Social Innovation and Social Care: Local Solutions to Global Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

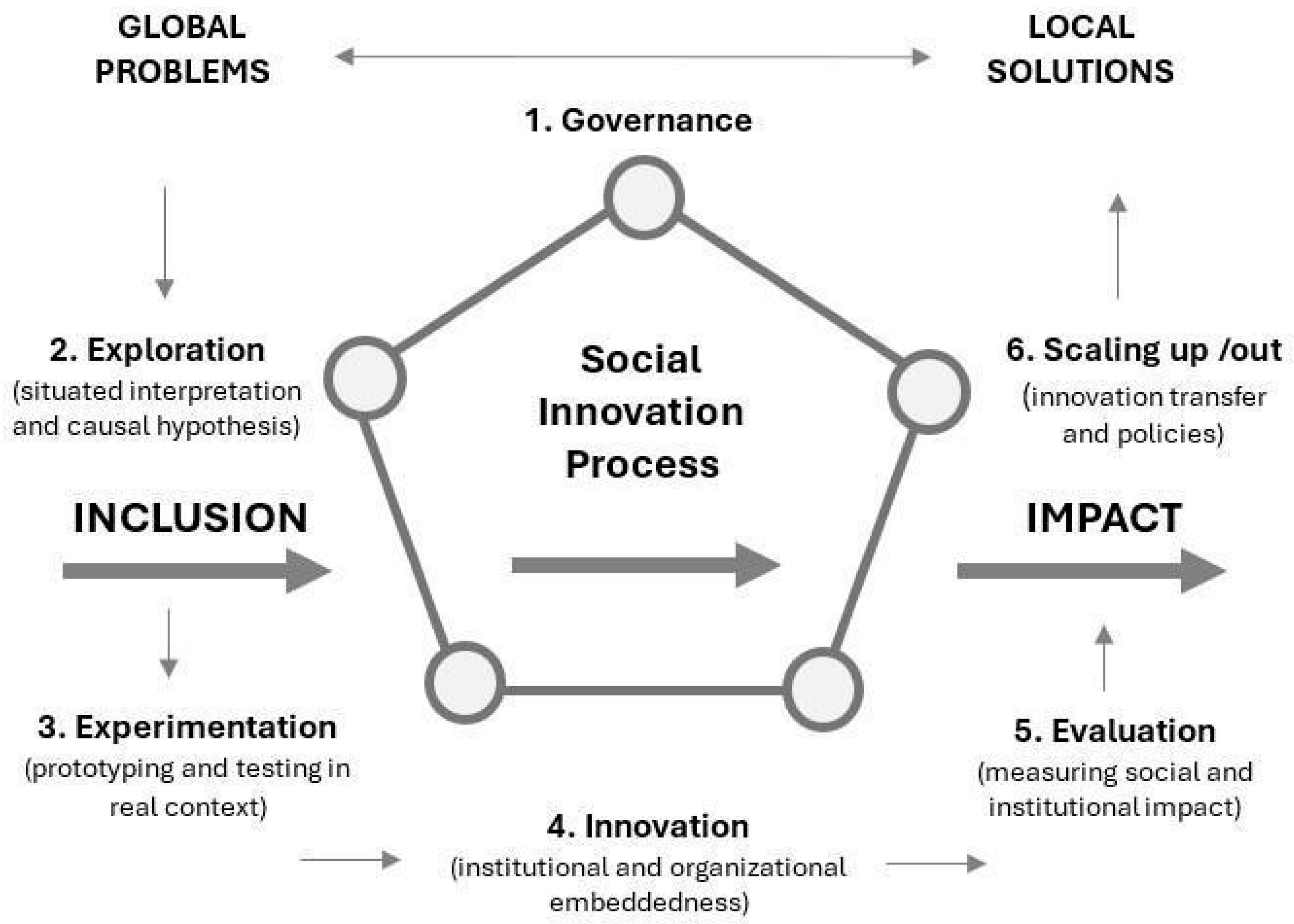

2. Social Innovation Process: From Global Problems to Local Solutions

3. Global Problems: Aging and Longevity

3.1. Longevity and Population: Trends

3.2. Challenges for Health and Social Services

3.3. Summarizing the Challenges

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Case Selection

4.3. Research Questions and Objectives

- What is the internal logic and theory of change underpinning the implementation of the Local Care Ecosystems model?

