Abstract

Bullying is a phenomenon that afflicts millions of students around the world, severely harming their emotional and psychological well-being. In response to this challenge, the TEI program (Tutoría Entre Iguales or Peer Tutoring) has been developed as a bullying prevention strategy, aiding students in acquiring social skills and emotional strategies for conflict resolution. The purpose of this research is to examine social skills and empathy among different actors involved in bullying (non-involved, victim, bully, and bully-victim) among secondary school students and to evaluate the impact of the TEI program on the development of relational competencies. A comparative, ex post facto study was conducted in three schools where the TEI program has been implemented (TEI schools) and three where it has not (non-TEI schools). A total of 738 secondary school students (ESO) participated in the study, using a standardized questionnaire to evaluate their perception of bullying. The results of this study demonstrate higher levels of assertiveness and empathy in the non-involved and victim groups. However, lower levels of conflict resolution skills were found in the bully-victim group. In TEI schools, a higher percentage of students not involved in bullying and a lower percentage of bully-victims were observed. Additionally, students in TEI schools scored higher in assertiveness, conflict resolution skills, social skills, and empathy. These findings highlight the importance of developing students’ relational competencies and implementing strategies for bullying prevention to create a safe, healthy, and positive learning environment in schools.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of bullying in schools poses significant challenges with numerous and severe consequences for all involved parties (Armitage 2021; Bochaver 2021; Boulton and Underwood 1992; Le Menestrel 2020). In the context of school bullying, three fundamental roles can be identified: the aggressor, the victim, and the observers or spectators (Bisquerra et al. 2014; Cantera-Espinosa et al. 2021). These three elements constitute what is known as the “violence triangle” (Ortega 1997; Del Rey and Ortega 2007). Unfortunately, this reality adversely affects students, creating an adverse environment that is detrimental to emotional well-being and social integration, with severe consequences for all involved (Costa et al. 2020; Estévez et al. 2019).

There are numerous prevention and intervention programs against school bullying (Sainz and Martín-Moya 2023). Some of the most prominent internationally include the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (Olweus 1993), the ABC Program (O’Moore and Minton 2004), Kiva (Salmivalli et al. 2011), Be-Prox (Alsaker and Valkanover 2012), and the TEI program (González-Bellido 2015).

Research indicates that effective programs involve the entire school community, with peer students playing a pivotal role in preventing bullying (Ttofi and Farrington 2012).

One of the principal characteristics of the TEI program is that it involves the entire school community, and the joint efforts of all members of the community are the key to success (González-Bellido 2021). In the TEI program, older or more experienced students, called tutors, undergo training to support and guide their younger peers, known as tutees. The program’s innovative dual-triangle intervention creates a strong emotional support network, with students serving as emotional tutors for lower-grade peers. In bullying situations, students approach their designated emotional tutor, who, if necessary, initiates a dialogue between the victim’s tutor and the alleged aggressor’s tutor to explore resolutions. If mediation fails, the TEI program coordinator, a teacher, actively intervenes in conflict resolution. This intervention mechanism aims to encourage both vertical and horizontal interaction, allowing the involved parties to collaborate initially before resorting to higher authorities (González-Bellido 2015).

Peer tutoring is not only a strategy against bullying but also a way to build an inclusive and collaborative school culture. This approach promotes crucial values like empathy and respect, offering students a space for understanding and strengthening emotional bonds, thereby creating a more cohesive and inclusive school community (González-Bellido 2015).

The effectiveness of the TEI program in reducing instances of bullying and improving the school environment has been demonstrated by recent research (Ferrer-Cascales et al. 2019; Sainz et al. 2023). Furthermore, it has been found that the TEI program has a positive impact on the personal well-being of students who show higher levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy in schools where the program has been implemented (Soto-García and Sainz 2023).

It is well-established that the lack of effective social skills is closely linked to dysfunctional personal relationships and poor social integration, potentially leading to instances of bullying (Castro et al. 2017; Ferrel et al. 2015; González-Vallejo 2015; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al. 2021).

Research examining the link between social skills and bullying suggests that individuals with greater or more effective social skills are associated with fewer occurrences of bullying (Marquina Candia 2018; Mendoza and Maldonado 2017; Sousa et al. 2023). The deficit in social skills is linked to involvement in episodes of bullying, with non-involved students demonstrating higher social skill levels (Mendoza and Maldonado 2017). This deficiency in social skills also predisposes students to be victims or passive observers of bullying. Some studies emphasize the role of effective social skills as a defense against bullying (Dueñas Buey and Serna Varela 2009; Hussein 2013), highlighting the crucial role of assertiveness in expressing thoughts and feelings clearly and respectfully (De la Plaza Olivares and Ordi 2019).

Essential interpersonal skills encompass empathy, defined as the ability to understand and adopt the perspective of another (Tortosa-Jiménez 2018). Empathy is crucial in establishing robust and meaningful relationships with others and is considered an essential aspect of healthy or positive psychological and emotional development (Moya-Albiol 2014). Thus, empathy involves the capacity to comprehend the feelings of others, which is a critical factor in managing the emotional and social landscape of adolescence (Jolliffe and Farrington 2006b).

It Is necessary to distinguish between affective and cognitive empathy to identify specific deficits in the various roles involved in bullying (Van Noorden et al. 2015). Cognitive empathy refers to the ability to understand and adopt the perspective of others, while affective empathy involves experiencing and sharing the experiences and emotions of others (Jolliffe and Farrington 2006b).

