Abstract

Profound changes in trade policymaking are taking place in the 2020s in response to a complex set of increasingly salient risks shaping the international trade system. Drawing upon the influential theory of risk society, this study develops a new trade risk society framework providing original insights and new conceptual thinking on the subject. This analytical approach extends beyond merely a topical evaluation of current risks to one embedding trade in deeper underlying developments in our contemporary world and challenges facing it. Key elements of risk society theory are deployed to this end across four risk domains: 1. Economic security. 2. Geopolitical volatility. 3. Climate–environmental. 4. Technology control. Close interconnections exist between these domains, as shown in the framework’s applied analysis of the 30 or so most significant trade policymaking initiatives introduced thus far this decade up to and including US President Trump’s aggressive tariff protectionism. It is argued this pattern of initiatives are indicative of a paradigm shift in trade policy norms emerging in an increasingly volatile and contested world that can be best understood in a trade risk society context.

1. Trade: Disrupted… and at Risk

International trade has experienced numerous profound shocks and disruptions in the 2020s. The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia–Ukraine war have created critical supply shortages and price hikes in key commodities such as energy and food. Maritime shipping of traded goods has been interrupted by attacks in conflict zones. Intensifying geopolitical volatility—especially the systemic rivalry between the United States and China—is causing substantial friction in trade relations. Globalisation is no longer the undisputed primary driving force of world order and on many fronts is in retreat (WEF 2024, 2025). The annual number of restrictive trade measures globally has risen from 600 in 2017 to over 3000 from 2022 to 2024 (Global Trade Alert 2025), and global trade has contracted (UNCTAD 2024). Countries are competing more intensely to establish control positions in various frontier technology industries such as artificial intelligence and clean energy through new trade–industrial policies. This includes a scramble for critical mineral resources on which these industries depend. The impacts of climate change and other environmental issues on trade are meanwhile increasingly evident. For example, a succession of severe droughts significantly limited trade passing through the Panama Canal for lengthy periods in 2023 and 2024. In 2025, Donald Trump began his second US presidential term with a reinvigorated tariff protectionist policy that presents major risks for the world trade order.

This study examines the impacts of the above factors on trade policymaking and shows empirically how significant new trade policy norms have consequently emerged this decade. But how can we make sense of this major development within a unified analytical framework? This study offers a solution to this puzzle through understanding those impacts as a complex set of interconnected and increasingly salient risks shaping trade policy in new profound ways. Drawing upon the influential theory of risk society (Beck 1992, 2008, 2015), a new trade risk society (TRS) framework is presented to better understand this paradigm shift in trade policymaking taking place in the 2020s. The next section presents the TRS framework’s core elements, first outlining risk society theory and its links with trade. These elements also commonly underpin the framework’s more empirically specific analytical functions centre on four ‘risk domains’, namely the following: 1. Economic security risk. 2. Geopolitical volatility risk. 3. Climate–environmental risk. and 4. Technology control risk. In each risk domain section, the TRS framework is further conceptually developed and then empirically applied to the 30 or so most significant trade policymaking initiatives thus far introduced this decade by the world’s major trade powers and middle-ranking trade nations (Table 1). Given that these powers and nations collectively account for around 80 percent of world trade, these initiatives provide the evidential basis for the trade risk society turn in trade policymaking. The study thus combines broad empirics with new conceptual thinking, offering original insights and understandings on this critically important subject.

Table 1.

Major new trade policymaking initiatives in the 2020s.

2. Trade Risk Society

2.1. Risk Society Theory and Trade

International trade has long associations with risk. Undertaking commercial transactions between distant countries with often very different cultural, political, and legal–regulatory systems can be hazardous. The historic origins of the global insurance industry are closely connected with the management of international trade risk (Boudia and Jas 2007). Risk analysis is also applicable to trading activity where certain technical risks to human health, animal welfare, or the environment are pertinent (Adamchick and Perez 2020). In the social sciences, Ulrich Beck’s (1992) influential theory of risk society offers a wider meta-level analysis of risks in our contemporary world. Despite still being widely used today in various research fields (e.g., Kesselring 2024; Lidskog and Zinn 2024; Sovacool 2025; Sundberg 2024), risk society has very rarely if at all been applied to international trade. This study addresses this gap by developing a new analytical framework of trade risk society.

Beck (1992, p. 21) defined risk society as essentially ‘a systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities induced and introduced by modernisation itself’. The theory centres on the broad impacts of modernisation and industrialisation on social and natural environments and how the pace and scale of transformative change has created a social order significantly more dynamic than anything previously experienced. The contemporary world had furthermore transitioned from a ‘industrial society’ to a ‘risk society’ during the latter half of the 20th century as a consequence of ‘an inescapable structural condition of advanced industrialisation’ and that ‘Modern society has become a risk society in the sense that it is increasingly occupied with debating, preventing and managing risks that it itself has produced’ (Beck 1995, p. 65). Certain risks arising from these processes pose existential threats to human civilisation, including how burgeoning industrialisation is critical endangering of the biosphere. These human ‘manufactured risks’ were de-bounded in temporal, spatial, and social terms, transcending national boundaries and frequently global in scale (Denney 2005; Lupton 1999; Taylor-Gooby and Zinn 2006). Their levels of threat can furthermore be generally subject to cyclical patterns (e.g., geopolitical volatility), incidental spikes (e.g., nuclear disasters), or gradual intensification, such as the long crisis of climate change. Particular risks may escalate very quickly with global-scale transmission effects, such as COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s.

Reflexive modernity is a core risk society concept, referring to how societies engage in constant evaluations of existing and future potential risks, thus regularly reviewing the efficacy of current practices to deal with those risks and undertake new courses of action. Beck (1996, 2008) contended that reflexive modernity accordingly involved the changing social construction of risks in response to evolving priorities, events, and dominant discourses that shape them. Consequently, reflexive modernity frames the continual turnover of new risk aversion policies implemented by governments on behalf of an ‘at risk’ society (Boudia and Jas 2007; Lidskog and Zinn 2024). There may be occasions, though, when certain risk aversion policies contradict or undermine others, or later exacerbate other types of risk (Giddens 1990), for example, where the pursuit of economic growth to maintain stability in global capitalist system causes longer-run environmental instabilities.

Risk society theory has been criticised for at times blurring distinctions between different types of risk and often overlooking factors of class, ethnicity, gender, and nationality, as well as insensitivity to cultural, geographic, and historical differences existing in different localities worldwide (Denney 2005; Lupton 1999; Mythen 2021). For example, Beck’s increasing use of ‘world’ risk society suggests notions of universal experience of hazards and threats incommensurate with reality, where the global distribution of harms (e.g., famine, warfare) is clearly uneven and unequal (Mythen et al. 2018). Yet this does not exclude risk society’s application to international or global systems, where risks have systemic attributes or in some way help define systems at this level. For others, the theory’s inadequate differentiation of types or domains of risk is a weakness of Beck’s core ideas, as well as tending to frame risks often in ‘catastrophic’ terms with limited level gradation (Curran 2013).

Additionally, risk society has been critiqued for frequently lacking sufficient empirical validation (Dryzek 1995; Marshall 1999; Taylor-Gooby and Zinn 2006) or for being far more concerned with analysing the symptoms of risk society than how to treat its associated ills and its impact on policymaking and policy-based solutions (Baumann 1997; Lacy 2002). This criticism, though, would seem to overlook the key functional role played by Beck’s reflexive modernity in explaining dynamic policymaking responses to risk society challenges. Although Beck incorporated social, political, cultural, economic, science–technological, and other disciplinary themes into his thinking, empirical evidence used to support his claims were often unstructured and lacking systemic organisation. Beck (2008) did consider economic risks as a distinct risk type, defined principally by outcomes generated by the systemic interconnections and asymmetric patterns of globalisation. Yet he was essentially a social theorist, and the analytical thrust of his own approach was primarily sociological. Where acknowledged, trade is only referenced extremely briefly with regard to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and strengthening governance structures to manage global economic crises (Beck and Grande 2010; Mythen 2021). To summarise, there has hitherto been no substantive application of risk society theory to trade. In addition, filling this particular gap, the study also looks to address many of the above other criticisms of the theory, for example, by elaborating on differentiated but interconnected risk domains.

