Abstract

Child-led research is gaining increasing attention. Such research involves children leading throughout the research process, from research design to dissemination. Child-led research has tested adult-centric research assumptions, with debates in the literature about researchers’ expertise and responsibilities. If these debates are testing for child-led research undertaken with older children and young people, they are even more so for young children below school-starting age. This article examines child-led research undertaken in a Froebelian early years setting, over 11 months, with 36 children aged between 2 and 5 years, from the adult facilitators’ perspectives. The article utilises the research’s documentation, including mind maps, photographs and story books, songs and video recordings, and an interview undertaken with the facilitating early years practitioner and supporting academic. Learning from this, the article challenges the assumption, in much of the literature on child-led research, that adults need to transmit their knowledge of research methods to children. Instead, a ‘slow pedagogy’ can build on children’s own knowledge, collectively, with time to come to research understandings. The article concludes that child-led research is feasible with young children, but the research process can include or exclude certain forms of children’s communication, making some children more ‘competent’ to undertake research than others.

1. Introduction

Child-led research is growing in popularity. Childhood studies, and related fields, have foregrounded children’s involvement in research. For several decades, advocates have argued for research with, and not on, children, and recognition of children as important research participants (e.g., James and Prout 1990; Bradbury-Jones and Taylor 2015). Ethics, methods and projects developed, seeking to ensure the meaningful research participation of children. Interest expanded alongside, to involve children not only as research participants but also in additional—and influential—roles within research. These have ranged from children as expert advisers to research projects (Collins et al. 2020), to children as peer researchers during fieldwork (Coppock 2011), to children developing outputs for policy and practice influence (Houghton 2015). Co-production and co-design are increasingly used, where children and adult researchers work together on a research project from inception to completion (Liabo and Roberts 2019). A further option is child-led research: this is where children take the lead throughout the research process, from determining the research questions, to carrying out the fieldwork, to analysis and dissemination (Graham et al. 2017).

As we wrote (referring to a previous research article), child-led research may be growing in popularity, but it also has proved particularly testing for ‘traditional’ academic research. Questions have been raised about whether it can meet research standards, when children do not have the training, skills, experience or power to do so (Hammersley 2017). Spyrou’s rejoinder (Spyrou 2018) queries the boundaries of research, suggesting that an expanded definition of research that encompasses “participation, political engagement and social change” (p. 166) can provide a place for child-led research. Thomas undertakes a masterly overview of these debates, to suggest a contextual approach: “The questions have to be about which children are competent to conduct what kinds of research, in what circumstances and conditions; and which children might want to conduct research and whether it would be to their benefit, also in context” (Thomas 2021, p. 198). Thus, according to Thomas, children’s competency is a relevant consideration for child-led research, which must be contextually considered in light of the circumstances, the kind of research and children’s own motivations.

If such questions are raised about child-led research generally, an even sharper critique is likely for research undertaken by young children. Having supported child- and youth-led research, we had the chance to research and reflect on the claims for and against child-led research, as adult, child and youth researchers in our 2019 article (Cuevas-Parra and Tisdall 2019). With the opportunity presented by Froebelian Futures1, a 3-year funded project designed to increase understanding of a Froebelian approach to early education, we sought to explore child-led research with young children, under the age of five, in a nursery that would be highly supportive of the idea that children could generate knowledge through research. This article reports on the learning and challenges of the first phase of child-led research (August 2021–July 2022).

Below, the article outlines in more detail the definition, claims and critiques of child-led research. It then presents the methodology for the child-led research itself, and the ensuing reflective research and analysis. Three themes are subsequently discussed, based on the research documentation and reflections, which particularly speak to the debates in the literature: what is research; the roles of adults within child-led research; and how the process can include or exclude certain forms of children’s communications. The article ends by questioning some of the findings and subsequent conclusions, frequently found in reports of child-led research, such as children finding it difficult to identify a research topic, the necessary tie between child-led research and impact, and the assumption that the adults’ role is to transmit research skills to children. Through learning with young children and a Froebelian pedagogy, the article identifies alternative ways for adults to frame and support child-led research, which can be useful for all ages of children and young people. Further, it challenges the continued reliance on words (whether written or verbal) which dominates childhood research, to find ways for research that would be more inclusive of all children’s preferred forms of communication.

We note that this article is informed by children’s reflections, but represents adults’ learning and perspectives. Children have presented their own research to their nursery community, a session at a play festival and, with some caveats (see below), at a conference for adult practitioners and academics.

Definitions, Claims and Critiques of Child-Led Research

Child-led research does not have a single, agreed definition. Kellett provides one that is oft-cited: “Research that children design, carry out and disseminate themselves with adult support rather than adult management” (Kellett 2010, p. 195). This is further expanded by child researchers2 and their facilitators, in the definition published by World Vision International:

This definition underlines two elements which are very important to the child researchers involved with World Vision. First, as with Kellett (2010), adults have a supportive role but not a determinative one. Children are in control of the key research decisions. Second, the child researchers are motivated to be involved because of their own experiences and wanting to make an impact. Both elements are identified as key to children’s motivation to participate in child-led research and for the research’s success (Cuevas-Parra and Tisdall 2019).Children and young people lead their own research process (designing the questionnaires, collecting information, analysing the results, and writing and disseminating their report). In this process, children and young people can be assisted by an adult facilitator, but this adult only helps the young researchers and doesn’t manage or direct the research project. Child-led research is always connected to children’s and young people’s interests and their motivation to make a difference.(World Vision International 2015, p. 9)

Different terminology can be used in the literature to describe very similar activities to child-led research, such as participatory action research (McMellon and Mitchell 2018) or child-driven research (Mutch 2017). Despite the number of potential terms, they have common characteristics. Children’s involvement is typically time-limited, for the research project, involving a core group of children. The children determine the research direction and design, and they undertake an in-depth inquiry. The children work collectively, having time and space to undertake their research. A key adult or two, supported by their own organisation (e.g., a school, youth group or non-governmental organisation (NGO)), helps, in turn, to support with practicalities and facilitating the process. Further, the adults and organisations frequently connect children to adult decision-makers, with the intention that the child-led research will influence the decision-makers and impact on decisions. To support such activities, there is an ever-growing array of guidelines and toolkits, from Kellett and colleagues’ own curriculum for children (Kellett 2005) and World Vision International’s advice (World Vision International 2017), to very recent recommendations co-designed with children and young people (e.g., https://triumph.sphsu.gla.ac.uk/resources/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

While child-led research may be increasingly popular, it risks being seen as merely an innovation, something faddish to capture decision-makers’ attention (see Cuevas-Parra and Tisdall 2018), and excluded by some from ‘serious’ research. For example, Hammersley writes that children cannot undertake social research. Children, he argues, are very unlikely to have the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out such specialised activity:

