Abstract

Performance methodologies take many forms—performative writing, poetic transcription, and co-performative witnessing, to name only a few—and can be both process and product, differentiating and unifying a group between and across differences. As a social work researcher committed to decolonial, liberatory methodologies that make and bring meaning to the communities I work with, performance methodologies fill a gap that other qualitative research methods can only begin to approach. This project is an exploration in performance methodologies and Critical Suicidology through the lens of social work research, with a case study derived from a performance documenting suicide prevention research with Native Hawaiians. This study sought to understand connections between suicide risk and experiences of colonization among Native Hawaiians and among LGBTQ Native Hawaiians. The findings point to the importance of relationships, cultural understandings of identity and identification, and healing through cultural practices. Sections from the performative text, including voices from the participants, as well as feedback gathered from performances of the research, are woven together with academic narrative to form a creative and critical report of the research.

1. Introduction

Among many Indigenous populations in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, the impacts of colonization have been studied through the lens of historical trauma, and many suicide researchers acknowledge and account for the impacts of colonization on the suicide rates within the community (Booth 1999; Kral 2012; Kral and Idlout 2016; Liu and Alameda 2011; Hatcher 2016; Hunter and Harvey 2002; Wexler 2009). This approach to understanding suicide is a distinct departure from contemporary suicidology, where a “medical model” has been utilized for the understanding of suicide since the mid-1950s (Browne et al. 2005). Indigenous scholars (Duran 2006; Stoor et al. 2015), however, are challenging dominant/Western perspectives on suicide and are calling for cultural and historical understandings of suicide to gain insight into risks for suicidality (Burrage et al. 2016). In light of these emergent shifts in the field of suicidology, this paper examines suicide risks and protections among Indigenous populations from an actively decolonial lens. With a specific focus on suicide among Native Hawaiians, this paper explores the impacts of cultural identity, intersectionality, and colonization on Native Hawaiian mental health.

From 2001 to 2011, suicide was the leading cause of fatal injury (surpassing falls, drownings, and traffic accidents) for Hawaii residents 15–74 years of age (Galanis and Tani 2019; Hawaii State Department of Health 2012). Overall, suicide rates in Hawaii have been rising since Hawaii began collecting data, in 1908 (Else and Andrade 2008). Suicide rates and trends are disproportionately high among Native Hawaiians in Hawaii, compared to other ethnic groups, and fall into many of the same patterns that are experienced by other Indigenous communities globally, including high levels of suicide clusters, a peak in suicide risk between the ages of 15 and 24, and a three times higher risk of suicide for males than females (Hawaii State Department of Health 2012). As a queer mestiza Filipina social worker in Hawaii, the level of suicidality among the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and māhū1 (LGBTQM) Native Hawaiian youth communities was of particular concern to me throughout my nine years in community-based mental health work. After examining the issues through the lens of youth risk and resiliency using evidence-based practices and training programs, many questions remained unanswered.

In November 2015, I began a research project in Hawaii to gather stories from six Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) who had partnered with me on suicide prevention projects over the years. “Towards liberation, kuleana, and hope: Native Hawaiian perspectives on colonization and suicidality” was a qualitative phenomenology designed to capture Native Hawaiian lived experiences with colonization and perspectives on the impacts of colonization on LGTBQM Native Hawaiians. When I returned to my home institution (not in Hawaii), the stories weighed heavily on me. How could I share these experiences—experiences of brownness and queerness and colonial trauma and hope—within the words, walls, and Whiteness of an academic institution? How could I help the stories become more than qualitative transcripts—coded and networked into anonymity—which presumed to speak an objective truth? How could I interrogate the subjecthood that “suicidal” implies, particularly for resistant subjects of a colonial state?

2. Background

Performance methodologies and Critical Suicidology led me to my answers. Through the critical, active, and reflexive space that performance can create, the theories and praxis of performance methodologies emboldened me and clarified my vision. The integration of Critical Suicidology (e.g., Kral 2012; Kral and White 2017; White 2007, 2015, 2017; White et al. 2016) as a theoretical lens provided additional support for examining suicide among Kānaka Maoli from critical, intersectional, and socio-political–historical perspectives (Alvarez et al. 2020). Inspired by the quote, “because we cannot know, write, or stage it “all” we are free to create a vision of what is possible” (Holman Jones 2005, p. 768), I began to conceptualize a utopian performance of the research project that was open, unsolved, vulnerable. Through performance, I could create space for the nuance of the stories that I heard, while also reproducing the strength and clarity each storyteller maintained. In what Madison (2012) terms a “performance of possibilities” (p. 190), I could design a performance experience that integrated the stories from the participants, feedback from the audience members as co-performative witnesses, and critical reflections from myself, the performer, as I embodied the data.

Performance is a reflective strategy, an articulation of experience, a rehearsal in resistance that critically exposes the status quo and has the potential to create and direct policy (Miller-Day 2008). Performances (including poems, plays, staged readings, or performances of conversational texts) can be used as alternatives to or as complementary scholarly representations or research publications (Denzin 2003) and are increasingly utilized in qualitative research projects. Social scientists apply theories of performance to ethnographic research (Conquergood 2002; Denzin 2003; Madison 2005), and theories of performance have been used in sociology, education, and communication studies and have, infrequently, been applied in the allied health professions (Smith and Gallo 2007) and social work (Shimei et al. 2016).

Smith and Gallo (2007) describe the utility of performance ethnography in nursing, including a case example of a performance text created from interviews with 86 families of children with genetic conditions. The text includes the parents’ voices in dialogue as they share their histories, challenges, and triumphs while caring for their children with genetic conditions. As a performance methodology, “material from reflexive interviews creates dialogue that leads to performances in which multiple voices can be heard, dichotomies are resisted, differences are brought to the foreground, and the audience is responsible for interpreting the performance” (Smith and Gallo 2007, p. 523). The text is intimate, shares new knowledge, and allows the reader to be motivated or moved to action or reflection based on their own personal identities and experiences. It is a powerful example of a “complementary form of research publication” (Denzin 2003, p. 13), and a compelling strategy for research dissemination in the health fields. Smith and Gallo (2007) suggest that performative texts can be useful in health fields for both research and practice purposes. They describe the benefits of performance texts to help a patient better understand a new diagnosis and to learn from other people’s stories who have experienced the same condition. Students and faculty, too, can gain from these methods and the creation of new knowledge through lived experiences. Ultimately, Smith and Gallo argue that the whole community—patients, providers, and researchers alike—can benefit from sharing meaningful dialogue in this way.

