From Academia to Algorithms: Digital Cultural Capital of Public Intellectuals in the Age of Platformization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cultural Capital in the Age of Platformization

3. Celebrity Capital: A Re-Organization

4. Visibility Metrics as Digital Cultural Capital: The Ability of Code-Switching

5. Influences Behind Visibility: The Formation of Cultural Capital from Below

6. Populist Logics and the Selective Visibility of Digital Cultural Capital from Below

7. Conclusions: Directions of Future Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

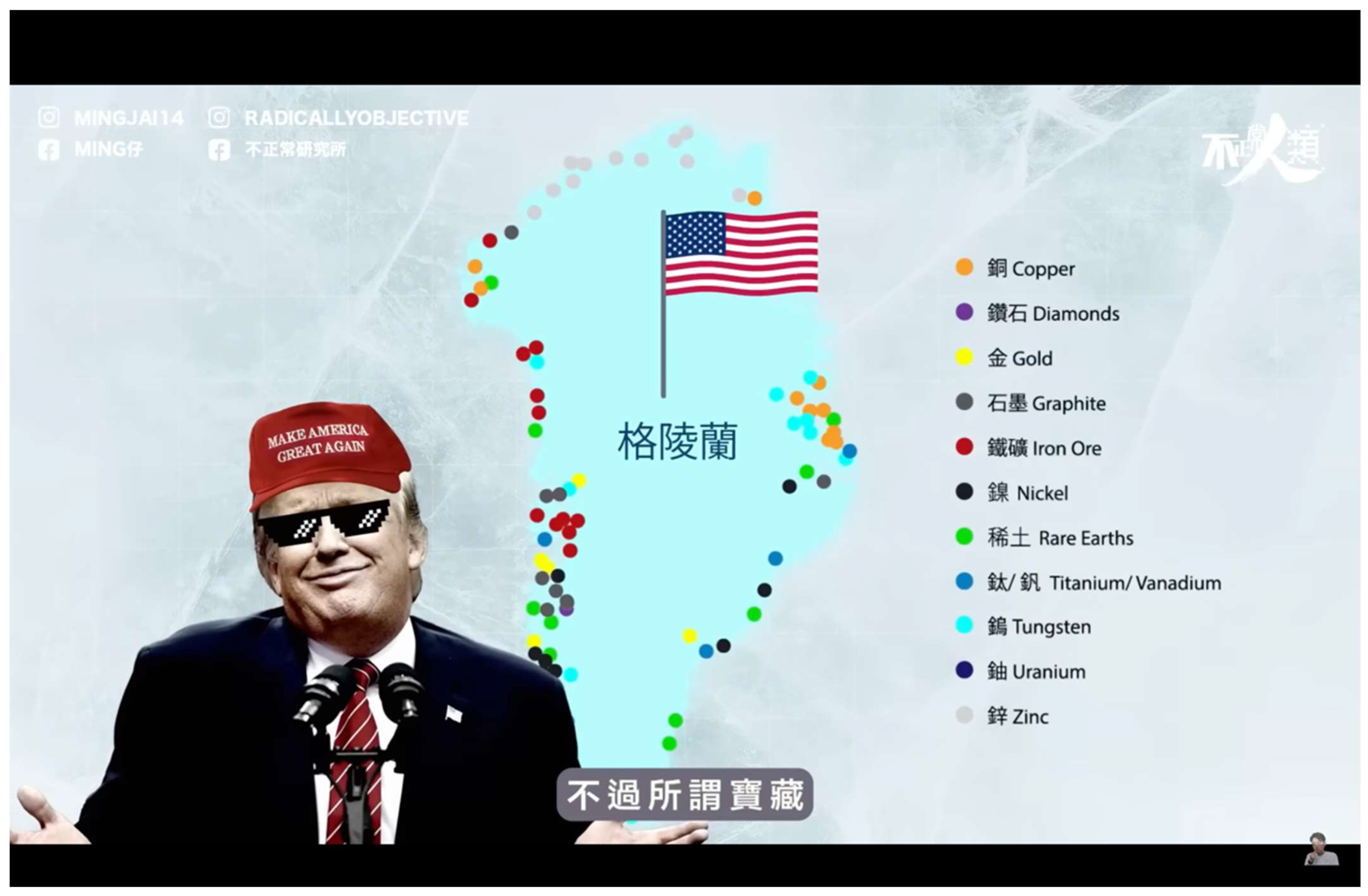

| 1 | The image is taken from a video analyzing the reasons behind Trump’s interest in Greenland. Using a map-based visual explanation, Mingjai identifies the distribution of Greenland’s natural resources, marked by colored dots corresponding to a legend on the right, which lists each resource in both Chinese and English. In the foreground, Trump is depicted wearing a “Make America Great Again” red cap and pixelated sunglasses, evoking an internet meme-style “deal with it” persona that symbolizes arrogance or defiant confidence. The text at the bottom of the image is a subtitle unrelated to the map, translating to “these so-called treasures.” 【特朗普上任】為何不排除武力爭奪格陵蘭?|「撐侵與反侵」 二元思考陷阱|美國欲吞併冰封領土的原因|佈局監視中俄在北極動向?(Trump Takes Office: Why Not Rule Out the Use of Force to Seize Greenland? | The “Pro-Invasion vs. Anti-Invasion” Binary Thinking Trap | Reasons Behind America’s Desire to Annex the Frozen Territory | Strategic Moves to Monitor China and Russia’s Arctic Activities). YouTube Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N5ktwMmIC3c&t=428s (accessed on 30 May 2025). |

| 2 | The image is from a video discussing the rise of the Mongol Empire. Using comic-style illustrations, Cheap presents historical figures in a more approachable manner. In this scene, a Mongol character is shown with a confused expression, reflecting the narration’s emphasis on the difficulty of ruling a population of approximately 100 million people with only 600,000 to 1 million Mongols. The subtitle at the bottom, unrelated to the specific frame, translates to “Mongolia’s ambition.” 60萬人橫掃歐亞大陸【蒙古帝國是怎麼崛起的】從小部落變成史上最大帝國 (600,000 People Swept Across Eurasia: [How the Mongol Empire Rose]—From a Small Tribe to the Largest Empire in History). YouTube Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcpFGO1Qvso (accessed on 30 May 2025). |

References

- Abidin, Crystal. 2015. Communicative Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 8: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, Crystal. 2018. Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, Crystal. 2021. From ‘Networked Publics’ to ‘Refracted Publics’: A Companion Framework for Researching ‘Below the Radar’ Studies. Social Media + Society 7: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldous, Kholoud Khalil, Jisun An, and Bernard J. Jansen. 2019. View, Like, Comment, Post: Analyzing User Engagement by Topic at 4 Levels across 5 Social Media Platforms for 53 News Organizations. Paper presented at Thirteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2019), München, Germany, June 11–14; pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Arthurs, Jane, and Sylvia Shaw. 2016. Celebrity Capital in the Political Field: Russell Brand’s Migration from Stand-Up Comedy to Newsnight. Media, Culture & Society 38: 1136–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-El, Eliran. 2023. How Slavoj Became Žižek: The Digital Making of a Public Intellectual. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bashiri, Farzana. 2024. Conceptualizing Scholar-Activism Through Scholar-Activist Accounts. In Making Universities Matter. Edited by Per Mattsson, Erik Perez Vico and Linus Salö. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beel, David, and Claire Wallace. 2020. Gathering Together: Social Capital, Cultural Capital and the Value of Cultural Heritage in a Digital Age. Social & Cultural Geography 21: 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bigthink. 2011. Judith Butler: Your Behavior Creates Your Gender|Big Think. YouTube Video, 3:00. June 6. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo7o2LYATDc (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- bigthink. 2023. Berkeley Professor Explains Gender Theory|Judith Butler. YouTube Video, 13:23. June 8. