1. Introduction

The wave of Black protests in early twenty-first-century America calling for the removal of public memorials to soldiers and sympathizers of the Confederate States of America—visual homages to pro-slavery forces in the U.S. Civil War (1860–1865) who embraced White anti-Black violence and racial caste authoritarianism—surprised no one. Yet, the decision by the first Black woman mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina, to form a special commission in June 2020 to evaluate the city’s public memorials, and to make recommendations for dealing with said public memorials, took observers of Southern politics by surprise. Unlike other Black leaders across the country dealing with Confederate memorials, Mayor Lyles did not call for an immediate removal of the markers, did not remove the markers out of sight of the public, and did not send security officials to protect the markers. In addition, the mayor resisted constituent pressure calling for a unilateral decision to remove or retain said public memorials, and the mayor explicitly asked city residents to partake in a painful dialogue about whose political history and whose perspectives taxpayer-funded edifices should venerate. In short, by establishing the Charlotte Legacy Commission [hereafter the Charlotte Commission], the mayor asked city residents to confront (and hopefully resolve) long-simmering tensions—directly, systematically, and publicly—around race relations, cultural memory, and monumentality as those tensions informed the city’s projected image as an exemplar of the “New South” (

Hanchett 2020).

Our aim in this article is to examine local media reactions to the establishment and workings of the Charlotte Legacy Commission, created to investigate and make recommendations about the city’s taxpayer-supported Confederate memorials, and to examine the ways in which the commission dealt with related tensions surrounding socioeconomic, political, and demographic change and monumentality in the city. We utilize a mixed methods “embedded design” case study approach (

Creswell and Plano Clark 2011) to collect quantitative and qualitative data on the context shaping the inauguration of, actions of, and constituent reaction to the commission. Specifically, we analyze statewide survey data, commission materials, and two years of articles from

The Charlotte Observer and

The Raleigh News & Observer. Our research also briefly engages scholarship on heritage claims, monumentality, cultural memory, and electoral representation to situate the Charlotte Legacy Commission within larger theories of government response to constituent demands. On multiple levels, the mayor’s decision to form the Charlotte Commission was not as unpredictable as one might have thought. In one way, the formation of the Charlotte Commission seemed consistent with the theory of responsive government. As North Carolina’s most populus city and the self-proclaimed “international gateway to the South”, the city of Charlotte had a rich history of challenging venerations of racial caste authoritarianism and anti-Black violence. By 2020, the city of Charlotte had weathered almost two decades of socioracial demographic shifts in the region and had launched a series of successful campaigns to attract financial institutions to the city. Indeed, various groups had tacitly embraced the motif that the city of Charlotte evidenced a “New South” approach to intergroup relations and governance, whereby economic co-dependence mitigated racial antagonisms and propelled infrastructure growth and cultural inclusion. To that effect, unlike other Southern cities experiencing upheaval around the Confederate monument question during the 2019–2020 period, the city of Charlotte did not have prominent displays in public spaces that pro-removal activists could easily target for defacing or that pro-retention activists could use as rallying sites. In fact, decades before the 2019–2020 period, then-Assistant City Manager Lyles worked with a biracial coalition of Charlotte political and administrative leaders to move all Confederate statues to “a [historic] cemetery that was for Confederate soldiers that had died in the line of duty”.

1 Markers were erected to designate the commemoration and to provide information to viewers about who was buried at the sites. (The cemetery referred to is Elmwood Cemetery).

Charlotte was a Democratic-led city, even before its social demography had shifted more favorably toward non-White, liberal, immigrant residents. More importantly, numerous cities and county commissioners across the state of North Carolina had taken decisive action to remove Confederate monuments from public spaces (

Jasper 2020), actions which some asserted contravened a 2015 law banning the removal, relocation, or alteration of state-owned monuments “in any way without the approval of the North Carolina Historical Commission”.

2 Vandalism against Confederate monuments in 2015 forced the city of Charlotte to take additional action in ways that met the letter of the 2015 law and which could satisfy stakeholders.

3 Compared to doing nothing, Mayor Lyle’s 2020 actions to form the Charlotte Commission were a step toward what most Democratic partisans wanted. Furthermore, the world had witnessed a new wave of Black Lives Matter-inspired protests challenging authoritarianism, racial oppression, and police brutality in May of 2020, following the death of George Floyd at the hands of police.

Given these considerations, on the surface, the mayor’s decision to form the Charlotte Commission seemed like an uncontroversial response to a salient issue. Having said that, however, the formation of the Charlotte Commission also seemed inconsistent with the theory of responsive government. The special information-gathering body was established years after the U.S. had witnessed a spike in the activities of White supremacist organizations following the 2016 election of Donald Trump, and well after non-governmental organizations, both inside and outside of the United States, had noted the global rise in right-wing populism, the erosion of public support for democratic norms, and the relationship between interracial clashes and the public veneration of figures supporting racial caste authoritarianism (

Forest and Johnson 2019). Thus, the mayor established the Charlotte Commission almost three years

after the deadly August 2017 “Unite the Right” White supremacist and Neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, VA, who had gathered “to protest the [city’s] planned removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee” (

Heim et al. 2017). The Charlotte Commission also came almost two years after protesters, in August 2018, toppled the infamous Confederate Monument the “Silent Sam” statue at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a site of protest only hours away from Charlotte by automobile.

4 For some observers, the mayor’s decision to form the Charlotte Commission provided little relief to Black residents who had to see homages to White supremacy in their everyday travels across this “New South” city—especially when other Black mayors in the South had acted quickly to remove said figures from the public eye. On balance, residents could not easily categorize the mayor’s actions as responsive or as unresponsive.

Indeed, we assert that it is precisely because Mayor Lyles—Charlotte’s first Black woman mayor in the office’s 164 years of existence—took a decidedly different path to addressing the controversy about Confederate memorials than did her mayoral contemporaries that further scrutiny of the Charlotte Commission and public response to its establishment is justified. The creation of the Charlotte Legacy Commission was destined to channel larger tensions related to race relations, political power, cultural memory, and government response to White supremacy.

For instance, take these key themes related to Black political engagement with the “new politics of the Old South” (

Bullock and Rozell 2021;

White 2009): the emergence of a new cadre of Black political leaders and a number of “historic firsts” in descriptive representation (

Carrington and Strother 2021;

Orey et al. 2021;

M. J. Price 2020;

Simien 2015,

2022); the demographic changes termed the “browning of the New South” (

Jones 2019); the cultural impact of monuments or “monumentality” (

Rigney 2008); and the obligation of Black leaders to address demands for accountability from a new generation of Black activists. In that regard, our research on public reactions to the controversy over Confederate memorials in Charlotte and to the Charlotte Legacy Commission fills a gap in scholarship on the “new” governance styles of twenty-first-century Black officialdom (

Gillespie 2012), especially the scholarship on the wave of early twenty-first-century Black women mayors of demographically diverse urban centers (

Austin 2023).

In other words, our decision to examine Mayor Lyles and the Charlotte Legacy Commission as a case study reflects its relative uniqueness in examinations of Black responses to public homages to White authoritarianism in the Southern United States. Mayor Lyles and the Legacy Commission leveraged the controversy about Confederate memorials in the city to encourage more conversations about the role of race in shaping America’s past, present, and future. Other Black women mayors at that time did not establish similar pathways for their constituents to study the underlying issues and to drive government action about public memorials to the Confederacy. As such, we assert, this single case study on Charlotte presents a rare opportunity to excavate connections across the literature examining Black women’s leadership, government accountability, the racialization of public space, cultural memory, and Confederate monumentality in the American South.

