Abstract

Limited access to education in rural areas of Senegal is a structural barrier to human development and equal opportunities. The Bicycles for Education project, promoted by the Utopia Foundation—Bicycles Without Borders (BSF), aims to improve the educational participation of young people aged 12 to 21 by providing bicycles to facilitate their travel to school. In this study, the GRITS research group from the University of Barcelona externally evaluates the impact of the project on improving access to education, reducing gender inequalities, and the associated socioeconomic as well as community benefits. A qualitative approach based on individual interviews (n = 23), focus groups (n = 6) and group interviews (n = 8) was used, with a total of 80 participants, including students, families, teachers, project coordinators, and institutional managers. The analysis was carried out through thematic coding and content analysis, identifying four main axes: educational impact, gender equity, economic effects, and community transformation. The results show that the provision of bicycles throughout the school year led to increased school attendance and punctuality, improvements in academic performance, a reduction in social inequalities, gender inequalities in access to education, and a decrease in household costs associated with transport and food. In addition, there has been a cultural transformation in the perception of cycling as a viable means of mobility and a change in those communities where the project has been running for more than a decade.

1. Introduction

Inequality in access to education represents a structural barrier that limits socioeconomic development and equal opportunities in various regions of the world. In this context, innovation and international cooperation are positioned as key strategies with which to mitigate these inequalities, particularly in rural areas where the distance between homes and educational institutions is a significant barrier to schooling. This highlights the importance of strategic planning that considers both theory and practice in addressing local development, which is relevant to understanding how projects such as ‘Bikes for Education’ fit into a broader community development framework (Blakely and Leigh 2013).

In the field of Social Work, there is a growing interest in exploring innovative tools that transcend traditional approaches, both in local contexts and in experiences of international cooperation. These tools serve a dual purpose: firstly, to deepen the analysis of social transformation processes (Strasser and de Kraker 2023), and secondly, to evaluate interventions that face specific complexities in diverse settings (Lenz and Shier 2021). The ‘Bikes for Education’ project, initiated in 2015 by the Utopia Foundation—Bikes Without Borders (BSF) in Girona (Spain), emerges as an innovative intervention with which to improve accessibility to secondary education in Senegal. Based on models previously implemented in India and underpinned by principles of international cooperation, the project aims to facilitate access to education for young people aged between 12 and 21 by providing them with bicycles, called Baobikes, for their daily commute to school. Accordingly, it highlights the need to promote inclusion and participation through strategies to improve access to education in rural communities (Mitlin and Satterthwaite 2013).

In this context, the present study arises from the collaboration between a foundation dedicated to sustainable mobility and a research group in Social Work at a Southern European university with the aim of evaluating the impact and effectiveness of the project from its conception to the present day. The analysis and assessment of initiatives, be they projects, programmes, or policies, are aimed at formulating and answering questions that allow their effectiveness to be measured and improvements to be identified. This evaluation process seeks to ensure the efficiency of an intervention through a methodical and comprehensive approach (Ham et al. 2016). From this perspective, evaluation is conceived as a continuous learning process that allows for deciphering the impacts and understanding the causes of project development. It emphasises the importance of the accumulation of knowledge and the subjective perceptions of the actors involved, as well as the individual interpretations they give to the evaluative elements of the intervention. This approach seeks to identify explicit changes in beneficiaries and communities, and also to examine the underlying transformations that influence project continuity and sustainability (Rice and Girvin 2021).

The interaction between evaluative research and intervention in Social Work constitutes a dynamic and continuous process of communication, analysis, and optimisation. Evaluation, far from being limited to a simple measurement of results, is conceived as a reflexive process that allows for understanding the impact of practices and promoting improvements in intervention strategies (Sundell et al. 2023). This critical approach is embedded in all dimensions of the evaluation process, fostering continuous enquiry that drives learning within evaluation teams and strengthens the effectiveness of interventions (Gadaire and Kilmer 2020).

1.1. The Education System in Senegal: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities

According to a report by Paz y Desarrollo (2020), Senegal’s socioeconomic context is characterised by sustained economic growth in recent years, but also by persistent structural inequalities that constrain human development. Despite the expansion of key sectors such as services and industry, a large part of the population still relies on the informal sector, which implies labour vulnerability and low social protection. While macroeconomic indicators have shown improvements, access to basic services such as education and health remains limited, which is evidence of a significant gap between economic growth and well-being.

Rural communities in Senegal have several characteristics that differentiate them from the urban context. These areas are located in geographically isolated regions, with low population density and a strong dependence on subsistence agriculture. Infrastructure is limited and access to basic services, such as health and education, is restricted. Life in these communities is closely linked to natural resources and local social organisation, which conditions the economic and social dynamics of the environment. Although each community has its own particularities, these general characteristics largely define their reality and the challenges they face in terms of development and sustainability (Rice and Girvin 2021; Paz y Desarrollo 2020).

The education system in Senegal follows the French model and is characterised by mixed schooling. The Senegalese government allocates approximately 35% of its national budget to education, reflecting its commitment to the development of the education sector (Carneiro et al. 2019). This funding is used to, among other things, build new school infrastructure and improve the quality of education. French is the language of instruction, although Arabic and national languages such as Wolof and Serere are also used (Benson 2020). The education system covers various levels, from early childhood education through to technical and vocational training as well as higher education. However, while primary education is free, secondary and university education is expensive, forcing many students to seek employment to finance their studies (Coquéry-Vidrovitch 2021).