- What strengths and limitations emerge from the implementation of the model in relation to its potential for replication and transfer?

- Based on these questions, the study aims to:

- Reconstruct and systematize the internal logic of the Local Care Ecosystems model, identifying its key components, phases, and implementation dynamics.

4.4. Limitations

- Limitations in data availability and digital competencies. The Interoperable Data Platform (Zaintza Datu Gunea) is a relevant initiative within the Local Care Ecosystems that enables service coordination for personalization. However, disaggregated and systematized data on the older adults served, profiles of frailty and dependency, and the distribution of support among services and actors are still not available for integration into the Platform. Another significant limitation concerns the technological capacities of public services and territorial entities within the ecosystem, which restricts the ability to achieve data interoperability. Limited digital skills among users/beneficiaries and certain professional profiles also represent a noteworthy constraint.

- Mismatch between administrative and social timeframes. Experimental projects require extended timeframes to consolidate the organizational, cultural, and relational changes they entail. However, the funding timelines for projects and the associated administrative requirements can limit experimental processes. This mismatch between administrative schedules and the temporality of social transformation processes may affect the impact of innovation initiatives.

- Uneven maturity levels of the ecosystems. Local Care Ecosystems exhibit varying degrees of development, depending on local capacities. While some territories have advanced in consolidating complex coordination and evaluation structures, others remain in early stages of reflection or exploration. This disparity presents significant challenges for both scaling and the generation of collective and transferable learning.