2. Heir Disputes, “Historic Firsts”, and Confederate Memorials in Charlotte

Numerous studies have documented the impact of sociodemographic change on the rise of right-wing populism and authoritarian leadership (

Altemeyer 1996;

Bai and Federico 2021;

Duckitt and Farre 1994;

Górska et al. 2022;

Schaller and Waldman 2024). These studies detail how and why certain groups react negatively to changes in the ethno-racial composition of their surroundings as “existential threats”, and how and why violence often follows perceived or actual changes in the aggrieved group’s economic circumstances, social status, or political influence. Animated by hostility to the outgroups’ presence and disenchantment over public policies deemed unnecessarily favorable to the outgroups, aggrieved ingroup members often embrace leaders espousing authoritarianism and vowing to return said ingroup to prominence relative to the racially or ethnically different outgroups (

Stenner 2005). By leveraging electoral democracy to support illiberal aims, these aggrieved ingroups exploit cultural clashes and economic angst to enact or strengthen exclusionary policies and social stratification. Because monuments are cultural markers and signifiers of political events, they are also the sites of physical and epistemological struggle between ingroups and outgroups over whose histories should be celebrated and whose social values should drive policy. In Europe, for instance, the resurgence of right-wing authoritarianism has surprised many onlookers. In the American context, multiple organizations, like the Southern Poverty Law Center, charted the increase in the number of anti-government groups and White hate groups following the 2008 presidential election of Democratic Illinois U.S. Senator Barack Obama and following the 2016 presidential election of Republican Donald Trump. Scholars accept that the post-2008 growth in White supremacist activity in America is connected to White anxiety about the “Browning” of the country, a phenomenon tied to sociodemographic shifts in the country due to ethno-racial differences in fertility rates, marriage rates, mortality rates, and state-to-state outmigration patterns.

Equally insightful are other studies that connect sociodemographic shifts in society to the rise in enthusiasm and feelings of hopefulness amongst ingroup and outgroup members who see new possibilities for electoral coalitions and political inclusiveness. These studies showcase how ingroup members work to incorporate members of the culturally and racially distinct outgroup into the existing socioeconomic/political opportunity infrastructure, rather than oppose the latter’s integration. Whether motivated primarily by compassion, enmity, altruism, or self-preservation, members of the ingroup leverage their influence to promote and to mandate outgroup acculturation, assimilation, and integration. Consequently, an ethnically heterogenous society can swing between periods of intergroup violence to periods of intergroup cooperation, of intergroup economic co-dependency, and of outgroup submission, as both ingroup and outgroup members vary widely in their reactions to the pace at which the latter group embraces incorporation into the former group.

The renewed debate in twenty-first-century America over the removal of Confederate monuments channeled longstanding tensions about Whiteness, cultural memory, national identity, and partisanship in the country (

Hutchings et al. 2010;

Johnson et al. 2019;

Orey et al. 2021;

Schaller 2006;

Schaller and Waldman 2024). And, as such, that debate is an archetypical example about the ways in which sociodemographic changes can reenergize longstanding attitudinal, partisan, and experiential cleavages concerning political inclusiveness (

Benjamin et al. 2020;

Evans and Lees 2021). Rather than revisit the voluminous literature examining public reactions to the removal or retention of Confederate memorials, here we summarize certain contributions of that literature to excavate their relevance to the debate over how government actors and citizens should respond to demographic shifts. As stated by

Osborne (

2014, p. 3), “monument and monumentality are closely related, but distinct phenomena”. The latter is best conceptualized as “an ongoing, constantly renegotiated

relationship between thing and person, between the monument(s) and the person(s) experiencing the monument”. As such, any monument at any particular time will resonate differently across members of any particular group. In other words, as

Rigney (

2008, p. 346) states, “the canon of memory sites with which a community identifies is regularly subject to revision by groups who seek to replace, supplement, or revise dominant representations of the past as a way of asserting their own identity”. Thus, one cannot separate the opposition of White supremacist groups to the removal of Confederate monuments from their racial identity as Whites and from their support of racial caste authoritarianism. Drawing upon a litany of research in history, memory studies, and religious studies,

Darrius Hills (

2023, p. 49) summarily encapsulates this point when remarking, “Contemporary White nationalist fervor around the preservation and defense of Confederate material culture—statues, monuments, and landmarks—can be explained through the concept of totemism as a trope for religious life and activity, and as a feature of collective racial identity formation”.

Hills (

2023, p. 49) continues: “White nationalists’ zeal to preserve Confederate sites enables a transformation of Confederate material space from the realm of the ordinary toward a new functionality as racial holy sites around which White nationalists strengthen, reconsolidate, and reaffirm group identity”. In other words, given the “relational approach [embedded in to the study of] monumentality” (

Osborne 2014), one must recognize the significance of said material culture to identity maintenance practices. As such, White supremacists theorize the state-sanctioned removal of said pieces of material culture from public space as tantamount to state-sanctioned anti-religious violence to thwart the public veneration of the South’s “sacred history” (

Hills 2023;

Mathews 2018) of sacrifice against the (evil) aggressive North.

In that regard, “The Lost Cause” narrative, as a heuristic device, emboldens an emotive and cognitive pro-White supremacy orientation that interprets the removal of “Confederate material culture” from the public square as a deeply troubling conundrum of epic social, epistemological, religious, and political importance in the context of shifting electorate predilections (

Autry 2019;

Carr 2021;

Hills 2023;

Pollard [1866] 1994;

Reich 2020). The counter-narrative, of course, has a two-fold argument: first, that Southern Successionists were motivated by anti-Black racial animus, by a desire to perpetuate the enslavement of Africans/African Americans, and by a mythological understanding of the U.S. Constitution in which state interests/desires unequivocally eclipse national interests/desires across all policy domains and across all time periods; and second, that Southern Successionists were traitors to the nation state, were defeated in battle, and were reincorporated into the nation state body politic. In underscoring the differential power of language,

Hills (

2023, p. 52) notes that the “Lost Cause mythology is an adaptive and expressive feature of southern culture rooted in a distinctive religio-political response to perceived interference from ideological, regional, and political reforms thought to stifle southern peoplehood”.

Building upon the work of

Osborne (

2014),

Hills (

2023), and

Rigney (

2008), we assert that treatments of Confederate memorials, viewed as totems of “southern peoplehood” (

Hills 2023) and as symbols of White supremacist efforts to re-establish and maintain anti-Black racial caste authoritarianism, should be theorized as visualized heir disputes. That is, we contend, these monuments represent contested claims over whose heirs (i.e., descendants) are entitled to inherit the intergenerational transfer of power and authority over the U.S. landscape. Because American White supremacists claim that the U.S. landscape belongs to Whites—as descendants of the Nordic Race divinely ordained to rule over so-called inferior racial groups (

Yang 2020)—public totems to White supremacy demarcate two things: a persistent dispute over inheritance rights, and a differentiation between Whites (as legal heirs) and non-Whites (as non-heirs). Moreover, as “sites of memory” and as “agents of memory” (

Vinitzky-Seroussi 2002), Confederate monuments and other aspects of Confederate material culture serve to socialize succeeding generations of Whites to believe that changes in the sociopolitical environment will not and cannot displace the power and privilege (

Etter 2001;

Evans and Lees 2021;

Johnson et al. 2019) afforded by their inheritance position and inheritance rights. Philosophically speaking, ultimately, whether these public “sites of memory” present visitors with a “multivocal commemoration” (

Vinitzky-Seroussi 2002) or with a “fragmented commemoration” (

Holyfield and Beacham 2011) is a secondary concern, for the mere existence of these edifices in public spaces should illuminate the primary concern: said monuments remind succeeding generations of Whites and non-Whites that disputes about their claims remain unsettled. In legal parlance, as artifacts symbolizing the will of a benefactor who bequeaths a particular benefit to an identified beneficiary, Confederate monuments in public spaces suggest that homages to anti-Black racial caste authoritarianism serve legitimate pedagogical, historical, epistemological, psychological, and social functions precisely because society can and should revisit the adjudication of heir disputes. In line with its existence as a majority-rule electoral democracy, Americans typically prefer that ballots resolve political heir disputes about cultural memory and the public veneration of historical figures.

Yet, it is also racial differences in the ways in which Americans understand electoral democracy that make the debate over removing Confederate memorials an evergreen conflict in the context of sociodemographic change and race relations. One aspect of the problem is Americans’ penchant for embracing the “populist” conceptualization of voting and democracy (c.f.

Riker 1988), whereby electoral majorities become the purveyors of the public will and the protectors of the so-called common good. Another aspect of the problem is that American history is replete with examples of Whites denying voting rights to ethnic and racial minorities (

Anderson 2019;

Guinier 1994) and castigating the latter’s preferences as out of step with the common good. Thus, if one follows the populist conception of the vote within the literature on democratic theory, intergroup conflict resolved through the ballot box would always reflect White majorities. There would be little incentive for Whites to change the public veneration of their heroes and heroines. But shifts in an area’s socioeconomic demography would change the public veneration of individuals, moments, and concepts if non-Whites controlled the political opportunity structure or if the political infrastructure was amenable to having multiple actors weigh in on the issue (

Johnson et al. 2019). Hence, the evergreen conflict in ethnically heterogeneous societies like America is the epistemological challenge associated with removing, retaining, and installing public displays that privilege either the prior sociodemographic landscape or the future landscape. Both Whites and non-Whites committed to majoritarian electoral politics see the next election cycle as their chance to change the public veneration of the Other. And because both groups pay close attention to the ways in which elected officials negotiate constituent demands for removal, retention, and installation, constituents rightfully envision their demands as consistent with symbolic representation and substantive representation.

