Abstract

Introduction: Public health disinformation is a significant problem as demonstrated by the recent scientific literature on the COVID-19 pandemic. However, further studies that analyse the presence of the disinformation mitigation strategies in public health initiatives within specific contexts and which contains a multidimensional approach (gender, social and environmental) are required. Evidence shows that disinformation, information overload, misinformation or fake news on health issues are also influenced by these issues. Objective: The inclusion of the health disinformation dimension within national public implemented by the governments of Argentina and Spain before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, this paper incorporated a gender-based approach and social and environmental determinants in order to identify the limitations of these initiatives and offer certain recommendations. We conducted a descriptive, qualitative and quantitative study, as well as content analysis. We focused on documents from the websites of the national health ministries of Argentina and Spain, and digital repositories of regulations at the national level. Various strategies for systematic searches on government websites were designed and implemented. This included manual searches on Google. The first step involved a general analysis of all documents found by the searches, followed by a qualitative analysis of the documents that were related to health issues. Based on this work, a comprehensive and flexible framework of (pre-established and emerging) dimensions and categories of health disinformation and infodemics was generated. Results. The work was based on a total of 202 documents (both downloadable information and information included in websites); 117 for Argentina and 85 for Spain. Of the total, 60.9% were published during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the second stage of the analysis, 55 texts were selected for Argentina and 47 for Spain. In both countries, the central communications approach used was disinformation and/or infodemics (although definitions such as fake news were also used). They were mainly linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, but other emerging health problems were also detected to a lesser degree. However, disinformation (or a related concept) was prominently present in only 17 documents in Argentina and 3 documents in Spain. In terms of document type, working materials were foremost in Argentina (44.4%) and Spain (37.6%), with little presence of policy, regulatory and evaluation documents (only 5). Gender binary language was predominantly used in these texts. Vulnerable groups and social determinants were poorly included. Environmental determinants were mentioned in conjunction with health disinformation in only one paper on the use of plastics and its impact on human health in Argentina, and in another paper from the Global Summit on Climate and Health in Spain. Conclusions: Based on the document analysis, the inclusion of health disinformation within public actions in both countries before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, was detected. However, different limitations were observed: it was clear that the problem was strongly linked to the health emergency and did not extend much beyond that. Health disinformation was secondary and did not play a key role in public policy nor did it have greater institutional importance. Limitations were also detected in terms of gender perspectives, vulnerable groups and social and environmental determinants linked to health disinformation, displaying a reductionist approach. Based on these results, this paper makes certain policy recommendations.

1. Introduction

Health disinformation and infodemics were in the limelight during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hu et al. 2023). However, this is not a new phenomenon as risk communication had been studied in other outbreaks such as Ebola, Zika and yellow fever, prior to the pandemic (Toppenberg-Pejcic et al. 2019; WHO 2024).

As demonstrated in a previous review, misinformation has been studied in relation to other topics such as vaccination, Ebola, Zika, nutrition, cancer, water fluoridation and smoking (Wang et al. 2019).

Following the interpretation of the World Health Organisation (WHO), different concepts related to health disinformation may be distinguished: misinformation (false information that is spread without an intent to mislead), infodemic (an avalanche of information) and disinformation (to create or spread information with the full awareness that it is false) (WHO 2024, n.d.).

Disinformation is a serious public health problem, even more so in crisis contexts, and must be addressed as a knowledge generation and public health practice problem. In an update on its website in 2024, the WHO indicates that public health disinformation is “is a distinct type of information risk which, unlike misinformation, is created with malicious intent to sow discord, disharmony and mistrust in targets such as government agencies, scientific experts, public health agencies, private sector and law enforcement, among others.” (WHO 2024).

In terms of knowledge generation, a previous systematic review of reviews has highlighted the low methodological quality of studies on health misinformation that were published during health crises (Do Nascimento et al. 2022).

The scientific literature also showed that a considerable part of the messages on how to prevent COVID-19 that were circulated by governments in different Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries were flawed and there were few communication products and specific messages intended to raise awareness of the importance of combating infodemics or having infodemic management strategies (Haraki 2021; Moyano and Mendivil 2021). The results of other study in Spain indicate that health disinformation occupies a small place in the fact-checking agenda (Costa-Sánchez et al. 2023).

Communications errors were also observed in other continents such as Africa during the pandemic (Seytre 2020). These large-scale miscommunications are disquieting.

Gender and intersectionality-based research (Crenshaw 1989, 1991; Carbado et al. 2013) on health disinformation is still underdeveloped. It should be noted that intersectionality is defined as an approach that recognises the combined effects of different social categories (elderly people, women, LGBTQ+ groups, minorities, populations with low socio-economic and educational levels, amongst other categories of interest). These interactions define people’s experiences and opportunities (Humphries et al. 2023).

Moreover, the academic literature on health disinformation and gender suffers from limitations including few published studies, authorship of the articles (mostly men), limited gender focus (mostly binary), low presence of vulnerable groups (children, adolescents, ethnically diverse groups, the disabled, elderly and sexually diverse). Most studies focused on COVID-19. However, the results reported in these papers displayed the presence of numerous inequalities between gender and health disinformation (Moyano et al. 2024).

In Argentina (as in other LAC countries) (Moyano and Mendivil 2021) and Spain (Villegas-Tripiana et al. 2020), previous studies have demonstrated that limited attention was paid to gender and other determinants of social health in communication initiatives by governments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to study the consequences of disinformation from the perspectives of gender, intersectionality (Crenshaw 1989, 1991; Carbado et al. 2013) and social determinants (WHO 2010). The scientific literature has demonstrated that the effects of health disinformation are negative and unequal depending on the gender. Women, sexually diverse groups, the elderly and populations with low levels of education and social status are the most affected groups (Moyano et al. 2024).

Misinformation in climate crises and extreme weather events such as storms, floods and wildfires can have serious consequences, not only by undermining emergency responses in the short term, but also by influencing the long-term public perception of climate change (Daume 2024). Yet, to the best of our knowledge, there is little to no research on health disinformation which includes environmental determinants.

The origins of disinformation have varied over time. Today, disinformation campaigns are a part of geopolitical tensions and a broader agenda aimed at sowing confusion regarding facts and their origins, exacerbating political divisions, eroding trust in civilian and scientific institutions, or undermining confidence in governments (WHO 2024). Therefore, the problem of health disinformation needs to be addressed through broad and multidimensional approaches.

The aim of this paper is to bring together theory and practice by analysing two representative case studies from Latin America and Caribbean and Europe (Argentina and Spain respectively). We seek to analyse the inclusion of disinformation within public health initiatives from a gender, social and environmental perspective. We also seek to identify policy limitations and potential, to offer certain recommendations on the issue.

In this work, the case studies were selected with a specific purpose in mind. Prior research in both countries during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that communication strategies did not focus on gender and other social determinants (Moyano and Mendivil 2021; Villegas-Tripiana et al. 2020).

During the health emergency, a comparative study of the two nations highlighted the presence of disinformation on social media (Gamir-Ríos and Tarullo 2022).

It is worth noting that both Argentina (Ministry of Health of Argentina n.d.) and Spain (Spanish Ministry of Health n.d.) have national ministries of health, their websites are updated (Ministry of Health of Argentina n.d.; Spanish Ministry of Health n.d.), and there are laws in place with regard to accessing public information (Act 27.275 on the right of access to public information in Argentina, and Act 19/2013 on transparency, access to public information and good governance in Spain).

Regarding environmental aspects, both nations have signed and ratified international treaties such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement (United Nations n.d.a, n.d.b).

