Abstract

Migration and social transformation are major drivers of socio-economic development. Yet, the linkages between social transformation and migration in Ghana are poorly understood. This article seeks to shed light on how social transformation affects or is affected by migration, using mixed methods with transformationalist and social change theoretical lenses. At the same time, there have been retrogressive transformations in the economic conditions, technology and demography have improved and increased, respectively, and political and cultural factors have remained relatively the same over the past decade. Although there is a perceived bi-directional relationship between social transformation and migration, social transformation exerts greater influence on migration than migration has on social transformation except for higher educational attainment and improved household income. Therefore, the relationship between social transformation and migration is not balanced in our study area as the former influences more than the latter.

1. Introduction

Migration is a common global phenomenon expected to increase (Migration Data Portal 2024; UNDESA 2020). According to the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), global migrants’ stock in mid-year 2020 was almost 281 million, depicting an increasing trend over the years (UNDESA 2020). Within Africa, migration is prevalent and significant. For instance, in 2020, sub-Saharan Africa was the origin and destination for about 28 million and 22 million migrants, respectively. Intra-regional and intra-national migration is more pronounced in Africa as most of the migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, especially West Africa, live in other countries within the continent (Migration Data Portal 2023; Teye 2022; UNDESA 2020).

Ghana, a West African country, epitomes the state of migration in Africa. It is the country of origin, transit, and destination of many migrants (Setrana and Kleist 2022; Teye 2022). Internal migration is also intense and dynamic (GSS 2023). According to the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), 28.9 percent or approximately nine million of Ghana’s total population in 2021 were migrants with females forming the majority (52.5 percent) (GSS 2023). North–South migration is dominant due to a rich flow history in that direction. In addition, rural–urban migration is the dominant form of flow in Ghana and a major driver of urbanisation (GSS 2023).

Migration transforms, and is shaped by, sociocultural, economic, and political structures and processes (Osei-Amponsah et al. 2023). While the transformations of social factors can drive, or be influenced by, migration, earlier empirical studies tend to neglect theoretically relevant non-economic migration drivers such as demographic shifts, political transitions, educational expansion, technological advancements, or cultural change (de Haas and Fransen 2018). Despite increasing rural-urban and north–south migration studies in Ghana, there is still limited knowledge on how other non-economic social changes intersect with migration to drive development in the Upper West and Savannah Regions. There is a need to understand the dimensions of social transformation in our study communities, such as what drives migration, the extent to which migration drives social transformation, and the mobility type that influences social transformation the most. The research questions guiding the analysis of this article are the following: what is the relationship between social transformation and migration and what mobility type significantly influences social transformation in the Savannah and Upper West regions of Ghana? Understanding these is crucial to formulating and advocating for informed migration policies for development in Ghana.

The rest of the article is structured in five sections. Section 2 focuses on the theoretical underpinnings of social transformation, followed by the methods (Section 3). In Section 4, we present the findings on how social transformations drive and are driven by migration. We then discuss the findings (Section 5) before we conclude in Section 6.

2. Social Transformation: A Conceptual Framework

We employ the concept of social transformation as it is suitable for understanding the linkages between societal changes and migration. Social transformation is a complex and sustained change in societal norms (de Haas et al. 2020; Fazey et al. 2018; Schipper et al. 2021). Social transformation can be disaggregated into economic, cultural, technological, demographic, and political dimensions (Castles 2010; de Haas and Fransen 2018; Polanyi 1994). According to de Haas and Fransen (2018), the economic dimension includes the accumulation and use of land, labour, and capital in producing, distributing, and consuming goods and services. The cultural dimension involves beliefs, values, norms, and customs shared by groups. The technological aspect of social transformation is the application of knowledge through procedures, skills, and techniques. The structure and spatial distribution of populations and the organised control of people constitute demographic and political dimensions of social transformation.

According to Castles (2001), social transformation theory recognises the need to understand the ‘interconnectedness, variability, contextuality’ and linkages among different parts of the world. The theoretical underpinnings of social transformation emanate from either the globalisation process or the social change discourse.

Globalisation has contributed to immense interconnectedness and interaction worldwide, significantly impacting how societies are shaped and understood. Globalisation has reduced the distinctions between ‘modern and traditional’, ‘highly developed and less developed’, ‘Eastern and Western’, and ‘the South and the North’ (Castles 2001, 2010). Held et al. (2000) identified three broad perspectives on globalisation, including ‘hyperglobalisers’, ‘sceptics’, and ‘transformationalists’. The most relevant perspective in this study is the transformationalist view, which posits that globalisation is a product of closely interlinked processes of change in technology, economic activity, governance, communication, and culture (Held et al. 2000). According to Castles (2010), many regions of the world have been integrated into the global system due to intensive cross-border flows of migrants, trade, investment, and cultural artefacts, among others.

