures 9: 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, João Pedro, F. Ferreira, Antonio Dinis Marques, and Mafalda Nogueira. 2018. “Do as I say, not as I do”—A systematic literature review on the attitude-behaviour gap towards sustainable consumption of Generation Y. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 459: 012089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, Michael, and Henri Tajfel. 1973. Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 3: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, Christian, and Kim Mannemar Sønderskov. 2013. Is social capital a good concept? Social Indicators Research 114: 1225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenink, Marianne, and Olya Kudina. 2020. Values in responsible research and innovation: From entities to practices. Journal of Responsible Innovation 7: 450–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossel, Hartmut. 1999. Indicators for Sustainable Development: Theory, Method, Applications. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, Magnus. 2012. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 8: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2018. The forms of capital. In The Sociology of Economic Life. London: Routledge, pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, Robert H. W., Nicole D. Peterson, Poonam Arora, and Kevin Caldwell. 2016. Five approaches to social sustainability and an integrated way forward. Sustainability 8: 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscombe, Nyla R., and Daniel L. Wann. 1994. Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. European Journal of Social Psychology 24: 641–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 2013. Reducing prejudice through cross-categorization: Effects of multiple social identities. In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination. London: Psychology Press, pp. 165–83. [Google Scholar]

- Butalia, Radhika, Filip Boen, S. Alexander Haslam, Stef Van Puyenbroeck, Loes Meeussen, Pete Coffee, Nasrin Biglari, Mark W. Bruner, Aashritta Chaudhary, Paweł Chmura, and et al. 2025. The role of identity leadership in promoting athletes’ mental health: A cross-cultural study. Applied Psychology 74: e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassman, Kenneth G., and Patricio Grassini. 2020. A global perspective on sustainable intensification research. Nature Sustainability 3: 262–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champniss, Guy, Hugh N. Wilson, Emma K. Macdonald, and Radu Dimitriu. 2016. No I won’t, but yes we will: Driving sustainability-related donations through social identity effects. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 111: 317–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, Oliver, Rolf Van Dick, Ulrich Wagner, and Jost Stellmacher. 2003. When teachers go the extra mile: Foci of organisational identification as determinants of different forms of organisational citizenship behaviour among schoolteachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology 73: 329–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, Tristan. 2018. Criticisms of social capital theory: And lessons for improving practice. Social Capital Research 4: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, James S. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collict, Cameron, Alex J. Benson, Lee Schaefer, and Jeffrey G. Caron. 2025. Exploring how athletes navigate identity-related changes following sport-related concussion. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 14: 383–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Wesley E. 1992. William James’s theory of the self. The Monist 75: 504–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, Tegan, Catherine Haslam, Joanne A. Rathbone, Elyse Williams, S. Alexander Haslam, and Zoe C. Walter. 2022. Groups 4 Health versus cognitive–behavioural therapy for depression and loneliness in young people: Randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial with 12-month follow-up. The British Journal of Psychiatry 220: 140–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, Tegan, Niklas K. Steffens, S. Alexander Haslam, Catherine Haslam, Jolanda Jetten, and Genevieve A. Dingle. 2016. Social Identity Mapping: A procedure for visual representation and assessment of subjective multiple group memberships. British Journal of Social Psychology 55: 613–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, Matthieu, Anshu Vats, and Alvaro Biel. 2018. Agriculture 4.0: The Future of Farming Technology. Proceedings of the World Government Summit. Dubai: World Government Summit, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis, James. 2001. The myth of social capital in community development. Housing Policy Debate 12: 781–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, Nicola, Glen Bramley, Sinéad Power, and Caroline Brown. 2011. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development 19: 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rosnay, Joël. 1979. The Macroscope: A New World Scientific System. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Dinda, Soumyananda. 2004. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecological Economics 49: 431–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, Genevieve A., Rong Han, Kevin Huang, Sakinah S.J. Alhadad, Emma Beckman, Sarah V. Bentley, Shannon Edmed, Sjaan R. Gomersall, Leanne Hides, Nadine Lorimer, and et al. 2025. Sharper minds: Feasibility and effectiveness of a mental health promotion package for university students targeting multiple health and self-care behaviours. Journal of Affective Disorders 378: 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, Efrat, and Yosef Jabareen. 2017. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 9: 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engbers, Trent A., Michael F. Thompson, and Timothy F. Slaper. 