Abstract

Coming out has been found to be associated with favorable long-term social and psychological outcomes among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people. It is therefore important to understand the system of social and psychological factors that predict degree of outness in this population. The integrative theoretical model proposed in this article postulates that social factors (e.g., exposure to minority stressors, access to social support) trigger changes in sexual identity, which in turn determine one’s degree of outness. The model is tested in two cross-sectional survey studies (Study 1 [N = 295]) and Study 2 [N = 156]) of LGB people in the United Kingdom. Discrimination and general social support were directly and positively associated with outness and indirectly through the mediation of sexual identity processes. LGB social support was indirectly associated with outness through sexual identity processes. Interventions should focus on facilitating access to varied social support and on preventing or alleviating sexual identity threat in the face of minority stressors.

1. Introduction

Coming out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB)1 can be a psychologically challenging process given the risks associated with the disclosure of a potentially stigmatized identity element (Solomon et al. 2015). Coming out is rarely a singular event but rather can occur several times across the life course as one moves from one social context to another (Akers et al. 2021). LGB people vary in terms of the extent to which they are out to others (i.e., their degree of outness). For instance, they may come out to some people but not to others, and they may tailor the amount of information about their sexuality that they divulge to particular individuals (Mohr and Fassinger 2000).

On the whole, coming out has been found to be associated with favorable long-term outcomes for identity development, psychological wellbeing, and social relationships (Ballester et al. 2021; Bejakovich and Flett 2018; Cass 1979; Jaspal and Breakwell 2022; Lopes and Jaspal 2024). It is noteworthy, however, that studies have also examined some of the negative aspects of coming out, such as negative affect, low self-worth and depression (Legate et al. 2012), the experience of identity threat (Breakwell and Jaspal 2022; Lopes and Jaspal 2024), and the elevated risk of suicidality (Feinstein et al. 2023) that can arise when disclosing one’s sexual identity to others.

It is important to support LGB people to come out in ways that promote psychological wellbeing, and to do so, it is essential to understand the social and psychological determinants of coming out decision-making. Drawing upon elements of identity process theory (Breakwell 2015; Jaspal and Breakwell 2014) and minority stress theory (Meyer 2003), the present studies test a theoretical model of social triggers (i.e., minority stressors and forms of social support), intrapsychic sexual identity processes (e.g., sexual identity salience, threat, and uncertainty), and the degree of outness in LGB people. The integrative model proposes that social factors may bring about changes in identity that in turn shape behaviors, such as coming out.

1.1. Minority Stressors and Outness

Positive correlations between the distal minority stressor of discrimination and level of outness have been found. It is often reasoned that, although coming out is generally beneficial, being more open about one’s sexual identity also increases the risk of exposure to discrimination from people with unfavorable attitudes toward LGB people (Watson et al. 2022; White and Stephenson 2014). Conversely, individuals who conceal their sexual identity may be less likely to experience discrimination simply because people do not know that they are LGB. Passing is defined as “a performance in which one presents himself [or herself] as what one is not” and often involves feigning membership of a group that one does not really belong to (Rohy 1996, p. 219). Passing may constitute a strategy for limiting threats to the self, including discrimination (Breakwell 2015). Coming out can therefore be thought of as a double-edged sword—reactions may be positive or negative (Breakwell and Jaspal 2022).

Silveira et al. (2022) distinguish between distinct types of outness: functional outness, dysfunctional outness, functional concealment, and dysfunctional concealment. In general, functional outness and concealment are characterized by higher psychological wellbeing and dysfunctional outness and concealment by lower wellbeing. This suggests that there are distinct motivations underpinning levels of outness (and concealment)—functional outness and concealment may reflect a strategic approach to coming out, i.e., coming out to the right people and to an appropriate extent. Furthermore, identity process theory (Breakwell 2015; Jaspal and Breakwell 2014) posits that individuals deploy strategies for averting or minimizing threats to the principles of identity, that is, to their feelings of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness. It has previously been found that exposure to minority stressors can be threatening for identity because it undermines these principles (Lopes and Jaspal 2024).

Outness is a state that arises from the act of coming out—degree of outness increases as one comes out to more people and shares more information about one’s sexual identity with these people. Therefore, the positive relationship between discrimination and outness can also be viewed from a different perspective. It is possible that coming out operates as a sexual identity management strategy in the face of exposure to discrimination due to one’s sexual orientation. Indeed, Jaspal and Breakwell (2022) found that discrimination predicted greater outness. They reasoned that LGB people who face discrimination due to their sexual identity may elect to come out strategically, that is, to particular individuals and in ways that facilitate exposure to more favorable images of their sexual orientation (see also Orne 2011). It is therefore predicted that exposure to discrimination will be directly and positively associated with outness.

1.2. Social Support and Outness

Both general social support and social support from other LGB people have been found to be positively associated with degree of outness. On the one hand, more outness undoubtedly facilitates access to greater social support in relation to one’s sexuality since when others know of one’s sexuality, they can be supportive of it (Ratcliff et al. 2022). On the other hand, LGB people are more likely to come out when they believe that support is already accessible. In a similar vein, Reyes et al. (2023) found that perceived family support was a predictor of outness. Williams et al. (2016) found in their study of 133 gay and lesbian people that the belief that they would not be supported was associated with more subtle forms of support-seeking (e.g., appearing sad without self-disclosure, talking about issues unrelated to one’s sexuality purely to engage with others). This suggests that LGB people who do not have much social support may nonetheless attempt to seek support while concealing their sexuality. Morris et al. (2001) found that LGB community connectedness (a proxy for LGB social support) was the strongest predictor of outness in their structural equation model based on data from 2401 lesbian and bisexual women. This may reflect a sense of confidence brought about by one’s “chosen family” (i.e., other LGB people) in the face of possible rejection from one’s significant others (Milton and Knutson 2023).

Jaspal and Breakwell (2022) observed a positive association between social support and outness in their study of gay men and argued that the perception of support from others might empower them to employ potentially risk strategies, such as coming out. The main premise of their argument was that this is possible because one already has a social network of supporters to rely on if one is rejected. Furthermore, LGB people may develop predictions about how others will react to their coming out based upon their previous interactions with others. In short, LGB people who feel supported may believe that it is safe to come out to others. Indeed, Vale and Bisconti (2021) found that friend support operated as a protective factor against minority stressors, potentially enabling LGB people to be more out. Thus, it is predicted that both social support (Studies 1 and 2) and LGB social support (Study 2) will be directly and positively associated with degree of outness.

1.3. The Mediation of Intrapsychic Sexual Identity Processes

The present studies examine the potential mediation effects of intrapsychic sexual identity processes on the relationship between discrimination and social support and degree of outness. This hypothesis is based on the premise that both being exposed to discrimination (a distal minority stressor) and perceiving the availability of social support may precipitate particular ways of thinking about one’s identity, that is, its content and value dimensions (Breakwell 2015).

