Abstract

This article studies the differences in the correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share for different Hispanic subgroups in New York City. Such differences are predicted by Segmented Assimilation Theory as different assimilation paths. The study is carried out at the level of PUMAs, and it is argued that such geographic locations are macro-level factors that determine health outcomes, as the theory of Racialized Place Inequality Framework claims. The study presents a spatially correlated model that allows to decompose the spatial effects into direct and indirect effects. Direct effects are linked to the macro structure where the individual lives, while indirect effects refer to effects in the adjacent macro structures where the individual lives. The results show that both types of effects are significant. The importance of the direct effects is predicted by RPIF, while the importance of the indirect effects is a new result that shows the complexity of the effects of macro structures. The article also shows results for subsamples that allow to test the importance of different factors that have been linked to the excess deaths observed among Hispanics. The effects of such factors are also found to be heterogenous among the different Hispanic subgroups, which also provides evidence in favor of the Segmented Assimilation Theory. Access to health insurance and doctor density are found to be the most important elements that serve as protective factors for all Hispanic subgroups in New York City, signaling its importance in achieving assimilation for Hispanic immigrants to New York City.

1. Introduction

Recent research has documented the existence of a positive correlation between the Hispanic share and the death rate due to COVID-19 in the US population (Andrasfay and Goldman 2021) and in specific US states (Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha 2023; Laurencin et al. 2021; Riley et al. 2021). Specifically, Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha (2023) document that, among Hispanic males living in New York City, such positive correlation persists even when controlling for the characteristics of the geographic area where they live, while, for women, such correlation vanishes after controlling for the characteristics of the geographic area. Finding such positive correlation among Hispanics is, to some extent, surprising, considering that many studies have shown that the first generation of Hispanic immigrants to the US have better health indicators, a result that has been called the Hispanic health paradox. It is called a paradox, because previous research using data at the individual level has shown that individuals with lower socioeconomic characteristics have lower health outcomes, but first-generation Hispanics with low socioeconomic characteristics are healthier (Vega et al. 2009; Ruiz et al. 2013; Dominguez et al. 2015).

The first research question of this paper is to determine if the reported positive correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share is found among different Hispanic subgroups, classified by their place of birth. There exists ample literature that has shown that the Hispanic population of the US is not homogeneous and that there exists heterogeneity in health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups (Albrecht et al. 1996; Acevedo-Garcia et al. 2007; Jerant et al. 2008; Rodriguez et al. 2017; Garcia et al. 2018; Zamora et al. 2019; Garcia et al. 2021a). There are different reasons explaining the heterogeneity of the Hispanic population; one of those refers to the place of birth, since some of the Hispanic subgroups are immigrants born in foreign countries (i.e., individuals born in Mexico), and some are US citizens born in US territories (i.e., Puerto Ricans), while others are US citizens born in the continental US (US citizens of Cuban descent) (Zamora et al. 2019). The different Hispanic subgroups studied are selected because they represent at least 4% of the Hispanic population of New York City. The subgroups selected are US-born Hispanics, Mexicans, Salvadoreans, Dominicans, Central Americans without Salvadoreans, South Americans, and other foreign-born Hispanics. This last group was integrated to capture the rest of the Hispanic population, since it only represents 1.1% of the Hispanic population of New York City.1 According to one immigrant assimilation theory, the existence of such a positive correlation could exist only among recently immigrated individuals, since, over time, immigrants assimilate into US culture (Gordon 1964). For other theories, the positive correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share is explained because Hispanic immigrants may be part of an underclass in the US (Tienda 1989), since they suffer from a deterioration of their socioeconomic characteristics because of their exposure to harsh living conditions. Another theoretical explanation comes from Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993), where it is argued that immigrants face different paths of assimilation; one of which is called the downward mobility, where immigrants fail or refuse to incorporate into the mainstream, which locks them up in economically disadvantaged living conditions.

The second research question of the paper is to identify if there is more than one type of correlation found between deaths and the Hispanic subgroup share, which would be an indication that there is more than one path of assimilation for Hispanic immigrants. According to Segmented Assimilation Theory, besides the downward assimilation path mentioned earlier, there is also a path of assimilation, where immigrants become indistinguishable overt time and generations, and a path of upward assimilation, where immigrants assimilate into ethnic enclaves (Portes and Zhou 1993).

The third research question of the paper is to analyze if there is evidence that macro-level factors, like the one represented by Population Units Metropolitan Areas (PUMAs), influence the health outcomes of the immigrant population. PUMAs are units exogenously chosen by the Census authority of the US, depending on concentrating no fewer than 100,000 and no more than 200,000 individuals. According to Racialized Place Inequality Framework (RPIF) (Burgos et al. 2017; Velez 2017), micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors determine the outcomes of immigrants in the US. Under such a theoretical approach, the individual characteristics of individuals, the characteristics of neighborhoods, and the characteristics of county and metropolitan areas are linked to outcomes observed among the population. This theoretical explanation provides a reason to observe spatial correlations in health outcomes, an aspect that has been noticed in the recent literature (Hochschild 2016; Fuentes-Mayorga and Burgos 2017). In the context of COVID-19, studies have also reported the importance of spatial correlation (Saffary et al. 2020; Zhu et al. 2021; Bossak and Andritsch 2022; Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha 2023). This paper presents a random effect spatially correlated model that allows to estimate the impact of direct effects, linked to the PUMA where individuals live, and indirect effects, linked to the influence of PUMAs adjacent to the one where the individual lives (Kelejian and Prucha 1999). Finding direct and indirect effects of the macro structure helps better define the effects of the macro structures that RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017) claims define the health outcomes of individuals. The fact that PUMAs are exogenously chosen units allows an unbiased estimation of the parameters in the regression analysis presented in this paper (Greene 2000).

The fourth research question analyzes if the different explanations provided in the literature for the existence of the positive correlation eliminate the importance of Segmented Assimilation Theory and RPIF. The paper shows estimations for subsamples where the population is selected to observe the influence of different factors that have been argued as explanations for the positive correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share, like the risk of exposure due to the occupations of the Hispanic population (Riley et al. 2021), the deficient access to health care and vaccination among them (Riley et al. 2021), and the weathering process that the Hispanic population experiences due to continuous exposure to hard living conditions over the medium and long term (Garcia et al. 2021b). The results show evidence in favor of the existence of different assimilation paths (Portes and Zhou 1993) and the importance of macro-level factors (Burgos et al. 2017; Velez 2017). The results also reveal the importance of the access to health insurance to achieve assimilation for the Hispanic population of New York City.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The rest of the first part reviews the literature on the Hispanic health paradox, immigrant assimilation theories, the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Hispanic population, the importance of spatial correlation in understanding the effects of COVID-19, and the literature on the heterogeneous health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups; the second part presents the data and our empirical models to calculate death differentials for the Hispanic subgroups; the third part presents the results from empirical analyses; the fourth part discusses the results; and the fifth part presents the conclusions and policy implications of the paper.