2.2. Towards a Trade Risk Society

This section presents the core elements of trade risk society. The framework’s grounding in risk society theory transcends mere observations of current risks affecting international trade to an analysis that embeds trade in deeper underlying developments in our contemporary world and challenges facing it. Trade is a well acknowledged fundamental driver of both modern industrialisation and globalisation. The systemic interconnections and economic interdependencies forged by trade through various market, regulatory, technological, corporate, and other forces have brought both benefits but also new global-scale ‘manufactured’ risks. The 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis revealed how, in deeply integrated trading systems, a disruptive event occurring in one location can quickly become a worldwide contagion. Trade has furthermore been significantly instrumental in creating various asymmetric patterns of globalisation. These in turn have generated risks associated with exploiting dominant positions in uneven trading relationships, as well as from divergent income gaps between and within countries (Rodrik 2021). While contemporary developments in the international trade system have mitigated certain risks (e.g., mutualised economic interests leading to conflict aversion), it has recently shown to lack resilience in key areas when subjected to notable disruptive events and developments. The generally inert WTO in recent years is furthermore indicative of critical weaknesses in global trade governance. In the 2020s, trade policymakers are making decisions in response to revealed underlying risks in an increasingly ungoverned and anarchic global trade system.

Reflexive modernity has consequently become more relevant to trade policymaking, needing to adapt more quickly and effectively in response to new emergent risks and their disruption of international trade. This was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic where despite the deep contraction in world trade, governments engaged in highly dynamic trade policymaking processes and a subsequent spike in both trade-facilitating and trade-restricting measures (Evenett 2022; Global Trade Alert 2025). In turn, this fostered new norms on state commercial policy interventions in a reflexive modernity context. Many have formed around numerous trade–industrial policies introduced in the early 2020s that generally reflect the transnational organisation of production in most key industries based on often complex ecosystems of supply chain trade relationships. The global economy is founded on such trade–industrial systems that have led to around 40 percent of world trade comprising cross-border exchange of parts and components (WTO 2022).

In addition, reflexive modernity has relevance to the social construction of new and evolving risks in the trade system. This idea is conceptually developed and applied in the four empirical domain sections that follow, as well as the concept of derisking that has become highly influential in trade policymaking in the 2020s. Derisking generally refers to proactively managing risk in maintained trade relationships, identifying where key threats exist within them in order to strengthen economic resilience and reduce critical trade-related vulnerabilities (Roberts 2023). This is often differentiated from the linked concept of decoupling trade from ‘untrusted’ partners, involving government attempts to deconstruct trade relationships through adopting restrictive measures aimed at blocking most commercial interactions. Derisking is thus a relatively more positive approach leading to recent trade policy innovation, such as hybrid trade agreements and new trade–industrial strategies.

While conventional grand theories of international political economy can offer their own particular perspectives on the subject matter, the TRS framework provides new thinking and understanding of trade policymaking in the 2020s and possibly beyond. Moreover, we later explored that the trade risk society approach also brings together certain elements of those conventional theories in a new unified way. For example, neorealist explanations of great power rivalries driving geopolitical volatility and relatedly more assertive trade policies where states are seeking to gain competitive advantages over others whether through trade–industrial strategies or tariff protectionism. Although neoliberalism claims that non-state actors—such as later discussed powerful tech-firms—can be influential players in international economic relations, trade risk society helps explain why liberal norms of market openness are in retreat in trade policymaking in the 2020s due mainly to a lack of trust in market forces to address extant risks. The application of reflexive modernity within the TRS framework to understanding the dynamic social construction of new and evolving risks in the trade system was earlier noted, thus with links to constructivism theory. The framework also accommodates ideas on how trade policy has recently become more functionally multipurpose in both objective and nature, hence connecting with associated concerns arising in critical theories of international political economy such as labour and environment (Lamp 2023; Lydgate 2022).

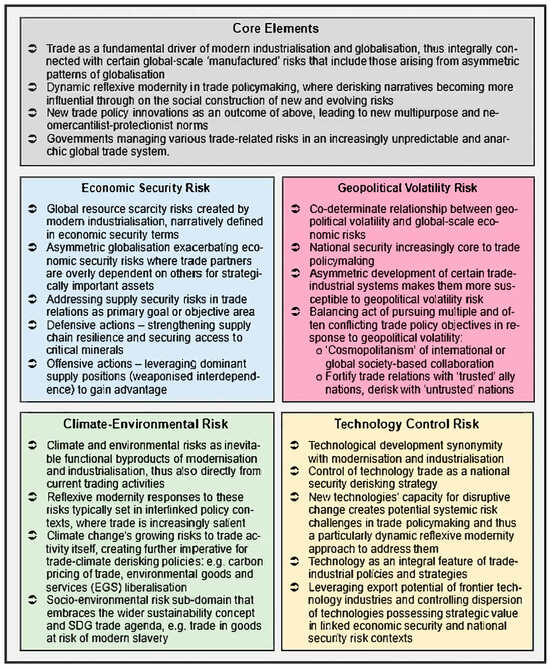

The following sections develop the TRS framework’s more empirically specific analytical functions, centred on four risk domains: economic security, geopolitical volatility, climate–environmental, and technology control. Thematically, they generally define and frame trade’s connections with fundamental ‘risk’ challenges facing our contemporary world. The choice of these four domains thus derives from empirical observations of recent trends in trade policymaking among the major and middle-ranking trade powers from different but connected risk analysis perspectives. Theorisation and building a conceptual framework like the TRS furthermore requires some degree of creative generalisation when trying to capture, categorise, and explain empirical reality, whilst simultaneously deriving from that same observed reality. These four empirical risk domains were developed from this methodological process. As is explored, interconnections exist between the domains, but each provides its own useful conceptual lens through which trade risk society can be viewed and trade policymaking in the 2020s better understood. The framework brings them integrally together, as summarised in Figure 1. The 30 or so most important trade policymaking initiatives worldwide introduced in the 2020s to date are outlined in Table 1 and provide the main empirical basis of this study. As indicated, the majority have multiple risk domain aspects, with the most important placed top in this column and this determining in which section the initiative is primarily discussed.

Figure 1.

Trade risk society: An analytical framework.

3. Economic Security Risk

Risk society theory posits that mass production and consumption systems arising from modern industrialisation have created global resource scarcity risks (Beck 2008; Boudia and Jas 2007; Mythen 2021). In the 2020s, this risk became narratively defined in economic security terms in particular with trade a core focus. Relatedly, asymmetric globalisation is viewed as exacerbating economic security risks where trade partners had become overly dependent on others for strategically important materials, technologies, components, and other assets. Countries seeking to dominate the global supply chains of certain industries can cause similar economic security risk predicaments. More generally for this decade, economic security is concerned with mitigating various supply security risks in trade relations caused by a combination of recent disruptive events and longer-term developments in many trade–industrial systems, most notably the following:

- ⮊

- Shortening supply of critical minerals as demand for them accelerates in frontier technology industries such as clean energy, advanced semiconductors, and digital infrastructures.

- ⮊

- COVID-19 pandemic disruptions to international supply chains generally and production of critical components, e.g., semiconductors.

- ⮊

- China’s growing dominance across supply chains in frontier technology industries, such as electric vehicles (EVs), solar energy, and batteries.

- ⮊

- Russia–Ukraine war and disruptions to energy, food, and other good supplies.