In their experimental study, Lopes and Jaspal (2024) found that LGB people who recalled a negative reaction to their coming out from somebody significant (a minority stressor) reported higher identity threat levels than those who recalled a “neutral” reaction, suggesting that exposure to minority stressors may generate changes in identity. Furthermore, in their longitudinal study, Walch et al. (2016) found that the relationship between discrimination and health outcomes was mediated by internalized homonegativity, also suggesting that exposure to a distal stressor precipitated identity change (i.e., viewing one’s sexual identity negatively). Similarly, Brandon-Friedman and Kim (2016) found that social support predicted various sexual identity processes, including internalized homonegativity, sexual identity salience, and sexual identity affirmation. More specifically, perceiving greater social support was associated with less internalized homonegativity but with greater sexual identity salience and affirmation. Sanscartier and MacDonald (2019) found that LGB community connectedness was associated with decreased levels of internalized heterosexism.

Sexual identity processes are in turn likely to affect LGB people’s decision-making regarding coming out. In their systematic and meta-analytic review of sexual identity centrality among sexual minorities, Hinton et al. (2022) found that sexual identity centrality was associated with higher levels of outness. Similarly, in a study of lesbian and bisexual women, bisexual women’s lower degree of outness compared to lesbian women was shown to be mediated by their lower sexual identity centrality (Dyar et al. 2015). Conversely, Xu et al. (2017) found internalized homonegativity to be negatively associated with degree of outness, suggesting that the negative evaluation of one’s sexual identity makes one less willing to disclose this identity element to others.

1.4. A Theoretical Model Predicting Degree of Outness

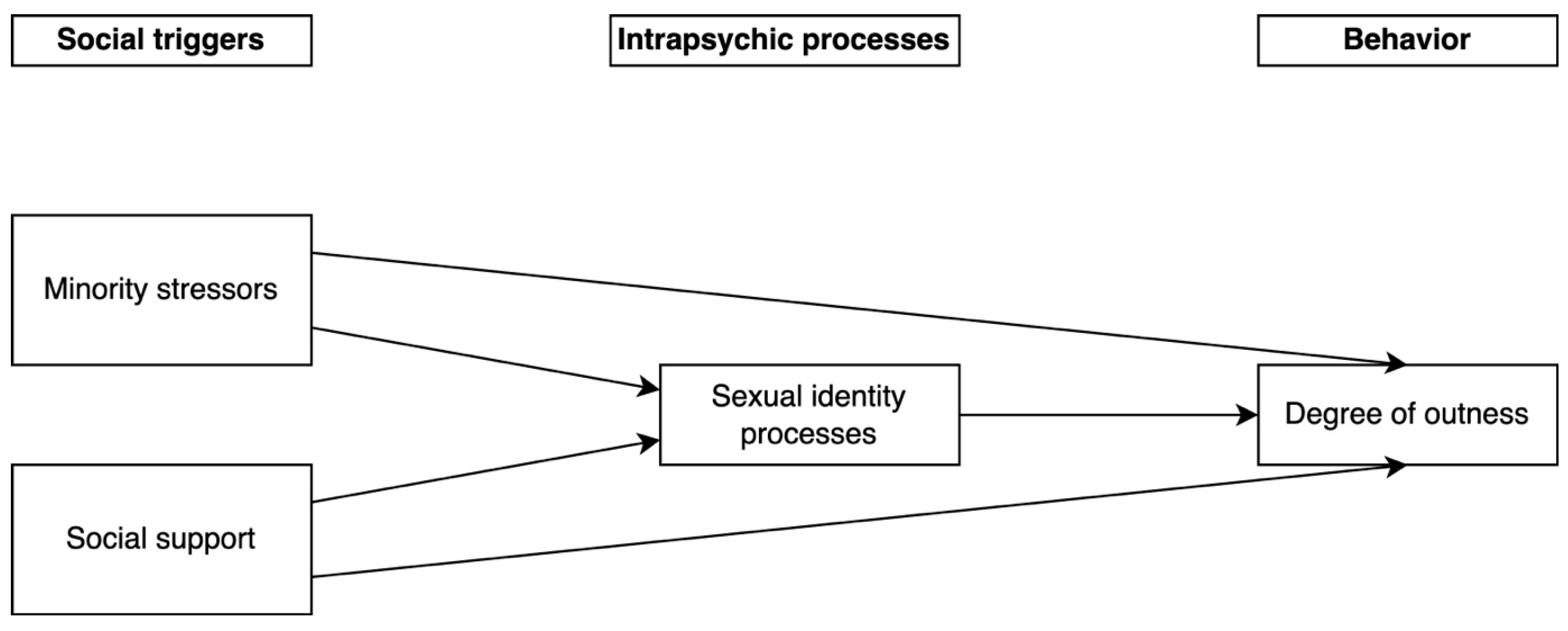

Figure 1 outlines a theoretical model predicting degree of outness among LGB people, which is based on existing evidence and tenets of identity process theory and minority stress theory. The model proposes that there are social triggers for intrapsychic sexual identity processes and for behaviors, such as coming out.

Figure 1.

A theoretical model predicting degree of outness in LGB people.

Minority stress theory (Meyer 2003) posits that LGB people’s health disparities can be attributed to exposure to stressors (e.g., discrimination) associated with their stigmatized sexual identity. In the present theoretical model, it is postulated that minority stressors can also influence cognitions (e.g., sexual identity processes) and behaviors (e.g., coming out) that in turn affect health and wellbeing outcomes. While minority stress theory generally views social support as a moderator of the relationship between exposure to minority stressors and health outcomes (Frost and Meyer 2023), in the present model, as a social trigger for outness, it is considered as a predictor.

Identity process theory (Breakwell 2015; Jaspal and Breakwell 2014) proposes that identity construction is underpinned by two processes: assimilation–accommodation (e.g., the hierarchical position that each identity element occupies in the identity structure—“being gay is important to me”) and evaluation (e.g., the meaning and value that one appends to this identity element—“I am uncertain about my sexual identity”). According to the theory, an individual strives to construct an identity that is characterized by feelings of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness. When these identity principles are undermined (for instance, by exposure to discrimination), identity is said to be threatened, and the individual will deploy varied strategies for coping. These strategies vary in their level of efficacy but can nevertheless be regarded as coping strategies insofar as their aim is to protect the self. Exposure to minority stressors, such as discrimination and a negative reaction to coming out, has been found to be associated with sexual identity threat (Breakwell and Jaspal 2022; Lopes and Jaspal 2024), which in turn is associated with the deployment of various coping strategies (Jaspal et al. 2022).

1.5. The Present Studies

This article presents the findings of two empirical studies using data from two different samples of LGB people to test the proposed theoretical model. The studies focus on different sexual identity processes and, where possible, use different scales for measuring the same construct. The rationale for reporting the findings of two studies conducted in this way was to enhance external validity since the relationships observed in the first study were expected to be replicated in the second study (Fabrigar et al. 2019).

In Study 1, the social triggers of discrimination and general social support and the intrapsychic sexual identity processes of sexual identity salience (the perception that one’s sexuality is an important element in the overall identity structure) and sexual identity uncertainty (uncertainty about the meaning and value of one’s sexuality as an identity element) are examined. In Study 2, the social triggers of discrimination (measured using a different scale), general social support and LGB social support, and the intrapsychic sexual identity processes of sexual identity threat (the perception that one’s sexuality undermines feelings of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness) and sexual identity stigma sensitivity (the internalized self-schema that others are disapproving of one’s sexuality) are examined.