Several studies (Ang and Goh 2010; Bhau and Tung 2020; Utomo 2022) show an inverse relationship between both affective and cognitive empathy and bullying. In the study by Noorden et al. (2017), they note a lower empathy perception for bullies, victims, and bully-victims compared to uninvolved peers. Salavera et al. (2021) found victims had higher empathic concern, but both victims and bullies showed similar results in affective and cognitive empathy. Deficits in cognitive empathy may contribute to aggressors’ lack of understanding, while deficits in affective empathy may hinder experiencing and sharing victims’ emotions (Van Noorden et al. 2015).

Pro-social attitudes and empathy, identified by Moreno-Bataller et al. (2019), play a crucial role in preventing antisocial behavior. Studies consistently associate a lack of empathy with bullying and aggressive behavior in children and adolescents (Bhau and Tung 2020; García-Visús et al. 2021; Jolliffe and Farrington 2006b; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al. 2021; Stavrinides et al. 2010; Utomo 2022; Van Noorden et al. 2015). The proper development of empathy is not only linked to understanding and reflecting on emotions but is also integral to positive conflict resolution and pro-social behavior (Merino-Soto and Grimaldo-Muchotrigo 2015).

Young people displaying pro-social attitudes and behavior have higher levels of empathy than those who are the perpetrators or victims of bullying (Oliva-Delgado et al. 2011). The lack of empathy on the part of aggressors is an important factor within the phenomenon of bullying in schools, given that in the majority of cases, the aggressor is unable to put themselves in the place of the victim or understand their feelings (Armero et al. 2011; Van Noorden et al. 2015). According to Albaladejo-Blázquez et al. (2016), aggressors have a maladaptive or dysfunctional profile, which is associated with a lack of empathy, aggressive behavior, difficulty in following rules, and school absenteeism, among others. Additionally, Thornberg and Jungert (2013) note that basic moral sensibility, referring to the capacity of a person to feel empathy and compassion for another may influence the response of spectators or bystanders.

Intervention programs based on social skills and empathy have been shown to improve the social interactions of victims and enhance their quality of life in school by reducing levels of victimization (Da Silva et al. 2018). Thus, research has demonstrated that both social skills and empathy act as protective factors against school bullying (Hussein 2013; Ramírez-Coronel et al. 2020; Stan and Galea 2014; Van Noorden et al. 2017).

The TEI program is based on the conviction that fostering positive and pro-social attitudes and behavior is essential to eradicating this type of violence and other relational conflicts during adolescence (Cañas-Pardo 2017; Moya-Albiol 2014). The peer tutoring strategy is based on mutual peer support among schoolmates; that is, working to build closer relationships and reinforce feelings of empathy (Álvarez and González 2008).

The TEI program stands out as a unique and highly effective approach in the realm of peer mentoring. This program distinguishes itself by its emphasis on emotional connection and empathy between tutors and tutees, creating an atmosphere of mutual support and promoting comprehensive socioemotional development. The peer-to-peer relationship fosters a sense of belonging and collaboration. The emphasis on emotional connection not only makes a significant difference but also constitutes the core of TEI’s success. By promoting relationships based on empathy, a deeper bond is formed between tutors and tutees, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of individual needs and fostering a learning environment where trust and respect are paramount. Through peer mentoring, emotional and social aspects are addressed, enabling students not only to progress academically but also to develop valuable interpersonal skills for life (González-Bellido 2015, 2021).

In this context, the research question posed in this study is as follows: does the TEI program have a significant impact on the development of social skills and empathy?

In response to this question, this study aims to assess the impact of the TEI program on the relational competencies of students. Additional specific research objectives are as follows:

- To observe the levels of social skills and empathy among different roles involved in bullying (non-involved, victim, bully, and bully-victim).

- To compare the level of social skills of students attending TEI schools and non-TEI schools.

- To compare the level of empathy of students attending TEI schools and non-TEI schools.

The research is expected to show a significant relation between bullying and relational variables (Ang and Goh 2010; Castro et al. 2017; Dueñas Buey and Serna Varela 2009; Mendoza and Maldonado 2017), as well as demonstrable benefits from the peer tutoring program in improving the school environment and preventing instances of bullying (Albaladejo-Blázquez et al. 2016; Ferrer-Cascales et al. 2019; García-Visús et al. 2021; Linaje and Cotán Fernández 2020; Martín-Criado and Casas 2019; Sainz et al. 2023). These expectations are presented as the following initial research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

It is expected that students involved in instances of bullying show lower levels of empathy and social skills.

Hypothesis 2.

Students attending a TEI school show higher levels of social skills than students attending non-TEI schools.

Hypothesis 3.

Students attending a TEI school show higher levels of empathy than students attending non-TEI schools.

Hypothesis 4.

A lower incidence of victims and aggressors is expected in educational centers with the Peer Tutoring Program (TEI) compared to those without the TEI (non-TEI).

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve these research objectives, a transversal, descriptive, ex post facto study was conducted using a quantitative methodology. The research consisted of a comparative study of schools implementing the TEI program (TEI schools) and those that did not (non-TEI schools).

The dependent variables in this study are social skills, empathy, and bullying. The independent variable is the type of school depending on the implementation of the TEI program (TEI schools and non-TEI schools).

2.1. Participants

A total of 738 first- to fourth-year ESO (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria) students participated in this study. As shown in Table 1 the sample was fairly evenly balanced in terms of gender, with 388 boys and 350 girls.

Table 1.

Participants by gender and school year.

Participants were selected using an intentional, non-probability sampling method, selecting three schools where the TEI program was implemented and another three schools where the program was not implemented but with similar sociodemographic characteristics in order for the application of the TEI program to be the only significant variable.

