Adversarial Growth among Refugees: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Who and What Is a Refugee?

1.2. Experiences of Adversity and Consequences for Health

1.3. Central Concepts and Theories of Adversarial Growth

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

- -

- Which factors or circumstances co-occur with adversarial growth?

- -

- How are experiences and expressions of adversarial growth described in the reviewed qualitative literature?

- -

- What is still poorly understood or understudied?

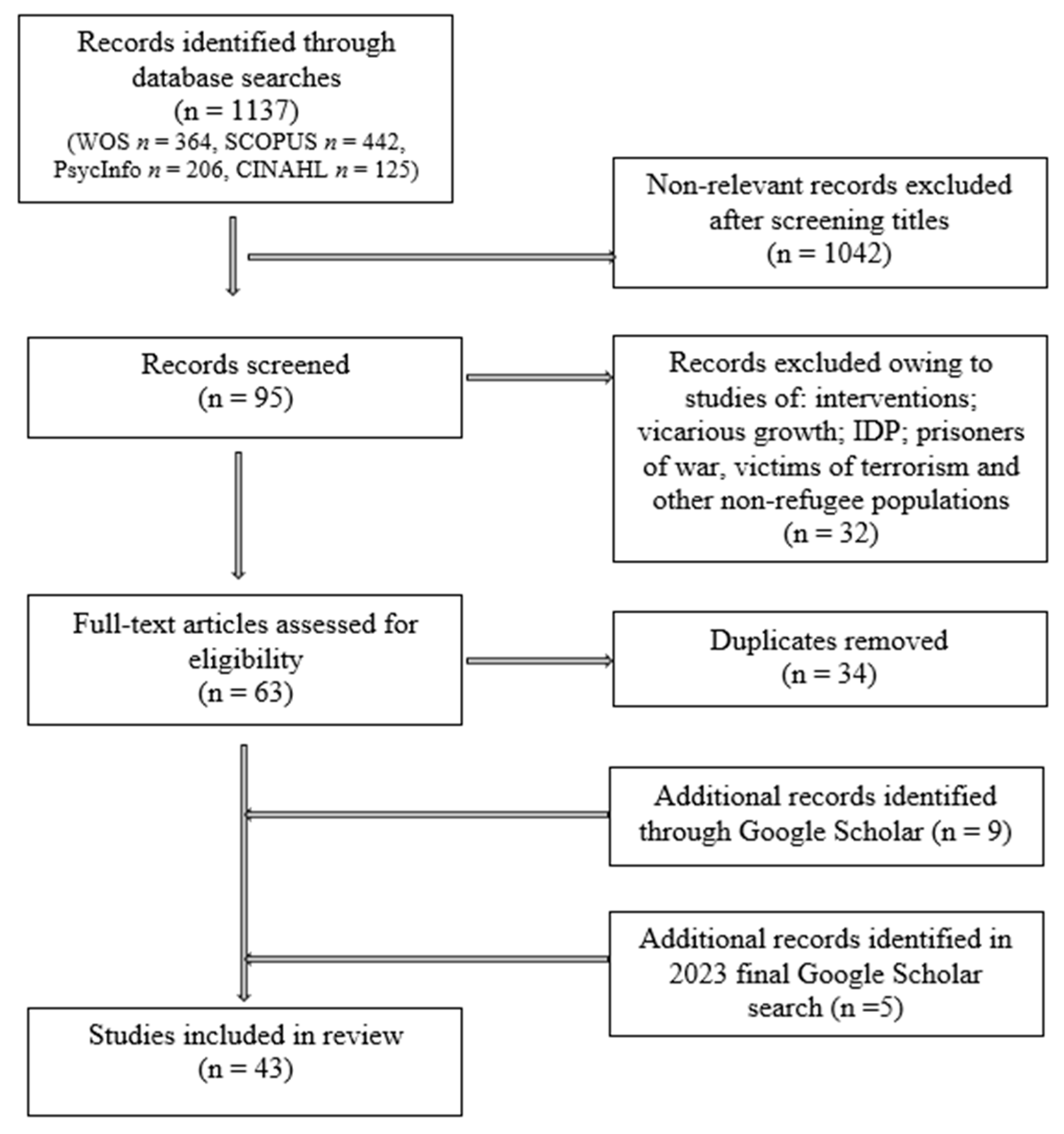

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Growth in Relation to Post-traumatic Stress, Trauma Load, and Sociodemographic Variables

