1. Introduction

1.1. Mental Health Challenges of COVID-19

The widespread outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 disrupted normal life globally in 2020 (

Ng et al. 2020). In efforts to slow the virus’s spread, governments implemented varying levels of social restrictions. In addition to the physical health complications caused by the pandemic, it also presented significant mental, emotional, and social challenges (

Baloran 2020;

Cao et al. 2020). Previous studies have shown that public health emergencies can have psychological effects on university students, inducing anxiety, fear, and worry, among other impacts (

Mei et al. 2011).

Brooks et al. (

2020) reported that the fear of infection, quarantine duration, frustration, boredom, and inadequate supplies and information were major stressors during quarantine. They concluded that the psychological impact of quarantine on the population is extensive, significant, and must be addressed not only during the pandemic, but also months or even years afterwards (

Brooks et al. 2020).

1.2. Vulnerable Adolescents

Furthermore, adolescents experienced uncertainty and sudden disruptions to their semester and activities, affecting their research projects, internships, and delayed graduations. A major theory related to COVID-19’s impact on young people is the concept of biographical disruption and loss of control (

Bury 1982). Biographical disruption refers to an impactful process caused by illnesses, basically negative, to self-conception and social interactions in the course of an individual’s life (

Pranka 2018).

Strauss (

2007) proposed that the process of biographical disruption began with “the turning point”, which provoked surprise, bitterness, confusion, tension and/or “a feeling of defeat in his or her experience of self”. Young people who were infected faced the risks of biographical disruption.

As adolescents may be asymptomatic carriers, they also worried about contracting the virus and transmitting it to others, potentially putting older family members at a higher risk of contracting this deadly disease (

Zhai and Du 2020). For students separated from friends and living through lockdowns, anxiety levels increased, as these psychological disorders are more likely to arise and worsen in the absence of interpersonal communication (

Cao et al. 2020;

Kmietowicz 2020;

Xiao 2020).

To summarize, the emotions of adolescents caused by contracting the disease, alongside illnesses of their family members, school closures, and staying at home orders, etc., were compounded with fear, worry, frustration, anxiety, anger, and shame.

1.3. COVID-19 Impact on Da Nang City, Vietnam

The COVID-19 pandemic in Da Nang went through several notable phases, starting in early 2020. In the initial phase, from January to March, the city recorded its first COVID-19 case. Immediately, Da Nang implemented preventive measures, including border controls and public health awareness campaigns. Residents were advised to practice personal hygiene to minimize the risk of virus transmission.

However, despite initial control efforts, Da Nang faced a significant challenge during the outbreak phase between July and August 2020. After a period of stability, the city unexpectedly experienced a second outbreak in July and a number of waves of infections, causing a rapid increase in cases. This led to the lockdown of certain areas, the suspension of non-essential services, and a request for residents to stay at home. The health sector swiftly implemented contact tracing and widespread testing to contain the virus’ spread. By September, thanks to decisive measures and public cooperation, Da Nang began to regain control of the situation. The city entered the control phase, which continued through the end of the year. The number of new infections steadily declined, and the city gradually lifted lockdown measures. Economic activities and businesses resumed, although social distancing and mask-wearing regulations remained in place to ensure safety.

In 2021, Da Nang launched an extensive COVID-19 vaccination campaign aimed at vaccinating as many residents as possible. This initiative played a crucial role in controlling the pandemic, and by late 2021, Da Nang entered the ‘new normal’ phase. While there were occasional isolated cases, the city managed the situation well and gradually reopened for tourism and economic activities. Although the city recovered, the long-term impacts of the pandemic remained a concern. Mental health issues, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), have become increasingly recognized, especially among students. These mental health challenges could develop months after the initial crisis (

Andrews et al. 2007). In a study by

Wei et al. (

2021), the importance of offering condolences to the families of those who died from COVID-19 was emphasized. Such expressions of sympathy not only honor the memory of the deceased, but also help alleviate feelings of guilt and sadness, offering healing effects for the survivors (

Wei et al. 2021).

