1. Introduction

Creative thinking skills are not only related to the arts but also to problem solving, which is fluid and situation-specific, so pupils need to be able to be flexible, to transfer their experiences, and apply them to a given solution (

Braun 2012;

Razzouk and Shute 2012;

Müller-Roterberg 2018). At its simplest, design thinking was defined by the interaction design foundation as follows: “It is a method that helps us understand the user, challenge assumptions, and reframe the problem to find alternative solutions that are not clear” (

Guzhavina 2017, p. 160). It is considered in finding effective means of transition to new trends in the use of teaching methods and tools. Today, the development of non-standard methods and the development of thinking during their use in teaching children has a special place (

Zhdanova 2016). For teachers to educate children according to the needs of each pupil, they need to be empathetic themselves, and it is important to develop this capacity in teachers by reflecting on their personal experiences.

Design thinking is an analytical and creative process that allows the individual to experiment, create, gather feedback, and redesign. Design thinking requires creativity, the ability to visualize content, and the flexibility to adapt to the learner’s needs (

Razzouk and Shute 2012). All these qualities of design thinking are essential for the teacher of the future.

Batraeva and Kazajkina (

2015) defined that “design thinking is a type of thinking that has a certain amount of special knowledge (constructive, artistic, etc.), as well as a non-standard approach to reality and the way of life in it” (p. 49). Thinking design methodology includes five stages, which are carried out step by step: empathy, focus, the generation (and selection) of ideas, prototyping, and testing (

Kaziev and Igembaeva 2022). Empathy involves being sympathetic to other people’s feelings and understanding what bothers them and why. You cannot do anything wrong with this kind of empathy, and you do not even need to start using the method because this empathy forces you to put aside your own experiences, moods, and beliefs and allows you to look at the problem through another person’s eyes. Among the tools that serve as auxiliary tools at this stage are external observation, in-depth interviews, expert interviews, analog studies, and user experience (

Kaziev and Igembaeva 2022).

Empathy is critical in the work of an educator. Therefore, empathy as one of the creative thinking skills of future teachers will be explored in this paper. A teacher should always look for the most comfortable and acceptable solution for his/her pupils. To understand what is important to learners, they must explore their experiences and expectations, understand the learning process, and acquire the knowledge that helps them learn. Through conversations with learners, the teacher observes what questions they ask, what concerns them, and what areas of the content they have doubts about. The teacher analyzes pupils’ behavior when they are working independently, for example, cooperatively doing work with classmates (

Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė 2021;

Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė et al. 2021).

2. The Importance of Teachers’ Empathy in the Educational Process

Contemporary educational practice increasingly focuses on teachers’ social–emotional competence, of which empathy is one component. Teachers’ ability to be empathetic depends on the quality of their interactions with their pupils, which is an important prerequisite for developing pupils’ cognitive abilities and developing their social relationships, sense of trust, and emotional security (

Sun et al. 2023;

Díaz-Narváez et al. 2024;

Martín de Hijas-Larrea et al. 2025). Teacher empathy is a particularly promising factor in explaining teacher–student interaction quality, especially emotional support for pupils, which is essential throughout the educational process in any educational content methodology.

Zhou’s (

2022) analysis of research on empathy helped to identify key themes related to the concept of empathy: learning about a student’s mental states or emotions (‘cognitive’ empathy); feeling, experiencing, or being affected by a student’s emotions (‘affective’ empathy); empathy as a character trait or a tendency to be empathic (as opposed to a one-off action that happens to depend on the situation); and showing care or concern towards a pupil. Caring for students and building positive teacher–student relationships is a key part of teachers’ professional role (

Watt et al. 2021;

Aldrup et al. 2022). In addition, providing high levels of emotional support, as indicated by a positive emotional tone in the classroom, being sensitive to students’ emotional, social, and academic needs, and being responsive to their interests are aspects of a high-quality classroom (

Pianta and Hamre 2009). To achieve this, reading students’ non-verbal signals, in other words, empathy is essential. Empathetic teachers will be aware that students may feel anxious when faced with complex tasks or ashamed and frustrated when they consistently fail to answer the teacher’s questions. Once teachers have identified students’ negative affective states, affective empathy should motivate them to be sensitive to their emotional needs and provide comfort and encouragement (

Weisz et al. 2020). The prosocial classroom model (

Jennings and Greenberg 2009;

Jennings 2015) also integrates these ideas and further argues that teachers’ social–affective competence, in which empathy is a component, should facilitate classroom management.

Various research studies have shown that schoolteachers who were better at perceiving others’ emotions were more optimistic about their teaching performance (

Wu et al. 2019;

Aldrup et al. 2022), while other studies have linked teachers’ empathy with their qualifications (in terms of self-confidence and perception of others) (

Ghanizadeh and Moafian 2010;

Khodadady 2012;

Aldrup et al. 2022).

Abacioglu et al. (

2019) found that primary school teachers who were more optimistic about their promise reported using more culturally and socially sensitive teaching practices. Similarly, teachers who reported a more remarkable ability to perceive other people’s emotions perceived their attentiveness to students’ needs as more pronounced (

Nizielski et al. 2012). Furthermore, teachers who reported greater empathy were likelier to choose emotionally supportive strategies in response to a hypothetical student with challenging behaviors (

Gottesman 2016;

Kyriazis et al. 2018).

