Effectiveness of School Violence Prevention Programs in Elementary Schools in the United States: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

- (1)

- What types of elementary school violence prevention programs have been implemented in the United States?

- (2)

- Are elementary school programs effective in reducing the occurrence of school violence among children aged 5–12 years?

- (3)

- What types of tools have been utilized to enhance these programs?

3.2. Search Methods

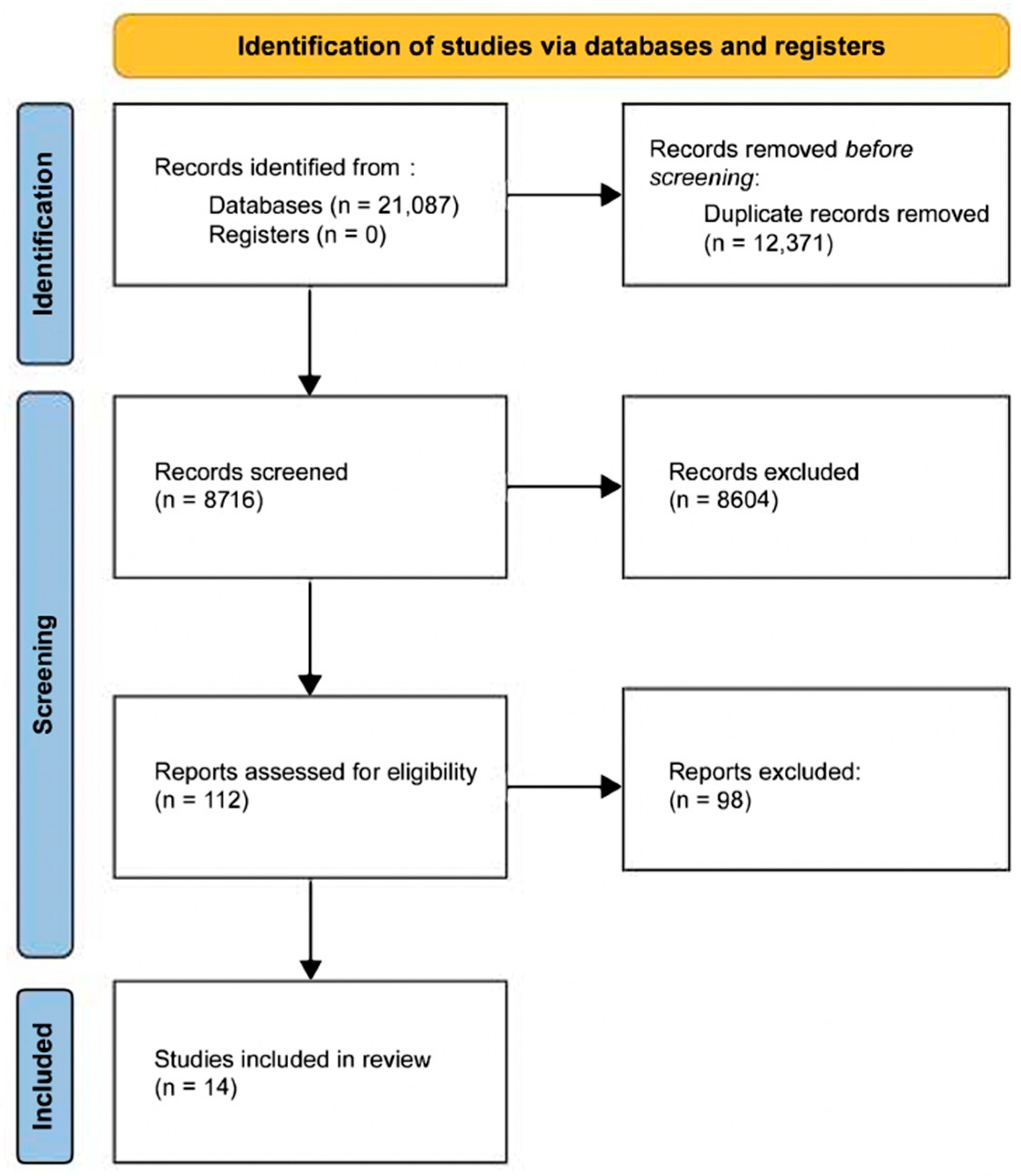

3.3. Review Process

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. School Violence Prevention Programs