5. Results

5.1. Local Care Ecosystem as Local Solutions

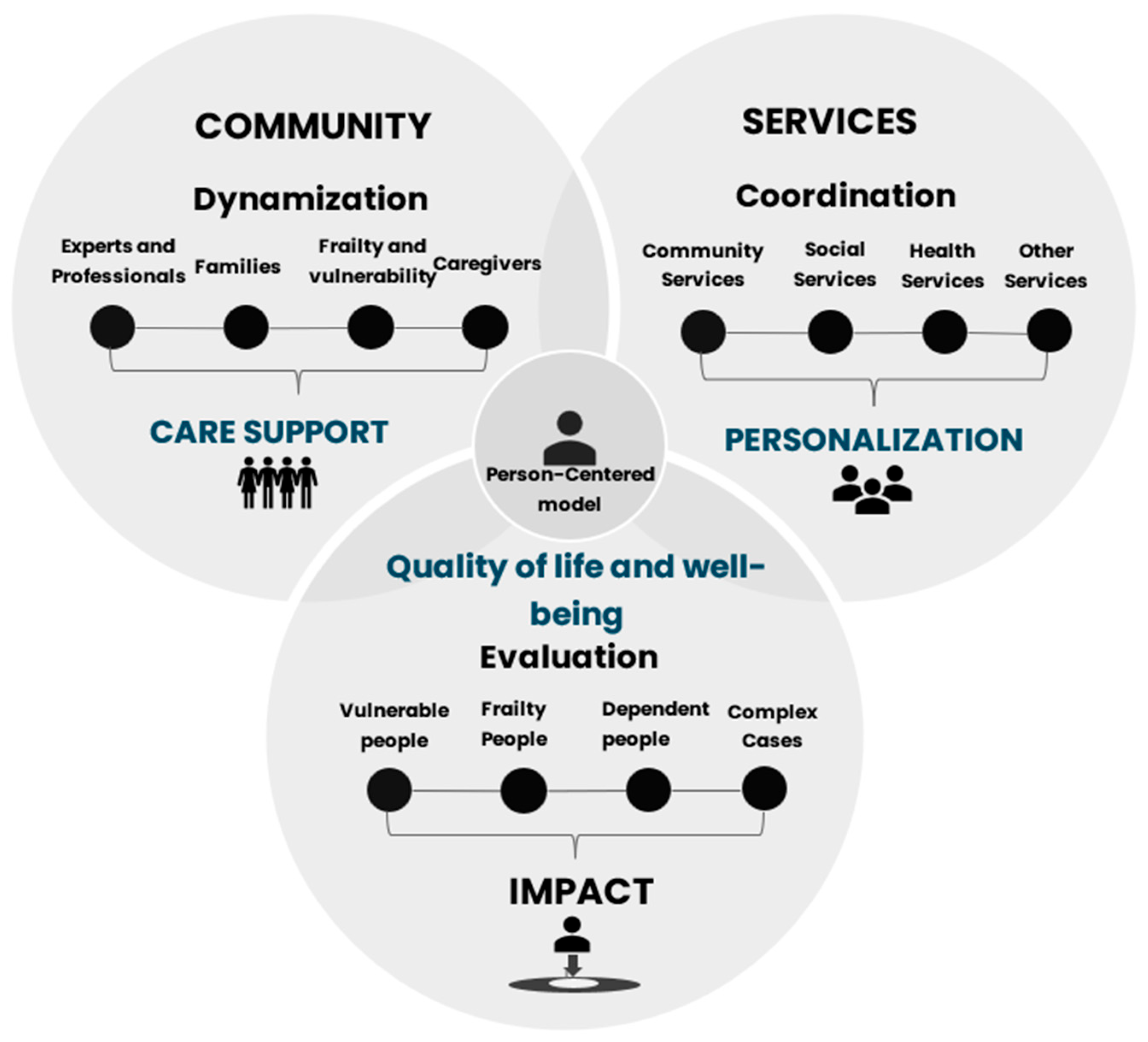

5.2. Local Care Ecosystems: An Integrated Model

- Objective 1. SERVICES. Improve the coordination of social services, health services, community services, and other services to provide person-centered care and ensure continuity of care.

- Objective 2. COMMUNITY. Foster relationships among frail and dependent individuals, experts, professionals, families, and caregivers by consolidating local support networks and proximity networks.

- Objective 3. IMPACT. Promote models for monitoring and evaluating the quality of life and well-being of vulnerable, frail, and dependent individuals, as well as those considered complex cases.