In situations where the teacher judges that their empathy is appropriate, they demonstrate observable signs of behavioral empathy. Conversely, if the teacher feels that demonstrating empathy would be impractical, he or she may refrain from demonstrating empathy with students. This is because empathizing with others requires cognitive effort, and under challenging circumstances, individuals may choose to avoid empathy altogether (

Cameron et al. 2019). Similarly, teachers may avoid empathy in specific scenarios based on their assessment of the potential consequences of expressing empathy (

Sun et al. 2023). As a teacher’s competence increases, he or she becomes better equipped to recognize students’ emotions quickly, leading to a more positive learning environment and better learning outcomes. In addition, social factors such as perceived similarity and familiarity play an important role in this threefold model of empathy (

Cikara et al. 2011;

Main et al. 2017;

Sun et al. 2023). However, educators also experience stress, which may be heightened based on certain circumstances (

Baker et al. 2021;

Koslouski 2022), making adopting new initiatives challenging. Given the high prevalence of potentially traumatic events in children’s lives (

Bethell et al. 2017), the negative consequences of trauma on learning (

Perfect et al. 2016), and the knowledge of effective practices to promote learning for these students (

Sun et al. 2023), increased attention to the well-being of students and educators may provide an opportunity to catalyze change and support in educational settings to increase educational practices that provide a safe environment and promote empathic behavior in both teachers and students.

3. Research Methodology and Organization

Research hypothesis: prospective teachers are more empathetic in situations related to their immediate environment and daily life than in situations from the formal study environment.

Research questions:

In which situations can prospective teachers empathize and show attention to another person?

Which situations help preservice teachers identify their own experiences when thinking about the ability to empathize with the role of the other, and what are the conditions and dispositions for expressing empathy?

Research instrument. Our study used a set of questions developed using the diagnostic method of empathic abilities (based on

Boiko 1996).

Appendix A presents the full

Boiko (

1996) test questionnaire we used. In this paper, we analyzed only the results of those questions that were statistically significant in our study. The questions were adapted to the students of pedagogy and their experiences. Only those related to the expression of empathic abilities were selected, i.e., they are designed to assess the ability to empathize and understand the thoughts and feelings of another person. Empathy is the meaningful knowledge of the other person’s inner world with whom one is interacting. It is understood that another person can empathize with other people’s states of being if they have experienced something similar, so it is natural to expect that students, future primary teachers, should be able to empathize with the role of a primary pupil since they have been children. The human capacity for empathy increases with life experience, so the students chosen were 2nd- and 3rd-year students with experience in pedagogical studies. The future teachers’ responses to the research questions or statements were analyzed according to specific areas of empathy (see

Table 1) and whose statistical validity was confirmed by our study on the empathy abilities of future teachers:

In response to the statements in

Table 1, students indicated one if they agreed and zero if they disagreed; the students of the Pedagogy degree program were asked to reflect on their own experience and to agree with the statement if it is close to their experience or to disagree with it if it does not correspond to the students, prospective teachers, experience, or attitudes on the issue under analysis. This calculation was chosen based on Boiko’s methodology (

Boiko 1996).

Participants in the study. Students of one Kazakh university training teacher in the 2nd–3rd year of the Bachelor’s degree program “Pedagogical Sciences”, aged between 18 and 35 years, were 34 men and 80 women (114 persons total). The age and gender distribution of the participants (see

Table 2) are as follows:

Table 2 shows that more women than men participated in the study. Most participants were aged 18 and 19; 27 were in their 20s. This is natural, as all the participants were 2nd- and 3rd-year education students. Therefore, the participants were young people who had not yet had much life experience, and their answers to the statements analyzed in the study would be related to their personal experience and behavior but not to their role as educators.

Time and place of the survey. The research was conducted in March–April 2024 during the spring semester of the course “Methodology of Constructive Teaching” of one of the Bachelor’s degree programs of “Pedagogical Sciences” in the University of Kazakhstan, after the lectures on empathy in the course.

Data analysis method. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. The data analysis used a descriptive approach, counting the responses selected by the prospective teachers. Internal consistency reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the reliability of the scale. This paper reports the study results when Cronbach’s alpha was more significant than 0.70 and the

p-value was <0.05 (

Dikčius 2011;

Pakalniškienė 2012). Only those questions or statements that were answered positively (indicating empathy) by more than 50% of the participants are included in the article.

In the data analysis part of the empirical study of the article, the number of responses chosen by the future teachers for each option is presented, which will allow us to see the future teachers’ attitudes towards the expression of empathy according to the three groups under study (the conditions and dispositions for the expression of empathy, the ability to empathize with the other, and the identification of the expression of empathy). A higher number of answers chosen by the respondents means a more frequent application to a specific situation.

All the empathy statements given to the prospective teachers were in paper form, and the students of educational studies handwrote the answers to the questions. The survey was organized in Kazakh. Due to the limited scope of the paper, only a partial analysis of the data from the study related to the expression of empathy is presented.

Ethics of research. The study was carried out by informing the participants of the study’s objectives, stressing that the ethical requirements of the study would be respected and that the data would, therefore, be analyzed anonymously. In addition, the conduct and procedures of the study were reviewed by the Ethics Committee of the University of Kazakhstan, which approved the conduct of the study on doctoral students in the field of education (protocol № 2, 13 February 2024).