Further, he notes, researchers have responsibilities in terms of ethics and validity of the findings. Researchers, therefore, must have sufficient control of research decisions, so they can deliver on such responsibilities. Implicitly, Hammersley suggests that children are not likely to have such control, and thus it is not fair nor possible for them to take on such responsibilities (see also McCarry 2012). Kim (2016, 2017) develops related arguments, questioning children’s competency to undertake research, whether they are necessarily better researchers with their peers and—more broadly—whether the research is really as child-led, participatory and empowering as claimed.In methodological terms, I think it is important to recognise that social research is a specialised activity that demands knowledge and skills that a very small proportion of adults—and hardly any children—have, and ones that cannot be acquired quickly.(Hammersley 2017, p. 122)

These debates are partially dependent on how social research is defined and justified, as Hammersley himself recognizes (Hammersley 2017), see also (Hammersley and Kim 2021). There is no settled definition of social research, as reviewed by Khan and Reza (2022), but most definitions start with the identification of a social problem and subsequent investigation. Neuman and Robson, for example, give a fulsome definition:

This definition emphasises the outputs of the investigation: new knowledge, or, at least, documented or refined learning. While the researcher or research team will no doubt learn themselves as they undertake the research, the learning is not just for themselves; social research is about identifying a gap in knowledge and seeking to fill it (Müller-Bloch and Kranz 2015)—and, presumably, to share with others. In potential contrast, the emphasis of education for children is on the children learning: “Education is the process of facilitating learning or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, beliefs and habits” (UNESCO 2023). The child is then acquiring knowledge, rather than producing it; the learning is being internalised by and for the child, rather than them necessarily sharing their learning with others. Learning is thus essential to both social research and to education, but they differ in who is supposed to be learning. Child-led research is reversing the typical adult–child relationship, where adults transmit knowledge and children learn it, in education, to children developing and sharing their knowledge, in child-led research.It is a process in which researchers combine a set of principles, outlooks and ideas with a collection of specific practices, techniques, and strategies to produce new knowledge. Social research is conducted to learn something new about the world, or carefully document expectations or beliefs, or refine their understandings of how the social world works.(Neuman and Robson (2018), quoted in Khan and Reza 2022, Table 3.1)

Much of child-led research to date has been with older children—young people—and sometimes into primary school age (Kellett 2010). If Hammersley and Kim were critical that children are unlikely to have the competency or skills to carry out research or to be in a position to take on ethical and analytical responsibilities, these are even more likely to be concerns for younger child researchers, who have less opportunities to have learnt these skills or to have such control. Thus, attempting child-led research within an early years setting, with younger children, is particularly testing to child-led research’s claims and critiques. This is what we undertook with the child-led research, as part of the Froebelian Futures project: its methodology is discussed below. This article thus contributes to the childhood research literature in exploring the claims, experiences and challenges of child-led research with young children and, in turn, asks questions of the broader social sciences research field in terms of assumptions about who holds knowledge and how it can and should be communicated.

2. Materials and Methods

The child-led research reported in this article sits within the broader Froebelian Futures project. The project has a number of workstreams, including practitioner inquiry and a practitioner network, the curation of related resources, and knowledge exchange and training. It is a partnership project with the City of Edinburgh Council, one of its nurseries Cowgate Under 5s Centre, and the University of Edinburgh. We report here on the first year of trying out child-led research (which is called the ‘first phase’), as we plan for another cycle of child-led research in the second year of Froebelian Futures. Below, we outline our ‘research on research’, both what we sought to learn as adults from trying out child-led research with young children, and the process of the child-led research itself.

2.1. Research Aim and Questions

From the adults’ perspectives in Froebelian Futures, we aimed to trial child-led research in a Froebelian early years setting, with three associated research questions:

- (1)

- How was ‘child-led’ understood, enacted and experienced with young children, in child-led research, from the perspectives of the children themselves and the adult researchers involved?

- (2)

- How did the child-led research share or challenge Froebelian principles?

- (3)

- What can be learned for future child-led research projects, for children under school age?

This article shares three themes that arise from answering these research questions.

2.2. Recruiting Child-Led Researchers and Adult Participants

Informed consent was sought from all parents/carers at Cowgate under 5s Centre for their children to participate in the child-led research. Children then opted in themselves, with due care taken to inform them, in an ongoing way, about the project and participation in the child-led research. Thirty-six children, aged from two to five, decided to participate over the time of the child-led research, with a core group of six children largely consistent throughout. Three nursery staff members, who were also members of Froebelian Futures, were involved, and Emma particularly facilitated and supported the child-led research. Kay, a University of Edinburgh adult researcher, was also involved, but by distance, as the research was undertaken during COVID-19 restrictions.

2.3. Methods Used in the Child-Led Research (by Adults and by Children)

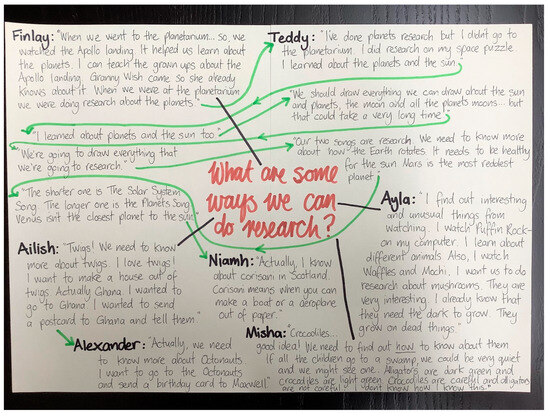

A range of methods were used in the nursery to generate and document data: discussions leading to mind maps, mind lists, drawings, photographs, video and audio recordings, lived stories, and displays. Mind mapping was a very familiar method to the children, used generally by Emmaand others in the nursery, to record on a sheet of paper the range of children’s ideas on a particular topic (see Figure 1). Mind lists were initiated by one of the child researchers, who described them as “a list you make to make your mind grow stronger and to remember things”, and tended to be undertaken with an individual child researcher andEmma. Lived stories were another method frequently used in the nursery, and these were narrative observations. They sought to capture both learning moments and/or other pertinent moments for the child, appreciating children’s rich and complex lives (McNair et al. 2021). These stories were written by a practitioner, checking in with the child, seeking to stay very close to what the child did and said, and how they otherwise communicated. A book was created by Emma and the children, predominantly containing photographs, sharing key moments and reflections on the research journey.

Figure 1.

Mind map of ‘What are some ways we can do research?’.