1.1. Theoretical Considerations

1.1.1. The Hispanic Health Paradox

Many studies have shown the existence of a Hispanic health paradox (Vega et al. 2009; Ruiz et al. 2013; Dominguez et al. 2015), which is a reported higher-than-average life expectancy among the first and 1.5 generations of the Hispanic population, despite their vulnerable socioeconomic characteristics and their lower access to health insurance and lower visits to doctors for preventive medical care (Funk and Lopez 2022). For some researchers, this advantage in life expectancy may be due to factors such as diet, lower rates of smoking, and strong family and social support (Dominguez et al. 2015). Moreover, the Hispanic health paradox does not occur for all types of diseases, since Hispanics have higher death rates due to cardiovascular disease (Montanez-Valverde et al. 2021), diabetes, chronic liver disease, and homicide, as well as a higher rate of obesity than Whites (Dominguez et al. 2015). Other studies have also reported that, for certain diseases like heart failure, the mortality rate of the Hispanic population has converged in recent years towards the non-Hispanic White population (Kahn et al. 2022). Recent research has shown that the Hispanic health paradox is also found in lung cancer survival rates (Price et al. 2021). These latter results have been related to differences in cultural values that lead to higher social connections that may have health related benefits (Ruiz et al. 2016).

1.1.2. Immigrant Assimilation Theories

Gordon (1964) argued that immigrants in the US experienced a gradual process of assimilation to the host country. This assimilation takes place in the following seven variables: cultural, structural, marital, self-identification, attitudinal and behavioral, and civic. Some authors (Tienda 1989) argued that certain groups of immigrants may fail to assimilate and become a social underclass, because they may suffer a deterioration in their socioeconomic characteristics due to their continuous exposure to harsh living conditions. According to Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993), there are three different pathways that immigrants may experience: the first one being a successful integration, the second one a downward mobility, where immigrants fail or refuse to incorporate into the mainstream, and a third one, called upward mobility, achieved by living and working in ethnically heterogeneous neighborhoods. Different authors have proposed a model called Racialized Place Inequality Framework (RPIF) (Burgos et al. 2017; Velez 2017), where it is argued that there are different factors that help explain the integration of the immigrants, including individual-, meso-, and macro-level variables. Among the macro-level factors, county- and state-level variables are included.

Various theories help explain RPIF. Place stratification helps understand why residential segregation developed in the US for African American and Latinos (Charles 2003; Massey and Denton 1993). Residential segregation has been linked to health outcomes (Fuentes-Mayorga and Burgos 2017). Ethnic enclave theory helps understand why sometimes ethnic concentration may help immigrants, since, by using ethnic solidarity, a business can be successful (Grenier and Perez 2003).

1.1.3. The COVID-19 Pandemic for the Hispanic Population

The higher death rate observed among the Hispanic population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Andrasfay and Goldman 2021; Laurencin et al. 2021; Riley et al. 2021) has led to a reduction in the so-called Hispanic health paradox (Saenz and Garcia 2021).

For some authors (Garcia et al. 2021b), the positive correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share is linked to three characteristics of the Hispanic population: (a) a higher risk of exposure due to occupational choices, (b) a lower quality in health care and access to health insurance due to lower wealth, and (c) the existence of a weathering process produced by continued exposure to harsh living conditions. Riley et al. (2021) also claimed that a lower access to vaccination explains the higher death rate.

1.1.4. Spatial Concentration of Deaths

Studies have documented the importance of spatial correlation in the spread of COVID-19 cases and deaths. McLaren (2021) found that, after controlling for characteristics of the US county, no correlation persists for the Hispanic population, while it persists for the Non-Hispanic Black population. Saffary et al. (2020) found a spatial correlation between deaths and the share of Non-Hispanic Black population at the level of US counties but did not find such a relation for the Hispanic population. Zhu et al. (2021) documented the existence of five nodes for the spread of COVID-19 found in the continental US among metropolitan areas and its regions of influence: New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, and Houston. Bossak and Andritsch (2022) showed that part of the importance of spatial correlation is explained by the pollution observed in metropolitan areas. Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha (2023) found positive spatial correlation for the male Hispanic population at the level of PUMAs for New York City but not for Hispanic females.

A theory that can help explain the importance of spatial concentration on health outcomes is the RPIF theory, since PUMAs are a macro measurement of spatial concentration at a level higher than the neighborhood but that may include more than one county on it. According to RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017; Velez 2017), macro structures may be linked to health outcomes, since they are linked to the segregation that immigrants face, which has been linked to increased health risk factors, educational disadvantages, concentrated urban poverty, economic disinvestments, crime, social disorder, and housing inequalities (Kasarda 1993; Massey and Denton 1993; Seitles 1998). An important aspect of applying a spatial analysis in studying health outcomes is to expand the RPIF theory to show that macro structures located near the macro structure where the individual lives may also influence health outcomes.

1.1.5. Heterogeneity in Health Outcomes by Hispanic Subgroups

Heterogeneous results in health outcomes of Hispanic subgroups have been reported in the literature. In cases of infant mortality, prematurity, and birthweight, Albrecht et al. (1996) reported better outcomes for Cubans and the worst results for Puerto Ricans. Acevedo-Garcia et al. (2007) explained that better birthweights are observed among children from Mexican women, while, for the other Hispanic subgroups, no difference is observed with respect to US-born babies. Jerant et al. (2008) compared the health status of Hispanic subgroups in the US versus the US White population. They found health advantages for foreign-born Mexicans and for US-born Cubans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans. Rodriguez et al. (2017) compared cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence among foreign-born Hispanics, US-born Hispanics, and the US Non-Hispanic White population. They found that CVD is less prevalent among the Hispanic population but more prevalent among the foreign-born Hispanic population. Garcia et al. (2018) found that US-born Puerto Ricans have a disadvantage in life expectancy, while foreign-born Cubans have better health outcomes. Garcia et al. (2019) argued that there are differences in indicators of mental health among different individuals living in the US, including Hispanics born in the US and foreign-born Hispanics, which requires that mental health interventions need to consider the specific needs of minorities and foreign-born adults. Zamora et al. (2019) showed that there are differences in cancer prevalence among different Hispanic subgroups, defined by place of birth. Garcia et al. (2021b) found that education benefits mental health, particularly more for Black men and women and US-born Hispanic women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

Because there is not a dataset that disaggregates deaths by PUMA and race, different authors have looked at the correlation between specific population shares and the total number of deaths (Brown and Ravallion 2020; Millet et al. 2020; McLaren 2021; Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha 2023). The Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs) are statistical geographic areas that partition states into geographic units containing no fewer than one hundred and no more than two hundred thousand people. They are used in this study, because they represent macro structures that are not selected by individuals, as they are chosen by Census authorities. As explained before, according to RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017), macro structures have implications in the assimilation of immigrants.

