“Why Here?”—Pull Factors for the Attraction of Non-EU Immigrants to Rural Areas and Smaller Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Micro- and Macro-Level Theories Explaining Migrations

Economic aspects have a wide range and go beyond employment. Peixoto (2004) notes that scholars admit enlarging the model and including non-economic aspects such as changing value systems or political and religious contexts. There are also intervening variables such as distance and travel costs between countries, household characteristics, support networks, migratory policy, and cultural and linguistic identity. There are also additional personal factors, such as life cycle position, contacts, or information sources.““push” factors operate in the economically backward regions or countries of the world (insufficient demand of labour and low wages, forcing people to search for alternative locations for better livelihoods), whereas “pull” factors operate in the economically advanced regions or countries of the world (higher demand for labour and higher wages, encouraging people to come in and stay there).”(p. 54)

“a function of aspirations and capabilities to migrate within given sets of perceived geographical opportunity structures. It distinguishes between the instrumental (means-to-an-end) and intrinsic (directly wellbeing-affecting) dimensions of human mobility. This yields a vision in which moving and staying are seen as complementary manifestations of migratory agency and in which human mobility is defined as people’s capability to choose where to live, including the option to stay, rather than as the act of moving or migrating itself.”

1.2. Motives Influencing Migration

1.3. What Is Attractive about Portugal?

- Its geographic position at the convergence of different migration systems has led to flows to Europe and in Europe, as well as from and to other continents.

- Its colonial past has prompted migrants from Portuguese-speaking African countries (e.g., Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, and Mozambique) and Brazil.

- The evolution of its demographic structure, a significant ageing population, and a constant negative natural balance have made the country dependent on migration to sustain its population.

- Its accession to the European Union, and therefore to its migration policy—namely access to the Schengen agreement, which influences inflows—has made it part of a region that is one of the most attractive places in the world for migrants (ESPON 2018).

- Finally, its sociopolitical evolution in the last few decades have attracted migrants, in part due to its open-door migration policy.