2. Study 1

2.1. Hypotheses

- Discrimination should be directly and positively associated with degree of outness and indirectly associated through sexual identity salience. More specifically, since exposure to discrimination due to a particular identity element should render this element more salient than usual, as observed in many social group contexts (e.g., Hughes and Hurtado 2018; Hurtado et al. 2015; Thompson 1999), discrimination should be positively associated with sexual identity salience. Sexual identity salience should in turn be positively associated with degree of outness.

- General social support should be directly and positively associated with degree of outness and indirectly associated through both sexual identity salience and sexual identity uncertainty. More specifically, because general social support can facilitate feelings of authenticity in relation to identity (Alchin et al. 2024), it should be positively associated with sexual identity salience which in turn should be positively associated with degree of outness. In a similar vein, social support should be negatively associated with sexual identity uncertainty which in turn should be negatively associated with degree of outness.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Design, Participants, and Procedure

A total of 295 LGB individuals were recruited using a convenience sampling approach on Prolific, an online participant recruitment platform, to participate in a cross-sectional correlational survey study in 2022. The only inclusion criteria were self-identification as LGB or with another non-heterosexual identity label and being aged 18 or over. There were no missing data, and therefore, all 295 cases were retained for analysis.

Participants indicated their age, gender, and sexual orientation and then completed measures of discrimination, general social support, sexual identity salience, sexual identity uncertainty, and degree of outness. There were 141 (47.8%) self-identified men, 153 (51.9%) self-identified women, and 1 (0.3%) person who described their gender as “other”. A total of 54 (18.3%) individuals self-identified as gay, 38 (12.9%) as lesbian, 202 (68.5%) as bisexual, and 1 (0.3%) as “other”. The participant who reported their sexual identity as “other” did not define their sexual identity in the free text field.

2.2.2. Measures

The 9-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al. 1997) was used to measure perceived discrimination due to one’s sexual orientation on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = never to 6 = almost every day). The scale included items such as “You are treated with less courtesy than other people are”. A higher mean score indicated more frequent discrimination due to one’s sexual orientation (α = 0.92).

The 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (Shortened) (Cohen et al. 1985) was used to measure general social support on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = definitely false to 4 = definitely true). The scale included items such as “I feel that there is no one I can share my most private worries and fears with”. A higher mean score indicated higher general social support (α = 0.88).

The 5-item Identity Centrality subscale of the Lesbian Gay and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS) (Mohr and Kendra 2011) was used to measure sexual identity salience on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The subscale included items such as “I believe being LGB is an important part of me”. A higher mean score indicated higher sexual identity salience (α = 0.88).

The 4-item Identity Uncertainty subscale of the LGBIS (Mohr and Kendra 2011) was used to measure sexual identity uncertainty on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The subscale included items such as “I’m not totally sure what my sexual orientation is”. A higher mean score indicated higher sexual identity uncertainty (α = 0.86).

The 11-item Outness Inventory (Mohr and Fassinger 2000) was used to measure degree of outness as an LGB person to other people on an 8-point scale (0 = not applicable; 1 = person definitely does not know about sexual orientation status to 7 = person definitely knows about sexual orientation status, and it is openly talked about). The scale measures the extent to which an individual’s sexual orientation is known by and openly discussed with people, such as “new straight friends”, “work peers”, “mother”, “father”, and “leaders of religious community”. A higher mean score indicated more outness (α = 0.86).

2.2.3. Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlations were performed in IBM SPSS Version 29 to examine associations between the continuous variables. Structural equation modeling with a bootstrap at 1000 samples was then performed in SPSS Amos Version 29 to assess the impact of social triggers on the variance in degree of outness directly and indirectly through the mediation of sexual identity processes. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables in this study.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for Study 1.

2.3.2. Correlations

Table 2 presents the correlations between the continuous variables in this study.

Table 2.

Correlations between continuous variables in Study 1.