Despite the fact that primary education is free, families have to bear indirect costs such as transport, food, and school materials, which is a barrier to access to education (Crespin-Boucaud and Hotte 2021). In addition, there are opportunity costs linked to household chores, as children and adolescents who attend school have less time to devote to these tasks. Sending their children to school is therefore a double effort for families, especially for girls, who generally have more obligations in terms of household chores (Xaley 2018). The distance between homes and schools is another major obstacle, as many students must travel long distances on foot, exposing them to risks on main roads or roads without adequate infrastructure (Newman 2019).

The rural education system in Senegal faces multiple challenges that affect its effectiveness and accessibility. One of the main problems is the insufficient number of school places, which leads to overcrowded classrooms and limits participation in education (Dieng Diasse and Kawai 2024). Demand for education far outstrips supply, leaving many children unable to secure a place in school (Seye Djité and Diakhate 2019). This overcrowding has led, on numerous occasions, to teacher strikes that disrupt the normal course of the school year, negatively affecting the quality of education (Kane and Martin 2023; Le Quotidien 2022). This scenario not only affects the quality of education but also reflects the urgent need to expand and improve educational infrastructure in the country.

The scarcity of financial resources represents one of the main challenges in Senegal’s education system. Educational institutions and families face significant economic constraints that hinder the development of educational projects and restrict student participation. The lack of electricity and other essential supplies directly affects school activities, limiting the printing and distribution of teaching materials (Seye Djité and Diakhate 2019), as well as restricting the use of technologies in the classroom (Daff et al. 2019). This situation reflects the economic precariousness of many families, which constitutes an additional barrier to equitable access to quality education (Oyekale 2023).

Structural and cultural difficulties within the Senegalese education system also impact its efficiency. These barriers are deeply rooted in the organisation and management of schools, as well as in cultural practices that affect the implementation of pedagogical reforms and innovations (Aguiton 2020). The lack of adequate infrastructure and the deficit of qualified teachers aggravate the situation, creating sub-optimal learning conditions for students (Leone et al. 2022).

Another significant challenge is accessibility to schools. In many rural regions, distances between homes and schools are considerable, making it difficult for students to attend regularly. The lack of an efficient transport system contributes to school dropout, especially among children from low-income families (Dieng Diasse and Kawai 2024). This problem limits the expansion of education in remote areas and perpetuates inequality in access to educational opportunities (Newman 2019).

Despite these challenges, Senegal has been a key player in regional initiatives to strengthen education in Africa. In 2001, the country became one of the driving forces behind the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), a plan conceived by African leaders with the aim of reducing the continent’s marginalisation and fostering its development through domestic efforts and international cooperation (Brossier 2024). More than two decades later, this initiative is still in place and has been reaffirmed in forums organised by the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), consolidating education as a strategic priority for the continent’s future (Koddenbrock et al. 2022).

At the national level, the Senegalese education system reflects both the challenges and opportunities of this regional commitment. Formal education, especially in rural areas, faces multiple challenges, but also presents opportunities, particularly in terms of the active participation of students and families in the educational process (Diallo et al. 2023). In this context, secondary education requires the implementation of innovative strategies that reduce access barriers and promote greater student retention, thus ensuring equitable opportunities for the academic and social development of young people.

1.2. Education on Wheels: Bicycles as a Development Tool in Senegal

Within this framework, the cooperation project ‘Bicycles for Education’ is implemented in Senegal. Its objective is to provide bicycles to secondary school students (young people from 12 to 21 years old) in this country, in order to facilitate their access and daily commute to their educational centres. This programme is inspired by similar initiatives carried out in India and other regions where mobility is a determining factor in access to education (Dieng Diasse and Kawai 2024; Fundación Vicente Ferrer 2020). This initiative is complemented by the ‘Bicycles for Development’ project, which seeks to support rural communities through sustainable mobility strategies. The criteria for inclusion in the programme require beneficiaries to reside at least two kilometres from their respective educational centres, although in many cases the distance is considerably greater.

Since its inception, BSF has grown significantly and expanded its coverage in rural areas of Senegal. In 2025, the programme benefited eleven educational centres and one student residence located in rural communities such as Palmarin, Fimela, Sandiara, Boyard, Loul Sessène, Samba Dia, Nguéniéne, Warang, Kelle, and Mbour. The beneficiaries include both the students, whose ages range from 12 to 21, and their families and communities. Families contribute a symbolic annual fee of CFA 6000 (approximately EUR 9.2 or USD 9.9) to finance the salary of the mechanic responsible for the maintenance of the bicycles and the purchase of essential spare parts (Salat et al. 2021).

BSF delivers the bicycles, called Baobikes, directly to the schools, who take responsibility for their proper management. As far as the management of the bicycles is concerned, the schools are given autonomy. The schools are in charge of disseminating the project among students and their families who might benefit from it because they live far from the school. However, the demand for bicycles often exceeds the available supply, which has led some schools to establish additional allocation criteria, such as students’ academic performance or socioeconomic status (Sy et al. 2021). The centres also have mechanical workshops where a trained professional takes care of the daily maintenance of the bicycles, as well as adequate parking facilities for their safekeeping.

The use of bicycles is strictly regulated and limited to school transport only. This regulation is intended to extend the useful life of the vehicles in an environment characterised by unpaved roads and adverse conditions. The commitment to respect this regulation is formalised in a contract signed by the parties involved: the student, the family, and the school management team. In the event of failure to comply with the regulations on three or more occasions, the bicycle will be withdrawn from the programme. At the end of the school year, the bicycles must be returned to the project for redistribution to new beneficiaries (Diouf and Miezan 2021).