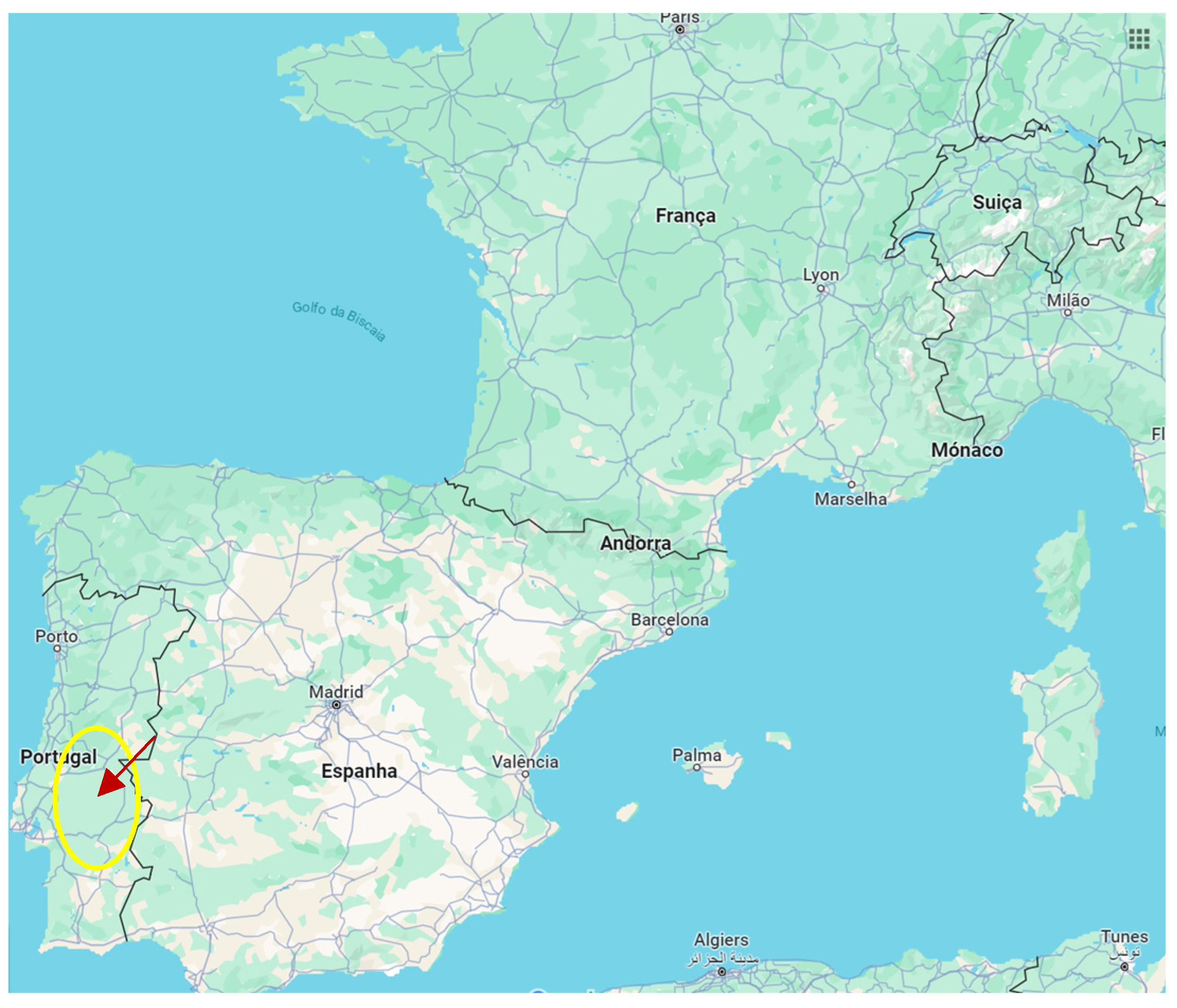

1.4. International Migrants and Rural Alentejo

2. Materials and Methods

Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Attraction of Portugal to International Immigrants

“procedures to become regularized are quicker. It may take three or four years, but he/she knows that he/she will get an authorization. In 12 months, he/she will get a residence […] it is less complex than in Italy, Spain or Germany.”(Social worker 2, male, Municipality B).

Portugal is a European country, and its health services are superior, often significantly better than in the country of origin. A similar mindset is also apparent for education.“I always say to them, the first thing to do is think about having a baby. Because having a baby means request by their children.”(Social worker, female, CLAIM 1).

Finally, participants referred to the large number and increase in Brazilians in Portugal, both in the past and at present, because Brazil was a Portuguese colony and therefore the same language is spoken, which facilitates integration. Inflows of Brazilians are permanent; however, several milestones are pointed out.“A migrant told me that she wanted her little girl to have the opportunity of a European education and to access health services. She means that here she could give them what she could never provide in her home country.”(Social worker, female, CLAIM 2).

“It is always the Brazilians!”(Social worker, female, CLAIM 3).

“And what is there for the Brazilians? [many of them in Portugal are over-qualified]”.(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