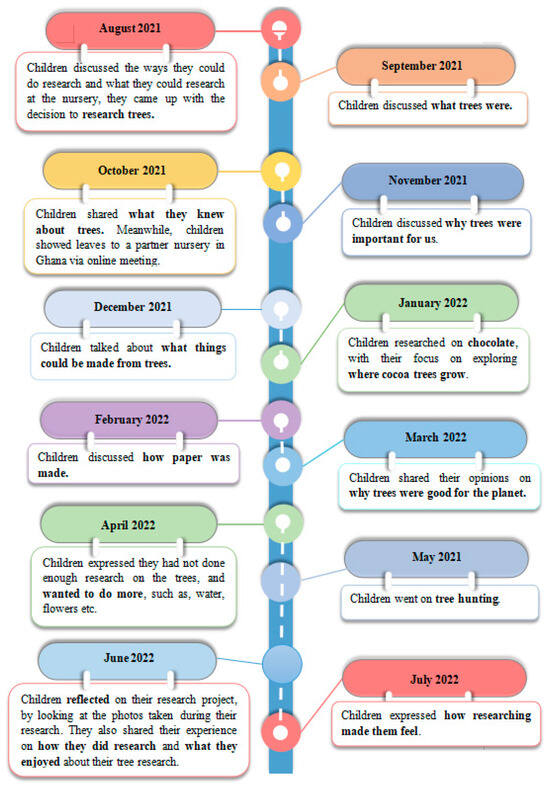

This phase of child-led research was undertaken over 11 months, with key stages summarised in Figure 2. The first stage sought to explore what children understood as research, how it could be undertaken, and then what topic they wanted to explore. After consolidating the topic of trees, they undertook iterative stages of investigation, ranging from meeting online with their sister nursery in Ghana to explore what trees grew in each context, to why trees were good for the planet, to what could be made from trees. The children initiated a tree hunting trip at the end of May, with interested children gathering at the nursery, some of them equipped with clipboards, papers and pencils, and then investigating the streets around the nursery for trees and speaking to community members about trees. Throughout, the children interviewed other adults, from the nursery staff and outwith. In June and July, Emma and the child researchers developed their research book and increasingly shared their activities, their current ‘provocations’ and learning in a nursery display, to involve others at the nursery, and reflected on their research experiences.

Figure 2.

Timeline of summarised activities of child-led research, first phase. Source: The timeline was designed by Sumei Gan.

2.4. Data Management and Data Analysis

All documented data were initially photographed or otherwise recorded by Emma staff, using their nursery IT devices. These records were then uploaded to the secure server at the University of Edinburgh. A postgraduate student, Sumei Gan, subsequently undertook secondary data analysis of the child-led research and interviewed both Emma and Kay on their experiences of this first phase of the child-led research. The interview was audio-recorded, transcribed, and similarly uploaded to the secure SharePoint. The minutes of research team meetings were also sources of data, kept on the secure server. In terms of reflecting on the research process, the focus of this article, reflexive thematic analysis, was undertaken following Braun and Clarke (2021), with the identification of codes and then themes. Attention was given to the different forms of data, recognising that the method will have influenced the data collected, and to patterns and outliers, to refine the findings.

2.5. Ethics

Ethical approval was gained first from University of Edinburgh and then the City of Edinburgh Council. A wide range of ethical issues were outlined, from informed consent to agreement to name the nursery, to inclusivity of potential participants, to anonymity. Two issues were particularly salient. First, once we had provided information verbally and in writing to all parents/carers, and received written consent forms saying we could ask their children to participate, we sought to ensure initial and ongoing consent for the nursery children to participate. The nursery’s approach generally welcomes children to initiate and opt in/out of activities, and children did express such agency during the child-led research. Nonetheless, this project faced similar dilemmas as others have, regarding whether children would distinguish the child-led research from other nursery activities, and whether they realised how the data might be used in the future (Kim 2017). Second, anonymity is commonly promised to research participants, and particularly children, as a protective measure. However, in this case, children were researchers, and thus it was important to recognise their ownership. We therefore proposed following the nursery’s general approach of using the first names of children but not their surnames, in reporting the research. We also had exceptions regarding anonymity, should there be concerns of a child or someone else being at risk of significant harm, where we would follow the nursery’s child protection procedures. Ethics remains an ongoing consideration for the research team, and is regularly considered at research team meetings.

2.6. Research Limitations

This child-led research was undertaken in a particular setting (see below), and undertaking such research in a range of settings, with different pedagogies, would further illuminate its possibilities and challenges. As described above, we had anticipated the University academic team to be present in person, providing an opportunity for observation of the child-led research in action. This was not possible, due to COVID-19 and the prohibition of in-person research by those external to the setting. Future research could incorporate this method. The recruitment of children was inclusive, in terms of children ‘opting in’ themselves. As we discuss below, children under 2 years of age did not become part of the ‘core’ child researchers, and we look to explore in the next phase how we could be more inclusive of children who do not (choose to) communicate by words, to stretch the boundaries of child-led research and social research more generally.

2.7. Note on Early Years Setting

The Froebelian context was an important one for this research and for the key themes we explore below for the article. Cowgate under 5s Centre is a leading Froebelian nursery, and the nursery research team members were all deeply embedded and committed to Froebelian pedagogy. Such pedagogy fits well with the participatory aims and claims of child-led research, as can be seen by Liebschner’s discussion of Froebelian pedagogy below:

Children’s independence and creativity do not mean adults are not involved, according to Froebelian pedagogy, as adults have a key role to enable children. Adults need to engage with children, “tuning into what fascinates them”, and then adults can share and explore knowledge with them (Bruce 2021, p. 120). Thus, Froebelian pedagogy has similarities to child-led research, in respecting children’s own abilities to learn and reflect, to lead activities, and for adults not to be in charge and didactic, but to have an enabling role. Certain subtle but potentially important differences between child-led research and Froebelian pedagogy are explored below.With increased intelligence the child needs to reflect on [their] experiences and therefore needs to represent [their] own thinking in terms of actions and language … it is the child’s activity which provides [them] with the point of focus which then turns to knowledge … Discrepancies between what was known and what was new would prompt the learner to ask appropriate questions … unless the child [themselves] was aware there was a problem, no learning could take place.(Liebschner 1992, pp. 132–34)

3. Results and Discussion

In considering the data in light of the debates around child-led research, three themes are particularly relevant. First, the data raise questions about what is research and what research the children wanted to be involved in. Second, this child-led research supports and extends the literature’s discussion of the role of adults. Third, the child-led research highlight how the research process can include or exclude certain forms of children’s communications, making some children more ‘competent’ to undertake research than others. These themes are further explored below.

3.1. What Is Research?

The impetus for child-led research came from the adults involved with Froebelian Futures, as they developed the original proposal. Some consultation with children at the nursery was undertaken then but, by the time the project started, many of those children had left the nursery for school. The adult team thus had to consider how to start off the possibility of child-led research, with children who might not have an awareness of what research is or could be, or might not be interested in taking part. From the start, therefore, the project raised issues of definitions and understandings of research, how it should be undertaken—and how to begin.

To start off the process, the practitioner, Emma, began gradually, communicating with interested children about their understandings of research and how it might be undertaken (see Figure 1 for one mind map). Some older children were familiar with the word research, seemingly drawing on family and media resources, such as Ayla reporting she found out “interesting and unusual things” from watching shows on computers. The children shared different ways of learning things, some familiar to social research methods, like asking people, and others that fit more generally with participatory or creative methods, like fieldtrips and games. The collective mapping and sharing of views involved these older children sharing their knowledge, ideas and experiences with other children who were less familiar with these ideas, building up a collective understanding of what research could be for them. Thus, with time dedicated and cycles of listening, reflecting and discussing, an understanding of what their research could be grew amongst the interested children—who then went on to decide on a topic.