4.2. Effectiveness of School Violence Prevention Programs

4.3. Tools to Reduce School Violence

5. Discussion

5.1. Program Strategy

5.2. Reduction in Negative Behaviors

5.3. Tool Agents

5.4. Behavioral Expectations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Impact Statement

References

- Abbott, Anastasia. 2021. Teacher Emotions and Perspectives on Implementation of Social-Emotional Curricula. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Johnie J., and Craig A. Anderson. 2017. Aggression and Violence: Definitions and Distinctions. In The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra Leite de Souza, Jacyara Adrielle, Adriana Conrado de Almeida, Rhayssa Oliveira Lopes de Sá, Manuela Campos Maia, Murilo Henrique Bezerra Leite de Souza, and Betise Mery Alencar Sousa Macau Furtado. 2021. Characteristics of aggressors and victims of bullying in studying in a public elementary school and high school. Journal of Research and Development 11: 51664–69. [Google Scholar]

- Boulter, Lyn. 2004. Family-school connection and school violence prevention. Negro Educational Review 55: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Catherine P., Sarah Lindstrom Johnson, Yifan Zhu, and Elise T. Pas. 2020. Scaling up behavioral health promotion efforts in Maryland: The economic benefit of positive behavioral interventions and supports. School Psychology Review 50: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Catherine P., Tracy E. Waasdorp, and Philip J. Leaf. 2012. Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Pediatrics 130: e1136–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunson, Brittany Nicole. 2023. Effectiveness of Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports on School Climate and Teacher Perceptions at Title I Elementary Schools in the Southeastern Region of the United States. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Raquel M. 2022. Understanding the Implementation, Benefit, and Feasibility of SWPBIS in the Classroom Environment. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Morata, Antonio, Cristina Alonso-Fernández, Manuel Freire, Iván Martínez-Ortiz, and Baltasar Fernández-Manjón. 2020. Serious games to prevent and detect bullying and cyberbullying: A systematic serious games and literature review. Computers and Education 157: 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofferson, Remi Dabney, and Kathe Callahan. 2015. Positive behavior support in schools (PBSIS): An administrative perspective on the implementation of a comprehensive school-wide intervention in an urban charter school. Education Leadership Review of Doctoral Research 2: 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- CNN. 2019. Columbine High School Shootings Fast Facts. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2013/09/18/us/columbine-high-school-shootings-fast-facts/index.html (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Corbin, Catherine M., Maria L. Hugh, Mark G. Ehrhart, Jill Locke, Chayna Davis, Eric C. Brown, Clayton R. Cook, and Aaron R. Lyon. 2022. Teacher perceptions of implementation climate related to feasibility of implementing schoolwide positive behavior supports and interventions. School Mental Health 14: 1057–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Dewey, Jennifer L. Maeng, Anna Grace Burnette, Yuane Jia, Francis Huang, Timothy Konold, Pooja Datta, Marisa Malone, and Patrick Meyer. 2018. Student threat assessment as a standard school safety practice: Results from a statewide implementation study. School Psychology Quarterly 33: 213–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, Kristin. 2022. Document Analysis of Behavior Expectations and Disciplinary Action Policies of Public Preschools in Maine. Honors Thesis, University of Maine. DigitalCommons@UMaine. Available online: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/731/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Department of Justice. 2020. Press Release. Office of Public Affairs. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Duncan, Robert, Isaac J. Washburn, Kendra M. Lewis, Niloofar Bavarian, David L. DuBois, Alan C. Acock, Samuel Vuchinich, and Brian R. Flay. 2017. Can universal SEL programs benefit universally? Effects of the positive action program on multiple trajectories of social-emotional and misconduct behaviors. Prevention Science 18: 214–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, Marta, Diego Monferrer, Alma Rodríguez, and Miguel Ángel Moliner. 2021. Does emotional intelligence influence academic performance? The role of compassion and engagement in education for sustainable development. Sustainability 13: 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelio, Carlos, Pablo Rodríguez-González, Javier Fernández-Río, and Sixto Gonzalez-Villora. 2022. Cyberbullying in elementary and middle school students: A systematic review. Computers and Education 176: 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fite, Paula J., Elizabeth C. Tampke, and Rebecca L. Griffith. 2023. Defining Aggression: Form and Function. In Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology. Edited by Johnny L. Matson. Autism and Child Psychopathology Series; Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flay, Brian R. 2014. Replication of effects of the “positive action” program in randomized trials in Hawai’i and Chicago schools. Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, Michael, and Gale Morrison. 2000. The school in school violence: Definitions and facts. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 8: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, Hannah, Maria M. Ttofi, and David P. Farrington. 2021. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying perpetration and victimization: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 17: e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, Nicholas A., Lydia Beahm, Rachel Kaplan, Ashley S. MacSuga-Gage, and Ahhyun Lee. 2020. Using positive behavioral interventions and supports to reduce school suspensions. Beyond Behavior 29: 132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Jennifer E., Paul D. Flaspohler, and Vanessa Watts. 