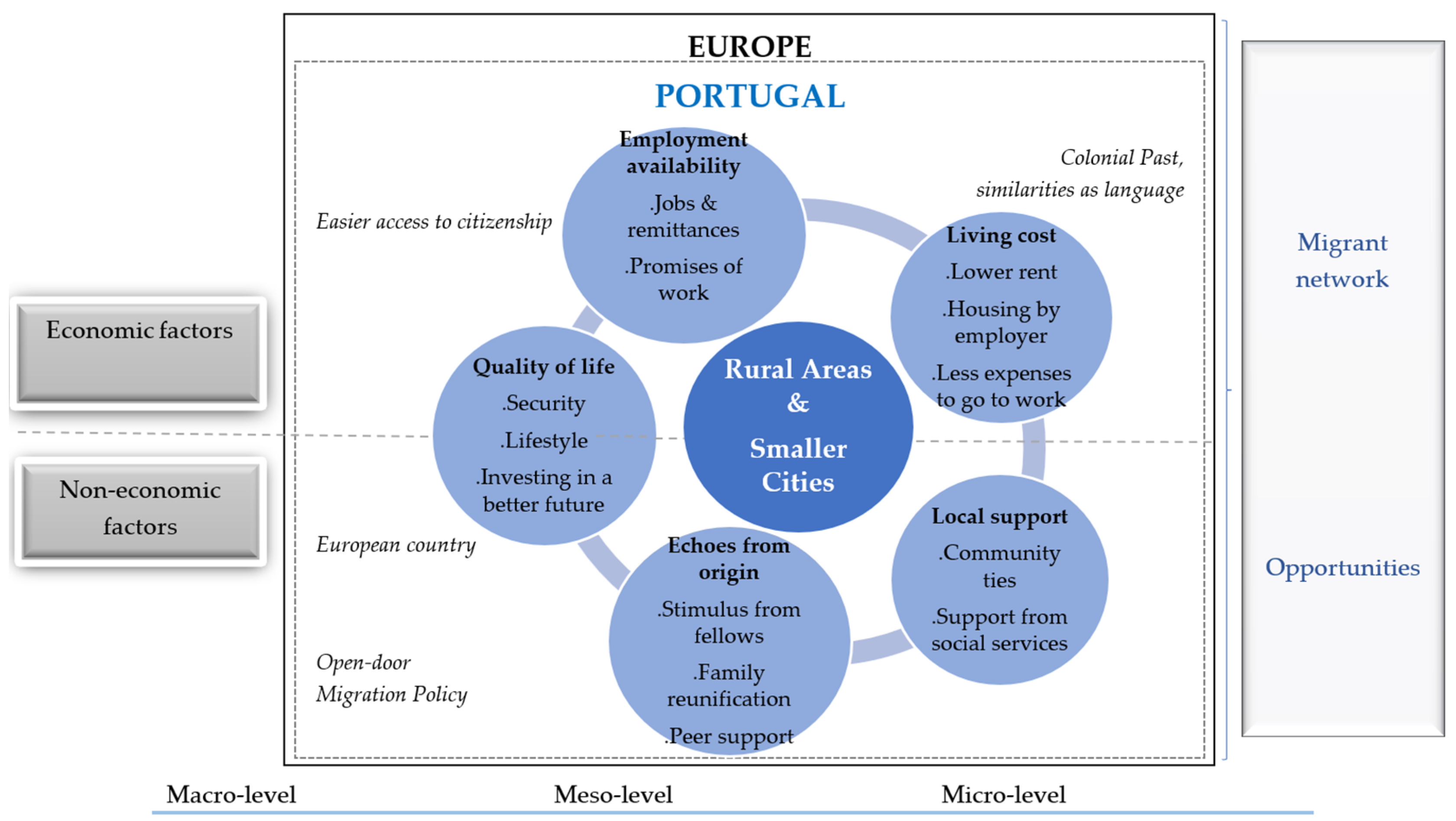

3.2. Attraction of Rural Areas and Smaller Cities

3.2.1. Employment Availability

“It was the employment, and a respectable salary. I think that a person who leaves his/her home for another one, his/her dream is to grow and develop”.(Immigrant, female, São Tomé and Príncipe).

“Here, if the two members of the couple are employed, they have guaranteed salaries at the end of the month and are able to pay bills and buy food”.(Immigrant, female, Moldova).

“They are focused on employment, for sending remittances to family to achieve better life conditions”.(Social worker, female, CLAIM 3).

“Beja nowadays has a lot of good things, for example a lot of agriculture; that’s the reason why there are so many immigrants, because of employment.”(Immigrant, female, Ukraine).

“[…] residential care for the elderly, cleaning, companies that opened doors to international immigrants, such as Tyco, Quemiche and Embraer […] here, it is not so demanding”.(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

The pursuit of workers with higher education was also mentioned:“[the capital] Lisbon is an urban center where the Portuguese language is needed. Thus, the only way to find a job is leave, and they [international migrants] come to these regions a lot”.(Social worker, female, CLAIM 3).

These regions offer seasonal jobs and employment in agriculture that can be attractive, or not, for some of the international labour force,“Immigrants who come for a specific company with a previous promise of work, is more common for active employees in a specialized field of work.”(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

“In the Alentejo, work in agriculture is temporary”.(Immigrant, male, Guinea Bissau).

“They [international immigrants] work temporarily on the olive harvest, then go away, then come back, then go to pick red fruits”.(Social worker, female, municipality).

3.2.2. Living Costs

“The city here is really calm and the cost of living is cheap”.(Immigrant, male, Guinea Bissau)

In a region marked by a shortage of housing for those who work in agriculture, employers may offer housing on their own property or nearby for newcomers. The benefit is likely to be present before coming to the region and included in the promise of work. That may represent a reduced housing cost and no travel costs to work.“The rent is lower than in Lisbon, for example”.(Immigrant, male, Cape Verde).

“[…] there are excellent examples of companies offering both an excellent accommodation service and employment […]”(Social worker, male, municipality).