The participating schools were located in three autonomous communities of Spain (Comunidad Valenciana, Extremadura, and Castilla y León), and one TEI school and one non-EI school were selected from each community. Thus, the final sample consisted of 338 students from TEI schools and 400 students from non-TEI schools (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants of TEI and non-TEI schools by autonomous community.

The TEI schools participating in this study all had implemented the TEI program for a minimum of two years given that, according to the author of the program (González-Bellido 2015), the TEI requires a period of at least two years to involve the entire school community.

2.2. Instrument

Data were collected using a standard questionnaire that incorporated various scales.

The first part of the questionnaire collected sociodemographic data (gender, age, school year, autonomous community, and school) for the analysis and comparison of the responses.

The phenomenon of bullying in schools was evaluated using the European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire—EBIP-Q (Ortega et al. 2016). This instrument consists of 14 items with 5 response options from 0 (never) to 4 (always) and provides a score on two dimensions of bullying: victimization (α = 0.84) and aggression (α = 0.73).

The Social Skills Evaluation Scale (Escala para la Evaluación de las Habilidades Sociales) (Oliva-Delgado et al. 2011) was used to analyze student perceptions of their own social skills. The scale consists of 12 items with 7 response options: 1—totally false, 2—false, 3—somewhat false, 4—neither true nor false, 5—somewhat true, 6—true, and 7—totally true. The scale provides a global score for student social skills (α = 0.69), as well as specific scores for three dimensions: communication and relational skills (α = 0.74), assertiveness (α = 0.75), and conflict resolution skills (α = 0.80).

The Basic Empathy Scale-BES by Jolliffe and Farrington (2006a), in its validated Spanish version (Villadangos Fernández et al. 2016), was used to evaluate levels of student empathy. The scale consists of 20 items with a 5-option, Likert-type response scale: 1—completely disagree; 2—disagree; 3—neither agree nor disagree; 4—agree; and 5—completely agree. The scale measures two dimensions: affective empathy (α = 0.85) and cognitive empathy (α = 0.79).

3. Procedure and Data Analysis

The questionnaires were administered online using the Jot-form application and using a single link to ensure the anonymity of the responses. The data collection process took place during the academic course 2020–2021. The research project received prior approval from the university research ethics committee, and the consent and authorization of parents and/or legal guardians of participants were requested.

After obtaining the necessary consent, a specific date was scheduled to administer the questionnaire. Before answering the questionnaires, students were thoroughly informed about the purpose of the research project. They voluntarily agreed to participate, with the assurance of anonymity and the confidentiality of their answers, in accordance with the research ethics guidelines of the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, the Universidad de Córdoba, and the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Students completed the questionnaires at school during class time in the presence of their teacher. A member of the research team was also present to address any questions or concerns that the students may have had.

Regarding the data analyses, firstly, we identified the roles of non-involved, victims, bullies, and bully-victims among the participants based on their responses to the EBIP-Q instrument, following the criteria below:

- -

- Non-involved: If participants scored less than 3 on all items in both dimensions (victimization and aggression).

- -

- Victim: If the participant scored 3 or higher on at least one item in the victimization dimension and scored less than 3 on all items in the aggression dimension.

- -

- Bully: If the participant scored 3 or higher on at least one item in the aggression dimension and scored less than 3 on all items in the victimization dimension.

- -

- Bully-victim: If the participant scored 3 or higher on at least one item in both the victimization and aggression dimensions.

To determine the influence of the TEI program on the relational competencies of ESO students, a comparison was made of the scores obtained by students attending TEI and non-TEI schools.

It is important to note that the scores for social variables (social skills and empathy) and all their different dimensions have been converted to a centesimal numeration, from 0 to 100, to facilitate analysis and interpretation.

The data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS STATISTICS suite, version 29, (IBM: Armonk, NY, USA) and the tables and graphs were created with Excel. Parametric tests were conducted (Chi-square tests, ANOVA, and Student’s t-test) to verify the research hypotheses, calculating the effect size with Cohen’s d and eta squared.

4. Results

4.1. Social Skills and Empathy in Different Roles Involved in Bullying

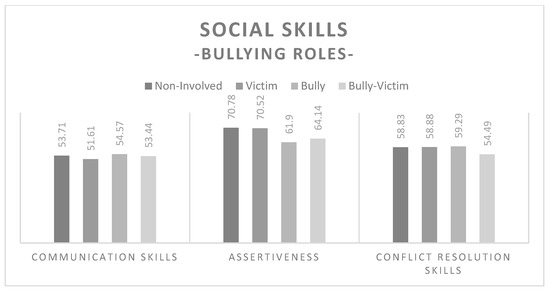

Differences in levels of social variables, such as social skills and empathy, were analyzed based on different roles (non-involved, victim, bully, and bully-victim). Figure 1 displays mean scores in various dimensions of social skills, including communication skills, assertiveness, and conflict resolution skills, for different bullying roles (non-involved, victim, bully, and bully-victim).

Figure 1.

Average scores for social skills in bullying roles.

In the dimension of communication skills, it is observed that mean scores are quite similar across different roles, with victims obtaining the lowest mean score (M = 51.61; SD = 22.77) and bullies obtaining the highest mean score (M = 54.57; SD = 21.04). Regarding assertiveness, non-involved individuals and victims have the highest mean scores (M = 70.78; SD = 19.30 and M = 70.52; SD = 21.58, respectively), while bullies have the lowest mean score in assertiveness (M = 61.90; SD = 21.31).

In the dimension of conflict resolution skills, the mean scores are quite similar across different bullying roles, with participants in the bully-victim role obtaining the lowest mean score (M = 54.49; SD = 22.19).

