Factors of Workplace Procrastination: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Accounts of Procrastination

1.2. Procrastination at Work: Consequences and Factors

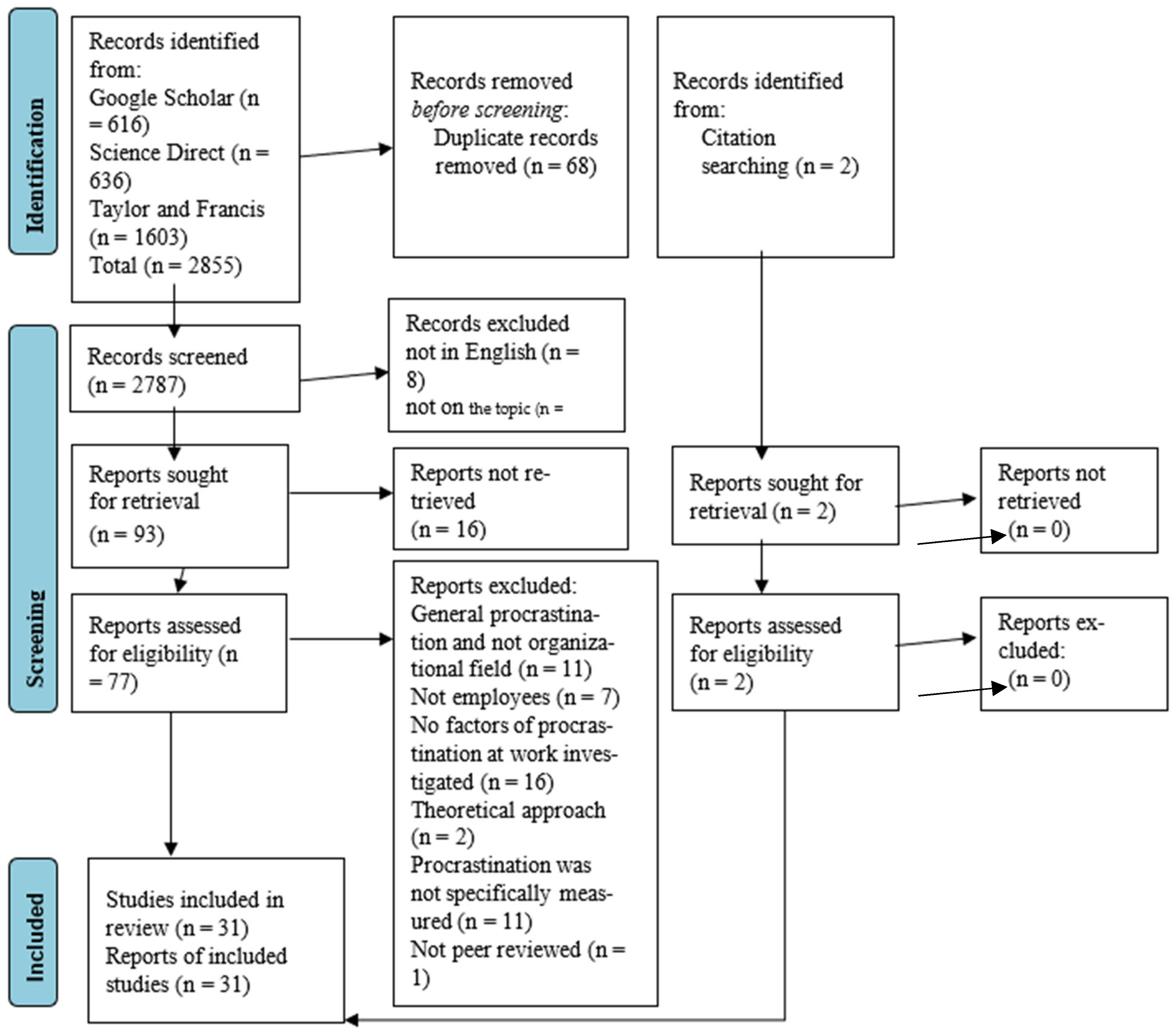

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

- The text was published in English and tables use the Latin alphabet;

- Published between 2000 and 2023;

- From the organizational field and refers to work tasks;

- Participants are employees, older than 18 years;

- In which procrastination was evaluated with a specific measure, and the name and authors of the instrument are presented;

- Procrastination is the dependent variable;

- With full text access;

- Published in peer review journals.