In any situation, once living and working in a smaller city, expenses to go to work (among others) are less than in bigger cities:“The majority work on farms, thus a lot of them live in the own farming village”.(Psychologist, male, municipality).

“It is the cost of living, the quality of life offered here […] they [immigrants in a big city] earn to survive, and not to live! To survive…”(Social worker, female, CLAIM 3).

3.2.3. Quality of Life

“I walk on the streets fearless […] safely, any time day and night.”(Immigrant, male, Brazil).

“I live with quality. I live as any other citizen. If I want to go out for dinner with my grandchildren, I go. If we want to go to the beach, we go […] visit another city and a museum, we go. These are things that were not accessible to me in my country of origin.”(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

Investing in a better future is central for the migrants. A relevant dimension is education and health care services, as well as career development. Quality education and health care tend to be inaccessible in the migrants’ country of origin.“Here… there is a tranquility… unhurried, in contrast to the city… quality of life…”(Immigrant, female, China).

“Here you may have your family, you can provide your children with an education… there is a hospital, a proper hospital, as well as the local health center. It is same for education: there are proper schools, and there is even proper higher education.”(Immigrant, male, Brazil).

“She [an immigrant client] told me, ‘I intend to provide a European education to my children. I would like my children to have health care access. I would like them to be given opportunities impossible to get in my home country’”.(Social worker, female, CLAIM 3).

3.2.4. Local Support

“This is the easiest place to get documents. Thus, immigrants come here from other cities to request Caritas support, to apply for documents.”(Immigrant, male, Guinea Bissau).

“I used to attend six clients in a week, and nowadays I attend six, but in one day. […] Perhaps, 90% or nearly 100% are clients from outside the city.”(Social worker, male, CLAIM 1).

Similarly, community ties previously established—or if referred by someone else by word of mouth—lead to more empathy and the desire to go to that place. Close relationships with locals allow intercultural communities and improve wellbeing once diversity is present.“Whenever close relationships are the practice, they [immigrant clients] get a reference here. We become someone that they know, they can count on, and then they request our support always, even for other colleagues and other services.”(Social worker, male, municipality).

“So, you start becoming friends [with locals]…”(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

“Portalegre is a calm place that has generous people; they receive us with a warm welcome that not all cities would do.”(Immigrant, male, Guinea Bissau).

3.2.5. Echoes from Country of Origin

“Immigrants appeal to a lot of friends. And if here are jobs, they will come and stay”.(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

Family reunification is an opportunity for immigrants in rural areas and smaller cities, because there are jobs vacancies, lower cost of living, security, quality education, formal and informal support, and other conditions.“[Immigrant] people come to here, and then one after another”.(Immigrant, female, Brazil).

Participants also presented suggestions to improve the attraction of rural areas to international migrants that were very focused on infrastructural needs, such as greater accessibility to the local airport and creating high-speed motorways; as well as improving the offerings for public transport; and increasing the number of available houses through the renovation of old ones, because there is a lack of housing availability, although a large number of dwellings are empty or not habitable.“They [international migrants] aim to stay here, bring their own family, as wife and children that stay in their home country […] men want to come here, get a job and then bring their family.”(Social worker, female, CLAIM 2).

“Public transport systems should be guaranteed, housing and… social justice, because there is not social justice here, yet!”(Immigrant, male, Venezuela).

“We have here an issue about the airport that does not operate, the train does not operate. Therefore, while we don’t reinforce local infrastructure, the region and around will be hampered.”(Psychologist, female, municipality).

In addition to the dimensions explored above, the results also suggest that migrant networks are a push determinant and support, and there is also motivation to pursue new and greater economic, social, and educational opportunities outside the country of origin, which were constantly mentioned in participants’ narratives.“[…] the houses that belong to the municipality are already occupied. If they were renovated, if there was this kind of investment… I mean there are manifold derelict and inhabited properties in the old town, a lot of them…”(Social worker, female, CLAIM 3).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons (International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2019). This study focuses primarily on non-EU migrants, as it is co-funded by the European Union Asylum Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF). |