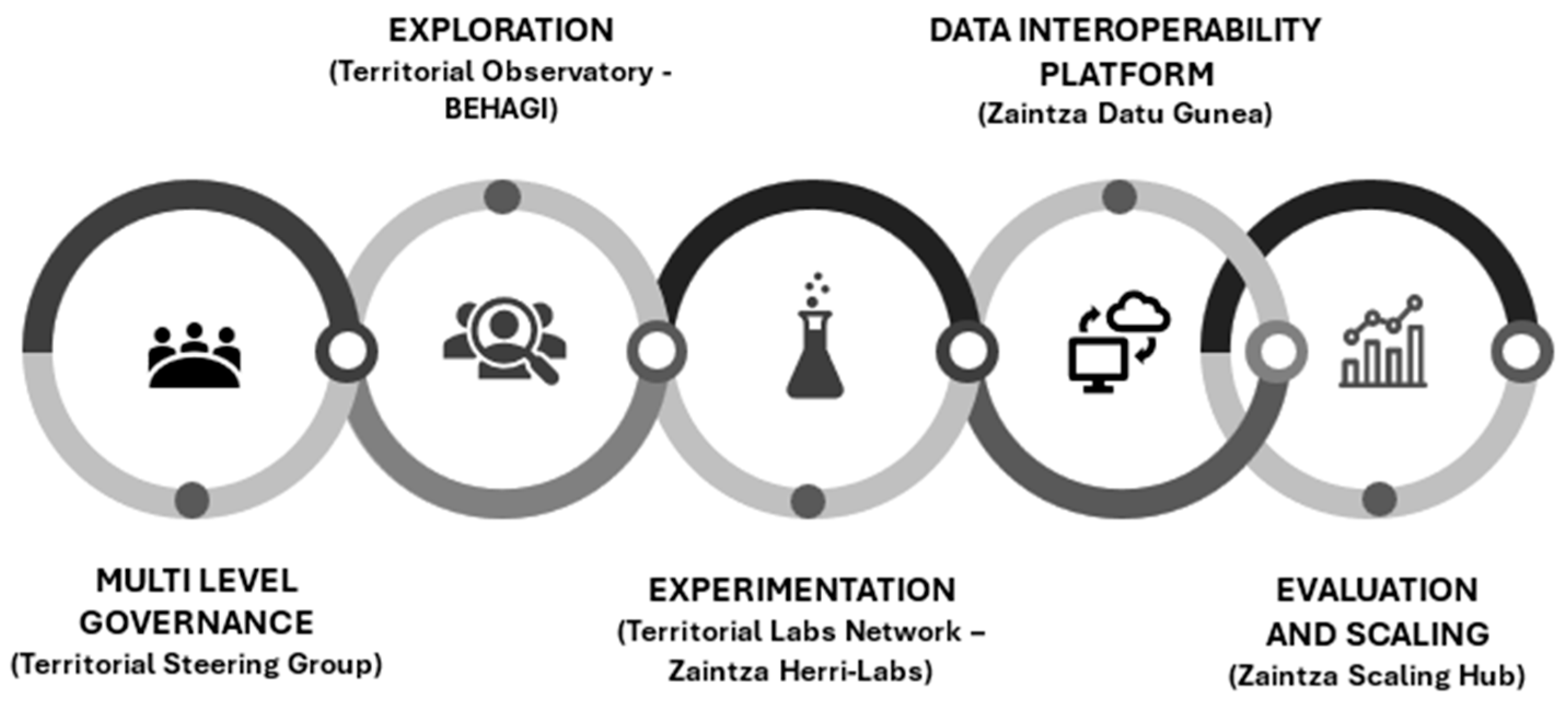

- Governance. Multilevel governance is organized through a Steering Group at the territorial level, composed of health services, health-social services, and social services, with working groups of professionals and experts, as well as panels of users/beneficiaries of social services. The main function of governance is to activate and organize spaces for cooperation between different institutional levels and types of local stakeholders (public, private, and social), as well as spaces for the participation of users, families, and professionals to deploy the Local Care Ecosystem (exploratory, experimental, stabilization, and scaling phases). At the level of each ecosystem, these tasks are carried out by a management unit (see Figure 3).

- Exploration. Exploration within LCE aims to develop local diagnostics that interpret the global trends and challenges of aging and longevity, translating these into local conditions. This involves applying methodologies such as problem mapping, solution mapping, frailty and dependency mapping, local capacity mapping, trend analysis, and participatory future design regarding aging and longevity. These tasks are performed by each ecosystem in collaboration with the Territorial Observatory (BEHAGI/SIA-ADINBERRI).

- Experimentation. Experimentation in LCE involves implementing experimental projects that test new or improved products, processes, methods, and/or services to promote personalized care, service coordination, and community-based care, with the goal of improving the quality of life of frail and dependent individuals living at home. These tasks are coordinated by a Territorial Laboratory (Zaintza Herri Lab), which also supports the monitoring and evaluation of experimental projects developed at the local level.

- Digitalization. Digitalization in LCE focuses on deploying the Interoperable Data Platform (Zaintza Datu Gunea) for social and health data, connecting the management of public service data with local stakeholders (third sector organizations, companies, universities), and with users/beneficiaries of social services. This facilitates personalized care management and system coordination. The outcome of this phase is improved integration of social and health data for local-level services (see Figure 3).

- Evaluation and Scaling up/out. Monitoring within LCE measures the progress in personalized care, service coordination, and the promotion of community-based care. Evaluation assesses the social impact (improvement in the quality of life and well-being of frail and dependent individuals) and includes cost-effectiveness analyses to determine the sustainability of the ecosystems. These monitoring and evaluation processes are conducted in the territorial scaling laboratory (Zaintza Scaling Hub) (see Figure 3).