Studies conducted in Brazil (

Gadagnoto et al. 2022), Italy (

Zaccagni et al. 2024), and several European countries (

Forte et al. 2021) showed the prevalence of negative emotions among adolescents during COVID-19. However, a large-scale study in Norway found that changes in adolescents’ psychosocial well-being during the pandemic were relatively small, with overall satisfaction in social relationships remaining stable (

Kozák et al. 2023). The contradictions of these studies can only be explained if there is a swing of moods across different social contexts and phases of the pandemic.

According to Bùi Thế Cường, since the onset of the pandemic, many studies have focused on comprehensive lessons aimed at improving the current state to better prepare for similar unavoidable crises in the future. Cường’s summary indicates that the international lessons learned began in healthcare and extended to politics, society, and the economy (

Cường 2024). However, lessons in crisis response that address the mental health of the community still seem to be an area needing enhancement.

1.4. Types of Positive and Negative Emotions

Emotions play a crucial role in students’ personality growth and social developments, directly impacting every aspect of their psychological health and academic life (

Moeller et al. 2020;

Phan et al. 2019). Positive emotions (e.g., enjoyment and enthusiasm) are associated with attention, concentration, engagement, and perseverance in learning activities, which are positively correlated with academic achievement (

Eccles 2005;

Moeller et al. 2020;

Schiefele 1996). Conversely, negative emotions (e.g., boredom, burnout, and anxiety) are known to reduce cognitive resources, thereby negatively affecting learning outcomes and academic performance (

Madigan and Curran 2020;

Moeller et al. 2020;

Schiefele 1996).

Pfefferbaum and North (

2020) indicate that negative emotions such as anxiety, fear, and loneliness were the main emotions experienced by university students in China during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Cao et al. (

2020),

Son et al. (

2020), and

Jia et al. (

2020) all confirmed that loneliness, fear, and anxiety were the most common negative emotions during COVID-19 among the same target groups.

Zhou et al. (

2020) found that, in addition to loneliness and fear, sadness was also prevalent among university students in China due to the pandemic.

1.5. Lessons on Emotional Recovery

In this context, our research interest is to investigate the factors and underlying agents behind the prevalent negative emotions experienced by adolescents in Da Nang City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected through school surveys in early 2023, and the following research questions were raised:

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, what types of negative emotions have students experienced? In particular, what are the most dominant negative emotions?

Did they also experience positive emotions during such difficult times? What were the most prevalent positive emotions?

In the post-COVID-19 era, is there a shift in emotions from negative to positive, indicating a rebound as part of recovery?

The research framework is shown in

Figure 1.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

There were 21 public schools in the city of Da Nang. Ten schools were conveniently selected as the authors have contact with teachers there. Nevertheless, the inclusion of schools was purposefully designed to cover all 7 districts of the city to reflect social diversities. Students in grades 10–12 voluntarily responded to the online survey distributed by teachers. However, authorization from the city education department, school management, and prior consent from parents or guardians was sought.

Data were collected online through a questionnaire on the Google Forms platform over the course of one month, from January 2023 to February 2023. The link to the online questionnaire was sent to teachers at the schools to invite students from grades 10 to 12 to participate on a voluntarily bases, with consent obtained from both them and their parents or guardians. Furthermore, approval from the Da Nang University on research ethics was obtained while the Vietnam Ministry of Education and Training, which approved and funded the implementation of this research.

2.2. Measurements

A questionnaire was designed to collect students’ emotional experiences in the following steps:

Emotional experiences, to be reported for the periods before and after the COVID-19 impact, included 5 positive emotions (joy, inspiration, positivity, tolerance, enthusiasm) and 6 negative emotions (loneliness, fear, anxiety, sadness, discomfort, annoyance/anger). Students were asked to indicate whether they experienced or did not experience these emotions. The questionnaire allowed participants to interpret the meaning of these terms subjectively, without predefined definitions or specific indicators. This approach aimed to capture their personal perceptions and lived experiences of these emotions.

For each emotion type, students were to indicate whether it was present or absent in both the before and after time periods.