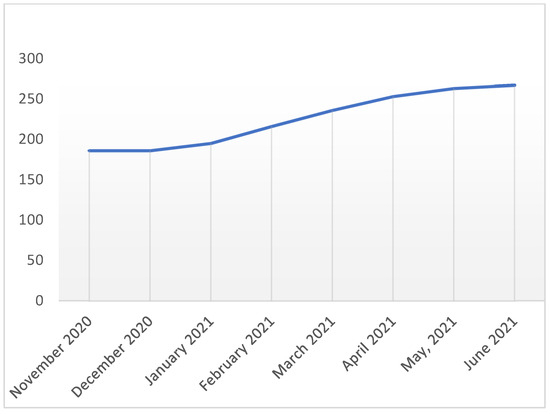

Data on mortality at the level of zip code comes from New York City Health (NYCH 2022) and includes data for the months of November 2020 through June 2021. The data were cross-walked to the PUMA level using software code available from Baruch College Newman Library (Newman 2022). The data are cross-walked and not aggregated, because each zip code is weighted by its population importance in the PUMA, and because some zip codes may be included in more than one PUMA. Consequently, the data at the PUMA level are a proxy variable for deaths occurring at that geographic location. In total, the data contain 55 PUMAs. Figure 1 shows the monthly data for New York City. A clear positive time pattern emerges. This time pattern is important, because using these data for estimations requires the usage of time-differenced data to eliminate the time trend shown in the figure (Wooldridge 2013).

Figure 1.

Monthly mean death rate by PUMA, New York City. Source: Own calculations with data from NYCH (2022).

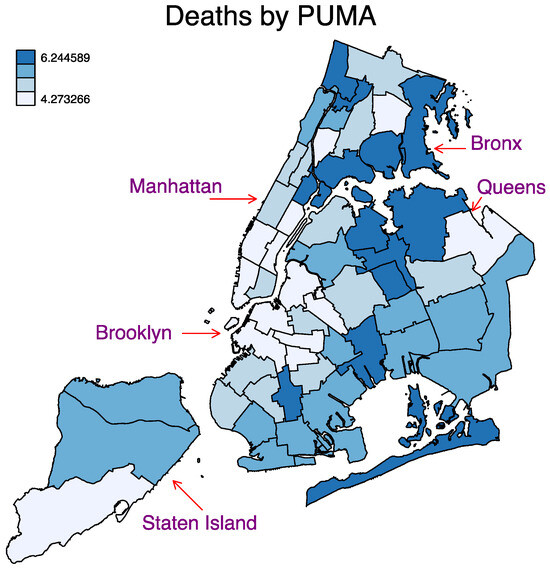

Figure 2 shows the average number of deaths per 10,000 people during the November 2020 to July 2021 period at the PUMA level.2 The figure clearly displays a spatial distribution, a fact first observed by Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha (2023). PUMAs in the areas of Queens that are close to the Bronx and Manhattan, and the corresponding adjacent areas in the Bronx and Manhattan, present some of the largest average death rates. Besides those areas, there are some additional PUMAs in Manhattan and Brooklyn that also show high death rates.

Figure 2.

Mean death rate by PUMA, November 2020–June 2021, New York City. Source: Own calculations with data from NYCH (2022).

Hispanic shares for different subgroups were aggregated at the level of PUMA from the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year public sample (Ruggles et al. 2022). These data are aggregated using inflation factors provided by ACS. Table 1 shows that the share of Hispanic subgroups in New York City. US-born Hispanics represented 60% of the total Hispanic population of New York City, Mexicans represented 21% of the Hispanic population, Salvadoreans represented 4.2% of this population, Dominicans represented 4.1%, Central Americans, excluding Salvadoreans, represented 4.6%, South Americans represented 4.3% of the population, and the rest of the foreign-born Hispanics represented 1.15% of the Hispanic population of New York City.

Table 1.

Percentages of Hispanic populations in New York City by place of birth.

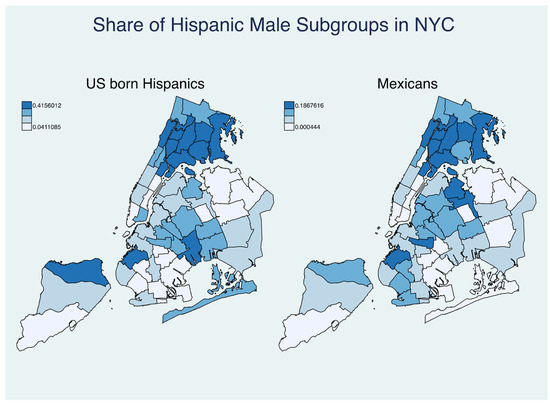

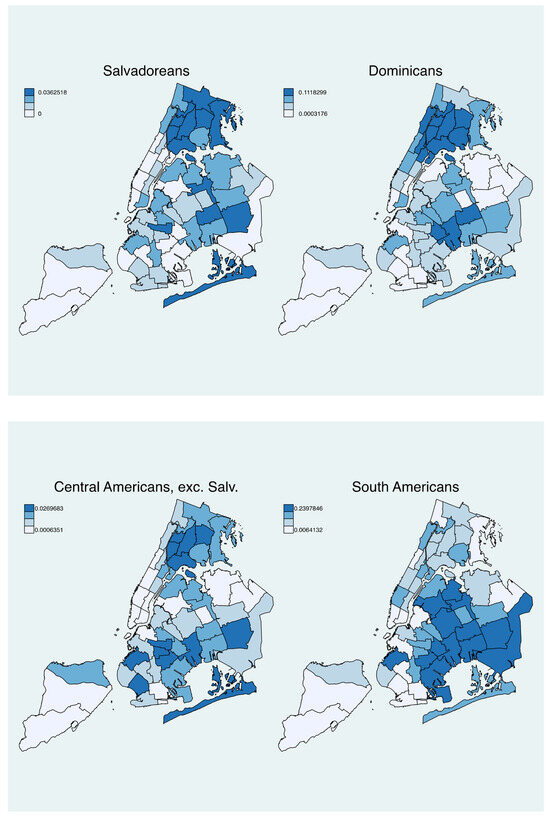

Figure 3 shows the spatial distribution for male Hispanic subgroups considered in the study. It clearly shows that there are different spatial distributions. Certain PUMAs in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx were all Hispanic subgroups showing strong concentrations, except for South Americans. In Queens, South Americans showed a strong concentration in almost all PUMAs, while only few PUMAs in that borough showed concentrations of Mexicans, Salvadoreans, Dominicans, and Central Americans. Brooklyn showed a few PUMAs with high concentrations of all the Hispanic subgroups. Staten Island only showed a spatial concentration for US-born Hispanics. These differentiated spatial concentrations imply that the different Hispanic subgroups face different macro and meso conditions, even when they share the same territory. According to RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017), this would imply potential differences in living conditions and health outcomes.

Figure 3.

Shares for different Hispanic male subgroups, New York City 2022. Source: 5% sample ACS (Ruggles et al. 2022).