After more than seven years of project implementation, Bicicletas Sin Fronteras (BSF) identified the need to carry out a rigorous evaluation of the impact of its initiative in the beneficiary communities. In order to systematically analyse the effects of the programme on access to education, equity of opportunities, and improvement in the quality of life of students, the foundation commissioned the GRITS research group (Research and Innovation Group in Social Work) from the University of Barcelona to carry out this evaluation. This study is based on a qualitative methodology to provide a comprehensive analysis of the achievements, challenges, and future perspectives of the project. In this context, this article is the result of this research process, offering a comprehensive view of the impact of the initiative and providing empirical evidence that contributes to the optimisation and sustainability of the programme.

2. Methodology

Evaluation in the field of international cooperation has been consolidated as an essential practice for the continuous improvement of the quality and effectiveness of interventions developed in different contexts (Fernández-Baldor and Boni 2011). In line with this, evaluation makes it possible to assess the results obtained and the impact generated in projects, ensuring more effective evidence-based management (Amin et al. 2022). In this study, the impact of the ‘Bikes for Education’ project was analysed in order to draw conclusions that would contribute to the design of more efficient and sustainable interventions over time.

The methodology used in this evaluation was based on a participatory approach involving various key stakeholders: students, families, school management, teachers, mechanics, and political as well as educational management representatives, in addition to the project management and coordinators in Catalonia and Senegal. This approach sought to value the experiences and perceptions of the participants themselves (Chambers 1997), ensuring that the evaluation not only measured quantifiable results but also the social and community impact of the project (Henderson 2021). The inclusion of these perspectives facilitated a process of empowerment, encouraging decision making based on participatory and equitable analysis, which strengthened ownership of the project by the beneficiary community (Oliveros-Romero and Aibinu 2023).

In order to carry out this evaluation, the following general objective was defined: to analyse the benefits and impact of the ‘Bikes for Education’ project in schools in Senegal, from its beginnings to the present day.

The methodology adopted was based on a qualitative approach, characterised by a structural, contextual, and dialectical perspective. The sample was selected in a strategic and purposive manner to ensure equal representation of the diverse perspectives and experiences of the participants. This methodological design allowed for an in-depth and holistic analysis of the project’s impact, ensuring the inclusion of multiple voices within the education community (Walker et al. 2024).

The possibility of collecting quantitative data to complement the analysis was considered, but it was not feasible, as the available information was unsystematic and very incomplete. One of the recommendations arising from the study is precisely the need to systematise these data so that a more rigorous quantitative analysis can also be incorporated into future evaluations.

Given the qualitative nature of the research, a variety of data collection techniques were employed, including individual interviews, group interviews, and focus groups. These techniques were strategically selected to capture a diversity of perspectives and provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the project on schools and their communities. The combination of these methods allowed for the triangulation of information, increasing the validity and reliability of the findings (Árva et al. 2022).

This qualitative approach was implemented through the use of different data collection techniques depending on the profile and context of the participants. Individual interviews were conducted with technical and coordination staff, while group interviews and focus groups were carried out in school and community settings to encourage interaction among diverse actors. This strategy allowed us to capture the complexity of the project through multiple voices and strengthened the validity of the analysis through source triangulation.

Table 1 presents the distribution of fieldwork, detailing the total number of interactions conducted through each of the data collection instruments used in the evaluation. This systematisation facilitates data analysis and allows for the identification of key trends in the experiences of project beneficiaries (Leko et al. 2021).

Table 1.

Techniques used.

The research began in January 2022, and fieldwork was conducted between April and July 2022. Much of the fieldwork was carried out in Senegal; specifically, the principal investigator of the GRITS research group (Research and Innovation Group in Social Work) from the University of Barcelona, travelled to each of the territories where the ‘Bikes for Education’ project was implemented, visiting a total of 2 primary schools and 7 high schools. The participants in the evaluation were divided into five main groups: (1) BSF team (Catalan and Senegalese); (2) management, educational, and mechanical teams; (3) families; (4) students; and (5) others. Table 2, below, shows the total number of participants distributed among the different groups of people. A total of 80 people participated.

Table 2.

Participants according to identified groups.

French is the official language of Senegal; however, the regions coexist with different national languages Wolof, Serere, Diola, Pulaar, Soninke, and Mandinké (Wehbe et al. 2011). The interviews and focus groups were conducted mainly in French; only in the case of four families was a translator used, because they spoke Serere.

The qualitative analysis was conducted using a deductive structure based on the study’s objectives and guiding evaluation questions. A thematic coding framework was developed to guide both data collection and analysis. This coding was organised into three main categories: (1) contextualization, which included aspects of the educational system, characteristics of and differences between schools, challenges and strengths of students and their families, and perceptions of the project in the rural communities of Fatick and Mbour; (2) project evolution (2015–2022), addressing elements such as implementation in schools, the role of teams in Catalonia and Senegal, engagement with teaching staff, challenges and achievements, and the monitoring and evaluation system; and (3) project benefits, grouped into educational, social, economic, community, and spiritual dimensions. This structure enabled a comprehensive and comparative reading of the experiences gathered across the different territories.

The results obtained in the interviews and focus groups were transcribed and then translated into Spanish, in order to unify the languages and facilitate the understanding of the content for the entire research team. Subsequently, the transcripts were coded, using deductive coding and identifying different categories: education system, perception and need, project evolution, and project benefits. From these, further subcategories of analysis were defined to further deepen the content. In order to proceed with the analysis of the fieldwork, a content analysis (Bardin 1996) was carried out, which allowed us, based on the results, to formulate inferences applicable to the context and draw conclusions (Krippendorff 1980). The analysis of the results was carried out between September and December 2022, and a first extensive report was then produced for internal use by BSF.

In order to comply with ethical guarantees, an informed consent document was drawn up in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the protection of personal data and the guarantee of digital rights.