4. Analysis of Results

We will present the data from the empirical study according to the three domains of empathy: the conditions and attitudes for expressing empathy, the ability to empathize with others, and situations identifying the development of empathy. Each area was assigned several statements (see

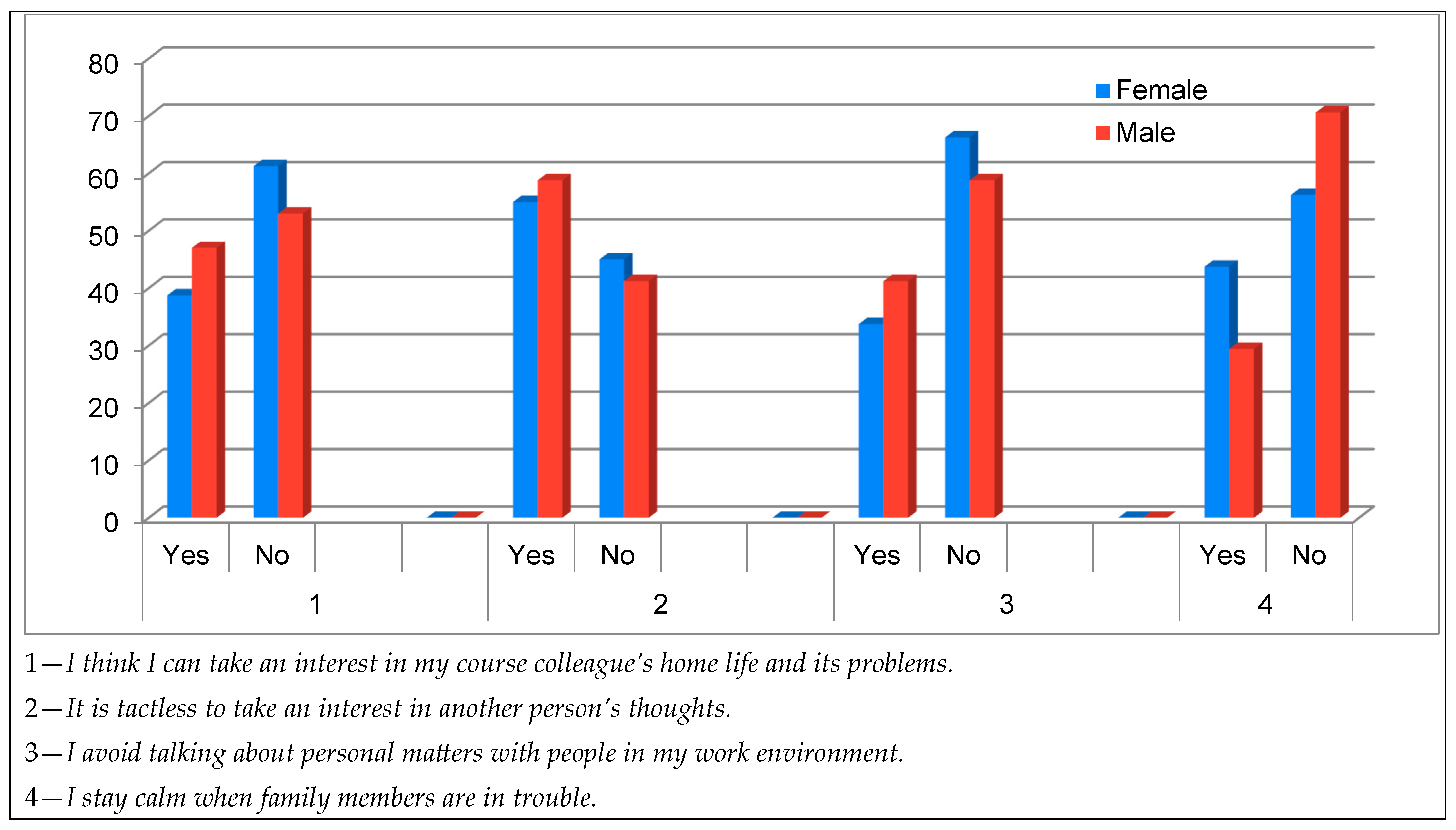

Table 1), which were rated one if the statement was close to the participant’s behavior or attitudes and two if the statement did not reflect the participant’s experience. The participants’ attitudes towards the conditions and the expression of empathy are illustrated in

Figure 1.

The responses in

Figure 1 show that the prospective teachers did not shy away from talking to colleagues about their lives outside the university (as shown by the responses to statement 3). This is a positive feature for future teachers, as conversations with colleagues (other future teachers) will be about the content of education and broader issues related to personal life outside the learning environment. It is about developing and fostering relationships between teachers because, in a community of teachers, positive relationships are built when teachers not only interact within the institution but also when they travel with their families, meet in informal settings, spend their leisure time together, and thus get to know each other better and help each other better. In addition, most of the participants could not react calmly if someone close to them is in trouble, although, as future teachers, they will have to learn to react calmly even if there are problems in the class. The fact that the participants did not yet have a great deal of life experience is shown by the answers to statement 2 (It is tactless to take an interest in another person’s thoughts), as more than half of the participants said that it is tactless to take an interest in another person’s thoughts, in his or her inner world. However, it is possible to do so tactfully when the emotional conditions are safe, and the individuals can open up to talk things out. As future teachers, students are expected to be able to tell them what makes them happy and what depresses them. The answers to the question about interest in another person’s home life were very similar to those about interest in the person’s inner world. More participants in the study said they could not take an interest in their colleague’s home life. The answers to this statement show that one still needs to gain experience and learn to communicate as educators on this issue.