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Collection

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment

3.2. Study Design and Participants of the Included Studies

3.3. Measurement of Procrastination

3.4. Factors of Procrastination

3.5. Employee-Related Factors of Procrastination

3.5.1. Demographic Factors

3.5.2. Big-Five Personality Factors

3.5.3. Self-Concept

3.5.4. Emotional Factors

3.5.5. Work-Related Internal Factors

3.5.6. Cognitive Factors

3.5.7. Work-Life Balance

3.5.8. Personal Tendency to Procrastinate

3.6. External Factors of Procrastination

3.6.1. Work and Job Characteristics

3.6.2. Workload

3.6.3. Time Pressure

3.6.4. Leadership Style

3.6.5. Work Context

4. Discussion

Practical Implications

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, Tammy. D., Joyce E. A. Russell, Mark L. Poteet, and Gregory H. Dobbins. 1999. Learning and development factors related to perceptions of job content and hierarchical plateauing. Journal of Organizational Behavior 20: 1113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, Cecilie Schou, Torbjørn Torsheim, Geir Scott Brunborg, and Ståle Pallesen. 2012. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports 110: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariely, Dan, and Klaus Wertenbroch. 2002. Procrastination, Deadlines, and Performance: Self-Control by Precommitment. Psychological Science 13: 219–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asio, John Mark R., and Erin Riego de Dios. 2021. Demographic profiles and procrastination of employees: Relationships and determinants. International Journal of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences 7: 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, Avi, Maya Israeli-Halevi, and Guy Roth. 2009. Emotion Regulation Styles. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD), Denver, CO, USA, April 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Astakhova, Marina N., and Gayle Porter. 2015. Understanding the work passion–performance relationship: The mediating role of organizational identification and moderating role of fit at work. Human Relations 68: 1315–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and Bernard M. Bass. 2004. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. In Manual and Sampler Set, 3rd ed. Redwood City: Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, Bruce J., Bernard M. Bass, and Dong I. Jung. 1999. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 72: 441–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycan, Zeynep. 2006. Paternalism. In Indigenous and Cultural Psychology. Edited by Uichol Kim, Kuo-Shu Yang and Kwang-Kuo Hwang. International and Cultural Psychology. Boston: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 84: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2006. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Edited by Urdan Timothy and Pajares Frank. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, vol. 5, pp. 307–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Bruce J. Avolio. 1990. Developing transformational leadership: 1992 and beyond. Journal of European Industrial Training 14: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, Terry A., Jeffrey T. Walsh, and Thomas D. Taber. 1976. Relationships of stress to individually and organizationally valued states: Higher order needs as a moderator. Journal of Applied Psychology 61: 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Gary, and Kimberly Boal. 1989. Using job involvement and organizational commitment interactively to predict turnover. Journal of Management 15: 115–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, Rutger, Rick T. Borst, and Bart Voorn. 2021. Pathology or Inconvenience? A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Red Tape on People and Organizations. Review of Public Personnel Administration 41: 623–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Xiongfei, Xitong Guo, Doung Vogel, and Xi Zhang. 2016. Exploring the influence of social media on employee work performance. Internet Research 26: 529–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Abraham, Roni Reiter-Palmon, and Enbal Ziv. 2010. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Involvement in Creative Tasks in the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. Creativity Research Journal 22: 250–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalder, Trudie, G. Berelowitz, Teresa Pawlikowska, Louise Watts, Simon Wessely, David Wright, and E. Paul Wallace. 1993. Development of a fatigue scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 37: 147–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jin Nam, and Sarah V. Moran. 2009. Why Not Procrastinate? Development and Validation of a New Active Procrastination Scale. The Journal of Social Psychology 149: 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Angela Hsin Chun, and Jin Nam Choi. 2005. Rethinking Procrastination: Positive Effects of “Active” Procrastination Behavior on Attitudes and Performance. The Journal of Social Psychology 145: 245–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, Donna K., Katarina K. Brant, and Juanita M. Woods. 2019. The role of public service motivation in employee work engagement: A test of the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Public Administration 42: 765–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abate, Caroline P., and Erik R. Eddy. 2007. Engaging in personal business on the job: Extending the presenteeism construct. Human Resource Development Quarterly 18: 361–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Richard A., Gordon L. Flett, and Avi Besser. 2002. Validation of a new scale for measuring problematic Internet use: Implications for pre-employment screening. CyberPsychology & Behavior 5: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeArmond, Sarah, Russell A. Matthews, and Jennifer Bunk. 2014. Workload and procrastination: The roles of psychological detachment and fatigue. International Journal of Stress Management 21: 137–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, Dirk, Tasneem Fatima, and Sadia Jahanzeb. 2021. Cronies, procrastinators, and leaders: A conservation of resources perspective on employees’ responses to organizational cronyism. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 31: 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, Richard, and Norman D. Sundberg. 1986. Boredom proneness: The development and correlates of a new scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 50: 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gignac, Gilles. 2010. Seven-factor model of emotional intelligence as measured by Genos EI: A confirmatory factor analytic investigation based on self- and rater-report data. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 26: 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkorezis, Panagiotis, George Mousailidis, Petros Kostagiolas, and George Kritsotakis. 2021. Harmonious work passion and work-related internet information seeking among nurses: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Nursing Management 29: 2534–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Lewis R., John A. Johnson, Herbert W. Eber, Robert Hogan, Michael C. Ashton, C. Robert Cloninger, and Harrison G. Gough. 2006. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality 40: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goroshit, Marina, and Meirav Hen. 2018. Decisional, general and online procrastination: Understanding the moderating role of negative affect in the case of computer professionals. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 46: 279–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göncü Köse, A., and U. Baran Metin. 2018. Linking leadership style and workplace procrastination: The role of organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 46: 245–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, George B., and Terri A. Scandura. 1987. Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. In Research in Organizational Behavior. Edited by Larry L. Cummings and Bary M. Staw. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 9, pp. 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Karen M. Collins, and Jason D. Shaw. 2003. The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior 63: 510–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregov, Ljiljana J., and Ana Šimunić. 2012. Skala psiholoških zahtjeva i kontrole posla. In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika. Edited by Proroković Ana, Ćubela Adorić Vera, Penezić Zvjezdan and Ivana Tucak Junaković. Zadar: University of Zadar, vol. 6, pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Paul W., Meghan J. Millea, and Thomas W. Woodruff. 2004. Grades—Who’s to blame? Student evaluation of teaching and locus of control. The Journal of Economic Education 35: 129–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, Axel, and Stefan Fries. 2018. Understanding procrastination: A motivational approach. Personality and Individual Differences 121: 120–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Xinran, Guangyi Xu, Chen Qian, Saichao Chang, and Dandan Deng. 2022. Excess and Defect How Job-Family Responsibilities Congruence Effect the Employee Procrastination Behavior. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 15: 1465–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, Ritu, Douglas A. Hershey, and Jighyasu Gaur. 2012. Time Perspective and Procrastination in the Workplace: An Empirical Investigation. Current Psychology 31: 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harary, Keith, and Eileen Donahue. 1994. Ontdek de vele facetten van uw persoonlijkheid [Discover the many facets of your personality]. Psychologie 13: 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hen, Meirav. 2018. Causes for procrastination in a unique educational workplace. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 46: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, Meirav, and Marina Goroshit. 2018. General and life-domain procrastination in highly educated adults in Israel. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, Meirav, Marina Goroshit, and Stav Viengarten. 2021. How decisional and general procrastination relate to procrastination at work: An investigation of office and non-office workers. Personality and Individual Differences 172: 110581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Violet T., Sze-Sze Wong, and Chay Hoon Lee. 2011. A tale of passion: Linking job passion and cognitive engagement to employee work performance. Journal of Management Studies 48: 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2001. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology 50: 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, revised and expanded 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Quan Nha, Araceli Gonzalez-Reyes, and Pierre Pluye. 2018. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 24: 459–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Qiufeng, Kaili Zhang, Ali Ahmad Bodla, and Yanqun Wang. 2022. The Influence of Perceived Red Tape on Public Employees’ Procrastination: The Conservation of Resource Theory Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Qiufeng, Kaili Zhang, Yafang Huang, Ali Ahmad Bodla, and Xia Zou. 2023. The interactive effect of stressor appraisals and personal traits on employees’ procrastination behavior: The conservation of resources perspective. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutmanová, Nikoleta, Zuzana Hajduová, Peter Dorčák, and Vlastislav Laskovský. 2022. Prevention of procrastination at work through motivation enhancement in small and medium enterprises in Slovakia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 10: 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, Lozena. 2002. Skala opće samoefikasnosti. In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika. Edited by Lacković-Grgin Katica, Proroković Ana, Ćubela Vera and Penezić Zvjezdan. Zadar: University of Zadar, vol. 1, pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Christian Bøtcher, and Mads Leth Felsage Jakobsen. 2018. Perceived organizational red tape and organizational performance in public services. Public Administration Review 78: 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Oliver P., and Sanjay Srivastava. 1999. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Edited by Lawrence A. Pervin and Oliver P. John. New York: Guilford Press, vol. 2, pp. 102–38. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Gary. 2011. Attendance dynamics at work: The antecedents and correlates of presenteeism, absenteeism, and productivity loss. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 16: 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Rober Paul. 2020. Passion meets procrastination: Comparative study of negative sales associate behaviours. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 48: 1077–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanten, Pelin, and Selahattin Kanten. 2016. The antecedents of procrastination behavior: Personality characteristics, self-esteem and self-efficacy. PressAcademia Procedia 2: 331–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshouei, Mahdieh Sadat. 2017. Prediction of Procrastination Considering Job Characteristics and Locus of Control in Nurses. Journal of Holistic Nursing and Midwifery 27: 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingsieck, Katrin B. 2013. Procrastination. European Psychologist 18: 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, Linda, Claire Bernaards, Vincent Hildebrandt, Stef Van Buuren, Allard J. Van der Beek, and Henrica C. De Vet. 2012. Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 62: 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Kathrin, and Alexandra M. Freund. 2014. Delay or procrastination–A comparison of self-report and behavioral measures of procrastination and their impact on affective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 63: 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, Glen E., and Blake E. Ashforth. 2004. Evidence toward and expanded model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, Bettina, Matea Paškvan, and Christian Korunka. 2015. Development and validation of an instrument for assessing job demands arising from accelerated change: The intensification of job demands scale (IDS). European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 24: 898–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, Bård. 2006. Work performance, affective commitment, and work motivation: The roles of pay administration and pay level. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27: 365–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, Jana, Ronald Bledow, and Angela Kuonath. 2022. Overcoming procrastination: Time pressure and positive affect as compensatory routes to action. Journal of Business and Psychology 38: 803–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, Jana, Ronald Bledow, and Nicolas Feuerhahn. 2016. When do you pro-crastinate? Sleep quality and social sleep lag jointly predict self-regulatory failure at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior 37: 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, Clarry H. 1986. At last, my research article on procrastination. Journal of Research in Personality 20: 474–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Han. 2018. The Effect of Inclusive Leadership on Employees’ Procrastination. Psychology 9: 714–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukidou, Lia, John Loan-Clarke, and Kevin Daniels. 2009. Boredom in the workplace: More than monotonous tasks. International Journal of Management Reviews 11: 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, Peter F., and Syd H. Lovibond. 1995. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy 33: 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macan, Therese Hoff. 1994. Time management: Test of a process model. Journal of Applied Psychology 79: 381–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Leon. 1982. Decision Making Questionnaire. Adelaide: Flinders University of South Australia, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Leon. 2016. Procrastination revisited: A commentary. Australian Psychologist 51: 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Leon, Paul Burnett, Mark Radford, and Steve Ford. 1997. The Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: An instrument for measuring patterns for coping with decisional conflict. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, Douglas C., and Natalya M. Parfyonova. 2013. Perceived overqualification and withdrawal behaviours: Examining the roles of job attitudes and work values. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 86: 435–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, Douglas C., Todd Allen Joseph, and Amanda M. Maynard. 2006. Underemployment, job attitudes, and turnover intentions. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27: 509–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymäki, Matti, and A. K. M. Najmul Islam. 2016. The Janus face of Facebook: Positive and negative sides of social networking site use. Computers in Human Behavior 61: 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, Justin. 2011. Finally, My Thesis on Academic Procrastination. Master’s thesis, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McCown, William, and Judith Johnson. 1989. Validation of an Adult Inventory of Procrastination. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Personality Assessment, New York, NY, USA, April 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- McCown, William, and Judith Johnson. 1991. Personality and chronic procrastination by university students during an academic examination period. Personality and Individual Differences 12: 413–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, Robert R., and Paul T. Costa, Jr. 2008. The five-factor theory of personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 3rd ed. Edited by Oliver P. John, Richard W. Robins and Lawrence A. Pervin. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- Metin, Ümit Baran, Maria C. W. Peeters, and Toon W. Taris. 2018. Correlates of procrastination and performance at work: The role of having “good fit”. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 46: 228–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, Ümit Baran, Toon W. Taris, and Maria C. Peeters. 2016. Measuring Procrastination at Work and Its Associated Workplace Aspects. Personality and Individual Differences 101: 254–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Rustin D., Reeshad S. Dalal, and Silvia Bonaccio. 2009. A meta-analytic investigation into the moderating effects of situational strength on the conscientiousness-performance relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior 30: 1077–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharram-Nejadifard, Monireh, Omid Saed, Seyede Solmaz Taheri, and Elahe Ahmadnia. 2020. The effect of cognitive behavioural group therapy on the workplace and decisional procrastination of midwives: A randomized controlled trial. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 25: 514–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgeson, Frederick P., and Stephen E. Humphrey. 2006. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 1321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, Pilar, Maria Eduarda Soares, Paul Dordio, and Leonor Atayde e Melo. 2022. The thief of time and social sustainability: Analysis of a procrastination at work model. Revista de Administração de Empresas 62: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Brenda, Piers Steel, and Joseph R. Ferrari. 2013. Procrastination’s Impact in the Workplace and the Workplace’s Impact on Procrastination. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 21: 388–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Ulrich, and Richard W. Robins. 2014. The development of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science 23: 381–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 71: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, Udai, Surabhi Purohit, and Aroon Joshi. 2011. Training instruments. In HRD and OD, 3rd ed. Edited by Pareek Udai and Purohit Surabhi. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hills Publishing Company Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman-Avnion, Shiri, and Alexander Zibenberg. 2018. Prediction and job-related outcomes of procrastination in the workplace. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 46: 263–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, Paraskevas, Evanghelia Demerouti, Maria C. Peeters, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Jørn Hetland. 2012. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior 33: 1120–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Robert H. Moorman, and Richard Fetter. 1990. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly 1: 107–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, Roman, Tabea E. Scheel, Oliver Weigelt, Katja Hoffmann, and Christian Korunka. 2018. Procrastination in Daily Working Life: A Diary Study on Within-Person Processes That Link Work Characteristics to Workplace Procrastination. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, Andrew K., Kou Murayama, Cody R. DeHaan, and Valerie Gladwell. 2013. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 1841–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reić Ercegovac, Ina, and Zvjezdan Penezić. 2012. Skala depresivnosti, anksioznosti i stresa (DASS). In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika. Edited by Proroković Ana, Ćubela Adorić Vera, Penezić Zvjezdan and Ivana Tucak Junaković. Zadar: University of Zadar, vol. 6, pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reijseger, Gaby, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Maria C. W. Peeters, Toon W. Taris, Ilona van Beek, and Else Ouweneel. 2012. Watching the paint dry at work: Psychometric examination of the Dutch Boredom Scale. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 26: 508–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, Leonard, Adrian Meier, Manfred E. Beutel, Christian Schemer, Birgit Stark, Klaus Wölfling, and Kai W. Müller. 2018. The relationship between trait procrastination, internet use, and psychological functioning: Results from a community sample of German adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, Leonard, Tilo Hartmann, and Allison Eden. 2014. The guilty couch potato: The role of ego depletion in reducing recovery through media use. The Journal of Communication 64: 569–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, Sonja, Myriam N. Bechtoldt, and Mona Leonhardt. 2016. Validation of the Impostor Phenomenon among Managers. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romppel, Matthias Christoph Herrmann-Lingen, Rolf Wachter, Frank Edelmann, Hans-Dirk Düngen, Burkert Pieske, and Gesine Grande. 2013. A short form of the general self-efficacy scale (GSE-6): Development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non-clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine 10: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Morris. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Rozental, Alexander, and Per Carlbring. 2014. Understanding and Treating Procrastination: A Review of a Common Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychology 5: 1488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, Marian N., Patricia J. Ohlott, Kate Panzer, and Sara N. King. 2002. Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Academy of Management Journal 45: 369–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, Alan M. 1995. Longitudinal field investigation of the moderating and mediating effects of self-efficacy on the relationship between training and newcomer adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology 80: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, John, John L. Cotton, and Kenneth R. Jennings. 1989. Antecedents and consequences of role stress: A covariance structure analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior 10: 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2003. Test Manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Utrecht: Utrecht University, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Arnold B. Bakker, and Marisa Salanova. 2006. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement 66: 701–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Michael P. Leiter, Christina Maslach, and Susan E. Jackson. 1996. The Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey. In Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed. Edited by Maslach Christina, Susan E. Jackson and Michael P. Leiter. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Klaus-Helmut, and Barbara Neubach. 2010. Selbstkontrollanforderungen bei der arbeit. Fragebogen zur erfassung eines bislang wenig beachteten belastungsfaktors [Self-control demands—Questionnaire for measuring a so far neglected job stressor]. Diagnostica 56: 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, Ralf, and Matthias Jerusalem. 1995. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs. Edited by John Weinman, Stephen C. Wright and Marie Johnston. Windsor: NFER-NELSON, pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, Ralf, Judith Bäsler, Patricia Kwiatek, Kerstin Schröder, and Jian Xin Zhang. 1997. The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Applied Psychology 46: 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, Ben J., and Jaime C. Auton. 2015. The merits of measuring challenge and hindrance appraisals. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 28: 121–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, Norberth K., Dieter Zapf, and Heiner Dunckel. 1999. Instrument zur Stressbezogenen Tätigkeitsanalyse ISTA [Instrument for stress-related job analysis]. In Handbuch Psycholo-Gischer Arbeitsanalyseverfahren. Edited by Dunckel Heiner. Zürich: Vdf Hochschulverlag, pp. 179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Abhishek, and Ankita Sharma. 2021. Turnover Intention and Procrastination: Causal Contribution of Work-Life (Im) Balance. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government 27: 1891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Amy, and Jay Choi. 2022. Big Five personality traits predicting active procrastination at work: When self- and supervisor-ratings tell different stories. Journal of Research in Personality 99: 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, Johannes, Dagmar Starke, Tarani Chandola, Isabelle Godin, Michael Marmot, Isabelle Niedhammer, and Richard Peter. 2004. The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Social Science & Medicine 58: 1483–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Sandeep, and Rajni Bala. 2020. Mediating role of self-efficacy on the relationship between conscientiousness and procrastination. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion 11: 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Sandeep, Sarita Sood, and Rajni Bala. 2021. Passive leadership styles and perceived procrastination in leaders: A PLS-SEM approach. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 17: 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, Fuschia M. 2023. Procrastination and stress: A conceptual review of why context matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, Fuschia M., and Timothy Pychyl. 2013. Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 7: 115–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, Fuschia M., Sisi Yang, and Wandelien van Eerde. 2019. Development and validation of the General Procrastination Scale (GPS-9): A short and reliable measure of trait procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences 146: 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Paul E. 1988. Development of the Work Locus of Control Scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology 61: 335–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Paul E., and Steve M. Jex. 1998. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 3: 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Paul E., Suzy Fox, Lisa M. Penney, Kari Bruursema, Angeline Goh, and Stacey Kessler. 2006. The dimensionality of counterproductivity: Are all counterproductive behaviors created equal? Journal of Vocational Behavior 68: 446–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamper, Christina L., and Suzanne S. Masterson. 2002. Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 23: 875–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers. 2007. The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychological Bulletin 133: 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers. 2010. Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist? Personality and Individual Differences 48: 926–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers, and Cornelius J. König. 2006. Integrating Theories of Motivation. Academy of Management Review 31: 889–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers, and Joseph Ferrari. 2013. Sex, Education and procrastination: An epidemiological study of procrastinators’ characteristics from a global sample. European Journal of Personality 27: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers, Daphne Taras, Allen Ponak, and John Kammeyer-Mueller. 2022. Self-Regulation of Slippery Deadlines: The Role of Procrastination in Work Performance. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 783789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svartdal, Frode, and Piers Steel. 2017. Irrational Delay Revisited: Examining Five Procrastination Scales in a Global Sample. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šuvak-Martinović, Marijana, and Ivona Čarapina Zovko. 2017. Procrastination: Relations with mood, self-efficacy, perceived control and task demands. Suvremena Psihologija 20: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, Anushree, Amandeep Dhir, Nazrul Islam, Shalini Talwar, and Matti Mäntymäki. 2021. Psychological and behavioral outcomes of social media-induced fear of missing out at the workplace. Journal of Business Research 136: 186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbett, Thomas P., and Joseph R. Ferrari. 2015. The portrait of the procrastinator: Risk factors and results of an indecisive personality. Personality and Individual Differences 82: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckman, Bruce W. 1991. The development and concurrent validity of the Procrastination Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement 51: 473–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudose, Cristina Maria, and Mariela Pavalache-Ilie. 2021. Procrastination and work satisfaction. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov. Series VII, Social Sciences and Law 14: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, Muhammed. 2014. Organizational cronyism: A scale development and validation from the perspective of teachers. Journal of Business Ethics 123: 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, H. Tezcan, and Fatma Yilmaz. 2020. Procrastination in the workplace: The role of hierarchical career plateau. Upravlenec 11: 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, Robert J., Celine Blanchard, Genevieve A. Mageau, Richard Koestner, Catherine Ratelle, Maude Leonard, Marylene Gagne, and Josee Marsolais. 2003. Les passions de l’ame: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 756–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, Ralph, and Toon W. Taris. 2014a. Authenticity at work: Development and validation of an individual authenticity measure at work. Journal of Happiness Studies 15: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, Ralph, and Toon W. Taris. 2014b. The authentic worker’s well-being and performance: The relationship between authenticity at work, well-being, and work outcomes. The Journal of Psychology 148: 659–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eerde, Wendelien. 1998. Work Motivation and Procrastination: Self-Set Goals and Action Avoidance. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- van Eerde, Wendelien. 2003. Procrastination at work and time management training. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 137: 421–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eerde, Wendelien. 2016. Procrastination and well-being at work. In Procrastination, Health, and Well-Being. Edited by Fuschia. M. Sirois and Timothy A. Pychyl. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veldhoven, Marc, and Theo F. Meijman. 1994. Het meten van psychosociale arbeidsbelasting met een vragenlijst: De Vragenlijst Beleving en Beoordeling van de Arbeid [The Measurement of Psychosocial Job Demands with a Questionnaire (VBBA)]. Amsterdam: NIA. [Google Scholar]