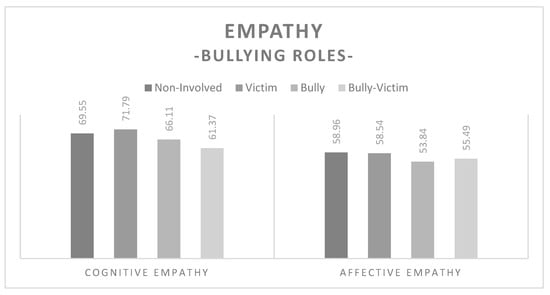

In Figure 2, mean scores in the dimensions of empathy (affective and cognitive) for different bullying roles are depicted. In the dimension of cognitive empathy, victims achieved the highest mean score (M = 71.79; SD = 17.22), while bully-victims recorded the lowest mean score (M = 61.37; SD = 18.41). Regarding affective empathy, participants categorized as non-involved (M = 58.96; SD = 16.49) and victims (M = 58.54; SD = 18.48) obtained the highest mean scores. However, participants categorized as bullies (M = 53.84; SD = 15.42) and bully-victims (M = 55.49; SD = 16.99) recorded the lowest mean scores in affective empathy.

Figure 2.

Average scores for empathy in bullying roles.

In Table 3, descriptive statistics for various dimensions of social skills (communication skills, assertiveness, and conflict resolution skills) and empathy (cognitive and affective) are presented across different bullying roles (non-involved, victim, bully, and bully-victim).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of social skills and empathy according to bullying roles.

ANOVA tests were conducted to examine differences in the dimensions of social skills and empathy among different roles (see Table 4). Regarding the social dimensions of empathy, a statistically significant effect was observed only in the assertiveness dimension (F(3, 726) = 4.603; p < 0.01; η2 = 0.02). In the empathy dimensions, a significant effect was found in cognitive empathy (F(3, 726) = 7.784; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.03) but not in affective empathy (p = 0.127).

Table 4.

ANOVA of social variables according to bullying roles.

To assess significant differences in the assertiveness dimension among different bullying roles, we applied the multiple comparisons test using the Tukey statistic, and the results are presented in Table 5. It can be observed that significant differences in assertiveness exist only between the non-involved and bully-victim roles (t(726) = 2.89; p < 0.05; d = 0.34).

Table 5.

Multiple comparisons among different bullying roles in assertiveness.

We also conducted the multiple comparisons test using the Tukey statistic for the dimension of cognitive empathy. As shown in Table 6, significant differences in cognitive empathy were observed between the non-involved and bully-victim roles (t(726) = 4.27; p < 0.001; d = 0.49), as well as between victims and bully-victims (t(726) = 4.42; p < 0.001; d = 0.59).

Table 6.

Multiple comparisons among different bullying roles in cognitive empathy.

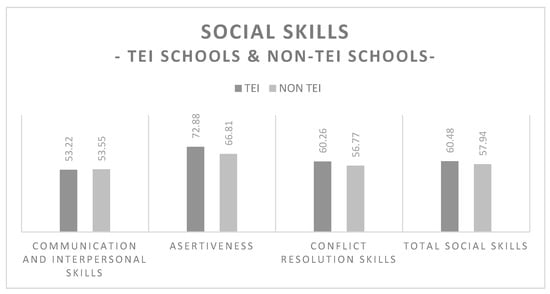

4.2. Differences in Social Skills among TEI and Non-TEI School Students

As shown in Figure 3, the average scores of TEI school students were higher in the dimensions of assertiveness (TEI schools: M = 72.88; DT = 19.60 and non-TEI schools: M = 66.81; DT = 20.22) and conflict resolution skills (TEI schools: M = 60.26; DT = 20.20 and non-TEI schools: M = 56.77; DT = 20.48). The results of the Student’s t-test for independent samples show that these differences are significant for both assertiveness (t(736) = 4.125; p < 0.001; d = 0.305) and conflict resolution skills (t(736) = 2.322; p < 0.05; d = 0.172).

Figure 3.

Average scores for social skills among TEI and non-TEI school students.

For communication and relational skills, the average scores of students of non-TEI schools were slightly higher (M = 53.55; DT = 22.03) than TEI school students (M = 53.23; DT = 24.44). However, the Student’s t-test for independent variables shows that these differences are not statistically significant (p = 0.851).

For social skills, students of TEI schools scored on average higher (M = 60.49; DT = 14.09) than non-TEI schools (M = 57.94; DT = 13.08). The Student’s t-test for independent samples shows these differences are statistically significant (t(736) = 2.545; p < 0.05; d = 0.188). That is, in general terms, it was observed that students from TEI schools have higher levels of social skills compared to students of non-TEI schools.

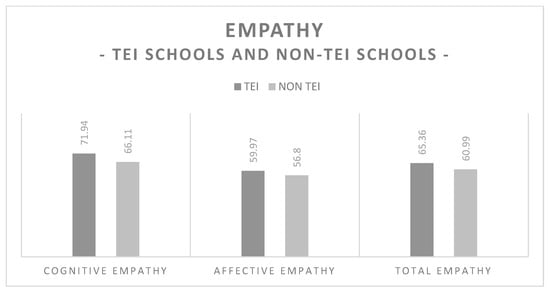

4.3. Differences in Empathy among TEI and Non-TEI School Students

Regarding the differences in levels of empathy among TEI and non-TEI students, (Figure 4) the results show that students of TEI schools scored higher on average than students of non-TEI schools in all dimensions of empathy: cognitive empathy (TEI schools: M = 71.94; DT = 16.18 and non-TEI schools: M = 66.11; DT = 17.04), affective empathy (TEI schools: M = 59.97; DT = 17.58 and non-TEI schools: M = 56.80; DT = 16.17), and total empathy (TEI schools: M = 65.36; DT = 14.79 and non-TEI schools: M = 60.99; DT = 14.67).