Open-ended questions were employed to explore the reasons for experiencing the four major types of negative emotions, namely loneliness, anxiety, sadness, and fear. Answers to these questions were examined through content analysis.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the questionnaire, several validity tests were conducted, covering content validity, face validity, construct validity, criterion validity, and test–retest reliability. Each of these tests was essential to confirm that the questionnaire effectively measured the emotional experiences of students during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, the content validity of the questionnaire was established by referring to established emotion theories by

Ekman (

1992) and

Lazarus (

1991), which focus on basic emotions. According to these theories, emotions are universal, not just personal, and can be widely recognized in various contexts. The questionnaire included a range of positive and negative emotions such as joy, inspiration, positivity, tolerance, enthusiasm, loneliness, fear, anxiety, sadness, discomfort, and annoyance/anger. These emotions were carefully selected to represent the experiences students might face during the pandemic. Psychologists and educational experts reviewed the questionnaire and confirmed that it was appropriate for measuring these specific emotions.

In terms of face validity, the questionnaire was tested with a small group of students. The results indicated that the questions were clear and easily understood. Students provided feedback that the questions helped them identify and articulate their negative emotions effectively. This confirmed that the questionnaire had strong face validity, as it was able to meet the students’ needs in recognizing and expressing their emotional states. Regarding construct validity, the questionnaire not only asked students to identify their emotions, but also delved into the reasons behind those emotions. The responses were carefully analyzed and showed that the questions gathered detailed data, allowing for an accurate measurement of the emotional constructs targeted by the study. This helped ensure that the questionnaire measured what it was intended to measure. For criterion validity, the results from the questionnaire were compared to prior studies on students’ emotions during the pandemic. The comparison revealed a significant similarity between the findings, confirming that the questionnaire accurately reflected the emotional realities of students in the context of COVID-19.

Finally, to assess the test–retest reliability of the questionnaire, a group of students completed the same survey at two different time points before and after a certain period. The analysis of the results showed no significant changes in the emotions students experienced between the two surveys, indicating high stability in measuring these emotions. This demonstrated that the questionnaire could provide consistent and reliable data over time, making it a dependable tool for measuring students’ emotional responses in different contexts.

The results from all these validity tests confirm that the questionnaire meets all necessary criteria, including content, face, construct, and criterion validity, as well as test–retest reliability. These results validate the reliability of the questionnaire as an effective tool for collecting data on students’ emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Data Analysis

To examine the most prevalent emotions, both positive and negative, before and after COVID-19, simple descriptive statistics were used. T-tests were employed to examine whether significant differences existed in the sample of students between the pre- and post-crisis periods for both negative and positive emotions.

To explore the causes of the four major negative emotions, qualitative data were analyzed using the content analysis method developed by

Luo (

2023). The process is described as follows.

2.4. Questions Designed: Students Were Asked the Following Questions

In the context of COVID-19, what made you feel most scared?

In the context of COVID-19, what made you feel most worried?

In the context of COVID-19, what made you feel most lonely?

In the context of COVID-19, what made you feel most sad?

2.5. Data Preparation

To examine the reasons for the four major negative emotions, qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis, as developed by

Luo (

2023). The process was as follows:

Data Preparation:

The data from students’ stories and experiences were divided into meaningful units. Keywords or phrases describing the factors influencing why students felt fear, anxiety, loneliness, or sadness were recorded. Hundreds of manually filtered keywords and phrases were categorized and entered into an Excel file corresponding to each type of negative emotion.

Developing Initial Coding List:

Initial codes were developed based on major themes such as the impact of COVID-19, social distancing, family dynamics, online learning, and relationships with friends. New codes were added or expanded, such as: economic difficulties and food insecurity.

Developing Focused Coding (Core Codes):

Related sub-codes were grouped into larger categories (core codes) to highlight major themes and ensure consistency.

Re-Analysis of Data:

Qualitative data from the four questions were re-analyzed based on the established themes to identify the main causes behind the negative emotions.

2.6. Encryption Lists

According to the above processes, the following levels of encryptions are developed as shown in

Table 1.