The social change literature analyses transformation as a type of ‘change’ within its domain. In this regard, social change has been used as an umbrella concept under which transformation is one of the typologies of change. There are several typologies of social transformation. However, we focus on ‘innovation’ and ‘substitution’ (Elster 1983) and ‘adaptation’ and ‘transformation’ (Dwyer and Minnegal 2010). According to Elster (1983, p. 93), substitution is a change in the production process based on existing technical knowledge while innovation is the production of new technical knowledge. Elster’s (1983) theorisation is relevant to understanding how the dimensions of social transformation and migration intersect to drive development. According to Dwyer and Minnegal (2010, p. 632), adaptation change occurs when quantitative and context-dependent shifts occur in variables without substantive alteration to functional relationships between those variables and the contexts within which they are expressed. Transformational change occurs when the relationship between variables alters to elicit qualitative changes in the structure of the ensemble as a whole.

Both social change and globalisation discourses on social transformation are important for this study. Regarding the social change perspective, we relied on Elster’s (1983) typology to identify and explain changes in the study societies relating to ‘substitution’ or ‘innovation’. Additionally, based on the Dwyer and Minnegal (2010) conceptualisation of social transformation, we identify and explain changes in the study societies that are ‘transformational’ or ‘adaptive’. Such a perspective enabled us to discuss qualitative and quantitative aspects of social transformation in the study societies. With specific reference to the globalisation discourse on social transformation, we examine the complex relationships between interactions among people living in different places and changes in technology, economic activity, governance, communication, and culture.

3. Materials and Methods

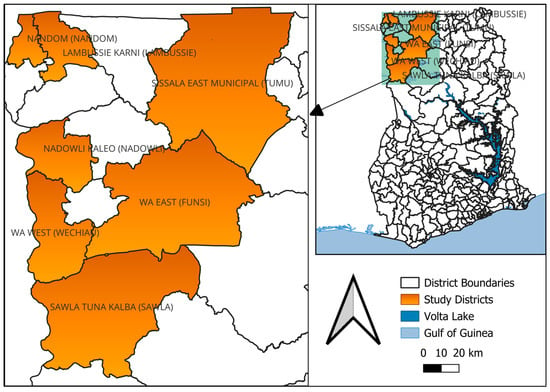

We conducted the study in 21 communities in 7 districts, namely Wa West, Wa East, Sissala East, Lamussie-Karni, Daffiama-Bussie-Issa, Nandom (all in the Upper West region), and Sawla-Tuna-Kalba (STK) in the Savannah region of Ghana as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of Ghana showing the study districts.

The districts are mostly rural. The population growth rate in these regions is less than the national average. Out-migration to cities like Kumasi and Accra for off-farm activities or to the forest zones in the Bono and Ahafo regions is one of the reasons for the slow rate of population growth. All of the districts lie within the Savannah agro-ecological zone and have uni-modal rainfall which supports only one conventional farming season. The main economic activity in the communities is agriculture. With limited or no dams, crop farming is mainly rainfed. Moreover, the temperature is high throughout the year. The regions are more exposed to climate change and its effects on livelihood (Teye 2022).

We employed a mixed-method approach to investigate the effect of social transformation on out-migration, which we define here as the movement of people from their natal homes to places outside their community of origin between the last three months and ten years. To study the issue of migration in the study communities, we combined field-based engagement, quantitative surveys, and qualitative interviews. From May to June 2021, we surveyed 2107 randomly selected households in 21 communities in the study districts. The selected households in each study district are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of households selected from each study district.

We used computer-assisted personal interviewing with CSPro software 8.0.1. The interviews were to explore the effect of social transformation along multiple dimensions on out-migration, and how out-migration affects social transformation. The structured survey questionnaire included questions on the nature of the migrant in terms of gender, education, reasons for migration, and destination.

Additionally, over 100 qualitative interviews were conducted, of which 71 were households, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions (FGD) in the districts of origin, and the rest were interviews with migrants from the selected districts in the Bono and Ahafo regions (15) and in the Greater Accra region (19). All of the transcripts were coded to enhance anonymity. The in-depth interviews included questions on social transformations in the structured survey questionnaire to support the correlation analysis of responses. The social transformation questions that captured perceived changes over a decade were (i) economic changes, (ii) technological changes, (iii) political changes, (iv) demographic changes, and (v) cultural changes. Respondents were asked whether they perceived these dimensions of social transformation to be improving, worsening, or remaining the same.