3.1.1. Post-Traumatic Stress and Adversarial Growth

- 8 studies: high or relatively high PTGI scores (range 64.96–84.49)

- 5 studies: moderate PTGI scores (range 49.11–62.54)

- 2 studies: low PTGI scores (range 44.10–47.4)

3.1.2. Number and Characteristics of Adversity

3.1.3. Sociodemographic Correlates

3.2. Individual Factors Related to Growth

3.2.1. Optimism and Positive (Re)Appraisal

3.2.2. Agency, Hope, and Future Orientation

3.2.3. Cognitive Coping Styles

3.2.4. Coping by Doing and Consciously Avoiding

3.3. Social, Religious, and Cultural Variables and Aspects of Growth

3.3.1. Social Support and Sharing

3.3.2. Religiosity and Spirituality as a Source of Strength

3.3.3. Growth Nourished by Culture and Worldviews

3.4. Personal Experiences and Manifestations of Growth

3.4.1. Self-Image as Survivor with Newfound Strength and Wisdom

3.4.2. Changes in Life Priorities—Perspectives, Purpose, and Meaning

3.4.3. Compassion, Empathy, and Pro-Social Engagement

3.4.4. Resilience, Health, and Wellbeing

3.5. Growth and the Interplay of Time, Place, and Post-Migration Factors

3.5.1. The Passing of Time

3.5.2. Post-Migration Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Mediated Images of Refugees

4.2. The Dynamic and Interactional Nature of Growth

4.3. The Subjective Experience of Adversarial Growth

4.4. Time and Post-Migration Stressors

4.5. Culture, Worldviews, Spirituality, and Meaning

4.6. Cross-Cultural Applicability of the Five-Factor Model of Post-traumatic Growth (PTG)?

4.7. Areas for Future Exploration: Unanswered Questions

5. Concluding Remarks and Key Practical Implications

Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Quantitative and Mixed-Methods Studies (n = 23). | |||

| Author (Year) | Study and Sample Characteristics | Outcome Measures | Key Findings |