- Institutional consolidation and coordination figure. Over the five years of development, governance structures (steering committees) have been consolidated, as well as forms of participation for professionals, users/beneficiaries, and families in the deployment of the ecosystems. When municipalities establish a Management Unit, the ecosystems are more successful in energizing projects and ensuring their continuity, facilitating dialogue with the various actors and sectors involved.

- Multidimensional innovation. Most experimental projects have incorporated the three fundamental axes of the LCE model: personalization of care, improvement of service quality and coordination, and strengthening of community care. Some projects, due to their early stage or focus on specific services such as Home Help Service (SAD), have progressed unevenly across these three axes, but the overall trend is positive.

- Transferability and local adaptation. The experiences developed have demonstrated a high degree of transferability. However, it is not possible to directly replicate all projects and their results; rather, an adaptation process is required for each ecosystem, given that each municipality has specific organizational structures, community networks, and institutional cultures.

- Consolidation and sustainability. Half of the Local Care Ecosystems foresee progressive expansion, while the other half remain in exploration and experimentation phases. Sustainability depends not only on financial resources but also on the consolidation of local governance, strengthening of local capacities, and the establishment of appropriate regulatory and organizational frameworks aligned with an ecosystem-based approach to care.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

- Complex cases. One of the observed global problems relates to increased life expectancy, a trend associated with a greater number of years and a higher prevalence of chronic diseases. Local Care Ecosystems promote service coordination processes to provide personalized management for complex cases.

- Service coordination. Fragmentation in long-term care services is a global issue that requires local solutions. LCE foster the coordination of social, health, health-social, and community services, offering higher-quality care strategies by providing a continuum of care.

- Community approach. In response to a marked global trend of changing family structures—one of the pillars of the care model—older adults are increasingly experiencing loneliness. Local Care Ecosystems consolidate community support networks, where older adults can take active roles in their care networks, not just recipients of care, thereby addressing the problem of unwanted loneliness.

- Centrality of autonomy. In contrast to the global trend where aging calls for models that allow older adults to maintain their autonomy—prioritizing staying in their own homes and personalizing support systems—Local Care Ecosystems aim to create technological, organizational, and relational solutions that promote independent living and active participation in the community.

- Personalization. The personalization of care is a global trend that requires promoting solutions tailored to the characteristics, resources, and culture of each individual. LCE design personalized plans and services, integrating technological tools to adjust support to each person and their environment, thereby enhancing personalization.

- Collaborative and Multi-Actor Governance. The creation of social innovation ecosystems depends on collaboration among the public sector, private sector, and civil society, generating multi-actor platforms and social experimentation spaces (“social sandboxes”) that allow for the testing and adaptation of new solutions prior to scaling. This shared governance facilitates sustainability, knowledge transfer, and the continuous adaptation of care models, guided by personalization, coordination, and community-based care.