References

- Basabe, Nekane, Anna Zlobina, and Darío Páez. 2004. Integración Socio-Cultural y Adaptación Psicológica de los Inmigrantes Extranjeros en el País Vasco. Cuadernos Sociológicos Vascos. Vitoria: Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Gary. 1964. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, Isaiah. 1969. Four Essays on Liberty. London and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, Norman. 2010. Designing Social Research, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Vitoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkus, Mindaugas, Alma Maciulyte-Sniukiene, Kristina Matuzeviciute, and Vida Davidaviciene. 2018. Society’s attitudes towards impact of immigration: Case of EU countries. Marketing and Management of Innovations 9: 338–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Vicente, Enrique Castro-Sánchez, Miguel Angél Díaz-Herrera, Carmen Sarabia-Cobo, Raúl Juárez-Vela, and Edurne Zabaleta-Del Olmo. 2019. Motivations, beliefs, and expectations of Spanish nurses planning migration for economic reasons: A cross-sectional, web-based survey. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 51: 178–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carling, Jørgen. 2002. Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28: 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Cristiana, and Catarina Oliveira. 2017. Uma leitura de género sobre mobilidades e acessibilidades em meio rural. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios 35: 129–46. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/cidades/599 (accessed on 5 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, João M. 2021. A imigração e a agricultura no Alentejo no século XXI. In Revista Migrações. Observatório das Migrações, no. 17. Lisboa: ACM, pp. 87–104. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/26077/1/article_89680.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Castro, Fátima Velez. 2011. Imigração e Desenvolvimento em Regiões de Baixas Densidades. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Collantes, Fernando, Vicente Pinilla, Luis Antonio Sáez, and Javier Silvestre. 2013. Reducing depopulation in rural Spain: The impact of immigration. Population, Space and Place 20: 606–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaika, Mathias, and Constantin Reinprecht. 2020. Drivers of Migration: A Synthesis of Knowledge. Working Papers. Paper 163. Amsterdam: International Migration Institute. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas, Hein. 2021. A theory of migration: The aspirations—Capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies 9: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, Elisete. 2024. Retaining non-EU immigrants in rural areas to sustain depopulated regions: Motives to remain. Societies 14: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, Elisete, Raquel Melo, and Luiza Mira. 2023. Perspetivas sobre a Imigração em Territórios de Baixa Densidade—Potencial de retoma e de inovação. In Práticas e Políticas—Inspiradoras e Inovadoras com Imigrantes. Edited by E. Diogo and M. Raquel. Porto: Edições Esgotadas, pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dohlman, Lena, Matthew DiMeglio, Jihane Hajj, and Krzysztof Laudanski. 2019. Global brain drain: How can the Maslow theory of motivation improve our understanding of physician migration? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 1182. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/7/1182 (accessed on 14 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlinghagen, Marcel. 2021. Migration motives, timing, and outcomes of internationally mobile couples. In The Global Lives of German Migrants—Consequences of International Migration across the Life Course. IMISCOE Research Series; Edited by Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider and Nils Witte. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 162–71. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/48701/1/9783030674984.pdf#page=162 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- ESPON. 2018. Transnational Observation—Fighting Rural Depopulation in Southern Europe; Luxembourg: ESPON EGTC. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/af-espon_spain_02052018-en.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- European Commission. 2020. Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027; Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0758 (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- European Commission. 2023a. Estatísticas Sobre os Fluxos Migratórios para a Europa; Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/promoting-our-european-way-life/statistics-migration-europe_pt (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- European Commission. 2023b. Supporting Policy with Scientific Evidence; Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/visualisation/competence-framework-%E2%80%98science-policy%E2%80%99-researchers_en (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- European Union. 2023. Rural Vision—Rural Vision Ten Shared Goals; Brussels: European Union. Available online: https://rural-vision.europa.eu/rural-vision/shared-goals_en (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Fischer-Souan, Maricia. 2019. Between ‘labour migration’ and ‘new European mobilities’: Motivations for migration of Southern and Eastern Europeans in the EU. Social Inclusion 7: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe. 2005. Métodos Qualitativos na Investigação Científica. Lisboa: Monitor. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, Uwe. 2013. Introdução à Metodologia de Pesquisa. Porto Alegre: Penso. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, Moya, and Rebecca Kay. 2017. Migrants’ experiences of material and emotional security in rural Scotland: Implications for longer-term settlement. Journal of Rural Studies 52: 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Maria Lucinda, Alina Esteves, and Luís Moreno. 2021. Migration and the reconfiguration of rural places: The accommodation of difference in Odemira, Portugal. Population, Space and Place 27: e2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, Jean-Pierre. 2020. Integration of Migrants in Middle and Small Cities and in Rural Areas in Europe; Brussels: Commission for Citizenship, Governance, Institutional and External Affairs. European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/integration-migrants-middle-and-small-cities-and-rural-areas-europe_en (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Góis, Pedro. 2023. Ainda entre periferias e um centro: O lugar de Portugal no sistema migratório global. In Práticas e Políticas—Inspiradoras e Inovadoras com Imigrantes. Edited by Elisete Diogo and Raquel Melo. Porto: Edições Esgotadas, pp. 29–40. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Ana_Couteiro_Pr%C3%A1ticas_e_Pol%C3%Adticas?id=wLOxEAAAQBAJ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Góis, Pedro, and José Carlos Marques. 2018. Retrato de um Portugal migrante: A evolução da emigração, da imigração e do seu estudo nos últimos 40 anos. E-Cadernos CES 29: 2018. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/eces/3307 (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Goodson, Lisa, and Aleksandra Grzymala-Kazlowska. 2017. Researching Migration in a Superdiverse Society: Challenges, Methods, Concerns and Promises. Sociological Research Online 22: 15–27. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.5153/sro.4168 (accessed on 1 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, Friedrich. 2008. Education and the Integration of Migrants: Challenges for European Education Systems Arising from Immigration and Strategies for the Successful Integration of Migrant Children in European Schools and Societies. Bamberg: Europäisches Forum für Migrationsstudien (efms): Institut an der Universität Bamberg. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-192500 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). 2023a. Dinâmicas Territoriais; Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=66320870&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). 2023b. Estatísticas Demográficas; Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&userLoadSave=Load&userTableOrder=9956&tipoSeleccao=1&contexto=pq&selTab=tab1&submitLoad=true (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. Glossary on Migration. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM). Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Korpi, Martin, and William A. W. Clark. 2017. Human capital theory and internal migration: Do average outcomes distort our view of migrant motives? Migration Letters 14: 237–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, Jussi P., Daniel Rauhut, and Marika Gruber. 2023. On the potential of immigration for the remote areas of Europe: An introduction. In Assessing the Social Impact of Immigration in Europe. Edited by Jussi P. Laine, Daniel Rauhut and Marika Gruber. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Everett. 1966. A Theory of Migration. Demography 3: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritti, Rosário, Nuno Nunes, João Emílio Alves, and Fernando Diogo. 2019. Desigualdades sociais e desenvolvimento em Portugal: Um olhar à escala regional e aos territórios de baixa densidade. Sociologia Online 19: 102–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAreavey, Ruth, and Neil Argent. 2018. New immigration destinations (NID): Unravelling the challenges and opportunities for migrants and for host communities. Journal of Rural Studies 64: 148–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAreavey, Ruth. 2017. New Immigration Destinations—Migrating to Rural and Peripheral Areas. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Migration Data Portal. 2021. Migration Drivers. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/migration-drivers (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Morén-Alegret, Ricard, Josepha Milazzo, Francesc Romagosa, and Giorgos Kallis. 2021. ‘Cosmovillagers’ as sustainable rural development actors in mountain hamlets? International immigrant entrepreneurs’ perceptions of sustainability in the Lleida Pyrenees. European Countryside 13: 267–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, Bruno Mendes da. 2019. A Problemática dos Territórios de Baixa Densidade: Quatro Estudos de Caso. Master’s thesis, ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/19336/1/master_bruno_mendes_mota.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Natale, Fabrizio, Sona Kalantaryan, Marco Scipioni, Alfredo Alessandrini, and Arianna Pasa. 2019. Migration in EU Rural Areas; Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC116919 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- O’Reilly, Karen. 2023. Migration Theories: A Critical Overview. In Routledge Handbook of Immigration and Refugee Studies, 2nd ed. Edited by Anna Triandafyllidou. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Catarina Reis, ed. 2022. Indicadores de Integração de Imigrantes—Relatório Estatístico Anual 2023; Coleção Imigração em Números do Observatório das Migrações. Lisbon: Observatório das Migrações. Available online: https://www.om.acm.gov.pt/documents/58428/383402/Relatorio+Estatistico+Anual+-+Indicadores+de+Integracao+de+Imigrantes+2022.pdf/eccd6a1b-5860-4ac4-b0ad-a391e69c3bed (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Padilla, Beatriz, and Alejandra Ortiz. 