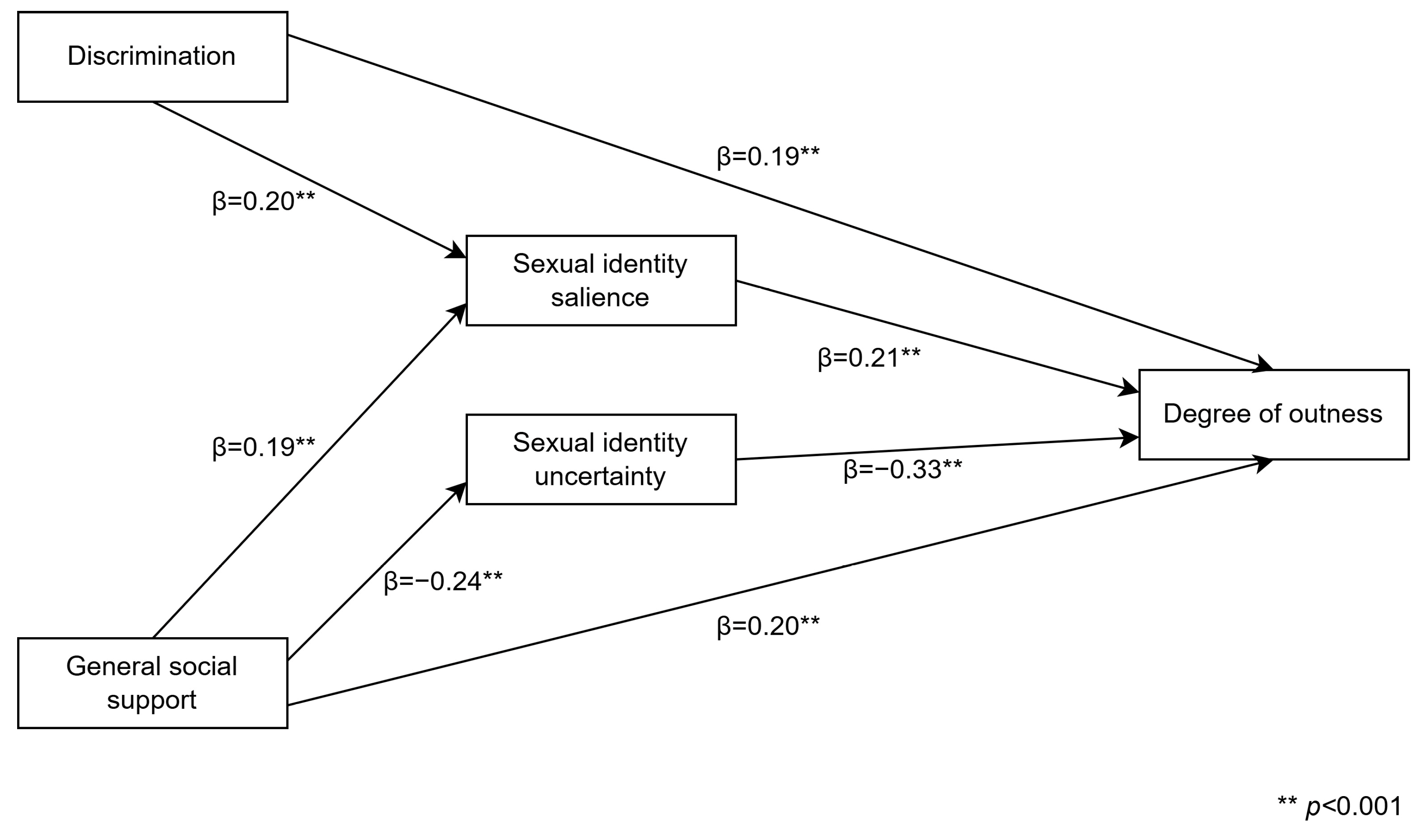

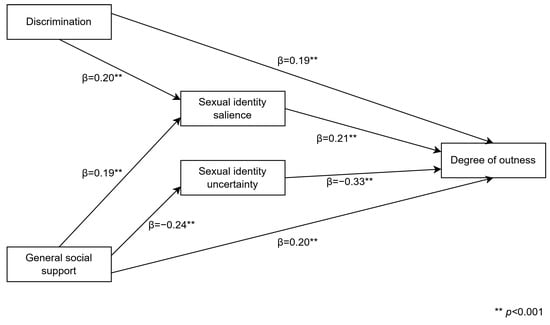

2.3.3. Structural Equation Model

Structural equation modeling (see Figure 2) was performed with a bootstrap at 1000 samples with the main predictors of discrimination and general social support and the mediators of sexual identity uncertainty and sexual identity salience to predict the variance in outness. Model fit was excellent: X2(1, 295) = 0.21, p = 0.64; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RSMEA) = 0.00; Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 1.06; Confirmatory Factor Index (CFI) = 1.00.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model predicting degree of outness in LGB people (Study 1).

First, there was a direct effect of discrimination on outness (β = 0.19, S.E. = 0.10; p < 0.001), as well as an indirect effect through the mediation of sexual identity salience. Discrimination was statistically significantly and positively associated with sexual identity salience (β = 0.20, S.E. = 0.07; p < 0.001), which in turn was statistically significantly and positively associated with outness (β = 0.21, S.E. = 0.08; p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Second, there was a statistically significant direct effect of general social support on outness (β = 0.20, S.E. = 0.12; p < 0.001), as well as mediation effects. General social support was statistically significantly and negatively associated with sexual identity uncertainty (β = −0.24, S.E. = 0.09; p < 0.001), which in turn was statistically significantly and negatively associated with outness (β = −0.33, S.E. = 0.07; p < 0.001). General social support was also statistically significantly and positively associated with sexual identity salience (β = 0.19, S.E. = 0.09; p < 0.001), which was in turn associated with outness. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

3. Study 2

Building on the results of Study 1, Study 2 focuses on associations between social triggers (with discrimination measured differently and including an additional social support variable—LGB social support), different intrapsychic sexual identity processes (sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity), and degree of outness. Moreover, following identity process theory, which posits that individuals attempt to cope with identity threat (Breakwell 2015), interactions between the sexual identity processes (sexual identity threat > sexual identity stigma sensitivity) are also examined.

3.1. Hypotheses

- Discrimination should be directly and positively associated with degree of outness and indirectly associated through sexual identity threat and then sexual identity stigma sensitivity. Following Lopes and Jaspal (2024), discrimination should be positively associated with sexual identity threat, which in turn should be positively associated with sexual identity stigma sensitivity as a self-protective coping strategy. Sexual identity stigma sensitivity should be negatively associated with degree of outness.

- General social support and LGB social support should be directly and positively associated with degree of outness and indirectly associated through sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity. Both forms of social support should be negatively associated with sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity, which in turn should be negatively associated with degree of outness.

3.2. Method

3.2.1. Design, Participants, and Procedure

A total of 156 LGB individuals were recruited using a convenience sampling approach on Prolific to participate in a cross-sectional correlational survey study in 2022. The only inclusion criteria were self-identification as LGB or with another non-heterosexual identity label and being aged 18 or over. There were no missing data, and therefore, all 156 cases were retained for analysis.

Participants indicated their age, gender, and sexual orientation and then completed measures of discrimination, general social support, LGB social support, sexual identity threat, sexual identity stigma sensitivity, and degree of outness. There were 50 (32.1%) self-identified males, 102 (65.4%) females, and 4 (2.6%) individuals who described their gender as “other”. A total of 30 (19.2%) participants self-identified as lesbian, 30 (19.2%) as gay, 67 (42.9%) as bisexual, and 29 (18.6%) as “other”. The participants who reported their sexual identity as “other” did not define their sexual identity in the free text field.

3.2.2. Measures

The 4-item Discrimination Events subscale of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT) Minority Stress Measure (Outland 2016) was used to measure discrimination due to one’s sexual orientation on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never happens to 5 = happens all of the time). The subscale included items such as “I have received poor service at a business because I am LGBT”. A higher mean score indicated higher discrimination due to one’s sexual orientation (α = 0.80).

The 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (Shortened) (Cohen et al. 1985) was used to measure general social support, as in Study 1 (α = 0.89).

The 5-item Community Connectedness subscale of the LGBT Minority Stress Measure (Outland 2016) was used to measure LGB social support on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The subscale included items such as “I feel like I am a part of the LGBT community”. A higher mean score indicated higher LGB social support (α = 0.80).

The 4-item Identity Threat Scale (Breakwell and Jaspal 2022) was adapted to measure sexual identity threat on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The scale included items such as “It undermines my sense of self-worth”, which participants were asked to rate while thinking about their sexual identity. A higher mean score indicated higher sexual identity threat (α = 0.84).

The 3-item Stigma Sensitivity subscale of the LGBIS (Mohr and Kendra 2011) was used to measure sexual identity stigma sensitivity on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The subscale included items such as “I think a lot about how my sexual orientation affects the way people see me”. A higher mean score indicated higher sexual identity stigma sensitivity (α = 0.83).

The 11-item Outness Inventory (Mohr and Fassinger 2000) was used to measure degree of outness as an LGB person to other people, as in Study 1 (α = 0.91).

3.2.3. Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlations were performed in IBM SPSS Version 29 to examine associations between the continuous variables. Structural equation modeling with a bootstrap at 1000 samples was then performed in SPSS Amos Version 29 to assess the impact of social triggers on the variance in degree of outness directly and indirectly through the mediation of sexual identity processes. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables in this study.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for Study 2.

3.3.2. Correlations

Table 4 presents the correlations between the continuous variables in this study.

Table 4.

Correlations between continuous variables in Study 2.