Figure 4.

Average scores for empathy among TEI and non-TEI school students.

The Student’s t-test for independent samples shows that these differences are statistically significant in all dimensions: cognitive empathy (t(736) = 4.740; p < 0.001; d = 0.350), affective empathy (t(736) = 2.555; p < 0.05; d = 0.189), and total empathy (t(736) = 4.018; p < 0.001; d = 0.297). Thus, it can be affirmed that students at TEI schools show higher levels of empathy than students at non-TEI schools.

4.4. Roles Involved in Bullying in TEI and Non-TEI Schools

After categorizing participants into different roles involved in bullying (non-involved, victim, bully, and bully-victim), we can observe their incidence in TEI and non-TEI schools. Table 7 presents the results of frequencies and percentages for each category.

Table 7.

Cross-tabulation of bullying roles in TEI and non-TEI schools.

It can be observed that in TEI schools, there is a higher percentage of non-involved students (70.3%) compared to the percentage of non-involved students in bullying in non-TEI schools (64.8%). Additionally, it is also noted that the percentage of bully-victims is higher in non-TEI schools (16.8%) than in TEI schools (7%). After applying the Chi-square test (χ2 = 16.836), it is observed that these differences are significant (p < 0.001).

5. Discussion

This section presents the principal findings of the study and their implications, with the hope of providing insight into how to address the phenomenon of bullying in schools and create a safer and more positive learning environment for students. Drawing on the obtained results and aligning them with the literature review, we can conclude that our first hypothesis, anticipating lower levels of empathy and social skills in students involved in instances of bullying, has found partial support in the findings.

Concerning social skills, the absence of these skills appears to be associated with difficulties in social integration and the onset of bullying cases, corroborating earlier studies (Castro et al. 2017; Ferrel et al. 2015; González-Vallejo 2015; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al. 2021). Although victims display lower scores in communication skills, the differences are not statistically significant in most dimensions compared to the non-involved, bullies, and bully-victims. Surprisingly, bullies exhibit higher scores in communication skills, although these differences are not statistically significant. However, in the assertiveness dimension, differences are significant, with non-involved and victims standing out, which is consistent with earlier studies (Dueñas Buey and Serna Varela 2009).

Regarding empathy, the results suggest more pronounced differences. Victims and non-involved students exhibit higher levels of empathy, while bullies show significant deficits in cognitive empathy, supporting the idea that a lack of empathy is a psychological predictor of bullying (Bhau and Tung 2020; García-Visús et al. 2021; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al. 2021; Utomo 2022; Van Noorden et al. 2015). These variations in empathy underscore the need for personalized intervention approaches.

Although the results do not entirely confirm a generalized decrease in empathy and social skills in students involved in bullying, they do reveal differentiated patterns based on specific roles. Higher levels of empathy and assertiveness are observed in the non-involved and victims of bullying, while bully-victims show lower levels of conflict resolution skills and empathy, and bullies exhibit lower levels of empathy. These findings are in line with previous research indicating that students directly involved in cases of bullying generally lack effective social competencies (Castro et al. 2017; González-Vallejo 2015; Marquina Candia 2018; Mendoza and Maldonado 2017).

Understanding these specific patterns of empathy and social skills can provide valuable insights for designing intervention strategies adapted to different roles and the particular needs of each group, recognizing the complexities and variations present in students’ social skills and empathy. This nuanced understanding underscores the importance of tailored intervention programs to address the multifaceted nature of bullying dynamics in school settings.

Furthermore, we have observed that in educational institutions that have implemented the TEI program, there is a higher percentage of students not involved in bullying and a lower percentage of bully-victims compared to educational institutions without this prevention program, confirming the fourth hypothesis of this study.

The TEI program is a valuable tool that empowers students to be true agents of change in their schools. This bullying prevention strategy works to develop social skills and emotional strategies, empathy, and solidarity while bolstering the feeling of community and belonging in schools. Previous research has confirmed the effectiveness of the program in enhancing the school environment and reducing instances of bullying and cyberbullying (Ferrer-Cascales et al. 2019; Sainz et al. 2023).

The results of our study suggest that the TEI program can have a positive impact on the personal and social development of students, bolstering their capacity to peacefully resolve conflicts and fostering feelings of empathy for others. Students in schools that have implemented the TEI program generally score higher in social skills, especially assertiveness and conflict resolution skills, compared to students in schools that have not implemented the program. This confirms our second research hypothesis. These results are also in line with the findings of previous studies showing that peer support programs are effective in improving the social skills of students (Albaladejo-Blázquez et al. 2016; Ferrer-Cascales et al. 2019).

We also found that students of TEI schools show higher levels of empathy, confirming our third research hypothesis. Here again, these findings confirm those of previous research suggesting that empathy is a psychological predictor of bullying and that aggressors generally have lower levels of empathy (Albaladejo-Blázquez et al. 2016; García-Visús et al. 2021).

Thus, this study confirms that the TEI program empowers students to be models and guides for their peers through the development of social skills and emotional strategies that are effective in resolving conflicts and fostering empathy and solidarity among schoolmates (González-Bellido 2015; Linaje and Cotán Fernández 2020). These results suggest that the TEI program can play an important role in promoting a safe and positive environment in schools and preventing instances of bullying.