- Van Yperen, Nico W., and Mariët Hagedoorn. 2003. Do high job demands increase intrinsic motivation or fatigue or both? The role of job control and job social support. Academy of Management Journal 46: 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Howe Chern, Luke Andrew Downey, and Con Stough. 2014. Understanding non-work presenteeism: Relationships between emotional intelligence, boredom, procrastination and job stress. Personality and Individual Differences 65: 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, Peter, John Cook, and Toby Wall. 1979. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Psychology 52: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, David, Lee Anna Clark, and Auke Tellegen. 1988. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 1063–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, Jason, Graham L. Bradley, and Michelle Hood. 2019. Comparing effects of active and passive procrastination: A field study of behavioral delay. Personality and Individual Differences 139: 152–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, Amy, and Jane E. Dutton. 2001. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review 26: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Siqin, Jitao Lu, Hanying Wang, Joel John Wark Montgomery, Tomasz Gorny, and Chidiebere Ogbonnaya. 2024. Excessive technology use in the post-pandemic context: How work connectivity behavior increases procrastination at work. Information Technology & People 37: 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Kyung-Hyan, and Ulrike Gretzel. 2011. Influence of personality on travel-related consumer-generated media creation. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 609–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijie, Song, Nida Gull, Muhammad Asghar, Muddassar Sarfraz, Rui Shi, and Muhammad Asim Rafique. 2022. Polychronicity, Time Perspective, and Procrastination Behavior at the Workplace: An empirical study. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology 38: 355–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, Philip G., and John N. Boyd. 1999. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference—Country | Factors of Procrastination Investigated | Sample | Study Design and Measures | Key Findings | Quality * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asio and Riego de Dios (2021)— Philippines | Age; Sex, Department; civil status; Years in service | 70 employees from a higher education institution Department: Administration-50%; Faculty-50%; Age: 21–30 years-41%; 31–40 years-21%; 41–50 years-24%; ≥ 51 years-14%; Sex: Male-59%; Female-41%; Civil Status: Single-60%; Married-34%; Others-6%; Years in Service: 1–5 years-73%; 6–10 years-16%; 11 and above-11%. | Cross-sectional design. General Procrastination Scale adapted (McCloskey 2011) | Single participants had higher tendency to procrastinate. Age was positively related to procrastination. The other factors (department, sex, and years in service) were not significantly associated with procrastination. | 60% |