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UD9IOllUR4k (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Bishop, Sophie. 2019. Managing Visibility on YouTube through Algorithmic Gossip. New Media & Society 21: 2589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boler, Megan, and Elizabeth Davis. 2018. The Affective Politics of the “Post-Truth” Era: Feeling Rules and Networked Subjectivity. Emotion, Space and Society 27: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John Richardson. Westport: Greenwood, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brachaniec, Mary, Vince De Paul, Margaret Elliott, Lynn Moore, and Pamela Sherwin. 2009. Partnership in Action: An Innovative Knowledge Translation Approach to Improve Outcomes for Persons with Fibromyalgia. Physiotherapy Canada 61: 123–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Rebecca. 2011. Fetishising Intellectual Achievement: The Nobel Prize and European Literary Celebrity. Celebrity Studies 2: 320–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighenti, Andrea Mubi. 2010. Visibility in Social Theory and Social Research. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Gillian, Jenna Drenten, and Mikolaj Jan Piskorski. 2021. Influencer Celebrification: How Social Media Influencers Acquire Celebrity Capital. Journal of Advertising 50: 528–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Duncan, and Nick Hayes. 2008. Influencer Marketing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, Taina. 2012. Want to Be on the Top? Algorithmic Power and the Threat of Invisibility on Facebook. New Media & Society 14: 1164–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillat, François A., and Jasmina Ilicic. 2019. The Celebrity Capital Life Cycle: A Framework for Future Research Directions on Celebrity Endorsement. Journal of Advertising 48: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Albert, Chris Nickson, Jenny Rudolph, Anna Lee, and Gavin M. Joynt. 2020. Social Media for Rapid Knowledge Dissemination: Early Experience from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anaesthesia 75: 1579–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Leslie, and Pierre Mounier, eds. 2019. Connecting the Knowledge Commons—From Projects to Sustainable Infrastructure: The 22nd International Conference on Electronic Publishing—Revised Selected Papers. Laboratoire d’idées. Marseille: OpenEdition Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Li, and Carol Liebler. 2023. #MeToo on Twitter: The Migration of Celebrity Capital and Social Capital in Online Celebrity Advocacy. New Media & Society 26: 5403–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, T. Bettina, and Helen Katz. 2020. Influencer: The Science Behind Swaying Others. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry, Nick. 2003. Media Meta-Capital: Extending the Range of Bourdieu’s Field Theory. Theory and Society 32: 653–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, Thomas H., and John C. Beck. 2001. The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, Lisette, Sonja Gensler, and Peter S. H. Leeflang. 2012. Popularity of Brand Posts on Brand Fan Pages: An Investigation of the Effects of Social Media Marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing 26: 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul, and John Mohr. 1985. Cultural Capital, Educational Attainment, and Marital Selection. American Journal of Sociology 90: 1231–61. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2779635 (accessed on 30 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul. 1982. Cultural Capital and School Success: The Impact of Status Culture Participation on the Grades of U.S. High School Students. American Sociological Review 47: 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessens, Olivier. 2013a. Celebrity Capital: Redefining Celebrity Using Field Theory. Theory and Society 42: 543–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessens, Olivier. 2013b. The Celebritization of Society and Culture: Understanding the Structural Dynamics of Celebrity Culture. International Journal of Cultural Studies 16: 641–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer-Witheford, Nick. 2005. Cyber-Marx: Cycles and Circuits of Struggle in High Technology Capitalism. Uploaded 29 July 2005. Available online: https://libcom.org/article/cyber-marx-cycles-and-circuits-struggle-high-technology-capitalism-nick-dyer-witheford (accessed on 30 March 2025). First published 1999.