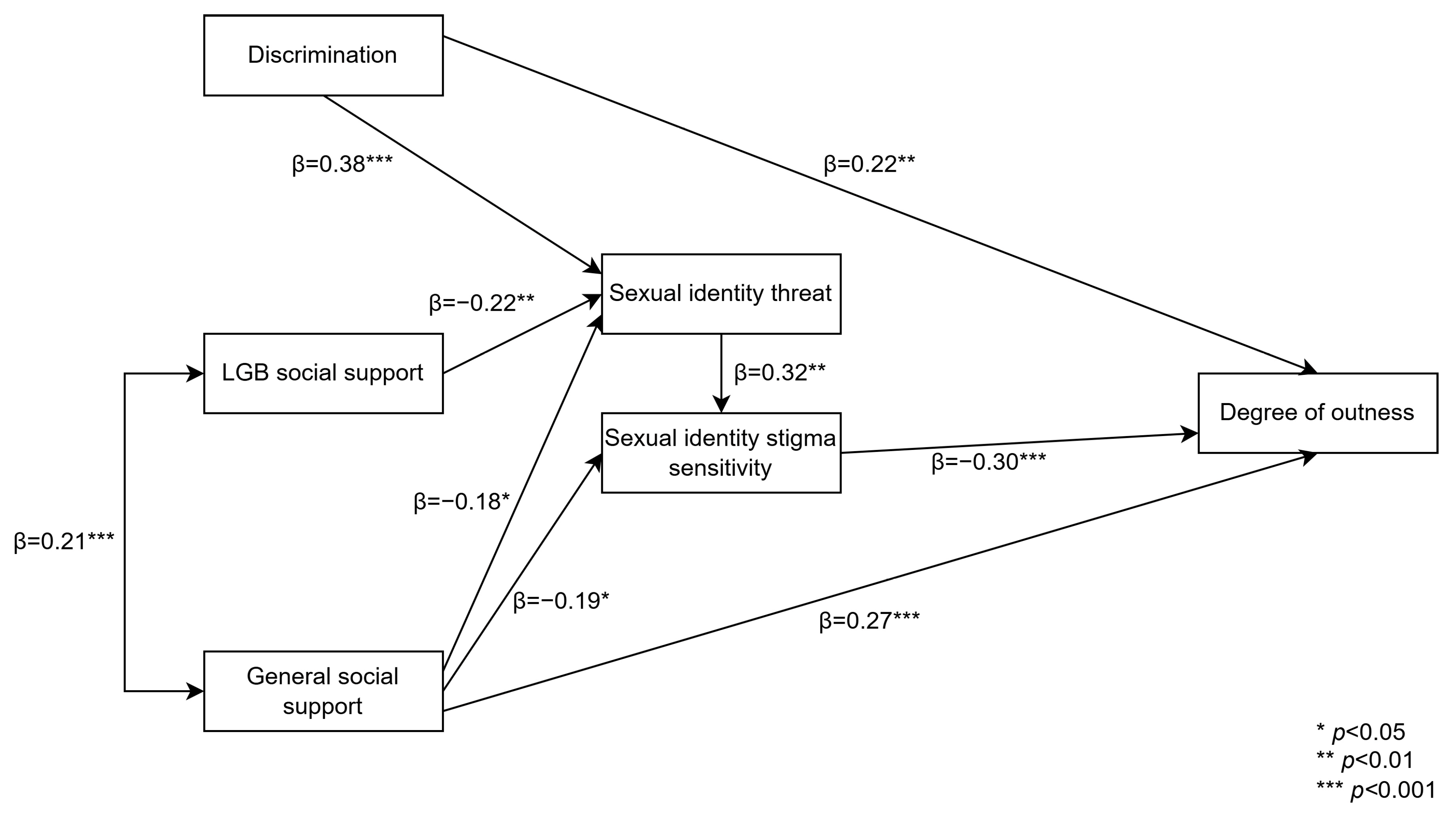

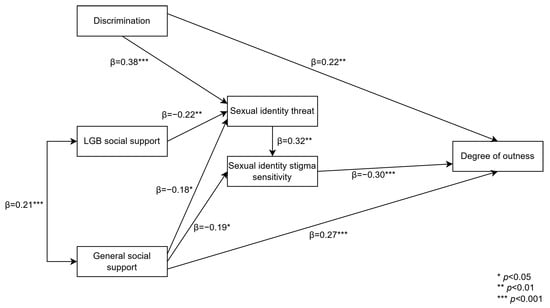

3.3.3. Structural Equation Model

Structural equation modeling (see Figure 3) was performed with a bootstrap at 1000 samples with the main predictors of discrimination, general social support, and LGB social support and the mediators of sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity to predict the variance in outness. Model fit was excellent: X2(2, 156) = 0.49, p = 0.78; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RSMEA) = 0.00; Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 1.10; Confirmatory Factor Index (CFI) = 1.00.

Figure 3.

Structural equation model predicting degree of outness in LGB people (Study 2).

First, the predictors of general social support and LGB social support were statistically significantly and positively correlated (β = 0.21, S.E. = 0.05, p < 0.001).

Second, there was a direct effect of discrimination on outness (β = 0.22, S.E. = 0.17; p = 0.002), as well as an indirect effect through the mediation of sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity. Discrimination was statistically significantly and positively associated with sexual identity threat (β = 0.38, S.E. = 0.11; p < 0.001), which in turn was statistically significantly and positively associated with sexual identity stigma sensitivity (β = 0.32, S.E. = 0.14; p < 0.001). Sexual identity stigma sensitivity was in turn statistically significantly and negatively associated with outness (β = −0.30, S.E. = 0.07; p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Third, there was a statistically significant direct effect of general social support on outness (β = 0.27, S.E. = 0.17; p < 0.001), as well as mediation effects. General social support was statistically significantly and negatively associated with sexual identity threat (β = −0.18, S.E. = 0.12; p = 0.019), which in turn was associated with sexual identity stigma sensitivity and then outness, as described above. In addition, general social support was statistically significantly and negatively associated with sexual identity stigma sensitivity (β = −0.19, S.E. = 0.20; p < 0.015), which in turn as associated with outness, as described above.

Forth, there was no direct effect of LGB social support on outness. However, there were mediation effects. LGB social support was statistically significantly and negatively associated with sexual identity threat (β = −0.22, S.E. = 0.09; p = 0.003), which in turn was associated with LGB stigma sensitivity and then outness, as described above. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

4. Discussion

The two studies generally support the theoretical model predicting degree of outness that is proposed in this article. In both studies, the social triggers of discrimination and general social support were directly and positively associated with outness, but LGB social support was not. Moreover, in Study 1, discrimination was associated with outness through sexual identity salience and general social support was associated with outness through both sexual identity salience and sexual identity uncertainty. In Study 2, discrimination and LGB social support were both associated with outness through sexual identity threat and then sexual identity stigma sensitivity, while general social support was associated with outness through both sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity.

4.1. Discrimination and Sexual Identity Processes

It was predicted that exposure to discrimination would be directly and positively associated with outness, which proved to be true in both studies. It is possible that LGB people who face discrimination proactively seek identity affirmation from others in order to counteract the negative images of their sexuality inherent to discrimination (Jaspal 2025; Jaspal and Breakwell 2022). LGB people may come out strategically, that is, disclose their sexuality to people whom they perceive to be supportive and to an appropriate extent based on the anticipated level of acceptance (e.g., telling somebody one is a lesbian but not necessarily discussing one’s same-sex romantic relationships) (Mohr and Fassinger 2000; Orne 2011). Therefore, they may use their previous experiences of coming out to inform how and to whom they disclose their sexuality in subsequent encounters.