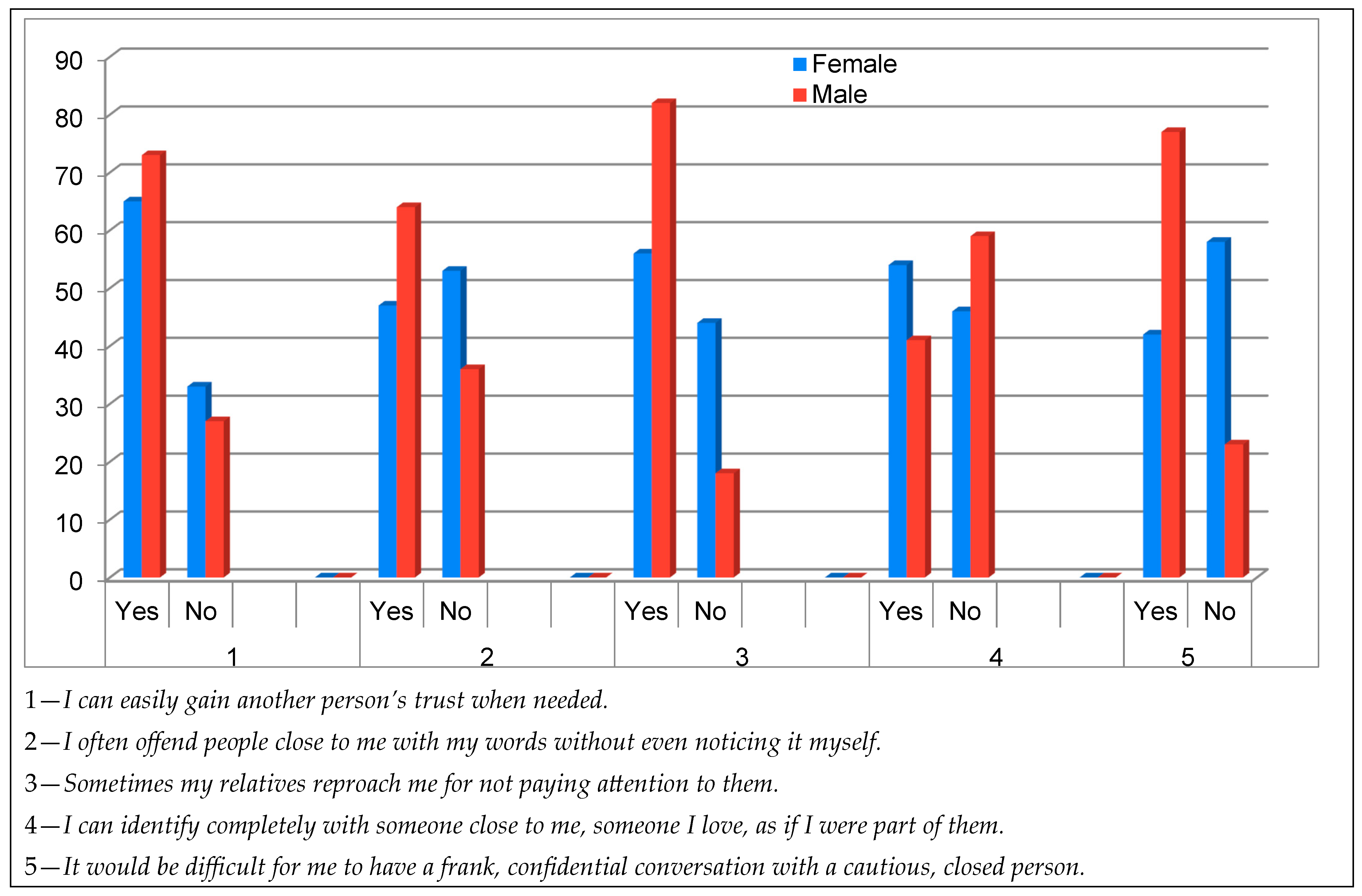

The study was interested in the situations in which future teachers can empathize with others. The participants’ responses in this area are shown in

Figure 2:

According to the data in

Figure 2, some of the statements related to the ability to empathize with others were answered similarly by the prospective teachers. In contrast, others were answered very differently if we analyze their answers by gender. The most striking differences were statements 3 (Sometimes my relatives reproach me for not paying attention to them) and 5 (It would be challenging to have a frank, confidential conversation with a cautious, closed person). More than half of the women in the study said their relatives sometimes reprimand them for not paying attention, and 80% of the male future teachers agreed. This means that more females are paying attention to their relatives. This may also be related to the country’s culture, where women are the guardians of the family heart. At the same time, men may be expected to shoulder more responsibilities and, therefore, have more objections from their close environment, as the participants are very young and still being educated by their close environment. The responses of each gender to statement 5 were positive, as over 70% of female prospective teachers said they would find common ground with a cautious, closed person. This is very important, as there is a wide variety of pupils in the teaching profession, and the attitude and ability to relate to all, including close children, is an important attribute. Most of the study participants could quickly gain another person’s trust. This shows that future teachers are flexible and adaptable to the situation. The distribution of responses to statement 2 (I often offend people close to me with my words without even noticing it myself) shows that the participants in the study are young, sometimes not in control of their speech or not paying enough attention to it. More self-care and self-discipline are needed in this area, as verbal expression is important in pedagogical work, so that one’s word does not become an excessive and unjust punishment for children. More women (half of the participants) than men could identify with someone close to them. This means that they can analyze another person’s behavior as their own. This is noteworthy because this quality is important in pedagogical work and will likely be developed by future teachers as they gain experience.