2015. Engaging youth in bullying prevention through community-based participatory research. Family and Community Health 38: 120–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, Samantha E., Jamie B. Finn, and Melissa J. Leslie. 2022. Classroom management and remote teaching: Tools for defining and teaching expectations. Teaching Exceptional Children 54: 404–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greflund, Sara, Kent McIntosh, Sterett H. Mercer, and Seth L. May. 2014. Examining disproportionality in school discipline for aboriginal students in schools implementing PBIS. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 29: 213–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandson, Kim. 2019. Trends in Social-Emotional Learning Research: What Are the Outcomes? Available online: https://www.cfchildren.org/blog/2019/06/trends-in-social-emotional-learning-research-what-are-the-outcomes/ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Hannigan, Jessica Djabrayan, and John Hannigan. 2020. Best practice PBIS implementation. Journal of School Administration Research and Development 5: 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Jennifer. 2022. Here’s How to Help Those Affected by the Uvlade School Shooting. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/05/25/help-uvalde-texas-shooting-victims/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Holt, Amanda. 2017. Parricides, School Shootings and Child Soldiers: Constructing criminological phenomena in the context of children who kill. In Different Childhoods: Non/Normative Development and Transgressive Trajectories. London: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 132–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Zaheer, Kagan Kircaburun, Mustafa Savcı, and Mark D. Griffiths. 2023. The role of aggression in the association of cyberbullying victimization with cyberbullying perpetration and problematic social media use among adolescents. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, Véronique, Ke Wang, Jiashan Cui, and Alexandra Thompson. 2023. Indicators of School Crime and Safety. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/report-indicators-school-crime-and-safety-2022-and-indicator-2-incidence#0-0 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Katersky, Aaron, and Susanna Kim. 2014. Five Disturbing Things We Learned Today about Sandy Hook Shooter Adam Lanza. Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/US/disturbing-things-learned-today-sandy-hook-shooter-adam/story?id=27087140 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Kennedy, Kewanis. 2021. School Violence and Its Impact on Student Academic Achievement. Available online: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1249&context=etd (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Kranz, Michal, Lauren Frias, and Azmi Haroun. 2018. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/who-were-the-victims-of-the-sandy-hook-shooting-2017-12 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- LaBelle, Brittany. 2023. Positive outcomes of a social-emotional learning program to promote student resiliency and address mental health. Contemporary School Psychology 27: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Ahhyun, and Nicholas A. Gage. 2020. Updating and expanding systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effects of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports. Psychology in the Schools 57: 783–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Kendra M., Stefanie D. Holloway, Niloofar Bavarian, Naida Silverthorn, David L. DuBois, Brian R. Flay, and Carl F. Siebert. 2021. Effects of positive action in elementary school on student behavioral and social-emotional outcomes. Elementary School Journal 121: 635–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Willone, Bee Theng Lau, and Fakir M. 2023. Cyberbullying awareness intervention in digital and non-digital environment for youth: Current knowledge. Education and Information Technologies 28: 6869–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C. 2018. Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports: A Study of Implementation at the Elementary Level in a Low-Income District. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Matthay, Ellicott C., and M. Maria Glymour. 2020. A graphical catalog of threats to validity. Epidemiology 31: 376–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClure, Heather H., J. Mark Eddy, Charles R. Martinez, Jr., Rubeena Esmail, Ana Lucila Figueroa, and Ruby Batz. 2022. Addressing US youth violence and Central American migration through fortifying children, families, and educators in Central America: A collaborative approach to the development and testing of a youth violence preventive intervention. In The Changing Tide of Immigration and Emigration During the Last Three Centuries. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, Terrence, and Marina Dias. 2023. American shooters inspire teen shooters abroad. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/04/12/brazil-school-shootings-columbine-effect/ (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- McDaniel, Sara C., Rhonda N. T. Nese, Sara Tomek, and Shan Jiang. 2022. District-wide outcomes from a bullying prevention programming. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 66: 276–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, Emily Amiah. 2018. Behavioral and Academic Outcomes Following Implementation of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention in an Urban Public School. Unpublished Master’s thesis, The University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meter, Diana J., Kevin J. Butler, and Tyler L. Renshaw. 2023. The buffering effect of perceptions of teacher and student defending on the impact of peer victimization on student subjective wellbeing. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Thomas W. 2023. School-related violence: Definition, scope, and prevention goals. In School Violence and Primary Prevention. Edited by Thomas W. Miller. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, Lauren E., Julia E. Moore, Jessica Trail, John James Van Epps, and Suellen Hopfer. 2013. Understanding real-world implementation quality and “active ingredients” of PBIS. Prevention Science 14: 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosechkin, Ilya, and Vladimar Krukovskiy. 2019. Victimiological Measures for Preventing School Shootings: Expert View. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences 14: 256–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Matt. 2022. Texas Shooting: How a Sunny Uvalde School Day Ended in Bloodshed. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-61577777 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Onion, Amanda, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen, and Christian Zapata. 2019. Columbine Shooting. Available online: https://www.history.com/topics/1990s/columbine-high-school-shootings (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Ostrov, Jamie M., Sarah J. Blakely-McClure, Kristin J. Perry, and Kimberly E. Kamper-DeMarco. 2018. Definitions—The form and function of relational aggression. In The Development of Relational Aggression. Edited by Sarah M. Coyne and Jamie M. Ostrov. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery 88: 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagones, Stephanie, Bill Melugin, Louis Casiano, and Ashlyn Messier. 2022. Who Is the Texas Shooter? What We Know. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/us/texas-school-shooter-what-we-know (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Pas, Elise T., Ji Hoon Ryoo, Rashelle J. Musci, and Catherine P. Bradshaw. 2019. A state-wide quasi-experimental effectiveness study of the scale-up of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Journal of School Psychology 73: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrasek, Michael, Anthony James, Amity Noltemeyer, Jennifer Green, and Katelyn Palmer. 2022. Enhancing motivation and engagement within a PBIS framework. Improving Schools 25: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picheta, Rob, Josh Pennington, Radina Gigova, and Amy Croffey. 2023. Serbia in Shock after School Shooting Leaves Eight Children and a Security Guard Dead. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/03/europe/serbia-school-shooting-intl/index.html (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Polanin, Joshua R., Dorothy L. Espelage, Jennifer K. Grotpeter, Katherine Ingram, Laura Michaelson, Elizabeth Spinney, Alberto Valido, America El Sheikh, Cagil Torgal, and Luz Robinson. 2022. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to decrease cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Prevention Science 23: 439–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, Gabriela, and Thomas Hughes. 2020. Could more holistic policy addressing classroom discipline help mitigate teacher attrition? EJournal of Education Policy 21: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, Priya, and Rakesh Aggarwal. 2020. Study designs—Part 7 systematic reviews. Perspectives in Clinical Research 11: 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, Jared R., and Sarah A. Stoddard. 2019. A critical review of anti-bullying programs in North American elementary schools. Journal of School Health 89: 759–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsmith-Jones, Kelley, James F. Anderson, and Adam H. Langsam. 2015. Expanding the Practice of Newsmaking Criminology to Enlist Criminologists, Criminal Justicians, and Social Workers in Shaping Discussions of School Violence: A Review of School Shootings from 1992–2013. International Journal of Social Science Studies 3: 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, Alisha Rahaman. 2022. Kindergarten Knife Attack Shines Spotlight on China’s “Lone Wolf” Stabbing Problem. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/china/chinese-kindergarten-nursery-stabbings-jianxi-b2137213.html (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Shadish, William, Thomas D. Cook, and Donald Thomas Campbell. 2002. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Boston Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, Beverley J., Barnaby C. Reeves, George Wells, Micere Thuku, Candyce Hamel, Julian Moran, David Moher, Peter Tugwell, Vivian Welch, Elizabeth Kristjansson, and et al. 2017. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358: j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, Georgios, and Mohammed H. Alghamdi. 2023. Teacher burnout in Saudi Arabia: The catastrophic role of parental disengagement. Behavioral Sciences 13: 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, Frank J., Alan C. Acock, Samuel Vuchinich, Michael W. Beets, Isaac J. Washburn, and Brian R. Flay. 2013. Preventing negative behaviors among elementary-school students through enhancing students’ social-emotional and character development. American Journal of Health Promotion 28: 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, Christopher R. 2005. Serious delinquency and gang membership. Psychiatric Times 22: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, E., M. Henderson, A. Moore, N. Price, and M.W. McGarrah. 2024. Student Reports of Bullying: Results From the 2022 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCES 2024-109); U.S. Department of Education. Washington: National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2024109 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Weeden, Marc, Howard P. Wills, Esther Kottwitz, and Debra Kamps. 2016. The effects of a class-wide behavior intervention for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders 42: 285–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, Dieter, and Suzet Tanya Lereya. 2015. Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood 100: 879–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reviews | AMSTAR 2 Overall Confidence | Type of Review |