If child-led research is externally funded, often the broad topic is already set for the child researchers and children are ‘invited in’ to the research to then refine the research questions and the subsequent methods (Franks 2011). When child-led research is more open, some adults report that it can be difficult for children to find and settle on a topic, and particularly one that is feasible to research (e.g., Michail and Kellett 2015). This was not the case for this child-led research. The children’s mind mapping indicated a range of potential topics, with some sparking reciprocal interest as the children discussed them. This coalesced, much more quickly than the earlier discussions about how to research, around the topic of trees. Somewhat surprisingly for the adult academic researcher, Kay, coming to a topic focus was not a difficult or lengthy process, and a group of children volunteered to undertake the child-led research with alacrity.

Perhaps because of the openness to children’s own understandings of research and their choice of topic, the focus on trees did not start off with a particular goal of social impact—a key component of the child-led research definition from World Vision above. Its early stages seemed more similar to an investigation in schools, where a topic is researched for information, or perhaps in the natural sciences, which has different sorts of research questions. For example, in November and December 2021, the children researched what things were made from trees, such as fruit and paper. The children did not express a particular concern that their research should have an impact, throughout the process, unlike child and youth researchers on other projects (see Oliveras et al. 2018), and something now often demanded of social science adult researchers.3 This fits with Froebelian principles, which are not fixated with outcomes, and which value and enable the child to be an “independent, searching and creative person” (Liebschner 1992, p. xiii), and with the child-led research potentially being a form of learning, rather than research seeking to have social impact.

While this lack of fixation on impact was challenging to the adult academic researcher, Kay, as the research evolved over the months, methods at times became applied, and impacts were inspired at the nursery. Their interest in researching trees led to the child researchers to ask for more trees to be in the nursery, and particularly more trees for climbing. Learning about the research, parents gifted trees to the nursery. Further, a linden tree was purchased—a symbolic reference to Froebel, as his favourite tree—and became a central feature in the building. Following the children’s expanding interest in trees, nursery staff arranged for a ‘what’s in a name tree’ to be made for the nursery, which was made from wood and artistically designed on the wall. Children and families were encouraged to think about their own names and attach a photograph and a description of the meaning of their names, in the shape of a leaf. This was rapidly taken up by children and families, and practitioners saw this as a positive development in staff knowing more about the children and families. Thus, the project evolved from a more descriptive or natural-science investigation, to one that had social implications. It influenced changes in the nursery by direct asks from the children—to have climbing trees—as well as inspiring adults to use the symbolism of trees to further build relationships with children and families. The impacts were built locally, and continue to expand as we write this article.

One of the reported benefits of child-led research, if considered a form of participation, is its temporal and substantive boundaries (Tisdall 2017). The adult academic researcher, Kay, was very concerned, from past experience, to consider how to bring the project to a satisfactory end for all, to ensure that the child researchers celebrated their achievements and had obtained the outcomes they wanted. This focus on ending is not sought for in a Froebelian approach. It was neither a concern for Emma, the adult facilitator, nor was it expressed by the child researchers—they just wanted to continue with their research. They reported being very motivated and enjoying the accumulating documentation of their investigations in the nursery display, and appreciated the growing book of their research journey and findings and the wider sharing of their research with the nursery community. For example, in June 2022, Adaline reflected in a mind-mapping discussion that she enjoyed climbing trees the most, and “We haven’t finished researching yet, we can still keep doing it”. The first phase, to some extent, concluded, but only because of the rhythm of the nursery and school year: school holidays meant that many staff and children were away from the end of June for weeks, and some children from the research group left the nursery in August to go to school. Some children were then interested in continuing onto phase 2, with a new research focus.

This potential of ‘never ending’ has the risk of the research findings not being suitably analysed, synthesised, or consolidated—yet the reflective nature of Froebelian practice included in the child-led research, and its multi-modal methods of documentation, did meet many of those objectives. The nursery’s ‘lived stories’ with children built on the children’s own views and expressions, as described above. This provided a kind of analytical synthesis, involving both the child researchers and supporting adults, and a conclusion. The public display provided a form of validation of the findings. Children spent time reflecting on the research and contributing to a play festival session and conference presentation. As with the other elements presented above, the unfolding of the process did, in fact, deliver on many of the more ‘traditional’ stages of research, but within a Froebelian approach.

In summary, this experience of child-led research questioned several assumptions of child-led research because of the Froebelian approach to children’s participation. Rather than struggling to find a research topic, cycles of listening, reflecting and discussing led to children easily finding a research focus and gradually developing their research methods. Unlike the World Vision definition, the children were not primarily motivated to undertake the research because they wanted to make an impact. They were primarily motivated by their own learning and by sharing that learning with others, combining both pedagogy and research. But, in due course, their research had discernible impacts at their nursery. Neither the children nor the adults perceived the need for a definite end to the project, although the external rhythms of school attendance and holidays led to a pause. Thus, this phase showed an arc of research design, processes and conclusions, which differed in key ways from other child-led research.

3.2. The Roles of Adults and Children

For most advocates of child-led research, an essential component is that adults are not the leaders of the research (see above). This is an essential component because it challenges ‘traditional’ intergenerational relations, where the adult has the power to carry out the research and children, at best, are participants in the research. Child-led research is often promoted from the perspective of childhood studies and/or children’s rights, recognising children as social actors and as having competency and being able to be agentic (e.g., Dahl 2014; Dixon et al. 2019; Wyness 2019). Further, strong claims are often made for child-led research, as an opportunity to ‘empower’ children (Anselma et al. 2020; Graham et al. 2017) and to promote their rights to have a say in matters that affect them, whether that be in their communities, services or policy (Dixon et al. 2019; Pavarini et al. 2019). For the child-led research at the nursery, the practitioner Emma was a facilitator, helping out with the practicalities of going out of the nursery for research fieldtrips, locating resources for children, and instigating conversations and reflections at times (e.g., at the start of the project, on what research is, or following up on a child’s idea for another research cycle).

However, in child-led research generally, there is a discernible assumption that adults, and particularly adult researchers, are the holders of knowledge, expertise and skills on research and its methods. The seminal work carried out by Kellett and colleagues (Kellett 2005) on child-led research resulted in a curriculum for children, taught across several sessions. Similarly, the ever-growing number of toolkits (e.g., Brady and Graham 2022) going through social research and methods, are available for training children and young people.