6. Conclusions

The phenomenon of bullying poses a significant challenge for adolescents and young people, profoundly affecting their emotional well-being, personal growth, and social integration. This study delves into the social and emotional dynamics that shape the lives of secondary school (ESO) students in the context of the TEI program for bullying prevention.

Our findings underscore the need for ongoing research on the psychological well-being of young people, considering contextual factors such as family life and social environment. Future investigations should explore how family relationships, social support, and school dynamics may act as risk or protective factors in bullying instances, influencing psychological well-being and mental health.

Furthermore, recognizing the co-morbidities of bullying and mental health is crucial. Establishing the relationship between these factors and developing effective strategies to address these issues should be a priority. Training teachers and staff to identify and handle bullying is essential. Empowering educators with the necessary tools not only aids in preventing or mitigating bullying but also provides crucial support to students facing mental health difficulties due to aggression and abuse. Thus, continuous efforts are needed to understand the intricate relationship between bullying and mental health and develop effective intervention strategies.

In the current era dominated by Internet addiction and constant connectivity, understanding the impact of digital behaviors on prosocial and aggressive tendencies becomes paramount. Investigating how virtual experiences influence empathy and aggressive behaviors is crucial for developing preventive and intervention strategies in the context of bullying. The TEI program stands out by addressing both traditional bullying and cyberbullying, aiming to foster a safe online environment and enhance overall well-being in educational settings.

Looking ahead, it is crucial to recognize the need for comparative studies between the TEI program and other bullying prevention initiatives. Such research endeavors would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of the impact of different approaches on reducing bullying and improving educational coexistence. These comparative studies could shed light on the particular strengths of the TEI program in relation to other existing programs, identifying the most effective practices and providing a more comprehensive understanding of how different intervention strategies can influence school dynamics. Additionally, by examining and comparing multiple programs, more robust recommendations for the implementation of education policies focused on promoting a safe, inclusive, and respectful school environment could be derived. This comparative perspective is vital for optimizing interventions and addressing the multifaceted challenges associated with bullying in educational environments.

For a more inclusive vision, future research should focus on the experiences of minority and vulnerable groups, exploring the incidence and consequences of bullying based on factors such as gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or disability.

Despite these insights, this study has limitations. Data were collected through self-report questionnaires, introducing potential response bias. The ex post facto nature of this study limits establishing causality within the results. An experimental design with pre–post measures and control groups could strengthen future studies.

As a prospective direction, implementing a longitudinal study with control and experimental groups is recommended. This would allow for a more rigorous examination of the causal relationships between bullying, social skills, and mental health in TEI schools. Methodological refinements, such as pre–post measures and control groups, would contribute to a nuanced understanding of intervention dynamics over time.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the ongoing importance of preventing bullying, developing social skills, and promoting empathy among ESO students. The TEI program, involving students, teachers, and families, is a step toward creating a safe and healthy school environment, fostering values of respect and mutual support. The goal is to continue working towards an educational setting where each student can realize their full potential.

Author Contributions

V.S. and O.S.-G. have participated in a coordinated manner in the literature review, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results. J.C. and A.M. have supervised and contributed significantly to the elaboration of the conclusions and the final revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, grant numbers UFV2021-09 and UFV2023-52.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Córdoba (protocol code CEIH-21-29 approved on 18 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating schools for their accessibility and contribution to this research. We would also like to thank Universidad Francisco de Vitoria for its professional and financial support, which has been fundamental in reaching the objectives achieved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albaladejo-Blázquez, Natalia, Agustín Caruana-Vañó, Andrés González-Bellido, Pilar Giménez-García, Rosario Ferrer-Cascales, and Miriam Sanchez-SanSegundo. 2016. Assessment of the Peer Tutoring Program (PTP). In Psicología y Educación: Presente y futuro, 1st ed. Edited by Juan Luis Castejón Costa. Madrid: ACIPE-Asociación Científica de Psicología y Educación, vol. 1, pp. 1636–45. ISBN 978-84-608-8714-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaker, Francoise, and Stefan Valkanover. 2012. The Bernese program against victimization in kindergarten and elementary school (Be-Prox). New Directions for Youth Development 133: 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, Pedro Ricardo, and Miriam Catalina González. 2008. Análisis y valoración conceptual sobre las modalidades de tutoría universitaria en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 22: 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Rebecca, and Dion Goh. 2010. Cyberbullying between adolescents: The role of afective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Ciberacoso entre adolescentes: El papel de la empatía afectiva y cognitiva y el género. Psiquiatría Infantil y Desarrollo Humano 41: 387–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armero, Paula, Beatriz Bernardino Cuesta, and Concepción Bonet de Luna. 2011. Acoso escolar. Pediatría Atención Primaria 13: 661–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Armitage, Richard. 2021. Bullying in children: Impact on child health. BMJ Paediatrics Open 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhau, Sujata, and Suninder Tung. 2020. Relationship of Bullying with Affective and Cognitive Empathy among Adolescents. Indian Journal of Psychological Science 12: 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, Rafael, Carlos Colau, Pablo Colau, Jordi Collel, Carme Escudé, Núria Pérez-Escoda, and Rosario Ortega. 2014. Prevención del acoso escolar con educación emocional. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer. [Google Scholar]