2.1. Historic Firsts

The presumption that voting majorities should get their way on policy questions makes it especially difficult for “historic first” Black mayors (

Simien 2015,

2022), individuals who have broken the glass ceiling in their respective locales, to negotiate constituent demands for the removal and for the retention of Confederate monuments. Here, we summarize and draw upon two observations in the literature on race and representation [hereafter R&R literature] to illustrate why the Confederate monuments controversy might pose specific challenges for “historic firsts” mayoral leaders. First, the R&R literature demonstrates that officials respond to both inattentive publics and attentive publics, groups who hold both latent demands and expressed demands, in hopes of mitigating the likelihood of electoral backlash. Much of the forecasting that officials do (in anticipation of whether an issue will galvanize the public) relies heavily on analyses of issue saliency and of sociodemographic trends. Astute elites will also attempt to co-opt issue positions to shape the content and character of how issues are depicted and received by ingroup and outgroup members. Second, the R&R literature confirms that Black candidates overall, and Black women candidates most specifically, face an array of reputational challenges when trying to establish credibility in their acumen to represent non-Black constituents. For instance, Black candidates must thwart accusations of unfettered pro-Black (meaning anti-White) or pro-women (meaning anti-men) favoritism and must project an image that they share an ideological proximity to fellow party identifiers (

Brown 2014;

Brown and Lemi 2021;

Gay and Tate 1998). Regarding the latter, the literature on R&R suggests that attacks on Black officials for violating cultural expectations or for violating ideological expectations (e.g., expectations of Black racial solidarity politics) can be thought of as attacks on whether officials are proximate to the group’s centroid position on a public policy issue (

Wilson and Brown-Dean 2012). As such, the campaigns of non-traditional candidates can have a mobilization effect on

underrepresented communities and can have a mobilization effect on

overrepresented communities as the separate communities seek clarification on or seek repudiation of a candidate’s spatial location on a policy issue. It is therefore unsurprising that Black women officials face a “double bind” challenge (

Brown and Lemi 2021;

Gay and Tate 1998) of confronting expectations that their race, gender, or both ascriptive identities should or should not inform their governance style (or location of their position on policy questions).

To that, the R&R literature on “historic firsts” documents the extraordinary efforts that Black women politicians have had to make when dealing with the intersection of racism and sexism (

Brown and Lemi 2021;

Gay and Tate 1998;

Lemi and Brown 2019;

Simien 2015) as defining parameters of their positions on policy questions. Scholars have rightfully called attention to the various ways that cultural norms and formal institutions work to marginalize and delegitimize Black women officials, to curtail opportunities for Black women candidates to seek and win elected office (

Brown and Gershon 2016;

Brown and Lemi 2021), and to circumscribe the rhetorical and spatial freedom afforded to Black women officials seeking to build coalitions. Third, the R&R literature demonstrates that constituent expectations of campaign style and legislative style matter (

Bernhard and Sulking 2018;

Burge et al. 2020), and that said expectations are simultaneously racialized and gendered (

Brown and Gershon 2016). Thus, some inescapable truisms in American politics shape constituent and candidate actions: racialized expectations about the campaign and governance styles of Black leaders (

Baek and Landau 2011;

Stout 2015;

Wilson and Brown-Dean 2012); “dog whistle politics” and racial appeals (

Haney-López 2014;

McIlwain and Caliendo 2011;

Stephens-Dougan 2020;

Thompson and Busby 2023); and gendered expectations about the policy acumen and policy orientations of candidates (

Osborn 2012). In toto, the R&R literature underscores the challenges new “descriptive representatives” could face when negotiating constituent demands for the removal and for the retention of Confederate monuments: the local news media infrastructure and the previously dominant electoral coalition might be especially hostile to a “historic first” official. Either could manifest said hostility by (a) emphasizing the executive’s social identity as a driver of their policy actions, (b) characterizing the executive’s actions as pandering to a new demographic order, or (c) questioning the executive’s acumen to deliver government services.

While we acknowledge that these aforementioned challenges are and would be especially difficult for a “historic first” in any time period, we nonetheless assert that the 2019–2020 period in American politics posed specific challenges to Black leaders confronting the issue of monumentality in wake of the 2016 presidential election results, the global ascendancy of authoritarianism, and the right-wing populist challenge to pluralist democracy. As mentioned earlier, Black people had demanded that elected and appointed officials remove U.S. Confederate memorials from public spaces long before the 2019–2020 wave of protests, and the Black Lives Matter (BLM)-led/inspired protests of said memorials pre-dated the summer 2020 wave of anti-police brutality and anti-racism protests following the murder of George Floyd.

In that regard, Black agitation to deepen “universal freedom” and to further “institutionalize Black civil rights” (

Walton 1988) has always concerned itself with ending the racial privatization of public spaces. Right-wing populists and White supremacists oppose efforts to remove visual tributes to racial caste authoritarianism and to reform laws and customs that disfigure the racial order. Coupled with the BLM protests decrying anti-Black state-sanctioned and citizen-sanctioned violence (

Ransby 2018), the BLM protests at sites of taxpayer-funded Confederate memorials, especially the eventual 2018 toppling of Silent Sam, directly illustrated the symbiotic relationship between anti-Black attitudes, structural inequities in policy outputs, and anti-Black symbols. Hence, given the potency of generational divides in Black attitudes (

Philpot 2017;

M. T. Price 2016;

Tate 2010) and the emergence of the mass protest-oriented Movement for Black Lives, it was inevitable that many Blacks would push harder for Black elected officials to heed calls for the removal of public memorials to the Confederacy.

2.2. The Confederate Memorial Controversy in Charlotte

Given anti-monument actions in Chapel Hill, in Raleigh, and across the country, the city of Charlotte was not immune to the controversy over Confederate memorials. The city of Charlotte was important in many ways to the cultural, political, and economic eco-systems of North Carolina: it was the state’s most populous city; it was located in the state’s economically important and culturally rich Piedmont region; it was the county seat of affluent Mecklenburg County; and it was popularly known as one of the South’s cosmopolitan financial centers. Charlotte leaders also pointed to the city’s election of Black firsts, to its weathering of the old politics of the South, and to its potential for future import in the national conversation about regional economies and sustainable modern cities.

5We contend that Black demands driving the 2019–2020 Confederate Memorial Controversy in Charlotte were substantively distinct from prior activist moments in the city. Our assertion stems, in part, from an acknowledgment that the BLM mass movement, alongside the nation’s twenty-first-century demographic character, fundamentally altered the American “political opportunity structure” (

Meyer and Minkoff 2004;

White 2009) for activists and Black elected officials alike. That is, we assert that America’s New South “political opportunity structure” altered both the logic underlying demands for removal and the logic underlying the receptivity of elected officialdom to said demands. This new logic enabled proponents and opponents of Confederate memorials in Charlotte to engage in “partisan conflict extension” (

Hare 2022;

Layman et al. 2010) by enabling them to rhetorically frame Black-led government-sanctioned removal efforts as either inappropriate or appropriate markers of racial progress (

M. J. Price 2013) that reflected responsive party government. Supporters of removal pitched their efforts to secure removal as a step toward racial reconciliation or as a step toward desegregating taxpayer-funded public space by centering the sensibilities of America’s new demographic. Opponents of removal pitched their opposition as bulkheads against historical amnesia, against the erasure of White Southern history, and against capitulation to “woke culture” and political correctness. Neither frame was an easy sell. According to

Hanchett (

2020), Charlotte was “the city that made busing work”, when schools were segregated and Black students were attending schools that were under-resourced. And, as journalists and other observers of life in Charlotte contended, the city was also a “tale of two cities” in which racism and discrimination shaped unequal access to economic opportunities.