| Acquaye (2017) |

|

|

|

| Acquaye et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

| Ai et al. (2007) |

|

|

|

| Canevello et al. (2022) |

|

|

|

| Cengiz et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

| Ersahin (2020) |

|

|

|

| Hussain and Bhushan (2011) |

|

|

|

| Kira et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

| Kopecki (2010) |

|

|

|

| Kroo and Nagy (2011) |

|

|

|

| Maier et al. (2022) |

|

|

|

| Mwanamwambwa (2023) |

|

|

|

| Ochu et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

| Powell et al. (2003) |

|

|

|

| Rizkalla and Segal (2018) |

|

|

|

| Rosner and Powell (2006) |

|

|

|

| Şimşir et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

| Sleijpen et al. (2016) |

|

|

|

| Ssenyonga et al. (2013) |

|

|

|

| Taher and Allan (2020) |

|

|

|

| Tekie (2018) |

|

|

|

| Teodorescu et al. (2012) |

|

|

|

| Umer and Elliot (2019) |

|

|

|

| Qualitative Studies (n = 20). | |||

| Author (Year) | Study and Sample Characteristics | Key Findings | |

| Abraham et al. (2018) |

|

| |

| Copelj et al. (2017) |

|

| |

| Copping et al. (2010) |

|

| |

| Ferriss and Forrest-Bank (2018) |

|

| |

| Gilpin-Jackson (2012) |

|

| |

| Hirad et al. (2023) |

|

| |

| Hirad (2018) |

|

| |

| Dilwar Hussain and Bhushan (2013) |

|

| |

| Kim and Lee (2009) |

|

| |

| Maung (2018) |

|

| |

| McCormack and Tapp (2019) |

|

| |

| Prag and Vogel (2013) |

|

| |

| Sesay (2015) |

|

| |

| Shakespeare-Finch et al. (2014) |

|

| |

| Şimşir et al. (2018) |

|

| |

| Sutton et al. (2006) |

|

| |

| Taylor et al. (2020) |

|

| |

| Uy and Okubo (2018) |

|

| |

| Wehrle et al. (2018) |

|

| |

References

- Abraham, Ruth, Lars Lien, and Ingrid Hanssen. 2018. Coping, resilience and post-traumatic growth among Eritrean female refugees living in Norwegian asylum reception centres: A qualitative study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 64: 359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaye, Hannah E. 2017. PTSD, Optimism, Religious Commitment, and Growth as Post-Trauma Trajectories: A Structural Equation Modeling of Former Refugees. Professional Counselor 7.4: 330–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaye, Hannah E., Stephen A. Sivo, and K. Dayle Jones. 2018. Religious Commitment’s Moderating Effect on Refugee Trauma and Growth [Article]. Counseling and Values 63: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affleck, Glenn, and Howard Tennen. 1996. Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptotional significance and disposltional underpinnings. Journal of Personality 64: 899–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., Terrence N. Tice, Donna D. Whitsett, Tony Ishisaka, and Metoo Chim. 2007. Post-traumatic symptoms and growth of Kosovar war refugees: The influence of hope and cognitive coping. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Yasmin. 2023. Xenophobia and Hate Speech towards Refugees on Social Media: Reinforcing Causes, Negative Effects, Defense and Response Mechanisms against That Speech. Societies 13: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Krenawi, Alean, Salman Elbedour, Janice E. Parsons, Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie, William M. Bart, and Angela Ferguson. 2011. Trauma and war: Positive psychology/strengths approach. Arab Journal of Psychiatry 23: 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. 2022. Poland: Cruelty, Not Compassion, at Europe’s Other Borders (Amnesty International Public Statement). Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur37/5460/2022/en/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Antonovsky, Aaron. 1987. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, and Laura L. Shaw. 1991. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry 2: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Roni, and Tzipi Weiss. 2003. Immigration and Post-traumatic Growth—A Missing Link. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Services 1: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, George A. 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist 59: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, George A., Dacher Keltner, Are Holen, and Mardi J. Horowitz. 1995. When avoiding unpleasant emotions might not be such a bad thing: Verbal-autonomic response dissociation and midlife conjugal bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 975–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bø, Bente Puntervold, and Asla Maria Bø Fuglestad. 2022. Velferdsstatens Skyggeside—Rettighetstap for Minoriteter [The Shadow Side of the Welfare State—Loss of Rights for Minorities]. Seoul: Mira. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Volume 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kate, Kathryn Ecclestone, and Nick Emmel. 2017. The many faces of vulnerability. Social Policy and Society 16: 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevello, Amy, Jonathan Hall, and James Igoe Walsh. 2022. Empathy-mediated altruism in intergroup contexts: The roles of post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth. Emotion 22: 1699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, Arnie, Lawrence G. Calhoun, Richard G. Tedeschi, Kanako Taku, Tanya Vishnevsky, Kelli N. Triplett, and Suzanne C. Danhauer. 2010. A short form of the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 23: 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz, Ibrahim, Deniz Ergun, and Ebru Çakıcı. 2019. Post-traumatic stress disorder, post-traumatic growth and psychological resilience in Syrian refugees: Hatay, Turkey. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry 20: 269–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. Jacky, Marta Y. Young, and Noor Sharif. 2016. Well-being after trauma: A review of post-traumatic growth among refugees. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 57: 291–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Karmel W., Murray B. Stein, Erin C. Dunn, Karestan C. Koenen, and Jordan W. Smoller. 2019. Genomics and psychological resilience: A research agenda. Molecular Psychiatry 24: 1770–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copelj, Anja, Peter Gill, Anthony W. Love, and Susan J. Crebbin. 