The findings presented in

Table 1 reveal several key themes and factors that significantly influenced students’ emotional experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings emphasize the complex and multifaceted nature of the emotional challenges faced by adolescents, particularly in relation to feelings of loneliness, fear, anxiety, and sadness.

Loneliness emerged as a predominant emotion among students, driven by several factors such as lockdown measures, the lack of social interactions, and the disruptions to daily life.

Students expressed following routines. Many students reported feelings of isolation, as they were confined at home and unable to meet with friends or have regular face-to-face interactions with family members. These feelings of loneliness were further exacerbated by the fear of COVID-19 infection and its impact on their social relationships. As a result, several students experienced broken friendships and a lack of emotional support.

Fear was another prevalent emotion, primarily driven by concerns about contracting the virus, the possibility of losing loved ones, and the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic. The fear of death, isolation, and the mental health risks associated with prolonged quarantine were significant stressors. Additionally, students expressed anxiety about academic failure and economic hardship. The uncertainty about their academic performance, combined with concerns about their families’ financial stability, contributed to heightened levels of anxiety.

Anxiety was also linked to the ongoing uncertainty surrounding the pandemic and the disruption of academic routines. Many students expressed worry about their inability to meet academic goals, which was further amplified by the approaching exam dates and the overwhelming amount of material they had to learn. The difficulties of readjusting to school after the lockdown and the lack of social interaction also added to the anxiety students were experiencing.

In addition, economic challenges and food shortages were prominent concerns, as were irregular sleep patterns and changes in eating habits. These issues were closely tied to the stress and anxiety caused by the pandemic.

Sadness was another emotion that students struggled with during the pandemic, often connected to the emotional toll of social distancing and the inability to engage in social activities. Feelings of sadness were linked to the loss of social connections, the difficulties associated with adapting to online learning, and family conflicts. The broader social and economic consequences of the pandemic, such as the loss of loved ones, job instability, and a general sense of helplessness, also contributed to the pervasive sadness felt by many students.

5. Discussion

This survey of 640 students revealed that 35.9% identified lockdowns as a significant cause of loneliness, while 24.8% reported not feeling lonely. Feelings of isolation, helplessness, and strained family relationships contributed to their sense of loneliness. However, those who felt supported by family and friends regarded these connections as protective factors that enhanced their well-being. Health-related concerns were a dominant source of anxiety among students, with 47.66% fearing long-term effects of COVID-19. Only 3.28% of respondents reported fear of poor academic performance. This may be due to a lack of motivation to study on the part of students or the absence of teachers’ supervision. Further study is required to explore the real reasons and means to maintain high academic motivation in similar school abruption.

Among reasons for loneliness, lack of family support has the highest percentage, standing at 47.6%, and this was out of our expectations. During COVID-19, schools were closed and students were required to stay at home, and for most of the time, accompanied by parents. This shows that in the absence of good parent-and-child relationships, company does not prevent loneliness.

Students reported feelings of boredom and sadness stemming from unmet academic goals, disrupted routines, and negative behaviors such as overeating and excessive sleep. Academic setbacks, missed opportunities, and exposure to distressing media reports further exacerbated their emotional distress. Concerns for loved ones and frustration over others’ disregard for safety measures were common, while many expressed gratitude for the sacrifices made by frontline workers. The main fears included contracting the virus, dying, losing loved ones, and experiencing social isolation, along with concerns about academic decline. Additional worries included economic hardship, health issues, and struggles with loneliness and identity.

Many students continued to express anxiety about the prolonged pandemic, even in January 2023, during the second episode of the study. They voiced concerns about mortality and the possibility of loved ones contracting the virus. This suggests that the pandemic has left a lasting impact on young people’s mental health, even if it may not be immediately severe. Adverse experiences from this period could resurface when individuals encounter future life challenges.

Approximately 8.59% of students expressed concerns about declining academic performance due to the transition to online learning. Additionally, students reported worries about economic challenges, including food insecurity and feelings of loneliness and anxiety caused by restricted social interactions. Overall, these findings highlight the multifaceted nature of students’ concerns during the pandemic, encompassing health, academic, economic, and social dimensions.