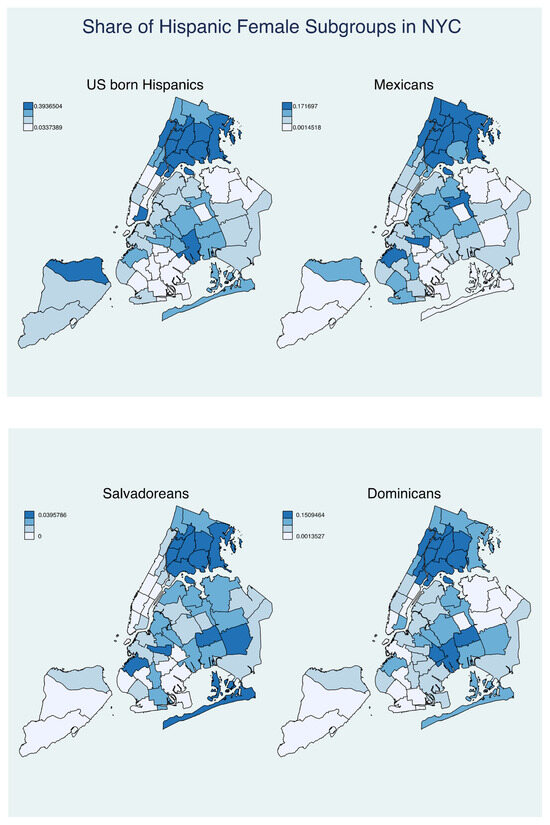

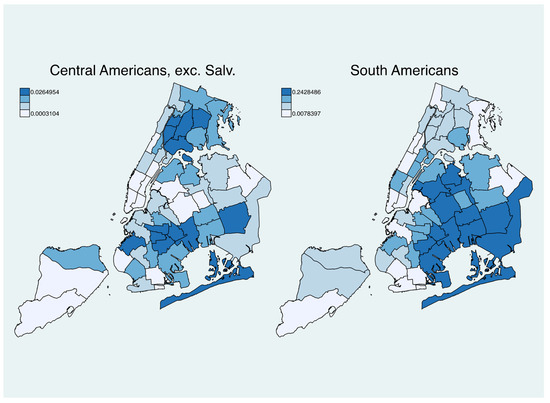

Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution for female Hispanic subgroups, and it clearly shows that the spatial distribution is different by Hispanic subgroup, and comparing the spatial distributions with those shown in Figure 3, there are also differences by gender. The differences by gender are not observed for Salvadoreans, Dominicans, Central Americans excluding Salvadoreans, or South Americans, since they show differences with other Hispanic subgroups but very similar patterns for their respective groups of males and females. The cases of US-born female Hispanics and Mexican females coincide in showing larger proportions in the north of Manhattan Borough and in the Bronx, something also observed among males of those groups. US-born Hispanic females show some concentration in the south of Manhattan, something not observed among Mexican females or males or US-born Hispanic males. Mexican females show less concentration than that observed by Mexican males in Queens and Brooklyn. So far, these findings of differentiated patterns of spatial concentration by gender have not been noted in the literature.

Figure 4.

Shares for different Hispanic female subgroups, New York City 2022. Source: 5% sample ACS (Ruggles et al. 2022).

Table 2 presents the average values for different variables at the level of the PUMAs. The median income in 2019 was 29,000 USD, and US-born Hispanics represented 20% of the population; Mexicans represented 7.5%; and Salvadoreans, Dominicans, South Americans, Central Americans excluding Salvadoreans, and the rest of the foreign-born Hispanics represented all less than 2% of the population. In the case of high school education, 56% of the population had that level of education, while college was observed in 22% of the population. The population that drives to work represented 26%, and 3.7% were unemployed. The more common occupation was services, with 14% of the population employed in such occupations, while the smallest proportion of individuals worked in farming and the military, with less than 1% of the population each. The table also shows that 45% of the population rents, 75% have more than one individual per room, and 21% of households have children living under or at the poverty line.

Table 2.

Mean values for the selected variables at the level of PUMAs.

2.2. Methods

In this paper, the approach of McLaren (2021) and Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha (2023) is expanded to indirectly estimate the differential mortality ratio between each one of the seven Hispanic subgroups studied and the rest of the population. These seven groups are determined by looking at the Hispanic groups by country of origin in New York City that represent at least four% of the Hispanic population, except for the group of other foreign-born Hispanics, which represent only 1.1% of the Hispanic population of New York City. The other groups are US-born Hispanics, Mexicans, Salvadoreans, Dominicans, Central Americans excluding Salvadoreans, and South Americans. The method consists of estimating the partial correlation between total deaths and each one of the kth specific Hispanic subgroups analyzed, as shown in Equation (1):

where represents the average death rate in PUMA i, represents the share of the kth Hispanic subgroup in PUMA i, represents the usual error term, and represents the correlation between deaths at the PUMA level and the kth Hispanic subgroup. Define H as the Hispanic share of the population as the aggregation of the 7 Hispanic subgroups studied:

The total population, in percentage terms, is then given by

where represents the non-Hispanic population. Notice that, for each Hispanic subgroup kth, Equation (3) can be rewritten as

where is the kth Hispanic subgroup, and is the rest of the Hispanic subgroups, excluding subgroup k. Now, define the average weighted death rate as

where represents deaths among the kth Hispanic subgroup in PUMA i, and represents deaths among the non-Hispanic population in PUMA i.

Using (4) in (5), we can obtain

where represents deaths among the Hispanic subgroups, excluding the kth Hispanic subgroup, in PUMA i.

Differentiating Equations (1) and (6) with respect to ,

which implies that

is the death mortality differential for the kth Hispanic group. In this paper, it is argued that the sign of this differential can provide evidence for the type of assimilation that has taken place in New York City for the kth Hispanic subgroup, taking into consideration the different types of assimilation that are predicted in Segmented Assimilation Theories (Portes and Zhou 1993). If , the kth Hispanic group has a higher mortality ratio than the non-Hispanic population, which is consistent with a downward assimilation. If , the kth Hispanic group has a lower death prevalence, which is consistent with upward assimilation. If , then the kth Hispanic subgroup has no difference with respect to the rest of the population and, consequently, has assimilated in a classical way, since immigrants have become indistinguishable from the main White population (Gordon 1964).

Given the panel data structure of our data for deaths and the cross-section nature of the data on the PUMA characteristics, this paper estimates a random effect model on the change in death rate by PUMA:

where represents control variable m for PUMA i, is the fraction for the kth Hispanic group in PUMA i, and is the faction of the Hispanic population excluding Hispanic group k. As control variables, the model includes the share of the population with some college or more education, the share of the population with high school completed, the shares of the population working in 13 occupation categories, the median household income, the share of insured population, the share of the population that drives to work, the share of unemployed population, the share of the population that rents, the share of overcrowded households, and the fraction of households with child poverty. These variables have been used in previous studies as indicators of socioeconomic risk factors for COVID-19 (Brown and Ravallion 2020; McLaren 2021) and social deprivation, a factor that has been associated with the Townsend Index (Townsend et al. 1988) and with geographic areas with high health problems (Nagaraja 2015). Using the data on the first difference of the death rate has the advantage of eliminating time trends, which the data in the levels possess, as shown in Figure 1. Time trends generate biased estimations in regression analyses (Wooldridge 2013).

Equation (10) can be rewritten to exploit the spatial distribution of the data. Specifically,

where includes all control variables and the Hispanic share for groups k, , and the rest of the Hispanic population ; includes the spatial lags; are spatial weighting matrices; and are scalar parameters. In this specification, each variable is said to have a direct and an indirect effect (Kelejian and Prucha 1999). For our specific model, the direct effect refers to the impact that each variable has on the number of deaths in each of the kth PUMAs. From a theoretical point of view, this would correspond to the effect of a macro-level factor on a health outcome, as RPIF argues (Burgos et al. 2017). The indirect effect corresponds to the effect on the number of deaths that can be traced back to PUMAs that are adjacent to the kth PUMA. RPIF does not explicitly consider these effects, but this paper argues that macro-level effects may be decomposed into those effects that consider the macro area where the immigrants live and those effects in the macro areas surrounding the kth macro area. According to RPIF, the spatial concentration may be a risk factor if individuals have isolated themselves in the “barrio” and are being exposed to bad living conditions for long time (Burgos and Rivera 2012). However, it can be a beneficial factor if living in ethnically concentrated areas allows individuals to exploit ethnic solidarity and achieve better health economic and social outcomes (Velez and Burgos 2010).