2017. Psychological growth in young adult refugees: Integration of personal and cultural resources to promote wellbeing. Australian Community Psychologist 28: 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Copping, Alicia, Jane Shakespeare-Finch, and Douglas Paton. 2010. Towards a Culturally Appropriate Mental Health System: Sudanese-Australians’ Experiences with Trauma. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 4: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersahin, Zehra. 2020. Post-traumatic growth among Syrian refugees in Turkey: The role of coping strategies and religiosity. Current Psychology 41: 2398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esses, Victoria M., Stelian Medianu, and Andrea S. Lawson. 2013. Uncertainty, threat, and the role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. Journal of Social Issues 69: 518–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Amanda M., Annette Kluck, Doris Hill, Eric Crumley, and Joshua Turchan. 2017. Utilizing existential meaning-making as a therapeutic tool for clients affected by poverty. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy 6: 16. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, Mina, Jeremy Wheeler, and John Danesh. 2005. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet 365: 1309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferriss, Sarah Strode, and Shandra S. Forrest-Bank. 2018. Perspectives of Somali Refugees on Post-traumatic Growth after Resettlement. Journal of Refugee Studies 31: 626–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiankan-Bokonga, Catherine. 2022. Norwegian Refugee Council chief: Attention on Ukraine war reveals ‘discrimination’ against African crises. Peace & Humanitarian Refugees News. Available online: https://genevasolutions.news/peace-humanitarian/norwegian-refugee-council-chief-attention-on-ukraine-war-reveals-discrimination-against-african-crises (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Frankl, Viktor Emil. 1963. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logetheraphy. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franquet Dos Santos Silva, Miguel, Svein Brurås, and Ana Beriain Bañares. 2018. Improper Distance: The Refugee Crisis Presented by Two Newsrooms. Journal of Refugee Studies 31: 507–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Patricia, Christiaan Greer, Susanne Gabrielsen, Howard Tennen, Crystal Park, and Patricia Tomich. 2013. The relation between trauma exposure and prosocial behavior. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 5: 286–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin-Jackson, Yabome. 2012. “Becoming Gold”: Understanding the Post-War Narratives of Transformation of African Immigrants and Refugees. Santa Barbara: Fielding Graduate University. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Janice H. 2004. Coping with trauma and hardship among unaccompanied refugee youths from Sudan. Qualitative Health Research 14: 1177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschald, Gabriela M., and Susan Sierau. 2020. Growing Up in Times of War: Unaccompanied Refugee Minors’ Assumptions About the World and Themselves. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 18: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 26: 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, David M., Simon Baron-Cohen, Nora Rosenberg, Peter Fonagy, and Peter J. Rentfrow. 2018. Elevated empathy in adults following childhood trauma. PLoS ONE 13: e0203886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgeson, Vicki S., Kerry A. Reynolds, and Patricia L. Tomich. 2006. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74: 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Judith L. 1998. Recovery from psychological trauma. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 52: 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirad, Sara. 2018. The Process through which Middle Eastern Refugees Experience Post-traumatic Growth. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 78, No Pagination Specified. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=psyc15&AN=2017-29362-055 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Hirad, Sara, Marianne McInnes Miller, Sesen Negash, and Jessica E. Lambert. 2023. Refugee post-traumatic growth: A grounded theory study. Transcultural Psychiatry 60: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Brian J. Hall, Daphna Canetti-Nisim, Sandro Galea, Robert J. Johnson, and Patrick A. Palmieri. 2007. Refining our understanding of traumatic growth in the face of terrorism: Moving from meaning cognitions to doing what is meaningful. Applied Psychology 56: 345–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthe, Mira Elise Glaser. 2023. When Giving Up Is Not an Option, Out of Suffering Have Emerged the Strongest Souls: Coping, Meaning Making, and Adversarial Growth among Young Adults with Refugee Backgrounds. Ph.D. Thesis, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Lillehammer, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Dilwar, and Braj Bhushan. 2011. Post-traumatic stress and growth among Tibetan refugees: The mediating role of cognitive-emotional regulation strategies. Journal of Clinical Psychology 67: 720–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, Dilwar, and Braj Bhushan. 2013. Post-traumatic Growth Experiences among Tibetan Refugees: A Qualitative Investigation. Qualitative Research in Psychology 10: 204–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, Rick E., and C. R. Snyder. 2006. Blending the good with the bad: Integrating positive psychology and cognitive psychotherapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy 20: 117–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, Helia, Anusha Kassan, Gudrun Reay, and Emma A. Climie. 2022. Resilience in refugee children and youth: A critical literature review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 63: 678–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickreme, Eranda, Nuwan Jayawickreme, Corinne E. Zachry, and Michelle A. Goonasekera. 2019. The importance of positive need fulfillment: Evidence from a sample of war-affected Sri Lankans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 89: 159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Stephen, and P. Alex Linley. 