New trade policymaking initiatives were introduced to manage or derisk the above that could be broadly viewed in defensive and offensive attribute terms. Defensive actions on economic security risk in the 2020s have centred on strengthening supply chain resilience by adopting a dualistic approach of ‘friendshoring’ (strengthening trade with ‘trusted’ countries offering secure sources of supply) and ‘homeshoring’ (incentivising foreign-to-domestic relocation of trade-related production) in various key industries. This has involved a fusion of trade and industrial policy measures, including those to strengthen domestic markets and industries and mitigating their exposure to turbulent international forces. Consequently, trade–industrial policy initiatives have formed that combine import substitution and export production goals. Close interconnections here exist with geopolitical volatility risk, not least regarding how national security imperatives have lately become more salient in trade policymaking (Cao et al. 2023; Drinhausen and Legarda 2022).

Offensive trade policymaking actions on economic security involves trade partners leveraging dominant positions to achieve supply or industrial advantages over trade rivals in a neorealist-oriented rivalry context but with heightened risk implications. Farrell and Newman’s (2019) concept of ‘weaponised interdependence’ is highly relevant here. They argue that asymmetric developments in international trade relations can create structural power imbalances that benefit those in dominant hub positions. Export controls on strategic assets are commonly used instruments here. Whereas neoliberal interdependence theory emphasises how globalised trade and production interlinkages create imperatives for mutual cooperation from which each mutually gains (Keohane and Nye 1973), weaponised interdependence focuses on how often pronounced asymmetries within these linkages can be exploited for national economic gain. The extent to which trade interdependencies can be politico-diplomatically weaponised depends on how far state governments can exert their authority and levers of control over companies, thus a question of state–business agency (Gjesvik 2023; Nye 2020; Oatley 2021). Offensive approaches on mitigating economic security risks can involve other issues and actions, as discussed below.

New trade policymaking initiatives overtly addressing economic security risk have taken many forms. Among the most impactful and comprehensive is the EU Economic Security Strategy, launched in June 2023 and focused on ‘minimising risks arising from certain economic flows in the context of increased geopolitical tensions and accelerated technological shifts, while preserving maximum levels of economic openness and dynamism’ (European Commission 2023, p. 1). This (de)risk narrative is prevalent through the whole EU Economic Security Strategy document1 that is based on the following four main risk themes: 1. Resilience of supply chains, including energy security. 2. Physical and cyber security of critical infrastructure. 3. Technology security and technology leakage. 4. Weaponisation of economic dependencies or economic coercion. It also adopts the later discussed ‘open strategic autonomy’ principle underpinning the EU’s 2021 New Trade Strategy, gearing its economic security priorities around core trade policymaking objectives (Table 1).

The 2023 EU Economic Security Strategy comprised both defensive and offensive measures that frame the European Union’s new derisking approach to international economic relations, trade policy being pivotal. While acknowledging how the EU has long benefitted from an open, rule-based global trade regime—and that Europe cannot achieve economic security working in insolation of others—the Strategy cites the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia–Ukraine war, and escalating geopolitical volatility risk as reasons for developing a new set of policy tools to safeguard its economic interests. This included offensive mechanisms such as the EU’s dual-use export controls regulation revised in 2021. Signing new trade agreements ‘with countries on similar derisking paths’ (European Commission 2023, p. 4) meanwhile represent defensive elements of the EU’s Strategy. Here, free trade agreements (FTAs) continue to have ‘friendshoring’ utility, but alongside new trade policymaking innovations largely motivated by supply security interests, including Digital Partnerships, Green Alliances and Partnerships, and Raw Materials Partnerships.

Economic security was the headline theme at the May 2023 G7 Summit in Hiroshima. A year earlier, Japan’s 2022 Economic Security Protection Act became law with its core goal of strengthening the country’s national security through ‘integrated economic measures’, these mainly comprising trade policymaking initiatives (Table 1). In the Act’s first theme on ensuring stable supplies of critical materials, Japanese businesses involved in international supply chain trade of 11 targeted sectors were obliged to submit plans on their diversification of sources and stockpiling goods to qualify for government financial support (Japanese Government 2022). Elsewhere, South Korea introduced a technology-oriented economic security strategy in October 2022, and in March 2023, economic security was a priority objective of the UK’s Integrated Review Refresh of its foreign policy (Benson and Mouradian 2023). The UK’s new Labour Government is expected to make economic security a core theme of trade policy in accordance with its ‘National Securonomics’ strategy (Labour Party 2023).

Under President Biden (2021–2024), the US introduced mostly defensive economic security measures, such as the later discussed CHIPs Act, Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), with a common focus on trade supply chain resilience (Gerstein and Ligor 2023). His successor Donald Trump on taking office again in January 2025 initiated a mainly offensive economic security approach but centred on weaponising tariffs in a somewhat incoherent endeavour that seemed to ignore trade interdependencies and supply chain relationships (e.g., North America’s highly integrated automotive industry) or sought to dismantle them. This represented a further shift from neoliberal to neorealist thinking in US trade policymaking. The intent of the Trump 2.0 presidency was to raise and more widely apply import duties than implemented during his previous term to realise certain economic security objectives in the pursuit of ‘Making America Great Again’. Leveraging its pivotal position in the international trade system, it was hoped aggressive protectionism would induce foreign firms to relocate operations to the US behind its high tariff walls and boost national industrial production, this including supply chain capture. Thus, this policy also had defensive ‘homeshoring’ attributes. With the same goal, Trump had also threatened punitive tariffs (at 200 percent) on American companies such as John Deere planning to move production to Mexico then export back to the US.2 Given that two-thirds of US imports of goods comprises parts and components in supply chain trade directed to domestic production, this decoupling strategy could have major inflationary effects and consequently make US-made products less price competitive.3

Trump’s aggressive tariff protectionism also posed further economic security risks to other nations and the global trading system generally. Early targeted trade partners were Canada, Mexico, China, and the EU, all with significant trade volumes with the US.4 New tariffs were first applied on China in early February 2025 and threatened on the other three and then applied the following month. By this time, China had introduced retaliatory tariff and non-tariff measures on targeted US imports, with the EU, Canada, and Mexico soon also taking retaliatory action.5 Also in March 2025, the US started to apply sector-specific tariffs on steel, aluminium, and automobiles.6 Further chaos and disorder was caused by President Trump’s so called ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcements on 2 April 2025 where new high tariff rates were applied to most of the US’ main trade partners, for example, the EU (20%), China (34%), Taiwan (36%), Japan (24%), India (26%), South Korea (25%), Thailand (36%), Vietnam (46%), and Indonesia (32%). A flat 10% universal tariff was levied on all other countries, regardless of whether the US enjoyed a goods trade surplus with them.7 As a negotiating ploy, the Trump administration declared a few days later a 90-day reprieve in tariff implementation would take affect with the exception of China, leading to a dramatic retaliatory tariff escalation between the two major trade powers.8 This can conclude was a neorealist, zero-sum approach to economic security risk, eschewing all forms of collective action in the pursuit of ‘US won’ trade deals that served wider goal of American re-industrialisation.

Furthermore, President Trump’s revealed ambitions to acquire Greenland and the Panama Canal for US economic security interests in the very first week of Trump 2.0 presidency caused further alarm internationally. Securing control of Greenland’s vast untapped natural resources (critical minerals and hydrocarbons) and the strategically vital US trade route through Panama were the primary motives.9 Ukraine was also subject to Trump’s assertive economic security diplomacy in early 2025 when he made continued US support to the embattled country contingent on privileged access to its critical mineral deposits, an agreement on this brokered in April that year.10 Additional examples of where small economies and developing nations that are at economic security risk from Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ agenda also extend to the aforementioned ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs, where many of the highest rates were imposed by the countries experiencing extreme poverty and lack of development capacity, such as Lesotho (50%), Cambodia (49%), Laos (48%), Madagascar (47%), Sri Lanka (44%), Syria (41%), and Reunion Island (37%). Most had beforehand enjoyed free market access to the US under generalised system of preference terms. The subsequent application of high tariffs on these already fragile economies whilst the Trump administration was significantly scaling back of US Agency for International Development programmes was a dual blow to their economic security. The grab for overseas land and resources in the pursuit of national economic security interests—viewing developing countries more as subservient to those interests—is reminiscent of 19th century imperialism, and thereby also classic great power neorealist behaviour.