| DeArmond et al. (2014)— U.S. | Workload; Psychological detachment; Fatigue | 547 U.S. residents, 70.6% women, mean age 40.8 years (SD = 11.1), mean organizational tenure 7.3 years (SD = 7.9), working at least 15 h a week in an organizational setting. | Three wave cross-sectional survey. Quantitative Workload Inventory (Spector and Jex 1998); Psychological detachment from work scale (Siegrist et al. 2004); Fatigue Scale (Chalder et al. 1993); Lay’s Procrastination Scale (Lay 1986). | Fatigue was positively related to procrastination; psychological detachment had an indirect effect (via fatigue) on procrastination, as well as a direct negative effect; workload had a significant indirect effect on procrastination. | 60% |

| De Clercq et al. (2021)— Pakistan | Perceived organizational cronyism; Leader–member exchange; Organizational disidentification | 303 employees, 19% women, mean age 33 years, mean organizational tenure 5 years, from different sectors (oil and gas, banking, telecom). | Three-wave cross-sectional design. Organizational cronyism scale (Turhan 2014); Leader–member exchange scale (Graen and Scandura 1987); Organizational disidentification scale (Kreiner and Ashforth 2004); Procrastination scale (Tuckman 1991). | Perceived organizational cronyism related positively to organizational disidentification, which was positively associated to procrastination. Organizational disidentification mediated the relationship between perceptions of organizational cronyism and procrastination. High leader–member exchange mitigates this positive indirect effect of organizational cronyism on procrastination. | 80% |

| Goroshit and Hen (2018)— Israel | Negative affect. | 236 computer professionals, 64% male, aged between 22 and 71 (M = 35.7, SD = 10). | Cross-sectional design. Online Cognition Scale (OCS, Davis et al. 2002); Decisional Procrastination Questionnaire (Mann et al. 1997); Adult Inventory of Procrastination (McCown and Johnson 1989) short form of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). | The three types of procrastination (online, general, and decisional) are positively and moderately interrelated with one another and with negative affect. | 100% |

| Göncü Köse and Metin (2018)—Turkey | Paternalistic leadership; transformational leadership; organizational citizenship behaviors; turnover intention. | 126 full-time office employees, 72% female, mean age 39.6 years (SD = 10.8), mean organizational tenure 9.3 years (SD = 9.0). | Cross-sectional design. Paternalistic Leadership Scale (Aycan 2006). Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Avolio et al. 1999); Organizational citizenship behavior scale (Podsakoff et al. 1990); Turnover intentions scale (Blau and Boal 1989); Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016). | Transformational and paternalistic leadership styles were negatively related to employees’ procrastination. The conscientiousness dimension of organizational citizenship behaviors was negatively associated with procrastination. | 60% |

| Gu et al. (2022)—China | Job responsibility; family responsibility; Emotional exhaustion. | 323 employees, 56.97% female, mean age 31.46 years (SD = 9.58); 80.19% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, mean tenure 5 (SD = 2.57). | Cross-sectional design. Job-Family Multi-Role Responsibilities Scale adapted (Ruderman et al. 2002); Maslach burnout inventory—General survey adapted (Schaufeli et al. 1996); Pure procrastination Scale (Steel 2010). | Job responsibility and family responsibility were negatively associated with procrastination. Emotional exhaustion was positively correlated with procrastination. Procrastination was highest when job-family responsibilities were in congruence (high job-high family responsibilities and low job-low family responsibilities). Emotional exhaustion mediated the effect of job-family congruence/incongruence on procrastination. | 100% |

| Gupta et al. (2012)—India | Sex; age; time perspective. | 236 employees, 141 males, mean age 28.14 years (range 21–58; SD = 7.95) from seven major information technology and financial firms. | Cross-sectional design. Lay’s (1986) workplace procrastination measure; Time perspective inventory (Zimbardo and Boyd 1999). | No significant sex differences in procrastination. Age was negatively correlated with procrastination. Procrastination was negatively related to future and to past negative time orientations and positively related to present-fatalistic and to past positive orientations. | 60% |

| Hen et al. (2021)—Israel | Decisional Procrastination General Procrastination Work Procrastination | 204 participants, 70% men, mean age 44 (SD = 10, range 20–70), 48% with college degrees, 53% mostly engage in office work and 47% work outside the office. | Cross-sectional design. Decisional Procrastination Scale (Mann 1982); Adult Inventory of Procrastination (McCown and Johnson 1991); Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016). | Decisional Procrastination and General Procrastination were positively associated with Work Procrastination. Work environment moderates these relationships: both effects are stronger for office workers. | 80% |

| Huang et al. (2022)—China | Perceived red tape Perceived overqualification Role overload | 751public employees, 54.5% male, mean age 32.51 years (SD = 10.65), 89.9% with a bachelor’s degree, 54.7% had less than seven years’ tenure, and 43% had tenures of over seven years. | Two-wave cross-sectional. Perceived red tape scale (Jacobsen and Jakobsen 2018); Perceived overqualification scale (Maynard et al. 2006); Role overload scale adapted from Schaubroeck et al. (1989) and Beehr et al. (1976); Procrastination scale (Tuckman 1991). | Perceived red tape, role overload and perceived overqualification were positively correlated with procrastination. Role overload mediated the relationship between perceived red tape and procrastination. The indirect effect of perceived red tape on procrastination via role overload is stronger when perceived overqualification is high. | 100% |