Shimei et al. (2016) present a performative text that is a dialogue between a group of social work students and faculty processing critical social work theory through sharing personal and professional experiences in the field of critical social work. Their stories and reflections are interwoven with a “voice of theory,” (Shimei et al. 2016, p. 616), which is a quote or series of quotes from scholars who have created important foundational texts in social work literature. The application of this performance methodology allows for the explicit connections between theory and practice to emerge through personal story-sharing and reflection on behalf of participants and readers alike. Even the article itself can act as a performative intervention when read or performed aloud with a group and can facilitate discussions about critical reflexivity, theories, and praxis. In this way, Shimei et al. (2016), demonstrate the ways that performance and performative texts have implications for social work research, teaching, and practice.

In an example of cross-disciplinary work that spans health, communication, and education, Miller-Day (2008), describes a research project and performance, HOMEwork, that focused on working-poor mothers and the middle school-age children they were supporting. The performance included statistics from the quantitative surveys used in the communities and discussions of current policies and practices that were affecting the families on a daily basis, and it concluded with four direct action steps that individuals and communities could take to affect change (Miller-Day 2008). Through dialogue (during and post-performance), broader members of the community and other stakeholders engaged with the materials and action steps and followed Denzin’s (2006) guiding principles, with a commitment to community action. Performance is an under-utilized but powerful methodology for social work broadly and, with the explicit surfacing of power, social injustices, and multi-voiced reflections on ethical practice, may be particularly suited for critical social work (Shimei et al. 2016).

Critical Suicidology. Critical Suicidology is a developing theoretical framework for understanding suicide that has been conceptualized by a group of scholars who challenge dominant perspectives on suicide and suicide risk. Jennifer White, a self-proclaimed suicidology misfit (White 2015), proposed what she calls “Critical Suicidology” (White 2017, p. 473), as an approach to suicide rooted in compassion for the individual who is suffering, which simultaneously facilitates the interruption of structural, social, historical, colonial, and political violence that fosters inequity and vulnerability among certain populations. Emphasizing qualitative, community-based, and multidisciplinary research, Critical Suicidology is a departure from the quantitative, clinical focus of modern suicidology (Hjelmeland 2016). Specifically, Critical Suicidology theory shifts from an individualized and problem-centered understanding of suicidality to a structural and social understanding of suicidality. With explicit connections to feminist, post-structuralist, anti-racist, postcolonial, and other critical theories (Kral and White 2017), Critical Suicidologists utilize a structural analysis that challenges oppression and oppressive frameworks. As such, Critical Suicidologists argue that Indigenous suicide must be understood within the cultural and community context in which it is occurring (Kral and Idlout 2016; Wexler and Gone 2016), and researchers should utilize culturally grounded approaches to understanding the etiology of and interventions for suicidality. Emphasizing qualitative, community-based, and multidisciplinary research, Critical Suicidologists are calling for a departure from the Western, clinical focus of modern suicidology research (Hjelmeland 2016).

Culture and Critical Suicidology. Assumptions about suicide may not be culturally congruent within Indigenous communities. There are socially produced and culturally maintained perspectives on both the risks of and protections from suicide within Indigenous communities that need to be taken into consideration (Wexler and Gone 2016). For example, some Indigenous youth consider suicide an acceptable demonstration of distress in the context of familial and interpersonal conflict (Kral and Idlout 2016). Wexler and Gone (2016) call for three primary strategies to respond more effectively to suicide issues in Indigenous communities. First, they implore suicide prevention professionals to consider that suicide can be an expression of personal and social suffering. An examination of the community, family, and social context that surrounds a suicide is a necessary step in Indigenous communities. Second, they challenge the assumption that medical, clinical approaches to healing, prevention, and intervention are the only and/or most effective forms of treatment. Rather, suicide-related interventions with Indigenous communities should be relational and grounded in interpersonal and social prevention strategies, rather than solely based in clinical approaches to treatment. And lastly, they argue that contemporary suicidology should strive not to recolonize and retraumatize Indigenous community members through rapid, clinical responses to suicide crises (Wexler and Gone 2016). Instead, efforts to prevent suicide in Indigenous communities should be driven by the sovereign, decolonial needs and desires of the communities themselves. Each of these strategies will be taken into consideration throughout the current examination of suicide among Native Hawaiians (Alvarez et al. 2020).

3. Case Example: (Re)performing Queerness in Indigenous Community

The goals of this study were to identify Native Hawaiian perspectives on the impact of colonization on Native Hawaiians and LGBTQM Native Hawaiians. In the context of decolonization, as a non-Hawaiian researcher, I have a particular responsibility not to exacerbate these risks and to be responsive to the needs of the community members themselves. This inquiry was guided by Native Hawaiian community partners, and the work continues to be informed by their feedback. The primary research question, How do Native Hawaiian and LGBTQM Native Hawaiian adults living in Hawaii define and describe their experiences with colonization?, drove a qualitative examination of life and death in modern day Hawaii. The following case example describes the development, findings, and dissemination of a research project exploring the impacts of colonization on Native Hawaiian and LGBTQM Native Hawaiian suicide risk. Experiences of co-performative witnessing were captured through a reflection worksheet that was distributed to participants who were watching the research performance and analyzed for theory and content, which are included in the case example.