4. Results

Using the theoretical lens of globalisation and typologies of social change, we found that although economic, technological, and demographic conditions have changed significantly over the past decade and contributed to out-migration, political and cultural factors have largely remained unchanged, exerting limited influence on migration. Migration exerts a limited effect on social transformation in the study areas except for higher educational attainment. Finally, there is a stronger link between social transformation and out-migration than with in- and return migration. Before we delve into these findings, we first explore some socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, the state of out-migration in the study communities, and the socio-economic background of migrants.

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Data on the educational attainment of respondents are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Educational background of respondents.

Table 2 shows that more than 50% of our respondents have no formal education and less than one percent have attained tertiary education. For the respondents who have formal education, most of them completed junior high school (JHS) which is nine years of education.

Furthermore, the marital status of respondents is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Marital status of respondents.

Table 3 shows that most respondents are married, with almost 70 percent in monogamous unions. About 13 percent of our respondents are in a polygamous union. Also, about 10 percent have lost their spouses. More than 95 percent of them are females.

We also asked about the size of the selected households. Household size has implications for livelihoods as it determines, for example, household labour and food demands. The sizes of the households are grouped and presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Household size.

Table 4 shows that the household size of 4–6 people dominates across study districts. Sissala East district has the highest number of households with a size of 10 or more people, with Daffiama/Bussie/Issa having the highest household size of 4–6 people.

4.2. Incidence of Out-Migration, Educational Background of Migrants, and Reasons for Migration

4.2.1. Incidence of Out-Migration

Our survey revealed that the Wa East and Sawla-Tuna-Kalba (STK) districts had the highest proportion of household migrants who moved temporarily or permanently away from the village/town in the last decade (about 40 percent each on average). This is followed by Nandom (about 39 percent), Wa West (about 36 per cent), and Lambussie-Karni (35 percent). The districts with the lowest out-migration rate were Daffiama-Bussie-Issa (about 21 percent) and Sissala East (19 percent).

Our result agrees with the migration report of the 2021 Ghana Population and Housing Census. This result supports other studies and the nationwide census data of the Ghana Statistical Service about the intensity of rural–urban and north–south migration in Ghana (GSS 2023).

4.2.2. Level of Educational Background of Migrants Before Migration

The highest level of education of migrants at departure is reported in Table 5 by gender. There are slight differences in the distribution between males and females with about 44 percent of male and 45 percent of female migrants having no schooling or not completing basic education but having some nursery or primary education. About one in five of the males and females completed basic education. A similar proportion of both males and females completed secondary education. Notably, 4.3 percent of males and about one percent of females had completed bachelor’s degrees before outmigration. At 10 percent, it was also observed that the level of education of a migrant and gender were significantly correlated (χ2 = 21.6526, p = 0.017).

Table 5.

The highest level of education of migrants at departure.

Table 5 also shows that while more females than males have basic education, males have higher education than females. A key informant confirmed that ‘most of them [migrants] are school dropouts and JHS and SHS graduates’ (OKonKAm09). It also emerged during the female FGD in one of the communities that

The level of education of migrants varies from individual to individual…some of them have no educational background …[while] some have completed Junior and Senior School, and some are degree, HND or diploma holders. So, the level of education varies from individual to individual.(OKonFGf1)

It is evident from the data that most migrants spend less than ten years in the formal education system.

4.2.3. Reasons for Migration

Our study revealed that a lack of jobs at the origin, employment opportunities elsewhere, lack of access to higher educational facilities, and hustling are the main causes of migration, as shown in Table 6. For males, finding employment opportunities elsewhere was one of the main reasons (43 percent). Two related reasons were hustling for opportunities (39 percent) and a lack of work in the origin village/town (19 percent). About 20 percent of the males mentioned education as the main reason for migrating. For females, these three reasons were also important for migrating. An additional reason for the females was marriage (28 percent). About 21 percent each of males and females migrated to further their education.

Table 6.

The most important reason for migrating by gender of the migrant (multiple responses).