Based on the existing literature on social inequality, there are comparative studies at the international level were analysed in terms of welfare regimes (Ayos and Pla 2021). From this perspective, Argentina and Spain follow the Welfare State model, with social protection and health policies (Navarro Ruvalcaba 2006). The COVID-19 health crisis has highlighted the importance of these protection systems in addressing health challenges, and their economic and social impacts (ECLAC 2022).

However, in-depth empirical analysis of public health disinformation by means of international case studies remains an under-explored area as of now. This study first analysed initiatives to combat health disinformation in each country, and then, based on the emerging data, compared the two cases, highlighting similar and divergent aspects.

2. Methods

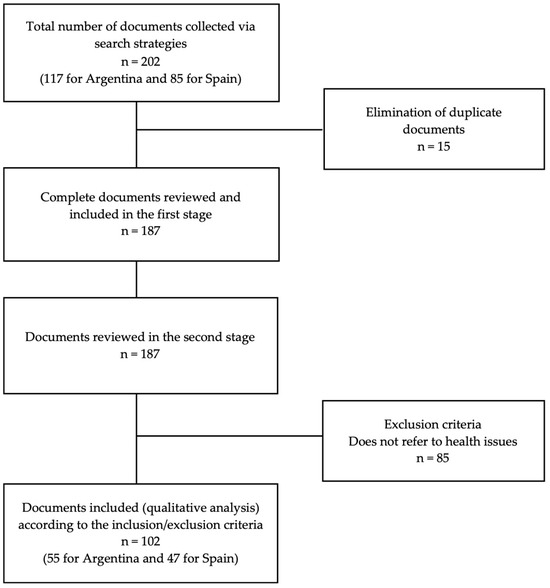

A systematic online search of public documents (Dalglish et al. 2020) was conducted on the official websites of public health institutions of Argentina and Spain, together with other sources. Having compiled a total of 202 documents, a content analysis (Altheide and Schneider 2013) was conducted on 102 documents that met the inclusion criteria; 55 texts were selected for Argentina and 47 for Spain (Figure 1). The analysis was both qualitative and quantitative in nature, albeit with greater focus on the former.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the review of public documents according to different analysis stages and inclusion and exclusion criteria. Source: Authors’ own.

Of the total number of documents from Argentina and Spain, 60.9% were published during the COVID-19 pandemic, 13.4% before, and 13.4% afterwards. There was no publication date for 25 papers (no data); however, most of them dealt with COVID-19. Initially, all types of public documents found were selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Type of selected public document, by country (n = 202).

Table 1 displays the results related to public document type; working documents (meeting or committee reports) were the main document type in both countries. However, there were differences in certain categories; a higher proportion of scientific documents were observed in the case of Spain, while documents on implementation were observed in the case of Argentina. With regard to the time of publication, most of the documents had been published during the COVID-19 pandemic in both countries.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In the first stage, all documents were included without any time or type-based restrictions. These documents were located by entering search terms related to disinformation/infodemics in the websites of national health ministries (other ministry websites were included only if they were detected by the initial searches). Documents with only one section mentioning disinformation (or a related concept) were also included. If a link to a document of interest was online, but the document itself was unavailable, it was not included.

In the second stage (qualitative analysis), the primary inclusion criterion was that this paper should focus on health issues before, during or after the pandemic. The cut-off point for the latter period was defined by the date on which the WHO announced the end of the international health emergency (5 May 2023) (WHO 2023).

With regard to the use of gendered language and other qualitative categories, the analysis mainly focused on text sections corresponding to disinformation (or related concepts).

The second stage did not include documents with a local scope, ones that did not mention infodemics/disinformation on at least one occasion and were not issued by national governments or public institutions. When different versions of a document were available, only the final or most up-to-date version was included.

Academic publications in scientific journals were only included during this stage if they were linked to health ministry websites, reported results on health disinformation, the lead author was a member of a state-level public body, and when the studies were conducted in at least two autonomous communities/provinces. Texts by international bodies (without the state government’s involvement) were not included. In the case of regulatory documents, only those that included disinformation in the title were selected and reviewed.

2.2. Search and Data Collection Strategies

Systematic searches were conducted during the last two weeks of June 2024. For greater reliability, a pilot study of the strategies was carried out until the final versions were consolidated.

Complementary searches were conducted on Google and all titles returned by this search engine were reviewed. Regulatory documents were searched on the “Argentinian Legal Information System (SAIJ)” (SAIJ n.d.) website in Argentina and the “Official State Gazette Agency” (Official State Gazette Agency n.d.) website in Spain.

2.2.1. Health Websites

Different searches were conducted on the website of the Spanish Ministry of Health (Spanish Ministry of Health n.d.) by means of the “advanced search” option; selecting the field “with at least one word” and “anywhere in the document”. The following keywords were entered: “infodemic” and “disinformation”.

The following keywords were entered in the search engine of the Ministry of Health of Argentina (Ministry of Health of Argentina n.d.): “infodemic” and “disinformation”.

2.2.2. Websites of Standards and Other Regulations

Within the website of the “Official State Gazette Agency” (in Spain) (Official State Gazette Agency n.d.) the field “Legislation, simple search” was selected, followed by “state legislation”.

In the “Argentinian Legal Information System (SAIJ)” website (for Argentina) (SAIJ n.d.), the “search engine” was selected and the option “All” was checked in the document type field.

On both legislative websites, separate searches were conducted for “infodemic” and “disinformation”.

2.2.3. Google

The “Advanced Search” function was used and the field “all these words” was selected. The key words were:

“disinformation” OR “infodemic” AND “health” AND “Spain” AND “legislation” OR “policy”.

In another independent search:

“disinformation” OR “infodemic” AND “health” AND “Argentina” AND “legislation” OR “policy”.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

All links were logged and the selected documents were downloaded (or screenshots taken in cases where the information could not be downloaded) in order to preserve the information.

An exhaustive analysis of duplicate documents and links (i.e., where the same document or link is found more than once) was conducted by means of an automated process (in Excel) and then via a manual review by a researcher (DLM).

In order to improve data reliability and reduce potential biases, all documents were double-checked. The functionality of the links was tested at least thrice at different times.

The information collected was logged and processed using an online form (Google Forms) (Appendix A). This instrument included the established dimensions and categories and open fields for new information. The entire database was reviewed by the research team (DLM, MSAT, MAM).

A content analysis (Altheide and Schneider 2013) was conducted via manual coding and then re-coding with Atlas.ti version 23. Textual phrases from the documents were selected to illustrate the results. Absolute and relative frequencies were used for quantitative indicators.

To improve the internal validity of this study, three researchers reviewed and commented on the data analysis (DLM, MSAT, MAM). The methodological guidelines established for the qualitative analysis were followed (Tong et al. 2007; Arroyo Menéndez and Rodríguez 2012).

2.4. Dimensions and Categories of Analysis

Table 2 displays the (pre-established and emerging) dimensions and categories used to analyse the public documents.

Table 2.

Dimensions and categories of analysis.

2.5. Ethical Aspects

This study was based on public documents available online. Access to public information is regulated by Act 27.275 in Argentina, and by Act 19/2013 in Spain.

3. Results

3.1. General Description of the Documents

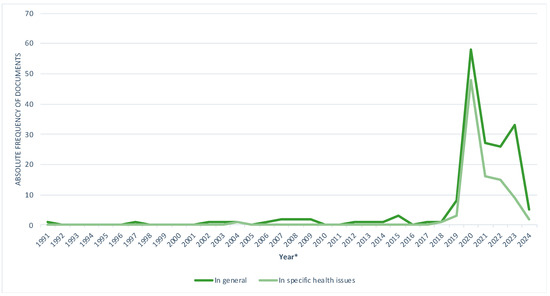

As shown in Figure 2, initial publications on the subject date back to the 1990s, although they reached their highest volume in 2020.