2017. Theory and measurement in social capital research. Social Indicators Research 132: 537–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Seymour. 1973. The self-concept revisited: Or a theory of a theory. American Psychologist 28: 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, Malin, Ailiana Santosa, Liv Zetterberg, Ichiro Kawachi, and Nawi Ng. 2021. Social capital and sustainable social development—How are changes in neighbourhood social capital associated with neighbourhood sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics? Sustainability 13: 13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, Ian, and Sue Kilpatrick. 2000. What is social capital? A study of interaction in a rural community. Sociologia Ruralis 40: 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Ben. 2010. Theories of Social Capital: Researchers Behaving Badly. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigos-Simon, Fernando J., M. Dolores Botella-Carrubi, and Tomas F. Gonzalez-Cruz. 2018. Social capital, human capital, and sustainability: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Sustainability 10: 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, Frank W. 2019. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 39: 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, Frank W., Andrew McMeekin, and Benjamin Pfluger. 2020. Socio-technical scenarios as a methodological tool to explore social and political feasibility in low-carbon transitions: Bridging computer models and the multi-level perspective in UK electricity generation (2010–2050). Technological Forecasting and Social Change 151: 119258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleibs, Ilka H. 2025. A social identity approach to crisis leadership. British Journal of Social Psychology 64: e12805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, Anthony G., Mahzarin R Banaji, Laurie A. Rudman, Shelly D. Farnham, Brian A. Nosek, and Deborah S. Mellott. 2002. A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review 109: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grybauskas, Andrius, Alessandro Stefanini, and Morteza Ghobakhloo. 2022. Social sustainability in the age of digitalization: A systematic literature Review on the social implications of industry 4.0. Technology in Society 70: 101997. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, Catherine, Jolanda Jetten, Tegan Cruwys, Genevieve A. Dingle, S. Alexander Haslam, and Lynsey Mahmood. 2018. The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, Catherine, S. Alexander Haslam, Jolanda Jetten, Tegan Cruwys, and Niklas K. Steffens. 2021. Life change, social identity, and health. Annual Review of Psychology 72: 635–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, Catherine, Tegan Cruwys, Melissa X.-L. Chang, Sarah V. Bentley, S. Alexander Haslam, Genevieve A. Dingle, and Jolanda Jetten. 2019. GROUPS 4 HEALTH reduces loneliness and social anxiety in adults with psychological distress: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 87: 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S. Alexander. 2017. The social identity approach to education and learning. In Self and Social Identity in Educational Contexts. Abingdon: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, S. Alexander, John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, Craig McGarty, and Brett K. Hayes. 1992. Context-dependent variation in social stereotyping 1: The effects of intergroup relations as mediated by social change and frame of reference. European Journal of Social Psychology 22: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S. Alexander, Jolanda Jetten, Mazlan Maskor, Blake McMillan, Sarah V. Bentley, Niklas K. Steffens, and Susan Johnston. 2022. Developing high-reliability organisations: A social identity model. Safety Science 153: 105814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, Bill, Mary Mellor, and Geoff O'BRien. 2005. Sustainable development: Mapping different approaches. Sustainable Development 13: 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, Matthew J. 2008. Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2: 204–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irene, Julius Omokhudu, Chux Daniels, Bridget Nneka Obiageli Irene, Mary Kelly, and Regina Frank. 2024. A social identity approach to understanding sustainability and environmental behaviours in South Africa. Local Environment, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakku, Emma, Aysha Fleming, Martin Espig, Simon Fielke, Susanna Finlay-Smits, and James Alan Turner. 2023. Disruption disrupted? Reflecting on the relationship between responsible innovation and digital agriculture research and development at multiple levels in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Agricultural Systems 204: 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, Jolanda, Catherine Haslam, S. Alexander Haslam, Genevieve Dingle, and Janelle M. Jones. 2014. How groups affect our health and well-being: The path from theory to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review 8: 103–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, Jolanda, Nyla R. Branscombe, S. Alexander Haslam, Catherine Haslam, Tegan Cruwys, Janelle M. Jones, Lijuan Cui, Genevieve Dingle, James Liu, Sean Murphy, and et al. 2015. Having a lot of a good thing: Multiple important group memberships as a source of self-esteem. PLoS ONE 10: e0124609. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, Laurens, Emma Jakku, and Pierre Labarthe. 2019. A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 90: 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, Sally, Kïrsten A. Way, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2025. ‘Whatever your job is, we are all about doing that thing super well’: High-reliability followership as a key component of operational success in elite air force teams. British Journal of Social Psychology 64: e12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, Emiko. 