4. Methods

The data consisted of six interviews with cisgender/heterosexual Native Hawaiian and LGBTQM Native Hawaiians on Oahu, Hawaii, between November and December 2015. All of the participants identified as Hawaiian or part-Hawaiian (n = 6). Two-thirds of the participants (n = 4) identified lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or māhū, and the remaining third were cisgender and heterosexual (n = 2) Three of the participants identified as female or wahine (female), two participants identified as male, and one identified as transgender. Participants were recruited through the researcher’s existing relationships with members from Native Hawaiian and LGBTQM Native Hawaiian communities, including colleagues from suicide prevention, mental health, HIV/AIDS prevention, and bullying prevention organizations throughout the state of Hawaii. The data collection process consisted of semi-structured interviews, guided by a qualitative protocol with additional prompts and follow-up questions. A small number of the interviews were conducted on the phone (n = 2), and the remainder occurred in person (n = 4) and were audio recorded. The interviews were transcribed by the researcher, and the completed transcripts were sent to participants for review upon request, for feedback or corrections that were (re)integrated. The interviews lasted for approximately one hour and thirty minutes each. Each participant received food and beverages and a gift card. Participants were asked to describe their earliest experiences, as well as their most recent experiences, with colonization and how they remembered learning about it. They were asked to reflect on how they have been impacted by these experiences throughout their life. They discussed the role that colonization might play in Native Hawaiian and LGBTQM Native Hawaiian suicide. Risks for the initial qualitative phenomenology were minimal and deemed exempt by the University of Denver IRB, protocol #816085-1. Each participant provided written consent to engage with the study.

In addition to these research data, I also gathered data during the research dissemination process. These data were from anonymous participants who attended workshops and presentations of the research project and verbally consented to their de-identified data being included in the work. The inclusion of these data—in the form of dialogic worksheets, poems, and comments—demonstrates the power and potential impacts of performative methods. I describe the process of feedback gathering as “co-performative witnessing,” the details of which are included in the Section 5.

5. Findings

From this research, three main constructs emerged: risks, rites, and resistance. Using the language of the participants, these constructs gave way to three overarching themes that encompass much of the meaning and lived experience that the stories told. Each theme will be described, followed by a “talking story” segment, which contains a narrative from an interview with a participant that highlights the themes described.

Risks: “It depends on the family.” Participants described the great importance of their immediate family in decisions, perspectives, and even the kinds of questions they could ask. Complicated and often mixed messages about race and skin color, gender and sexuality, and suicide were woven through every interview. Many participants described maintaining close—if conflicted—relationships with their family members as their highest priority.

Rites: “Making a kīhei.” A kīhei is a traditional cloth draped and tied over one shoulder. It is typically worn at graduations and other ceremonies, and the patterns are infused with good intentions, important connections, and deep meaning. The theme of the kīhei was used to describe the intentional and often ritualistic process that participants engaged in to (re)connect to Hawaiian culture. Through collaboration with colonization (one participant described having a “colonized mind”), or as the result of heteronormative beliefs and practices reinforced by churches and other institutions, many participants were not able to see their roles in modern day Native Hawaiian culture until they understood it as their rite. Several described the exclusion of LGBTQM Native Hawaiians from Native Hawaiian cultural spaces as increasing the sense of disconnection from their cultural rites and potentially signaling erasure from Native Hawaiian history.

Resistance: “The return of Lono.” Lono is the Native Hawaiian god of growth, healing, agriculture, and abundance (Pukui et al. 1972). Called upon when the hard work of planting and farming has been done, Lono is welcomed home by the Makahiki festivals, which are times of peace, rest, fertility, and harvest. One participant described it as “a Native Hawaiian free-for-all!”. The return of Lono is a powerful demonstration of and metaphor for the resurgence of cultural practices, intersectional belonging, and the affirmation of Kānaka Maoli sexuality that each participant hoped to see on the horizon.

5.1. Talking Story

Talk-story is an approach to conversational storytelling that is an important aspect of local and Hawaiian culture (Kahakalau 2004; Kana‘iaupuni and Kawai‘ae‘a 2008; Kaomea 2004). The researcher believes that the theme can be felt and understood in the telling of the story (best when it is read aloud). With only minimal edits to the narratives, the researcher hopes to have presented these voices with integrity and respect.

“And I told her”“…You know, cuz family is important to me.I would have a really hard time.I thought they weren’t gonna accept mebecause my mom,especially my mom, is heavy into the Catholic church,like, she teaches Catholic school.So, I was like, for sure my mom is not gonna be okay with this.Because even when I was a senior in high school, and mom suspected I was gay—like, gay as in female/female—The way my mom approached me was like,“What, ‘chu gay?”You know, like, it was real aggressive…and I was just like—“Oh, no no, I not! I not!”And I just kept saying I’m not when I’m really, I reallyWas…and, I was like, “Oh, I can’t tell her…”So when I finally told her, I said—I always say, crying always works, becauseI just cried to her.And I told her.And she said, “Come home, we’ll talk about it.”And that’s when we talked about it. And I told her, that’s when I also told her that I thought she was going to, you know, not want anything to do with me because of the whole religion factor.And for a little while, my mom wouldn’t talk about it. Me.”(Alvarez 2016)

5.2. Presenting the Findings: Co-Performative Witnessing

Between February 2016 and November 2017, I presented seven performances of the script for 80 (unduplicated) people, including faculty members and doctoral students from several universities, community members and practitioners attending national conferences, and participants from the study. I collected dialogic feedback forms (Alvarez 2017) from more than one third of the participants, which I scanned and uploaded into Atlas. Ti for analysis. The worksheets asked the spect-actors to share the following: (1) sights, sounds, smells, images; (2) disruptions of the “master narrative”; (3) questions, challenges, appeals to the researcher; and, (4) a word, poem, or drawing reflecting on what they heard. In this manuscript, each co-performative witness is referred to as a spect-actor, from Boál’s Forum Theater, where he theorized that the theater can liberate the audience to think for themselves and to become actors in the revolution (Boal 1979).