Exploiting the spatial panel nature of the data has certain advantages over an OLS estimation. First, by considering the spatial correlation, the spatial correlation model obtains a better estimation than the one offered by OLS. This is because the model explicitly takes into consideration the spatial correlation and obtains estimations for it, leading to robust and consistent estimators (Kelejian and Prucha 1999). Second, the spatial specifications allow us to obtain the direct and indirect effects. The direct effects are those estimated at the level of the PUMA, while the indirect effects include the spillover effects estimated in other PUMAs (Kelejian and Prucha 1999).

3. Results

3.1. Estimations for Men and Women

Table 3 presents the results for the correlation between the Hispanic subgroups and the change in death rates at the PUMA level for men. The first part of Table 3 shows estimations with no control variables, no spatial correlations, and for the changes in the number of monthly deaths. A positive correlation is observed for US-born Hispanics and Mexicans, but it is not found among any of the other Hispanic subgroups. This finding coincides in marking heterogeneity in health (Jerant et al. 2008) and life expectancy (Garcia et al. 2018) outcomes of different Hispanic subgroups.

Table 3.

Excess deaths for the male Hispanics subgroups.

The second part of Table 3 shows the estimations with control variables, spatial correlations for the changes in the number of monthly deaths at the PUMA level. The positive correlation vanishes for US-born Hispanics, which implies that, once the characteristics of the PUMA are taken into consideration, the group shows signs of assimilation. This implies that, for this group, macro-level factors explain their differential health outcomes, something predicted by RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017). In the case of Mexican men, the direct effect is positive and significant, but the total effect is not. This implies that, for Mexican men, the indirect effect acts as a protective factor. Then, the PUMA where Mexicans live is a risk factor, as the downward assimilation hypothesis argues (Portes and Zhou 1993), but such an effect is counteracted by the adjacent PUMAs. This counteracting effect has not been predicted by RPIF and, as such, represents the complexity of the effects of the macro structure on immigrants. Further research is needed to better understand these complex effects. In the case of Dominican men, a positive and significant correlation emerges, which is explained both by the direct and indirect effects. These results imply that, for Dominican men, controlling for the characteristics of the PUMA and the spatial correlation reveals a state of vulnerability; this result is consistent with the downward assimilation hypothesis (Portes and Zhou 1993). In the case of other foreign-born Hispanics, a positive and significant effect is found for the direct and total effects but not for the indirect effect. These results suggest that the macro structure ends up being a risk factor for this group, which reveals a state of downward assimilation for this Hispanic subgroup (Portes and Zhou 1993). In the case of Salvadoreans and South Americans, no positive association is found between deaths and their share, which would suggest successful assimilation for those groups (Gordon 1964). In the case of Central Americans excluding Salvadoreans, a negative direct effect is found, while a nonsignificant total effect is observed. This would imply that the indirect effect generates an elimination of the positive effects observed at the PUMA level. The positive effect found on health would suggest an upward assimilation generated by ethnic concentration (Portes and Zhou 1993). However, such a positive effect on health is eliminated by the adjacent PUMAs. As explained before, the effect of the adjacent PUMAs is not considered in RPIF and highlights the complexity of the macro-level effects. Further research is needed to better understand these results. Overall, these results imply that the spatial concentration effects are heterogeneous, as the Segmented Assimilation Theory claims (Portes and Zhou 1993), since different Hispanic subgroups living in the same geographic area present different patterns of assimilation. The results also highlight the effects of the macro structure on the health outcomes, something predicted by RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017), and reveal the complexity of the effect of the macro structure.

Table 4 presents the results for the correlation between the Hispanic subgroups and the changes in death rates at the PUMA level for women. The first part of Table 4 shows no significant correlation is found for any Hispanic subgroup. The second part of Table 4 reveals that, for Mexican and Salvadorean women, once the estimation controls for the characteristics of the PUMA and the spatial correlation, positive and significant direct, indirect, and total effects emerge. The existence of a positive relation between the Hispanic subgroup shares and deaths indicates that there is evidence of downward assimilation for Mexican and Salvadorean women (Portes and Zhou 1993). No significant results are observed for other women, which would suggest that other Hispanic female subgroups are integrated in a general sense (Gordon 1964).

Table 4.

Excess deaths for the female Hispanics subgroups.

Overall, these results show the existence of heterogeneity of the results by Hispanic group and by gender, even though they face the same geographic location, as predicted by Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993). These results also highlight the importance of macro-level factors, as RPIF predicts (Burgos et al. 2017). The complexity of the macro-level factors was observed among men, but it was not observed among women, which only highlights the need for further research to understand the origins for this complexity in the macro-level factors.

3.2. Using Different Subsamples: Time in the US, Citizenship, Employment Status, Health Insurance, Singlehood, and Household Headship

Different arguments have been given for the existence of a correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share. So far, this paper has shown the heterogeneity in such results and the importance of Segmented Assimilation Theory and RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017) in helping to understand such heterogeneity. This section explores if the different explanations for the existence of a correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share influence the results obtained so far.

Table 5 shows the results for subsamples generated for individuals that have arrived in the US since the year 2000 and for individuals that are US citizens. Time of arrival to the US has been argued to be correlated with health status, according to the hypothesis of the weathering process (Garcia et al. 2021b), which argues that immigrants with less time in the US should have better health outcomes. In the case of citizenship, the argument is that it should be related positively to health outcomes because of its correlation with access to health insurance and medical services not being available for non-citizens. These results also include as a control variable the share of doctors in the PUMAs, which, in principle, is a control variable for the proximity to health professionals.

Table 5.

Excess deaths for the male Hispanics subgroups, including doctors in PUMAs, for recently immigrated and citizens.

A note of clarification needs to be established regarding US-born Hispanics. In the ACS 5% sample, it is possible to identify the US state or territory where the individual was born. Consequently, individuals born in Puerto Rico, for example, are counted as Hispanics born in US territories but could have recently immigrated to New York City. Table 5 shows that, for US-born Hispanic men, the direct effect is positive and significant. This implies that time in the US represents a protective factor for US-born Hispanics, contrary to what the weathering hypothesis would argue. In the case of Mexican men, the positive correlation disappears. These results imply that the recent immigration is a protective factor, just like the weathering hypothesis argues. In the case of Dominican men, the positive effect observed in Table 3 vanishes, and consequently, time in the US is a protective factor. For the case of Central American men, the negative correlation observed in Table 3 vanishes, which implies that time in the US is a risk factor for them. In the case of South American and Salvadorean men, no effects are observed in Table 5, as was the case in Table 3. For other foreign-born Hispanics men, the positive correlation observed in Table 3 vanishes and a negative correlation emerges in Table 5, which implies that time in the US is a protective factor. It can be concluded that, for the Hispanic subgroups, that time in the US is a protective factor; there is evidence of a general assimilation effect like that argued by Gordon (1964), since, over time, health outcomes are improving. For those immigrants that time in the US is a risk factor, evidence of downward assimilation (Portes and Zhou 1993) may be indicated and perhaps the possibility of a formation of an underclass, as Tienda (1989) argued.