|---|---|---|

| 1. SWPBIS—Bradshaw et al. (2012) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 2. SWPBIS—Pas et al. (2019) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 3. Positive Action—Flay (2014) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 4. SWPBIS—Molloy et al. (2013) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 5. Threat Assessment—Cornell et al. (2018) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 6. Positive Action—Snyder et al. (2013) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 7. CBPR—Gibson et al. (2015) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 8. Positive Action—Duncan et al. (2017) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 9. PBSIS—Christofferson and Callahan (2015) | High | Mixed-methods Case Study |

| 10. CW-FIT—Weeden et al. (2016) | High | Case Study |

| 11. Mindfulness-based Intervention—Meadows (2018) | High | Case Study |

| 12. PBIS—Bradshaw et al. (2020) | Moderate | Case Study |

| 13. RULER, Toolbox—Abbott (2021) | High | Case Study |

| 14. SWPBIS—Burns (2022) | High | Qualitative Case Study |

| School Violence Prevention Program | Target Population | Program Behavior Addressed | Study Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWPBIS Bradshaw et al. (2012) | Elementary, male and female | Bullying, aggressive, and disruptive behaviors | Maryland |

| 2. SWPBIS Pas et al. (2019) | Elementary and secondary, male and female | Bullying, disruptive behaviors, social-motional risks, absenteeism, and peer victimization | Maryland |

| 3. Positive Action Flay (2014) | Elementary and middle, male and female | Bullying, disruptive behavior, substance abuse, and violence | Hawaii, Chicago |

| 4. SWPBIS Molloy et al. (2013) | Elementary and secondary, male and female | Aggression or violence, substance use or possession, and defiance | United States |

| 5.Threat Assessment Cornell et al. (2018) | Elementary and secondary, male and female | Threats, homicide, battery, and weapons on campus | Virginia |

| 6. Positive Action Snyder et al. (2013) | Elementary, male and female | Violence, substance abuse, and sexual activity | Hawaii |

| 7. CBPR Gibson et al. (2015) | Elementary, male and female | Bullying | United States |

| 8. Positive Action Duncan et al. (2017) | Elementary and secondary, male and female | Social–emotional and misconduct behaviors | Chicago |

| 9. PBSIS Christofferson and Callahan (2015) | Elementary, male and female | Bullying, disruptive behavior, social-emotional risks, absenteeism, and peer victimization | New Jersey |

| 10. CW-FIT Weeden et al. (2016) | Elementary, male and female | Emotional Behavior Disorder—aggression toward others and avoidance | United States |