- Innovation as a Driver of Sustainability and Equity. Demographic pressure and the growing demand for care require sustainable and equitable models, in which social and technological innovation enable the optimization of resources and guarantee the universality and quality of care. Local Care Ecosystems integrate resources, develop public-private-social partnerships, and conduct cost-effectiveness evaluations to foster public innovations that reinforce the long-term viability of Local Care Ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alonso González, David, Melisa Campana Alabarce, and Antonio López Peláez. 2024. La agenda de la innovación social en Trabajo Social: Propuestas y retos. In Tratado General de Trabajo Social, Servicios Sociales y Política Social. Edited by Jorge Garcés Ferrer. Valencia: Tirant Humanidades, vol. 1, pp. 545–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, Christopher, and Jacob Torfing, eds. 2014. Public Innovation Through Collaboration and Design. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Antadze, Nino, and Frances R. Westley. 2012. Impact Metrics for Social Innovation: Barriers or Bridges to Radical Change? Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 3: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Astray, Andrés, David Alonso González, and Melisa Campana Alabarce. 2023. Innovación social oculta en Servicios Sociales: Periferias y disrupciones. In Los Servicios Sociales ante el reto de la innovación: Participación, tecnologías e investigación. Edited by Manuela Angela Fernández Borrero and Octavio Vázquez Aguado. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, Flor, Julia M. Wittmayer, Bonno Pel, Paul Weaver, Adina Dumitru, Alex Haxeltine, René Kemp, Michael S. Jørgensen, Tom Bauler, Saskia Ruijsink, and et al. 2019. Transformative Social Innovation and (Dis)empowerment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 145: 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Susan C., and Abid Mehmood. 2015. Social innovation and the governance of sustainable places. Local Environment 20: 321–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, Christine M., Jovanna Rosen, Jeimee Estrada-Miller, and Gary D. Painter. 2023. The Social Innovation Trap: Critical Insights into an Emerging Field. Academy of Management Annals 17: 684–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, Dan. 2020. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults—A mental health/public health challenge. JAMA Psychiatry 77: 990–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, David E., David Canning, and Alyssa Lubet. 2015. Global population aging: Facts, challenges, solutions and perspectives. Daedalus 144: 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borins, Sandford. 2001. Public Management Innovation: Toward a Global Perspective. The American Review of Public Administration 31: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, John M., Michael Quinn Patton, and Ruth A. Bowman. 2011. Working with Evaluation Stakeholders: A Rationale, Step-Wise Approach and Toolkit. Evaluation and Program Planning 34: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campomori, Francesca, and Mattia Casula. 2022. How to Frame the Governance Dimension of Social Innovation: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Evidence. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 36: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Spila, Javier. 2018. Social Innovation Excubator developing transformational work-based learning in the Relational University. Higher Education, Skills and Work-based Learning 8: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Spila, Javier, and David Alonso González. 2021. Social Innovation Patents. Journal of Social Work Education and Practice 6: 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Spila, Javier, Álvaro Luna, and Alfonso Unceta. 2016. Social Innovation Regimes: An Exploratory Framework to Measure Social Innovation. SIMPACT Working Paper 2016 (1). Gelsenkirchen: Institute for Work and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Chataway, Joanna, Richard Hanlin, and Raphael Kaplinsky. 2014. Inclusive innovation: An architecture for policy development. Innovation and Development 4: 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessers, Ezra, and Bernard J. Mohr. 2020. An ecosystem perspective on care coordination: Lessons from the field. International Journal of Care Coordination 23: 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Ding, Robert Eres, and Daniel L. Surkalim. 2022. A lonely planet: Time to tackle loneliness as a public health issue. BMJ 377: o1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, Sharon A. M., Wouter P. L. van Galen, Bob Walrave, Elke den Ouden, Rianne Valkenburg, and Georges Romme. 2023. A Dynamic Perspective on Collaborative Innovation for Smart City Development: The Role of Uncertainty, Governance, and Institutional Logics. Organization Studies 44: 1679–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, Nicola J., and Dan Blazer. 2020. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a National Academies report. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 28: 1233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards-Schachter, Mónica, and Matthew L. Wallace. 2017. Shaken, but not stirred: Sixty years of defining social innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 119: 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. 2022. Scaling-Up Social Innovation: Seven Steps for Using ESF + ESF. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2024. EU Life Expectancy Estimated at 81.5 Years in 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240503-2 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Eusko Jaurlaritza-Gobierno Vasco. 2023. Estrategia Vasca con las Personas Mayores, 2021–2024. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Departamento de Igualdad, Justicia y Políticas Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, Adalbert, and Benjamin Ewert. 2015. Social Innovation for Social Cohesion: Transnational Patterns and Approaches from 20 European Cities. Leipzig: EENC Report. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, John, Jan Rotmans, and Johan Schot. 2010. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haxeltine, Alexander, Bonno Pel, Adina Dumitru, Flor Avelino, René Kemp, and Julia M. Wittmayer. 