The second part of Table 5 shows no effect on citizenship for US-born Hispanic men. For Mexican men, the positive correlation vanishes, which implies that citizenship is a protective factor for them. For Salvadorean men, a negative correlation appears, which implies that citizenship is a protective factor. For Dominican men, a lower positive correlation is observed in Table 5 compared to Table 3, which shows that citizenship is a protective factor for them. For Central American men, a negative correlation is observed, which shows that citizenship is a protective factor. For South American men, no effect is observed. For Hispanic men born in other foreign countries, the positive correlation observed in Table 3 vanishes, which implies that citizenship is a protective factor. In general, citizenship is a protective factor for the different Hispanic subgroups. Table 5 shows that doctor density is a risk factor for US-born Hispanics. This may indicate the need for more doctors in PUMAs where these individuals live.

Table 6 shows that, for US-born women, all effects are significant and positive. These show that recent immigration is a risk factor for them. As explained before, this group includes Puerto Ricans that may have recently immigrated to NYC. In the case of Mexican women, the indirect effect found is positive and significant but not the total effect. These results imply that time in the US is a protective factor for Mexican women. For Central American women, excluding Salvadoreans, a negative direct and total effect are found. This suggests that time in the US is a risk factor for Salvadorean women. For other women, time in the US does not alter their health outcomes. As explained before, if time in the US is a protective factor, it is an indication that assimilation is taking place over time (Gordon 1964), while, if time in the US is a risk factor, such Hispanic subgroups show indications of downward assimilation (Portes and Zhou 1993).

Table 6.

Excess deaths for the female Hispanics subgroups, including doctors in PUMAs, for recently immigrated and citizens.

The second part of Table 6 also shows the results for citizenship. For US-born Hispanic women, citizenship is a protective factor, since a negative correlation is observed for the direct, indirect, and total effects. For Mexican and Salvadorean women, citizenship represents a risk factor, since positive direct, indirect, and total effects are positive for them. This may indicate that, despite citizenship, such Hispanic subgroups present evidence of downward assimilation. No other Hispanic subgroup shows positive effects when citizenship is taken into account.

Table 7 presents the results for considering only employed individuals in the sample. In the case of Mexican and Dominican men, the direct effect of the PUMA is positive. This may indicate that their jobs are riskier and reduce their health outcomes. However, the total effect is not significant, showing that the indirect effect ends up counteracting these negative effects. These results imply that the effects of the adjacent PUMAs are beneficiary for Mexicans and Dominicans. This effect of the adjacent PUMAs may be linked to the so-called upward assimilation achieved by integrating into ethnically concentrated areas (Portes and Zhou 1993). For South Americans, negative direct, indirect, and total effects appear. These results imply that, for them, employment represents a protective factor. This may indicate that the occupations in which they are working are, in some sense, providing them the means to assimilate successfully.

Table 7.

Excess deaths for the male Hispanics subgroups, including doctors in PUMAs, by employment and health insurance status.

Table 7 also shows the effects of considering only individuals that have health insurance. For all Hispanic subgroups, except for Dominicans, having health insurance shows as a protective factor. In the case of Dominican men, it appears to be a risk factor. This may indicate problems with the quality of health insurance. Evidently, more research is needed to better understand this result. Given the results presented so far, the access to health insurance seems to be an indicator that best identifies the type of assimilation that Hispanic subgroups require to achieve health outcomes like those observed among the rest of the population. It also clearly indicates the importance of policy interventions providing access to medical insurance in New York City to uninsured populations, a policy that was implemented in the Bronx during 2019 and extended to all the city in 2020 (Pazmino 2020). Table 7 presents that, for all the Hispanic subgroups, doctor density is a protective factor.

The first part of Table 8 shows the results for women that are employed. In the case of Mexican and Dominican women, the direct effect of the PUMA is positive, which probably shows that jobs carried out by these women were riskier. However, the total effect is not significant. These results imply that the adjacent PUMAs work as protective factors, indicating the possibility of upward assimilation achieved by living in ethnically concentrated areas (Portes and Zhou 1993). For South American women, a negative factor appears in the direct, indirect, and total effects. These results show that employment for South Americans helps them achieve better health outcomes. These results suggest that employment helps South Americans achieve assimilation. No other Hispanic subgroup shows significant effects.

Table 8.

Excess deaths for the female Hispanics subgroups, including doctors in PUMAs, by employment and health insurance status.

The second part of Table 8 shows the results for females with health insurance. The table shows that, for all the Hispanic subgroups, except Dominicans, having health insurance is a protective factor. In the case of Dominican women, a positive correlation is observed, which implies that having health insurance is a risk factor. This result requires more research to understand. As in the case of men, having access to health insurance seems to be the factor most important to achieve assimilation for Hispanic subgroups, with few exceptions. Table 8 presents that, for all the female groups, doctor density is a protective factor.

4. Discussion

The first research question of the paper is to determine if the reported positive correlation between deaths and the Hispanic share is found among different Hispanic subgroups, classified by their place of birth. The study confirms the existence of a correlation between deaths by COVID-19 and the different Hispanic subgroup shares, a result that confirms those reported by Andrasfay and Goldman (2021); Laurencin et al. (2021); Riley et al. (2021); and Fuentes-Mayorga and Cuecuecha (2023). However, not all Hispanic groups show a similar sign or significance.

The second research question of the paper is to identify if there is more than one type of correlation found between deaths and the Hispanic subgroup share. It is confirmed that the results are heterogeneous for different Hispanic subgroups. The study finds a positive correlation for US-born Hispanic and Mexican men but not for the other Hispanic subgroups and not for women. Moreover, the sign and significance also depend on whether the model controls for the PUMA characteristics and the spatial correlation coefficients. These heterogeneous results confirm results reported in other health outcomes of Hispanic subgroups by Albrecht et al. (1996), Acevedo-Garcia et al. (2007), Jerant et al. (2008), Rodriguez et al. (2017), Garcia et al. (2018), and Garcia et al. (2021a). The heterogeneity in the results confirms the theoretical predictions of the Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993), which claim the possibility of finding different assimilation paths among different immigrant groups that arrive at the same geographic location.)

The third research question of the paper is to analyze if there is evidence that macro-level factors influence the health outcomes of the immigrant population. The study finds evidence of the importance of macro structures, as predicted by RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017). The study finds that the direct effects of PUMAs and those associated with the PUMA where the individuals live, may be positive, negative, or nonsignificant, which confirms that macro factors are linked to the assimilation path that each immigrant groups faces in New York. This study also shows the importance of the indirect factors, those associated with PUMAs adjacent to the one where the individual lives. These indirect factors may also be positive, negative, or nonsignificant. While RPIF does not explicitly consider these additional spatial effects, this study highlights the complexity of the effects of the macro structure and the need for further research to better understand its origins.)