China’s approach towards economic security risk focused on two major trade policymaking initiatives launched in early 2020s (Table 1). The Dual Circulation Strategy (DCS) introduced in May 2020 is based on domestic market (internal) and international market (external) circulations. Coinciding with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it concentrated initially on fostering greater economic self-reliance during a time of heavily contracting international trade. The DCS could thus be considered an early trade decoupling or derisking ploy when Chinese exporters’ access to foreign markets became less predictable, thus strengthening domestic economic security. It was also aligned with simultaneously operationalised sector-based policies on developing China’s indigenous techno-innovation capacity (including export production in frontier technology sectors) and its domestic market (including import substitution measures) as engines of economic growth (Drinhausen and Legarda 2022). The following year, in September 2021, the government launched its Global Development Initiative (GDI) that while running alongside the incumbent Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, from 2013), is expected to eventually supersede it11, possessing similar objectives on securing strategic economic assets through China’s model of trade infrastructure diplomacy (Wu 2023). More specifically, the GDI comprises measures to improve supply chain resilience for Chinese enterprises and in a digital trade infrastructure context, promote ‘smart customs, smart borders and smart connectivity’ reportedly in service of ‘global trade security and facilitation’ (CIKD 2023).

With links to climate–environmental and technology control risk domains, Table 1 details numerous critical minerals trade agreement initiatives in the early 2020s involving multiple sets of trade partners co-managing shared and emerging economic security risks arising in the sector. While negotiations on many agreements were instigated in response to tax credit provisions in the US Inflation Reduction Act, the underlying imperative is to expand supply capacity of critical minerals required to scale up climate–environmental technologies. The EU, Japan, and US import 98 percent, 90 percent, and 80 percent, respectively, of their critical material needs, China being in many cases the primary source (Pangestu 2023). In a weaponised interdependence context, certain countries are leveraging their dominant trade supply positions. For example, in 2020, Indonesia introduced export controls on nickel ore reserves to incentivise domestic processing and develop a leveraged position with trade partners, subsequently extending the trade policy to bauxite and other metals (Patunru 2023). We later discuss how from 2023, China began applying export controls on targeted critical minerals in retaliation against US restrictions on advanced semiconductor technology transfers.

4. Geopolitical Volatility Risk

This risk domain has somewhat complex and contradictory characteristics. Great power rivalry is a common feature of a neorealist international order, and levels of geopolitical volatility can be generally cyclical in pattern (Dodds 2009). Risk society theory often comments on the co-determinate relationship between geopolitical volatility and global-scale economic and other risks (Beck 2008; Beck and Grande 2010; Denney 2005; Taylor-Gooby and Zinn 2006). For example, an attempt by China to reclaim or blockade the island territory of Taiwan would have profound ramifications for world semiconductor production and consequently up to an estimated 10 percent (USD 10 trillion) loss in global GDP: Taiwanese firms account for around 50 percent of the sector’s manufacturing.12 The skewed or asymmetrical global development of critical trade–industrial systems like semiconductors, where the commercial ecosystem exhibits certain fragilities, makes them highly susceptible to geopolitical volatility risk. This itself has generally escalated due to important structural changes in the global system, primarily China’s ascendance as an economic superpower and its systemic rivalry with the US, the rise in other large developing economy nations, and Russia’s revisionist power aspirations (Mearsheimer 2021).

Trade policymaking in the context of growing geopolitical volatility risk is a balancing act involving multiple and often conflicting objectives. Risk society analysis proposes that this kind of risk is best managed through the ‘cosmopolitanism’ of multilateral or global society-based collaboration (Beck 1996; Beck and Grande 2010). Strengthening trade multilateralism and advancing trade-based international cooperation in new areas are instances of geopolitical volatility risk mitigation, aligned with neoliberal institutionalist thought. However, governments may alternatively prioritise reducing the risk of exposure to coercive trade or other commercial policy measures from geopolitical rivals, including attempted exercises of weaponised interdependence. In this scenario, national security becomes increasingly core to trade policymaking. At the extreme, these countermeasure policies have trade decoupling objectives but can also comprise trade derisking measures. With links to economic security risk, the major powers introduced trade–industrial policies in the early 2020s designed to reduce economic ties with ‘untrusted’ countries and conversely augment friendshoring links with ‘trusted’ or ally countries, thus balancing neorealist and neoliberal motives.

Domestic politics is also vital to understanding why the major powers have adopted derisking trade policies when confronted with escalating geopolitical volatility risk. The worldwide rise in populist nationalism in the 2010s, epitomised by the first Trump presidency, is associated with a corresponding rise in trade protectionism, economic nationalism, and push-back against globalisation (Dent 2020; Evenett 2019). Subsequently, strong domestic political support existed in many countries for the more ambitious trade–industrial policies that later followed in the 2020s aimed at strengthening economic security and competitiveness to counter threats from geopolitical rivals. These policies are based on the neomercantilist principles of protecting domestic industries whilst simultaneously promoting export production and competitiveness. President Biden generally maintained most elements of Trump 1.0 trade protectionism but introduced new trade–industrial policies such as the later examined CHIPS Act and IRA, promoting domestic production in frontier technology industries to gain competitive advantage over other states (Hufbauer 2023), thus with links to technology control risk.

Launched in 2022, the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) was conceived as a multi-sector transregional agreement based on four ‘pillars’, mostly trade-focused (Table 1). Although negotiations on IPEF were terminated early in Trump’s second term, it was ultimately devised to further derisk the US’ trading relationship from China mainly through encircling its systemic rival through friendshoring initiatives (Reeves 2024). While also being understood as a response to geopolitical volatility risk, IPEF also risked compelling China to push ahead with its own counterpart transregional trade diplomacy initiatives—the aforementioned GDI, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and BRICS group—thus only escalating risk conditions (Zhang 2024).

US trade policy under Trump 2.0 appeared to embrace geopolitical volatility and moreover create a disruptive trade relations environment through adopting high tariff protectionism aimed at rivals and friends alike. While ultimately counterproductive by inducing aforementioned retaliatory responses from major trade partners in particular and almost universally raising the transaction costs of trade, it provided an opportunity for the US to create new trade policymaking narratives on tariffs it planned to define and shape.13 Moreover, Trump has long been ideologically wedded to the idea that aggressive use of tariffs affords the US coercive bargaining power in trade negotiations14, and that uncertainty regarding their deployment can too be weaponised for economic and geopolitical ends. It nevertheless simultaneously injected more risk into the global trading system through stoking adversarial trade relations and further eschewing multilateralism, with feedback effects on geopolitical volatility that negatively impacts on all countries (WEF 2025). While at the time of writing, the US’ trade policy remained somewhat in a state of flux, it can be expected to maintain an aggressive tariff policy due to Trump’s aforementioned ideological position. Consequently, we may anticipate a dynamic reflexive modernity pattern of response and counter-response in the new geopolitical volatility risk environment created by the Trump 2.0 presidency during the late 2020s.