Figure 2.

Historical evolution of the publication of public documents including disinformation in Argentina and Spain. Source: Authors’ own. * In the case of scientific articles, the date of data collection was assigned.

Of the total of 202 documents that were assessed, 75 were published by health ministries, while the rest were published on other ministry websites: justice, economy, the presidency, cabinet of ministers, science and technology, human capital, defence, and social rights.

3.2. Specific Description of Health-Related Documents

Table 3 demonstrates that in both cases the health-related documents (including disinformation) were on matters related to COVID-19, and the predominant gender approach was binary. It is also worth noting that the main focus was on disinformation and, to a lesser extent, on infodemics.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the health-related documents analysed, by country (n = 102).

There was no distinction drawn between rural and urban areas in 95.1% of the documents included in the second stage of analysis, and practically all of them were drafted by institutions (98%).

With regard to the inclusion of formal evaluation, only five documents included any information on this aspect (especially in policy or legal documents, although only in Spain). However, in no case was the evaluation information linked to health disinformation. Information on budgets was also scarce (three documents).

Only a few documents revealed a cross-sectoral approach (in terms of the authors of the publication or as a statement within the text) (31/102). One or more state agencies were involved in the cases detected, together with other institutions such as international organisations, professional or academic associations, the private sector, communities or NGOs.

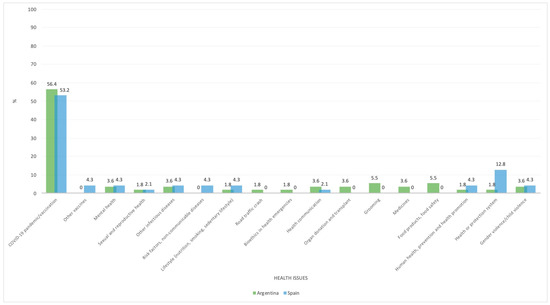

In both countries, the health issues addressed in the documents were: the COVID-19 (or vaccination) pandemic. However other topics were also found such as: lifestyle (nutrition, alcohol or tobacco use), other infectious diseases (such as Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya, HIV, STIs or monkeypox), other vaccines, mental health, sexual and reproductive health, and violence (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Health issues addressed in the public documents from Argentina and Spain. Source: Authors’ own.

3.3. Description of the Qualitative Analysis

The results of the content analysis were classified under 4 main dimensions and their categories. The categories were included regardless of the number of times they were detected in the documents.

There was no significant difference between the case studies (Argentina and Spain), in terms of the main dimensions. For this reason, a pooled analysis of the two countries was opted for, indicating differences and similarities only where they were detected.

Figure 4 displays the word cloud generated from the analysed fragments related to disinformation. An initial list of 1938 words was used for this process, of which 1179 words were selected as being of interest to this study. Within the group of included words, frequencies of occurrence ranged from 112 to 1. The words with the highest presence in the analysed texts were: health (3.0%), disinformation (2.8%) and information (2.0%).

Figure 4.

Word cloud derived from the qualitative analysis. Source: Authors’ own created with Atlas.ti, version 23.

- 1.

- Dimension. Addressing health (dis)information

Within this dimension, health disinformation was a key focus of only 20 documents (17 in Argentina and 3 in Spain).

It is worth pointing out that the concepts of infodemics and fake news have been present in health documents published from 2020 onwards. The concept of disinformation was found in papers published before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In some cases, other codes related to disinformation were also included misinformation, information overload or hoaxes.

During the pandemic, there were various health topics linked to disinformation; however, they were mainly focused on COVID-19 and vaccines. Prior to the pandemic, the topics were linked to chronic health conditions, such as organ donation in Argentina or violence and risk factors in Spain.

In both countries, the inclusion of disinformation topic (or other related concepts) was found in verbatim quotes from the minutes of meetings involving key government figures, such as ministers, secretaries, and other state stakeholders. These fragments were not only found in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also in connection to other health problems, as mentioned above.

Fragments of texts containing disinformation strongly linked to elements of the mental health category were observed in both countries, and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are phrases or words that include: warnings, anxiety, fears, doubts, emotions, prejudices, reproduction of stereotypes, stigmatisation, myths, hate speech, mistrust, false beliefs, ignorance, confusion, uncertainty, and discriminatory practices.

In both cases, disinformation was often linked to the “danger” or “risk” category. This was especially the case during the COVID-19 health emergency, although the risk of disinformation also appeared for other infectious diseases such as influenza, for example.

In a scientific study conducted in two autonomous communities in Spain (the Community of Madrid and the Valencian Community), the danger of disinformation regarding influenza was observed in the discourse of health professionals (URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/resp/revista_cdrom/VOL95/C_ESPECIALES/RS95C_202103058.pdf. Accessed on 21 July 2024). In Argentina, other documents highlighted the risk of disinformation with regard to sensitive issues such as organ donation and transplantation.

“It has also shed light on people’s confidence in Public Health in our country, the need to provide access to truthful information in sensitive matters such as health and the importance of combating disinformation and fake news that may pose a real risk to public health, developing specific policies aimed at protecting citizens”(Excerpt from a working paper on the Ukrainian health system and vaccinating people, 2022, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=5846. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

Some texts from Spain and Argentina point out that disinformation or infodemics and their impact are exacerbated through Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and social networks.

“Disinformation can cause enormous harm to citizens. Its harmful effect is magnified exponentially by the misuse of new technologies and social networks. That is why I would like to request everybody to actively work to fight against and report the hoaxes that reach us about the epidemic”(Excerpt from a working paper on updating information related to COVID-19, 2020, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinetePrensa/notaPrensa/pdf/08.04080520142537303.pdf. Accessed on 19 July 2024)

In both cases there was a marked presence of different codes related to the taking action category, indicating measures such as: the proactive role of individuals, the role of the media in disseminating correct messages and the importance of using official sources. Within Spain, the role of journalists in the age of disinformation and artificial intelligence was also highlighted.

Within Argentina, recommendations for broadcasters to avoid promoting fake news during the pandemic were found. Among these recommendations, “prioritising respect for individuals” and “avoiding a stigmatising or discriminatory view of certain social groups” are especially worth noting.

“The acting Health Minister also stressed the role of science journalists “in the era of disinformation and Artificial Intelligence”, as well as the importance of improving access to information, the quality of “reliable and safe” sources of information, and including the point of view of young people in order to achieve the objectives that have been set”(Excerpt from a working paper examining the role of specialised media in prevention and the promotion of good health, 2023, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=6268. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

Some texts contained sentences indicating the role of institutions in reducing disinformation. Aspects such as access to public information, open government and state accountability were identified in Argentinian texts. Similar aspects such as the government’s initiative and information transparency were also detected in the Spanish texts. These aspects were observed not only with regard to COVID-19, but also other topics such as violence in Spain or road accidents in Argentina.

“This is why publishing figures without demonstrating their truthfulness or how they were obtained is a serious act of disinformation. It also undermines the State’s institutional role and the efforts of all people involved in the process, who work honestly, collecting sensitive and key information with the seriousness required by scientific techniques and methods”(Excerpt from a policy report on road accident data, 2021, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/datos-oficiales-de-siniestralidad-vial. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

“With these hearings we hope to promote and contribute to substantiating one of the fundamental principles underlying the government’s actions since the beginning of this crisis: transparency of information. It is our conviction that communication is always essential in public health. But it makes special sense in these times when fake news and hoaxes are airing false information and, on many occasions, damaging the common cause of defeating the disease”(Textual excerpt from a working document on update the information regarding to COVID-19, 2020, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinetePrensa/notaPrensa/pdf/08.04080520142537303.pdf. Accessed on 19 July 2024)

Other textual elements related to actions to counter disinformation, such as the role of monitoring disinformation during the pandemic, were also noted. For example, in Argentina, an action to launch an open platform on vaccine information was detected, as well as another to counter fake news. The role of the Ombudsman’s Office, which received and processed more than 400 complaints related to disinformation during the first stage of the pandemic, was also highlighted in the case of Argentina.