Specifically, co-performative witnessing (Conquergood 1991, 2002; Madison 2006, 2007) is a space for active dialogue between audience members and researchers to reflect on themes, challenges, and implications for research and practice in the field. Co-performative witnessing means “a shared temporality, bodies on the line, soundscapes of power, dialogic interanimation, political action, and matters of the heart” (Madison 2007, p. 827). Co-performative witnessing begins in a borderland, a place of “tactical struggle” (Madison 2007, p. 827), and must be rooted in dialogue, speaking with, not of, others. It can be imagined as a transformational theorizing, a reflexive time and space to envision better, alternative futures. Researchers can engage in co-performative witnessing through deep engagement with the communities they are researching (Conquergood 1991), which shifts the power dynamics between researcher and researched and acknowledges the reciprocal impact each has on the other. Applying this model of active, participatory theater, I asked the spect-actors to “think with our story instead of about it” (my emphasis, Ellis and Bochner 2000, p. 735). There were great insights in the worksheets, as well as a fair amount of variation in the ways people responded to the performances. Below are two examples of completed dialogic performance worksheets, followed by an overview of the themes that emerged from the analysis.

Themes and examples from co-performative witnesses:

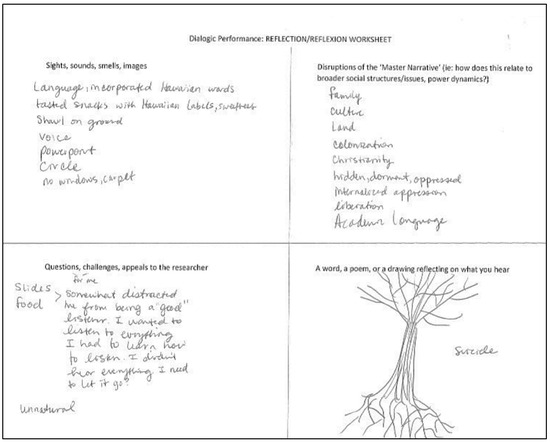

Example one, from an anonymous spect-actor, Atlanta, 2016 (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Dialogic Performance Worksheet from anonymous spect-actor, Atlanta, 2016.

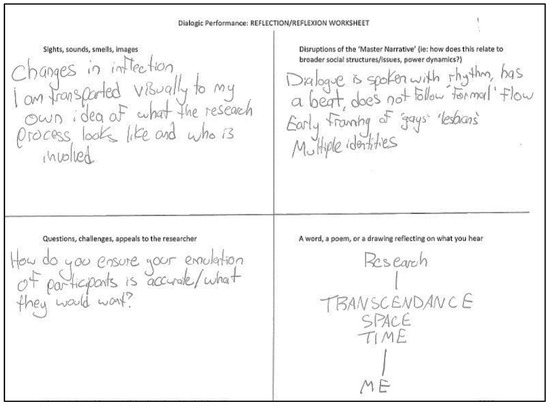

Example two, from an anonymous spect-actor, Toronto, 2017 (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Dialogic Performance Worksheet, anonymous spect-actor, Toronto, 2017.

Reflections about the performance process, approach. Several spect-actors described noticing and reflecting upon the multiple and simultaneous sources of information (live performer, PowerPoint slide with information, food to eat) and the ways it complicated (implicated?) the audience member as a listener. “Picturing the dialogue but at the same time seeing the images keeps me reflecting on Whiteness—and how I see the images keeps reminding me to come back to the dialogue,” anonymous spect-actor, Toronto, 2017. Several also describe responding to hearing Hawaiian words, different tones and types of voices, and the rhythm of the piece. “Words I don’t know, which come up often. A story about language,” anonymous spect-actor, Colorado, 2017. There was also a collective appreciation of the foregrounding of the participants (the “comrades”) and the minimal inclusion of the voice of the researcher herself. “I felt I was put in the context of the storyteller the moment the person was interviewed. Intense, emotional,” anonymous spect-actor, Toronto, 2017.

Identification with the context and content of the stories. A number of spect-actors voiced the resonance of the topic with their own or other marginalized and oppressed communities, particularly with high/disproportionate suicide rates. “Suicide: an exit from colonization, Lakota, too!” anonymous spect-actor, Louisiana, 2017. Several spect-actors described similar experiences with historical and colonial trauma as the stories that were shared. Along with a drawing of a broken heart was the writing, “Like barbed wire it cuts through me. I walk around tears and blood dripping from me. Colonization leaves scars, wounds, and pains. Sometimes they are there, sometimes they are not. Sometimes they come up, surface… re-surface from somewhere deep down,” anonymous spect-actor, Colorado, 2017. “Performance centers the narrative on decolonization. Gives it power!” anonymous spect-actor, Louisiana, 2017.

Questions and reflections for further exploration. Some spect-actors shared reflections on the ways that Christianity (and possibly religion in general) has contributed to the colonization and marginalization of Indigenous and LGBTQM communities. “Church as oppression —> colonization of LGBTQM?” anonymous spect-actor, Atlanta, 2016. Others discussed the ways that colonization becomes normalized and accepted as part of a community’s day-to-day functions. “How colonization is embodied, collective, and mapped onto daily life” anonymous spect-actor, Toronto, 2017. Several expressed the validity of the methods for the communities and populations in the study and of the experience that is co-created by the sharing of the stories through performance. “This methodology allows people of color, Indigenous people, and marginalized and oppressed people to experience and share their truth; to reconnect to their roots; and for the others to participate in the shared truth” anonymous spect-actor, Colorado, 2017.

Calls to action, resistance, and towards liberation. One spect-actor shared a poem about their own experience living in Hawaii, describing being called a racial slur that at the time they experienced as painful but that they now see as a motivation to act:

“Aloha ha`ole.My experiences living in Hawaiithese words burned at firstNow I understandI grew to understandI had to understandThey had to burnthe fire is fuel—fuel to advocate for,fuel to live and work for—liberation.”Anonymous spect-actor, Colorado, 2017.