The qualitative interviews also revealed complex reasons for migrating from the study communities. During a FGD at Bugubelle, participants related the following:

People migrate frequently from this community to places like Accra, Techiman, Kumasi and other galamsey (illegal mining) communities to search for employment. Our main occupation is farming, and we have only one season here. So, many people normally migrate from this community to places where they think they can get some work to do during the off-farming season. Most of them return to prepare their land for the next farming season when the rains are about to start… Poor harvests also influence people’s decision to migrate. When the harvest is bad because of drought or flooding, people migrate to search for jobs.(OBugFGf03)

During another female FGD in the same community, participants unanimously also said the following:

There is no better work here in the community, after the farming season, there is nothing better they have to do here, and the foodstuff won’t even reach the next rainy season again as well, so if they want to stay in the community hunger will kill us all, when they travel to work, and they get money and send [us] even 5 Cedis, [we] can use it to support [ourselves] or even buy bathing soap…when they [the youth] farm and don’t get enough farm products or yields, they have to find additional source of income if not we will sell the small produce we got from the farm and in a short period we won’t get food to eat again. When we all stay here, we may eventually fight.(OBusFGf06)

In Zimoupare, a migrant’s mother narrated why her daughter dropped out of school and migrated. She said the following:

Because we could not care for her through school, she migrated. If someone had supported her through school, she might not have migrated. When she wanted something, I didn’t have the money to buy it, so she left school and migrated. When she was here, we were 9 in the house, five females and four males including my husband me and the children, none of us was working until I got employed in the school [as a cook] but my salary was not coming. My husband was the only one working and caring for all our needs and wants.(OZimMHf12)

The reasons for migration support the findings of Teye (2022) and attest to governance, unbalanced development, and environmental factors in the Upper West region. Migration is complex and people do not move for one reason. van Hear (1998) categorised reasons for migration into underlying, proximate, and precipitating factors. For instance, while drought could be an underlying driver, failing production and conflict could be proximate and precipitating drivers.

4.2.4. Destination and Connections of Migrants

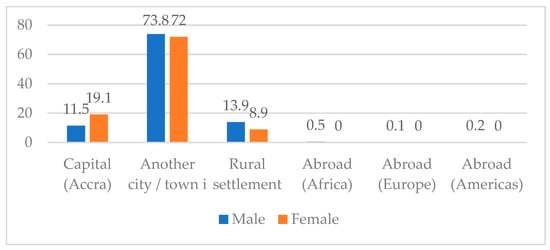

The study revealed that cities are the main destinations of migrants, indicating the prevalence of rural–urban migration. Almost 90 percent of migrants in Ghana move to cities. The distribution of migrant destinations by the gender of the migrant is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The distribution of migrant destinations by gender of the migrant.

About 74 percent of the males migrated to other towns or cities, while 14 percent targeted other rural localities and 11.5 percent travelled to the capital city, Accra. A few (less than one percent) migrate to other African countries or outside Africa. For females, about 72 percent migrate to other cities or towns, 19 percent to Accra, and the rest (about nine percent) to other rural destinations. Due to the concentration of social amenities in cities, especially Accra and Kumasi, and other regional capitals, many migrants are pulled to these areas as found by other studies (Turolla and Hoffmann 2023). It is important to note that, while almost the same percentage of men and women have migrated to other cities, there are differences regarding Accra and rural areas as migrant destinations. Whereas more females than males migrate to Accra, fewer choose rural areas as their destination. A Chi-square test of the different destinations between males and females was significant at a one percent level.

Interviews with migrants also support the quantitative data. A male migrant in Amasaman, Accra gave the reason for his deciding to migrate to Accra as

‘It was because I had a job here in Accra and had to move. Also, I had a friend here so, he was part of the reasons why I moved’.(DAmam14)

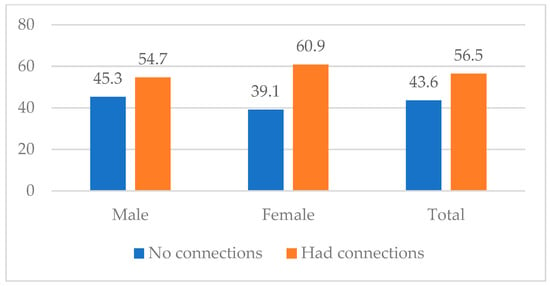

The quotation from DAmam14 underscores the importance of networks in migration decisions. Many migrants move to a destination where they have a social network, as found in other studies (Serbeh and Adjei 2020; Turolla and Hoffmann 2023; Zaami 2020). As shown in Figure 3, more female migrants tend to have a connection before moving (61 percent) compared to male migrants (55 percent). This is understandable because females require more security before moving compared to males. For instance, there are rare cases of male migrants being raped or trafficked for prostitution, so men can migrate to places where they do not have an established network, but women are always careful not to take too many risks.