3. Results and Discussion

From the analysis of the data obtained, five key dimensions of the impact of the ‘Bikes for Education’ project were identified: (a) educational impact, (b) gender equity, (c) economic effects, (d) community transformation, and (e) religious impact. These dimensions are summarised in Table 3 and constitute the structure of the following section, which presents the most relevant findings and discusses them in relation to existing literature on access to education in rural contexts and the role of Social Work in international cooperation.

Table 3.

Summary of thematic content analysis.

3.1. Educational Benefits

The findings suggest that the project has generated substantial improvements in school attendance and punctuality. The narratives of students, teachers, and project coordinators highlight how the availability of bicycles has reduced travel time, allowing students to arrive in better physical and mental conditions for learning.

One of the testimonies highlights that ‘Now the pupils arrive. And they arrive earlier at school. School performance has increased a lot’ (BSF_CoordinatorBSF-Senegal-190422). Similarly, the management of the Lycée Palmarin emphasises the reduction in absenteeism and tardiness, particularly among baccalaureate students.

According to previous studies, initiatives that facilitate school mobility have shown a positive impact on the retention and academic performance of students in highly vulnerable contexts (Dieng Diasse and Kawai 2024; Lenz and Shier 2021). The results obtained reinforce this evidence, as the testimonies collected suggest that the reduction in travel time has allowed students to spend more time studying and resting, which translates into better academic performance. ‘But nowadays, they have enough time to learn (…) This means that you don’t lose time to rest and learn’ (STA_Accountant-LycéePalmarin-190422).

The regularity of attendance and the better physical conditions with which students arrive at school have had a positive impact on academic performance. ‘And in terms of academic performance, a student who was often late is now no longer lagging behind’ (STA_Direction-LyceéPalmarin-270622). The ease of getting to school by bicycle helps students conserve their energy for learning, which is reflected in their grades. ‘And half an hour longer, they can rest a bit more. And that shows in his grades. He gets better grades’ (FAM_Family3-LyceéPalmarin-280622).

Finally, the project has served as a powerful tool to promote the right to education, especially by decreasing adolescent dropout rates. ‘We have political programmes to encourage, to encourage families to bring all their children to school’ (OTH_ColaboratorBSF- Senegal-130622). By facilitating physical access to education, the project contributes directly to ensuring that more children can exercise their right to learn.

3.2. Gender Equity

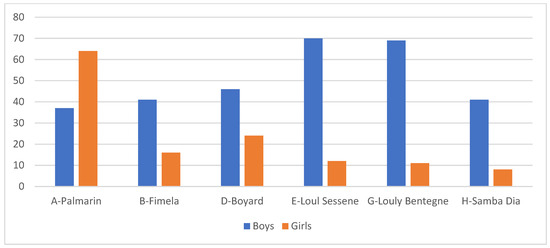

Unequal access to education between boys and girls in rural areas reflects structural and cultural barriers that perpetuate gender inequality (Xaley 2018; Coquéry-Vidrovitch 2021). This study has revealed that the Bikes for Education project has contributed to reducing these inequalities in selected schools, facilitating the mobility of female students and, consequently, decreasing the gender gap in school attendance.

In particular, the data show that in those schools where the project has been implemented for a longer period of time, the proportion of female students benefiting from the project is higher. This suggests that the continued presence of the initiative has not only improved access to education, but has also influenced the transformation of cultural norms about female mobility (Xaley 2018). A project coordinator at Lycée Palmarin highlights this change: ‘Here we have more girls than boys using the bikes’ (BSF_CoordinatorBSF-Senegal-190422).

However, despite this progress, female students continue to face specific challenges that influence their access to and use of bicycles, as can be seen in Figure 1. These include the perception of insecurity in commuting, fatigue from prolonged cycling, and the need to strengthen their autonomy and empowerment. These factors and their impact on the students’ experience within the project are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Gender distribution in each school. School year 2021–2022. Source: own elaboration.

3.2.1. Sense of Danger

One of the main obstacles to mobility for girls and adolescents is the concern for safety on their school journeys. Many students reported feeling vulnerable when cycling, especially on routes with high vehicle traffic or lonely roads (Newman 2019).

However, the use of bicycles has reduced exposure to these risk situations, as it shortens travel time and reduces the need to walk long distances. Despite this, some female students showed initial resistance to cycling, preferring to travel in groups. Over time, their perceptions changed and they began to see the bicycle as a tool that not only facilitates access to education, but also improves their safety and efficiency of travel (Benson 2020; Leone et al. 2022).

3.2.2. Fatigue and Efficient Cycling

‘In the past, a girl who walked about four kilometres, sometimes running so as not to be late, would arrive sweating. The sweat indicated that she had expended a lot of energy. Imagine how he felt when he arrived at school. Sometimes she was exhausted. That had a negative impact on his ability to concentrate and participate in class’ (OTH_ColaboratorBSF-Senegal-130622).

Continuous use of bicycles raised concerns related to fatigue, especially towards the end of the school cycle, as adolescent girls were already menstruating. However, care and attention to bicycle maintenance were observed among female students, resulting in a lower breakdown rate compared to male students. These findings suggest the need to adapt project implementation strategies to maximise impact and sustainability (Salat et al. 2021; Oliveros-Romero and Aibinu 2023).

3.2.3. Empowerment and Autonomy

Access to their own means of transport contributed significantly to the empowerment of female students, allowing them to better organise their time and reduce their dependence on family members for travel (Oliveros-Romero and Aibinu 2023). This not only improved their academic performance but also strengthened their self-esteem and perception of autonomy. The bicycle became a symbol of freedom and the ability to overcome structural barriers that traditionally limited girls’ access to education (Gadaire and Kilmer 2020; Koddenbrock et al. 2022).