In Spain, an active monitoring of disinformation related to different topics such as the management of nursing homes, use of masks, hygiene practices, and increased infections was observed in the notes of the meetings of technical committees during the management of the pandemic.

Certain texts also mentioned aspects that may be linked to the importance of participation in addressing disinformation, indicating the role of community workers, civil society and medical professionals. The role of international organisations was also mentioned.

“Finally, they addressed the challenges of communication in the post-pandemic framework and the role of international public health organisations in counteracting disinformation and fake news”(Excerpt from the minutes of a meeting of international leading figures on mental health, 2022, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/vizzotti-se-reunio-en-washington-dc-con-el-director-general-de-la-oms-para-dialogar-sobre. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

In most of the texts from both countries, the focus on disinformation was linked to COVID-19. However, disinformation was also linked to other health issues. In the case of Argentina, sentences related to the post-pandemic situation, SRH, mental health, organ donation, HIV, violence, and smoking were observed; and in Spain, references to Alzheimer’s, SRH, child violence and alcohol consumption.

Noteworthy phrases related to disinformation on organ donation issues were found in texts from Argentina, such as avoiding “the resurgence of old myths”. Regarding sexual violence and disinformation, the importance of providing health teams with training on this issue was noted in Spain.

“The minister has emphasised that there is still a high degree of disinformation regarding Alzheimer’s, “misconceptions about the disease, false beliefs and claims that lack scientific rigour”. For example, it has been explained that Alzheimer’s “is a disease, not an inevitable consequence of ageing”(Excerpt from a working paper on the campaign to raise awareness of Alzheimer’s disease, 2019, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=4671. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

In the category of groups of interest, some excerpts drew distinctions between disinformation/communication for children or adolescents. In Argentina, disinformation was linked to smoking amongst the youth, and in Spain, to alcohol consumption. Additionally, observations on the role of the media and ideas related to healthy habits in childhood and healthy ageing were also detected in the case of Spain.

“…has meant the importance of promoting healthy lifestyle habits, such as physical exercise, healthy diets, or the creation and rehabilitation of spaces focused on promoting childhood or healthy ageing”(Excerpt from a working paper on the media’s role in disease prevention and promoting good health, 2023, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=6268. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

In both countries under analysis, and especially during the pandemic, ideas related to the category of human rights linked to disinformation were found. In the case of Argentina, the following elements were mentioned in addition to disinformation: the importance of a bioethical analysis, human rights, the right to information, conflicts of interest and the protection of sensitive health information. Additionally, phrases focusing on communication from a rights-based perspective and indicating that disinformation and prejudice are one of the main barriers, have also been observed in Argentinian mental health documents. In Spain, the objective of protecting citizens’ right to health from hoaxes and fake news was highlighted.

In both cases, the problem of disinformation is located within a cultural context. In Argentina, the term “cultural effect” produced by fake news is used, and the promotion of a culture of prevention is mentioned in Spain

“For specialists, the different dilemmas that arise in the current context and which should be discussed from the perspective of bioethics and human rights are centred on the following key aspects: public policies versus individual rights and freedoms; pandemic versus critical resources; infodemic versus the right to information; use of sensitive personal data versus the right to privacy, and discrimination versus the recognition of vulnerable groups”(Excerpt from a working paper of the Bioethics and Human Rights Committee during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/gonzalez-garcia-destaco-trabajo-del-comite-de-bioetica-y-derechos-humanos-por-covid-19. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

- 2.

- Dimension. Gender and intersectionality

In the fragments on disinformation in the analysed documents from Argentina and Spain, it was observed that in both cases more than 32% of the documents used gender binary language (Table 3).

Another interesting result is that, of the total number of health-related documents analysed, 69.6% did not make a distinction based on vulnerable groups (i.e., They took a general approach). The small proportion of documents that did make any distinctions (30.4%) included women, children, adolescents, LGBTQ+ groups, ethnic and racial minorities, socially vulnerable populations, older people, people in war contexts, people with chronic diseases or disabilities, in relation to different health problems.

Table 4 displays the absolute frequency of codes for vulnerable groups.

Table 4.

Absolute frequency of codes for vulnerable, by country (n = 102).

Table 5 displays disinformation/infodemic frequencies according to gender. Binary gender approach was predominant in the pooled data and the subgroups (countries), both for disinformation and infodemics and other related categories.

Table 5.

Frequency distribution of disinformation/infodemics according to gender, by country (n = 102).

- 3.

- Dimension. Social determinants of health

Upon applying the WHO framework of social determinants of health (Table 2) which includes structural determinants (such as income, education, occupation, social class, gender/sex or race/ethnicity) and intermediate determinants (material circumstances, psychosocial, behavioural and/or biological and health system factors) to the analysis of the fragments on health disinformation, it was found that most of them were barely present.

However, an exception was observed in the gender/sex category within the structural determinants of health (Table 2). Gender was linked to aspects of diversity in texts from both countries. For example, in the case of Argentina, the following excerpt demonstrates the existence of violence linked to disinformation on HIV and this has a greater impact on vulnerable groups, especially sexually, ethnically, and racially diverse individuals.

“The stories included in the survey reveal different types of violence present in institutional and private settings that mark a pattern of disinformation and ignorance regarding HIV, its nature and behaviour. According to the study, the populations most affected by these causes are trans women (18%), women from indigenous tribes (54%) and internal migrant women (48%)”(Excerpt from a scientific report on Stigma and discrimination towards persons with HIV, 2021, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/estudio-sobre-estigma-y-discriminacion-hacia-las-personas-con-vih-en-el-pais. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

Situations of digital violence linked to gender and disinformation were also mentioned in texts from Argentina. The same elements applied to digital violence against political leaders who are women are observed in the following excerpt.

“There, the official especially stressed the links between digital violence and political violence which may give rise to and/or contribute to the generation of hate speech. Indeed, she considered that “violence and harassment in these cases are directed against women leaders because they are women”, and not just because of their opinions or the policies they pursue. Thus, women in politics become targets of hate speech and violence, as well as disinformation and smear campaigns”(Excerpt from a working paper on the country position at the 67th session of the Commission on the Legal and Social Status of Women (CSW), 2023, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/el-mmgyd-represento-la-posicion-argentina-ante-la-csw-repudio-la-violencia-politica-y-pidio. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

The presence of the social class category (socially vulnerable groups) together with disinformation on health issues was observed in texts from both Argentina and Spain. However, this category was also partly linked to gender, especially in terms of sexual and reproductive health, as shown below.

“But what about the adults who did not receive it? How was their sexual education? In most cases, sexual education was either non-existent or limited to reproduction, always following concepts of binary gender, romantic love, and heterosexuality. Thus, many generations grew up with silence, taboos, and disinformation”(Excerpt from a document on the implementation of comprehensive sex education on public television, 2023, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/television-publica-estrena-sin-filtro-esi-para-adultxs. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

“Gender inequality, poverty, lower levels of education hinder women’s capacity to act and result in disinformation regarding contraception”(Excerpt from a document on the implementation of a guide on Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy, IVE, 2022, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/Guia_IVE_Farmacologica_04-11-2022.pdf. Accessed on 21 July 2024)

Within the social class category, in the case of Argentina, aspects were also found which indicate that fake news on socially vulnerable groups (residents of informal housing) contribute to the reproduction of negative stereotypes and stigmatisation of these groups.