In fact, a comparative analysis of select descriptive statistics about the United States, the city of Charlotte, and the state of North Carolina between 2000 and 2021 revealed much about how Charlotte could become one of the sites of conflict over Confederate memorials in North Carolina (see

Table A1 and

Table A2). In the twenty years between 2000 and 2020, North Carolina witnessed a 29% growth in its overall population as compared to a 17% population growth nationwide. Charlotte, on the other hand, experienced a 60% increase in its overall population. In those two decades, Charlotte’s racial and ethnic composition changed as well. The “Browning” (

Jones 2019) of the city was evident to all as it became more racially and ethnically diverse. In 2000, about 58% of the city’s population was White, but over the years, there was a decline of 31% in the White population, in trend with the 21% decline across the nation. Conversely, in the 2000 to 2021 period, Charlotte’s Latino and Asian populations saw a dramatic increase by about 101% and 74.8%, respectively. Blacks experienced a slight increase in their population from 33% in 2000 to 35% in 2021. These demographic shifts embodied the changing demography, growth, and maturity of a New South financial center.

In response to the uneven distribution of economic and social growth across Charlotte, by 2017, Charlotte residents were demanding change on multiple fronts. Vi Lyles was a beneficiary of that enthusiasm for change as a 2017 mayoral candidate, a “historic first” campaign and victory (

Benjamin 2023) that we contend set the groundwork for constituent expectations about her governance and leadership style. Rather than duplicate the invaluable findings from

Benjamin (

2023) and

Austin (

2023) about the Lyles 2017 victory and its meaning, we stress three things here about the 2017 electoral context as background information. First, by 2017, Lyles was not an amateur politician. She was a former assistant city manager, won election to the City Council in 2013, and had been elected mayor pro-temp in 2015. Second, Lyles had successfully defeated incumbent Mayor Jennifer Roberts in the Democratic Party primary in September 2016, a rough-and-tumble primary battle, by nearly 10 percentage points. Third, in the 2017 mayoral campaign, Lyles went on to defeat Republican City Councilmember Kenny Smith by 18 percentage points. The hardnosed 2017 campaign also featured racialized overtures, which the mayor adeptly handled (

Benjamin 2023).

Take, for example, a December 2018 article by the Editorial Board of

The Charlotte Observer, titled “One year in, Vi Lyles has been the mayor Charlotte needed”, which hailed the mayor’s leadership when discussing the positive comments by Republican state legislators about Mayor Lyles. The board wrote, “You probably wouldn’t have heard two conservative lawmakers say such things about a Democratic Charlotte mayor a couple years ago. But [Republican State Senator] Bishop says it’s no concession at all. ‘I have a very high opinion of Vi Lyles’, he told the editorial board this week. ‘Her style is so even-handed and thoughtful and positive’”. It was perhaps news items like this 2018 editorial that helped propel Mayor Lyles to a 2019 re-election victory. Nonetheless, the campaign was hard-fought, and incumbent Mayor Lyles easily defeated Republican David Rice. An article from

The Raleigh News & Observer outlined the importance of Lyles’s re-election victory, noting: “Mayor Vi Lyles wins a second term; council incumbents re-elected” and declared that Vi Lyles had become the first mayor since 2011 to land a second term in office. Mayor Lyles won 77% of the vote and beat Rice by 55 percentage points. A

Charlotte Observer article also noted the campaign context: “In her campaign, Lyles pledged to focus on public safety as Charlotte’s homicide total has risen above 90. She’s also emphasized her transportation initiatives, which include ‘rebuilding’ the city’s bus system and securing funding to expand light rail” (

Kuznitz 2019).

In 2019, the editorial board for The Charlotte Observer praised and endorsed Mayor Lyles in an article headlined, “Charlotte mayoral endorsement: What you might not know about Vi Lyles”. Newspaper editors highlighted their interpretation of how Mayor Lyles’s leadership had benefited the city of Charlotte. They wrote the following:

In her first term, Vi Lyles has helped Charlotte repair relationships with previously hostile lawmakers in Raleigh. She’s helped the City Council navigate through the potential choppiness of new, bold voices mixing with veteran members. She’s strengthened the city’s relationship with its corporate community. She has earned a second term as mayor.

We interpret this 2019 editorial as The Charlotte Observer’s attempt to frame Mayor Lyles as a unifying force for the city’s diverse ethno-racial community.

We assert that the 2017 and 2019 elections of Mayor Lyles reflected both the political demography of the post-9/11 New South as well as the altered calculus defining how Black officialdom would address demands over Confederate memorials. As homages to enslavement, Southern segregation, and segregationist philosophy, the taxpayer-supported Confederate memorials in Charlotte reminded observers of the racialized subjugation of public spaces and the multigenerational conspiracy by elected and appointed officials to sanction and perpetuate notions of White supremacy and Black inferiority. Conflicts over those memorials also channeled debates over the best ways to ameliorate vestiges of racialized enslavement, over the utility of race-conscious campaign and governance styles, and over the spoils of gentrification. Thus, for many, the presence of taxpayer-supported Confederate memorials served as literal markers and figurative markers denoting two things: first, the limited reach of Black voters to change the physical, narrative, and aesthetic dimensions of public space; and second, the omnipresent conundrum facing Black mayors, especially “historic firsts”, who desired to change the limited reach of Black descriptive representation. Here the ironic nature of Black criticism against Black mayors of cosmopolitan urban centers for not vigorously addressing the Confederate Memorial Controversy deserves some explanation. Bluntly put, the BLM-inspired calls for Black officials to remove taxpayer-supported Confederate memorials thus embodied a particularized insistence that the beneficiaries of Black electoral power topple (pun intended!) symbols of anti-Black subjugation if they were beholden to the moniker of being descriptive representatives.

3. Data and Methods

Following the guidance of

Creswell and Plano Clark (

2011), regarding mixed methods research designs, we utilized an embedded design—a concurrent “mixing at the level of design” of “quantitative and qualitative strands” (

Creswell and Plano Clark 2011)—to study public reaction to the Charlotte Legacy Commission and to the actions of Mayor Lyles. Our mixed methods “embedded design” case study approach combines an analysis of survey data with a content analysis of government documents and of local newspapers. The reasons we employ this mixed methods approach are for “completeness” and “context” (

Bryman 2006), i.e., to ascertain a “more comprehensive” “contextual understanding” of the factors shaping how a city’s first Black woman mayor contended with constituent demands regarding its public-facing Confederate memorials.

3.1. Methodology

We conducted a content analysis of background documents related to the Legacy Commission; a content analysis of 2019–2020 newspaper articles from two local papers, The Charlotte Observer and The Raleigh News & Observer; and a secondary analysis of statewide survey data from the 2020 SurveyUSA News Poll. Our content analysis enabled us to explore whether and how media accounts emphasized race, gender, and social change to frame the work of the Legacy Commission. We supplemented the content analysis of newspapers with the survey data to estimate a multinomial logistic regression model outlining the factors shaping North Carolina residents’ views on the removal of Confederate memorials.

3.2. Document Analysis: Legacy Commission Materials

Employing a “reflexive thematic analysis” approach (

Braun and Clarke 2019;

Morgan 2022) common in qualitative research, we examined and analyzed each of the seven public hearings conducted by the 15-member Legacy Commission from August to December 2020, where participants discussed the origins and way forward with Confederate memorials in Charlotte. The city of Charlotte also streamed the public hearings and made them available online. We also interviewed Mayor Lyles about the work of the Legacy Commission. We approached this documentary evidence as a vehicle from which to view the sociopolitical context of Charlotte during that time, how the media covered Mayor Lyles’s leadership style, and how residents may have viewed the controversy.

3.3. Newspaper: Article Sampling

We employed a “critical discourse analysis” framework (

Fowler et al. 2021;

Nielsen 2013;

Richardson 2017) to examine how the news media framed the governance style of Mayor Vi Lyles amid the Confederate Monuments Controversy. We selected

The Charlotte Observer and

The Raleigh News & Observer as the most assessable newspapers of record in the jurisdiction. We collected 1153 articles published between 2019 and 2021 under the search terms “Vi Lyles/Mayor Lyles”, “Confederate/Confederate Memorial”, “Community”, “Black Lives Matter/BLM”, and “Legacy Commission”.

We used a three-step method to determine the final corpus of articles to review out of the 1153 found. First, we used a random selector program to choose 55% of the articles from the original set. Second, we removed duplicates, removed articles with error links, and resolved the remaining discrepancies found in that second set of articles. Third, we returned to the original set to select replacements for the duplicates using the same nine criteria. Our final sample consisted of 577 usable newspaper items.

3.4. Newspaper: Coding Framework and Procedure

Using a technique typically found in analyses of television advertising (c.f.,

Fowler et al. 2021,

2016), we used a coder response form to guide our examination of each article.