3.3. Economic Benefits

The bicycle project, although initially met with resistance from some families due to the payment required to participate in the project, proved to be a significant source of economic savings. One of the most notable advantages is that the cost of the bicycles is lower than that of private transport, which translated into a direct benefit for the families. As the Accountant-LycéePalmarin (STA-190422) points out, children usually spend around CFA 200 a day on transport, which, when considering a school month with 20 days, adds up to a total of CFA 4000. This figure represents a considerable amount of money that can be saved by using bicycles as a means of transport. These findings are in line with studies on school mobility and household cost reduction in rural contexts, which show that the provision of bicycles contributes to a decrease in transport expenditure and facilitates a better distribution of the household budget (Dieng Diasse and Kawai 2024; Oliveros-Romero and Aibinu 2023).

However, it is important to bear in mind that financial savings are not only limited to transport. There is also the cost of the canteen to consider, as the children cannot return home in time for lunch: ‘many families spend around 500 francs every morning to cover the cost of transport and food for their children. This means that the bicycle project not only reduced transport costs, but also provided the opportunity for children to return home for lunch, which meant additional savings for families (STA-Accountant-LycéePalmarin, 190422). In line with this, the FAM_Familie3-LyceéPalmarin-280622 states ‘in an environment with multiple people and expenses, not having bicycles means spending 500 francs a day, of which 200 for transport and 300 for food’. Reducing this expenditure has been identified in other studies as a determining factor in improving the living conditions of vulnerable families, allowing these resources to be allocated to other essential areas such as food, health, and education (Salat et al. 2021; Lenz and Shier 2021).

This discourse was also confirmed by the BSF administrative officer from Senegal (STA-020422), who was also a beneficiary of the project: ‘before the arrival of the project, families had to provide a considerable amount of money to cover both transport and lunch for their children on a daily basis’. However, with the implementation of the bicycles, these expenses were drastically reduced, easing the financial burden on parents. This reduction in overhead costs provides financial relief to families and allows them to allocate those resources to other needs (McRoberts et al. 2024).

As mentioned above, it is important to highlight that, despite the economic benefits that the bicycle project brings to many families, there is a group of particularly vulnerable families, sometimes referred to as ‘social cases’, who face difficulties in affording the fee required to participate in the project. This issue has come up recurrently during the fieldwork and has been identified as a significant challenge in all schools. Previous studies have shown that without financial inclusion measures, projects can reinforce existing inequalities rather than mitigate them (Amin et al. 2022). As one interviewee put it: ‘You can’t pay for social cases. I think it is interesting to know (…) The project should think about how to do it (…) because these are social cases and, in this way, we help people who have more needs’ (OTH_HeadStudies-Mechanics-LycéeBoyard-300622).

The Bikes for Education project has been proven to be an effective strategy to reduce household costs associated with education and improve access to school opportunities. However, its implementation should consider complementary strategies to ensure the inclusion of the most vulnerable households and avoid the reproduction of economic inequalities within Senegal’s rural education system (Seye Djité and Diakhate 2019; Leone et al. 2022). The creation of subsidy or solidarity funding mechanisms would maximise the impact of the programme, ensuring its sustainability and equity of access for all beneficiary families (Daff et al. 2019).

3.4. Community Transformation

The bicycle project in Senegal, beyond its direct educational and environmental benefits, had a significant impact on the community, transforming mobility and employment. This initiative challenged and reshaped entrenched cultural perceptions of cycling, promoted environmental sustainability, and created employment opportunities.

3.4.1. Cultural Transformation and Community Acceptance

Initially, the bicycle was not considered a viable means of transport in Senegal, perceived rather as a leisure object of no practical use. However, the implementation of the project in Palmarin marked a turning point. ‘Carrying a bike is not culture, it is not part of the Senegalese culture… But in Palmarin we’ve moved past that’ reflects how the community overcame old perceptions, integrating the bicycle into their daily lives.

Community acceptance of the project has spread among students, families, and educational teams, underlining the importance of education and its influence on social upward mobility. A former project collaborator notes that ‘Not only have the parents accepted the project, but the students have also embraced it’, demonstrating the project’s comprehensive impact on the education community and alignment with local values about education. Previous research has shown that community participation and cultural ownership of mobility initiatives can be key to their long-term sustainability (Mitlin and Satterthwaite 2013).

3.4.2. Environmental Benefits and Cultural Change

Although the environmental impact of cycling was debated in the context of Senegal, where mobility traditionally did not rely on motorised vehicles, the project fostered a cultural shift towards more sustainable lifestyles. The bicycle, initially viewed with scepticism due to its comparative environmental impact, gained acceptance as a viable and environmentally friendly alternative to solve everyday problems and as an efficient means of transport for the educational community and beyond.

3.4.3. Employment Generation and Community Empowerment

The project contributed significantly to the local economy through job creation. The hiring of coordinators, mechanics, and other roles within the project not only provided employment opportunities but also empowered the local community. ‘The whole community benefits from this project… it creates jobs’ noted the importance of the initiative in economic strengthening and local capacity building.

From a community economic development perspective (Blakely and Leigh 2013), the generation of local employment from sustainable infrastructure projects strengthens economic autonomy and builds community resilience. Accordingly, the training of mechanics and the creation of maintenance structures not only ensured the sustainability of the project but also facilitated the transfer of valuable technical skills.

3.5. Impact on Religious Practice

The project has been proven to be a catalyst for social and cultural change by facilitating access to religious education, a key element in the intergenerational transmission of values and the consolidation of a sense of community. Improved mobility has enabled more children and young people to regularly attend spaces for spiritual formation, strengthening their bond with their religious community and favouring the continuity of their education in values. Several studies have pointed out that accessibility to religious education is essential for the maintenance of cultural identity and social cohesion, especially in contexts of religious diversity (Diallo et al. 2023).