As described above, Froebelian principles do not position adult supporters of children’s learning in this way: adults are enablers, rather than trainers. Working within the nursery was thus a challenge to this assumption of adult researchers as the holders of research methods knowledge which was to be transmitted to potential child researchers. Further, because of COVID-19 restrictions on carrying out face-to-face research, the adult academic researchers, such as Kay, were not as present at the nursery, as had been originally planned. Emma was supported largely remotely, on the child-led research, with frequent meetings to discuss learning and potential next steps with the adult academic researchers. Thus, efforts were made to support Emma in her key role as research facilitator. But it was not Emma’s practice, nor arguably true to Froebelian principles, to provide more didactic input. Instead, Emma described herself in her reflective interview as a ‘co-researcher’ with the children: “I feel like a co-researcher because there are lots of things that I have learned alongside children, or with them and through them.” Emma explained she did not know much about trees prior to the project, and that she learned a great deal from children during this project. She positioned herself in her reflective interview as a more ‘junior’ research team member, where the children designed and implemented the research, but she learnt with them.

In this project, Emma and other practitioners had two further research roles. The first was documenting. In part, this fits within the Froebelian pedagogy, where documenting in various ways—mind maps, videos, lived stories—are used for reflective learning, sharing learning with children and families, to value people’s perspectives and views. What differed about the child-led research, Emma suggested, was the dedication over time to the research, rather than more short-term consultation or recording. Documentation for and with the children then became even more important, to recognise their work, to provide the tools for reflection, and to facilitate children to opt in and out of the research as they wished. This documentation was also important for wider sharing, as reflected by Emma:

This recording of words was particularly needed, because the children’s mark-making did not cover the range of words they used verbally. As stated, various ways of documenting were used, from video or audio recordings to mind maps.I think without the role of the adult, there wouldn’t necessarily be recording of words written down, so that other members of the community could witness or see the data, and so that other professionals like you could read them.

Second, another key role for Emma was relational. The literature on child-led research is filled with children, as well as adults, sharing the importance of the adult facilitator creating safe, trusting and fun spaces for children and child research to take place in (e.g., Oliveras et al. 2018). As children lead busy lives, in the nursery and outside, the adult facilitator could support continuity in the research, so that children could join when they wanted, catch up if they had missed a part, and feel valued and encouraged by all involved. Emma, for example, reflected on how she would mention to children things she remembered them saying before, and then the children would recall what they had said and add more to the topic. This follows Froebelian practices for learning—as well as the cycles of research for this child-led research. Further, this relational role facilitated children to come into the project, including younger children, at different times, so that the core group was supplemented by a range of other interested children.

At least from the adult researchers’ perspectives, other adults became involved in unexpected ways. A person on the Facilities Management staff was a source of information and stimulus for the child researchers, extending their thoughts to trees in other countries—and particularly ones that could lead on to chocolate. This led to comparative aspects of possibilities (what could be grown where?) and connections with food, and further cycles of research. On the tree hunt fieldtrip, children spoke to local adults about trees that interested the children, which led them on to identify types of trees in their communities. This felt serendipitous to Emma and Kay, who were involved, but, on reflection, these interactions need not have been unexpected. Other academic research projects have been iterative, starting with children’s perspectives about who are the important adults, and then seeking to involve these adults as the relevant research informants (e.g., Mitchell 2019).

Over the timeline of the project, the full range of research decisions was undertaken by one or more of the child researchers. As discussed above, the children decided on the topic, decided how they want to research it, researched it, and shared their findings. Their analysis was collective and reflective, with a thoroughness in considering everything that was collected, but not with the highly structured approach that would be recommended in many research analysis textbooks (e.g., Creswell and Creswell 2022). The adult supporters of this child-led research are interested to see how this will be approached in the next phase of child-led research, as a potential frisson with accepted rigorous standards of analysis.

In short, the Froebelian approaches at the nursery illuminated the assumption in most child-led research that adults are the transmitters of knowledge and expertise on research and its methods, and children must be explicitly trained to undertake child-led research. Instead, the facilitating adult Emma) took on two additional key roles for the research process, in documenting and supporting research relationships. Through the cycles of the child-led research, children developed and expanded their methods, and there was collective analysis.

3.3. Inclusive and Exclusive Communication

Any one method will include and exclude certain children (Tisdall 2016), and this proved true for the child-led research. As detailed above, a range of methods were used by children to express their views and to record their findings. However, even this range of methods favoured certain forms of communication or ways of working that could exclude younger children or those who preferred other forms of communication. Emma, for example, noted that no child under the age of 2 was substantially involved in this first phase of child-led research.

The need to develop meaningful research methods for younger children is increasingly recognised in the literature (e.g., Barblett et al. 2022; Palaiologou 2014). While observation (usually by adults) has proven a powerful tool in many research studies with young children (e.g., Blaisdell 2012; Konstantoni and Kustatscher 2016; McNair 2016), there remain hard questions to ask about how fully that can represent children’s ‘views’ because of the power of the observer—what they choose to observe and note down—and the interpreter of these observations (e.g., Barblett et al. 2022). Even if non-verbal methods are used, such as drawing, model making or photographs, childhood research will often invite children to discuss their creations as a subsequent part of the research process, with that discussion becoming the key data for analysis (Clark 2017). This is frequently done so as to privilege children’s own interpretations, perspectives and meanings, over adult analysis, but once again often relies on words and, most frequently, verbal communication. Such an approach can thus exclude younger children, or children who do not wish to, or find it easy to, communicate, verbally and/or in words.

The collective nature of the child-led research in the nursery provided some opportunities to include younger children. For example, the children could share ideas with each other, such as developing and carrying out their survey for their tree hunt, or two children taught others a song they had learnt outside the nursery. Thus, children could build collectively on individuals’ knowledge, expertise and ideas, to develop the group endeavour. This facilitated children with different interests and different communication modes to participate in particular aspects. The collective approach thus extended inclusivity (if not completely) and provided potential for a distributed, team approach to the research, rather than one child carrying all of the research roles throughout. A group approach will entail power dynamics amongst the children, with some children dominating certain aspects. A group approach, though, also offers certain strengths to the research in terms of allowing for individuals to contribute to the collective, in different ways.

As stated above, documentation was a key facet of the project, with documentation by children and Emma. Even with drawings, photographs and videos, the adults reflected that this documentation was unduly reliant on written or spoken communication—words—and did not capture the fullness of the process or children’s role in it. This was a challenge helpfully raised at a recent conference, regarding the project, and one we wish to develop further in the next phases. We note this challenge was made even more difficult when we faced resistance from more academic or adult-focused contexts to recognising the children as researchers, who were well able to present their own research and experiences. The adults on the project were surprised, for example, that children were not allowed to present at one particular conference, which espoused a child-rights focus, despite having the project abstract accepted and the adults having extensive experience supporting children presenting and co-presenting in numerous academic conferences. If child-led research is making a particular contribution by recognising children as knowledge generators, then ensuring ways to share that knowledge inclusively, especially with intergenerational audiences, remains a necessity for our future phases.

In summary, this first phase of child-led research shows the potential of including a wide range of children, with different communication preferences, in collective research. Nonetheless, it also highlights the dominance of words, in at least these forms of research, which is likely to exclude younger children. It further raises dilemmas about how to share the research process and findings beyond words, particularly when child researchers are prohibited from attending certain key adult spaces for dissemination.

