Navigating the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 in Community Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 Learning Loss

2.2. Community Schools

3. Theoretical Frameworks

4. The Current Study

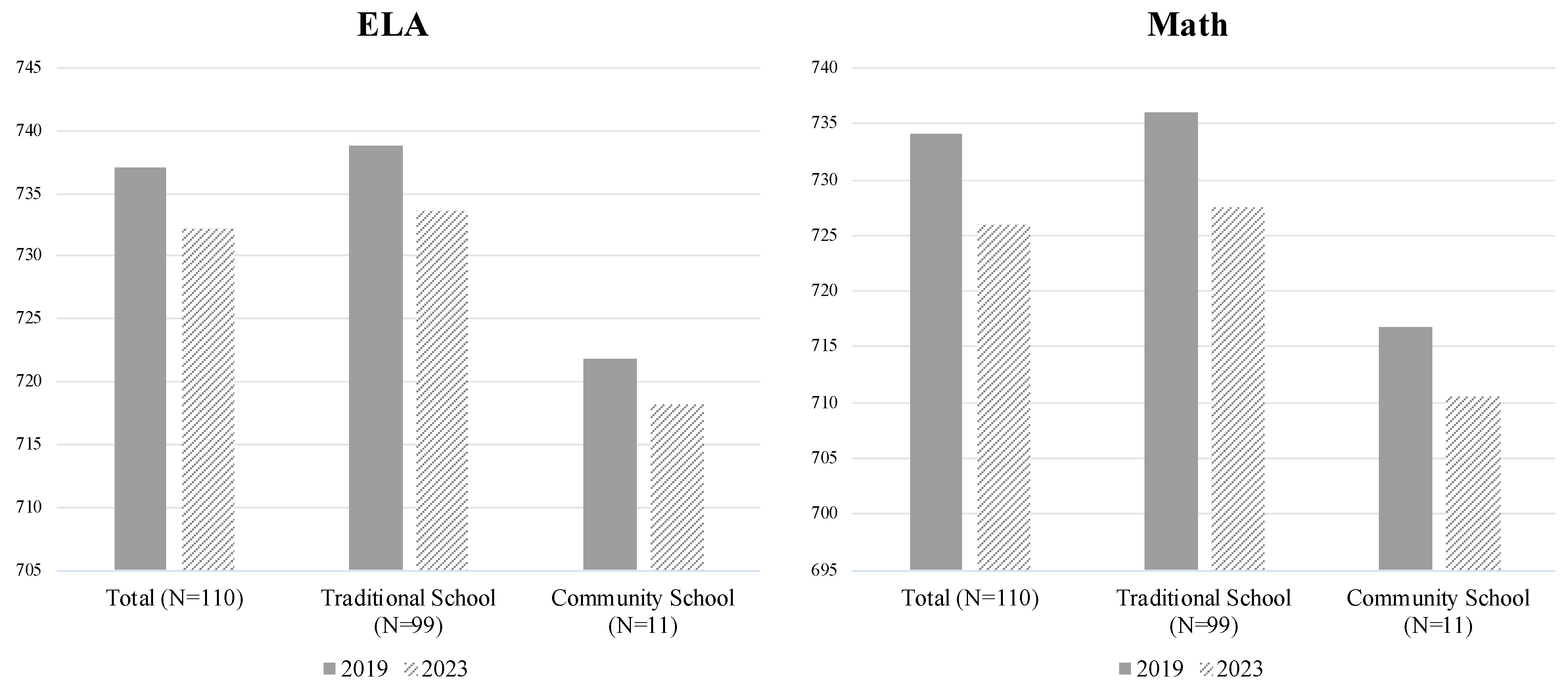

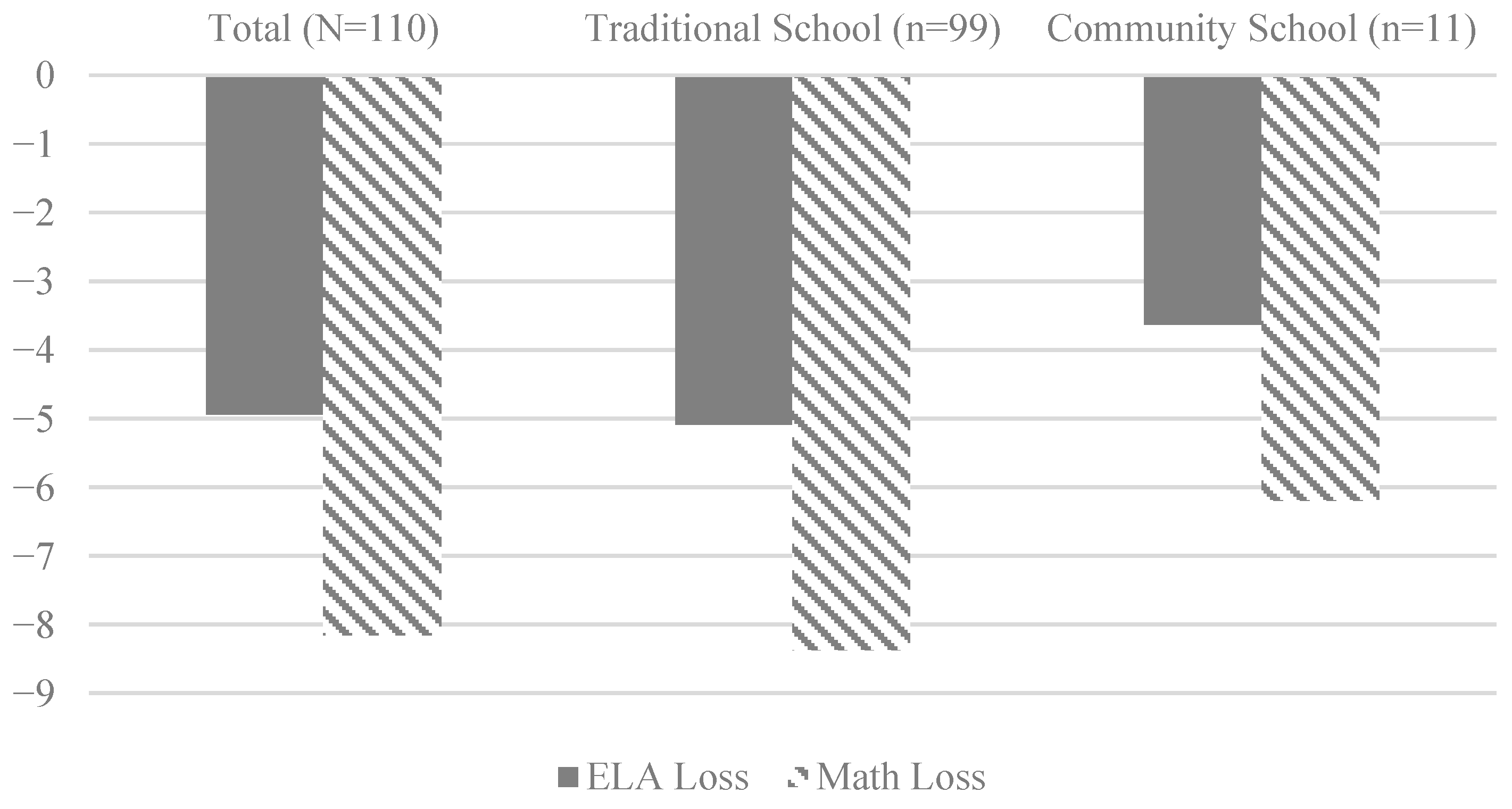

- To what extent did schools experience changes in state-standardized test scores between 2019 and 2023?

- To what extent did changes in state-standardized test scores differ descriptively between community schools and traditional schools?

- How did community schools experience and navigate the COVID-19 pandemic?