This is reflected in the testimony of a Christian mother in Palmarin:

“For us Christians it is necessary, it is necessary to make communion to receive the body of Christ. Yes. I didn’t know there were such problems. Because the priest is the first. Before making communion. They are obliged to study, to go to catechism from October to May or June. Your child must learn catechesis. She will inform mom or dad. I go to the points game”(STA_AdministrativaBSF- Senegal-020422)

A notable aspect of the project has been its impact on overcoming mobility barriers that have historically limited access to religious education. In particular, the bicycle has served not only as a means of transport to school, but also as a tool to ensure students’ participation in their spiritual formation. Previous research has shown that mobility has a direct impact on the continuity of value education, as distance and transport difficulties often represent significant obstacles to regular attendance in these learning spaces.

In rural communities in West Africa, the lack of transport infrastructure remains a critical challenge for access to education, including religious formation in catechesis and other faith-based learning spaces. These constraints affect regularity of attendance and, consequently, continuity in the transmission of religious values (Banco Mundial 2022). Different studies have highlighted that mobility is a key factor in educational participation, as it allows for the inclusion of traditionally marginalised sectors in religious and community formation processes. Moreover, in a context where religion plays a central role in social cohesion, the possibility of attending ceremonies, community gatherings, and spiritual events reinforces the sense of identity and belonging. This impact goes beyond the individual, as it consolidates support networks between families and favours a more enriched inter-religious coexistence (UN-Habitat 2016).

In this framework, the project has contributed significantly to ensuring greater access to educational spaces, reducing the mobility gap that has historically limited the participation of children and young people in catechetical activities. As expressed by a testimony collected in the community: ‘For us Christians it is necessary to make communion… they are obliged to study, to do catechism’, reflecting how access to transport directly influences the practice and transmission of religious values. The relationship between mobility, access to education, and continuity in spiritual formation has been extensively documented in studies on community development and sustainability in West Africa (Lausanne Movement 2022).

4. Weaknesses and Recommendations

These recommendations seek to address the identified challenges and enhance the impact of the ‘Bikes for Education’ project. The implementation of these improvements contributed to the increased effectiveness and sustainability of the project, promoting access to education and the empowerment of rural communities in Senegal.

Several weaknesses were identified that require attention to optimise the impact and effectiveness of the programme. The areas for improvement are presented below, along with corresponding recommendations to address them.

4.1. Sufficient Data Collection

The evaluation revealed a lack of systematic and detailed data that prevented a thorough analysis of the project’s impact on students’ academic performance and learning. While numerous interviews were conducted with key stakeholders such as teachers, families, and institutional representatives, it would still be necessary to broaden and diversify the sample and to complement these data with specific statistics on attendance, retention rates, and academic performance.

Recommendation: Implement a comprehensive data collection system, including quantitative and qualitative indicators, to assess the academic and social impact of the project. This will allow for evidence-based adjustments to continuously improve the project.

4.2. Systematised Expansion Needs

Project expansion was observed without a coherent diagnosis of new schools, which could lead to an inefficient allocation of resources.

Recommendation: Maintain a rigorous and systematic process for the identification and selection of new schools, ensuring that those with the greatest need and potential for impact are prioritised.

4.3. Economic Challenges of Vulnerable Families

Some families faced extreme economic hardship that limited their ability to participate in the project, widening the education gap.

Recommendation: Allocate funds to subsidise the cost of bicycles for particularly vulnerable families and consider including a Social Worker to support these families, ensuring that the project reaches the students who need it most.

4.4. Gender Inequality in Access to Education

Despite efforts, gender barriers still persist that affect equal access to education for girls and adolescent girls.

Recommendation: Implement specific strategies to address and overcome gender barriers, including awareness-raising campaigns and actions aimed at empowering female students, their families, and the community to promote a safe environment for their participation.

4.5. Adequate Storage Infrastructure

The lack of adequate storage infrastructure for bicycles during holiday periods puts their maintenance and availability at risk.

Recommendation: Expand and improve the infrastructure of workshops and storage spaces in schools, ensuring that bicycles are secure and in optimal condition for continued use.

5. Conclusions

The evaluation of the Bikes for Education project reveals more than a success story in improving school access; it is a testament to the transformative power of development interventions that are deeply embedded in the cultural, economic, and social realities of the communities that they serve. While the project was initially conceived as a means to facilitate educational access through the provision of bicycles, its impacts reverberated far beyond this objective, touching dimensions as varied as community identity, gender dynamics, economic stability, and even spiritual life.

This case exemplifies the potential of simple, context-appropriate innovations to unlock complex chains of positive change. Bicycles—commonly overlooked in development discourse—became not only tools for mobility but also instruments of empowerment, particularly for adolescent girls, whose participation in education was often constrained by systemic and cultural barriers. Through the bicycle, students gained not only time and energy but also a renewed sense of dignity, autonomy, and possibility.

A particularly relevant outcome of the project was its contribution to gender equity. While the programme was open to all students, the evaluation uncovered the specific ways in which girls disproportionately benefitted—once initial barriers such as safety concerns, fatigue, and domestic responsibilities were addressed. The involvement of educational staff and families was key in generating awareness of these challenges and progressively shifting perceptions. By shortening commute times, improving safety, and reducing the caregiving burden on mothers, the bicycles helped promote girls’ continuity in school and alleviated long-standing structural inequalities. The fact that, in some schools, more girls than boys were eventually using bicycles is not only statistically significant—it symbolically underscores a reversal in access norms and an opening for broader gender transformation.