4. Conclusions

Child-led research is becoming more common. For its proponents, it can improve the quality of research, particularly on topics related to children: children can be better placed to identify the research focus and the methods to engage their peers, and to draw out the relevant findings (Ansell et al. 2012; Törrönen and Vornanen 2014). A very large amount of literature documents the benefits for the child researchers, in their own learning and skills development (Anselma et al. 2020; Cuevas-Parra 2018; Graham et al. 2017). Child-led research is promoted as an emancipatory practice, recognising children’s rights to participate; it is a form of epistemic justice (e.g., Cheney 2018; Thomas 2021), and has demonstrably impacted on policy and practice across a host of contexts (Houghton et al. 2023). But, as stated above, its critics doubt its claims to being research: they state that children are unlikely to have the specialist skills to carry out the research or to take on its responsibilities. It tends to be labour-intensive, requiring time and other resources, and it has elements of exclusion (e.g., children who do not want to invest their time) (Nairn et al. 2006).

Acknowledging these debates, our experiences of trialling child-led research led to three reflections to conclude this article: who knows how to carry out research; what research is for; and our modes of research communications. These reflections are developed below.

First, a key aspect of child-led research is that children lead on research decisions, rather than adults. From there, the literature has a range of ways that adult roles are described. Emma’s description as a co-researcher is similar to the educators supporting young children, reported by Barblett and colleagues, positioned as an “authentic novice … someone who is honestly hoping to learn from children” (Barblett et al. 2022, p. 8).4 Kellett (2010) notes that adults can be the research assistants for the child researcher, taking on such tasks as transcribing interviews and data entry, which matches [name of early years practitioner]’s role in documenting the child-led research and providing practical resources. Where this child-led research differed was the approach to knowledge of research methods and skills.

Whereas Kellett and colleagues’ approach, amongst others, is to provide a curriculum of research methods training, this was not an approach conducive to Froebelian pedagogy, and particularly Emma’s approach as a practitioner. Instead, a slow pedagogical approach enabled children’s time, pace and rhythm for their ideas to be heard (Clark 2023b; McNair 2023). As Froebel advocated, “every child needed their own time and space to develop their thinking” (Solly 2016, npn) and opportunities for “causing thought” (Bruce 2021, p. 147). A slow pedagogical approach encourages children to revisit their ideas and creations, places and stories, and creates opportunities for children to go deeper in their learning. Support is given for time for observation, listening, reflection and documentation (Clark 2023a, npn). It was important to Emma that children were unhurried in their research, and that they were offered opportunities to think deeply about what matters most to them; accordingly, a slow unfolding took place, which built on children’s own slow, developing knowledge of research. The Froebelian pedagogy of this early years setting facilitated children to build their own research knowledge, design and skills.5 Child-led research is frequently motivated by a childhood studies’ and children’s rights’ approach to recognising children as social actors, having competency and able to express agency (e.g., see Horgan and Kennan 2022). Yet, the unfolding of this child-led research with younger children illuminates under-explored tensions in the childhood literature, in its assumptions that adults’ knowledge needs to be transmitted to children, regarding how to undertake research properly. This suggests a more technical or mechanist understanding of research methods and skills, and one more conducive to being ‘taught’. The Froebelian conceptualisations of children as independent, creative learners, where adults enable their learning, provide an alternative to these assumptions.

Second, this child-led research questioned what the research was for. As mentioned above, the literature is filled with findings that children can gain many individual benefits from being involved in child-led research. That such individual benefits are documented for children, in ways that would not be documented for adult researchers, is telling in itself: is child-led research positioned as a pedagogical, learning opportunity for individual children, rather than a contribution to knowledge generation? (see also Kim 2017 and Graham et al. 2017). The child researchers were enthusiastic about, and motivated by, their own learning, which points to the pedagogical. They were also keen to share their knowledge from their investigations with others, which might fit definitions of social research, as discussed above. While the definitional boundaries of social research are contestable and permeable, as much interest might be found in what naming something as ‘research’ is doing, claiming, positioning and justifying.

The process itself fits within Froebelian pedagogy, which is about ‘living with our children’, and which is not fixated on closure, outcomes or endings, but is rather a continuous unfolding. This provides a tension with much formal research, which has ending phases of research design, which include synthesis, findings and dissemination (and, hopefully, impact). It does fit within the cycles common to action research (McMellon and Mitchell 2018). It is potentially sustainable, as the child-led research could become part of what the nursery does, with practitioners such as Emma continuing to support this process.

Such an approach is not only testing for research, but also has pedagogical implications for early years settings. For example, Emma thought other practitioners or early years settings that were focused on (adult) structure and timetables would find it difficult. To be child-led, the practitioner had to be willing to wait for the children to determine the structure and the timing. During the child-led research journey, Emma sought to follow children’s interests and respond to their inquisitive nature, which will be promoted as they ask more and more questions. Like all researchers, children and adults alike, questioning encourages the researchers to formulate further questions. But practitioners still have a role, offering “freedom with guidance”, as children communicate their on-going ideas and further ideas for research (Bruce 2021, p. 117).

As Thomas (2021) comments, the context for child-led research matters. Childhood and children’s rights studies can be negative towards the constraints of formal schooling, critiquing the surveillance of children, the ignoring of their rights, and didactic forms of teaching (Quennerstedt and Moody 2020). Graham and colleagues (Graham et al. 2017) note the disadvantages of child-led research undertaken in schools, which can promote ‘education norms’, where children perceive the research as school work in which they have to participate and have little power over. The World Vision definition arose from children undertaking their research within an advocacy-related NGO setting, which may have particularly influenced the children’s emphasis on their research having an impact. In this early years setting, the child-led research was influenced by Froebelian pedagogy and its slow pedagogy, which was neither like school nor an NGO, and followed where the children’s interests went. In itself, this child-led research tests a research paradigm with boundaries of time and resources, the similarities and differences between research and learning, and the current fixations with research impact.

Third, all research methods arguably include or exclude certain forms of communication, and thus participation (see McDonagh and Bateman 2012), and we found this in this child-led research. Emma, in particular, reflected that children under the age of two were not substantially involved in the research. While a range of methods and documentation were used, there was a leaning on expressions through words, whether written down or verbalised, which could exclude children who did not communicate in these ways. Further, the fixation on words did not seem to express fully the child-led research process when shared with wider audiences, even with the showing of videos and explanations from the child researchers. This shone a light on how much the team’s ways of working—including their understandings of research—relied on words. This reflection has led the next phase of child-led research to consider possibilities for wider inclusivity, with younger children and others who have different communication preferences.

More conceptually, the fixation on words epitomises a particular view of knowledge, how it is generated, how it is understood, and how it can be shared. Decolonisation is providing a substantial challenge to Global North assumptions about knowledge, including how knowledge is created and represented, which presume to be universal but in fact are historically and problematically contingent (e.g., Kurtiş and Adams 2017). This leads to Hall and Tandon critiquing higher education institutions today, for excluding “many of the diverse knowledge systems in the world, including those of Indigenous peoples and excluded racial groups, and those excluded on the basis of gender, class or sexuality” (Hall and Tandon 2017, p. 6). We could add exclusions on the basis of age, and particularly of children of younger ages, to the decolonisation critique.