“Fake News regarding the Villa Azul neighbourhood in Quilmes is contributing to the generation of stereotypes and possible stigmatisation of low-income groups. Within the context of this pandemic, information must be treated with the utmost responsibility and care so as not to continue fostering a negative view of historically vulnerable groups”(Excerpt from a working paper on fake news during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/fake-news-en-contexto-de-covid-19. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

Meanwhile, texts from Spain included phrases pointing to the difficulties faced by rural populations in accessing Alzheimer’s care, in connection to the low levels of information and health education on this disease.

“People lack information and health education on the characteristics and importance of the first symptoms. This is especially true in rural areas. It can take users between one and two years to seek medical care. There may be an excessive tendency to interpret early symptoms as age-related changes rather than as manifestations of disease. The euphemism “senile dementia” is still used too often”(Excerpt from a document on the Comprehensive Plan on Alzheimer’s and other Dementias, 2019, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/docs/Plan_Integral_Alhzeimer_Octubre_2019.pdf. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

Links have been detected between interculturality category, gender, and disinformation. The following excerpt from a document from Argentina shows how disinformation can exacerbate fear in victims of violence, highlighting the importance of including an intercultural perspective. The important role played by the State when intervening in these situations is also highlighted.

“Some common reflections were on the importance of coordination at National, Provincial and Municipal levels, the deconstruction of stereotypes and prejudices when making an intervention, taking into account and working on the fear felt by many victims due to disinformation, taking advantage of the mechanisms available to the ministry for accompaniment and assistance, the importance of incorporating an inter-cultural perspective in cases of indigenous and migrant people, and the need to generate empathy towards the victims by their circle of trust and the state agents who must intervene in the situation, the importance of incorporating intercultural perspectives in cases of indigenous people and migrants, and the need for empathy towards the victims by their circle of trust and intervening state agents”(Excerpt from a meeting on the intersectional approach to gender-based violence, 2020, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/realizamos-el-taller-miradas-y-acciones-para-el-abordaje-integral-de-situaciones-de-0. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

Intermediate social determinants were present to a limited extent in both cases analysed, mainly in relation to the health system category. Phrases that indicated the role of health teams in building trust, informing, and combating disinformation, especially in health crisis contexts, were detected.

“Information from health professionals and the WHO continues to be the most trusted, and again, people have little confidence in social media, the internet and talk shows. In any case, the institutions that generate the most confidence remain unchanged: the scientific and health community continues to be foremost”(Excerpt from a working paper on COSMO-Spain, concerns regarding the pandemic and confidence in vaccines, 2021, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=5225. Accessed on 18 July 2024)

Elements related to the importance of community work to combat disinformation, especially on COVID-19 vaccines, were also found in some texts. These ideas are observed in the following excerpts.

“…It was considered that “to combat disinformation regarding the Covid-19 vaccination campaign, it is essential to train neighbourhood advocates to support the campaign on the ground”(Excerpt from a training document for community advocates of vaccination, 2021, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/comenzo-pensemos-en-vacunas-el-ciclo-de-capacitaciones-virtuales-para-promotores-y. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

- 4.

- Dimension. Environmental determinants of health

On analysing disinformation from the perspective of environmental determinants of health (which includes water, sanitation and hygiene, air quality, chemical safety, and climate action) (Table 2), a significant information gap was observed. Fragments were found in only two documents, whose scope was very limited.

The first case detected consisted of the statements made within the framework of the Global Summit on Climate and Health held in Spain. The participation of representatives from different sectors, including the government, was noted. The need to promote research on mental health linked to climate change and to counteract disinformation was highlighted. These ideas clearly demonstrate a link between health, disinformation, and environmental determinants.

“…that further research on mental disorders linked to climate change is required as well as counteracting disinformation by defending activists in their fight to preserve the planet”(Excerpt from a working paper on the Global Summit on Climate and Health, no date, Spain. URL: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/cop25/agenda/docs/7_de_diciembre_Global_Climate_Health_Summit_Resumen_Jornada.pdf. Accessed on 19 July 2024)

The other case was a publication from Argentina related to the screening of documentaries that seek to raise awareness and combat disinformation and myths surrounding the impact of plastic use around the world and its associated problems, such as the climate crisis, environmental justice, and public health.

“TECtv—the channel of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation—will broadcast a 3-episode investigative documentary series called Why Plastic? Its goal is to raise awareness and fight disinformation by taking a closer look at the realities and myths surrounding the impact of plastic use around the world. The documentaries, produced by The Why Foundation and loaned for their regional première on this special date by the Latin American Television Network (TAL), seek to education citizens and trigger a debate on plastic pollution and its associated problems such as the climate crisis, environmental justice and public health”(Excerpt about a documentary presented by TECtv, 2022, Argentina. URL: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/tectv-presenta-tres-documentales-para-concientizar-sobre-el-uso-del-plastico-en-el-mundo. Accessed on 17 July 2024)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Results

Based on the comparative analysis of public documents from two countries (Argentina and Spain), it was found that several government health initiatives have included the topic of disinformation within the last three decades; however, this inclusion was of a limited nature.

Health issues addressed alongside disinformation in both countries under analysis consisted mainly of the COVID-19 pandemic (and vaccination). Some differences were found in certain “document type” categories; however, no marked differences were found in the dimensions and main categories analysed.

In both cases, limitations were observed in terms of the gender-based approach when addressing public health disinformation, which is in line with previous international scientific literature in health policymaking (Williams et al. 2021). These limitations were further compounded upon the inclusion of social and environmental determinants of health. It is worth pointing out that rapidly generated disinformation or information overload during a health or environmental crisis is also influenced by these categories and has social and health repercussions (Do Nascimento et al. 2022).

4.2. Comparison with Other Studies

From a historical perspective, quantitative data showed that public documents addressing disinformation on health issues had already existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, although at an incipient stage. This “pattern” of publication on the subject in different periods of analysis (before, during and after the pandemic) was observed in a similar way in both cases under analysis.

Differences in health issues linked to disinformation were also found in the periods before and during the pandemic. For example, prior to the pandemic, disinformation was mainly linked to chronic health issues and during the pandemic it was linked to COVID-19 and vaccines. These differences were similarly found in reviews that addressed disinformation (in general) and health disinformation (in specific) and its links to gender (Alcantara and Valentim 2023; Moyano et al. 2024).

Another difference found between the different analysis periods was the consideration of infodemics, noting that this concept emerged during the pandemic. This may be due, in part, to the WHO’s call during the World Health Assembly in May 2020 on the COVID-19 response, where infodemic management was recognised as a critical part of pandemic control.

It is worth noting that most of the documents focusing on disinformation and infodemics were published during the COVID-19 pandemic; mainly addressed this health issue (and others to a much lesser degree); and did not fully include gender, social and environmental determinants, and approaches. While addressing disinformation during a health crisis is significant, the lack of perspectives on other related aspects and determinants may be partly explained by the so-called “tyranny of the urgent”, where there is a gap between immediate biomedical or health requirements and others that are not deemed a priority, such as inequalities and structural problems (Smith 2019).

However, the social and environmental determinants of health are internationally recognised and are part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (WHO 2010; United Nations n.d.c).

Results on limitations in the inclusion of gender and environmental aspects are similar to those of another study of international climate change policy documents that revealed little gender mainstreaming in the Paris Agreement and none in the EU’s European Green Pact (Löcherbach 2022).