The EU meanwhile has been caught in the middle of US–China geopolitical rivalry. In the late 2010s, Trump’s ‘America First’ trade diplomacy and the Chinese government’s own trade–industrial strategies initiated in response set in motion a new EU trade policymaking process to more strongly defend its own economic interests (ECIPE 2022). The underlying principle of the EU’s 2021 New Trade Strategy (European Commission 2021) was ‘open strategic autonomy’ that would establish an open, sustainable but more assertive EU trade policy (Table 1). This marked a departure from its predecessors, the 2006 Global Europe strategy, and its overt emphasis on trade liberalisation and market access, and the 2015 ‘Trade for All’ strategy where trade-capacity building in developing countries was a priority (Bilal 2021). Lavery (2023) furthermore argued that the new strategic autonomy principle of EU trade policymaking had geopolitical echoes of ‘Fortress Europe’ from the late Cold War period. In a neorealist context, the EU Anti-Coercion Instrument came into force in October 2023 as an extension of the Strategy, comprising various offensive trade policy instruments potentially applied when defending European trade interests against aggressor nations (Table 1).

China’s trade policymaking in response to perceived geopolitical volatility risk in the 2020s has taken certain forms. The earlier discussed Dual Circulation Strategy can be understood in terms of limiting the country’s exposure to geopolitical uncertainties though more in a trade autarkic context. China has also afforded greater priority to strengthening trade and wider economic security links with its BRICS group allies (Cao et al. 2023). Brazil, India, Russia, and South Africa all provide China with vital energy fuels, metals, and minerals. Although intra-BRICS trade remains relatively small, China as de facto group leader has recently looked to realise BRICS’ potential as a geopolitical significant trade bloc, mainly through group expansion with developing countries (Papa and Chaturvedi 2023). In January 2024, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates became new full members. While outcomes here are yet to be determined, BRICS diplomacy could become an increasingly important front for China’s trade policymaking responses to geopolitical volatility risk as the decade unfolds. The aforementioned GDI launched in 2021 is another example of China’s trade-based friendshoring strategy, and as Zhou et al. (2023) observed, was integral to the country’s broader shift from a defensive trade strategy to an increasingly offensive one with respect to exporting China’s values, norms, standards, institutions, and model of trade diplomacy. This also includes China geopolitically positioning itself as a champion of developing country causes in the global economy and trade system.

5. Climate–Environmental Risk

In risk society theory, climate–environmental risks are not just accidental byproducts or externalities of modernisation and industrialisation but inevitable functional outcomes of the technologies, systems, and structures they have created (Beck 1995, 2008, 2015; Marshall 1999; Sovacool 2025). Connections here exist with the notion of the Anthropocene, our current epoch where today’s global human activity is radically transforming the planet’s surface and biosphere at a super-accelerated pace (Chernilo 2021; Kesselring 2024). Climate–environmental risks are proliferating in form, and reflexive modernity responses to them are typically set in interlinked policy contexts where trade has become a more salient feature. Furthermore, international trade is simultaneously viewed as generating certain resource efficiencies in the global economy through comparative advantage specialisation but also a growth-oriented engine of unsustainable production, consumption, and distribution. Trade is now linked to around 60 percent of global economic activity—double its share in the 1970s—and directly responsible for up to 30 percent of all carbon emissions, making it critical to climate action efforts (WTO 2021a, 2022). Equally, climate change can significantly disrupt and pose various risks to trade itself, due, for example, from increasingly regular extreme meteorological events (WEF 2024). Consequently, both climate change mitigation and adaptation are being increasingly factored into trade policymaking (UNCTAD 2021; Villars Institute 2024; WTO 2021b).

Various trade policy measures are being devised to manage climate–environment risk, including carbon pricing mechanisms, liberalising trade in environmental goods and services, eco-labelling of imports and exports, eco-fair trading, and decarbonising trade transportation. While environmental-related provisions have long been incorporated into free trade agreements, their legalised commitments to introduce new rules and regulations in this area have hitherto been generally weak (Dent 2021, 2022). However, the growing acknowledged risks associated with climate change have created greater impetus on trade–climate policymaking specifically. Four important new developments here started to emerge in the 2020s. First, the negotiation of new hybrid agreements combining trade and climate–environment themes. Second, the launch of the world’s most ambitious carbon border adjustment trade policy. Third, various different sector-specific policies where trade policy measures are co-opted to realise wide-ranging environmental and climate action objectives, involving IPE constructivist perspectives on the evolving social construction of trade-related risks. By extension, this includes policies of special relevance to critical IPE theories in addressing trade in goods at risk of modern slavery, forced and child labour, and other Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) challenges that adds a socio-environmental risk element to this risk domain. Fourth, the WTO and other relevant global economic organisations have made a step change in tackling trade–climate issues.15 In the climate–environmental risk domain, some of the most novel and innovative trade policymaking of the 2020s may be found.

Taking first new hybrid trade–environment agreements, arguably the highest profile is the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS) involving New Zealand, Costa Rica, Fiji, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. According to its member countries, the agreement ‘has the potential to help bring together some of the inter-related elements of the climate change, trade and sustainable development agendas and demonstrate how they can be mutually reinforcing’.16 Table 1 details the five areas where ACCTS seeks to establish new trade rule precedents, these closely corresponding with the later noted WTO dialogues addressing climate–environmental risk. When enacted, ACCTS could establish new trade norms on derisking climate and environment issues at the multilateral level, and through its intent to expand the agreement’s membership pioneer a new kind of trade–climate club. Meanwhile, the Singapore-Australia Green Economy Agreement (GEA) was signed in October 2022 with multiple climate–environmental goals related to trade policymaking measures across two-thirds of its action themes. This was soon followed by the UK-Singapore Green Economy Framework agreement signed in March 2023 and billed as a ‘hybrid trade and climate framework’ based on three pillars (Table 1). Both bilateral agreements are useful examples of trade policymaking on climate–environment risk embedded in interlinked policy contexts, and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD 2023) predicts that we can expect the gradual expansion of hybrid trade–environment agreements this decade.

The EU remains the global leader on carbon trade diplomacy and trade–climate policy (Arroniz and Peters 2022; Bronckers and Gruni 2021). Its most ambitious and controversial such policy is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), initially implemented from October 2023 and due to become fully operational in 2026 (Table 1). A growing number of carbon border adjustment schemes are in development, but the EU CBAM is by far the most advanced and prominent (Zhong and Pei 2023) and provides the model for the UK’s own such mechanism introduced in 2024. CBAM incentivises the decarbonisation of goods imported into the EU, thereby influencing policy and regulatory changes on carbon pricing beyond Europe. Under the trade policy, carbon tariffs are applied to products entering the EU not yet subject to an existing EU-equivalent carbon pricing system. It is viewed by some as ‘green protectionism’, especially by developing and carbon-intensive countries. Additionally, significant complications may arise in CBAM’s carbon accounting and certification of supply chain traded goods involved in multiple border crossings (Batra 2023). This reveals the problems that can arise from tackling global climate–environmental risks through unilateral trade policymaking rather than multilateral approaches. History nevertheless suggests that trade policy innovation often relies on first mover initiatives, these frequently being unilateral in nature (Hopkins 2003).

Regarding other key developments also outlined in Table 1, the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles and EU Deforestation Free Commodities directive entered into force in March 2022 and June 2023, respectively, each introducing new trade measures of climate–environment risk relevance. Additionally, negotiations on the EU-US Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminium began in October 2021, aiming to decarbonise production and trade in two of the world’s most carbon-intensive industries. In 2022, both trade partners also initiated trade policies addressing socio-environmental risk, the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence directive and the US Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act. These specifically link trade policy to social SDG issues and like CBAM, is likely to be viewed by developing countries particularly as covert protectionism. Elsewhere, Australia Canada, New Zealand, and Taiwan signed the Indigenous Peoples Economic and Trade Cooperation Arrangement (IPETCA) in December 2021. This hybrid socio-environmental trade agreement is the first of its kind, seeking to strengthen the inclusion of indigenous peoples into international trade activity and conversely address potential risks arising from social exclusion. Table 1 indicates where the climate–environmental risk domain has relevance to a number of other trade policymaking initiatives listed, with a particular strong interconnection with economic security risk given the dependence of emerging green industries on critical mineral supply chains.