2012. Fluxos migratórios em Portugal: Do boom migratório à desaceleração no contexto de crise. Balanços e Desafios. Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana 39: 159–84. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/remhu/a/VgJxSRjsTTzndXdxPpkHYHD/abstract/?lang=pt# (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Peixoto, João. 2004. As Teorias Explicativas das Migrações: Teorias Micro e Macrossociológicas. SOCIUS Working Papers. No. 11/2004. Lisboa: Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão—Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. Available online: https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/2037 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Piore, Michele J. 1979. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pordata. 2021. Saldos Populacionais Anuais: Total, Natural e Migratório. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Saldos+populacionais+anuais+total++natural+e+migrat%C3%B3rio-657 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Pordata. 2022. População Estrangeira com Estatuto Legal de Residente: Total e por Algumas Nacionalidades. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/db/municipios/ambiente+de+consulta/tabela (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Pordata. 2023. Censos de Portugal em 2021—Por Tema e Concelho. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/censos/resultados/populacao-alentejo-592 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Quintino, Ana. 2018. Efeitos Demográficos e Económicos das Migrações em Portugal: O Caso da Segurança Social. Master’s thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/36350/1/ulfc124640_tm_Ana_Sofia_Quintino.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Rine, Christine M. 2018. The role of social workers in immigrant and refugee welfare. Health & Social Work 43: 209–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, Rosario, and Luis Camarero. 2018. Foreign immigrants in depopulated rural areas: Local social services and the construction of welcoming communities. Social Inclusion 6: 337–46. Available online: https://www.cogitatiopress.com/socialinclusion/article/view/1530 (accessed on 1 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Secundo, Giustina, Valentina Ndou, Pasquale Del Vecchio, and Gianluigi De Pascale. 2020. Sustainable development, intellectual capital and technology policies: A structured literature review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 153: 119917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras/Gabinete de Estudos, Planeamento e Formação (SEF/GEPF). 2023. Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo 2022. Available online: https://www.sef.pt/pt/Documents/RIFA2021%20vfin2.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Sistema de Segurança Interna. 2022. Relatório Anual de Segurança Interna; Lisboa: Sistema de Segurança Interna. Available online: https://www.portugal.gov.pt/download-ficheiros/ficheiro.aspx?v=%3D%3DBQAAAB%2BLCAAAAAAABAAzNDazMAQAhxRa3gUAAAA%3D (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Solano, G., and T. Huddleston. 2020. Migrant Integration Policy Index 2020. Available online: www.mipex.eu/portugal (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Suciu, Marta-Christina, and Diana-Florentina Năsulea. 2019. Intellectual capital and creative economy as key drivers for competitiveness towards a smart and sustainable development: Challenges and opportunities for cultural and creative communities. In Intellectual Capital Management as a Driver of Sustainability. Edited by Florinda Matos, Valter Vairinhos, Paulo Maurício Selig and Leif Edvinsson. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, E., and S. Schwartz. 2001. Motivation for emigration, values, wellbeing, and identification among young Russian Jews. International Journal of Psychology 36: 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. 2015. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Wadood, Syed Naimul, Nayeema Nusrat Choudhury, and Abul Kalam Azad. 2021. Does migration theory explain international migration from Bangladesh? A primer review. Social Science Review 38: 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Chris, and Andreea Constantin. 2021. Why recruit temporary sponsored skilled migrants? A human capital theory analysis of employer motivations in Australia. Australian Journal of Management 46: 151–73. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0312896219895061 (accessed on 3 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Yap, Lorene. 1977. The Attraction of Cities: A Review of the Migration Literature. Journal of Development Economics 4: 239–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diogo, E. “Why Here?”—Pull Factors for the Attraction of Non-EU Immigrants to Rural Areas and Smaller Cities. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040184

Diogo E. “Why Here?”—Pull Factors for the Attraction of Non-EU Immigrants to Rural Areas and Smaller Cities. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(4):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040184

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiogo, Elisete. 2024. "“Why Here?”—Pull Factors for the Attraction of Non-EU Immigrants to Rural Areas and Smaller Cities" Social Sciences 13, no. 4: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040184

APA StyleDiogo, E. (2024). “Why Here?”—Pull Factors for the Attraction of Non-EU Immigrants to Rural Areas and Smaller Cities. Social Sciences, 13(4), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040184