Evidence of the validity of the Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993) and RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017) among women is also found, since different female Hispanic subgroups show different assimilation paths, and individual factors and macro structures are important in explaining their health outcomes. These results also highlight the need for further research to better understand how gender interacts with assimilation theories for immigrants.

The fourth research question is to study if the different explanations provided for the existence of the positive correlation between deaths by COVID-19 and the Hispanic share better explain the data than the Segmented Assimilation Theory and RPIF. The different alternative explanations are (a) the weathering hypothesis, where Garcia et al. (2021b) argued that time of arrival to the US may generate lower health status among immigrants, because living in bad conditions over time reduces their health; (b) citizenship, which has been argued as related to health outcomes (Riley et al. 2021); (c) employment, since Garcia et al. (2021b) argued that the occupations of the Hispanic population exposed them more to the COVID-19 virus and the consequences; and (d) access to health insurance, which has also been argued to be related to health outcomes (Garcia et al. 2021b). In all the cases, the results in this study show that, for some groups, those variables are risk factors, while, for others, they represent protective factors. This again provides evidence in favor of the Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993). Of particular importance in these additional results are the findings that show the importance of doctor density and access to health insurance. This study finds that doctors represent a protective factor for some groups while they represent a risk factor for some other groups. These signs are linked to whether the existence of health insurance is considered. If health insurance is considered, doctor density is a protective factor for all men and women. The importance of doctor density is related to the findings of Tchicaya et al. (2021), which showed, for France, the importance of doctor density in explaining health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Conclusions

A first general result is that there exists a correlation between deaths and the Hispanic subgroup share at the level of PUMAs in New York City. The signs and significance of such correlations depend on the Hispanic subgroup analyzed, the control variables utilized, and the subsample studied. Overall, these results show that there are different assimilation paths for immigrants arriving to a similar geographic location, as predicted by the Segmented Assimilation Theory (Portes and Zhou 1993). Similarly, the results show the importance of macro-level variables to explain the health outcomes, as RPIF (Burgos et al. 2017) argued. More generally speaking, the differences in health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups demonstrates that the advantages in health reported by the Hispanic health paradox literature (Vega et al. 2009) is heterogeneous, as previous research has shown (Jerant et al. 2008; Garcia et al. 2018), and not found in all health outcomes, including deaths by COVID-19. Further research is needed to better understand the roots for these differences, since research has argued that these differences in health outcomes may be linked to differences in dietary habits, rates of smoking (Dominguez et al. 2015), differences in cultural habits that may lead to differences in family and social support (Ruiz et al. 2016), and to meso- and macro-level factors linked to residential segregation (Burgos et al. 2017). Further research is needed to understand how these different factors influence mortality rates in general and in specific health crises like the one faced under COVID-19.

A second general result is the importance of health-related factors, like health insurance and the density of doctors, which has been recognized in the literature before (Funk and Lopez 2022), and for COVID-19 (Tchicaya et al. 2021). These elements are found to be, with few exceptions, a protective factor against COVID-19. Moreover, when the analysis focuses on individuals with health insurance, the doctor density is always a protective factor. These results suggest that achieving universal coverage of health insurance among immigrant groups is a policy that favors the assimilation of such groups. Further analysis of the importance of the NYC Care Program implemented in 2019 (NYC Care 2023) is required to better understand the benefits in saving lives that were achieved thanks to the policy. Of particular importance is to study the consequences of the approach followed by NYC Care to reach out to immigrant populations, since they based their community outreach on using the support of many nongovernmental organizations (NYC Care 2023). Considering the importance of the macro factors discovered in this research, it would be interesting to study how the density of nongovernmental organizations and its functioning may be linked to the macro structures existing in NYC.

Understanding these complex socioeconomic links may help to improve the health conditions of Hispanic subgroups and potentially help design better health public policies aimed to prevent deaths in the case of the appearance of other medical emergencies like that generated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data files are available upon request to the author at alfredo.cuecuecha@upaep.mx.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The population born in Puerto Rico is included in the analysis as Hispanics born in the US, simply because they do not face the immigration constraints imposed by US immigration policy that are common for the rest of the foreign-born Hispanic population, even though they may face discrimination and racism in the US (Velez 2017). |