With notable relevance also to technology control risk, the 2023 Inflation Reduction Act contained ambitious trade–industrial policy measures backed by USD 500 billion funding support to develop US capabilities in various clean energy technologies (Table 1). Under this Act, foreign firms from countries with an aforementioned critical minerals trade agreement with the United States were eligible for tax credits on EVs they assembled in the US using battery materials that could be sourced from or processed in their home country but with manufactured components mostly from North American-based producers. However, under the Trump 2.0 presidency, the IRA is likely to be phased down or curtailed, depending on how certain Republican lawmakers whose states significantly benefit from the Act vote in Congress.17 More generally though, President Trump’s climate scepticism leads us to expect no further US trade policymaking initiatives in the risk domain during his term of office, with the exception to critical mineral trade agreements—such as the earlier mentioned April 2025 deal with Ukraine—but more for economic security risk reasons.

The 2020s also saw some important new initiatives addressing climate–environmental risk in the multilateral trade regime. In January 2023, the new Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate was formed, bringing together 56 countries to forge closer links between trade and climate policies.18 At the WTO, a number of initiatives have been recently launched, most notably the Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD), Informal Dialogue on Plastics Pollution and Sustainable Plastics Trade, and Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (FFSR) talks, but somewhat uneven progress is being made, thus making it uncertain whether any new multilateral trade rules or agreements on this front will arise (Baršauskaitė 2024).

6. Technology Control Risk

Technological development’s synonymous links with modernisation and industrialisation was earlier discussed in a risk society context. As an important meta-theme, it is viewed as a broad, organic process generating benefits to society but also new forms of manufactured risk (Sundberg 2024). While this development is inherently unpredictable, attempts to control and manage technology generated risks are nevertheless a policy priority for many governments. Beck (1992, 2008) emphasised technology’s capacity for constant disruptive economic, social, and environmental change that create particular dynamic reflexive modernity challenges for policymakers. This can involve measures to develop new technologies to counteract the risks created by incumbent ones, such as renewables and fossil fuel energy (Chernilo 2021; Denney 2005). Potentially high and unpredictable degrees of systemic risk can emerge when introducing new paradigm shift technologies like artificial intelligence (Krummenacher 2023; Pearson and Bardsley 2022), and these may be considered forms of technology control risk.

Technology has shaped both trade and trade diplomacy throughout history, and the control of technology trade is also often inextricably linked to national security (Pigman 2022). Conversely, trade is an important technology transfer mechanism and technology is a common feature of trade policymaking, especially when fused with industrial policy. This typically involves optimising the significant export potential of frontier technology industries and controlling the dispersion of technologies possessing strategic value in co-joined economic security and national security risk contexts (Starrs and Germann 2021). A new wave of trade–industrial policies was initiated in the 2020s based principally on neomercantilist motives of achieving some form of controlling position in frontier technology industries, particularly those associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution: artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, clean energy, quantum computing, synthetic biotechnology, cybernetics, advanced pharmaceuticals, genetic engineering and mobile telegraphy. Again, this marked a normative shift in trade policymaking from neoliberalism to neorealism.

From a trade risk society perspective, efforts to manage technology control risks in the 2020s through trade policymaking can be understood from three different but overlapping perspectives. First, regarding technology production, establishing a commanding position in supply chains of frontier technology industries, especially when trying to counteract any acquired dominance that rival trade nations have hitherto attained in them, e.g., China in electric vehicles and storage batteries. Second, export restrictions in key technical components and critical minerals on which frontier technology industry development depends. Third, more generalised contested control over tradeable advanced technologies that confer strategic advantage and various forms of economic, military, and other forms of power. Controlling the dispersion of national security relevant technologies through trade–industrial policies may be viewed as more imperative in times of escalating geopolitical volatility risk, although the simultaneous intensification of techno-industrial competition arising from these actions can further escalate it. Developments in other risk domains may also amplify technology control risks. For example, managing climate–environmental risk is driving the expansion and export of clean energy technologies, while securing the critical minerals required to achieve the same goals in other frontier technology industries is relevant to economic security risk.

Arguably the most important new trade policymaking initiatives in this risk domain concern the semiconductor industry, involving technologies indispensable to the operation of modern economies and societies. Control over semiconductor technology is furthermore increasingly critical in the dawn of artificial intelligence (AI). American firms (e.g., NVIDIA and Intel) are dominant in the design of advanced semiconductors (i.e., microchips or chips), Taiwanese companies are involved in semiconductor production, while Dutch firm ASML monopolises the construction of photolithography machines needed to manufacture semiconductors. Each machine typically comprises 100,000 parts sourced from a global network of many thousands of firms, indicative of the complex supply chain trade ecosystems that have evolved over many decades (Miller 2022). Establishing positions of control over these ecosystems has proved extremely challenging due to problems arising when attempting to disentangle and reconfigure them. Yet this has not stopped the major trade powers from trying (Kreps and Timmers 2022).

US efforts thus far this decade centre on the bipartisan supported 2022 CHIPS19 Act based on the goals of improving semiconductor supply chain resilience and countering China’s technological development in the sector (Table 1). The USD 52.7 billion funded Act includes production subsidy support and reshoring investment incentive measures aimed at reducing import demand and boosting exports of US-made semiconductors while also exercising export controls on advanced semiconductor technology. These included stronger trade restrictive measures than embodied in the 2018 US Export Control Act and other related policies of the first Trump administration (Glosserman 2023; Sheehan 2022). In November 2022, under the CHIPS Act, the US also banned the imports of five Chinese technology firms, including Huawei and ZTE, citing security concerns.20 Thereafter followed a succession of retaliatory actions where China imposed export restrictions of its critical minerals (e.g., gallium and germanium) essential for semiconductor manufacture followed by further technology export restrictions imposed by the US, continuing into 2025.21 The shock announcement in January that year of Chinese company DeepSeek’s AI model—developed at a fraction of the cost of its Western rivals and exposing inefficacies of US export controls—led to the Trump 2.0 administration retaining the CHIPS Act but managed by the newly created US Investment Accelerator agency.22

The response of business to these policy actions was mixed, with relevance to the prior discussed issues of weaponised interdependence and state–business agency under economic security risk. The US Semiconductor Industry Association criticised the Biden administration’s trade policy actions for the ‘risk harming the US semiconductor ecosystem without advancing national security as they encourage overseas customers to look elsewhere’.23 American firm NVIDIA also complained against the measures that blocked exports of its two AI microchips specifically developed for the Chinese market, representing a quarter of its worldwide sales (Ibid). Meanwhile, in June 2023, ASML announced its compliance with US requests to curb its photolithography machine exports to China.24 With regard to friendshoring, in February 2022, the US proposed a CHIP-4 Alliance with Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea in a further move to counteract China’s influence in the sector. This followed on from the Biden administration’s subsidy incentives to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC)—the world’s largest microchip producer that makes over 90 percent of the most advanced (3-nanometre) chips—to establish a large factory in the US.25 Due to delays, the firm’s new USD 40 billion chipmaking plant located in Arizona is expected to start production in 2028. The Japanese government also created a similar deal with TSMC, with its new plant opening at Kumamoto in 2024, as had the EU with the Taiwanese manufacturer, a EUR 38 billion factory project in Dresden, Germany scheduled for full operation in 2027.26

The 2023 EU European Chips Act was developed largely in response to the US CHIPS Act. Europe’s semiconductor industry has relatively languished and seriously suffered from supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Timmers 2022). The EU Act is a EUR 43 billion funded multi-pillar strategy to improve Europe’s trade competitiveness and export capacity in the sector (Table 1), extending the aforementioned ‘open strategic autonomy’ principles of the EU 2021 New Trade Strategy to mitigate technology control risks affecting European semiconductor producers. By this time, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan had too introduced similar subsidy measures to support their own semiconductor industries27, and in 2022, the Chinese government announced a new USD 143 billion state support programme for its own sector.28