6 The coder form consisted of the following ten items, which queried the following: (1) the primary focus of the article (Vi Lyles, protest against Confederate memorials, Legacy Commission, support for Confederate memorials, social change/demographic shifts, sports/recreation, elections, health, COVID-19, public safety (including police brutality or police actions or protest), or other); (2) if the article was for or against the Legacy Commission (for, neither, against, or unsure), (3) if the article emphasized race, gender, or social change/demographic shifts (yes, no, maybe), (4) the overall tone of the news item (positive, negative, or neutral), (5) if the news item mentioned the leadership or leadership style of Mayor Lyles (yes, no, neutral) and, (6) if yes, how did the media frame Mayor Lyles’s leadership style (Lyles is Conciliatory/Giving in to Demands, Lyles is Confrontational/Aggressive, Lyles is Consensus Builder/Attempting to Unify, and Other), (7) what was the target audience of the news item (racial/ethnic groups, income groups, religious groups, gender or LGBTQIA+ groups, age-identified groups, no identifiable groups, or other), (8) if the article mentioned the “New South” (yes, no, maybe), (9) how we personally felt after reading the article, and (10) if we thought that the article was well written.

3.5. Survey: Multinomial Logistic Regression Model

We applied a multinomial logistic regression model to the 2020 statewide survey data from the SurveyUSA News Poll data (N = 2853 North Carolina residents) to understand the views regarding what should happen to Confederate monuments and statues on public, government-owned property (e.g., parks, city squares, court houses) that honor the Confederacy. The poll queried North Carolina residents’ support for removing or retaining public displays of Confederate statues. The weighted regression sample for the model was 2853 residents. In this model, residents’ support for Confederacy statues (Remain, Remove, Not Sure) was considered as the outcome or dependent variable. The independent variables included gender, race and ethnicity, ideology, age, income, education, party affiliation, and urbanicity.

The following section describes the dependent and the independent variables used in the model. For our dependent variable, we used the survey question, “What should happen to statues located on North Carolina public property that honor the Confederacy?” The original variable included five categories, namely, Leave as They Are, Leave in Place/Display Historical Context Nearby, Remove from Public Display Altogether, Move to Designated Civil War Battlefields and Cemeteries, and Not Sure. We combined “Leave as They Are” and “Leave in Place/Display Historical Context Nearby” to form the “Remain” category, and “Remove from Public Display Altogether” and “Move to Designated Civil War Battlefields and Cemeteries” to form the “Remove” category, keeping the “Not Sure” category as it was. “Not Sure” was the reference category.

Our independent variables follow traditional standards. The variable on gender was categorized as female (woman) and male (man), where male was the reference category. The race and ethnicity variable included four categories, Black, Hispanic, White, and Asian/Other. We used Asian/Other as the reference category. The four categories for age groups included 18–24 years, 25–44 years, 45–64 years, and 65 years and above. The first three categories were compared with the oldest age group of 65 years and above. The variable income level included three categories, where we compared residents earning between the ranges of USD 40,000–USD 80,000 and more than USD 80,000 with residents earning less than USD 40,000. The variable indicating residents’ levels of education consisted of three categories, namely High School, Some College, and Four-Year College Degree. We took High School to be the reference category for this variable. Rural, Suburban, and Urban categories formed the urbanicity variable, with Urban as the comparison category. Party affiliation was measured as Democrat, Republican, Independent, and Not Sure. Finally, ideology consisted of six categories. We used “Not Sure” as the reference category for party affiliation and ideology.

4. Results

Below, we present findings from our mixed methods approach. We first interpret the results of the multinomial logistic regression model estimating North Carolina residents’ perceptions in 2020 about the public display of Confederate statues. We then examine findings from our content analysis of documents from the Charlotte Legacy Commission and of local newspaper items.

4.1. Multinomial Regression Results

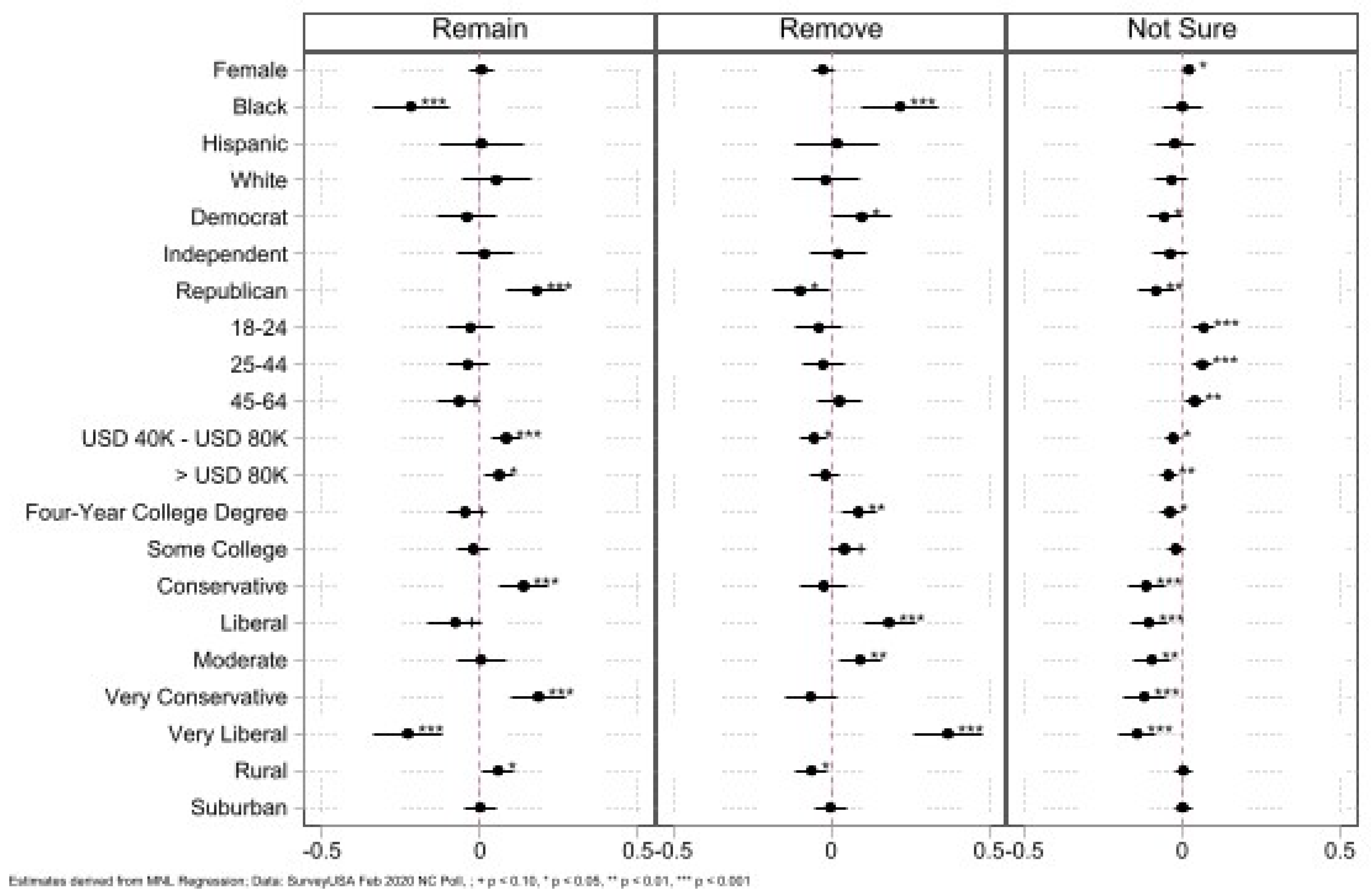

Table 1 presents the odds ratios from the multinomial logistic regression estimates for the Remain and Remove options in relation to the Not Sure option for North Carolina residents’ support for the public display of Confederate statues. Our results show that none of the categories in the race and urbanicity variables are statistically significant.

Republicans were more likely to select the Remain category relative to those who selected the Not Sure category for public display of Confederate statues. The results also indicate that the range of age values from 65 years or older to 18–24 years decreased the odds of selecting the Remain category by 68%. Switching from the income category of earning less than USD 40,000 to earning more than USD 80,000 increased the odds of selecting the Remain option by 106%. Switching from the Not Sure option of political ideology to the Very Conservative political ideology increased the odds of selecting the Remain option by 349%. The analysis also indicates that residents with a four-year college degree were more likely to select the Remove option for public display of Confederate statues as compared to selecting the Not Sure option. Residents whose political ideology aligned with being liberal, moderate, or very liberal were more likely to select the Remove option than the Not Sure option for public display of the statues. Similarly, the odds ratio associated with selecting the Remove category was high for self-identified Democrats.