However, to what extent do the situations reported in this study differ from the previously existing mental health conditions in Vietnam?

La et al. (

2020) conducted a study in Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Ming cities just one year prior to the pandemic in 2019. They reported that 16.9% of 757 students in grades 10–12 in three public schools, one in each city, had mental health difficulties, measured by the self-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire–SDQ (

Goodman 1997).

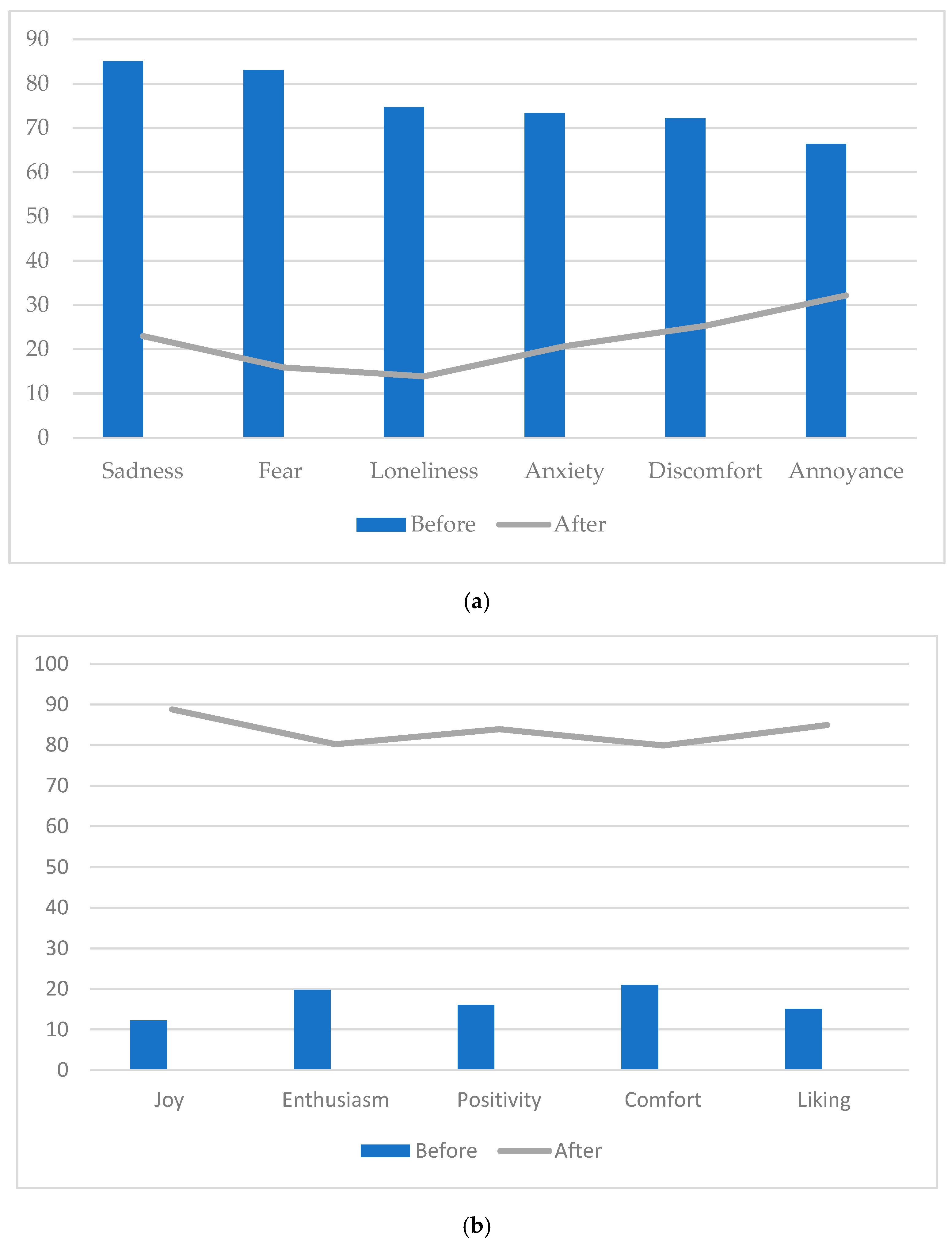

In

Table 2, it is evident that negative emotions reported by the participants for the First Episode ranged from 66.4% (annoyance/anger) to 88.7% (sadness), which are much higher than the 16.9% reported in the La, Dinh and Phan et al.’s study. In

Table 4, negative emotions reported for the second episode significantly dropped, but there were still 20.7% of students feeling loneliness, 23.0% anxiety, 25.3% discomfort, and 32.2% annoyance/anger.