| 11. Mindfulness-based Intervention Meadows (2018) | Elementary and secondary, male and female | Inappropriate behaviors, school attendance, conduct problems, hyperactivity inattention problems, and peer relationships | Ohio |

| 12. PBIS Bradshaw et al. (2020) | Elementary and secondary, male and female | Bullying, aggressive, and disruptive behaviors | Maryland |

| 13. RULER, Toolbox Abbott (2021) | Elementary, teachers | Trauma-induced behaviors and physical aggression | San Francisco |

| 14. SWPBIS Burns (2022) | Elementary, teachers | Bullying, inappropriate behaviors, social–emotional risks, absenteeism, and peer victimization | Pennsylvania |

| School Violence Prevention Program | Follow-Up Period | Primary Results | Program Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWPBIS Bradshaw et al. (2012) | Pre-test, interim, Post-test | 33% reduction in office discipline-related referrals | Lowering disruptive behaviors and aggression; increasing prosocial behaviors |

| 2. SWPBIS Pas et al. (2019) | Pre-test, interim, Post-test | 1% improvement in suspension rates | Reducing suspension rates |

| 3. Positive Action Flay (2014) | Pre-test, interim, Post-test | For extreme violence, the ES was −1.39 at grade 5 in Hawaii and −0.26 and −0.54 at grades 5 and 8, respectively, in Chicago. Bullying (ES = −0.26 and −0.39 at grades 5 and 8, respectively) and disruptive behaviors (ES = −0.23 and −0.50 at grades 5 and 8, respectively) were also reduced | Reducing disruptive behaviors, bullying, violence, and suspensions |

| 4. SWPBIS Molloy et al. (2013) | Post-test (3rd year of implementation) | Reduction in office discipline referrals where expectations were taught, reward systems were in place, and violation systems were implemented | Lowering office discipline referrals where expectations were taught and reward system and violation system were in place |

| 5. Threat Assessment Cornell et al. (2018) | Post-test (2nd year of implementation) | Threat assessment team identified serious threats if made by a student above the elementary grades (odds ratio, 0.57; 95% lower and upper bound, 0.42–0.78), receiving special education services (1.27; 1.00–1.60), involving battery (1.61; 1.20–2.15), homicide (1.40; 1.07–1.82), or weapon possession (4.41; 2.80–6.96), or targeting an administrator (3.55; 1.73–7.30) | Determining the threat level as serious relative to the characteristics of the threat and the student involved |

| 6. Positive Action Snyder et al. (2013) | Post-test (5th year of implementation) | Students attending intervention schools reported significantly less violence (B = −1.410, SE = 0.296, p < 0.001, IRR = 0.244) and were mediated by positive academic behaviors | Reducing violent behaviors and increasing positive behaviors |

| 7. CBPR Gibson et al. (2015) | Pre-test, interim, Post-test | One school experienced a decrease in self-reported fear of bullying, two saw an increase in perceived peer intervention to stop bullying, and two saw an increase in perceived school staff intervention to stop bullying | Decreasing the fear of bullying and increasing interventions to stop bullying |

| 8. Positive Action Duncan et al. (2017) | Pre-test, interim, Post-test | Improvement in children’s behavioral trajectories of SECD and misconduct | Improving the trajectories of SECD and misconduct regardless of socioeconomic status |

| 9. PBSIS Christofferson and Callahan (2015) | Post-test (2nd year of implementation) | Significant decrease in discipline-related incidents (year 1, mean = 5.45; year 2, mean = 3.22) and a decrease in in-school suspensions | Significantly reducing the number of office discipline referrals and in-school suspension rates |

| 10. CW-FIT Weeden et al. (2016) | Pre-test, interim (4 weeks, 8 weeks), Post-test | Reduction in EBD behaviors and improvement in on-task behaviors (55% [43–81%] across all baseline phases) | Lowering disruptive behaviors and improving on-task behaviors and positive replacement behaviors |

| 11. Mindfulness-based Intervention Meadows (2018) | Pre-test, Post-test, and 4 months post-intervention | Overall decrease in office referral rates from pre-intervention to active intervention, with decreased office referrals in nine students and no change in the remaining students | Showing positive effects on individual behavior |