The public agenda on health disinformation must be linked to the environment and to social and gender inequalities. This is crucial, as we are currently facing the march of the extreme right in different regions of the world, especially in Latin America and Europe (Arroyo Menéndez and González 2020).

The interplay between right-wing politics and climate change denialism (along with other social aspects) has been reported in the scientific literature. These relationships may adopt different forms; for example, a current study suggests that socio-economic attitudes (characteristic of the mainstream right), exclusionary socio-cultural attitudes (including anti-feminist attitudes) and institutional distrust are predictors of climate change denialism (Jylhä et al. 2020).

Extremist groups have been observed to exploit disinformation for recruitment and legitimisation purposes during the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO 2024).

Another aspect to note is that, in both countries, regulations and evaluation regarding disinformation were poorly presented, which may be related to the presence of a weak “evaluation culture” in the area of health, both broadly and more specifically (health communication). This result may be linked to a study from Türkiye, which showed that while the goal of incorporating social as well as legal aspects in climate change adaptation policies was recognised, there was a lack of specific actions or tools for evaluation (Williams et al. 2022). As observed, the focus on disinformation in the public agendas of the cases under analysis decreased even more following the health emergency.

With regard to gender and as our work has shown, gender binary language was predominantly used. In terms of intersectionality, vulnerable groups (such as women, the elderly, children, adolescents, people of sexual, ethnic/racial diversity, socially vulnerable and disabled people) were practically absent. This is critical for at least two reasons. On one hand, these are the groups that most likely to be affected by misinformation, and it is necessary to include preventing infodemics by reducing risk factors in this vulnerable communities (Ishizumi et al. 2024); and on the other hand, in crisis contexts it is vital to communicate in a way that mitigates disinformation through an inclusive communication of risks that builds resilience (Khan et al. 2022).

Similar to our findings, previous studies in the Latin American and Caribbean Region (Moyano and Mendivil 2021; Haraki 2021) have demonstrated how governments included infodemics to a limited degree during the pandemic.

Another study conducted in Spain and Latin American countries (López-Pujalte and Nuño-Moral 2020) showed that 28% of the disinformation picked up by different media during the pandemic was from a known source, and 5% from individuals in important roles (such as heads and members of government).

Misinformation generated by top political leaders was also present in other countries and regions of the world (Pomeranz and Schwid 2021). As noted in a previous review, different situations of uncertainty arise within a health crisis context, which may lead to poor messaging from health officials and suboptimal communication skills (Su et al. 2022).

Based on our findings from two case studies located on different continents and the available scientific literature on the topic, it may be suggested that poor addressing of health disinformation and approaches to it via public initiatives is framed within a broader geopolitical context on a global scale. However, further studies are required for a more in-depth exploration of these aspects and their dimensions.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Some of the limitations of this study are due to its methodology, as it was involved only two case studies of national ministries of health. To our knowledge, this study has few or no precedents. This study adopts an innovative approach and may be of interest in different disciplinary areas (environment, health, communication, social and political sciences).

The analysis of specific cases of public action on environment, health and social inclusion is crucial to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations n.d.c). This is especially true for SDGs 3, 6, 7, 11, 12 and 13.

Another limitation may be due to possible reporting biases. It is possible that the search method has failed to detect some documents although, as mentioned, different measurements and validations were taken during data collection.

The “ephemeral” nature of information in virtual environments is also a limitation (Zorrilla-Muñoz et al. 2024). Different measures were taken in order to mitigate this consideration, such as reviewing all links at three different times and downloading all documents during the fieldwork stage. It should be noted that checking the links revealed that that they were all functioning, thereby demonstrating a degree of information stability on government websites.

Information other than that published by government agencies may also exist; therefore future studies should consider applying other data collection strategies and techniques (e.g., requesting information from the government agency or interviewing government agents responsible for these policies). However, the type of information found in both countries is consistent.

4.4. Recommendations

4.4.1. Health Communication Policies

Health communication policies may be improved in both countries by focusing on disinformation and infodemics. As observed in government documents (especially during the COVID-19 health emergency), although disinformation was placed at the centre of the political agenda, it was not included within an institutional hierarchy or policy as such. This indicates a divide between the objective and discursive elements of the problem, despite the fact that agencies called for action against infodemics during the pandemic (WHO n.d.; Tangcharoensathien et al. 2020). In other words, during the crisis, disinformation acquired not only a national but also an international dimension.

There is a need to reinforce health ministry websites against disinformation (with up-to-date and accessible information). This may be a feasible venture, given that both countries had implemented initiatives during the pandemic, although document generation dropped significantly after 2021. New actions must also be designed from more inclusive approaches.

4.4.2. Research

While the scope of this work was limited to health issues, the implementation of broad and sensitive search strategies enabled the detection of disinformation in other areas (such as hate speech, media, fake news on political issues, responsible use of technology, privacy, stereotypes, symbolic and political violence, access to public information, finance and economy, elections, digital divide, inclusive digital society, denialism, war contexts, public opinion, press freedom, business through social networks, and consumer advocacy), which are worth exploring in future studies.

The conceptual framework proposed in this paper may be used, albeit with modifications, in future studies and when designing and assessing public disinformation initiatives in both health and socio-environmental crisis contexts. This is especially important, given that disease outbreaks and extreme weather and climate events are currently occurring in different continents all around the world.

4.4.3. Evaluation

Very few complete and partial documents on the evaluation of disinformation were found, suggesting the need to extend searches to the provincial and municipal levels (via evaluations and meta-evaluations).

Reports from international organisations, NGOs, media, social networks, and private institutions were not included in this work; therefore, additional searches and specific websites must be consulted in order to expand the scope of the issue.

This work compiled information on and compared disinformation initiatives in both countries at different points, which may serve as a starting point for the active monitoring of information transparency, although further analysis is required in terms of this recommendation.

It is concluded that health disinformation was present in public initiatives in Argentina and Spain prior to, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there were limitations in various aspects: the problem was strongly linked to the health emergency, and appeared in a complementary fashion within public initiatives, without acquiring greater importance. Moreover, the inclusion of holistic approaches (gender, vulnerable groups, social and environmental determinants) was limited.

It may therefore be suggested that urgent measures are required to reduce the numerous gaps detected in public initiatives, within the field of the interdisciplinary study of health disinformation from a holistic perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.M., M.S.A.-T. and M.A.-M.; methodology, D.L.M., M.S.A.-T. and M.A.-M.; validation, D.L.M., M.S.A.-T. and M.A.-M.; formal analysis, D.L.M. and M.A.-M.; investigation, D.L.M.; data curation, D.L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.M.; writing—review and editing, D.L.M., M.S.A.-T. and M.A.-M.; visualization, D.L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Complutense Sociology Institute for the Study of Contemporary Social Transformations (TRANSOC in Spanish) for providing the necessary resources to translate this paper into English. The University Institute of Gender Studies (IEG-UC3M in Spanish) for the institutional support provided to the first author via the research stay programme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Data Collection Instrument

Appendix A.1. English Version

- E-mail

- CountryArgentinaSpain

- Website from where sourcedHealthLegislativeGoogleOthers (manual within primary documents)

- Name (title) of the document

- URL

- Document type (main)Policy/programme/interventionImplementationLegalWorkingScientificMediaOther

- Implementing authority (ministry) or publishing body

- Time of publication (year)

- Time of publicationPrior to the COVID-19 pandemicDuring the COVID-19 pandemicAfter the COVID-19 pandemic

- IncludedYesNo

- Grounds for exclusion

- Objective of the document (stated)

- Primary or secondary inclusion of communication/infodemic/disinformation in the textPrimarySecondary