2005. Positive Adjustment to Threatening Events: An Organismic Valuing Theory of Growth Through Adversity. Review of General Psychology 9: 262–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Stephen, and P. Alex Linley. 2006. Growth following adversity: Theoretical perspectives and implications for clinical practice. Clinical Psychology Review 26: 1041–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, Boaz, Eva Kahana, Zev Harel, and Mary Segal. 1986. The Victim as Helper-Prosocial Behavior during the Holocaust. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 13: 357–73. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, Serap, Oddgeir Friborg, Thormod Idsøe, Selcuk Sirin, and Brit Oppedal. 2016. Depression among unaccompanied minor refugees: The relative contribution of general and acculturation-specific daily hassles. Ethnicity & Health 21: 300–17. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, Dacher, Aleksandr Kogan, Paul K. Piff, and Sarina R. Saturn. 2014. The sociocultural appraisals, values, and emotions (SAVE) framework of prosociality: Core processes from gene to meme. Annual Review of Psychology 65: 425–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khursheed, Masrat, and Mohammad Ghazi Shahnawaz. 2020. Trauma and Post-traumatic Growth: Spirituality and Self-compassion as Mediators among Parents Who Lost Their Young Children in a Protracted Conflict. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2623–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyun Kyoung, and Ok Ja Lee. 2009. A Phenomenological Study on the Experience of North Korean Refugees. Nursing Science Quarterly 22: 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, Ibrahim Aref, Hanaa Shuwiekh, Boshra Al Ibraheem, and Jakoub Aljakoub. 2018. Appraisals and emotion regulation mediate the effects of identity salience and cumulative stressors and traumas, on PTG and mental health: The case of Syrian’s IDPs and refugees. Self and Identity 18: 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleim, Birgit, and Anke Ehlers. 2009. Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between post-traumatic growth and posttrauma depression and PTSD in assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 22: 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, Hans Henri P., Zsuzsanna Jakab, Jozef Bartovic, Veronika D’Anna, and Santino Severoni. 2020. Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet 395: 1237–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, Ravi K. S., Marte Knag Fylkesnes, Mervi Kaukko, and Sarah C. White. 2023. Special Issue “Wellbeing in the Lives of Young Refugees”. Call for Papers. Social Sciences. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci/special_issues/OTN5832Z04 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Kopecki, Vedrana. 2010. Post-traumatic Growth in Refugees: The Role of Shame and Guilt-Proneness, World Assumptions and Coping Strategies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ballarat, Ballarat, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Kroo, Adrienn, and Henriett Nagy. 2011. Post-traumatic Growth among Traumatized Somali Refugees in Hungary. Journal of Loss and Trauma 16: 440–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, Cornelis J., Hajo B. P. E. Gernaat, Ivan H. Komproe, Bettine A. Schreuders, and Joop T. V. M. De Jong. 2004. Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in The Netherlands. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192: 843–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifton, Robert J. 1980. The concept of the survivor. In Survivors, Victims, and Perpetrators: Essays on the Nazi Holocaust. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, pp. 113–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Daniel, and David DeSteno. 2016. Suffering and compassion: The links among adverse life experiences, empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. Emotion 16: 175–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linley, P. Alex, and Stephen Joseph. 2004. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress 17: 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maercker, Andreas, and Tanja Zoellner. 2004. The Janus face of self-perceived growth: Toward a two-component model of post-traumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry 15: 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Kathrin, Karol Konaszewski, Sebastian Binyamin Skalski, Arndt Büssing, and Janusz Surzykiewicz. 2022. Spiritual Needs, Religious Coping and Mental Wellbeing: A Cross-Sectional Study among Migrants and Refugees in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkki, Liisa H. 1996. Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization. Cultural Anthropology 11: 377–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E. Anne, Kathryn Butler, Tricia Roche, Jessica Cumming, and Joelle T. Taknint. 2016. Refugee Youth: A Review of Mental Health Counselling Issues and Practices. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne 57: 308–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, Stephan, Ina Giegling, Chiara Fabbri, Filippo Corponi, Alessandro Serretti, and Dan Rujescu. 2020. Genetics of resilience: Implications from genome-wide association studies and candidate genes of the stress response system in post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. American Journal of Medical Genetics 183: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maung, Joanna Chee. 2018. Burmese Refugee Women in Resettlement: Narratives of Strength, Resilience, and Post-traumatic Growth. Kansas City: University of Missouri—Kansas City. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, Lynne, and Brigitta Tapp. 2019. Violation and hope: Refugee survival in childhood and beyond. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 65: 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Kenneth E., and Andrew Rasmussen. 2010. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine 70: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, Edith. 2011. Trauma, exile and mental health in young refugees. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 124: 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwanamwambwa, Victor. 