Figure 3.

The distribution of migrants with connections before moving by gender of the migrant.

Another male migrant narrated how he leveraged a social network to migrate. He said the following:

A friend in this town (Atebubu) informed me that I could get enough land for farming. We were together in Tuna, he earlier left and was engaged in fishing in Yeji but stayed in a town close to Atebubu. He facilitated my movement.(DAtem02, 57 years)

4.3. Perceptions of Migration and Social Transformation

4.3.1. Perceived Effects of Social Transformations on Out-Migration

Table 7 shows changes perceived by respondents in social transformation. While labour availability, capital, and income levels have reduced significantly, access to education and electricity has increased. Conflict, social media, traditional norms, and cultural beliefs remain unchanged.

Table 7.

The direction of change in dimensions of social transformation (percent).

This finding was further explained during a male FGD at Bugubelle where participants said the following:

The income we get from agriculture is very low, and this has forced many people to migrate from this community to other places to search for alternative sources of livelihood, such as illegal mining. Also, there is a shortage of agricultural land for cultivation. The land in this community is fixed, but the population keeps increasing. So, there is a high demand for land. Unfortunately, the land is not enough for the growing population. The land has also lost fertility and cannot support crop cultivation.(OBugFGm04)

Further, respondents perceive that social transformation drives out-migration. Generally, declining economic factors are perceived to cause out-migration, while cultural changes do not affect migration. About 44 percent and 64 percent of respondents felt that the non-availability of farming land and decreasing income levels, respectively, contributed to the increasing out-migration. During a male FGD in Sentu, participants said the following:

Yes, the increase in population has forced some youth into migrating out to the south for farming. If the number of males keeps increasing in a family, there will be a time when the land will not be sufficient for all of them to farm. So, some youth of such families have migrated.(OSenFGm08)

A 27-year-old male migrant living in Accra narrated how the economic element of social transformation contributed to his migration. He said the following:

I migrated to Accra because I felt like the income levels in Accra would be higher…I also felt that there were a lot of jobs that could only be found in Accra and not in the Upper West. Moving too, has been one of the best decisions I have made.(DAccm08)

Accra, the capital city of Ghana, has most of the social amenities and is the locomotive of the formal and informal non-agricultural economy. This is why a migrant said that ‘the cake is in Accra’ (Turolla and Hoffmann 2023). Furthermore, the head of a migrant household in Bulenga also revealed the changes that happened in the past decade and the ambitious nature of people in the community towards migration. He said the following:

In those days, we were not as ambitious as we are today. We were content with the small that we had. We aimed to feed the family; once you were satisfied, that was okay…Those days, we lived in mud houses. We used sticks to construct and covered it with mud, including the roof. We moved to construction with bricks, like the one you see (pointing to a wall). We have moved to blocks and need to buy cement to build nice buildings. Because of that mindset, if someone gives me GHc50,000.00 or even more, I will look at it and ask myself; can I put up some nice building or get a car with that amount? You see, that money will not be enough. Because of that, everybody is now trying to educate their children so they can become big men or big women in society. That requires them to migrate [to work and earn more money]. Some also migrate to mining communities to engage in mining for quick money and when there is an opportunity, to migrate to Europe and America, we do not hesitate at all.(OBulMHm07)

This quotation shows how the quest for decent housing, which enhances social status and standard of living, contributes to migration. Our study also revealed that improvements in infrastructure, such as roads, have facilitated out-migration. Participants of a female FGD at Bugubelle said the following:

Compared to now it was difficult to access means of transportation to easily travel to other places due to the poor nature of the roads. Even now, though the roads are bad, it is better. These days too, there are a lot of vehicles that aid people in travelling to their places of destination(OBugFGf03).

It is important to note that some social transformations do not necessarily drive migration as perceived by our respondents. For instance, more than half of the respondents perceived that access to electricity (64 percent), social media (65 percent), and the mechanisation of agriculture (67 percent) did not affect out-migration. About 78 percent felt that there were no conflicts to drive out-migration. These findings illustrate the complex relationship between migration and social transformation. The lack of effect of these changes on out-migration demonstrates that factors such as social media, the mechanisation of agriculture and electricity are not compelling for people to migrate.

4.3.2. Perceptions of Effects of Out-Migration on Social Transformation

Out-migration could also have effects on some aspects of social transformations. The respondents’ perceptions of these effects are reported in Table 8. In the view of the respondents, the majority of the listed aspects of social transformation are not affected by out-migration. However, about half of the respondents felt that out-migration was decreasing the availability of capital (48.7 percent) and income levels (48.3 percent). About 40 percent also felt out-migration was worsening the availability of labour for production/farming. Most importantly, 47 percent perceive out-migration as enabling people to access education. This is unsurprising as the study communities are rural, with no higher education facilities.