| Jones (2020)— US, China | Harmonious job passion; obsessive job passion (OJP); job satisfaction; salary level. | The US sample: 300 retail employees, 50% women, mean age 39.66 years (SD = 12.94), mean tenure 8.38 years (SD = 7.80), average annual salary US$ 44,845. The China sample 300 employees, 50% women, mean age 38.15 years (SD = 11.31), mean tenure 15.83 years (SD = 11.05); average annual salary US$ 14,913. Both income distributions represent lower middle class in their respective countries. | Cross-sectional design. Job passion (harmonious and obsessive) Scale (Vallerand et al. 2003) adapted to the retail context (Ho et al. 2011); Procrastination at work scale (Mann et al. 1997); Job satisfaction scale (Saks 1995). | Negative relationship between harmonious job passion and procrastination in both national samples. Obsessive job passion had a positive relationship with procrastination in China but a non-significant relationship in the US. Significant three-way interaction of job satisfaction–salary level–obsessive job passion in both national samples: high obsessive job passion x low salary level x low job satisfaction strengthens procrastination. | 80% |

| Kanten and Kanten (2016)— Turkey | Conscientiousness; Extraversion; Agreeableness; Neuroticism; Self-efficacy; Self-esteem. | 300 employees from four hospitals, 55% female, aged 35–49 years; 65% have been working for 2–6 years, 12% for more than 7 years, and 23% for less than 1 year in the same hospital. | Cross-sectional design. Big Five Personality Scale (Yoo and Gretzel 2011); General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995); Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg 1965); Procrastination Scale (Tuckman 1991). | In the correlational analysis, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness were negatively related to procrastination. Neuroticism was positively related to procrastination. In the multiple regression analysis, conscientiousness retained its negative effect on procrastination, and neuroticism its positive effect. Self-efficacy beliefs and self-esteem had a negative relation with procrastination. | 60% |

| Khoshouei (2017)—Iran | Job characteristics (feedback, autonomy, task significance, task identity, skill variety) locus of control (internal, external). | 193 nurses, 172 females (89.1%) aged 23 to 49 years, mean age 37.92 (SD 7.42), mean tenure 12.77 (SD 9.69). | Cross-sectional design. General procrastination scale (Lay 1986); Job cognition questionnaire; Work locus of control scale (Spector 1988). | Negative relationship between procrastination and feedback as a job characteristic. Positive relationship between procrastination and external locus of control. | 80% |

| Kühnel et al. (2022)—Germany | Study 1. Positive affect, Time pressure. Study 2. Work-related positive affect, time pressure. | Study 1. 108 self-employed and employees from companies, 46% women, mean age 41 years (SD = 10). Study 2. 154 self-employed and employees from companies, 50% women, mean age 38 years (SD = 13). | Diary study. Study 1. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule scales (Watson et al. 1988); Day-specific procrastination Tuckman’s (1991) scale adapted (Kühnel et al. 2016); Day-specific time pressure scale (Semmer et al. 1999). Study 2. Positive affect in the work domain were assessed with the three vigor items of the UWES-9 (Schaufeli et al. 2006); Day-specific procrastination (Kühnel et al. 2016; Tuckman 1991); Day-specific time pressure scale (Semmer et al. 1999). | Study 1. Negative relationship between positive affect and procrastination and between day-specific time pressure and procrastination. The negative relationship between day-specific time pressure and procrastination was moderated by positive affect, such that it is less strong for individuals with higher levels of positive affect. Study 2. Work-related positive affect (vigor) was negatively related to procrastination. Time pressure was negatively related to procrastination. Work-related positive affect was a cross-level moderator of the day-specific relationship between time pressure and procrastination. | 80% |

| Lin (2018)— China | Inclusive leadership; intrinsic motivation; perceived insider status. | 327 employees working in different industries, 167 women, aged 21 to 30 years, mean age 29.99 years; 21.1% engaged in service work, 19.9% in managerial work, 17.7% marketing work and 14.1%, in research and development work. | Cross-sectional design. Irrational Procrastination Scale (Steel 2007); Inclusive leadership (Carmeli et al. 2010); Intrinsic motivation (Van Yperen and Hagedoorn 2003) Perceived insider status (Stamper and Masterson 2002). | Inclusive leadership negatively influenced procrastination behavior, and intrinsic motivation mediated this effect. Perceived insider status moderated the relationship between intrinsic motivation and procrastination behavior. | 80% |

| Metin et al. (2016)—The Netherlands and Turkey | Study 1. Boredom at work; Counterproductive Behavior; Work engagement. Study 2. Besides the factors investigated in Study 1: Job resources (autonomy and opportunities for learning and development); Job demands (workload and mental demands). | Study 1. 384 Dutch white-collar employees, 51% male, mean age 40.1 years, (SD = 12.8), mean tenure 8.4 years (SD = 10.4). On average participants worked 32.9 h per week (SD = 10.6 h) with an average of 5 h overwork (SD = 1.1). Study 2. The Dutch sample is the same as in study 1. The Turkish sample: 243 white-collar employees, 56% female, mean age 36.3 years (SD = 10.34). On average the Turkish employees worked 8 h more than the Dutch sample (M = 41.15 h, SD = 9.70), with 6.4 h of overwork per week (SD = 8.83). | Cross-sectional design. Study 1. Dutch Boredom Scale (Reijseger et al. 2012); Counterproductive Behavior Checklist (Spector et al. 2006); Avoidance Reactions to Deadline Scale (van Eerde 2003); Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli et al. 2006); Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016). Study 2 added Job Resources and job demands (Van Veldhoven and Meijman 1994). | Study 1. Procrastination at work was positively related with general procrastination, counterproductive behavior, and boredom, and negatively associated with the subdimensions of work engagement. Study 2. Boredom was positively linked to procrastination at work and to counterproductive behavior in Dutch and Turkish samples. Procrastination at work and counterproductive behavior were positively associated in both national samples. A significant positive relationship between resources and procrastination was found in the Dutch sample. Boredom mediated the relationship between workload and procrastination at work, in the Dutch but not in the Turkish sample. | 60% |

| Metin et al. (2018)— The Netherlands | Job crafting; authenticity; work engagement; performance. | 380 white-collar full-time employees, 50% men, mean age 42.1 years (SD = 12.4), mean tenure 11.6 (SD = 10.9) years. On an average, respondents reported they worked 33.9 h (SD = 7.1) per week, with an average of 4 h of overwork per week. | Cross-sectional design. Job crafting questionnaire (Petrou et al. 2012); Individual Authenticity Measure at Work (Van den Bosch and Taris 2014a); Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli and Bakker 2003); Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016); Individual Work Performance Questionnaire (Koopmans et al. 2012). | Work engagement was negatively linked to procrastination. Performance and procrastination were negatively related. No mediation was found for the indirect path from job crafting and authenticity to procrastination via work engagement. | 60% |