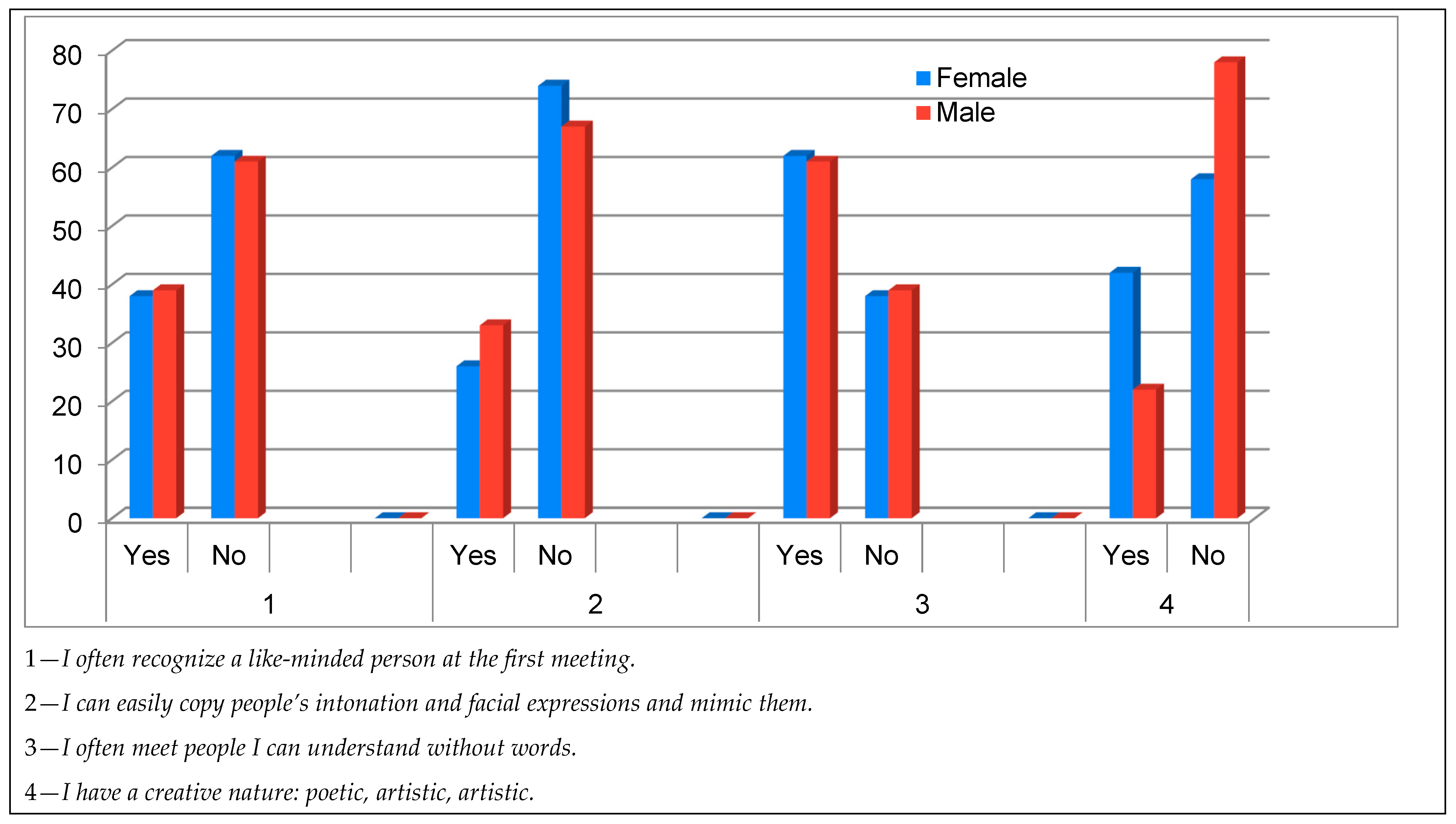

As the study is concerned with the expression of empathy by preservice teachers, it was asked what situations identify this element (see

Figure 3).

Analyzing the data in

Figure 3, we can say that for statements 1 (I often recognize a like-minded person at the first meeting) and 3 (I often meet people I can understand without words), there was an overlap in the opinions of the participants according to gender, as the same proportion of participants (both women and men) responded. The answers to the first statement should be considered positive because it takes time to get to know someone well, and the first meeting can only give a preliminary impression. The answers to the 3rd statement show that more than 60% of the participants know body language well and can understand people without words. This is a valuable quality in an educator, allowing them to manage the class and create a positive rapport.

The responses to statement 2 (I can easily copy people’s intonation and facial expressions and mimic them) and statement 4 (I have a creative nature: poetic, artistic, artistic) show that the participants responded honestly to the statements, as the answers to the statements with similar content were very similar. The data suggest that these future teachers may be more inclined towards the exact sciences, disciplined, and have creativity in the arts and problem solving. As they are 2nd- and 3rd-year students, they will still have opportunities to improve their competencies in artistic subjects in the following semesters.