- Context of applicationRuralUrbanBothNot reported

- Further information on region (rural/urban)

- Author’s gender (assigned by team)

- Whether: Official (government) documentPolicies or policy guidelinesSectoral strategies or strategies linked to specific health problemsOfficial statementsOfficial position papersSurvey reports or statistical publications or monitoring documents

- Further information if yes: Official (government) document

- Whether: Implementation DocumentTraining manuals or working toolsInterim or Final evaluation reportsFinancial analysisOperational plansProject/intervention proposalsApplications for funding

- Further information if yes: Implementation Document

- Whether: Legal DocumentLawsOther regulations (resolutions)Memoranda of UnderstandingCooperation agreementsLegislative notes

- Further information if yes: Legal Document

- Characteristics (Year of approval and regulation) If yes: Legal Document

- Whether: Working documentReports or minutes of meetingsMemorandaCommittee reportsPowerPoint presentationsDraft documentsMission reportsE-mails

- Further information if yes: Working document

- Whether: Scientific PaperScientific or peer-reviewed publicationsMaster’s or doctoral thesisTextbooks and other teaching materials

- Further information if yes: Scientific Paper

- Whether: MediaArticles in newspapers and magazinesPodcasts, videos and radio and TV segmentsAdvertisements and postersNewsletters, bulletins, mailing lists, blogs and websitesConversations on Twitter and other social media

- Further information if yes: Media

- Other documentsPromotional materialWarning and nutrition facts labels on food and other productsMedical or other health devicesPlans, architectural drawings, and maps

- Further information if Other documents

- Evaluation typeDesign: DiagnosisProcesses: Utilisation, ParticipatoryResults: Objectives-basedOtherNot stated

- Further information on evaluation type

- Budget (allocated and implemented)

- Definition of evaluation indicators (defined)

- Definition of evaluation indicators (evaluated)

- Refers to Intersectoriality

- Refers to Stakeholder Coordination Mechanisms

- Refers to Mechanisms for monitoring policy implementation

- It refers to coordination with other areas of the State

- Main gender focus (language)BinaryInclusiveNot recognisedNeutral expressions

- Interest groupElderlyWomenChildren and adolescentsLGBTQ+ groupsEthnic and racial minoritiesSocially vulnerable populationDisabilityNot stated/or general approachPersons in war/refugee/migrant contextsPeople with chronic diseases

- Disinformation and infodemics (main focus)DisinformationInfodemicMisinformationFake newsOther

- Definition of the construct/infodemic disinformation

- Public health issuesPandemic, COVID-19COVID-19 VaccinationOther vaccinesMental healthSexual and reproductive healthOther infectious diseasesRisk factors and non-communicable diseasesLifestyle (nutrition, smoking, sedentary lifestyle)Other

- Definition of the construct/health

- Social (structural) determinantsSocial and political contextIncomeEducationOccupationSocial ClassGender/SexRace/ethnicityNo element observed

- Definition of the construct/structural determinants

- Social determinants (intermediate)Material circumstancesPsychosocial circumstancesBehavioural and/or biological factorsHealth systemNo element observed

- Definition of the construct/intermediate determinants

- Environmental determinantsWaterSanitation and hygieneAir qualityChemical safetyClimate actionNo element observedOther

- Definition of the construct/environmental determinants

- Other information

Appendix A.2. Spanish Version

- Correo

- PaísArgentinaEspaña

- Sitio web de donde es capturadoSaludLegislativoGoogleOtro (manual dentro de documentos primarios)

- Nombre (título) del documento

- Link

- Tipo de documento (principal)Política/programa/intervenciónImplementaciónLegalDe trabajoCientíficoMedio de comunicaciónOtro

- Autoridad de aplicación (ministerio) o desde donde se publica

- Temporalidad (año de publicación)

- TemporalidadAntes del COVID-19Durante el COVID-19Después del COVID-19

- Se incluyeSiNo

- Motivos de exclusión

- Objetivo del documento (declarado)

- Inclusión principal o secundaria de comunicación/infodemia/desinformación en el textoPrincipalSecundaria

- Contexto de aplicaciónRuralUrbanoAmbosNo reporta

- Mas información sobre territorialidad (rural urbana)

- Sexo de autoría (imputado por el equipo)

- Si es: Documento Oficial (de gobierno)Políticas o directrices políticasEstrategias sectoriales o sobre problemas sanitarios específicosDeclaraciones oficialesDocumentos oficiales de posiciónReporte de encuestas o publicaciones estadísticas o monitoreo

- Ampliar información Si es: Documento Oficial (de gobierno)

- Si es: Documento de ImplementaciónManuales de formación o herramientas de trabajoInformes de evaluaciones intermedias o FinalesAnálisis financierosPlanes operativosPropuestas de proyectos/intervenciónSolicitudes de financiación

- Ampliar información Si es: Documento de Implementación

- Si es: Documento LegalLeyesOtras normativas (resoluciones)Memorandos de acuerdoAcuerdos de cooperaciónNotas legislativas

- Ampliar información Si es: Documento Legal

- Características (Año de aprobación y reglamentación) Si es: Documento Legal

- Si es: Documento de trabajoInformes o actas de reunionesMemorándumsInformes de comitésPresentaciones PowerPointProyectos de documentosInformes de misiónCorreos electrónicos

- Ampliar información Si es: Documento de trabajo

- Si es: Documento de CientíficoPublicaciones científicas o revisadas por paresTesis de máster o doctoradoLibros de texto y otros materiales didácticos

- Ampliar información Si es: Documento de Científico

- Si es: Medios de comunicaciónArtículos en periódicos y revistasPodcasts, vídeos y segmentos de radio y televisiónAnuncios y cartelesBoletines informativos, boletines, listas de distribución, blogs y páginas webConversaciones en Twitter y otros medios sociales

- Ampliar información Si es: Medios de comunicación

- Otros documentosMaterial promocionalEtiquetas de advertencia y nutricionales en alimentos y otros productosDispositivos médicos u otros dispositivos sanitariosPlanos y mapas

- Ampliar información si es Otros documentos

- Tipo de evaluaciónDiseño: DiagnósticaProcesos: Utilización, ParticipativaResultado: Por objetivosOtraNo refiere

- Mas información sobre el tipo de evaluación

- Presupuesto (asignado y ejecutado)

- Definición de indicadores de evaluación (definidos)

- Definición de indicadores de evaluación (evaluados)

- Refiere a Intersectorialidad

- Refiere a Mecanismos de coordinación entre partes interesadas

- Refiere a Mecanismos de supervisión de la implementación de la política

- Refiere a articulación con otras áreas del Estado

- Enfoque principal de género (lenguaje)BinarioInclusivoNo se reconoceExpresiones neutras

- Grupo de interésPersonas mayoresMujeresNiños, niñas, adolescentescolectivos LGBTQ+Minorías étnicas y racialesPoblación con vulnerabilidad socialdiscapacidadNo refiere/o enfoque generalPersonas en contextos bélicos/refugiados/migrantesPersonas con enfermedades crónicas

- Desinformación e infodemia (enfoque principal)DesinformaciónInfodemiaInformación erróneaNoticias falsas/Fake newsOtro

- Definición del constructo/infodemia desinformación

- Temas de salud públicaPandemia, COVID-19Vacunación COVID-19Otras vacunasSalud mentalSalud sexual y reproductivaOtras enfermedades infecciosasFactores de riesgo y enfermedades no transmisiblesEstilo de vida (nutrición, tabaquismo, sedentarismo)Otras