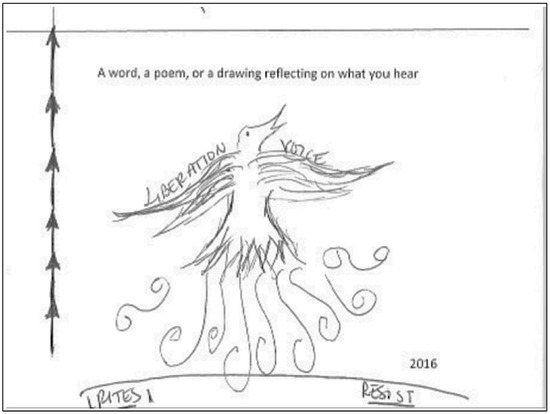

Another spect-actor created a drawing (see Figure 3) of a bird rising with the words “rites” and “resist” beneath it, and the words “liberation” and “voice” written above its wings:

Figure 3.

Close up of a Dialogic Reflection Worksheet, anonymous spect-actor, Louisiana, 2017.

Table 1 includes a summary of each set of findings, first outlining the findings from the initial research and then from the performance project.

Table 1.

Findings from research and performance projects.

6. Discussion: Performance as a Queer, Decolonial Process?

This project locates queer, Native Hawaiian identities in the Fourth World context of Hawaii. The impacts of colonization at the intersections of racial/ethnic and sexual/gender identities are described through stories of family support or rejection, religiosity, and enculturation through (re)claiming Native Hawaiian cultural practices. The voices of the participants are in the foreground of both analysis and reporting, and the positionality and insider/outsider status of the researcher are described and debriefed. This is both a phenomenological and a performative inquiry and contributes both content and process to the field.

Conquergood (2013) describes performance as an epistemology (yes!), as well as a tactic, but is performance specifically/also a queer, Indigenous intervention? Does performance have the potential to change, challenge, and produce healing? Does queer Indigeneity need performance?

Alexander describes the many overlaps between queer and postcolonial theories and argues that “each moves toward illuminating and dismantling systems of oppression by engaging critical analysis of those systems” (Alexander 2008, p. 105), and he also argues that each movement is centered in Whiteness. Even the “post-” in postcolonial theory erases the current and ongoing impacts of colonization impacting Indigenous communities today (Smith 1999). Many queer critical scholars of color offer powerful critiques about the lack of attention to the ways that colonization, heterosexism, and trans/homophobia work together to create and uphold imperialist structures of oppression and marginalization around the globe (Alexander 2008; Duggan 2002; Johnson and Henderson 2005; Puar 2007). Alexander pushes against a postcolonial perspective that does not leave room for queerness, and a queer theory that creates homogenous subjects of the State. Similarly, Swadener and Mutua (2008) describe the need for more performance and more collaboration in Indigenous research: “we anticipate more hybrid identities and border-crossers performing research in ways that resist “insider–outsider” dichotomies while continuing to foreground Indigenous issues and work” (p. 41). Adams and Holman Jones (2008) argue that queer projects are border-crossing and inherently disrupt oppressive systems and push for change. Adams and Holman Jones (2008) search for the hope, promise, and possibility queer stories can provide. The Alvarez et al. (2024) charges us to think about the unique needs of queer, Asian, and Pasifika peoples in particular, and what queerness and Indigeneity look like through the lenses of migration, immigration, and layers of colonization. Through the sharing of queer, Indigenous stories, can communities and individuals approach healing? Collaboration? Resilience? Can queer performances of Indigenous voices help us to resist the normalization of categorization and create new possibilities for activism along intersectional lines?

Based on Conquergood’s (1985) guidelines for performing as a moral act, Hamera suggests an ethic for the interdisciplinary utilization of performance, which includes paying homage to the intellectual lineage of the work and of the conditions and connections that are creating the work (Hamera 2013). In Madison (2012), De Le Garza puts forward an “ethics of postcolonial ethnography” that demands accountability, context, truthfulness, and community (Madison 2012, pp. 112–13). Through embodiment rather than textuality, clear directives for relational accountability, and a focus on subjugated knowledge, performance has the potential to act as a decolonial practice, pedagogy, and process.

Decolonization is a process and theoretical approach to research, as well as an act of valuing and centering Indigenous ways of speaking and knowing (Swadener and Mutua 2008). Swadener and Mutua (2008) discuss theories of performance and their application in decolonial research projects and suggest that performative approaches to decolonial research are acts of resistance to positivist, neoliberal, Western paradigms. These methods often have activist agendas, to work towards self-determination, liberation, and social justice. Kovach (2009) describes G. Smith’s (1997) observations that a decolonial approach analyzes and addresses power, offers hope for change, creates space for both personal and structural change within the sites of resistance, and celebrates small gains. In similar ways, performance methodologies can utilize an actively decolonial lens in the ways that the performances interrogate imperialism and colonial power structures, provide utopian visions for transformation and liberation from oppression and marginalization, and embody the feminist praxis of resistance in both personal and structural locations. Kovach (2009) argues that “a decolonizing agenda must be incorporated within contemporary explorations of Indigenous inquiry because of the persisting colonial influence on Indigenous representation and voice in research” (p. 81). Beltran and colleagues suggest that ceremony can be an integral part of community-based and participatory research approaches with Indigenous community members (Beltrán et al. 2024).

In Hawaii, a site of historical and ongoing colonial occupation, the necessity of research frameworks that re-center the voices of Native Hawaiians and the application of research methodologies that address the power imbalances within the research process cannot be overstated. Through story and performance methods, and in ways that are “determined and defined from within the community” (Denzin et al. 2008, p. 6), it is my intention to work alongside the Native Hawaiian community to support strategies for healing and resisting the traumas they continue to endure. Additionally, through relationships with community leaders and Indigenous practitioners, my approach to this research aligns with the ethic that Kovach describes as “giving back to the community in a way that is useful to them” (Kovach 2009, p. 82).

Limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of performance methodologies in suicide prevention research in Indigenous communities, and many are rooted in the benefits described thus far. De La Garza’s guidelines of relational accountability, context, truthfulness, and community (Madison 2012) can serve as reminders of the potential slipperiness of performance methodologies. For example, are the performance outcomes representative of the co-creators of the knowledge, and have the findings been shared with or returned to the sources of the content? Have the findings been taken out of context or uprooted from their original place? Are they vague or disconnected from their source? The expansiveness and visioning that may grow from a performance approach could also pull the content far from the truth and context of the initial exploration.