2017. Building a Middle-Range Theory of Transformative Social Innovation: Theoretical Pitfalls and Methodological Responses. European Public & Social Innovation Review 2: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Padilla, José Manuel, María Dolores Ruiz-Fernández, José Granero-Molina, Rocío Ortiz-Amo, María Mar López-Rodríguez, and Cayetano Fernández-Sola. 2021. Perceived health, caregiver overload and perceived social support in family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s: Gender differences. Health & Social Care in the Community 29: 1001–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzebski, Marcin Pawel, Thomas Elmqvist, Alexandros Gasparatos, Kensuke Fukushi, Sofie Eckersten, Dagmar Haase, Julie Goodness, Sara Khoshkar, Osamu Saito, Kazuhiko Takeuchi, and et al. 2021. Ageing and population shrinking: Implications for sustainability in the urban century. npj Urban Sustainability 1: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, Bob, Frank Moulaert, Lars Hulgård, and Abdelillah Hamdouch. 2013. Social Innovation Research: A New Stage in Innovation Analysis? In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research. Edited by Frank Moulaert, Diana MacCallum, Abid Mehmood and Abdelillah Hamdouch. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 110–30. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Hafiz Tahir A., Kwame M. Addo, and Helen Findlay. 2024. Public health challenges and responses to the growing ageing populations. Public Health Challenges 3: e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Ellen E., Colin Depp, Barton W. Palmer, Danielle Glorioso, Rebecca Daly, Jinyuan Liu, Xin M. Tu, Ho-Cheol Kim, Peri Tarr, Yasunori Yamada, and et al. 2019. High prevalence and adverse health effects of loneliness in community-dwelling adults across the lifespan: Role of wisdom as a protective factor. International Psychogeriatrics 31: 1447–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legarreta-Iza, Matxalen, Elena Martínez-Tola, Unai Villena-Camarero, and Amaia Altuzarra-Artola. 2024. Evaluación del programa Pasaia Zaintza HerriLab para el desarrollo de un ecosistema local de cuidados en el municipio de Pasaia (Gipuzkoa). Zerbitzuan: Revista de Servicios Sociales 83: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönngren, Johanna, and Katrien van Poeck. 2021. Wicked problems: A mapping review of the literature. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 28: 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Wendy, Meghan Ambrens, and Melanie Ohl. 2019. Enhancing resilience in community-dwelling older adults: A rapid review of the evidence and implications for public health practitioners. Frontiers in Public Health 7: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Michele-Lee, Darcy Riddell, and Dana Vocisano. 2015. Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep: Strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 2015: 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlett Paredes, Alejandra, Ellen E. Lee, Lisa Chik, Saumya Gupta, Barton W. Palmer, and Lawrence A. Palinkas. 2021. Qualitative study of loneliness in a senior housing community: The importance of wisdom and other coping strategies. Aging & Mental Health 25: 559–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, Francesco, and Abid Mehmood. 2010. Spaces of social innovation. In Handbook of Local and Regional Development. Edited by Andy Pike, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and John Tomaney. London: Routledge, pp. 212–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, Geoff, Simon Tucker, Rushanara Ali, and Ben Sanders. 2007. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated. London: The Young Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, Alex, and James Gregory Dees. 2015. Social innovation. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition. Edited by James D. Wright. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 355–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, Alex, Julie Simon, and Madeleine Gabriel, eds. 2015. New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2011. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pue, Kristen, Christian Vandergeest, and Dan Breznitz. 2016. Toward a Theory of Social Innovation. Innovation Policy Lab White Paper No. 2016-01. Toronto: University of Toronto, Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Gonçalves, José Alberto, Pedro A. Costa, and Inês Leal. 2023. Loneliness, ageism, and mental health: The buffering role of resilience in seniors. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 23: 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Marco, Jarmo Vakkuri, and Jan-Erik Johanson. 2024. Value Creation Mechanisms in a Social and Health Care Innovation Ecosystem–An Institutional Perspective. Journal of Management and Governance 28: 1017–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Kamolika, Stephen Smilowitz, Sharvari Bhatt, and Mira L. Conroy. 2023. Impact of social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Current understanding and future directions. Current Geriatrics Reports 12: 138–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadabadi, Ali Asghar, Saeed Ramezani, Kiarash Fartash, and Iman Nikijoo. 2022. Social innovation: Drawing and analysis with using research in scientific base. Journal of Information and Knowledge Management 21: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, Alexander, and Benedikt Hassler. 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness among older adults. Frontiers in Sociology 5: 590935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIA-ADINBERRI. 2022. Envejecimiento activo y de valor. Bilbao: SIA-ADINBERRI. Available online: https://sia.adinberri.eus/documents/863739/0/SIA-Informe-tem%C3%A1tico-N2-Envejecimiento+activo+y+de+valor-ES.pdf/58eb985d-f44e-ac54-968a-9f70f7aa0ac8?t=1671031055669 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Smith, Adrian, Jan-Peter Voß, and John Grin. 2010. Innovation Studies and Sustainability Transitions: The Allure of the Multi-Level Perspective and Its Challenges. Research Policy 39: 435–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Care and Social Services Department. 2025. White Paper: Implementation and Stabilization of Local Care Ecosystems. Donostia-San Sebastián: Social Care and Social Services Department. [Google Scholar]