- Definición del constructo/salud

- Determinantes sociales (estructurales)Contexto social y políticoIngresosEducaciónOcupaciónClase socialGénero/SexoRaza/etniaNo se observa ningún elemento

- Definición del constructo/determinantes estructurales

- Determinantes sociales (intermedios)Circunstancias materialesCircunstancias psicosocialesFactores conductuales y/o biológicosSistema sanitarioNo se observa ningún elemento

- Definición del constructo/determinantes intermedios

- Determinantes ambientalesAguaSaneamiento y la higieneCalidad del aireSeguridad químicaAcción por el climaNo se observa ningún elementoOtro

- Definición del constructo/determinantes ambientales

- Otra información

References

- Alcantara, Juliana, and Juliana Valentim. 2023. Gender-Based Disinformation: A scoping review of the literature, 2013–2023. Ex Aequo 48: 125–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, David, and Christopher J. Schneider. 2013. Ethnographic Content Analysis. In Qualitative Media Analysis, 2nd ed. Thousand Oak: SAGE Publications, Ltd., pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentinian Legal Information System (SAIJ). n.d. Available online: http://www.saij.gob.ar (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Arroyo Menéndez, Millán, and Igor Sádaba Rodríguez. 2012. Metodología de la Investigación Social: Técnicas Innovadoras y sus Aplicaciones. Madrid: SYNTHESIS. ISBN 978-84-9756-760-2. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo Menéndez, Millán, and Rodrigo Stumpf González. 2020. El avance de la extrema derecha en América Latina y Europa. Política y Sociedad 57: 641–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayos, Emilio Jorge, and Jésica Pla. 2021. Welfare and social class. Social inequality in comparative terms: United Kingdom, Spain and Argentina. Revista Española de Sociología (RES) 30: a57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbado, Devon W., Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Vickie M. Mays, and Barbara Tomlinson. 2013. Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 10: 303–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Sánchez, Carmen, Ángel Vizoso, and Xosé López-García. 2023. Fake News in the Post-COVID-19 Era? The Health Disinformation Agenda in Spain. Societies 13: 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, Volume 1989. Available online: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalglish, Sarah L., Hina Khalid, and Shannon A. McMahon. 2020. Document analysis in health policy research: The READ approach. Health Policy and Planning 35: 1424–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daume, Stefan. 2024. Online misinformation during extreme weather emergencies: Short-term information hazard or long-term influence on climate change perceptions? Environmental Research Communications 6: 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, Israel Junior Borges, Ana Beatriz Pizarro, Jussara M. Almeida, Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, Marcos André Gonçalves, Maria Björklund, and David Novillo-Ortiz. 2022. Infodemics and health misinformation: A systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 100: 544–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECLAC. 2022. Towards the Consolidation of a welfare state in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Future of Social Protection in an Era of Uncertainty. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/eventos/la-consolidacion-un-estado-bienestar-america-latina-caribe-futuro-la-proteccion-social-era (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Gamir-Ríos, José, and Raquel Tarullo. 2022. Characteristics of misinformation in social networks. Comparative study of news denounced as hoaxes in Argentina and Spain during 2020. Contratexto 37: 203–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraki, Cristianne Aparecida Costa. 2021. Estratégias adotadas na América do Sul para a gestão da infodemia da COVID-19. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 45: e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Zhiwen, Chuhan Wu, and Pier Luigi Sacco. 2023. Editorial: Public health policy and health communication challenges in the COVID-19 pandemic and infodemic. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1251503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, Debbie L., Michelle Sodipo, and Skyler D. Jackson. 2023. The intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: Demonstrating utility through application to the pre-vaccine U.S. COVID-19 policy response. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1040851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizumi, Atsuyoshi, Jessica Kolis, Neetu Abad, Dimitri Prybylski, Kathryn A Brookmeyer, Christopher Voegeli, Claire Wardle, and Howard Chiou. 2024. Beyond misinformation: Developing a public health prevention framework for managing information ecosystems. Lancet Public Health 9: e397–e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, Beatriz. 2008. De la evaluación clásica a la evaluación pluralista: Criterios para clasificar los distintos tipos de evaluación. EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de CienciasSociales 16: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, Kirsti M., Pontus Strimling, and Jens Rydgren. 2020. Climate Change Denial among Radical Right-Wing Supporters. Sustainability 12: 10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Shabana, Jyoti Mishra, Nova Ahmed, Chioma Daisy Onyige, Kuanhui Elaine Lin, Renard Siew, and Boon Han Lim. 2022. Risk communication and community engagement during COVID-19. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 74: 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löcherbach, Greta Karoline. 2022. Gender and Climate Change: An Analysis of Gender Mainstreaming in Contemporary Climate Change Policy Making. [Thesis]. University of Twente. Available online: https://purl.utwente.nl/essays/91922 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- López-Pujalte, Cristina, and María Victoria Nuño-Moral. 2020. The “infodemic” in the coronavirus crisis: Analysis of disinformation in Spain and Latin America. Revista Española de Documentación Científica 43: e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health of Argentina. n.d. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Moyano, Daniela, and Lina Lay Mendivil. 2021. Communication products for COVID-19 prevention promoted by governments Latin American and the Caribbean. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 45: e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, Daniela Luz, María Silveria Agulló-Tomás, and Vanessa Zorrilla-Muñoz. 2024. Género, infodemia y desinformación en salud. Revisión de alcance global, vacíos de conocimiento y recomendaciones. Global Health Promotion 31: 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Ruvalcaba, Mario Alfredo. 2006. Modelos y regímenes de bienestar social en una perspectiva comparativa: Europa, Estados Unidos y América Latina. Desacatos 21: 109–34. [Google Scholar]

- Official State Gazette Agency. n.d. Available online: https://www.boe.es/index.php?lang=en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- PAHO. n.d. Environmental Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/environmental-determinants-health (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Pomeranz, Jennifer L., and Aaron R. Schwid. 2021. Governmental actions to address COVID-19 misinformation. Journal of Public Health Policy 42: 201–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seytre, Bernard. 2020. Erroneous Communication Messages on COVID-19 in Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103: 587–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Julia. 2019. Overcoming the ‘tyranny of the urgent’: Integrating gender into disease outbreak preparedness and response. Gender and Development 27: 355–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish Ministry of Health. n.d. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Su, Zhaohui, Huan Zhang, Dean McDonnell, Junaid Ahmad, Ali Cheshmehzangi, and Changrong Yuan. 2022. Crisis communication strategies for health officials. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 796572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangcharoensathien, Viroj, Neville Calleja, Tim Nguyen, Tina Purnat, Marcelo D’Agostino, Sebastian Garcia-Saiso, Mark Landry, Arash Rashidian, Clayton Hamilton, Abdelhalim AbdAllah, and et al. 2020. Framework for Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Methods and Results of an Online. Crowdsourced WHO Technical Consultation. Journal of Medical Internet Researce 22: e19659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Allison, Peter Sainsbury, and Jonathan Craig. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppenberg-Pejcic, Deborah, Jane Noyes, Tomas Allen, Nyka Alexander, Marsha Vanderford, and Gaya Gamhewage. 2019. Emergency risk communication: Lessons learned from a rapid review of recent gray literature on Ebola Vander-ford M, Zika, and yellow fever. Health Communication 34: 437–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. 2020. Good Practices in Gender-Responsive Evaluations. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/06/good-practices-in-gender-responsive-evaluations (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- UN Women. n.d. Gender-Inclusive Language Guidelines Promoting Gender Equality through the Use of Language. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Gender-inclusive%20language/Guidelines-on-gender-inclusive-language-en.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- United Nations. n.d.a Climate Change. The Paris Agreement. What Is the Paris Agreement? Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 29 May 2024).