This perhaps goes to the crux to the debates about child-led research: it is challenging intergenerational and professional power, where claims to ‘scientific’ knowledge and skills are held by adults, and particularly elite adults. It goes to why activities such as we undertook use the discourse of research, rather than, say, co-production or participation, because they are making claims to the legitimacy and credibility of such scientific research (see Tisdall 2021 for further discussion). It also asks us to renew our questions about what research is, what it is for, and how it can be undertaken, and invites us to de-centre our assumptions that are not only based on Global North assumptions, on but adult-dominated ones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C., L.J.M. and E.K.M.T.; methodology E.C., L.J.M. and E.K.M.T.; formal analysis E.C. and E.K.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation—E.K.M.T.; writing—review and editing, E.C. and L.J.M.; funding acquisition, L.J.M. and E.K.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Froebel Trust. The article was further influenced by the projects: ‘Safe, Inclusive and Participative Pedagogy’ (ES/T004002/1) and the support of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) is gratefully acknowledged; ‘International and Canadian Child Rights Partnership’ supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh (protocol code KYIS29072021, 31 August 2021) and the City of Edinburgh Council (no number, 26 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all children involved in the study, and their parents. Such consent included publications as a result of the study. Parents provided written consent, while children provided verbal and ongoing consent, with the right to withdraw throughout.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the child researchers—Ada, Adaline, Ailish, Alexander, Anokh, Arta, Aomi, Ayla, Aysel, Brodie, Cleo, Diogo, Éamann, Emma, Ferdia, Finlay, Flynn, Keira, Laurie, Levi, Mara, Marcel, Maria, Mathilda, Misha, Moa, Niamh, Norah, Orran, Ossi, Pip, Teddy, Rex, Rocco, Ruben, Sorley—and other nursery staff, to our learning from this re-search. While due to other work commitments she is not an author on this article, we want to acknowledge the contributions of Sumei Gan, who provided such valuable consolidation and review of this first phase as part of her MSc dissertation. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | For more information, see project website https://www.froebel.ed.ac.uk/ (accessed on 2 December 2023). |

| 2 | Note that the phrase ‘child researchers’ is used in this article, based on the request from the researchers with whom we have been involved. The child researchers preferred this description, because both aspects of that identity were important to them: they were children and they were researchers. |

| 3 | For example, the UKRI Economic and Social Research Council has an impact toolkit for those applying for and receiving funding: https://www.ukri.org/councils/esrc/impact-toolkit-for-economic-and-social-sciences/ (accessed on 2 December 2023). |

| 4 | In turn, Barblett and colleagues were referring to Clark, A. 2010. Young children as protoganists and the role of participatory, visual methods in engaging multiple perspectives. American Journal of Community Psychology 546: 115–23. |

| 5 | A reviewer of this article pointed the authors to Stengers’ work on ‘slow science’ (e.g., Stengers 2018). We think this has much potential—for example, Conway (2018) notes how Stengers calls for the rethinking and reworking of the binary opposition scientist/non-scientist. To do it justice, we propose to consider this in a further article developing both ideas of slow pedagogy and of slow science. |

References

- Ansell, Nicola, Elsbeth Robson, Flora Hajdu, and Lorraine van Blerk. 2012. Learning from young people about their lives: Using participatory methods to research the impacts of AIDS in southern Africa. Children’s Geographies 10: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselma, Manou, Mai Chinapaw, and Teatske Altenburg. 2020. Not Only Adults Can Make Good Decisions, We as Children Can Do That as Well. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barblett, Lennie, Francis Bobongie-Harris, Jennifer Cartmel, Fay Haydley, Linda Harrison, Susan Irvine, and Leanne Lavina. 2022. ‘We’re not useless, we know stuff!’ Gathering children’s voices to inform policy. Australian Journal of Early Childhood 48: 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaisdell, Caralyn. 2012. Inclusive or exclusive participation: Paradigmatic tensions in the Mosaic approach and implications for childhood research. Childhoods Today 6: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones, Caroline, and Julie Taylor. 2015. Engaging with children as co-researchers: Challenges, counter-challenges and solutions. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Louca-Mai, and Berni Graham. 2022. The Young Researcher’s Guidance and Toolkit. Available online: https://researchprofiles.herts.ac.uk/en/publications/young-researchers-guidance (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Tina. 2021. Friedrich Froebel: A Critical Introduction to Key Themes and Debates. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, Kristen. 2018. Decolonizing Childhood Studies. In Reimagining Childhood Studies. Edited by Spyros Spyrou, Rachel Rosen and Daniel Thomas Cook. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Alison. 2017. Listening to Young Children: A Guide to Understanding and Using the Mosaic Approach, 3rd ed. London: National Children’s Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Alison. 2023a. Alison Clark’s Slow Pedagogy: How to Take Your Time with Mealtimes. London: Nursery World. Available online: https://www.nurseryworld.co.uk/features/article/alison-clark-s-slow-pedagogy-how-to-take-your-time-with-mealtimes (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Clark, Alison. 2023b. Slow Knowledge and the Unhurried Child. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Tara M., Lucy Jamieson, Laura H. V. Wright, Irene Rizzini, Amanda Mayhew, Javita Narang, E. Kay M. Tisdall, and Monica Ruiz-Casares. 2020. Involving Child and Youth Advisors in Academic Research About Child Participation. Children and Youth Services Review 109: 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, Philip. 2018. Another Science is possible by Isabelle Stengers. In Society and Space. Available online: https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/another-science-is-possible-by-isabelle-stengers (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Coppock, Vicki. 2011. Children as Peer Researchers: Reflections on a Journey of Mutual Discovery: Children as Peer Researchers. Children & Society 25: 435–46. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2022. Research Design, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Parra, Patricio. 2018. Exploring Child-Led Research: Case Studies from Bangladesh, Lebanon and Jordan. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. Available online: https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/33057 (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Cuevas-Parra, Patricio, and E. Kay M. Tisdall. 2018. Child-Led Research: From Participating in Research to Leading It. New York: World Vision International. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Parra, Patricio, and E. Kay M. Tisdall. 2019. Child-Led Research: Questioning knowledge. Social Sciences 8: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Tove I. 2014. Children as Researchers. In The Sage Handbook of Child Research. Edited by Gary B. Melton, Asher Ben-Arieh, Judith Cashmore, Gail S. Goodman and Natalie K. Worley. London: Sage, pp. 593–618. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Jo, Jade Ward, and Sarah Blower. 2019. They sat and actually listened to what we think about the care system. Child Care in Practice 25: 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, Myfanwy. 2011. Pockets of Participation: Revisiting Child-Centred Participation Research. Children & Society 25: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Anne, Catharine Simmons, and Julia Truscott. 2017. ‘I’m More Confident Now, I Was Really Quiet’: Exploring the Potential Benefits of Child-Led Research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Budd L., and Rajesh Tandon. 2017. Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education. Research for All 1: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, Martyn. 2017. Childhood Studies: A sustainable paradigm? Childhood 24: 113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Chae-Young Kim. 2021. Child-led research, children’s rights and childhood studies—A reply to Thomas. Childhood 28: 200–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, Deirdre, and Danielle Kennan, eds. 2022. Child and Youth Participation in Policy, Practice and Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, Claire. 2015. Young People’s Perspectives on Participatory Ethics. Child Abuse Review 24: 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, Claire, Julia Mazur, Layla Kansour-Sinclair, and E. Kay M. Tisdall. 2023. Being a young political actor. In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation. Edited by Afua Twum-Danso Imoh, Nigel Patrick Thomas, Clare O’Kane and Barry Percy-Smith. London: Routledge, pp. 222–29. [Google Scholar]