Efforts to mitigate these limitations should include active work on the relationships and collaboration that produced the knowledge. There are, however, concerns in this process as well. Community members who contribute to research using performance methodologies might feel limited in their abilities to address bias or misconceptions in the research if power and collaboration are not attended to. There could be concepts rooted in Indigenous ontologies or epistemologies that are inaccurately represented or understood. For researchers working in Indigenous communities, honoring the Indigenous knowledge that is informing how the community is engaging in the processes and acknowledging the particular place-based elements of the work are critical to the success of the project.

7. Implications

Pollock (2006) asks what performance has done for ethnography and puts forward the four following contributions. He suggests that performance redefines how cultural spaces are viewed and researched; that it transforms the roles of researcher and researched; that it enhances the representation of findings and shifts to the embodiment of storytelling; and that it emphasizes theories of the flesh (Pollock 2006). Can we not apply the same learnings for what performance can give to social work research and, specifically, to suicide prevention research?

For social work research and suicide prevention research, performance can change the location of the research site from a physical location to a specific embodied intersection—for example, queer and Native Hawaiian identity. Performance can alter the roles of the researcher and the researched, through the reflexivity and transparency of performative writing; through the vulnerability of the performance the researcher becomes the one who is observed, judged, and analyzed. Performance can help social work research findings become active, embodied interventions, perhaps even allowing new solutions to be practiced and envisioned. Additionally, performance can center the voices and lived experiences of marginalized bodies through poetic transcription and the embodiment of a performative text.

In a compelling discussion of narrative medicine, Langellier describes storytelling, hearing, ordering, and naming as fundamental elements of medicine and the roles of doctor and patient (Langellier 2009). She underlines the power and potential resistance that exist in a person’s narrative of health or illness, and the performative elements of sharing and receiving these stories. Further, Langellier acknowledges that the life of the patient depends upon the readability of their story and the capacity of the practitioner to perform a close and imaginative read. How can we appropriately employ “stereophonic listening, the ability to hear the body and the person who inhabits it” (Charon 2006, p. 97)? Informed by performance theories, pedagogies, and practices, and with the understanding that our client’s lives depend upon it, can social workers strengthen our capacity for listening and develop our ability to story-ask?

Methods and Critical Suicidology. Critical Suicidology argues that there is a need for qualitative research on suicide to produce knowledge that is new and that is practical, creative, and person-centered, and also that qualitative methods have to be rigorous and scientific (Hjelmeland 2016). The analytic methods must be included in qualitative reporting, and data must be rigorously analyzed. Qualitative research must consider the sociocultural context and, specifically, how that context affects what we know of risks and protections (Hjelmeland 2016). Further, some Critical Suicidologists argue that suicide cannot be entirely contained by language and should be explored through poetry and resonance rather than through causality (Jaworski and Scott 2016). Jaworski and Scott (2016), for example, analyze three poems to examine how poetry contributes to our understanding of suicide and the ways that resonance (especially emotional resonance) can contribute to that understanding. They argue that poetry is a response towards others that can help us be thoughtful in how we approach grieving and, in particular, how we understand the finality of suicide (Jaworski and Scott 2016). Narrative practices, too, have shed light on the politics and socio-historical elements of suicide, including the impacts of colonization on Indigenous life and death; the ways that language is used with and around suicide; and how to tell the end of someone’s story (Sather and Newman 2016). Critical Suicidologists argue that narrative allows for diversity in language, nuance, and a simultaneous collectivizing of experience through a recognition of similar emotional responses (Sather and Newman 2016). For example, Sather and Newman gathered stories from therapists and community practitioners in New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Nigeria, Canada, and the U.S. about how the people they are working with (and themselves) make sense of suicide, share the news of suicide, and work with survivors of suicide loss, as well as how communities have dealt with the loss, and what cultural and social considerations have been made (Sather and Newman 2016). The goal of sharing the stories is to create and document the skills and knowledge that have been developed by people surviving suicide losses, and that offer generative approaches to honoring and remembering those who have been lost (Sather and Newman 2016).

Practice/clinical implications. There is a growing body of research arguing for multi-layered, culturally relevant, community-based responses to suicide prevention in Indigenous communities (Goebert et al. 2018; Hjelmeland 2016; Kral and White 2017; Kral and Idlout 2016; Middlebrook et al. 2001). This study begins to address the calls for innovation, indigenization, and research rooted in the voices of the communities themselves (Goebert et al. 2018; Trinidad 2009), and it can lead to important changes in suicide prevention and intervention in clinical and community-based practice.

8. Conclusions

As a method of inquiry, transcription, and reporting, performance methodologies offer a rich and complicated portrait of social work research, research participants, and the researchers ourselves. Interrogating the boundaries between the observer and those observed, elements of performance methodologies take the qualitative researcher beyond analytic memos and bracketing. Performative methods center reflexive processes as integral to the research. Direct questions and dialogic rituals evoke critical intersectional feminism and invite the readers to begin imagining themselves as co-witnesses of the space, co-creators of the knowledge (Beltrán et al. 2024).

Critical queer Indigenous scholars argue that the interrogation of heteropatriarchy and heteronormativity from an Indigenous lens must be part of the decolonization project (Beltrán et al. 2020; Finley 2011). This project emphasizes that suicide research in the Native Hawaiian community—and in LGBTQM Native Hawaiian communities, in particular—must be actively decolonial. Decolonial suicide prevention research needs to go beyond an Indigenous model of prevention that neither accounts for nor interrogates the oppressive hetero-, homo-, and cis-normative mechanisms within the community that may be causing additional harm (Alvarez et al. 2020). Decolonial research on Native Hawaiian suicide must be grounded in social justice and cultural knowledge. Researchers must do more than reject the dominant understandings of suicide risk by seeking alternative ways of understanding to prevent these deaths.