| Moharram-Nejadifard et al. (2020)—Iran | Cognitive behavioral therapy mainly aiming to develop participants’ self-esteem and their abilities to regulate negative emotions and tolerate disturbances. | 21 participants in the cognitive behavioral treatment group, 20 in the control group, all midwives working in public and private hospitals, mean age 31.52 (SD 5.82) and 35.75 (SD 8.04) years, mean work experience 7.43 (SD 5.21) and 11.24 (SD 7.96) years. | Experimental study. Tuckman procrastination scale (TPS, Tuckman 1991); Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995); Decisional Procrastination Scale (Mann 1982) Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016). | Cognitive behavioral group therapy is significantly associated with the diminishments in workplace procrastination, soldiering, cyberslacking, and decisional procrastination, respectively. | 100% |

| Mosquera et al. (2022)—Portugal | Boredom at work; work stress; job satisfaction. | 287 participants, 94 males, mean age 34.5 years (SD = 11.97), 78.3% had a bachelor’s degree or above. | Cross-sectional design. Boredom at work scale (Reijseger et al. 2012). Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016). | Boredom at work increases cyberslacking and soldiering. | 60% |

| Nguyen et al. (2013)—US | Job characteristics; employment status; income; gender; age. | 22,053 individuals, 44.9% males, 7.8% unemployed, 15.1% working part-time, 77% working full-time, Annual income: Less than $10,000 = 18.4%; $10,000 to $20,000 = 9.7%; $20,000 to $30,000 = 9.1%; $30,000 to $40,000 = 8.8%; $40,000 to $50,000 = 8.9%; $50,000 to $60,000 = 8.3%; $60,000 to $75,000 = 9.2%; $75,000 to $100,000 = 10.8%; $100,000 to $200,000 = 12.7%; $200,000+ = 4.2%. | Cross-sectional design. Irrational Procrastination Scale (Steel 2010); Using respondents’ open-ended job descriptions, two authors independently linked occupations with O*NET job codes and then to the job characteristics required for the assessment, including work value, work style, occupational interest, and constraint, using the protocol proposed by Meyer et al. (2009). | Procrastination is associated with lower income. Gender moderates the relationship between procrastination and income such that it is stronger for men than women. Procrastination is associated with a reduced period of employment. Procrastinators are more likely to be unemployed than working full-time, and, if working, working part-time rather than full-time. Procrastination is negatively correlated with work values. Procrastination is negatively correlated with investigative occupations. Procrastination is negatively correlated with achievement/effort, social influence, adjustment and conscientiousness. Procrastination is positively associated with constraint. | 60% |

| Pearlman-Avnion and Zibenberg (2018)—Israel | Agreeableness; Conscientiousness; neuroticism; dis-regulation of anxiety. | 107 Israeli employees, 80% working full-time, 62.7% women, mean age 45.11 years (SD = 10.24). | Cross-sectional design. Lay’s (1986) Procrastination Scale Big Five Inventory (John and Srivastava 1999); Dis-regulation of anxiety scale (Assor et al. 2009). | Conscientiousness and agreeableness are negatively associated with procrastination. Neuroticism is positively associated with procrastination. Among participants with low dis-regulation of anxiety, there was a positive relationship between agreeableness and procrastination, but among the participants with high dis-regulation of anxiety, there was a negative relationship between agreeableness and procrastination. Among the employees with high dis-regulation of anxiety, there was a stronger relationship between conscientiousness and procrastination, compared to those with low dis-regulation of anxiety. | 80% |

| Prem et al. (2018)— Germany | Problem solving; Time pressure; Planning and decision-making; Challenge appraisal; Hindrance appraisal; Self-regulation effort. | 110 employees, 77.3% females, mean age 35.1 years (SD = 10.0). | Diary study design. Work Design Questionnaire (Morgeson and Humphrey 2006). The instrument for stress-oriented job analysis adapted (Semmer et al. 1999). Intensification of Job Demands Scale (Kubicek et al. 2015); Challenge appraisal, Hindrance appraisal (Searle and Auton 2015); Self-control demands Questionnaire adapted (Schmidt and Neubach 2010); Workplace procrastination (Tuckman 1991). | Day-level work characteristics, i.e., (a) time pressure, (b) problem solving, and (c) planning and decision making, have a negative serial indirect effect on daily workplace procrastination via increased challenge appraisal and consequently reduced self-regulation effort. Time pressure also has a positive serial indirect effect on daily workplace procrastination via increased hindrance appraisal and consequently increased self-regulation effort. | 80% |

| Sharma and Sharma (2021)—India | Work-life balance. | 104 office employees, 63 males, aged 27 to 44 years. | Cross-sectional design. Procrastination Scale (Lay 1986); Work-life balance scale (Pareek et al. 2011). | Work-life balance was negatively correlated with procrastination. | 60% |

| Shaw and Choi (2022)—US | Conscientiousness; Emotional Stability; Extraversion; Openness to Experience; Agreeableness. | 173 white-collar corporate employees in lower-to-middle level positions, mean age 29.05 (SD = 2.82 years, 52% male, in their current job for over a year, most of them had worked with the current supervisor for approximately one year. | Cross-sectional design. Supervisor-reported personality traits of the employees and employees self-rated personality traits using the International Personality Item Pool scale (Goldberg et al. 2006); Active procrastination scale (Choi and Moran 2009). | Extraversion and emotional stability positively predicted active procrastination across both rating sources. In the supervisor-rating results only, agreeableness emerged as another (negative) predictor of active procrastination. | 60% |

| Singh et al. (2021)—India | Management by exception passive leadership; Laissez-faire style of leadership. | 268 men, middle-level textile managers; Age: 25–30 years = 58 (21.6%); 30–35 years = 166 (61.9%); 35–40 years = 35 (13.1%); 40–45 years = 9 (3.4%). Experience (years) <5 = 88 (32.8%) 5–10 = 144 (53.7%) 10–15 = 28 (10.4%) >15 = 8 (3%) | Cross-sectional design. Irrational Procrastination Scale (Steel 2010); Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Avolio and Bass 2004). | Management by exception passive leadership style is a positive predictor of perceived procrastination in leaders. Laissez-faire style of leadership increases perceived procrastination in leaders. Laissez-faire style of leadership does not moderate the relationship between management by exception passive style of leadership and perceived procrastination in leaders. | 60% |

| Singh and Bala (2020)—India | Conscientiousness; Self-efficacy. | 255 textile managers/executives, all men, mean age 32.5 (SD 6.4), mean work experience 6.5 (SD 1.80). | Cross-sectional design. Personality inventory (John and Srivastava 1999); Irrational procrastination scale (Steel 2010); General self-efficacy scale (Romppel et al. 2013). | Self-efficacy and conscientiousness have negative relationships with procrastination. Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between conscientiousness and procrastination. Conscientiousness also has a direct effect on procrastination. | 60% |