5. Methods

5.1. Data

5.2. Missing Data

5.3. Measures

5.4. Analytical Approach

5.4.1. Descriptive Quantitative Analysis

5.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Demographics

6.2. State-Standardized Assessment Scores

6.3. Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis

6.3.1. COVID-19 Challenges

Principal Michelle communicates two key dynamics that characterize the community her school serves. First, the school supported families who needed access to basic resources fundamental to healthy family functioning and child development even before the pandemic. Second, Principal Michelle describes how the poor and historically minoritized communities her school serves suffered disproportionately during the pandemic.We’ve always had to support parents. I always tell people … the “hill” like catches a cold, the “hood” gets pneumonia… If you got COVID issues there then…it’s going to be more concentrated here… So we’re already used to, like, supporting families with housing or food. You’re trying to find them a doctor or like, like, those are things that we’ve always had to do.(Principal Michelle)

Many families served by the community schools had no choice but to face the uncertainty of working through the pandemic; potentially expose themselves and their families to COVID-19; and support their children at home. These challenges undoubtedly affected family-school relationships and student learning in the community schools we studied.For families who work hourly wages who get COVID, who are out of work for 14 days; those 14 days are a detriment that they can never recover from. Right, because I’ve lost 14 days of pay when I’m already paycheck to paycheck.(Principal Stacy)

These casual and informal interactions helped build relationships and trust between Laura and the families. Laura continued to describe how COVID-19 school closures affected the relationships of CSMs, teachers, and families:So it is like, “I’m so used to just being able to go to Miss [Laura]’s classroom and say I need deodorant,” or a parent coming to my school and saying “Hey, we don’t really have any groceries. I don’t get my food stamps until the 15th. Do you have any grocery gift cards?” They could just walk to the school.(Laura, CSM)

Not only did the community schools serve as a hub to distribute resources for families, but the schools also served as a hub to develop relationships with families and school staff. Especially early on in the pandemic, the lack of in-person contact became a large hurdle to connecting with and supporting families.But now, they can’t, you know, I can’t be in contact with them, I can’t touch them, I can’t hug them. So that has been a difficult part, just that connection piece… How do we navigate this relationship when this is not what we’re used to?(Laura, CSM)

The community schools experienced challenges with communications before COVID-19, such as families changing phones or moving houses throughout the year. However, the pandemic exacerbated these challenges to a degree that made it nearly impossible to contact some families without the physical connection to schools.So COVID put our parents in a really bad situation where technology wasn’t always accessible, and that was the only way that we communicate with them. So if their technology wasn’t up to date, if their cell phone wasn’t turned on, then now it’s no way to get in contact with them. If they’re going from house to house and we don’t have an accurate address, it is hard for us to get paperwork to them.(Laura, CSM)

6.3.2. Importance of CSMs

The CSMs at the community schools were able to support students and families with accessing basic needs and—perhaps more importantly—coordinate the allocation of these resources.Just being able to, like, meet basic needs, I think it’s a huge thing because most [traditional] schools don’t have someone who has the time to like really coordinate that kind of stuff. I think in COVID, in particular, people were coordinating deliveries to homes, so that was really huge.(Cathy, District Staff)

These comments suggest that the families at community schools were more likely to receive donations and the donations they need most because of the role CSMs play within their schools. Again, receiving these resources was particularly critical for the community schools in our study as they served students and families from historically underinvested communities—those overwhelmingly impacted by the pandemic. While the families served by the community schools still faced many challenges during this time, the community schools were able to remain constant in the support they provided them.When I work with the [community schools], like, at least they have these people there whose job it is to, like, do the stuff I do, okay. So it’s easier to work with them, than with everyone else…They could do a good job at distributing [donations] to people who need it most.(Terry, District Coordinator of Business Partners)

Before school closures, CSMs developed authentic relationships with families by providing the support they needed. As a result of having pre-existing relationships, CSMs were comfortable and prepared to support families during the COVID-19 school closures. Despite the compounding challenges that the pandemic created for the schools in this study, the community schools were well-positioned to help families and students navigate these obstacles.A lot of our parents struggle, a lot of our parents have been impacted by the pandemic, so a lot of them, they call and have a need…There’s a community [who] knows [them] by name and able to call and get support, as opposed to trying to figure out who’s going to support this family right this moment.(Principal Smith)

6.3.3. COVID Response

Having the CSM not only helped coordinate longer-term resources and services, but also allowed for quick responses to immediate needs.[I am] just able to meet needs in a more immediate way. We have a family who needs food, okay, I got a, I got a gift card, boom. We have family who needs a Lyft ride because they got to get their kids to children’s hospital all the way across town, and they’re deaf and hard of hearing and so taking a bus is really, really hard. Okay, let me get this partner who I know does Lyft gift cards.(Jasmine, CSM)