Furthermore, as predicted in Study 1, the relationship between discrimination and outness was mediated by sexual identity salience, suggesting that being exposed to discrimination may render sexual identity more salient in the overall identity structure which in turn is associated with greater outness. It has been shown in previous research in various social group contexts that exposure to discrimination due to a particular identity element (e.g., sexuality, religion, ethnicity) can make the individual more conscious of that identity element (Hughes and Hurtado 2018; Hurtado et al. 2015; Thompson 1999). Identity process theory refers to the assimilation–accommodation process of identity, whereby individuals revise the content and hierarchical structure of their identity content in the face of change (Breakwell 2015). Being exposed to discrimination due to one’s sexuality may generate changes in identity, in this case increasing the salience of sexual identity in particular. Sexual identity salience was in turn positively associated with degree of outness. Indeed, when an element of identity becomes more important to an individual, they will be more inclined to enact and exhibit it to other people (Vignoles et al. 2006). This can enable individuals to experience identity authenticity, which has been found to be an important psychological goal for LGB people in relation to their sexual identity (Riggle et al. 2017).

In Study 2, the relationship between discrimination and outness was mediated by sexual identity threat and then sexual identity stigma sensitivity. It has previously been found that exposure to distal stressors, such as discrimination, is associated with the onset of identity threat because it may deprive the individual of feelings of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness (Lopes and Jaspal 2024). Sexual identity threat was in turn positively associated with sexual identity stigma sensitivity, that is, the anticipatory belief that others will stigmatize them due to their sexuality. As predicted in identity process theory, people who experience identity threat attempt to cope, namely to restore and protect appropriate levels of the undermined identity principles. Sexual identity stigma sensitivity may constitute a self-protective coping strategy. More specifically, the anticipatory belief that others will be stigmatizing may enable the individual to navigate uncertainty and anticipate others’ reactions to their sexuality (see Sedikides and Alicke 2012). This cognition is intended to be self-protective in that one feels more aware of what others may be thinking and can act accordingly. Sexual identity stigma sensitivity was in turn negatively associated with outness, possibly because LGB individuals who believe that they will be stigmatized due to their sexuality are less likely to disclose this identity element to others (Jaspal 2025). Crucially, stigma sensitivity is quite different from actual discrimination. After all, one may face discrimination but still believe that they will be accepted by at least some people. Conversely, sexual identity stigma sensitivity reflects the intrapsychic belief that others are generally stigmatizing.

4.2. Social Support and Sexual Identity Processes

It was predicted that general social support would be directly and positively associated with outness. This hypothesis was supported in both studies. Although discrimination may precipitate the quest for identity affirmation from supportive others, it also appears that having access to more general social support makes it more likely that one will disclose one’s sexuality to others. When people perceive greater interpersonal support from others, they may similarly predict that they will continue to be supported and accepted despite the social stigma attached to their sexuality (Jaspal and Breakwell 2022). Furthermore, although coming out carries some risk of rejection, the belief that one has access to a social support network may provide reassurance that, in the event of rejection, one would continue to derive at least some social support. Although LGB social support was predicted to be directly and positively associated with outness in Study 2, this hypothesis was not supported in the model. The belief that one has a supportive LGB network may have limited impact on one’s decision-making regarding coming out to people who are heterosexual. General support (i.e., from heterosexual people) appears to be key.

Nevertheless, LGB social support was indirectly associated with outness through the mediation of sexual identity threat and then sexual identity stigma sensitivity. In fact, LGB social support proved to be a more important predictor of lower sexual identity threat than general social support which was also negatively associated with sexual identity threat. Indeed, it has been shown that involvement in the LGB community constitutes an important step in sexual identity development (Cass 1979; Morris 1997). Having access to an LGB support network can enable LGB people to exchange confidences, potentially providing exposure to positive images of their sexuality which in turn may bolster feelings of self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness. LGB people are generally socialized in a heteronormative context in which heterosexuality is constructed as the norm and LGB identities are stigmatized. Social support from other LGB people may counteract heteronormativity and thus enable individuals to derive a positive sense of self based on their sexuality, precluding sexual identity threat.

In Study 2, general social support was negatively associated with both sexual identity threat and sexual identity stigma sensitivity. Social support has been found to enhance self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness (e.g., Guan and So 2016; Kinnunen et al. 2008; Rosenberg 1965; van Tilburg et al. 2019) and may therefore prevent sexual identity threat. Furthermore, the existence of a supportive social network may preclude the anticipatory belief that others are generally dismissive of one’s sexuality (i.e., stigma sensitivity). Indeed, in their study of gay men’s identity, Jaspal and Breakwell (2022) found that social support was negatively correlated with the perception that others held negative attitudes about their sexuality. Moreover, as demonstrated in Study 1, general social support appears to be protective against sexual identity uncertainty and conducive to sexual identity salience. LGB people with a general support network may be more likely to assimilate-accommodate their sexuality in their overall sense of identity (high identity salience) and to append stable meaning and value to it (low identity uncertainty). Social support may make people feel that they can explore and discuss issues relating to sexuality with supportive others (Brandon-Friedman and Kim 2016). This argument is also consistent with the positive relationship observed between access to social support and identity authenticity (Alchin et al. 2024).

4.3. Limitations

First, the studies used a cross-sectional correlational survey design, and thus, it is not possible to ascertain causal relationships between the variables. The theoretical model should also be tested in experimental and longitudinal research building on these studies. Second, the studies provide insight into the role of general social support and, in Study 2, also LGB social support. As Brandon-Friedman and Kim (2016) found differences in sexual identity processes by type of social support, it would be valuable to include additional sources of social support, such as support from heterosexual people, specifically, family, friends, and one’s intimate partner, as predictors in future research. Third, since discrimination is a common distal stressor, this was the focus of the present studies. As overt discrimination itself becomes increasingly stigmatized, other subtler minority stressors (e.g., microaggressions) have emerged and have been found to have similarly negative effects for identity and wellbeing in LGB people. They should be examined in future tests of the theoretical model. Forth, people vary in their coping styles (Jaspal et al. 2022). In addition to sexual identity stigma sensitivity, other possible coping strategies should be examined, including those that are more adaptive and sustainable in the long term. Finally, this study focuses on sexual identity disclosure only. It would be valuable to test the model in relation to the disclosure of gender identity among transgender, non-binary, and gender-diverse people who also experience a coming out process (Brumbaugh-Johnson and Hull 2019).

4.4. Practical Implications

In spite of its potential risks, coming out can have many social and psychological benefits for LGB people. When LGB people are out, they are more visible, and their identities can be understood, accepted, and supported. This can serve to create a socio-cultural context in which it is easier to come out as LGB. It may also make the experience of being and coming out as LGB less isolating and threatening (Breakwell and Jaspal 2022; Cass 1979). Moreover, positive intergroup contact is associated with greater support for LGB people’s rights among heterosexual people (Reimer et al. 2017), but positive intergroup contact is dependent on LGB people’s willingness to disclose their sexuality to others.

It is recommended that counseling and social interventions focus on facilitating access to varied types of social support. There is evidence that LGB social support performs the important function of preventing the psychologically harmful experience of sexual identity threat. Therefore, LGB people should be supported to connect with other community members, which, incidentally, has also been recognized as an important stage of the Cass (1979) model of LGB identity development and as a facilitator of psychological wellbeing in subsequent research (Milton and Knutson 2023; Morris et al. 2001). Social support from other LGB people with potentially overlapping identity experiences may provide access to more positive images of one’s sexuality, facilitating its successful assimilation–accommodation and positive evaluation as an element of identity. This is especially important in view of the threatening position occupied by LGB people, that is, the high risk of threats to self-esteem, self-efficacy, continuity, and positive distinctiveness that they face. Indeed, discrimination—a commonly experienced distal stressor—was found to be associated with sexual identity threat. LGB social support may operate as a protective factor in the face of exposure to such stressors (Lopes and Jaspal 2024).