Table 8.

Effects of migration on dimensions of social transformation (multiple responses).

Our qualitative interviews give a deeper insight into the effects of out-migration on social transformation. One of the migrants interviewed said the following:

… if you have been to my village before, you would realise it is not easy to survive there. My family would have been economically worse off if I had not migrated from my hometown. We would not have enough money like what I am getting here from farming and being able to cater for the family expenses. I have been able to build a 4-bedroom house here using [cement] blocks, hardly will you see a block building in my village…So far, migration has been good. It is not even advisable to stay where you were born and grow and die without migrating.(DAtem02, 57 years)

Other effects of migration on social transformation came to light during a men’s FGD at Busie, and participants said the following:

There has been great difference, earlier, you go to the farm to carry sticks on your head to come and roof your house. But through emigration, the youth are now building beautiful houses…Some, when successful, buy cars and come back. One came with a tractor, and he is helping us, if you were originally ploughing manually and you could only cultivate one acre, now as he is here with a tractor and you can cultivate 4 acres, sometimes he does the ploughing for [us] and [we] pay him after harvesting.(OBusFGm05)

Thus, migrants send resources to their communities of origin, which contributes to transforming their households and the society at large. Migration has contributed to technological advancement and the mechanisation of agriculture. This finding agrees with Etwire et al. (2017), who revealed how local people in Northern Ghana leverage mobile technology to access improved and updated agricultural information for climate change adaptation. In addition, thatch houses are becoming rare in the study communities, and people have improved their housing.

The respondents were asked to specify the type of migration or mobility which influenced social transformation. The responses are reported in Table 9.

Table 9.

The distribution of the mobility types influencing dimensions of social change (multiple responses).

Generally, a higher percentage of the respondents felt that out-migration affects most social dimensions compared to in-migration or return migration. For instance, 82 percent of respondents indicated that there is a stronger relationship between availability of capital to a household and out-migration. In other words, out-migration contributes to diversifying household income and providing additional resources to increase household capital, which is reflected in the income level. It is important to note that aside from traditional beliefs and cultural norms/values, all of the dimensions of social transformations are influenced by out-migration in our study communities.

5. Discussion

The findings show that many households in our study communities have a member staying outside the communities of origin. Women, men, and the youth have all leveraged migration to pursue their socio-economic aspirations. The economy is a main factor of migration in our study communities. Migration is a livelihood strategy to diversify earning sources, even when higher earning is not assured, and there is potential job security at the destination. Our finding reflects the observation by Steinbrink and Niedenführ (2020), who noted that migration is a livelihood strategy in West Africa. Many people have migrated to find better job opportunities and have access to higher education. Thus, just like in other studies from the Upper West region, migration is empowering and emancipating people by allowing them to play an active part in negotiating their roles, rights, and responsibilities and contributing financially to the well-being of themselves and their households. Further, as Castles (2010) argued, the reasons for migration are complex and are hardly only economic. Education and marriage also play significant roles in migration. Most rural communities in Ghana, if not all, have no tertiary educational institutions. These institutions are mainly situated in urban centres, so it is imperative for rural people who want to further their education to migrate to the cities. Also, in Ghana, marriages require the bride to move to join the groom. At the same time, population increase is causing farmland sizes to decrease, a major source of livelihood, contributing to out-migration.

Migration in our study communities is largely driven by social transformation. de Haas and Fransen (2018) note that the key transformations inter alia include the growth and spread of industrial capitalism (economic transitions), the mechanisation, standardisation, and automation of techniques and procedures of production and service provision (technological change), national state formation (political change), demographic change and urbanisation (demographic transitions), and rationalisation and individualisation (cultural change). Economic factors, specifically declining income and access to capital, improved technology for skills through education, and demographic change (population increase, high fertility, and urbanisation) are the major changes in our study communities that contribute to out-migration.

Social transformation is the process and outcome of globalisation. From the perspective of the globalisation theory, social transformation regarding technological adoption emanates from the interconnectedness and interaction between migrants and their communities of origin. Global challenges like COVID-19 interrupted the supply chain of goods and services and affected the flow of fertilisers to Ghana. These have increased the prices of imported farm inputs, negatively impacting farmers’ income and contributing to out-migration. Furthermore, through migrants, study communities have gained exposure to technology and information, blurring the boundaries between rural and urban communities in Ghana. The communities are becoming globalised, especially in modern housing architecture that migrants send, finance, or build in the natal communities. Following Dwyer and Minnegal (2010), our study communities are undergoing transformational changes through the closely interlinked processes of change in technology, economic activity, and communication.