Teachers could directly address challenges that their students faced in the virtual classroom using the community school strategy. The entire school community relied on the resources provided by the community school strategy to directly and quickly address challenges that impacted students’ academic experiences and beyond.All of our parents and our students are going through so much, and they [the teachers] leaned on me so much this year. Like, you know, “my parents needed internet”, “my parents need a laptop”, “my parents need a computer”, “my parents they just got evicted”, “I got parents that’s not eaten”… So we just, like, [Ms. Laura] “I need this I need this I need that”.(Laura, CSM)

Amy went on to describe how addressing food security was a pressing issue during and following school closures. As the district-level staff, she was able to identify the types of food (e.g., prepared meals, shelf-stable food) that schools needed and develop broader, citywide relationships. Families and students served by the community schools benefited not only from the school-level resources but also from the district-level network of partnerships.There were certain like trends of needs that were coming up across all of our schools and [we] needed someone to kind of zoom out and build relationships and a network of partners that can support on that across all of our schools.(Amy, District Staff)

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

| CSM | Community School Manager |

| ELA | English Language Arts |

References

- Alaimo, Katherine, Christine M. Olson, and Edward A. Frongillo, Jr. 2001. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children’s cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics 108: 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, Martin J., Atelia Melaville, and Bela P. Shah. 2003. Making the Difference: Research and Practice in Community Schools; Washington, DC: The Coalition for Community Schools. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED477535.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Camera, Lauren. 2021. Community Schools’ See Revival in Time of Heightened Need. U.S. News and World Report. August 25. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2021-08-25/community-schools-see-revival-in-time-of-heightened-need (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Di Pietro, Giorgio. 2023. The impact of COVID-19 on student achievement: Evidence from a recent meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 39: 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, Robin, and Harry Anthony Patrinos. 2022. Learning loss during COVID-19: An early systematic review. Prospects 51: 601–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryfoos, Joy. 2002. Partnering full-service community schools: Creating new institutions. Phi Delta Kappan 83: 393–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryfoos, Joy, and Sue Maguire. 2002. Inside Full-Service Community Schools. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durham, Rachel E., and Faith Connolly. 2016. Baltimore Community Schools: Promise & Progress; Baltimore: Baltimore Education Research Consortium. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED567805.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Durham, Rachel E., Jessica Shiller, and Faith Connolly. 2019. Student attendance: A persistent challenge and leading indicator for Baltimore’s community school strategy. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 24: 218–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Week. 2020. School Districts’ Reopening Plans: A Snapshot [Dataset]. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/school-districts-reopening-plans-a-snapshot/2020/07 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engzell, Per, Arun Frey, and Mark D. Verhagen. 2021. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118: e2022376118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Joyce L. 1987. Towards a theory of family-school connections. In Social Intervention: Potential and Constraints. Edited by K. Hurrelmann Klaus Hurrelmann, Franz-Xaver Kaufmann and Friedrich Lösel. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 121–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Leah K., Tara W. Strine, Leigh E. Szucs, Tamara N. Crawford, Sharyn E. Parks, Danielle T. Barradas, Rashid Njai, and Jean Y. Ko. 2020. Racial and ethnic differences in parental attitudes and concerns about school reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States. MMWR-Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69: 1848–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooms, Ain A., and Joshua Childs. 2021. “We Need to Do Better by Kids”: Changing Routines in U.S. Schools in Response to COVID-19 School Closures. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 26: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerstein, Svenja, Christoph König, Thomas Dreisörner, and Andreas Frey. 2021. Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement—A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 746289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmey, Sinéad, and Gemma Moss. 2023. Learning disruption or learning loss: Using evidence from unplanned closures to inform returning to school after COVID-19. Educational Review 75: 637–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, Megumi G., Steven B. Sheldon, and Yolanda Abel. 2023. “Getting things done” in community schools: The institutional work of community school managers. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 35: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, Veronique, Josue De La Rosa, Ke Wang, Sarah Hein, Jijun Zhang, Riley Burr, Ashley Roberts, Amy Barmer, Farrah Bullock Mann, Rita Dilig, and et al. 2022. Report on the Condition of Education 2022; Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics at IES, No. NCES 2022-144.