| Šuvak-Martinović and Zovko (2017)—Bosnia and Herzegovina | Gender; Age; Type of employment; Civil status; Presence of children; Job demand-control; Self-Efficacy; Depression; Anxiety. | 70 teaching assistants, 46 employed full time, 44 women, mean age 30.22 years (SD = 1.87), 29 married, 19 had children. | Cross-sectional design. The Avoidance Reactions to a Deadline Scale (van Eerde 2003); The Job Demand-Control Scale (Gregov and Šimunić 2012); General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer et al. 1997; adapted by Ivanov 2002); Lovibond’s Depression Anxiety Stress Scale adapted (Reić Ercegovac and Penezić 2012). | No significant differences in procrastination according to gender, age, type of employment, civil status, or presence of children. In the bivariate correlation analysis, job demands, depression and anxiety symptoms were positively associated with procrastination, while perceived job control and general self-efficacy were negatively related to procrastination. In the multiple regression analysis, the only significant predictor of procrastination was perceived job control, while self-efficacy, depression and anxiety and job demands were not significant predictors. | 60% |

| Tandon et al. (2021)—US | Exhibitionism; Voyeurism; Fear of Missing Out; Compulsive use of social media. | 312 full time employees, 51.3% male, 48.7% females, age: 25–34 years 60.3%; 35–44 years 24.4%; 45–54 years 15.4%; Total work experience 1–3 years 9.0%; 3–5 years 9.0%; 5–7 years 10.6%; 7–9 years 10.9%; >9 years 60.6%. | Cross-sectional design. CB-SEM, Path analysis Exhibitionism Scale (Mäntymäki and Islam 2016); Voyeurism Scale (Mäntymäki and Islam 2016); Fear of Missing Out (Przybylski et al. 2013); Compulsive use of social media (Andreassen et al. 2012); Work performance decrement (Cao et al. 2016; Kuvaas 2006); Procrastination due to social media use at work adapted by Tandon et al. (2021). | Individual tendencies of exhibitionism and voyeurism act as stressors and strain the individual’s psychological state, represented by Fear of missing out, which translates into adverse psychological (Compulsive use of social media) and behavioral (procrastination and work performance decrement) outcomes. | 80% |

| Tudose and Pavalache-Ilie (2021)—Romania | Age; Gender; Work satisfaction. | 109 employees from public and private sector, 71 women, mean age 33.58 (SD = 7.56) | Cross-sectional design. Job satisfaction scale (Warr et al. 1979); Procrastination at Work Scale (Metin et al. 2016). | No significant association between employee satisfaction and procrastination at work. Men had higher scores on the cyberslacking subscale of the procrastination measure compared to women. The youngest employees (18–25) years scored higher than those in the 45–55 age group on procrastination. | 60% |

| Uysal and Yilmaz (2020)—Turkey | Hierarchical career plateau. | 367 employees, 49.6% male, 81.8% aged 21 to 40 years, 67.3% university graduates, 89.9% with more than 1 year of work experience. | Cross-sectional design. Hierarchical career plateau scale adapted (Allen et al. 1999); Procrastination Scale (Lay 1986). | Positive correlation between the hierarchical career plateau and workplace procrastination. Workplace procrastination did not vary depending on work experience, monthly income, age or gender. | 60% |

| van Eerde (2003)—The Netherlands | Time management; worry; Peer ratings of orderliness. | 37 employees in the treatment group and 14 in the control group, 75% men, mean age 37 years, 75% with a college degree, average age was 37, average tenure 5.9 years. | Quasi-experimental study. Berkeley Personality Profile (Harary and Donahue 1994); Time Management Behavior Scale (Macan 1994); VBBA (Van Veldhoven and Meijman 1994); Avoidance reactions (van Eerde 1998); Peer ratings of employee orderliness. | The time management intervention increased time management behavior in the treatment group, while no change was found in the control group. The treatment group also reported a decrease in worrying whereas the control group did not report any change. The avoidance reactions (procrastination) of the treatment group decreased, whereas avoidance reactions in the control group remained stable. Peer ratings of orderliness were correlated negatively with procrastination. | 60% |

| Wan et al. (2014)—Australia | Boredom; job stress; non-work related presenteeism; emotional intelligence. | 184 employees, 57 males aged from 23 to 61 years (M = 38.61, SD = 1.36), and 127 females aged from 22 to 67 years (M = 40.99, SD = 1.02). | Cross-sectional design. Genos EI Inventory Scale (Gignac 2010); Procrastination scale (Tuckman 1991); Boredom Proneness Scale; (Farmer and Sundberg 1986); Role Stress Measures (Beehr et al. 1976); Engaging in personal activities while at work (D’Abate and Eddy 2007). | Non-work related presenteeism is positively related to procrastination. Emotional intelligence is negatively related to procrastination. There are positive relationships between job stress and procrastination, and between procrastination and boredom. No significant difference between females and males on all five outcome measures (including procrastination). | 60% |

| Category of study designs | Author, year, country | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Is randomization appropriately performed? | Are the groups comparable at baseline? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? |

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | Moharram-Nejadifard et al. (2020). Iran | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Category of study designs | Author, year, country | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Are the participants representative of the target population | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure) | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? |

| Non-randomized controlled trials | van Eerde (2003) The Netherlands | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Asio and Riego de Dios (2021) Philippines | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | DeArmond et al. (2014) U.S. | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | De Clercq et al. (2021) Pakistan | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Göncü Köse and Metin (2018) Turkey | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Goroshit and Hen (2018) Israel | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Gu et al. (2022) China | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Gupta et al. (2012) India | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Hen et al. (2021) Israel | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Huang et al. (2022) China | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Jones (2020) US, China | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Kanten and Kanten (2016) Turkey | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Khoshouei (2017) Iran | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Lin (2018) China | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Metin et al. (2018) The Netherlands | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Metin et al. (2016). Study 1 The Netherlands | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Metin et al. (2016). Study 2 The Netherlands, Turkey | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Mosquera et al. (2022) Portugal | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Nguyen et al. (2013) US | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Pearlman-Avnion and Zibenberg (2018) Israel | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Sharma and Sharma (2021) India | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Shaw and Choi (2022) US | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Singh et al. (2021) India | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Singh and Bala (2020) India | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Šuvak-Martinović and Zovko (2017) Bosnia and Herzegovina | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Tandon et al. (2021) US | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Tudose and Pavalache-Ilie (2021) Romania | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Uysal and Yilmaz (2020) Turkey | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Cross-sectional | Wan et al. (2014) Australia | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Diary | Kühnel et al. (2022) study 1 Germany | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Diary | Kühnel et al. (2022) study 2 Germany | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Diary | Prem et al. (2018) Germany | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musteață, I.; Holman, A.C. Factors of Workplace Procrastination: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060380

Musteață I, Holman AC. Factors of Workplace Procrastination: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):380. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060380

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusteață, Iraida, and Andrei Corneliu Holman. 2025. "Factors of Workplace Procrastination: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060380

APA StyleMusteață, I., & Holman, A. C. (2025). Factors of Workplace Procrastination: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 14(6), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060380