| 2 | The data is processed in STATA 16. |

References

- Acevedo-Garcia, Dolores, Mah-J. Soobader, and Lisa F. Berkman. 2007. Low birthweight among US Hispanic/Latino subgroups: The effect of maternal foreign-born status and education. Social Science and Medicine 65: 2503–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, Stan L., Leslie L. Clarke, Michael K. Miller, and Frank L. Farmer. 1996. Predictors of differential birth outcomes among Hispanic subgroups in the United States: The role of maternal risk characteristics and medical care. Social Science Quarterly 77: 407–33. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42863475 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Andrasfay, Theresa, and Noreem Goldman. 2021. Reductions in 2020 US life expectancy due to COVID-19 and the disproportionate impact on the Black and Latino populations. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118: e2014746118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossak, Brian H., and Samantha Andritsch. 2022. COVID-19 and Air Pollution: A Spatial Analysis of Particulate Matter Concentration and Pandemic-Associated Mortality in the US. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Caitlin S., and Martin Ravallion. 2020. Inequality and the Coronavirus: Socioeconomic Covariates of Behavioral Responses and Viral Outcomes across US Counties. Working Paper 27549. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, Giovani, and Fernando I. Rivera. 2012. Residential segregation, socioeconomic status, and disability: A multilevel study of Puerto Ricans in the US. Centro Journal 24: 14–47. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:142123608 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Burgos, Giovani, Fernando I. Rivera, and Marc A. Garcia. 2017. Towards a theoretical framework for assessing Puerto Rican Health Inequalities: The racialized place inequality framework. Centro Journal: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies XXIX: 36–73. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Camille Z. 2003. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology 29: 167–207. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30036965 (accessed on 27 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, Kenneth, Ana Penman-Aguilar, Mang-Huei Chang, Ramal Moonesinghe, Ted Castellanos, Alfonso Rodriguez-Lainz, and Richard Schieber. 2015. Vital signs: Leading causes of death, prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and use of health services among Hispanics in the United States—2009–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64: 469–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Mayorga, Norma, and Alfredo Cuecuecha. 2023. The Most Vulnerable Hispanic Immigrants in New York City: Structural Racism and Gendered Differences in COVID-19 Deaths. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Mayorga, Norma, and Giovani Burgos. 2017. Generation X and the Future Health of Latinos. Generations 41: 58–67. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26556302 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Funk, Cary, and Mark H. Lopez. 2022. Hispanic American’s Experience with Health Care. Pew Research Center Newsletter. June 14. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/06/14/hispanic-americans-experiences-with-health-care/ (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Garcia, Marc A., Brian Downer, Chi-Tsun Chiu, Joseph L. Saenz, Kasim Ortiz, and Rebeca Wong. 2021a. Educational benefits and cognitive health life expectancies: Racial/ethnic, nativity, and gender disparities. The Georontologist 63: 330–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, Marc A., Brian Downer, Chi-Tsun Chiu, Joseph L. Saenz, Sunshine Rote, and Rebeca Wong. 2019. Racial/Ethnic and nativity differences in cognitive life expectancies among older adults in the United States. The Gerontologist 59: 281–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, Marc A., Catherine Garcia, Chi-Tsun Chiu, Mukaila Raji, and Kyriakos S. Markides. 2018. A comprehensive analysis of morbidity life expectancies among older Hispanic sub-groups in the United States: Variations by nativity and country of origin. Innovation in Aging 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, Marc A., Patricia A. Homan, Catherine Garcia, and Tyson H. Brown. 2021b. The Color of COVID-19: Structural Racism and the Disproportionate Impact of the Pandemic on Older Black and Latinx Adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 76: e75–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, Milton M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, William H. 2000. Econometric Analysis. London: Prentice Hall International. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, Guillermo, and Lisandro Perez. 2003. The legacy of Exile: Cubans in the United States. Boston: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, Arlie R. 2016. Strangers in Their Own Land. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jerant, Anthony, Rose Arellanes, and Peter Franks. 2008. Health status among US Hispanics ethnic variation, nativity, and language moderation. Medical Care 46: 709–17. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40221726 (accessed on 10 May 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, Safi U., Ahmad N. Lone, Siva H. Yedlapati, Sourbha S. Dani, Muhammad Z. Kahn, Karol E. Watson, Purvi Parwani, Fatima Rodriguez, Miguel Cainzos-Achirica, and Erin D. Michos. 2022. Cardiovascular disease mortality among Hispanic versus non-Hispanic White adults in the United States, 1999 to 2018. Journal of the American Heart Association 11: e022857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarda, John D. 1993. Inner-city concentrated poverty and neighborhood distress: 1970 to 1990. Housing Policy Debate 4: 253–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelejian, Harry H., and Ingmar R. Prucha. 1999. A generalized moments estimator for the autoregressive parameter in a spatial model. International Economic Review 40: 509–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencin, Cato T., Helen Z. Wu, Aneesah McClinton, James J. Grady, and Joanne M. Walker. 2021. Excess Deaths Among Blacks and Latinx Compared to Whites during COCID-19. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8: 783–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Douglas, and Nancy A. Denton. 1993. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, John. 2021. Racial Disparity in COVID 19 Deaths: Seeking economic roots with Census data. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 21: 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, Gregorio A., Austin T. Jones, David Benkeser, Stefan Baral, Laina Mercer, Chris Beyrer, Brian Honermann, Elise Lankiewicz, Leandro Mena, Jeffrey S. Crowley, and et al. 2020. Assessing differential impacts of Covid 19 on black communities. Annals of Epidemiology 47: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanez-Valverde, Raúl, Jacob McCauly, Rosario Isasi, Stephan Zuchner, and Olveen Carrasquillo. 2021. Revisiting the Latino epidiomologic paradox: An analysis of data from the all of us research program. Journal of General Internal Medicine 37: 4013–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraja, Chaitra H. 2015. Deprivation Indices for Census Tracts in Bronx and New York Counties. Working Paper. Gabelly School of Business. Fordham University. Available online: https://www.fordham.edu/media/review/content-assets/migrated/pdfs/jadu-single-folder-pdfs/Deprivation_Index_by_Chaitra_Nagaraja.compressed.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Newman Library [Newman]. 2022. New York City Data on Neighborhoods. Consulted on February 2022. Available online: https://guides.newman.baruch.cuny.edu/nyc_data/nbhoods (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- New York City Care [NYC Care]. 2023. Your Health Care Services. NYC Care. NYC Health & Hospitals. Available online: https://www.nyccare.nyc/your-health-care-services/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- New York City Health [NYCH]. 2022. Neighborhood Data Profiles. Consulted between November 2020 and June 2021. Available online: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-neighborhoods.page (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Pazmino, Gloria. 2020. De Blasio Says City Will Expand Free Health Care Program Spectrum News. New York City. Available online: https://ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/coronavirus/2020/06/10/de-blasio-says-city-will-expand-free-health-care-program (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1993. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1047678 (accessed on 29 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Price, Sarah N., Melissa Flores, Heidi A. Hamman, and John M. Ruiz. 2021. Ethnic differences in survival among lung cancer patients: A systematic review. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 5: pkab062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, Alicia R., Yea-Hung Chen, Ellicott C. Matthay, Maria M. Glymour, Jacqueline M. Torres, Alicia Fernandez, and Kirsten Bibins-Domingo. 2021. Excess death among Latino people in California during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Fatima, Katherine G. Hastings, Jiaqi Hu, Lenny Lopez, Mark Cullen, Robert A. Harrington, and Latha P. Palaniappan. 2017. Nativity status and cardiovascular disease mortality among Hispanic adults. Journal of the American Hearth Association 6: e007207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggles, Steven, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Megan Schouweiler, and Matthew Sobek. 2022. IPUMS USA: Version 12.0 [Dataset]. Minneapolis: IPUMS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, John M., Heidi A. Hamman, Matthias R. Mehl, and Mary F. O’Connor. 2016. The Hispanic health paradox: From epidemiological phenomenon to contribution opportunities for psychological science. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 19: 462–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, John M., Patrick Steffen, and Timothy B. Smith. 2013. Hispanic Mortality Paradox: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. American Journal of Public Health 103: e52–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, Rogelio, and Marc A. Garcia. 2021. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on older Latino mortality: The rapidly diminishing Latino paradox. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 76: e81–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffary, Timor, Oyelola A. Adegboye, Ezra Gayawan, Faiz A. M. Elfaki, Abdul Kuddus, and Royan Saffary. 2020. Analysis of COVID-19 Cases’ Spatial Dependence in US counties Reveals Health Inequalities. Frontiers of Public Health 8: 579190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitles, Marc. 1998. The perpetuation of residential racial segregation in America: Historical discrimination, modern forms of exclusion, and inclusionary remedies. Florida State University Journal of Land Use and Environmental Law 14: 89–375. Available online: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/jluel/vol14/iss1/3 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Tchicaya, Anastase, Nathalie Lorentz, Kristell Leduc, and Gaetan de Lanchy. 2021. COVID-19 mortality with regard to healthcare services availability, health risks, and socio-spatial factors at department level in France: A spatial cross-sectional analysis. PLoS ONE 16: e0256857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tienda, Marta. 1989. Puerto Ricans and the underclass debate. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 501: 105–19. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1045652 (accessed on 1 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Townsend, Peter, Peter Phillimore, and Alastair Beatie. 1988. Health and Deprivation: Inequalities and the North. London: Croom Helm. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, William A., Michael A. Rodriguez, and Elisabeth Gruskin. 2009. Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiologic Reviews 31: 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, William. 2017. A new framework for understanding Puerto Ricans’ migration patterns and incorporation. Centro: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies XXIX: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Velez, William, and Giovani Burgos. 2010. The impact of housing segregation and structural factors on the socioeconomic performance of Puerto Ricans in the United States. Centro Journal 22: 175–97. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:142193099} (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. 2013. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Mason: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora, Steven M., Paulo S. Pinheiro, Scarlet L. Gomez, Katherine G. Hastings, Latha P. Palaniappan, Jiaqi Hu, and Caroline A. Thompson. 2019. Disaggregating Hispanic American cancer mortality burden by detailed ethnicity. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 28: 1353–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Di, Xinyue Ye, and Steven Manson. 2021. Revealing the spatial shifting pattern of COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Scientific Reports 11: 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).