2023. The Relationship between Religion, Spirituality and Mental Health in Rwandan Refugees: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 7: 111–21. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:bcp:journl:v:7:y:2023:i:2:p:111-121 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Ní Raghallaigh, Muireann. 2010. Religion in the lives of unaccompanied minors: An available and compelling coping resource. British Journal of Social Work 41: 539–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth. 1993. The Spiral of Silence: Public Opinion—Our Social Skin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nutting, Tom. 2019. Headaches in Moria: A reflection on mental healthcare in the refugee camp population of Lesbos. BJPsych International 16: 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochu, Austin C., Edward B. Davis, Gina Magyar-Russell, Kari A. O’Grady, and Jamie D. Aten. 2018. Religious coping, dispositional forgiveness, and post-traumatic outcomes in adult survivors of the Liberian Civil War. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 5: 104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeri, Akram, Christopher Lennings, and Lyn Raymond. 2004. Hardiness and transformational coping in asylum seekers: The Afghan experience. Diversity in Health & Social Care 1: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, Renos K. 2007. Refugees, trauma and adversity-activated development. European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling 9: 301–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2005. Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues 61: 707–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L., Lawrence H. Cohen, and Renee L. Murch. 1996. Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality 64: 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Jessica, Patricia F. Pearce, Laurie Anne Ferguson, and Cynthia A. Langford. 2017. Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners 29: 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piguet, Etienne. 2020. The ‘refugee crisis’ in Europe: Shortening distances, containment and asymmetry of rights—A tentative interpretation of the 2015–16 events. Journal of Refugee Studies 34: 1577–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Matthew, and Nick Haslam. 2005. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA 294: 602–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, Steve, Rita Rosner, Willi Butollo, Richard G. Tedeschi, and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 2003. Post-traumatic growth after war: A study with former refugees and displaced people in Sarajevo. Journal of Clinical Psychology 59: 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prag, Hillary, and Gwen Vogel. 2013. Therapeutic photography: Fostering posttraumatic growth in Shan adolescent refugees in northern Thailand. Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas 11: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, Leigh, and Lee Martin. 2018. Introduction to the special issue: Applied critical realism in the social sciences. Journal of Critical Realism 17: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupavac, Vanessa. 2006. Refugees in the ‘Sick Role’: Stereotyping Refugees and Eroding Refugee Rights. Geneva: UNHCR, Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla, Niveen, and Steven P. Segal. 2018. Well-Being and Post-traumatic Growth among Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Journal of Traumatic Stress 31: 213–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, Rita, and Steve Powell Powell. 2006. Post-traumatic growth after war. In Handbook of Post-traumatic Growth: Research and Practice. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, Michael. 1987. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 57: 316–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwanpura, Eshani, Stewart W. Mercer, Alastair Ager, and Gerard Duveen. 2006. Cultural and spiritual constructions of mental distress and associated coping mechanisms of Tibetans in exile: Implications for Western interventions. Journal of Refugee Studies 19: 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saleebey, Dennis. 2002. The Strengths Perspective in Social Work Practice. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Sesay, Margaret Konima. 2015. Contributing Factors to the Development of Positive Responses to the Adversity Endured by Sierra Leonean Refugee Women Living in the United Kingdom. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Essex, Colchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch, Jane, and Janine Lurie-Beck. 2014. A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between post-traumatic growth and symptoms of post-traumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 28: 223–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare-Finch, Jane, Robert D. Schweitzer, Julie King, and Mark Brough. 2014. Distress, Coping, and Post-traumatic Growth in Refugees from Burma. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 12: 311–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, Derrick, Ingrid Sinnerbrink, Annette Field, Vijaya Manicavasagar, and Zachary Steel. 1997. Anxiety, depression and PTSD in asylum-seekers: Assocations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stressors. The British Journal of Psychiatry 170: 351–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, Katrina, and Julie Ann Pooley. 2017. Post-traumatic growth amongst refugee populations: A systematic review. In The Routledge International Handbook of Psychosocial Resilience. Edited by U. Kumar. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 230–47. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşir Gökalp, Zeynep, and Abdulkadir Haktanir. 2022. Post-traumatic growth experiences of refugees: A metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Journal of Community Psychology 50: 1395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şimşir, Zeynep, Bülent Dilmaç, and Hatice İrem Özteke Kozan. 2018. Post-traumatic Growth Experiences of Syrian Refugees after War. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 61: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleijpen, Marieke, Joris Haagen, Trudy Mooren, and Rolf J. Kleber. 