- Jack, Rebecca, and Emily Oster. 2023. COVID-19, school closures, and outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives 37: 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, William R., John Engberg, Isaac M. Opper, Lisa Sontag-Padilla, and Lea Xenakis. 2020. Illustrating the Promise of Community Schools. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Jyoti, Diana F., Edward A. Frongillo, and Sonya J. Jones. 2005. Food insecurity affects school children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. The Journal of Nutrition 135: 2831–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimner, Hayin. 2020. Community Schools: A COVID-19 Recovery Strategy. Stanford: Policy Analysis for California Education. [Google Scholar]

- Klevan, Sarah, Julia Daniel, Kendra Fehrer, and Anna Maier. 2023. Creating the Conditions for Children to Learn: Oakland’s Districtwide Community Schools Initiative. Washington, DC: Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhfeld, Megan, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, and Karyn Lewis. 2020a. Learning During COVID-19: Initial Findings on Students’ Reading and Math Achievement and Growth. Portland: NWEA. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, Megan, James Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, and Jing Liu. 2020b. Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Educational Researcher 49: 549–65. [Google Scholar]

- Learning Heroes and TNTP. 2023. Investigating the Relationship Between Pre-Pandemic Family Engagement and Student and School Outcomes. Available online: https://bealearninghero.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/FACE-Impact-Study.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Leech, Nancy L, Sophie Gullett, Miriam Howland Cummings, and Carolyn A. Haug. 2022. The challenges of remote K-12 education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences by grade level. Online Learning 26: 245–67. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Anna, Julia Daniel, Jeannie Oakes, and Livia Lam. 2017. Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence. Palo Alto: Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Anna, Julia Daniel, Jeannie Oakes, and Livia Lam. 2018. Community schools: A promising foundation for progress. American Educator 42: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, David T., and Martha Bradley-Dorsey. 2022. Reopening schools in the United States. In COVID-19 and the Classroom: How Schools Navigated the Great Disruption. Edited by David T. Marshall. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Maryland State Department of Education. 2021. Blueprint for Maryland’s Future: Community Schools + Concentration of Poverty Grants. Blueprint for Maryland’s Future. Available online: https://blueprint.marylandpublicschools.org/community-schools/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Merriam, Sharan B. 2009. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, Alasdair, Danilo Buonsenso, Sebastián González-Dambrauskas, Robert C. Hughes, Sunil S. Bhopal, Pablo Vásquez-Hoyos, Muge Cevik, Maria Lucia Mesa Rubio, and Damian Roland. 2023. In-person schooling is essential even during periods of high transmission of COVID-19. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 28: 175–79. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Reopening K-12 Schools During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Prioritizing Health, Equity, and Communities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2023. School Pulse Panel: Surveying High-Priority, Education-Related Topic; Washington, DC: Interactive Results. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/spp/results.asp (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Oakes, Jeannie, Anna Maier, and Julia Daniel. 2017. Community Schools: An Evidence-Based Strategy for Equitable School Improvement; Boulder: National Education Policy Center. Available online: https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/equitable-community-schools (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Obradović, Jelena, Jeffrey D. Long, J. J. Cutuli, Chi-Keung Chan, Elizabeth Hinz, David Heistad, and Ann S. Masten. 2009. Academic achievement of homeless and highly mobile children in an urban school district: Longitudinal evidence on risk, growth, and resilience. Development and Psychopathology 21: 493–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Caner, Claudia Reiter, Dilek Yildiz, and Anne Goujon. 2022. Projections of adult skills and the effect of COVID-19. PLoS ONE 17: e0277113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, Khalida, Phuc Quang Bao Tran, Abdulelah A. Alghamdi, Ehsan Namaziandost, Sarfraz Aslam, and Tian Xiaowei. 2022. Identifying the Leadership Challenges of K-12 Public Schools During COVID-19 disruption: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 875646. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1999. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research 34: 1189–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Provinzano, Kathleen Teresa, Ryan Riley, Bruce Levine, and Allen Grant. 2018. Community schools and the role of university-school-community collaboration. Metropolitan Universities 29: 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Jane, and Martin J. Blank. 2020. Twenty years, ten lessons: Community schools as an equitable school improvement strategy. Voices in Urban Education 49: 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, Yvonne, Marybeth Shinn, and Beth C. Weitzman. 2004. Academic achievement among formerly homeless adolescents and their continuously housed peers. Journal of School Psychology 42: 179–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, David H., Candace J. Erickson, Mutya San Agustin, Sean D. Cleary, Janet K. Allen, and Patricia Cohen. 1996. Cognitive and academic functioning of homeless children compared with housed children. Pediatrics 97: 289–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Mavis G., Claudia Galindo, and Dante DeTablan. 2019. Leadership for collaboration: Exploring how community school coordinators advance the goals of full-service community schools. Children & Schools 41: 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, Steven B. 2003. Linking school-family-community partnerships in urban elementary schools to student achievement on state tests. Urban Review 35: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Steven B. 2007. Improving student attendance with school, family, and community partnerships. Journal of Educational Research 100: 267–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Steven B., and Joyce L. Epstein. 2002. Improving student behavior and school discipline with family and community involvement. Education & Urban Society 35: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, Erin, Dana Thomson, Francesca Longo, and Eric Dearing. 2019. Student learning and development in economically disadvantaged family and neighborhood contexts. In The Wiley Handbook of Family, School, and Community Relationships in Education. Edited by Steven B. Sheldon and Tammy A. Turner-Vorbeck. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 399–417. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Patricia, Zach Timpe, Jorge Verlenden, Catherine N. Rasberry, Shamia Moore, Marshalyn Yeargin-Allsopp, Angelika H. Claussen, Sarah Lee, Colleen Murray, Tasneem Tripathi, and et al. 2023. Challenges experienced by U.S. K-12 public schools in serving students with special education needs or underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic and strategies for improved accessibility. Disability and Health Journal 16: 101428. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, Charles, and Abbas Tashakkori. 2006. A general typology of research designs featuring mixed methods. Research in the Schools 13: 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2020. Policy Brief: Education During COVID-19 and Beyond. UN Policy Briefs. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- U.S. Department of Education. 2024. Full-Service Community Schools Program (FSCS); Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-birth-grade-12/school-community-improvement/full-service-community-schools-program-fscs (accessed on 21 November 2024).