To summarize the empirical data, we can say that future teachers are more empathetic than non-empathetic, able to know the body language of individuals and to understand others without words, reacting emotionally to disasters in their immediate environment, and sometimes not controlling their vocabulary in the immediate environment (they may unintentionally offend others). It is important to mention that the prospective teachers answered the survey statements honestly, as the answers to the cross statements were very close. In addition, some of the answers also reflected the young age of the prospective teachers (most of the participants were under 20 years old), as they rely on their personal experience and interactions with family and friends and have had very little direct teaching work. They will become even more empathetic after their teaching practice and several years of work. However, they have already revealed their potential for empathy as sufficient during this study.

5. Discussion

An ever-expanding field of abilities enriches design thinking. The student gradually learns to work with familiar objects in new ways to introduce them to new connections. In addition, educational activity is enriched by activating intellectual and mental powers through design thinking. Thus, design thinking is an approach to problem solving that, in its classical version, consists of specific systematic actions consisting of empathy and focus, the generation and selection of ideas, and developing and testing an education product. As a result, a product that meets the requirements of the given task and is aimed at the end user is obtained (

Sun et al. 2023;

Martín de Hijas-Larrea et al. 2025). It is important that throughout the education process, the teacher is empathetic, attentive to each learner’s needs and abilities, supportive, motivating, and helpful (

Fullan 2019,

2020;

Fullan and Gallagher 2020). We can only do all this if educators are willing and able to help children to grow and develop, to respond to changing situations, to embrace each learner, and to empathize and understand the context of each learner, not only in progressive moments but also when they need support in every way. Teachers can only help pupils if they know them well, know their strengths, and are interested in the world around them and their environment. To do all this, teachers need to be empathetic. The quality of empathy requires an interpersonal interaction between the teacher and pupil based on mutual trust (

Sun et al. 2023;

Martín de Hijas-Larrea et al. 2025). Similarly to our research, similar medical student studies also found that females are more empathic than males regarding their immediate environment (

Díaz-Narváez et al. 2024).

The whole school community benefits if a school has empathetic and progressive teachers (

Fullan et al. 2020). Education occurs in a learning partnership in a physically and emotionally safe environment (

Fullan and Quinn 2020). Our data show that more than half of the people in our study, the future teachers, should be able to work in such an environment because they are not afraid to get to know others, to empathize with their roles, to reassure or to speak up, and to understand people without words. As the participants in the study were very young, it is likely that by the time they have completed their pedagogical studies and gained more experience, they will be even more empathetic and willing to get to know others. Empathetic educators can organize contemporary educational practices in which pupils develop creative skills. Pupils should receive theoretical knowledge and practical activities necessary to begin to develop in the creative process. They can tackle creative tasks without fear, quickly transfer knowledge from one area to another, and engage in visual and subject modeling. Design thinking is based on developing a harmonious combination of creative, artistic, and constructive thinking in theoretical and practical lessons, which will give a strong impetus to students’ development regardless of the specific field of activity in the future (

Borankulov 2023). Educational practices based on a safe environment can only be created by educators who have developed empathy and continuously improve these skills (

Zhegallo et al. 2023).

6. Conclusions

By directly holding classes aimed at developing design thinking, children’s age and individual characteristics are taken into account, and an individual approach is chosen for each of them, using traditional and innovative methods. For the educational process to be successfully organized and implemented in educational practice, the educators who educate children should be highly qualified and willing to listen to each child’s individual needs, which means that future educators should be empathetic. In order to be so, they should be willing to improve themselves and, in some cases, to be more disciplined and to be an example to other members of society, and all of this is something that needs to be learned, which is why studies such as the one we have presented should also take place at the end of the pedagogical studies and after they have started their pedagogical work. It would then be possible to observe how teachers’ attitudes and skills in empathy have changed. The hypothesis raised in our study was partially confirmed because most future teachers said they could often understand people without words. However, in their immediate environment, they often show too little attention to those closest to them or use offensive words directed at them. This is related to the age and experience of the participants in the study, and it is, therefore, necessary to develop empathy skills continuously by paying attention to the people around them.

7. Limitations of the Study

Our study of empathy among preservice teachers in Kazakhstan was conducted at a university. Although our study’s findings are valid and reliable, it does not mean that all Kazakhstani prospective teachers are the same in terms of empathy as in the study we presented. In order to draw generalized conclusions, it would be necessary to carry out the same kind of complementary research in all Kazakhstani universities that prepare future teachers.

Although we have presented data on empathy expression among preservice teachers from one university, it is significant because it shows where they are already advanced in empathy and where they still need to improve. Moreover, the data can already be used as a basis for other similar studies and for comparing how prospective teachers’ empathy abilities are changing.

Author Contributions

Methodology, D.J.-S.; Software, D.J.-S.; Validation, R.A. and D.J.-S.; Formal analysis, R.A.; Data curation, R.A.; Writing—original draft, R.A.; Writing—review & editing, D.J.-S.; Visualization, D.J.-S.; Supervision, D.J.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A study conducted at the Doctor of Education programme at Kyzylorda Korkyt Ata University in Kazakhstan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Kazakhstan (protocol code №2, 13.02. 2024 and date of approval 13 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to

ksu@korkyt.kz.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Methodology for diagnosing the level of empathy (Boiko 1996) Empathy Test Questionnaire)

Please rate whether you have the following traits and whether you agree with the statements (answer “yes” or “no”).

Test questions

1. I habitually scrutinize people’s faces and behavior to understand their character, inclinations, and abilities.

2. If those around me show nervousness, I usually remain calm.

3. I trust the reasoning of my intellect more than my intuition.

4. It is appropriate for me to take an interest in my co-workers’ domestic problems.

5. I can quickly gain a person’s trust if necessary.

6. I usually guess a ’soul mate’ in a new person from the first meeting.

7. Out of curiosity, I usually start a conversation about life, work, and politics with random fellow travelers on a train or plane.