CLOSING:

These stories do not have endings. They are conjectures—incomplete without dialogue, reciprocity, and further actions against the master narrative(s).

Limitations abound: what has been lost in translation? What did I fail to ask in the first place? Do the words colonization and suicide even begin to represent the experiences of the overthrow, the commodification, the daily struggles and acute violence that people face in Hawaii?

How can I tell these stories with relevance and meaning so many thousands of miles away? What impact can I have? Who will hold me accountable?

Today, I hope, it will be you, and that the sharing of these words will push or pull or provoke a response. Whatever the case, I am grateful to have heard and seen and spoken these truths, and I am motivated to continue moving towards liberation.(Alvarez 2016)

Funding

This research was funded by the Walter F. LaMendola Pre-Doctoral Assistantship, University of Denver Graduate School of Social Work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Denver (protocol 816085-1, 2015) on 5 November 2015.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Additional data are not publicly available. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the community members, “spect-actors,” friends, and colleagues who supported this project over the years. In particular, I would like to honor the many kānaka maoli who shared their stories with me, invited me to learn and listen to Indigenous protocols and practices, and who urged me to continue doing this research: mahalo and salamat.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Note

| 1 | Māhū is a Native Hawaiian word describing an individual possessing both male and female characteristics (Pukui et al. 1972). |

References

- Adams, Tony E., and Stacy Holman Jones. 2008. Autoethnography is queer. In Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 373–90. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Bryant Keith. 2008. Queer(y)ing the postcolonial through the west(ern). In The SAGE Handbook of Critical Indigenous Methodologies. Edited by Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln and Linda Tuhiwai Smith. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 101–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Antonia R. G. 2016. Risks, Rites and Resistance: (Re)performing Queerness in the Fourth World. Script for performances between March-October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Antonia R. G. 2017. Performance pedagogies in suicide prevention research: (Re)presenting queerness in Indigenous communities. Paper presented at the 21st Annual Conference of the Society for Social Work and Research (SSWR), New Orleans, LA, USA, January 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Antonia R. G., Val. Kalei Kanuha, Maxine K.L. Anderson, Cathy Kapua, and Kris Bifulco. 2020. “We Were Queens.” Listening to Kānaka Maoli Perspectives on Historical and On-Going Losses in Hawai’i. Genealogy 4: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Antonia R. G., Gita R. Mehrotra, Sameena Azhar, Anne S. J. Farina, and Alma M. Ouanesisouk Trinidad. 2024. Exploring the Radical Potential of Queer AZN and Pasifika CRT for Clinical Social Work Praxis. Studies in Clinical Social Work: Transforming Practice, Education and Research 94: 273–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, Ramona, Antonia Alvarez, and Miriam Puga-Madrid. 2020. Morning star, sun, and moon share the sky: (Re)membering Two-Spirit identity through culture-centered HIV prevention curriculum for Indigenous youth. In Good Relation: History, Gender, and Kinship in Indigenous Feminisms. Edited by Sarah Nickel and Amanda Fehr. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-851-1. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Ramona, Antonia R. G. Alvarez, My Noc To, Annie Zean Dunbar, Blanca Azucena Pacheco, and Miriam Valdovinos. 2024. “I hope this brings comfort to others; it’s brought me comfort too”: Ceremony-based participatory practice research as Indigenist feminist methodology. In Affilia: Feminist Inquiry in Social Work. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boal, Augusto. 1979. Theatre of the Oppressed. Translated by Charles A. McBride. New York: Theatre Communications Groups. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, Heather. 1999. Pacific Island suicide in comparative perspective. Journal of Biosocial Science 31: 433–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Angela, Catherine W. Barber, Deborah M. Stone, and Aleta L. Meyer. 2005. Public health training on the prevention of youth violence and suicide: An overview. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 29: 233–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrage, Rachel L., Joseph P. Gone, and Sandra L. Momper. 2016. Urban American Indian community perspectives on resources and challenges for youth suicide prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology 58: 136–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, Rita. 2006. Narrative Medicine Honoring the Stories of Illness. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conquergood, Dwight. 1985. Performing as a moral act: Ethical dimensions of the ethnography of performance. Literature in Performance: A Journal of Literary and Performing Art 5: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conquergood, Dwight. 1991. Rethinking ethnography: Towards a critical cultural politics. Communications Monographs 58: 179–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conquergood, Dwight. 2002. Performance studies: Interventions and radical research. The Drama Review 46: 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conquergood, Dwight. 2013. Cultural Struggles: Performance, Ethnography, Praxis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K. 2003. Performance Ethnography Critical Pedagogy and the Politics of Culture. Thousand Oaks and London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K. 2006. Pedagogy, performance, and autoethnography. Text and Performance Quarterly 26: 333–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, Norman K., Yvonna S. Lincoln, and Linda Tuiwai Smith. 2008. Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Lisa. 2002. The new homonormativity: The sexual politics of neoliberalism. In Materializing Democracy. Edited by D. D. Nelson. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, Eduardo. 2006. Healing the Soul Wound: Counseling with American Indians and Other Native Peoples. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn, and Art P. Bochner. 2000. Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 733–68. [Google Scholar]