The average marginal effects from the multinomial regression estimates show the importance of race, ideology, and education in shaping support for and opposition to efforts to remove Confederate memorials (see

Figure 1). For instance, residents identifying as conservative and very conservative were more likely to choose the Remain option than to choose the Remove or Not Sure option, holding the covariates at their observed values. Residents earning incomes in the range of USD 40,000 to USD 80,000 and more than USD 80,000 were less likely to select the Not Sure and Remove options. Residents from rural areas were more likely to choose the Remain option. The average marginal effects also show that Black residents were more likely to select the Remove option and less likely to select the Remain option. Residents holding a very liberal political ideology were more likely to choose the Remove option. That the opinions of North Carolina residents were split by social identity is unsurprising. Nonetheless, these opinions clearly shaped the political context informing what was happening in the city of Charlotte and the potential cleavages within residents.

4.2. The Work of the Legacy Commission

The first few public hearings of the Legacy Commission were specifically focused on informing residents about the rationale for the special committee and how the commission would evaluate the city’s Confederate memorials. For example, the first meeting was on 12 August 2020, and the main presenter was Karen Cox. She covered the “Lost Cause” as being the reasoning behind the building of Confederate memorials. She also explained how Charlotte participated in celebrating the Lost Cause, which commemorated the values of the Confederacy. The second meeting, on 9 September 2020, discussed slavery, the Civil War, and the rise of White supremacy in Charlotte. Dr. Willie J. Griffin covered slavery in Mecklenburg County and the emergence of White supremacy after the Civil War, which included a campaign against Black voting. The third meeting, on 23 September 2020, was the review of streets named after Confederate figures proposed to be changed. The Legacy Commission decided to create a list of criteria for measuring recommendations. At the next meeting, on 7 October 2020, the commission discussed criteria for recommending street name modifications. Names associated with Confederate leadership and names associated with White supremacy were given the highest priority for change.

Public input was requested for the next meeting. On 21 October 2020, the commission discussed eight recommendations for Confederate monuments in Charlotte. In the meeting, a special guest from the Charlotte city government explained the process through which street names can be changed. Later, the chair, Emily Zimmern, called for voting on recommendations for Confederate memorials and monuments. The commission passed all eight recommendations (see

Table 2). At the next meeting on 28 October 2020, the commission reviewed the final report to be submitted to the mayor and the general public, then finalized pending votes. Commissioners also certified street names to be changed. The final meeting, on 9 December 2020, was a review of the media coverage and response to the final report, a discussion of a community request to the commission, and community feedback about the commission’s work and recommendations. These late-2020 recommendations of the Legacy Commission are best examined against the backdrop of persistent racial cleavages in perception regarding public memorialization of the Confederacy as shown by the results above from the 2020 SurveyUSA Poll (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

4.3. Local Media Coverage and Tone

As shown in

Table 3, out of the 577 articles that were included in the sample, most came from the local Charlotte paper examined. With regard to tone, 3% (n = 18) of the articles were coded as having a focus on Mayor Lyles, and 4.5% (n = 26) focused on the Confederate Memorials Controversy or the Legacy Commission. Public safety accounted for 11.4% (n = 66) of articles, and 74.5% (n = 430) of the articles discussed other issues including but not limited to COVID-19, elections, health, and sports.

To examine the tone in selected newspaper stories, we coded items as having a positive, neutral, or negative tone. As shown in

Table 4, 58.4% of the articles were coded as having a neutral tone (n = 337); the shares of articles coded with a positive tone and negative were equal at 20.8% (n = 120 for each). Additionally, we examined how the tone was used in articles discussing Mayor Lyles and the Confederate Memorials Controversy or the Legacy Commission. When discussing Mayor Lyles, a higher proportion of articles were coded as having a neutral tone (61.1%, n = 11) compared to having either positive (27.8%, n = 5) or negative tones (11.1%, n = 2). Similarly, when discussing the Confederate Memorials Controversy or the Legacy Commission, a higher proportion of articles contained a neutral tone (73.1%, n = 19), compared to either a positive tone (15.4%, n = 4) or a negative tone (11.5%, n = 3).

Below, we present excerpts from analyzed news items to underscore the news media’s framing of Mayor Lyles’s governance style. The first excerpt, taken from a 2020 news item in The Charlotte Observer, suggested that Charlotte needed what Mayor Lyles offered. The item reads,

Lyles has been a strong mayor in a weak mayor structure. Charlotte could use more of the steady leadership she can bring.

The second excerpt, taken from a 2019 news item in The Charlotte Observer, emphasized Lyles’s leadership style through a quote by Tom Ainsworth, a self-proclaimed “staunch Democrat”, who voted to re-elect Lyles as mayor. The article quoted Ainsworth as follows:

“I think she’s done a pretty good job so far,” Ainsworth, 66, said. “I usually give someone the benefit of the doubt after a first term. She deserved a second chance.”

Though these excepts are relatively laudatory, the overall tones of these articles were categorized as neutral. In contrast, in an excerpt from an analyzed 2019 news item from The Charlotte Observer, Mayor Lyles’s leadership style regarding coalition building was categorized as positively framed because it overtly praised Mayor Lyles:

The city’s successful RNC bid, while provoking some backlash from the left, has also brought Lyles recognition from national Republican officials that isn’t common for a Democratic mayor of a predominantly Democratic city.

Of course, the Charlotte news media did not always praise Mayor Lyles. For example, cartoonist Kevin Siers created a satirical image, titled “How Mayor Lyles reassures our immigrant community”, which poked fun at the mayor and was categorized as negatively framed. The cartoon stated, “We are inclusive… But there are still a few bugs in the system…”. It depicted Lyles holding a sign displaying ICE hugging immigrants with the caption “Safe Place Charlotte” (

Siers 2019).

4.4. Emphasis of News Stories

To assess the emphasis of the news stories on race, gender, or social change/demographic shifts, articles were coded on a scale of yes, maybe, or no in each of these categories. In all, 24% of articles were coded as having emphasized race (n = 138), as compared to no emphasis on race (71%, n = 411) (see