- Dyer-Witheford, Nick. 2020. Left Populism and Platform Capitalism. tripleC 18: 116–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, Jürgen. 2005. Border Crossings: Research Training, Knowledge Dissemination and the Transformation of Academic Work. Higher Education 49: 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, Nathan. 2019. Introduction: ‘Getting Busy with the Fizzy’—Johansson, SodaStream, and Oxfam: Exploring the Political Economics of Celebrity Activism. In The Political Economy of Celebrity Activism. Edited by Nathan Farrell. London: Routledge, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 2019. Discourse and Truth and Parresia. Edited by Henri-Paul Fruchaud and Daniele Lorenzini. Introduction by Frédéric Gros. Translated by Nancy Luxon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Charlotte. 2017. Going from PhD to Platform. In The Digital Academic: Critical Perspectives on Digital Technologies in Higher Education. Edited by Deborah Lupton, Inger Mewburn and Pat Thomson. London: Routledge, pp. 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2010. The Politics of ‘Platforms’. New Media & Society 12: 347–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, Henry A. 2010. Public Values, Higher Education and the Scourge of Neoliberalism: Politics at the Limits of the Social. In Culture Machine. London: Interzone. Available online: https://culturemachine.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/426-804-1-PB.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Godsteammate. 2024. The Best Right-Wing Psychologist vs. White Leftist Host/Haha, Trap You. YouTube Video, 37:38. December 11. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IC_YyrWlnpg&t=1s (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Goldhaber, Michael H. 2006. The Value of Openness in an Attention Economy. First Monday 11. Available online: https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1334 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Gómez, Daniel Calderón. 2021. The Third Digital Divide and Bourdieu: Bidirectional Conversion of Economic, Cultural, and Social Capital to (and from) Digital Capital among Young People in Madrid. New Media & Society 23: 2534–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Neil. 2002. Becoming a Pragmatist Philosopher: Status, Self-Concept, and Intellectual Choice. American Sociological Review 67: 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumperz, John J., and Dell Hymes, eds. 1972. Directions in Sociolinguistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Susan, and Eric Louw. 2019. ‘Bring Back Our Girls’: Social Celebrity, Digital Activism, and New Femininity. In The Political Economy of Celebrity Activism. Edited by Nathan Farrell. London: Routledge, pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Huberman, Bernardo A., Daniel M. Romero, and Fang Wu. 2009. Crowdsourcing, Attention and Productivity. Journal of Information Science 35: 758–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Erik J., J. Henri Burgers, and Per Davidsson. 2009. Celebrity Capital as a Strategic Asset: Implications for New Venture Strategies. In Entrepreneurial Strategic Content. Edited by G. T. Lumpkin and Jerome A. Katz. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 137–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, Janet R., and Michael Huberman. 1994. Knowledge Dissemination and Use in Science and Mathematics Education: A Literature Review. Journal of Science Education and Technology 3: 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inger, Mewburn, and Pat Thomson. 2017. Towards an Academic Self? In The Digital Academic. Edited by Deborah Lupton, Inger Mewburn and Pat Thomson. London: Routledge, pp. 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannotte, M. Sharon. 2022. Digital Platforms and Analogue Policies: Governance Issues in Canadian Cultural Policy. Canadian Journal of Communication 47: 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JordanBPeterson. 2020. Return Home. YouTube Video, 8:04. October 19. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_6zwVNn88o&t=12s (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- JordanBPeterson. 2023. JBP X @MattRifeComedy. Today at 5pm EST. YouTube Shorts, 0:24. November 30. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/bVh2cgpGM6o (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Joshi, K. D., Saonee Sarker, and Suprateek Sarker. 2007. Knowledge Transfer within Information Systems Development Teams: Examining the Role of Knowledge Source Attributes. Decision Support Systems 43: 322–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Jeremy M. 2009. Disseminating Clinical Trial Results in Critical Care. Critical Care Medicine 37 S1: S147–S153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Uttam, and Prashant Kumar Siddhey. 2024. Introduction to Influencer Marketing and Data Analytics. In Advances in Data Analytics for Influencer Marketing: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Edited by Soumi Dutta, Álvaro Rocha, Pushan Kumar Dutta, Pronaya Bhattacharya and Ramanjeet Singh Engineering. Information Systems Engineering and Management. Cham: Springer, vol. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kember, Sarah. 