2012. Social capital networks for achieving sustainable development. Local Environment 17: 1043–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, Simon. 1955. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. American Economic Review 65: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lah, Oliver. 2025. Breaking the silos: Integrated approaches to foster sustainable development and climate action. Sustainable Earth Reviews 8: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasi, Heiner, Peter Fettke, Hans-Georg Kemper, Thomas Feld, and Michael Hoffmann. 2014. Industry 4.0. Business & Information Systems Engineering 6: 239–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Hao, Junchi Liu, and Wei-Yew Chang. 2024. Influence of Self-Identity and Social Identity on Farmers’ Willingness for Cultivated Land Quality Protection. Land 13: 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Fei, and Meng Qi. 2022. Enhancing organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: Integrating social identity and social exchange perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 15: 1901–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsky, Neil. 1995. When is “obedience” obedience? Conceptual and historical commentary. Journal of Social Issues 51: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Herbert W., and Andrew J. Martin. 2011. Academic self-concept and academic achievement: Relations and causal ordering. British Journal of Educational Psychology 81: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, Francesc-Xavier, and Josep M. Sole-Sedeno. 2023. Social sustainability, social capital, health, and the building of cultural capital around the Mediterranean diet. Sustainability 15: 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, Stanley. 1963. Behavioral study of obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67: 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, Stanley, and C. Gudehus. 1974. Obedience to Authority. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Arthur G. 1995. Constructions of the obedience experiments: A focus upon domains of relevance. Journal of Social Issues 51: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, Penelope J. 1987. The salience of social categories. In Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 117–41. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, Penelope J., John C. Turner, and S. Alexander Haslam. 1991. Perceiving people as group members: The role of fit in the salience of social categorizations. British Journal of Social Psychology 30: 125–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisto, Larry. 1999. The business of sustainability. Ecological Economics 29: 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, Richard, Jack Stilgoe, Phil Macnaghten, Mike Gorman, Erik Fisher, Dave Guston, and John Bessant. 2013a. A framework for responsible innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, Richard, Phil Macnaghten, and Jack Stilgoe. 2020. Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. In Emerging Technologies. London: Routledge, pp. 117–26. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, Richard J., John R. Bessant, and Maggy Heintz. 2013b. Responsible Innovation. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library, vol. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Hyun Jung, and Li Min Lin. 2020. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. Journal of Business Research 117: 623–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platow, Michael, Maria Durante, Naeidra Williams, Matthew Garrett, Jarrod Walshe, Steven Cincotta, George Lianos, and Ayla Barutchu. 1999. The contribution of sport fan social identity to the production of prosocial behavior. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 3: 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social capital: It’s origins and applications in contemporary society. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, Tom, and Russell Spears. 1998. Deindividuation and antinormative behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 123: 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, Tom, Lenka J. Wichmann, Anne M. van Valkengoed, and Hanneke van der Hoef. 2019. Social identification and depression: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology 49: 110–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, Tom, S Alexander Haslam, and Lise Jans. 2013. A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, Jules N. 1997. The sustainable intensification of agriculture. Natural Resources Forum 21: 247–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 1994. Social capital and public affairs. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 47: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, Stephen D., Russell Spears, and Tom Postmes. 1995. A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. European Review of Social Psychology 6: 161–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, Stephen D., S. Alexander Haslam, and Joanne R Smith. 2012. Working toward the experimenter: Reconceptualizing obedience within the Milgram paradigm as identification-based followership. Perspectives on Psychological Science 7: 315–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Katherine J., S. Alexander Haslam, and John C. Turner. 2012. Prejudice, social identity and social change: Resolving the Allportian problematic. In Beyond Prejudice: Extending the Social Psychology of Conflict, Inequality and Social Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, David Christian, Rebecca Wheeler, Michael Winter, Matt Lobley, and Charlotte-Anne Chivers. 2021. Agriculture 4.0: Making it work for people, production, and the planet. Land Use Policy 100: 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, Carlos Alberto. 2021. Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. Science of the Total Environment 786: 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim. 1999. ‘Earth system’ analysis and the second Copernican revolution. Nature 402 Suppl. S6761: C19–C23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaiser, Viktoria, Shyam Ranganathan, Ranjula Bali Swain, and David J. T. Sumpter. 2017. The sustainable development oxymoron: Quantifying and modelling the incompatibility of sustainable development goals. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 24: 457–70. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens, Niklas K., S. Alexander Haslam, Sebastian C. Schuh, Jolanda Jetten, and Rolf van Dick. 2017. A meta-analytic review of social identification and health in organizational contexts. Personality and Social Psychology Review 21: 303–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, Niklas K., S. Alexander Haslam, Stephen D. Reicher, Michael J. Platow, Katrien Fransen, Jie Yang, Michelle K. Ryan, Jolanda Jetten, Kim Peters, Filip Boen, and et al. 2014. Leadership as social identity management: Introducing the Identity Leadership Inventory (ILI) to assess and validate a four-dimensional model. The Leadership Quarterly 25: 1001–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, Jack, Richard Owen, and Phil Macnaghten. 2020. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. In The Ethics of Nanotechnology, Geoengineering, and Clean Energy. London: Routledge, pp. 347–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Wendy, and Jody Hughes. 2002. Social Capital: Empirical Meaning and Measurement Validity. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, Michael G. Billig, Robert P. Bundy, and Claude Flament. 1971. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 1: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, John C., Michael A. Hogg, Penelope J. Oakes, Stephen D. Reicher, and Margaret S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-98657-000 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Twomey, Alice J., Jayden Hyman, Karlina Indraswari, Maximilian Kotz, Courtney L. Morgans, and Kevin R. Bairos-Novak. 2025. From silos to solutions: Navigating transdisciplinary conservation research for early career researchers. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 23: 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UKRI. 2025. A Brief History of Climate Change Discoveries. Swindon: UK Research and Innovation. Available online: https://www.discover.ukri.org/a-brief-history-of-climate-change-discoveries/index.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- UNFCCC Secretariat. 2025. Key Aspects of the Paris Agreement. Bonn: United Nations Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 1987. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. UN. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- United Nations. 2025. Conference of the Parties (COP). Bonn: United Nations Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- University of Cambridge. 2025. What Is COP? Cambridge: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL). [Google Scholar]

- Valera, Sergi, and Joan Guàrdia. 2002. Urban social identity and sustainability: Barcelona’s Olympic Village. Environment and Behavior 34: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, Jeroen CJM. 1996. Ecological Economics and Sustainable Development: Theory, Methods and Applications. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dick, Rolf, Michael W. Grojean, Oliver Christ, and Jan Wieseke. 2006. Identity and the extra mile: Relationships between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behaviour. British Journal of Management 17: 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, Julia M., Tessa de Geus, Bonno Pel, Flor Avelino, Sabine Hielscher, Thomas Hoppe, Susan Mühlemeier, Agata Stasik, Sem Oxenaar, Karoline S. Rogge, and et al. 2020. Beyond instrumentalism: Broadening the understanding of social innovation in socio-technical energy systems. Energy Research & Social Science 70: 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne-Jones, Sophie, John Hyland, Prysor Williams, and Dave Chadwick. 2020. Collaboration for sustainable intensification: The underpinning role of social sustainability. Sociologia Ruralis 60: 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Xiaohong, Zheng Zhou, Fu Yang, and Huijie Qi. 2021. Embracing responsible leadership and enhancing organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A social identity perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 632629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Tarli, Jennifer A. Hunter, Sarah V. Bentley, Prudence Millear, S. Alexander Haslam, and Catherine Haslam. 2025. A Social Identity Intervention to Improve Mental Health in Construction Workers. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 151: 4025072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, Philip G. 1969. The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 17: 237–307. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bentley, S.V. The Application of a Social Identity Approach to Measure and Mechanise the Goals, Practices, and Outcomes of Social Sustainability. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080480

Bentley SV. The Application of a Social Identity Approach to Measure and Mechanise the Goals, Practices, and Outcomes of Social Sustainability. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080480

Chicago/Turabian StyleBentley, Sarah Vivienne. 2025. "The Application of a Social Identity Approach to Measure and Mechanise the Goals, Practices, and Outcomes of Social Sustainability" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080480

APA StyleBentley, S. V. (2025). The Application of a Social Identity Approach to Measure and Mechanise the Goals, Practices, and Outcomes of Social Sustainability. Social Sciences, 14(8), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080480