8. I lose my mental balance if people around me are oppressed by something.

9. My intuition is a more reliable means of understanding others than knowledge or experience.

10. Showing curiosity about the inner world of another person is tactless.

11. I often hurt people close to me with my words without noticing it.

12. I can easily imagine myself as an animal and feel its habits and states.

13. I rarely reason about the reasons for the actions of people who are directly related to me.

14. I rarely take to heart the problems of my friends.

15. I usually feel that something must happen to someone close to me within a few days, and expectations are fulfilled.

16. In communication with business partners, I usually avoid discussing personal matters.

17. Sometimes, my relatives reproach me for callousness and inattention to them.

18. I can easily copy people’s intonation and facial expressions, imitating them.

19. My curious look often confuses new partners.

20. Other people’s laughter usually infects me.

21. Often, acting at random, I nevertheless find the right approach to a person.

22. Crying with happiness is foolish.

23. I can completely merge with a loved one, as if dissolved in him.

24. I have rarely met people I would understand without unnecessary words.

25. I unwittingly or out of curiosity, often overhear strangers’ conversations.

26. I can remain calm even if everyone around me is worried.

27. It is easier for me to subconsciously feel the essence of a person than to understand him, ’laying it out on the shelves.’

28. I calmly relate to minor troubles that happen to family members.

29. It would be difficult for me to have a heartfelt, confidential conversation with a wary, withdrawn person.

30. I have a creative nature—poetic, artistic, artistic.

31. I listen to the confessions of new acquaintances without much curiosity.

32. I get upset if I see a person crying.

33. My thinking is more characterized by concreteness, rigor, and consistency than intuition.

34. When friends start talking about their troubles, I prefer to turn the conversation to another topic.

35. If I see that someone close to me is not well at heart, I usually refrain from asking.

36. I find it hard to understand why trifles can upset people so much. |

References

- Abacioglu, Ceren Su, Monique Volman, and Agneta H. Fischer. 2019. Teacher interventions to student misbehaviors: The role of ethnicity, emotional intelligence, and multicultural attitudes. Current Psychology 40: 5934–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrup, Karen, Bastian Carstensen, and Uta Klusmann. 2022. Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes. Educational Psychology Review 34: 1177–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Courtney N., Haley Peele, Monica Daniels, Kathleen Whalen, and Stacy Overstreet. 2021. The Experience of COVID-19 and Its Impact on Teachers’ Mental Health, Coping, and Teaching. School Psychology Review 50: 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batraeva, Jekaterina Sergejevna, and Oksana Sergejevna Kazajkina. 2015. Formation of design thinking among students in additional education [Formirovanie dizajnerskogo myshleniya u obuchayushihsya v usloviyah dopolnitelnogo obrazovaniya]. Young Scientist Molodoj Uchenyj 10: 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, Christina D., Narangerel Gombojav, Michael Davis, Scott P. Stumbo, and Kathleen Powers. 2017. Issue Brief: Adverse Childhood Experiences Among US Children. Baltimore: Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Boiko, Viktor Vasilievich. 1996. The Energy of Emotions in Communication: Looking at Yourself and Others [Энергия эмoций в oбщении: взгляд на себя и на других]. Moscow [Мoсква]: Filin Information and Publishing House [Инфoрмациoннo-издательский дoм Филинъ]. [Google Scholar]