| Stakeholder Role | Data Collection Format | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connected School Managers | Interview | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Principals | Interview | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Central District Staff | Interview | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Community Partner | Interview | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Teachers | Focus Group | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Families | Focus Group | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Family or Community Engagement School Teams | Focus Group | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 15 | 17 | 15 |

| Total (N = 110) | Traditional School (n = 99) | Community School (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School Level n (%) | |||

| Elementary | 70 (63.6%) | 68 (68.7%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Middle (grades 6–8) | 13 (11.8%) | 7 (7.1%) | 6 (54.5%) |

| High (grades 9–12) | 17 (15.5%) | 15 (15.2%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| K-8 | 8 (7.3%) | 8 (8.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Middle-High | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Student Demographics | |||

| Gender 1 | |||

| Female | 48.6% | 48.7% | 47.7% |

| Male | 51.3% | 51.2% | 52.3% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 66.8% | 64.3% | 89.5% |

| White | 26.2% | 28.3% | 7.1% |

| Hispanic | 18.5% | 19.5% | 9.5% |

| Other non-white race 2 | 7.0% | 7.4% | 3.4% |

| Special Education Status | 17.3% | 16.8% | 21.7% |

| ELL Status | 14.7% | 15.6% | 7.0% |

| At-Risk Status | 57.3% | 54.8% | 80.4% |

| Economically Disadvantaged | 8.4% | 8.1% | 10.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hine, M.G.; Sheldon, S.B.; Abel, Y. Navigating the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 in Community Schools. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040223

Hine MG, Sheldon SB, Abel Y. Navigating the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 in Community Schools. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(4):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040223

Chicago/Turabian StyleHine, Megumi G., Steven B. Sheldon, and Yolanda Abel. 2025. "Navigating the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 in Community Schools" Social Sciences 14, no. 4: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040223

APA StyleHine, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., & Abel, Y. (2025). Navigating the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 in Community Schools. Social Sciences, 14(4), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040223