Over recent years, China’s own trade–industrial policies in the semiconductor and other frontier technology sectors have particularly aimed at addressing what Murphy (2022) terms ‘technology chokepoints’, most importantly supply chain dependencies on foreign companies, as well as gaps in domestic industry capacity and R&D activities—hence with economic security risk relevance also. The ‘Made in China 2025’ master industrial plan was devised in the mid-2010s to avert the country falling into the middle-income trap facing newly industrialising economies of remaining an export platform for foreign enterprises. The plan was essentially an indigenous innovation strategy for developing China’s own frontier technology industries based also on export-driven growth (Starrs and Germann 2021). Launched in 2020, the ‘China Standards 2035’ programme follows on from the Made in China 2025 plan as a technology control strategy to strengthen the country’s influence in determining international technology standards that in turn will shape future patterns of technology trade across multiple sectors.29 Partly as a result of this new programme, Chinese enterprises’ global share of all 5G-related ‘standard essential’ mobile telegraphy patents had risen to a third by 2022, with implications for many advanced technology sectors dependent on remote connectivity such as autonomous vehicles (Lee 2022).

From a more ‘cosmopolitan’ risk society perspective, Table 1 details the new trend of digital trade agreements emerging in the 2020s motivated by filling trade rule-making gaps on digital technology not being plugged by FTAs or the WTO. Chile, New Zealand, Singapore, Ukraine, UK, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) group represent the pioneers on this front that includes addressing the still largely unknown technology control risks posed by artificial intelligence and its potentially significant disruptive impacts on trade (Krummenacher 2023).

7. Conclusions

Profound changes in trade policymaking are taking place in the 2020s in response to a complex set of increasingly salient risks shaping the international trade system. Drawing upon the influential theory of risk society, this study develops a new trade risk society (TRS) framework providing original insights and new conceptual thinking on the subject, as summarised in Figure 1. This analytical approach extends beyond merely a topical evaluation of current risks in the international trade system to one that embeds trade in deeper underlying developments in our contemporary world and challenges facing it. Concepts underpinning risk society theory, such as reflexive modernity, provide adapted core elements of the framework while its more empirically specific analytical functions centre on the following four risk domains: 1. Economic security. 2. Geopolitical volatility. 3. Climate–environmental. 4. Technology control. Interconnections between these domains were made throughout the framework’s application in analysing the 30 or so most significant trade policymaking initiatives introduced thus far this decade by the world’s major trade powers and middle-ranking trade nations (Table 1). This pattern of initiatives is indicative of a paradigm shift in trade policy norms emerging in an increasingly volatile and contested world that can be best understood in a trade risk society context.

In drawing final conclusions, the TRS framework provides valuable explanations for the recent advent of more defensive unilateralist policies, often based on the twin goals of protecting domestic industries and promoting export production and competitiveness. This turn to neomercantilism fuels contestability in international trade relations that could significantly fragment and splinter the global trade system, including by further undermining the already ‘at risk’ multilateral trade regime. Normatively and ideologically speaking, a corresponding shift from neoliberalism to neorealism trade policymaking in the 2020s is evident, where various forms of state intervention (e.g., trade–industrial policies and tariffs) are being deployed as derisking responses to perceived free market failures and other economic predicaments. We have also seen the evolving social construction of trade-related risks where critical IPE perspectives help explain the development of trade policymaking innovations centred on hybridised trade, environment, and social agreements among trade partners. These are key norms and normative implications stemming from a TRS analysis of trade policymaking in the 2020s.

There are some important policy recommendations arising from this study. For example, trade policymakers’ attempts at complete risk avoidance can both reduce the scope for reward and over time lead to new vulnerabilities to longer-term threats as a consequence of over-insulation (Roberts 2023). Managed exposure to risks tends to gradually condition economies to become more resilient, where controlled risk ‘stress-tests’ can identify systemic weaknesses as well as strengthen preparedness for managing future risks (Taleb 2012). Effective derisking approaches to trade policymaking in the 2020s thus involves striking the right balance regarding managed risk exposure. Thus, countries striving to completely decouple their trade with China is likely to prove the riskiest overall pathway. Similarly, endeavours to re-engineer complex supply chain trade ecosystems through homeshoring and other trade policy measures may simply raise domestic market costs and prices, and lower national efficiency and productivity, eventually creating more substantive longer-term risks to the national economy. This similarly applies to Trump 2.0 tariff protectionism and consequent insulation of domestic firms from the disciplines of foreign competition.

We have seen that while derisking trade policymaking initiatives this decades have seen a rise in more defensive unilateral measures, there too have been notable collective actions such as bilateral, regional, and plurilateral pacts among trade partners. This study contends that trade-related risks examined under the TRS framework are invariably better managed and addressed by multilateral collective action (i.e., relating to Beck’s ‘cosmopolitanism’) that provides the basis for broad, constructive cooperation, thus helping avoid inter-state conflict and rivalry, establish more a stable international trade order, and more effectively deal with spillover effects on third parties. Support for stronger trade governance and reform at the WTO working in tandem with other relevant global multilateral institutions to more collectively address these risks is another important policy recommendation. We saw how recently the WTO has gained some traction on tackling climate–environmental trade risks but this could be extended to issues such as critical minerals trade. Future TRS research on how to develop a stronger multilateral and inclusive trade risk society is being argued here.

Yet the prospects for stronger trade multilateral governance look slim, especially due to the international trade disorder caused by US President Trump’s aggressive tariff protectionism initiated in early 2025. The Trump 2.0 presidency’s impact on trade policymaking in the second half of the decade will broadly depend on the conversion of stated intent on high tariff protectionism into actual practice, and consequently how targeted trade partners respond to this with combinations of retaliatory tariffs or other countermeasures. Whatever transpires, Trump’s ‘America first’ ideology is inherently anti-multilateral and averse to international collective action. While this has significant general implications for trade policymaking over forthcoming years, this study points to other profound new trends in trade policymaking during the 2020s that look to continue unabated. For example, trade risk society explains the emergence of new hybrid and other types of trade agreements that may increasingly displace or supersede free trade agreements. FTAs have been the dominant trade diplomacy norm since the 1990s but new signed agreements have markedly declined in annual number since the mid-2010s.30 Most recently, they have been exposed as generally under-equipped in dealing with new disruptive developments in trade policymaking. The new types of bilateral and multi-party trade agreements examined in this study represent more benign forms of trade policy innovation.

This study also recognises that developing countries often lack various forms of capacity to manage or navigate a path through the trade risk domains and may depend on the collective actions of more powerful countries and international institutions to mitigate common risks and trade security public goods. This includes certain regional and new forms of trade agreements, most of which has gained some traction, and has been important at a time when the WTO is essentially inert. However, in the disruption caused by Trump 2.0 tariff protectionism to the international trade system, many developing countries have been proportionately hit the hardest from the economic security risks arising. For example, in order to compensate to some degree from a new 50% tariff on Lesotho’s textile exports to the US, the government considered lowering its labour standards and adopting other compromising measures to avoid the possible collapse of this sector in the small southern African nation.31 Developing countries also frequently suffer disproportionately from the impacts of many climate–environment risks (e.g., flooding, rising sea-levels, drought) but lack the trade policy tools to address them, again depending on others with stronger technocratic capacity to provide them but that does not place them at a disadvantage. As was discussed, accusations of ‘green protectionism’ from lower-income economies regarding the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has relevance here. The application of the TRS framework to developing countries more specifically is a promising avenue for future research, with this linked to another policy recommendation for developed economies to take into account how their derisking trade policies impact on developing nations.