The results also underline the importance of general social support (in addition to LGB-specific social support), which may enable LGB people to come out more and also protect against a wider range of maladaptive sexual identity processes, such as sexual identity uncertainty, threat, and stigma sensitivity, all of which may be impediments to coming out. Research in various group contexts shows that people who are stigmatized due to a particular identity element (e.g., sexuality, ethnicity, religion) may disengage from the general population and immerse themselves in their ingroup (Heikamp et al. 2020; Lyons-Padilla et al. 2015; Wegner 2014). In doing so, stigmatized individuals perhaps seek a safe space in which they can protect their sense of self. Counseling and social interventions should facilitate access to more varied social support networks among LGB people beyond the LGB community alone.

The social trigger (and distal stressor) of discrimination was found to be related to sexual identity salience. Sexual identity salience can motivate LGB people to seek out supportive others who will be accepting of their sexual identity. They should be supported to achieve functional outness (Silveira et al. 2022) so that the experience can provide identity affirmation, including exposure to positive images of their sexuality (Orne 2011). However, a potential impediment may be the experience of sexual identity threat, which was found to mediate the relationship between discrimination and outness in Study 2. Identity process theory notes that any given event or experience (in this case, discrimination) may be threatening to some but not to others (Breakwell 2015). LGB people who possess the social and psychological resources (e.g., resilience, self-esteem, access to a social support network) to resist identity threat may feel more empowered to share their sexual identity with others (Jaspal 2025; Jaspal and Breakwell 2022). Counseling interventions can help build these social and psychological resources to prevent the experience of sexual identity threat upon exposure to stressors.

Counseling psychology interventions should focus on supporting LGB people to come out in ways that promote psychological wellbeing. Interventions that incorporate components of mindfulness, emotional regulation, self-compassion, and self-esteem may be especially valuable in promoting favorable intrapsychic sexual identity processes which in turn may increase the likelihood of coming out (e.g., Bluth and Neff 2018; Ferrari et al. 2019). The coming out process can often be perceived as isolating, especially in the context of discrimination and negative reactions (e.g., Breakwell and Jaspal 2022). Ali and Lambie (2019) show the particular effectiveness of strengths-based counseling to support the coming out process (see also Olesen et al. 2017). In view of the findings of the present studies that social support is key and that negative intrapsychic processes can impede coming out, group counseling may be an especially valuable approach to facilitating social support (Olesen et al. 2017; Yalom and Leszcz 2005). Group counseling can enhance coping strategies (Meaney-Tavares and Hasking 2013) and promote personal growth (Ali and Lambie 2019).

5. Conclusions

The findings of the two studies presented in this article provide support for the proposed theoretical model of coming out. Social triggers, such as discrimination and access to social support, appear to be associated with sexual identity processes, which in turn are related to degree of outness. Innovative counseling interventions should focus on facilitating access to varied social support and on preventing or alleviating sexual identity threat in the face of minority stressors. In addition to innovating counseling psychology to better support LGB clients in relation to coming out, the battle against LGB discrimination in all its guises must continue.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Schools of Business, Law and Social Sciences Ethics Committee at the University of Brighton (REF: 2021/13 20 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in these studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data for these studies are openly accessible on OSF at the following link: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FV493.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LGB | Lesbian, gay, and bisexual. |

| LGBT | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. |

Note

| 1 | This article focuses exclusively on the disclosure of sexual identity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. It does not examine the separate issue of gender identity disclosure among transgender and non-binary people. |