Though the measurements of this study are different from La, Dinh and Phan et al.’s, it is clear that negative emotions are prominent compared to the experiences of a similar age group of Vietnam in 2019. The high rate of negative emotions during the second episode, reflected by the adolescents in this study, may even indicate a post-traumatic stress phenomenon.

Comparing the findings in quantitative and qualitative methods,

Table 4 shows that the most prevalent negative emotions are sadness (85.1%), fear (83.1), loneliness (74.7%), and anxiety (73.4%). This justifies the selection of qualitative questions in this study, as the same four negative emotions were chosen for open-ended questions. With hindsight, the other two negative emotions should have been included because in the second episode they became the most prevalent with discomfort (25.3%) and annoyance/anger (32.2%). Limited by the research design, there is no explanation to show why these two negative emotions linger on while the other four have all declined. Seemingly, discomfort, annoyance, and anger have prolonged effects.

7. Limitations and Contributions

This study has many limitations. After the outbreak of COVID-19, adolescent mental health has become a major concern for education authorities. This explains why mental health conditions statistics for young people before 2020 is not readily available. On the other hand, this study employs a recollection approach in collecting data from the first episode. People may consider that these data from memories may not be accurate.

As the reported rate of negative emotions is so high, (

Table 2), the chances of over-exaggeration will be minimal.

This study contributes to the understanding of emotions during COVID-19, which will change over time. It demonstrates that young people who were occupied by negative emotions in the beginning are capable of bouncing back. It shows that human natural healing will take place after a traumatic event.

Some students reported positive emotions even during the pandemic. Delineating the factors contributing to this resilience deserves further scientific study. Concerns are also raised about the impact on students with prior psychological weaknesses. This is another research priority which can only be addressed with proper approval and consent.

Most students have successfully bounced back after the COVID-19. Unfortunately, factors leading to this recovery are not measured in this study. Again, this could be a valuable area for future research.

8. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised significant concerns about the mental health of an entire generation, particularly among children, adolescents, and their parents. However, the pandemic may merely highlight the tip of the iceberg regarding mental health—a longstanding issue that has often been overlooked. Under the strain of the disease and its aftermath, risks and damages to mental well-being have become increasingly complex.

During the pandemic’s peak, students experienced prominent emotional challenges, including sadness, loneliness, fear, and anxiety. These emotions stemmed from fears of illness, death, isolation, and losing social connections. Additionally, setbacks in achieving educational goals left adolescents feeling increasingly isolated and apprehensive. Even though the pandemic has subsided, its impact remains deeply ingrained in students’ memories, forming a haunting and unsettling chapter that is difficult to forget. The vivid recollections of these experiences demonstrate the profound psychological toll of isolation, emphasizing the need for addressing its consequences not only during crises, but for months or even years afterwards (

Brooks et al. 2020).

Looking ahead, while the pandemic may have passed, humanity will likely face future health crises or other emergencies. This reality means that children’s lives may not always remain peaceful. Therefore, conducting systematic research to comprehensively assess children’s and adolescents’ mental health is a scientifically essential endeavor. Such research should aim to develop early and sustainable intervention strategies that address both immediate and long-term challenges. This necessity calls for the establishment of more comprehensive and holistic approaches within the field of social work. These strategies should focus on intervention at multiple levels—from early prevention and mitigation to in-depth therapeutic responses. Effective interventions must also empower individuals by promoting the principles of healthy behavior. To achieve genuine well-being, individuals must not only receive support, but also actively engage in addressing their mental health challenges, benefiting both themselves and their communities.