Looking further ahead, the TRS framework’s relevance beyond the 2020s ultimately depends on future developments across its four risk domains, these being closely interlinked. The long crisis of climate change looks set to worsen as high global carbon emission levels are anticipated to persist, making the clean energy transition increasingly urgent. This will consequently further accelerate the demand for critical minerals on which this transition depends, applying growing pressure to expand the production and trade of these resources that in doing so creates additional economic security risks in an increasingly resource scarce world. Relatedly, more advanced countries will continue to seek control over strategically important and disruptive technologies pivotal to future global economic development. Competition for technology control will only intensify as systemic rivalry between the major and middle-ranking trade powers deepens, where we can expect the geopolitical environment to remain highly volatile. In sum, we continue to live in a risk society and need to comprehend trade’s increasingly pivotal position in it. This study has developed the TRS framework for this purpose, and for better understanding profoundly important developments in trade policymaking taking place this decade and most likely into the next.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In the 15-page official Strategy document, the word ‘risk’ is mentioned 77 times, mostly in connection with trade-related issues. |

| 2 | CSIS News, 20 December 2024, ‘Trump Trade 2.0’, www.csis.org/analysis/trump-trade-20 (accessed on 12 February 2025). |

| 3 | BBC News, 6 February 2025, ‘The tariff wars have begun: buckle up’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c8975dx1pe3o. Accessed on 12 February 2025. |

| 4 | BBC News, 1 February 2025, ‘China, Canada and Mexico vow swift response to Trump tariffs’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c627nx42xelo. Accessed on 12 February 2025. |

| 5 | Reuters, 12 March, ‘Canada announces C$29.8 billion in retaliatory tariffs on US’, www.reuters.com/world/americas/canada-announce-c298-bln-retaliatory-tariffs-us-2025-03-12. Accessed on 19 March 2025. |

| 6 | NPR News, 12 March 2025, ‘Automakers brace for higher costs as steel and aluminium tariffs kick in’, www.npr.org/2025/03/12/nx-s1-5325933/steel-aluminum-tariffs-autos. Accessed on 19 March 2025. |

| 7 | These new ‘reciprocal’ tariffs were presented by Trump as being half the import tariffs allegedly applied by trade partners on their own imports from the US but this transpired to be a misnomer. Instead, these announced new tariffs were calculated by taking the goods trade deficit (ignoring services trade) the US had with the partner country then dividing this by the US’ imported goods value total from that trade partner. Many countries targeted for higher-level tariffs did not apply any restrictions, tariffs or otherwise, on the US. BBC News, 3 April 2025, ‘Why Trump’s tariffs aren’t really reciprocal’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/videos/c14xldg3mjvo. Accessed on 5 April 2025; CSIS News, 3 April 2025, ‘Liberation Day Tariffs Explained’, www.csis.org/analysis/liberation-day-tariffs-explained. Accessed on 5 April 2025. |

| 8 | Where later in April 2025, the US applied a 145% tariff on most goods from China, who in turn applied a 125% tariff and other trade restrictions on targeted imports from the US. A partial de-escalation of tariff rates was later brokered between both sides the following month. |

| 9 | Guardian, 7 Jan 2025, ‘Trump refuses to rule out using military to take Panama Canal and Greenland’, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jan/07/trump-panama-canal-greenland. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 10 | Guardian, 17 Feb 2025, ‘What are Ukraine’s critical minerals—and why does Trump want them?’ www.theguardian.com/world/2025/feb/17/what-are-ukraines-critical-minerals-and-why-does-trump-want-them. Accessed on 19 March 2025; BBC News, 30 April 2025, ‘US and Ukraine sign long-awaited natural resources deal’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c5ypw7pn9q3o. Accessed on 5 May 2025. |

| 11 | The Diplomat, 11 July 2023, ‘China’s Transition from the Belt and Road to the Global Development Initiative’, https://thediplomat.com/2023/07/chinas-switch-from-the-belt-and-road-to-the-global-development-initiative. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 12 | Bloomberg News, 9 January 2024, ‘Xi, Biden and the $10 Trillion Cost of War Over Taiwan’. www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-01-09/if-china-invades-taiwan-it-would-cost-world-economy-10-trillion?embedded-checkout=true. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 13 | CSIS News, 30 April 2025, ‘Can Trump’s Reciprocal Trade Negotiations Make America Great Again?’, www.csis.org/analysis/can-trumps-reciprocal-trade-negotiations-make-america-great-again. Accessed on 5 May 2025. |

| 14 | East Asia Forum, 30 April 2025, ‘Making sense of Trump’s tariffs’, https://eastasiaforum.org/2025/04/30/making-sense-of-trumps-tariffs. Accessed on 5 May 2025. |

| 15 | For example, the annual WTO Public Forum events focused on these issues, www.wto.org/english/forums_e/public_forum23_e/public_forum23_e.htm. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 16 | Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (New Zealand): https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/trade-and-climate/agreement-on-climate-change-trade-and-sustainability-accts-negotiations. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 17 | The power to repeal the IRA lies with US Congress, not President Trump. Columbia Climate Law, 29 April 2025, ‘100 Days of Trump 2.0: The Inflation Reduction Act’, https://blogs.law.columbia.edu/climatechange/2025/04/29/100-days-of-trump-2-0-the-inflation-reduction-act. Accessed on 5 May 2025. |

| 18 | See www.tradeministersonclimate.org. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 19 | ‘Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors’. |

| 20 | BBC News, 26 November 2023, ‘US bans sale of Huawei, ZTE tech amid security fears’. Available at: www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-63764450. Accessed on 9 January 2025. |

| 21 | EAF, 19 February 2025, ‘How China is weaponising its dominance in critical minerals trade’, https://eastasiaforum.org/2025/02/19/how-china-is-weaponising-its-dominance-in-critical-minerals-trade. Accessed on 9 March 2025. |

| 22 | Tech Target News, 9 April 2025, ‘Trump puts stamp on CHIPS Act deals with new office’, www.techtarget.com/searchcio/news/366622293/Trump-puts-stamp-on-CHIPS-Act-deals-with-new-office. Accessed on 5 May 2025. |

| 23 | BBC News, 18 October 2023, ‘US-China chip war: Beijing unhappy at latest wave of US restrictions’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-67141987. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 24 | BBC News, 30 June 2023, ‘Dutch to restrict chip equipment exports amid US pressure’, www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-66063594. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 25 | Samsung was also approached around this time to establish a new semiconductor plant in the US. |

| 26 | Reuters, 8 August 2023, ‘Germany spends big to win $11 billion TSMC chip plant’, www.reuters.com/technology/taiwan-chipmaker-tsmc-approves-38-bln-germany-factory-plan-2023-08-08. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 27 | Korea Herald, 24 January 2022, ‘Korea sets out own Chips Act, in less ambitious fashion’, www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220124000671. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 28 | Reuters, 13 December 2022, ‘China readying $143 billion package for its chip firms in face of US curbs’, www.reuters.com/technology/china-plans-over-143-bln-push-boost-domestic-chips-compete-with-us-sources-2022-12-13. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 29 | China Briefing, 20 July 2020, ‘What is the China Standards 2035 Plan and How Will it Impact Emerging Industries?’, www.china-briefing.com/news/what-is-china-standards-2035-plan-how-will-it-impact-emerging-technologies-what-is-link-made-in-china-2025-goals. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 30 | See WTO Regional Trade Agreement Database at: https://rtais.wto.org. Accessed on 14 October 2024. |

| 31 | News Central Africa, 6 May 2025, ‘Lesotho’s Textile Sector Braces Up as Trump-Era Deadline Nears’, https://newscentral.africa/lesothos-textile-sector-braces-up-as-trump-era-deadline-nears. Accessed on 14 May 2025. |

References

- Adamchick, Julie, and Andres M. Perez. 2020. Choosing awareness over fear: Risk analysis and free trade support global food security. Global Food Security 26: 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]