2024. Householding: A Feminist Ecological Economics of Publishing. Culture Machine 23. Available online: https://culturemachine.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/CM23_Kember_Householding.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Khoo, Tseen. 2017. Sustaining Asian Australian Scholarly Activism Online. In The Digital Academic. Edited by Deborah Lupton, Inger Mewburn and Pat Thomson. London: Routledge, pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kompatsiaris, Panos. 2019. Celebrity Activism and Revolution: The Problem of Truth and the Limits of Performativity. In The Political Economy of Celebrity Activism. Edited by Nathan Farrell. London: Routledge, pp. 151–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumasondjaja, Sony, and Fandy Tjiptono. 2019. Endorsement and Visual Complexity in Food Advertising on Instagram. Internet Research 29: 659–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labinaz, Paolo, and Marina Sbisà. 2021. The Problem of Knowledge Dissemination in Social Network Discussions. Journal of Pragmatics 175: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafrenière, Darquise, Vincent Menuz, Thierry Hurlimann, and Béatrice Godard. 2013. Knowledge Dissemination Interventions: A Literature Review. SAGE Open 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, Michèle. 2010. How Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic Judgment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, Annette, and Elliot B. Weininger. 2003. Cultural Capital in Educational Research: A Critical Assessment. Theory and Society 32: 567–606. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3649652 (accessed on 30 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Leban, Marina, and Benjamin G. Voyer. 2020. Social Media Influencers versus Traditional Influencers: Roles and Consequences for Traditional Marketing Campaigns. In Influencer Marketing. Edited by Joyce Costello and Sevil Yesiloglu. London: Routledge, pp. 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jumin, Do-Hyung Park, and Ingoo Han. 2011. The Different Effects of Online Consumer Reviews on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions Depending on Trust in Online Shopping Malls: An Advertising Perspective. Internet Research 21: 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Hsin-Chen, Patrick F. Bruning, and Hepsi Swarna. 2018. Using Online Opinion Leaders to Promote the Hedonic and Utilitarian Value of Products and Services. Business Horizons 61: 431–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Lisa. 2018. Native Advertising: Advertorial Disruption in the 21st Century News Feed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mansur, Vinicius, Clara Guimarães, Marilia Sá Carvalho, Luciana Dias de Lima, and Claudia Medina Coeli. 2021. From Academic Publication to Science Dissemination. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 37: e00140821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, Alice E. 2015. You May Know Me from YouTube: (Micro-)Celebrity in Social Media. In A Companion to Celebrity. Edited by P. David Marshall and Sean Redmond. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 333–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mattke, Jens, Christian Maier, Lea Reis, and Tim Weitzel. 2020. Herd Behavior in Social Media: The Role of Facebook Likes, Strength of Ties, and Expertise. Information & Management 57: 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. Wright. 1958. The Causes of World War Three. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Aimée. 2018. Of, By, and For the Internet: New Media Studies and Public Scholarship. In The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities. Edited by Jentery Sayers. London: Routledge, pp. 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer, Christina, Luca Rossi, and David M. Struthers. 2021. Invisible Data: A Framework for Understanding Visibility Processes in Social Media Data. Social Media + Society 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollier-Malaterre, Ariane, Jerry A. Jacobs, and Nancy P. Rothbard. 2019. Technology, Work, and Family: Digital Cultural Capital and Boundary Management. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 425–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paino, Maria, and Linda A. Renzulli. 2013. Digital Dimension of Cultural Capital: The (In)Visible Advantages for Students Who Exhibit Computer Skills. Sociology of Education 86: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Chang Sup. 2013. Does Twitter Motivate Involvement in Politics? Tweeting, Opinion Leadership, and Political Engagement. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 1641–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, Caitlin, Brooke Erin Duffy, and Emily Hund. 2019. Gaming the System: Platform Paternalism and the Politics of Algorithmic Visibility. Social Media + Society 5: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzalis, Marco, and Mariano Porcu. 2024. Digital Capital and Cultural Capital in Education: Unravelling Intersections and Distinctions That Shape Social Differentiation. British Educational Research Journal 50: 2753–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, Thomas, David B. Nieborg, and Brooke Erin Duffy. 