- Else, Iwalani R. N., and Naleen N. Andrade. 2008. Suicide among Indigenous Pacific Islanders in the U.S.: A historical perspective. In Suicide Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Frederick T. Leong and Mark M. Leach. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 143–17. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, Chris. 2011. Decolonizing the queer Native body (and recovering the Native bull- dyke): Bringing “sexy-back” and out of a Native studies’ closet. In Queer Indigenous Studies: Critical Interventions in Theory, Politics, and Literature. Edited by Qwo-Li Driskill, Chris Finley, Brian Joseph Gilley and Scott Lauria Morgensen. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Galanis, Dan, and Art Tani. 2019. Addressing suicide prevention in Hawaii. Paper presented at the Tools for Suicide Prevention and Intervention: Hope, Help & Healing, Honolulu, HI, USA, April 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goebert, Deb, Antonia R. G. Alvarez, Naleen N. Andrade, JoAnne Balberde-Kamalii, Barry S. Carlton, Shaylin Chock, Jane J. Chung-Do, M. Diane Eckert, Kealoha Hooper, Kaohuonapua Kaninau-Santos, and et al. 2018. Hope, help, and healing: Culturally embedded approaches to suicide prevention, intervention and postvention services with Native Hawaiian youth. Psychological Services 15: 332–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamera, Judith. 2013. How to do things with performance (again and again …). Text and Performance Quarterly 33: 202–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, Simon. 2016. Indigenous Suicide: A global perspective with a New Zealand focus. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 61: 684–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawaii State Department of Health. 2012. Hawaii Injury Prevention Plan 2012–2017. Available online: https://health.hawaii.gov/injuryprevention/files/2013/09/Hawaii_Injury_Prevention_Plan_2012_to_2017_4mb.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Hjelmeland, Heidi. 2016. A critical look at current suicide research. In Critical Suicidology: Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Edited by Jennifer White, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral and Jonathan Morris. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Holman Jones, S. 2005. Autoethnography: Making the personal political. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 763–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Ernest, and Desley Harvey. 2002. Indigenous suicide in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Emergency Medicine Australasia 14: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, Katrina, and Daniel G. Scott. 2016. Understanding the unfathomable in suicide: Poetry, absence, and the corporeal body. In Critical Suicidology: Transforming Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Edited by Jennifer White, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral and Jonathan Morris. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 209–28. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E. Patrick, and Mae G. E. Henderson. 2005. Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kahakalau, Kū. 2004. Indigenous heuristic action research: Bridging Western and Indigenous research methodologies. Hûlili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being 1: 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kana‘iaupuni, Shawn Malia, and Keiki K. C. Kawai‘ae‘a. 2008. E Lauhoe Mai Na Wa‘a: Toward a Hawaiian Indigenous education teaching framework. Hulili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being 5: 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kaomea, Julie. 2004. Dilemmas of an Indigenous academic: A Native Hawaiian Story. In Decolonizing Research in Cross-Cultural Contexts. Edited by Kagendo Mutua and Beth Blue Swadener. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, Margaret. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kral, Michael J. 2012. Postcolonial suicide among Inuit in Arctic Canada. Journal of Culture Medicine and Psychiatry 36: 306–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kral, Michael, and Jennifer White. 2017. Moving toward a critical suicidology. Annals of Psychiatry and Mental Health 5: 1099–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, Michael J., and Lori Idlout. 2016. Indigenous best practices: Community-based suicide prevention in Nunavut, Canada. In Critical Suicidology: Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Edited by Jennifer White, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral and Jonathan Morris. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langellier, Kristin M. 2009. Performing narrative medicine. Journal of Applied Communication Research 37: 151–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, David M., and Christian K. Alameda. 2011. Social determinants of health for Native Hawaiian children and adolescents. Hawaii Medical Journal 70: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Madison, D. Soyini. 2005. Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Madison, D. Soyini. 2006. The Dialogic Performative in Critical Ethnography. Text and Performance Quarterly 26: 320–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, D. Soyini. 2007. Co-performative witnessing. Cultural Studies 21: 826–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, D. Soyini. 2012. Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrook, Denise L., Pamela L. LeMaster, Janette Beals, Douglas K. Novins, and Spero M. Manson. 2001. Suicide Prevention in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities: A Critical Review of Programs. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 31: 132–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Day, Michelle. 2008. Performance matters. Qualitative Inquiry 14: 1458–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Della. 2006. Marking New Directions in Performance Ethnography. Text and Performance Quarterly 26: 325–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puar, Jasbir K. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pukui, Mary Kawena, E. W. Haertig, and Catherine A. Lee. 1972. Nānā i ke kumu: Look to the Source. Honolulu: Hui Hanai, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Sather, Marnie, and David Newman. 2016. “Being more than just your final act”: Elevating the multiple storylines of suicide with narrative practices. In Critical Suicidology: Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Edited by Jennifer White, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral and Jonathan Morris. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press, pp. 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shimei, Nur, Michal Krumer-Nevo, Yuval Saar-Heiman, Sivan Russo-Carmel, Ilana Mirmovitch, and Liora Zaitoun-Aricha. 2016. Critical social work: A performance ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry 22: 615–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Carrol A. M., and Agatha M. Gallo. 2007. Applications of performance ethnography in nursing. Qualitative Health Research 17: 521–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York: Zed Books, Ltd., vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stoor, Jon Peter, Niclas Kaiser, Lars Jacobsson, Ellinor Salander Renberg, and Anne Silviken. 2015. “We are like lemmings”: Making sense of the cultural meaning(s) of suicide among the indigenous Sami in Sweden. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 74: 27669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swadener, Beth Blue, and Kagendo Mutua. 2008. Decolonizing performances: Deconstructing the global postcolonial. In Handbook of Critical Indigenous Methodologies. Edited by Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln and Linda Tuhiwai Smith. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad, Alma M. Ouanesisouk. 2009. Toward kuleana (responsibility): A case study of a contextually grounded intervention for Native Hawaiian youth and young adults. Aggression and Violent Behavior 14: 488–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, Lisa. 2009. The Importance of Identity, History, and Culture in the Wellbeing of Indigenous Youth. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 2: 267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, Lisa M., and Joseph P. Gone. 2016. Exploring possibilities for Indigenous suicide prevention. In Critical Suicidology: Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Edited by Jennifer White, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral and Jonathan Morris. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- White, Jennifer. 2007. Working in the midst of ideological and cultural differences: Critically reflecting on youth suicide prevention in Indigenous communities. Canadian Journal of Counseling 41: 213–27. [Google Scholar]

- White, Jennifer. 2015. Shaking up suicidology. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 4: 1–4. Available online: http://wp.me/p1Bfg0-26q (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- White, Jennifer. 2017. What can critical suicidology do? Death Studies 41: 472–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Jennifer, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral, and Jonathan Morris, eds. 2016. Critical Suicidology: Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).