- Bochaver, Alexandra. 2021. Consequences of School Bullying for Its Participants. Psychology. Journal of Higher School of Economics 18: 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, Michael, and Kerry Underwood. 1992. Problemas de acosadores/víctimas entre los niños de escuela secundaria. Revista británica de psicología educativa 62: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantera-Espinosa, Leonor, Marisa Vázquez Martínez, and Alicia Pérez Tarrés. 2021. Situación del bullying en España: Leyes, prevención y atención. Olhares: Revista do Departamente de Educação da Unifesp 9: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas-Pardo, Elisabeth. 2017. Acoso escolar: Características, factores de riesgo y consecuencias (Bullying: Characteristics, risk factors and consequences). Revista Doctorado UMH 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Martín, César Cerqueira, Edwin Vereau, and Rosmeri Saucedo. 2017. Habilidades Sociales y Bullying. En Estudiantes De Una Institución Educativa De Chimbote. Colecciones de Investigación Ciencia de la Salud 1: 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Víctor, Rosalba Teyes, and Maigualida Zamora. 2020. Estudio comparativo entre los programas de prevención de la violencia escolar (Comparative Study among Programs for Prevention of School Violence). In Haciendo Ciencia, Construimos Futuro. Edited by Luz Maritza Reyes, Judith Aular de Durán Julio Carruyo, Mónica Chirinos, Sheila Ortega and Dalia Plata. Venezuela: Universidad del Zulla, pp. 580–91. ISBN 978-980-402-302-6. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, Jorge L. D., Wanderlei A. Oliveira, Diene M. Carlos, Elisangela A. Lizzi, Rafaela Rosário, and Marta A. Silva. 2018. Intervenção em habilidades sociais e bullying. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 71: 1085–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Plaza Olivares, Miguel, and Héctor Ordi. 2019. El acoso escolar: Factores de riesgo, protección y consecuencias en víctimas y acosadores. Revista de Victimología 9: 99–131. [Google Scholar]

- Del Rey, Rosario, and Rosario Ortega. 2007. Violencia escolar: Claves para comprenderla y afrontarla. Escuela Abierta: Revista de Investigación Educativa 10: 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dueñas Buey, María Luisa, and María Senra Varela. 2009. Habilidades sociales y acoso escolar: Un estudio en centros de Enseñanza Secundaria de Madrid (Social Skills and school bullying: A study in secondary schools in Madrid). REOP: Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 20: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, Estefanía, Elena Flores, Jesús Estévez, and Elena Huéscar. 2019. Intervention programs in school bullying and cyberbullying in secondary education with effectively evaluated: A systematic review. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 51: 210–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrel, Robert, Andrea Cuan, Zully Londoño, and Lucía Ferrel. 2015. Factores de riesgo y protectores del bullying escolar en estudiantes con bajo rendimiento de cinco instituciones educativas de Santa Marta, Colombia. Psicogente 18: 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Cascales, Rosario, Natalia Albaladejo-Blázquez, Miriam Sánchez-SanSegundo, Irene Portilla-Tamarit, Oriol Lordan, and Nicolás Ruiz-Robledillo. 2019. Eficacia del Programa TEI para la Reducción del Bullying y Cyberbullying y Mejora del Clima Escolar. (Effectiveness of the TEI program for bullying and cyberbullying reduction and school climate improvement). Internacional Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Visús, Andrea, Carmen Casarejos Puente, and Pilar Tormo Irún. 2021. Aspectos neurológicos en la Tutoría Entre Iguales (TEI). In Inteligencia Emocional y Bienestar IV. Reflexiones, Experiencias Profesionales e Investigaciones. Edited by José Luis Soler Nages, José Javier Pedrosa Laplana, Ana Rodríguez Martínez, Alfonso Royo Montané, Rafael Sánchez Sánchez and Verónica Sierra Sánchez. Aragón: Asociación Aragonesa de Psicopedagogía, vol. 1, pp. 338–44. ISBN 978-84-09-32613-6. [Google Scholar]