| 12. PBIS Bradshaw et al. (2020) | Pre-test, Post-test, after 3 years of implementation | Cost savings as estimated for elementary students and additional lifetime benefits from a reduction in suspensions | Reducing office referrals, suspensions, aggression, and bullying resulting in cost savings for schools and states |

| 13. RULER, Toolbox Abbott (2021) | Post-test | Teacher-reported increase in self-regulation, problem-solving skills, and cooperative social functioning skills for abused and maltreated children | Increasing self-regulation skills and building a positive classroom community |

| 14. SWPBIS Burns (2022) | Post-test | Reports of mostly minor problem behaviors among students, rather than major, by teachers | Reducing behaviors and increasing a positive classroom community |

| School Violence Prevention Program | Tool Agent | Tools for Delivery | Duration of Program Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWPBIS Bradshaw et al. (2012) | Staff (administration and teachers) | Clear Expectations: school-wide expectations for student behavior. | 4 years |

| 2. SWPBIS Pas et al. (2019) | Staff and external coach | Clear Expectations: clear expectations and a consistent response system. | 6 years |

| 3. Positive Action Flay (2014) | Staff (counselors and teachers) | Detailed Curriculum: lessons include posters, puppets, music, hands-on materials, games, activities, and journals. | 4–6 years |

| 4. SWPBIS Molloy et al. (2013) | Staff | Clear Expectations: expectations defined and taught, reward system, violation system, and district-level support. | 1 year |

| 5. Threat Assessment Cornell et al. (2018) | Threat assessment team | Clear Expectations: procedure to gather data, assess the threat, and take action. | 1 year |

| 6. Positive Action Snyder et al. (2013) | Staff (administration, counselors, and teachers) | Detailed Curriculum: 140 lessons with posters, music, certificates, assemblies, newsletters, and counselor programs. | 4–5 years |

| 7. CBPR Gibson et al. (2015) | Adult partners and youth researchers | Clear Expectations: 23–30 weekly meetings to build trust, establish operating norms, and identify issues. | 23–30 sessions in 1 year |

| 8. Positive Action Duncan et al. (2017) | Staff | Detailed Curriculum: classroom lessons focused on feeling good about oneself. | 8 sessions |

| 9. PBSIS Christofferson and Callahan (2015) | Staff (administration and teachers) | Clear Expectations/Detailed Curriculum: school-wide behavioral expectations, school climate assessment, discipline referrals, interventions, model-desired behaviors, and recognition system. | 2 years |

| 10. CW-FIT Weeden et al. (2016) | Teachers | Clear Expectations/Detailed Curriculum: goals, lessons, workbook activities, and points for appropriate behavior. | 16 sessions |

| 11. Mindfulness-based Intervention Meadows (2018) | Mindfulness facilitator | Detailed Curriculum: 30-min class periods, focusing attention, mindfulness practices, empathy building, and psychosocial skill development. | 12 weeks/24 sessions |

| 12. PBIS Bradshaw et al. (2020) | Teachers | Clear Expectations: tier 1 intervention: behavioral expectations | 3 years |

| 13. RULER, Toolbox Abbott (2021) | Teachers | Detailed Curriculum: high expectations messages, caring relationships, manners, community service, breathing tools, quiet/safe space, and SEL instruction. | Theoretical saturation reached. <1 year |

| 14. SWPBIS Burns (2022) | Teachers | Clear Expectations: expectations are defined and explicitly taught. Steps for discouraging problem behavior. | 1 year |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freeman, I.M.; Tellez, J.; Jones, A. Effectiveness of School Violence Prevention Programs in Elementary Schools in the United States: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040222

Freeman IM, Tellez J, Jones A. Effectiveness of School Violence Prevention Programs in Elementary Schools in the United States: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(4):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040222

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreeman, Ie May, Jenny Tellez, and Anissa Jones. 2024. "Effectiveness of School Violence Prevention Programs in Elementary Schools in the United States: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 13, no. 4: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040222

APA StyleFreeman, I. M., Tellez, J., & Jones, A. (2024). Effectiveness of School Violence Prevention Programs in Elementary Schools in the United States: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 13(4), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040222