2021. Platforms and Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana Ramos, Irene, and Fiona Cownie. 2020. Female Environmental Influencers on Instagram. In Influencer Marketing: Building Brand Communities and Engagement. Edited by Joyce Costello and Sevil Yesiloglu. London: Routledge, pp. 159–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, Muralidharan, Anup Shrestha, and Jeffrey Soar. 2021. Innovation Centric Knowledge Commons—A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Model. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, Srividya, and Alexandra N. Sousa. 2021. Communication Scholar-Activism: Conceptualizing Key Dimensions and Practices Based on Interviews with Scholar-Activists. Journal of Applied Communication Research 49: 477–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Wei, Xiaowen Zhu, and Jianghua Yang. 2022. The SES-Based Difference of Adolescents’ Digital Skills and Usages: An Explanation from Family Cultural Capital. Computers & Education 177: 104382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, Chris. 2001. Celebrity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 1996. Representations of the Intellectual. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Scolere, Leah. 2019. Brand Yourself, Design Your Future: Portfolio-Building in the Social Media Age. New Media & Society 21: 1891–909. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Yuri, Jungkeun Kim, Yung Kyun Choi, and Xiaozhu Li. 2019. In ‘Likes’ We Trust: Likes, Disclosures and Firm-Serving Motives on Social Media. European Journal of Marketing 53: 2173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- shasha77. 2024. Taiwan Gender Opposition More and More Serious? Exactly How Considered Misogyny? Regarding “Feminism Buffet”, Feminists Then How See? ft. Professor Kang Ting-Yu|Strong Person My Friend EP 098|Shasha 77 Podcast. 23 November. YouTube Video, 49:19. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VeU_ra_DYLE&t=786s (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Stiegler, Bernard. 2012. Relational Ecology and the Digital Pharmakon. Culture Machine 13. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=c2d5d9ccdcd147446187cd5378770d23a84ba5ab (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Thayne, Martyn. 2012. Friends like Mine: The Production of Socialised Subjectivity in the Attention Economy. Culture Machine 13. Available online: https://culturemachine.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/471-1021-1-PB.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Turner, Graeme. 2004. Understanding Celebrity. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ulysse, Gina A. 2007. Downtown Ladies: Informal Commercial Importers, a Haitian Anthropologist, and Self-Making in Jamaica. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2023. Knowledge Commons and Enclosures. July 7. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/knowledge-commons-and-enclosures (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- van de Ven, Inge, and Ties van Gemert. 2020. Filter Bubbles and Guru Effects: Jordan B. Peterson as a Public Intellectual in the Attention Economy. Celebrity Studies 13: 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Krieken, Robert. 2012. Celebrity Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Peter William, and David Lehmann. 2021. Academic Celebrity. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 34: 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, Brian E., Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga. 2017. Online Influence? Social Media Use, Opinion Leadership, and Political Persuasion. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 29: 214–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Bari. 2018. Meet the Renegades of the Intellectual Dark Web. The New York Times, May 8. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/08/opinion/intellectual-dark-web.html (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- West, Darrell M. 2008. Angelina, Mia, and Bono: Celebrities and International Development. In Global Development 2.0. Edited by Lael Brainard and Derek Chollet. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Milly. 2016. Celebrity, Capitalism and the Making of Fame. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Willson, Michele. 2014. The Politics of Social Filtering. Convergence 20: 218–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Yang, Zhichao Cheng, Enhe Liang, and Yinbo Wu. 2018. Accumulation Mechanism of Opinion Leaders’ Social Interaction Ties in Virtual Communities: Empirical Evidence from China. Computers in Human Behavior 82: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesiloglu, Sevil. 2020. The Rise of Influencers and Influencer Marketing. In Influencer Marketing, 1st ed. Edited by Joyce Costello and Sevil Yesiloglu. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Definition/Source | Relevance to the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Capital | Forms of capital (embodied, objectified, institutionalized) that confer social advantage | Provides the foundational framework for understanding traditional scholarly authority and its institutional bases. |