Although there are some substitution and innovative changes, as some people are replacing traditional farming methods with mechanised systems, and adopting social media, such changes are limited in our study areas. These transformational, substitutive, and innovative changes have contributed to or influenced out-migration. According to Castles (2010, p. 1576) “social transformation includes intensification of agriculture”. Increasing population requires that agriculture is intensified for high yield. Yet, soil fertility has decreased, requiring the application of fertilisers. Many households leverage migration to earn non-farm income to invest in agriculture. Thus, agriculture mechanisation, supported by remittances, is encouraging more migration. Our study, therefore, supports the argument that there is a recursive relationship between migration and social transformation in that social transformation influences and is influenced by migration (Faist et al. 2018; Castles 2010). While economic, technological, and demographic changes are perceived as the major drivers of out-migration, cultural and political factors have not changed significantly, having limited effect on out-migration. Thus, social change is ‘micro- and meso-processes’ affecting individuals, immediate surroundings, communities, and regions (Portes 2010, p. 1593). Social transformation strongly influences out-migration, as major changes, like decreasing farmland size, limited access to capital, declining income, population increase, and urbanisation, pressure local resources, discouraging in-migration to communities of origin.

Examining the relationship between migration and social change, Portes (2010) contends that migration affects the social structure and social institutions and that the transformative potential of contemporary migration is limited. Our findings also show that increasing educational attainment and migrant household income improvement and housing mainly influence migration in our study communities. Our study, therefore, supports Portes (2010) observation that, for origin societies, migration may strengthen or stabilise the existing socio-political order rather than transform it. Again, unlike Levitt’s (1998) study of Dominican migration to the United States, which revealed that sending towns and regions in the Dominican Republic have been culturally transformed, most people in our study areas do not see significant cultural and political transformation by migration. Perhaps, unlike the Dominican case, which focused on international migrations, most of the migrants in our study areas are internal migrants. As such, there is limited opportunity for foreign culture to be remitted to the communities of origin.

6. Conclusions

We sought to understand the incidence of out-migration, social transformations, and their role in migration in seven districts in the Upper West and Savannah Regions of Ghana and to examine the connectedness of migrants. Using mixed methods, the study revealed that out-migration is high in our study areas, and the major reasons are to seek better job opportunities, to have access to higher education, for marriage (mostly women), and due to a lack of work at the origin. In addition, most migrants have lower formal educational levels before migrating, as there are no tertiary educational facilities in the study communities. Most migrants migrate to cities within Ghana where they have strong connections at their destinations. Since nine out of ten migrants live in Ghana, migration is largely internal and reflects national data (GSS 2023).

Social transformations in the study areas have been significant, particularly concerning economic, demographic, and technological factors. While there have been improvements in technology and an increase in population and urbanisation (demography), there has been a decline in income, per capita farmland, and access to capital over the past decade for most households. The economic woes of many are exacerbated by declining household economic assets such as livestock and poor yield, partly caused by changing climatic conditions in Northern Ghana (Aketemah 2018). Our study shows that local conditions shaped by global forces, such as COVID-19, have influenced the supply of fertilisers to rural farmers in Ghana, which has increased the cost of production, contributing to migration.

Political and cultural factors have remained relatively the same as perceived by the respondents. Consequently, the dimensions of social transformation that have changed (economic, technological, and demographic) contributed to out-migration in our study areas. While the economic, technological, and demographic factors cause out-migration, migration has limited influence on social transformation. Aside from the change in education level facilitated by migration due to the lack of tertiary institutions in the study areas, migration has not caused significant change. Through migration, many people are becoming transformative and innovative and substituting some traditional farming practices with mechanised agricultural practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.S. and J.K.T.; methodology, J.K.T., E.A. and E.Y.; software, E.G.A.N.; validation, E.G.A.N., E.A., C.O.-A., E.Y., M.B.S. and J.K.T.; formal analysis, M.B.S., E.A. and E.G.A.N.; resources, all authors.; data curation, E.Y. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors took turns; visualization, E.Y.; supervision, M.B.S.; project administration, M.B.S.; funding acquisition, J.K.T., C.O.-A. and M.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union (FED/2019/397-558) under the REACH-STR project. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and under no circumstances can be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies (protocol code UDS/RB/045/19 and date of approval 10 January 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all research participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the research participants and authorities of the study communities for their time and for granting us permission to conduct the study. We also express our heartfelt gratitude to our field officers who assisted us in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aketemah, Augustina. 2018. Livestock Ownership and Poverty Reduction in Northern Ghana. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, Stephen. 2001. Studying social transformation. International Political Science Review 22: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, Stephen. 2010. Understanding global migration: A social transformation perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36: 1565–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, Hein, and Sonja Fransen. 2018. Social Transformation and Migration: An Empirical Inquiry. IMI Working Paper Series 141; Amsterdam: International Migration Institute Network (IMIn). [Google Scholar]