2016. Growing from experience: An exploratory study of post-traumatic growth in adolescent refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 7: 28698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleijpen, Marieke, Trudy Mooren, Rolf J. Kleber, and Hennie R. Boeije. 2017. Lives on hold: A qualitative study of young refugees’ resilience strategies. Childhood 24: 348–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, Charles R., and Shane J. Lopez. 2001. Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ssenyonga, Joseph, Vicki Owens, and David Kani Olema. 2013. Post-traumatic Growth, Resilience, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among Refugees. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 82: 144–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, Ervin, and Johanna Vollhardt. 2008. Altruism born of suffering: The roots of caring and helping after victimization and other trauma. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 78: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellar, Jennifer E., Amie M. Gordon, Paul K. Piff, Daniel Cordaro, Craig L. Anderson, Yang Bai, Laura A. Maruskin, and Dacher Keltner. 2017. Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review 9: 200–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultani, Grace, Milena Heinsch, Jessica Wilson, Phillip Pallas, Campbell Tickner, and Frances Kay-Lambkin. 2024. ‘Now I Have Dreams in Place of the Nightmares’: An Updated Systematic Review of Post-Traumatic Growth among Refugee Populations. Trauma, Violence & Abuse 25: 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Vicky, Ian Robbins, Vicky Senior, and Sedwick Gordon. 2006. A qualitative study exploring refugee minors personal accounts of post-traumatic growth and positive change processes in adapting to life in the UK. Diversity & Equality in Health and Care 3: 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanik, Marta. 2016. The ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ Refugees? Imagined Refugeehood(s) in the Media Coverage of the Migration Crisis. Journal of Identity and Migration Studies 10: 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Taher, Rayan, and Thérèse Allan. 2020. Posttraumatic growth in displaced Syrians in the UK: A mixedmethods approach. Journal of Loss and Trauma 25: 333–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steve, Divine Charura, Glenn Williams, Mandy Shaw, John Allan, Elliot Cohen, Fiona Meth, and Leonie O’Dwyer. 2020. Loss, Grief and Growth: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Experiences of Trauma in Asylum-Seekers and Refugees. Traumatology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 1995. Trauma and Transformation. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 1996. The Post-traumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9: 455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 2004. Post-traumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry 15: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., Arnie Cann, Kanako Taku, Emre Senol-Durak, and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 2017. The post-traumatic growth inventory: A revision integrating existential and spiritual change. Journal of Traumatic Stress 30: 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekie, Yacob Tewolde. 2018. The Role of Meaning-Making in Post-traumatic Growth among Eritrean Refugees with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, YN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, Dinu-Stefan, Johan Siqveland, Trond Heir, Edvard Hauff, Tore Wentzel-Larsen, and Lars Lien. 2012. Post-traumatic growth, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress symptoms, post-migration stressors and quality of life in multi-traumatized psychiatric outpatients with a refugee background in Norway. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 10: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, Madeha, and Dely Lazarte Elliot. 2019. Being Hopeful: Exploring the Dynamics of Post-traumatic Growth and Hope in Refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies 34: 953–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. 2008. Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work 38: 218–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2023. Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2022. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2022 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Updegraff, John A., and Shelley E. Taylor. 2000. From vulnerability to growth: Positive and negative effects of stressful life events. Loss and Trauma: General and Close Relationship Perspectives 25: 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Uy, K. Kara, and Yuki Okubo. 2018. Reassembling a shattered life: A study of post-traumatic growth in displaced Cambodian community leaders. Asian American Journal of Psychology 9: 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Arcosy, Cheyenne, Mariana Padilha, Gabriel Lorran Mello, Liliane Vilete, Mariana Pires Luz, Mauro Mendlowicz, Octavio Domont Serpa, and William Berger. 2023. A bright side of adversity? A systematic review on post-traumatic growth among refugees. Stress and Health 39: 956–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrle, Katja, Ute-Christine Klehe, Mari Kira, and Jelena Zikic. 2018. Can I come as I am? Refugees’ vocational identity threats, coping, and growth. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Tzipi, and Roni Berger. 2010. Post-Traumatic Growth and Culturally Competent Practice: Lessons Learned from Around the Globe. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Karen, Michael McGrath, Ceren Acarturk, Zeynep Ilkkursun, Daniela C. Fuhr, Egbert Sondorp, Bayard Roberts, and Marit Sijbrandij. 2020. Post-traumatic growth and its predictors among Syrian refugees in istanbul: A mental health population survey. Journal of Migration and Health 1: 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, Lori, Belinda Graham, Elizabeth Marks, Norah Feeny, Jacob Bentley, Anna Franklin, and Duniya Lang. 2018. Islamic Trauma Healing: Initial Feasibility and Pilot Data. Societies 8: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 3.1. Prevalence of Growth in Relation to PTS, Trauma Load, and Sociodemographic Variables |