References

- Akers, Whitney P., Craig S. Cashwell, and Susan D. Blake. 2021. Images of resilience: Outness in same-gender romantic relationships. Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling 15: 168–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchin, Carolyn E., Tanya M. Machin, Neil Martin, and Lorelle J. Burton. 2024. Authenticity and inauthenticity in adolescents: A scoping review. Adolescent Research Review 9: 279–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Shainna, and Glenn W. Lambie. 2019. The impact of strengths-based group counseling on LGBTQ + young adults in the coming out process. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 23: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, Edward, M. A. Cornish, and M. A. Hanks. 2021. Predicting relationship satisfaction in LGBQ + people using internalized stigma, outness, and concealment. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 17: 356–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejakovich, Tamara, and Ross Flett. 2018. “Are you sure?”: Relations between sexual identity, certainty, disclosure, and psychological well-being. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 22: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, Karen, and Kristin D. Neff. 2018. New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self and Identity 17: 605–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Friedman, Richard A., and Hea-Won Kim. 2016. Using social support levels to predict sexual identity development among college students who identify as a sexual minority. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 28: 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, Glynis M. 2015. Coping with Threatened Identities. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell, Glynis M., and Rusi Jaspal. 2022. Coming out, distress and identity threat in gay men in the United Kingdom. Sexuality Research & Social Policy 19: 1166–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumbaugh-Johnson, Stacey M., and Kathleen E. Hull. 2019. Coming out as transgender: Navigating the social implications of a transgender identity. Journal of Homosexuality 66: 1148–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, Vivienne C. 1979. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality 4: 219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Robin Mermelstein, Tom Kamarck, and Harry M. Hoberman. 1985. Measuring the functional components of social support. In Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. Edited by Irwin G. Sarason and Barbara R. Sarason. New York: Springer, pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dyar, Christina, Brian A. Feinstein, and Bonita London. 2015. Mediators of differences between lesbians and bisexual women in sexual identity and minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2: 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, Leandre R., Duane T. Wegener, Thomas I. Vaughan-Johnston, Laura E. Wallace, and Richard E. Petty. 2019. Designing and interpreting replication studies in psychological research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Consumer Psychology. Edited by Frank Kardes, Paul M. Herr and Norbert Schwarz. New York: Routledge, pp. 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, Brian A., Ethan H. Mereish, Mary R. Mamey, Cindy J. Chang, and Jeremy T. Goldbach. 2023. Age differences in the associations between outness and suicidality among LGBTQ+ youth. Archives of Suicide Research 27: 734–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, Madeleine, Caroline Hunt, Ashish Harrysunker, Maree J. Abbott, Alissa P. Beath, and Danielle A. Einstein. 2019. Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness 10: 1455–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, David M., and Ilan H. Meyer. 2023. Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology 51: 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Mengfei, and Jiyeon So. 2016. Influence of social identity on self-efficacy beliefs through perceived social support: A social identity theory perspective. Communication Studies 67: 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikamp, Tobias, Karen Phalet, Colette Van Laar, and Karine Verschueren. 2020. To belong or not to belong: Protecting minority engagement in the face of discrimination. International Journal of Psychology 55: 779–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, Jordan D. X., Xochitl de la Piedad Garcia, Leah M. Kaufmann, Yasin Koc, and Joel R. Anderson. 2022. A systematic and meta-analytic review of identity centrality among LGBTQ groups: An assessment of psychosocial correlates. Journal of Sex Research 59: 568–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Bryce E., and Sylvia Hurtado. 2018. Thinking about sexual orientation: College experiences that predict identity salience. Journal of College Student Development 59: 309–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, Sylvia, Adriana Ruiz Alvarado, and Chelsea Guillermo-Wann. 2015. Thinking about race: The salience of racial identity at two- and four-year colleges and the climate for diversity. The Journal of Higher Education 86: 127–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, Rusi. 2025. Minority stressors, social connectedness and degree of outness in gay men: Data from two cross-sectional correlational studies in the United Kingdom. Sexuality and Culture, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, Rusi, and Glynis M. Breakwell, eds. 2014. Identity Process Theory: Identity, Social Action and Social Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal, Rusi, and Glynis M. Breakwell. 2022. Identity resilience, social support and internalized homonegativity in gay men. Psychology and Sexuality 13: 1270–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, Rusi, Moubadda Assi, and Ismael Maatouk. 2022. Coping styles in heterosexual and non-heterosexual students in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Social Psychology 37: 33–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, Marja-Liisa, Taru Feldt, Ulla Kinnunen, and Lea Pulkkinen. 2008. Self-esteem: An antecedent or a consequence of social support and psychosomatic symptoms? Cross-lagged associations in adulthood. Journal of Research in Personality 42: 333–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, Nicole, Richard M. Ryan, and Netta Weinstein. 2012. Is coming out always a "good thing"? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science 3: 145–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Barbara, and Rusi Jaspal. 2024. Identity processes and psychological wellbeing upon recall of a significant “coming out” experience in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. Journal of Homosexuality 71: 207–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons-Padilla, Sarah, Michele J. Gelfand, Hedieh Mirahmadi, Mehreen Farooq, and Marieke Van Egmond. 2015. Belonging nowhere: Marginalization and radicalization risk among Muslim immigrants. Behavioral Science & Policy 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaney-Tavares, Rebecca, and Penelope Hasking. 2013. Coping and regulating emotions: A pilot study of a modified dialectical behavior therapy group delivered in a college counseling service. Journal of American College Health 61: 303–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Ilan H. 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin 129: 674–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, Cole, and Douglas Knutson. 2023. Family of origin, not chosen family, predicts psychological health in a LGBTQ+ sample. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 10: 269–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, Jonathan J., and Matthew S. Kendra. 2011. Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology 58: 234–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, Jonathan J., and Ruth Fassinger. 2000. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 33: 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Jessica F. 1997. Lesbian coming out as a multidimensional process. Journal of Homosexuality 33: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, Jessica F., Craig R. Waldo, and Esther D. Rothblum. 2001. A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, John, Jean Campbell, and Michael Gross. 2017. Using action methods to counter social isolation and shame among gay men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 29: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orne, Jason. 2011. ‘You will always have to “out” yourself’: Reconsidering coming out through strategic outness. Sexualities 14: 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outland, Pearl L. 2016. Developing the LGBT Minority Stress Measure. Fort Collins: Colorado State University. Available online: https://mountainscholar.org/items/54cd061c-1505-4122-acf9-2494d6465a68 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ratcliff, Jennifer J., Jamie M. Tombari, Audrey K. Miller, Peter F. Brand, and James E. Witnauer. 2022. Factors promoting posttraumatic growth in sexual minority adults following adolescent bullying experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP5419–NP5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, Nils K., Julia C. Becker, Angelika Benz, Oliver Christ, Kristof Dhont, Ulrich Klocke, Sybille Neji, Magdalena Rychlowska, Katharina Schmid, and Miles Hewstone. 2017. Intergroup contact and social change: Implications of negative and positive contact for collective action in advantaged and disadvantaged groups. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 43: 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, Marc E. S., Nickaella B. Bautista, Gemaima R. A. Betos, Kirkby I. S. Martin, Sophia Therese N. Sapio, Ma Criselda T. Pacquing, and John Manuel R. Kliatchko. 2023. In/out of the closet: Perceived social support and outness among LGB youth. Sexuality & Culture 27: 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggle, Ellen D. B., Sharon S. Rostosky, Whitney W. Black, and Dani E. Rosenkrantz. 2017. Outness, concealment, and authenticity: Associations with LGB individuals’ psychological distress and well-being. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 4: 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohy, Valerie. 1996. Displacing desire: Passing, nostalgia and Giovanni’s Room. In Passing and the Fictions of Identity. Edited by Elaine K. Ginsberg. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 218–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Morris. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanscartier, Shayne, and Geoff MacDonald. 2019. Healing through community connection? Modeling links between attachment avoidance, connectedness to the LGBTQ+ community, and internalized heterosexism. Journal of Counseling Psychology 66: 564–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, Constantine, and Mark D. Alicke. 2012. Self-enhancement and self-protection motives. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation. Edited by Richard M. Ryan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 303–22. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, Aline P., Elder Cerqueira-Santos, and Aline Nogueira de Lira. 2022. Outness profiles and mental health in Brazilian lesbian women: A cluster analysis. Sexuality Research & Social Policy 19: 1496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, David, James McAbee, Kia Åsberg, and Ashley McGee. 2015. Coming out and the potential for growth in sexual minorities: The role of social reactions and internalized homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality 62: 1512–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, Vetta L. S. 1999. Variables affecting racial-identity salience among African Americans. Journal of Social Psychology 139: 748–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, Michael T, and Toni L. Bisconti. 2021. Age differences in sexual minority stress and the importance of friendship in later life. Clinical Gerontologist 44: 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Tilburg, Wijnand A. P., Constantine Sedikides, Tim Wildschut, and Ad J. J. M. Vingerhoets. 2019. How nostalgia infuses life with meaning: From social connectedness to self-continuity. European Journal of Social Psychology 49: 521–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoles, Vivian L., Camillo Regalia, Claudia Manzi, Jen Golledge, and Eugenia Scabini. 2006. Beyond self-esteem: Influence of multiple motives on identity construction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90: 308–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, Susan E., Sakkaphat T. Ngamake, Witsinee Bovornusvakool, and Steven V. Walker. 2016. Discrimination, internalized homophobia, and concealment in sexual minority physical and mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 3: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Laurel B., Brandon Velez, Raquel S. Craney, and Sydney K. Greenwalt. 2022. The cost of visibility: Minority stress, sexual assault, and traumatic stress among bisexual women and gender expansive people. Journal of Bisexuality 22: 513–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Ryan. 2014. Homonegative Microaggressions and Their Impact on Specific Dimensions of Identity Development and Self-Esteem in LGB Individuals. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/6d89f5782dd2cc9c06edf00d73c7afca/1?cbl=18750&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- White, Darcy, and Rob Stephenson. 2014. Identity formation, outness, and sexual risk among gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Men’s Health 8: 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, David R., Yan Yu, James S. Jackson, and Norman B. Anderson. 1997. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology 2: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Stacey L., Sheri L. LaDuke, Kathleen A. Klik, and David W. Hutsell. 2016. A paradox of support seeking and support response among gays and lesbians. Personal Relationships 23: 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Wenjian, Lijun Zheng, Yin Xu, and Yong Zheng. 2017. Internalized homophobia, mental health, sexual behaviors, and outness of gay/bisexual men from Southwest China. International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalom, Irvin, and Molyn Leszcz. 2005. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 5th ed. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).