- de Haas, Hein, Sonja Fransen, Katharina Natter, Kerilyn Schewel, and Simona Vezzoli. 2020. Social Transformation (International Migration Institute IMI Working Paper No. 166). Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Peter D., and Monica Minnegal. 2010. Theorizing social change. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16: 629–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, Jon. 1983. Explaining Technical Change: A Case Study in the Philosophy of Science. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Etwire, Prince Maxwell, Saaka Buah, Mathieu Ouédraogo, Robert Zougmoré, Samuel Tetteh Partey, Edward Martey, Sidzabda Djibril Dayamba, and Jules Bayala. 2017. An assessment of mobile phone-based dissemination of weather and market information in the Upper West Region of Ghana. Agriculture & Food Security 6: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faist, Thomas, Mustafa Aksakal, and Kerstin Schmidt. 2018. Migration and social transformation. In The Routledge International Handbook of European Social Transformations. Edited by Peeter Vihalemm, Anu Masso and Signe Opermann. London: Routledge, pp. 283–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fazey, Ioan, Peter Moug, Simon Allen, Kate Beckmann, David Blackwood, Mike Bonaventura, Kathryn Burnett, Mike Danson, Ruth Falconer, and Alexandre S. Gagnon. 2018. Transformation in a changing climate: A research agenda. Climate and Development 10: 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSS. 2023. Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census: Thematic Report: Migration. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service. [Google Scholar]

- Held, David, Anthony McGrew, David Goldblatt, and Jonathan Perraton. 2000. Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. In Politics at the Edge: The PSA Yearbook 1999. Edited by Chris Pierson and Simon Tormey. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, Peggy. 1998. Social remittances: Migration driven local-level forms of cultural diffusion. International Migration Review 32: 926–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migration Data Portal. 2023. Migration Data in Western Africa. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/infographic/migration-western-africa (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Migration Data Portal. 2024. Total Number of International Migrants at Mid-Year 2020. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/international-data?i=stock_abs_&t=2020 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Osei-Amponsah, Charity, William Quarmine, and Andrew Okem. 2023. Understanding climate-induced migration in West Africa through the social transformation lens. Frontiers in Sociology 8: 1173395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanyi, K. 1994. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Policies. In Migration and Development: Perspectives from the South. Edited by Stephen Castles and Raul Delgado Wise. Geneva: IOM. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro. 2010. Migration and social change: Some conceptual reflections. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36: 1537–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, E. L. F., S. E. Eriksen, L. R. Fernandez Carril, B. C. Glavovic, and Z. Shawoo. 2021. Turbulent transformation: Abrupt societal disruption and climate resilient development. Climate and Development 13: 467–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbeh, Richard, and Prince Osei-Wusu Adjei. 2020. Social Networks and the Geographies of Young People’s Migration: Evidence from Independent Child Migration in Ghana. Journal of International Migration and Integration 21: 221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setrana, Mary Boatemaa, and Nauja Kleist. 2022. Gendered dynamics in West African migration. In Migration in West Africa: IMISCOE Regional Reader. Edited by Joseph K. Teye. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrink, Malte, and Hannah Niedenführ. 2020. Africa on the Move: Migration, Translocal Livelihoods and Rural Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Switzerland: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Teye, Joseph Kofi. 2022. Migration in West Africa: An introduction. In Migration in West Africa: IMISCOE Regional Reader. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Turolla, Maya, and Lisa Hoffmann. 2023. “The cake is in Accra”: A case study on internal migration in Ghana. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des études Africaines 57: 645–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDESA. 2020. International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination and Origin: United Nations. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- van Hear, Nicholas. 1998. New Diasporas: The Mass Exodus, Dispersal and Regrouping of Migrant Communities. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zaami, Mariama. 2020. Gendered strategies among northern migrants in Ghana: The role of social networks. Ghana Journal of Geography 12: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).