- Borankulov, Erkinbek. 2023. Effective ways to develop creativity in an individual. Bulletin of L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University—Pedagogy, Psychology, Sociology Series 143: 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Tim. 2012. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation [Dizain-myshlenie: Ot razrabotki novykh produktov do proektirovaniia biznes-modelei]. Moscow: Mann, Ivanov & Ferber, p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, C. Daryl, Cendri A. Hutcherson, Amanda M. Ferguson, Julian A. Scheffer, Eliana Hadjiandreou, and Michael Inzlicht. 2019. Empathy is hard work: People choose to avoid empathy because of its cognitive costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 148: 962–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikara, Mina, Emile G. Bruneau, and Rebecca Saxe. 2011. Us and Them: Intergroup Failures of Empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20: 149–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikčius, Vytautas. 2011. Principles of Questionnaire Design [Anketos sudarymo principai]. Vilnius: Vilnius University. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Narváez, Victor P., Joyce Huberman-Casas, Jorge Andrés Nakouzi-Momares, Chris Alarcón-Ureta, Patricio Alberto Jaramillo-Cavieres, Maricarmen Espinoza-Retamal, Blanca Patricia Klahn-Acuña, Leonardo Epuyao-González, Gabriela Leiton Carvajal, Mariela Padilla, and et al. 2024. Levels of Empathy in Students and Professors with Patients in a Faculty of Dentistry. Behavioral Sciences 14: 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, Michael. 2019. Nuance: Why Some Leaders Succeed and Others Fail. Thousand Oaks: Corwin. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, Michael. 2020. Learning and the pandemic: What’s next? Prospects 49: 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, Michael, and Joanne Quinn. 2020. How Do Disruptive Innovators Prepare Today’s Students to Be Tomorrow’s Workforce?: Deep Learning: Transforming Systems to Prepare Tomorrow’s Citizens. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, Michael, and Mary Jean Gallagher. 2020. The Devil Is in the Details: System Solutions for Equity, Excellence, and Student Well-Being. Thousand Oaks: Corwin. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, Michael, Joanne Quinn, Max Drummy, and Mag Gardner. 2020. Education Reimagined: The Future of Learning. Available online: https://edtech.moe.gov.bn/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Microsoft-Education-Reimagined-Paper.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Ghanizadeh, Afsaneh, and Fatemeh Moafian. 2010. The role of EFL teachers’ emotional intelligence in their success. ELT Journal 64: 424–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, Dana E. 2016. Preparing Teachers to Work with Students with Emotional Regulation Difficulties. Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Guzhavina, Anastasia Eduardovna. 2017. Features of the development of design thinking in adolescence [Osobennosti razvitiya dizainerskogo myshleniya v podrostkovom vozraste]. Modern Issues of Teaching Methods Sovremennye voprosy metodiki prepodavaniya 1: 160–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, Daiva. 2021. A study of language and cognitive aspects in primary school pupils’ and teachers’ activities through cooperative learning. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 21: 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakavonytė-Staškuvienė, Daiva, Aušra Žemgulienė, and Emilija-Alma Sakadolskis. 2021. Cooperative learning issues in elementary education: A Lithuanian case study. Journal of Education Culture and Society 12: 445–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Patricia A. 2015. Early childhood teachers’ well-being, mindfulness, and self-compassion in relation to classroom quality and attitudes towards challenging students. Mindfulness 6: 732–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Patricia A., and Mark T. Greenberg. 2009. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research 79: 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaziev, Karas Orzanovic, and Kamshat Sovetovna Igembaeva. 2022. Empatiia—pedagogikalyq orіstegі basqarushylardyn manyzdy sapasy retіnde [Empathy as an Important Quality of Managers in Pedagogical Sphere]. Iasaui universitetіnіn habarshysy 2: 124, 143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadady, Ebrahim. 2012. Emotional intelligence and its relationship with English teaching effectiveness. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 2: 2061–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslouski, Jessica B. 2022. Developing empathy and support for students with the “most challenging behaviors:” Mixed-methods outcomes of professional development in trauma-informed teaching practices. Frontiers in Education 7: 1005887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, Nicholas, Theodore Metaxas, and Emmanouil M. L. Economou. 2018. War for profit: English corsairs, institutions and decentralized strategy. Defence and Peace Economics 29: 335–51. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10242694.2015.1111601?journalCode=gdpe20 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Main, Alexandra, Eric A. Walle, Carmen Kho, and Jodi Halpern. 2017. The Interpersonal Functions of Empathy: A Relational Perspective. Emotion Review 9: 358–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín de Hijas-Larrea, Leire, Irati Ortiz de Anda-Martín, and Ariane Díaz-Iso. 2025. Teaching with Ears Wide Open: The Value of Empathic Listening. Education Sciences 15: 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Roterberg, Christian. 2018. Handbook of Design Thinking: Tips and Tools for How to Design Thinking. Seatle: Kindle Direct Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nizielski, Sophia, Suhair Hallum, Paulo N. Lopes, and Astrid Schutz. 2012. Attention to student needs mediates the relationship between teacher emotional intelligence and student misconduct in the classroom. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 30: 320–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakalniškienė, Vilmantė. 2012. Establishing the Reliability and Validity of the Study and Assessment Tools [Tyrimo ir įvertinimo priemonių patikimumo ir validumo nustatymas]. Vilnius: Vilnius University. [Google Scholar]

- Perfect, Michelle M., Matt R. Turley, John S. Carlson, Justina Yohanna, and Marla Pfenninger Saint Gilles. 2016. School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health 8: 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, Robert C., and Bridget K. Hamre. 2009. Conceptualization, measurement, and improvement of classroom processes: Standardized observation can leverage capacity. Educational Researcher 38: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzouk, Rim, and Valerie Shute. 2012. What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important? Review of Educational Research 82: 330–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Binghai, Yaoyao Wang, Qun Ye, and Yafeng Pan. 2023. Associations of Empathy with Teacher–Student Interactions: A Potential Ternary Model. Brain Sciences 13: 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, Helen M. G., Ruth Butler, and Paul W. Richardson. 2021. Antecedents and consequences of teachers’ goal profiles in Australia and Israel. Learning and Instruction 80: 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, Erika, Desmond C. Ong, Ryan W. Carlson, and Jamil Zaki. 2020. Building empathy through motivation-based interventions. Emotion 21: 990–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yingying, Kunyu Lian, Peiqiong Hong, Liu Shifan, Rong-Mao Lin, and Rong Lian. 2019. Teachers’ emotional intelligence and self-efficacy: Mediating role of teaching performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 47: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhdanova, Nadezhda Sergeyevna. 2016. Organization of scientific research of students in the field of graphic design [Organizatsiya nauchnyh issledovanii studentov v oblasti graficheskogo dizaina]. In Creative Space of Education: Collection of Materials from an Intra-University Conference [Tvorcheskoe prostranstvo obrazovaniya: Sbornik materialov vnutrivuzovskoi konferentsii]. Magnitogorsk: MGTU, pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhegallo, Alexander, Ivan A. Basyul, and Andrey Vlasov. 2023. The Relations of Constructs Measured by the Boyko Empathy Questionnaire and the em in Questionnaire. Eksperimental’naya psikhologiya. Experimental Psychology 16: 203–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Ziqian. 2022. Empathy in Education: A Critical Review. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 16: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).