One of the most striking insights from this evaluation is the way in which the project fostered cultural and symbolic change. In communities where cycling was previously marginal or even stigmatised, its integration into daily life came to represent a broader shift in how education, childhood, and progress are understood. The bicycle became a shared language through which families, schools, and students could reimagine their futures—more connected, more sustainable, and more equitable.

The project’s success was not only in its outputs—such as the number of bicycles distributed or schools involved—but in its processes and relationships. The active participation of stakeholders across two continents, the collaboration between educators, families, and technical teams, and the adaptability of the programme across different phases and local needs all speak to a model of cooperation that is as much about listening and learning as it is about delivering aid. This reinforces the idea that development cannot be imposed; it must be co-constructed with those it intends to serve.

Moreover, the evaluation underscores the interdependence of rights and opportunities. Improved access to education, for instance, also meant improved health, reduced household expenses, greater safety for girls, and the creation of local employment. These ripple effects illustrate the systemic nature of exclusion—and the equally systemic nature of effective interventions. The emphasis should not only be on educational access as a goal in itself, but as an entry point to a more holistic and dignified life.

Finally, the pride expressed by families when their children were selected for a bicycle, and the joy of students who saw their daily journey transformed, speak to something essential: development that resonates at the emotional and symbolic levels is more likely to be owned, sustained, and expanded. Accordingly, Bikes for Education is more than a programme—it is a platform for imagining alternative futures, built on mobility, inclusion, and shared responsibility.

In this study, all participants gave informed consent prior to participation. They were informed about the aims of the research, the nature of their participation, and the confidentiality of their responses. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring respect for the rights, dignity, and autonomy of the participants.

In order to comply with the ethical guarantees, an informed consent document was drawn up, following the Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the protection of personal data and the guarantee of digital rights. All participants received detailed information on the objectives of the study, the methodology used, and the possible impacts of their participation. The written informed consent document was provided in French and Serer, which each participant signed before starting any interview or focus group discussion. In addition, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and request clarification before giving their consent. Consent was collected in written form, ensuring respect for local ethical and cultural codes. It was also ensured that participation was voluntary and that participants could withdraw at any time without explanation or consequence. The data collected were anonymised and treated with strict confidentiality to protect the privacy of the participants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Q.R., M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Methodology, V.Q.R., M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Investigation, V.Q.R., M.A.M. and J.C.-M.; Formal Analysis, V.Q.R., M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Data Curation, V.Q.R., M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, V.Q.R., M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Writing—Review & Editing, V.Q.R., M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Supervision, M.A.M., J.C.-M. and B.P.M.G.; Project Administration, V.Q.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its non-interventional nature, as it did not involve medical or clinical procedures nor the collection of sensitive personal data. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring respect for participants’ rights, dignity, and autonomy.