- James, Allison, and Alan Prout. 1990. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood, 1st ed. London: The Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kellett, Mary. 2005. How to Develop Children as Researchers. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kellett, Mary. 2010. Small Shoes, Big Steps! Empowering Children as Active Researchers. American Journal of Community Psychology 46: 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Kanamik K., and Md. Mohsin Reza. 2022. Social Research: Definitions, Types, Nature, and Characteristics. In Principles of Social Research Methodology. Edited by M. Rezaul Islam, Niaz A. Khan and Rajendra Baikady. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Chae-Young. 2016. Why research by children? Children & Society 30: 230–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chae-Young. 2017. Participation or Pedagogy? Ambiguities and Tensions Surrounding the Facilitation of Children as Researchers. Childhood 24: 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantoni, Kristina, and Marlies Kustatscher. 2016. Conducting ethnographic research in early childhood research: Questions of participation. In The Sage Handbook of Early Childhood Research. Edited by Ann Farrell, Sharon L. Kagan and E. Kay M. Tisdall. London: Sage, pp. 223–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtiş, Tuğçe, and Glenn Adams. 2017. Decolonial Intersectionality: Implications for Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. In Intersectional Pedagogy: Complicating Identity and Social Justice. Edited by Kim A. Case. New York: Routledge, pp. 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liabo, Kristin, and Helen Roberts. 2019. Coproduction and Coproducing Research with Children and Their Parents. Archives of Disease in Childhood 104: 1134–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebschner, Joachim. 1992. A Child’s Work: Freedom and Play in Froebel’s Educational Theory and Practice. Cambridge, UK: Lutterworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarry, Melanie. 2012. Who Benefits? A critical reflection of children and young people’s participation in sensitive research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 15: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, Janet E., and Belinda Bateman. 2012. Nothing about us without us: Considerations for research involving young people. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Education and Practice Edition 97: 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMellon, Christina, and Mary Mitchell. 2018. Participatory Action Research with Young People. In Building Research Design in Education. Edited by John Ravenscroft and Lorna Hamilton. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 173–96. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, Lynn J. 2016. Rules, Rules, Rules and We’re Not Allowed to Skip. Ph.D thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. Available online: https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/22942 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- McNair, Lynn J. 2023. Slow Pedagogy: Time, Pace and Rhythm. Available online: https://www.communityplaythings.co.uk/learning-library/articles/slow-pedagogy (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- McNair, Lynn J., Caralyn Blaisdell, John M. Davis, and Luke Addison. 2021. Acts of pedagogical resistance: Marking out an ethical boundary against human technologies. Policy Futures in Education 19: 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, Samia, and Mary Kellett. 2015. Child-led research in the context of Australian social welfare practice. Child & Family Social Work 20: 387–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Mary. 2019. Reimagining child welfare outcomes. Child & Family Social Work 25: 211–20. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Bloch, Christoph, and Johann Kranz. 2015. A Framework for Rigorously Identifying Research Gaps in Qualitative Literature Reviews. International Conference on Information Systems. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301367526.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Mutch, Carol. 2017. Children researching their own experiences. Set: Research Information for Teachers 2: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, Karen, Judith Sligo, and Claire Freeman. 2006. Polarizing Participation in Local Government. Children, Youth and Environments 16: 248–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveras, Carlo, Lucie Cluver, Sarah Bernays, and Alice Armstrong. 2018. “Nothing About Us Without RIGHTS”—Meaningful Engagement of Children and Youth. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 78: S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiologou, Ioanna. 2014. ‘Do We Hear What Children Want to Say?’ Ethical Praxis When Choosing Research Tools with Children Under Five. Early Child Development and Care 184: 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarini, Gabriela, Jessica Lorimer, Arianna Mazini, Ed Goundrey-Smith, and Ilina Singh. 2019. Co-producing research with youth. Health Expectations 22: 743–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quennerstedt, Ann, and Zoe Moody. 2020. Educational Children’s Rights Research 1989–2019: Achievements, Gaps and Future Prospects. The International Journal of Children’s Rights 28: 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, Kathryn. 2016. Following in Froebel’s Footsteps. Early Years Education. Available online: https://www.earlyyearseducator.co.uk/features/article/following-in-froebel-s-footsteps (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Spyrou, Spyros. 2018. Disclosing Childhoods: Research and Knowledge Production for a Critical Childhood Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Stengers, Isabelle. 2018. Another Science is Possible. Translated by Stephen Muecke. Cambridge, UK: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Nigel Patrick. 2021. Child-led Research, Children’s Rights and Childhood Studies: A Defence. Childhood 28: 186–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, E. Kay M. 2016. Participation, Rights and ‘Participatory Methods’. In The Sage Handbook of Early Childhood Research. Edited by Ann Farrell, Sharon L. Kagan and E. Kay M. Tisdall. London: Sage, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall, E. Kay M. 2017. Conceptualising children and young people’s participation: Examining vulnerability, social accountability and co-production. International Journal of Human Rights 21: 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, E. Kay M. 2021. Meaningful, Effective and Sustainable? Challenges for children and young people’s participation. In Young People’s Participation: Revisiting Youth and Inequalities in Europe. Edited by Maria Bruselius-Jensen, Ilaria Pitti and E. Kay M. Tisdall. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 217–34. [Google Scholar]

- Törrönen, Maritta Lea, and Riitta Helena Vornanen. 2014. Young People Leaving Care: Participatory Research to Improve Child Welfare Practices and the Rights of Children and Young People. Australian Social Work 67: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2023. SDG Resources for Educators—Quality Education. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education/sdgs/material/04 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- World Vision International. 2015. Children and Young People-Led Research Methodology. Available online: https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/WV-CAY-Led-Research%20Methodology-03–11-2016%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- World Vision International. 2017. Child-Led Research: An Essential Approach for Ending Violence against Children. Available online: https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/WV-Child-led-Research-03-03-2017.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Wyness, Michael. G. 2019. Childhood and Society, 3rd ed. London: Red Globe Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).