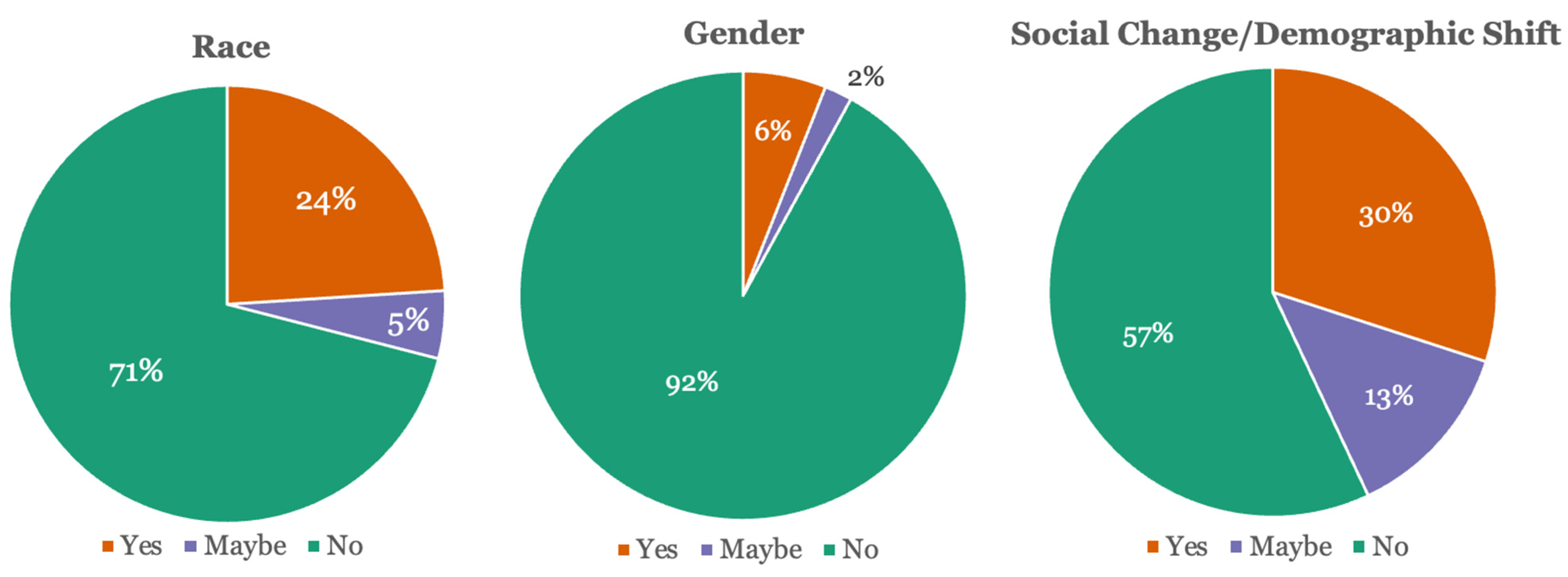

Figure 2). A small proportion of articles were coded as having maybe emphasized race (5%, n = 28). The majority of the articles were coded as having no emphasis on gender (92%, n = 533), as compared to yes (6%, n = 34) or maybe (2%, n = 10). A similar trend to emphasis on race was noticed for social change/demographic shift. A high proportion of articles were coded as having no emphasis on social change/demographic shift (57%, n = 326), as compared to yes (30%, n = 175) or maybe (13%, n = 76).

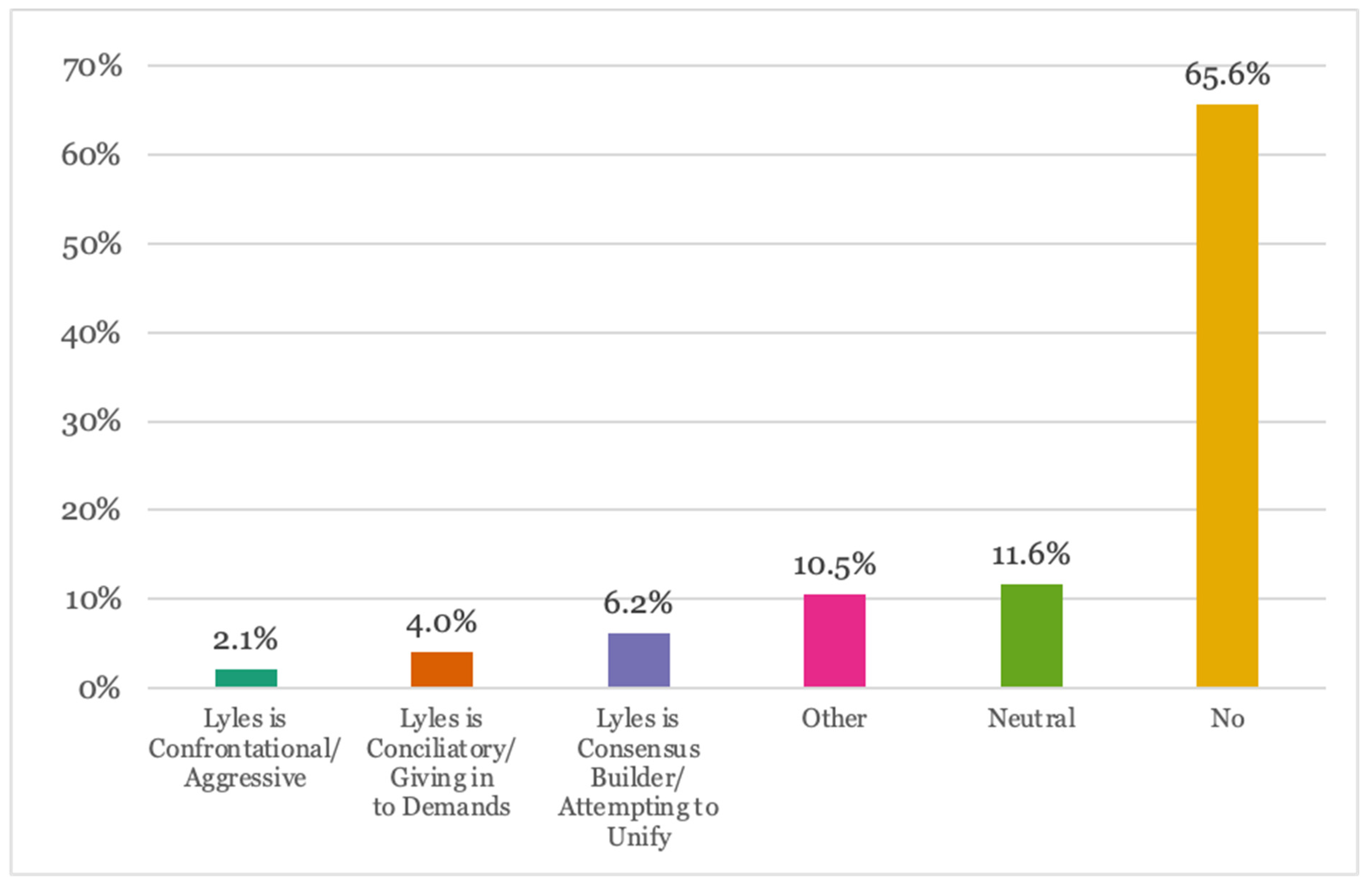

4.5. News Framing of Mayoral Leadership

Figure 3 depicts the results from our analysis of how the media framed Mayor Lyles. In the articles examined, 65.6% (n = 373) did not discuss the leadership or governance style of Mayor Lyles, 11.6% (n = 66) portrayed her leadership style as neutral, and 23.9% (n = 138) discussed her leadership style. For the 138 articles that discussed the mayor’s leadership style, we coded these as Lyles is Conciliatory/Giving in to Demands, Lyles is Confrontational/Aggressive, Lyles is Consensus Builder/Attempting to Unify, and Other. Of these articles, we found that Mayor Lyles was framed as a Consensus Builder in 6.1% (n = 35), as Conciliatory in 4.0%, and as Confrontational in 2.1% (n = 12) of the articles. A segment from an August 2020

Charlotte Observer article, entitled “Charlotte’s Mayor Apologized for the City’s Role in Systemic Racism. What comes next?” (

Chemtob and Lindstrom 2020) provides an illustrative example of how the media brought attention to both Lyles and a particular audience:

Lyles took a rare but not unprecedented step in acknowledging a city’s active role in creating inequality. Charlottesville, Virginia leaders in 2013 apologized for razing a historically Black neighborhood through the same urban renewal program, according to local media. Some cities have gone further to attempt to right historical wrongs with financial investment. Last month, Asheville’s City Council passed a resolution for reparations, though the measure does not directly provide payments to individuals. Instead, the city will fund programs to increase racial equity, such as homeownership and business opportunities for Black residents.

The authors go on to write, “In Charlotte, plans to redevelop 17 acres that were once part of Brooklyn spurred conversations about how to remedy the damage done by urban renewal, in a concept known as restorative justice”.

4.6. New Stories’ Focus and Audience Addressed

Table 5 presents results for who the audience was for the news stories and what the primary focus of the articles was. The articles were coded as addressing racial/ethnic groups, income groups, religious groups, gender or LGBTQIA+ groups, age-identified groups, or no identifiable or other groups. In all, 410 of the newspaper articles (71%) were categorized as addressing no identifiable or other groups, while 16% of articles were categorized as addressing racial or ethnic groups. Articles categorized in the individual remaining categories made up less than 7% of the total.

As mentioned above, 3% (n = 18) of articles focused on Mayor Lyles. We categorized 16.7% of those articles as addressing racial/ethnic groups and 83.3% (n = 15) of those articles as addressing no identifiable/other groups. Of the 26 (or 4.5%) articles categorized as focusing on Confederate memorials or the Legacy Commission, we categorized a high proportion of them as addressing racial or ethnic groups (84.6% or n = 22). The audience for articles categorized as having a focus on social change or demographic shifts included racial or ethnic groups (48.6% or n = 18), gender or LGBTQIA+ groups (27.0% or n = 10), no identifiable groups (13.6% or n = 5), income groups (8.1% or n = 3), and age-identified groups (2.7% or n = 1).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In the wake of a post-2016 rise in White supremacist organizing and a global resurgence in right-wing authoritarianism, the issue of how Black mayors handled the Confederate Memorial Controversy in light of the 2020 BLM anti-police brutality protests will remain an interesting subject to study. Scholars cannot easily ignore the impact of dueling constituent expectations on the future of Black electoral success (

King-Meadows 2021). In this regard, criticism of twenty-first-century “historic first” Black women mayors is illustrative of the import of counter-publics and counter-narratives.