- González-Bellido, Andrés. 2015. Programa TEI “tutoría entre iguales” (TEI Program “Peer Tutoring”). Innovación Educativa 25: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bellido, Andrés. 2021. Programa TEI: El alumnado como protagonista de la prevención de la violencia y el acoso escolar. Evidencias científicas. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology. INFAD Revista de Psicología 2: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vallejo, Ana Emilse. 2015. Las habilidades sociales en los fenómenos de violencia y acoso escolar. Escuela de Ciencias Sociales, Artes y Humanidades. Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia. Garagoa, Colombia. Repositorio Institucional UNAD. Available online: https://repository.unad.edu.co/handle/10596/3498 (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Hussein, Mohamed. 2013. The social and emotional skills of bullies, victims, and bully–victims of Egyptian primary school children. International Journal of Psychology 48: 910–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, Darrick, and David Farrington. 2006a. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of Adolescence 29: 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, Darrick, and David Farrington. 2006b. Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression 32: 540–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Menestrel, Suzanne. 2020. Preventing Bullying: Consequences, Prevention and Intervention. Journal of Youth Development 15: 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaje, Eva, and Almudena Cotán Fernández. 2020. Acoso escolar en un centro que implementa tutorías entre iguales. Ciencia y Educación 4: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquina Candia, Milagros. 2018. Acoso escolar y habilidades sociales en estudiantes de secundaria de una institución educativa pública del distrito de Cieneguilla. Lima, Perú Facultad de Humanidades, Escuela Académico Profesional de Psicología, Universidad César Vallejo. Lima: Repositorio Digital Institucional. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Criado, José María, and José Antonio Casas. 2019. Evaluación del efecto del Programa de Ayuda entre Iguales de Córdoba sobre el fomento de la Competencia Social y la reducción del Bullying. Aula Abierta 48: 221–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Brenda, and Victoria Maldonado. 2017. Acoso escolar y habilidades sociales en alumnado de educación básica. Ciencia Ergo Sum 24: 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, César, and Mirian Grimaldo-Muchotrigo. 2015. Validación estructural de la Escala Básica de Empatía (Basic Empathy Scale) modificada en adolescentes: Un estudio preliminar. Revista Colombiana de Psicología 24: 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Bataller, Cecilia Beatriz, María Emilia Segatore-Pittón, and Ángel-Javier Tabullo-Tomás. 2019. Empatía, conducta prosocial y “bullying”. Las acciones de los alumnos espectadores. Estudios sobre Educación 37: 113–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Albiol, Luis. 2014. La empatía: Entenderla para entender a los demás. Barcelona: Plataforma Editorial, p. 143. ISBN 978-84-17376-25-3. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva-Delgado, Alfredo, Lucía Antolín-Suárez, Miguel Ángel Pertegal-Vega, Moisés Ríos-Bermúdez, Águeda Parra-Jiménez, Ángel Hernando-Gómez, and Mª Del Carmen Reina-Flores. 2011. Instrumentos para la evaluación de la salud mental y el desarrollo positivo adolescente y los activos que lo promueven. Andalusia: Junta de Andalucía. ISBN 978-84-694-4377-4. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, Dan. 1993. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, p. 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Moore, Mona, and Stephen James Minton. 2004. Dealing with Bullying in Schools: A Training Manual for Teachers, Parents and Other Professionals. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, Rosario. 1997. El proyecto Sevilla Anti-violencia Escolar. Un modelo de intervención preventiva contra los malos tratos entre iguales. Revista de Educación 313: 143–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, Rosario, Rosario Del Rey, and José Antonio Casas. 2016. Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q (Assessing bullying and cyberbullying: Spanish validation of EBIPQ and ECIPQ). Psicología Educativa 22: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Coronel, Andrés Alexis, Pedro Martínez, Javier Bernardo Cabrera, Pablo Andrés Buestán, Esteban Torracchi-Carrasco, and María Gabriela Carpio. 2020. Habilidades sociales y agresividad en la infancia y adolescencia. Archivos venezolanos de farmacología y terapéutica 39: 209–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Antonio, Anabel Pincay, Ana María Payán, Mauricio Herrera-López, and Rosario Ortega-Ruiz. 2021. Los Predictores Psicosociales del Bullying Discriminatorio Debido al Estigma Ligado a las Necesidades Educativas Especiales (NEE) y la Discapacidad. Psicología Educativa. Revista de los Psicólogos de la Educación 27: 187–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, Vanesa, and Beatriz Martín-Moya. 2023. The importance of prevention programs to reduce bullying: A comparative study. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1066358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainz, Vanesa, O’Hara Soto-García, Juan Calmaestra, and Antonio Maldonado. 2023. Impact of the TEI Peer Tutoring Program on Coexistence, Bullying and Cyberbullying in Spanish Schools. Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salavera, Carlos, Pablo Usán, Pilar Teruel, Eva Urbón, and Víctor Murillo. 2021. School bullying: Empathy among perpetrators and victims. Sustainability 13: 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, Christina, Antti Kärnä, and Elisa Poskiparta. 2011. Counteracting Bullying in Finland: The KiVa Program and Its Effects on Different Forms of Being Bullied. International Journal of Behavioral Development 35: 405–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-García, O’Hara, and Vanesa Sainz. 2023. El Programa TEI (Tutoría entre Iguales) para la prevención del acoso escolar y su influencia en la autoestima y la autoeficacia del alumnado de secundaria. In La innovación en el ámbito socioeducativo a través de las tecnologías y la atención a la diversidad, 1st ed. Edited by Alba Vico Bosh and Luisa Vega Caro. Madrid: Dykinson S. L., pp. 724–42. ISBN 978-84-1122-822-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, Mariana L., María M. Peixoto, and Sara Cruz. 2023. The association of social skills and behaviour problems with bullying engagement in Portuguese adolescents: From aggression to victimization behaviors. Current Psychology 42: 11936–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, Cristian, and Ioana Galea. 2014. The development of social and emotional skills of student’s ways to reduce the frequency of bullying-type events. Experimental results. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 114: 735–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinides, Panayiotis, Stelios Georgiou, and Vaso Theofanous. 2010. Bullying and empathy: A short-term longitudinal investigation. Educational Psychology 30: 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, Robert, and Tomas Jungert. 2013. Comportamiento del espectador en situaciones de acoso: Sensibilidad moral básica, desconexión moral y autoeficacia del defensor. Diario de la adolescencia 36: 475–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortosa-Jiménez, Alba. 2018. El aprendizaje de habilidades sociales en el aula. Revista Internacional de apoyo a la Inclusión, Logopedia, Sociedad y Multiculturalidad 4: 158–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttofi, María, and David Farrington. 2012. Bullying prevention programs: The importance of peer intervention, disciplinary methods and age variations. Journal of Experimental Criminology 8: 443–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, Kurniawan Dwi Madyo. 2022. Investigations of Cyber Bullying and Traditional Bullying in Adolescents on the Roles of Cognitive Empathy, Affective Empathy, and Age. International Journal of Instruction 15: 937–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noorden, Tirza H., Antonius H. Cillessen, Gerbert J. Haselager, Tessa A. Lansu, and William M. Bukowski. 2017. Bullying involvement and empathy: Child and target characteristics. Social Development 26: 248–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noorden, Tirza H., Gerbert J. Haselager, Antonius H. Cillessen, and William M. Bukowski. 2015. Empathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44: 637–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadangos Fernández, José M., José M. Errasti Pérez, Isaac Amigo Vázquez, Darrick Jolliffe, and Eduardo García Cueto. 2016. Characteristics of Empathy is Young people measured by Spanish validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Psicothema 28: 323–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).