| Digital Cultural Capital | Technological and platform-based competencies and visibility metrics that confer influence | Explains how cultural capital is restructured online through engagement metrics like views, likes, and shares. |

| Cultural Capital from Below | Bottom-up recognition and legitimacy derived from community engagement and peer interaction | Highlights how digital recognition can bypass institutional validation, but also how it remains shaped by platform logics. |

| Celebrity/Influencer Capital | Symbolic power gained through media visibility, convertibility across domains | Shows how public intellectuals adopt tactics from influencer culture to cultivate public attention and legitimacy. |

| Code-Switching | The practice of shifting language or presentation styles across contexts | Describes the communicative flexibility scholars must adopt to navigate different publics and platforms. |

| Platform Logics | The algorithmic, metric-driven, and affect-oriented structures of digital platforms | Frames how visibility and influence are conditioned by platform-specific affordances, such as recommendation algorithms and engagement incentives. |

| Public Intellectuals | Scholars and thinkers who engage broader publics beyond academia | Discuss the central subject of the article—figures who must now navigate visibility economies to maintain authority and relevance. |

| Knowledge Mobilization | The process of translating and circulating knowledge beyond academic institutions | Underscores how scholars engage in outreach to impact public discourse, especially through platformized media. |

| Channel Name | Rank | Subscribers | Views | Videos | Category | Origins or Ethnicity | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| आचार्य प्रशांत - Acharya Prashant (@ShriPrashant) | 6th | 56M | 3.6B | 13K | Philosophy | India | Male |

| Dhruv Rathee (@dhruvrathee) | 18th | 28M | 4.1B | 676 | Politics | India | Male |

| Dr. Vivek Bindra: Motivational Speaker (@DrVivekBindra) | 30th | 21M | 2B | 2K | Business | India | Male |

| Pushkar Raj Thakur: Stock Market Educator (@PushkarRajThakur) | 59th | 14M | 1.2B | 1.9K | Business | India | Male |

| Doctor Mike (@doctormike) | 62th | 14M | 4.3B | 997 | Medicine | U.S. (White) | Male |

| Dr. Eric Berg DC (@drericberg) | 65th | 13M | 2.8B | 5.5K | Medicine | U.S. (White) | Male |

| SONU SHARMA (@sonusharmaofficial) | 70th | 12M | 1B | 436 | Business | India | Male |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, L.L.H. From Academia to Algorithms: Digital Cultural Capital of Public Intellectuals in the Age of Platformization. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060387

Wong LLH. From Academia to Algorithms: Digital Cultural Capital of Public Intellectuals in the Age of Platformization. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060387

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Lucas L. H. 2025. "From Academia to Algorithms: Digital Cultural Capital of Public Intellectuals in the Age of Platformization" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060387

APA StyleWong, L. L. H. (2025). From Academia to Algorithms: Digital Cultural Capital of Public Intellectuals in the Age of Platformization. Social Sciences, 14(6), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060387