Informed Consent Statement

In this study, all participants gave informed consent prior to participation. They were informed about the aims of the research, the nature of their participation and the confidentiality of their responses. In order to comply with the ethical guarantees, an informed consent document was drawn up, following the Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the protection of personal data and guarantee of digital rights. All participants received detailed information on the objectives of the study, the methodology used, and the possible impacts of their participation. The written informed consent document was provided in French and Serer, which each participant signed before starting any interview or focus group discussion. In addition, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and request clarification before giving their consent. Consent was collected in written form, ensuring respect for local ethical and cultural codes. It was also ensured that participation was voluntary and that participants could withdraw at any time without explanation or consequence. The data collected was anonymised and treated with strict confidentiality to protect the privacy of the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguiton, Sara Angeli. 2020. A market infrastructure for environmental intangibles: The materiality and challenges of index insurance for agriculture in Senegal. Journal of Cultural Economy 14: 580–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Humera, Helana Scheepers, and Mohsin Malik. 2022. Project monitoring and evaluation to engage stakeholders of international development projects for community impact. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 16: 405–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Árva, Dorottya, Anna Cseh, Ágota Mészáros, David Major, Anna Jeney, Diána Dunai, and Szilvia Zörgő. 2022. A unified qualitative-quantitative method to evaluate the impact of being a near-peer health educator. The European Journal of Public Health 32: ckac131.369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Mundial. 2022. Estrategia de Educación de África Occidental y Central (2022–2025). Washington, DC: Grupo Banco Mundial. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099340006232242518/pdf/P17614904f022b0fe0b0e2039bf7dec0f30.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Bardin, Laurence. 1996. Content Analysis, 2nd ed. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Carol. 2020. An innovative ‘simultaneous’ bilingual approach in Senegal: Promoting interlinguistic transfer while contributing to policy change. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25: 1399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, Edward J., and Nancey Grey Leigh. 2013. Planning Local Economic Development: Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brossier, Marie. 2024. Failed hereditary succession in comparative perspective: The case of Senegal (2000–2024). African Affairs 123: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Pedro, Oswald Koussihouèdé, Nathalie Lahire, Costas Meghir, and Corina Mommaerts. 2019. School grants and education quality: Experimental evidence from Senegal. Macroeconomics: National Income and Product Accounts eJournal 87: 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Robert. 1997. Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First, Last. London: Intermediate Technology Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coquéry-Vidrovitch, Catherine. 2021. Access to higher education in French Africa south of the Sahara. Social Sciences 10: 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespin-Boucaud, Juliette, and Rozenn Hotte. 2021. Parental divorces and children’s educational outcomes in Senegal. World Development 145: 105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daff, Bocar, Serigne Diouf, Elhadji Sala Madior Diop, Yukichi Mano, Ryota Nakamura, Mouhamed Mahi Sy, Makoto Tobe, Shotaro Togawa, and Mor Ngom. 2019. Reforms for financial protection schemes towards universal health coverage, Senegal. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 98: 100–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, Mamadou Abdoulaye, Ngoné Mbaye, and Ibrahima Aidara. 2023. Effect of women’s literacy on maternal and child health: Evidence from demographic Health Survey data in Senegal. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 38: 773–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieng Diasse, Mbaye, and Norimune Kawai. 2024. Barriers to curriculum accessibility for students with visual impairment in general education setting: The experience of lower secondary school students in Senegal. The Curriculum Journal 36: 110–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, Boucar, and Ekra Miezan. 2021. The limits of the concession-led model in rural electrification policy: The case study of Senegal. Renewable Energy 177: 626–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Baldor, Álvaro, and Alejandra Boni. 2011. Evaluación de proyectos de cooperación para el desarrollo. Una contribución desde el enfoque de capacidades. Paper presented at V Congreso de Universidad y Cooperación al Desarrollo, Cádiz, Spain, April 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Vicente Ferrer. 2020. Bicicletas con poder. Únete al reto para evitar que 600 Adolescentes de la India Rural Abandonen sus Estudios. Available online: https://www.fundacionvicenteferrer.org/noticias/bicicletas-con-poder-unete-al-reto-para-evitar-600-adolescentes-de-la-india-rural (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Gadaire, Dana M., and Ryan P. Kilmer. 2020. Use of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist in Social Work research. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 17: 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, Amanda D., Kimberly Y. Huggins-Hoyt, and Joelle Pettus. 2016. Assessing statistical change indices in selected Social Work intervention research studies. Research on Social Work Practice 26: 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Heath. 2021. The moral foundations of impact evaluation. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 23: 425–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Mohamadou Bachir, and Katherine I. Martin. 2023. Teaching EFL reading in Senegal: Current practices and recommendations. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 42: 164–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koddenbrock, Kai, Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven, and Ndongo Samba Sylla. 2022. Beyond financialisation: The longue durée of finance and production in the Global South. Cambridge Journal of Economics 46: 703–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 1980. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lausanne Movement. 2022. El Crecimiento de África y el acceso a la Educación Religiosa. Available online: https://lausanne.org (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Leko, Melinda M., Bryan G. Cook, and Lysandra Cook. 2021. Qualitative methods in special education research. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice 36: 278–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, Trish, and Michael L. Shier. 2021. Supporting transformational social innovation through Social Work practice. Journal of Social Work 21: 248–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, Cortney, Harshavardhan Thippareddi, Cheikh Ndiaye, Ibrahima Niang, Younoussa Diallo, and Manpreet Singh. 2022. Safety and quality of milk and milk products in Senegal—A review. Foods 11: 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quotidien. 2022. Pour le paiement des salaires de 5000 enseignants: Abdou Faty brandit le boycott des cours. Available online: https://lequotidien.sn/pour-le-paiement-des-salaires-de-5000-enseignants-abdou-faty-brandit-le-boycott-des-cours/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- McRoberts, Neil, Samuel Brinker, and Kaity Coleman. 2024. Theories for understanding the effect of impact assessment and project evaluation on the practice of science. Annual Review of Phytopathology 62: 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitlin, Diana, and David Satterthwaite. 2013. Urban Poverty in the Global South: Scale and Nature. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Anneke. 2019. The influence of migration on the educational aspirations of young men in northern Senegal: Implications for policy. International Journal of Educational Development 65: 216–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros-Romero, Jose, and Ajibade Aibinu. 2023. Ex-post impact evaluation of PPP projects from multiple stakeholder perspectives: A toll road case. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 13: 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyekale, Abayomi. 2023. Utilization of proximate healthcare facilities and children’s wait times in Senegal: An IV-Tobit analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz y Desarrollo. 2020. Estrategia País Senegal 2020–2024. Hacia un desarrollo sostenible: Participación activa para disminuir las desigualdades y vulneración de derechos de las personas. Available online: https://www.pazydesarrollo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PLAN-ESTRATEGIA-SENEGAL-Anexo-8.-Estrategia-Pai%CC%81s-Senegal.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Rice, Karen, and Heather Girvin. 2021. Applying intervention research framework in program design and refinement: A pilot study of youth leadership, compassion, and advocacy program. Social Work with Groups 45: 336–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salat, Hadrien, Markus Schläpfer, Zbigniew Smoreda, and Stefania Rubrichi. 2021. Analysing the impact of electrification on rural attractiveness in Senegal with mobile phone data. Royal Society Open Science 8: 201898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seye Djité, Seynabou, and Meissa Diakhate. 2019. Organización del sistema educativo senegalés. MLS Educational Research 3: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, Tim, and Joop de Kraker. 2023. Applying SCALE 3D for evaluating transformative social innovation. Evaluation 29: 428–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundell, Knut, Marit Eskel, Martin Bergström, and Therese Åström. 2023. How can practitioners assess the value of Social Work interventions? Research on Social Work Practice 33: 634–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, Ibrahima, Ansoumana Bodian, Mamadou Konté, Lamine Diop, Papa Malick Ndiaye, Sokhna Thiam, and Joseph Mouanda. 2021. Impact of regional water supply, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) program in Senegal on rural livelihoods and sustainable development. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 12: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. 2016. Informe Regional de África para Hábitat III. Available online: https://habitat3.org (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Walker, Heidi, Jenny Pope, Angus Morrison-Saunders, Alan Bond, Alan P. Diduck, A. John Sinclair, Brendan Middel, and Francois Retief. 2024. Identifying and promoting qualitative methods for impact assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 42: 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, Carmen, Serafin Corral, and Farah Cova. 2011. Senegal 1970–2040: Evolución y Escenarios Futuros. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10071/2395 (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Xaley. 2018. La situación de la Educación de las niñas en Senegal. Available online: https://xaley.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Estudio-situacio%CC%81n-nin%CC%83as-senegal.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).