7 Take, as examples, angst surrounding the 2008 austerity measures of Atlanta’s Shirley Clarke Franklin; the ferocity and speed of anti-COVID-19 mitigation measures installed by Washington, D.C.’s Mayor Muriel Bowser; the deracialized campaign and governance strategy of San Francisco’s Mayor London Breed (

Jones et al. 2022); and the 2019–2020 strategies to reduce violent crime of Chicago’s Mayor Lori Lightfoot. Consequently, Black frustration with Black women mayors can further contextualize the contemporary operation of Black expectations about descriptive representation (

Gillespie 2012;

King-Meadows 2021;

Wilson and Brown-Dean 2012): Black counter-publics might undermine Black women mayoralties in their quest to end the racial privatization of public space represented by Confederate memorials. Newspapers and media personalities channeling the angst of Black counter-publics, for instance, might frame a Black woman’s mayoral leadership on the Confederate Memorial Controversy as ineffectual and/or slow-moving. That news sources can perpetuate anti-woman bias and negative stereotypes of women leaders is unsurprising. Nor would it be surprising if there were racial differences in how residents living under “historic first” Black women mayors hoped their chief executive would approach the Confederate Memorial Controversy, with Black residents and liberals hoping for a vigorous engagement that privileged removal and with non-Black residents and conservatives hoping for a soft-pedal engagement that privileged stasis. Nor would it be surprising if a mayor chose stasis if they governed in a state that statutorily prohibited the alteration of state-owned memorials without approval from the state majority party. The case of the 2020 Charlotte Legacy Commission offers interesting insights into how one leader addressed those various pressures.

This article has sought to address a gap in the literature about the “new” governance styles of twenty-first-century Black women mayors by examining Charlotte, North Carolina, Mayor Vi Lyles’s handling of the BLM-inspired calls seeking the removal of public memorials to soldiers for and sympathizers of the U.S. Confederacy. We took seriously the dynamics of twenty-first-century Black electoral leadership with the backdrop of sociodemographic changes in the post-9/11 American South as well as the need for Black officialdom to navigate competing expectations about representational accountability in the context of economic shocks to and political attacks on the financial solvency of urban centers (

Benjamin 2017). Our paper asked simply the following: What did Charlotte Mayor Lyles do to address the issue of taxpayer-supported Confederate memorials in the Southern city, and how did newspapers frame the mayor’s governance style on the issue?

Our analysis of background documents regarding the Legacy Commission, of a statewide survey of North Carolina residents, and of newspaper items in The Charlotte Observer and The Raleigh News & Observer revealed much about the dynamics of the local information environment and of the demographic cleavages shaping opinions about the Confederate Memorial Controversy, the commission, and Mayor Lyles. We found that respondents identifying as highly affluent, conservative, or Republican were more likely to oppose removal, whereas respondents identifying as Black, highly educated, or liberal were more likely to support removal. We found that government documents about the Legacy Commission presented the Confederate Memorial Controversy as an opportunity for systematic introspection about the city’s history and the city’s future. We also found that the two print media outlets framed Mayor Lyles using positive tones, but that most articles were neutral. Nonetheless, we found that articles emphasized demographic shifts affecting Charlotte or that articles emphasized the race and gender of Mayor Lyles. Some articles also seemed intentionally written to pique the attention of certain social identity groups. That the articles did not often agree with Mayor Lyles was anticipated. Nonetheless, news items emphasized Mayor Lyles as a positive force for Charlotte and as a proponent of reducing the racial barriers and injustices experienced by city residents, even as news items emphasized race, gender, and/or social change when discussing Mayor Lyles or the Legacy Commission. The articles illuminated how and why North Carolinians were divided on the issue, with conservatives, Whites, and Republicans largely supporting the retention of Confederate memorials, whereas liberals, Blacks, and Democrats were diametrically opposed to said option. Comparatively speaking, the dynamics of this issue were relatively different for Charlotte than for other urban cities. Nonetheless, the stakes were high. Some residents saw the city’s handling of the controversy as important to continuing Charlottes’ reputation as a Black-led, pro-business, cosmopolitan gateway to the proverbial New South. In that way, the Legacy Commission provided a litmus test of Charlotte’s and Mayor Lyles’s well-honed images.

In other words, we contend that our findings about article tones and article contents reflected dueling narratives about the Confederate Memorial Controversy, about the leadership of Mayor Lyles, and about the Legacy Commission. Our results underscore the multilayered nature of elite and constituent responses to calls seeking the removal of Confederate memorials. Furthermore, the results confirm the complicated relationships between government responses to electoral demands, national issue environments, and locale-specific racial and sociopolitical contexts. In that regard, our results contribute to the scholarship examining how Black politicians of the early twenty-first century navigate the winds of sociodemographic and attitudinal change alongside contentious issues and differing constituent preferences.

Specifically, we assert that results from our case study on Mayor Lyles and the Legacy Commission speak to the study of the twenty-first-century “historic firsts” of Black women mayors, and of counter-publics and counter-narratives. Not only did Mayor Lyles effectively navigate Black frustration with the “politics” of the Old South and of the New South, but she also effectively muted some criticisms about Black expectations about the benefits of descriptive representations. In the end, Mayor Lyles capitalized on the controversy by presenting the Legacy Commission and its recommendations as a ground-up, citizen-based, historically informed, race-conscious remedy that would not too negatively impact business interests. The symbolic victory notwithstanding, it remains an open question as to whether the renaming of streets and locations effectively provides the substantive benefits theorized (i.e., a reduction in racially privatized public space) or moves public sentiment away from the totemism associated with Confederate material culture.

8 Furthermore, we strongly support calls for

better research on Black women mayors—represented by calls from scholars of race, ethnicity, and politics to produce more intersectionality-informed research on Black political leadership embodied in paradigmatic fashion by “political black girl magic” (

Austin 2023), Black Lives Matter, and “historic firsts” (

Simien 2015;

Simien 2022). In other words, we explicitly echo calls by Sharon Wright

Austin (

2023) and others for more scholarly attention to “political black girl magic”—defined by

Austin (

2023) as the actions of “African American political women who have used their intellect, charisma, and talent to attain their cities’ highest office” against the backdrop of historic “bigotry, harassment, marginalization, discrimination, and humiliation”. We, therefore, reiterate our colleagues’ charge that new research on Black politicians must provide greater attention to how Black women mayors “acquire” and “exercise power” while attending to the new demographic landscape of the twenty-first century. However, our findings about Charlotte suggest that the extant literature on Black women mayors might miscalculate the relationship between America’s new demography and the political destiny of marginalized groups. We further posit that the “black girl magic” paradigm view of examining Black women leaders (c.f.

Smooth and Richardson 2019;

Gillespie and Brown 2019;

Austin 2023) marked a significant opportunity to interrogate how the Confederate Memorial Controversy illuminates Black expectations for a particular type of political symbolic and substantive magic.

Overall, our findings suggest two potential negative tradeoffs of “historic first” Black mayoral leadership with the backdrop of a rise in right-wing authoritarianism in America and of a decline in public attachment to democratic norms. First, media exaltation of a tempered approach to shepherding a race-conscious public policy—one which neither overtly agitates nor placates structural racism—may fail to destabilize expectations about racial clientelism. Although conservative Whites expected stasis, they achieved only a partial victory. Although liberal Blacks expected overt denouncement and upheaval, they, too, only achieved a partial victory. The racialized expectations of responsible party government nonetheless remained intact. Second, the media’s even-handedness on the Confederate Memorial Controversy in Charlotte may have only strengthened the resolve of White supremacists to see their proffered inheritance as unassailable and to see their heir claims as legitimate. By not aggressively denouncing all the ways in which any public homage to White anti-Black racial caste authoritarianism in Charlotte damages its present and future residents, the mayor, the local media, and the Legacy Commission may have sidestepped an opportunity to diminish the “totemism” of Confederate material culture among those Whites interested in the upward economic trajectory of the New South. The socializing benefit of “historic firsts”, as a racism mitigation and racism reduction mechanism, we suggest, depends on how effectively those elected officials showcase the economic and social costs levied on future generations by the present perpetuation of racial animus, political exclusion, and racial caste authoritarianism.