- Thinley, Sangay. 2021. Health and care of an ageing population: Alignment of health and social systems to address the need. Journal of Health Management 23: 109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unceta, Alfonso, Javier Castro-Spila, and Álvaro Luna. 2017. Social innovation communities. International Journal of Learning and Change 9: 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unceta, Alfonso, Javier Castro-Spila, and José G. Fronti. 2016. Social innovation indicators. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 29: 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribarri, Miren Barañano, Arantza Uriarte-Goikoetxea, and Miren Legarreta-Iza. 2024. Iniciativas público-comunitarias de cuidado a personas mayores: Oportunidades y retos para la transformación en el Ecosistema Local de Cuidado de Zestoa. RES. Revista Española de Sociología 33: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, Bart, and Patricia Van den Broeck. 2013. Social innovation: A territorial process. In The International Handbook on Social Innovation. Edited by Francesco Moulaert, Diana MacCallum, Abid Mehmood and Abdelillah Hamdouch. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, William H., Viktor J. J. M. Bekkers, and Lars G. Tummers. 2015. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Management Review 17: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, Frances, Nino Antadze, Dana J. Riddell, Kris Robinson, and Sean Geobey. 2014. Five Configurations for Scaling Up Social Innovation: Case Examples of Nonprofit Organizations From Canada. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 50: 234–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2025. Ageing: Global Population [Q&A]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/population-ageing (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Zheng, Xiaoying, Lihua Pang, Gong Chen, Chengli Huang, Lan Liu, and Lei Zhang. 2016. Challenge of population aging on health. In Public Health Challenges in Contemporary China. Edited by Manhong Islam. Berlin: Springer, pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zurynski, Yvonne, Jessica Herkes-Deane, Joanna Holt, Elise McPherson, Gina Lamprell, Genevieve Dammery, Isabelle Meulenbroeks, Nicole Halim, and Jeffrey Braithwaite. 2022. How Can the Healthcare System Deliver Sustainable Performance? A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 12: e059207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Spila, J.; Alonso González, D.; Brea-Iglesias, J.; Moriones García, X. Social Innovation and Social Care: Local Solutions to Global Challenges. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080479

Castro-Spila J, Alonso González D, Brea-Iglesias J, Moriones García X. Social Innovation and Social Care: Local Solutions to Global Challenges. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080479

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Spila, Javier, David Alonso González, Juan Brea-Iglesias, and Xanti Moriones García. 2025. "Social Innovation and Social Care: Local Solutions to Global Challenges" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080479

APA StyleCastro-Spila, J., Alonso González, D., Brea-Iglesias, J., & Moriones García, X. (2025). Social Innovation and Social Care: Local Solutions to Global Challenges. Social Sciences, 14(8), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080479