| 3.1.1. Post-traumatic Stress and Adversarial Growth |

| 3.1.2. Number and Characteristics of Adversity |

| 3.1.3. Sociodemographic Correlates |

| 3.2. Individual Factors Related to Growth |

| 3.2.1. Optimism and Positive (Re)Appraisal |

| 3.2.2. Agency, Hope and Future Orientation |

| 3.2.3. Cognitive Coping Styles |

| 3.2.4. Coping by Doing and Consciously Avoiding |

| 3.3. Social, Religious, and Cultural Variables and Aspects of Growth |

| 3.3.1. Social Support and Sharing |

| 3.3.2. Religiosity and Spirituality as a Source of Strength |

| 3.3.3. Growth Nourished by Culture and Worldviews |

| 3.4. Personal Experiences and Manifestations of Growth |

| 3.4.1. Self-Image as Survivor with Newfound Strength and Wisdom |

| 3.4.2. Changes in Life Priorities—Perspectives, Purpose, and Meaning |

| 3.4.3. Compassion, Empathy, and Pro-Social Engagement |

| 3.4.4. Growth, Mental Health, and Wellbeing |

| 3.5. The Interplay of Time, Place, and Post-Migration Factors |

| 3.5.1. The Passing of Time |

| 3.5.2. Post-Migration Factors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holthe, M.E.G.; Söderström, K. Adversarial Growth among Refugees: A Scoping Review. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010046

Holthe MEG, Söderström K. Adversarial Growth among Refugees: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolthe, Mira Elise Glaser, and Kerstin Söderström. 2024. "Adversarial Growth among Refugees: A Scoping Review" Social Sciences 13, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010046

APA StyleHolthe, M. E. G., & Söderström, K. (2024). Adversarial Growth among Refugees: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences, 13(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010046