From Late Bloomer to Booming: A Bibliometric Analysis of Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Brief Background on the Development of WGFS in Portugal

2.1. Phase 1: Initiation (1970s–1990)

2.2. Phase 2: Consolidation (1990s)

2.3. Phase 3: Expansion in the 21st Century

3. Bibliometric Studies on WGFS

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

- Preliminary tests showed that many studies in the Biological and Health Sciences use the term “gender” as a synonym for biological sex, only disaggregating clinical trial results into “male” and “female” categories. This usage posed a significant source of false positives, artificially inflating the involvement of these areas in the results. To address this limitation, we excluded documents with “gender” in the title that were categorized in the Web of Science under specific fields of Life and Health Sciences, which were identified as the primary contributors to false positives.

- Finally, to capture other specific WGFS publications that did not meet the previous search criteria, we collected all 271 Portuguese records categorized as “Women’s Studies” in the WoS. We also included publications with “Gender Studies”, “Feminist Studies”, or “Women’s Studies” listed as their topic (WoS—TS field). The complete search query, including all search expressions used, is available in the Supplementary Materials.

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

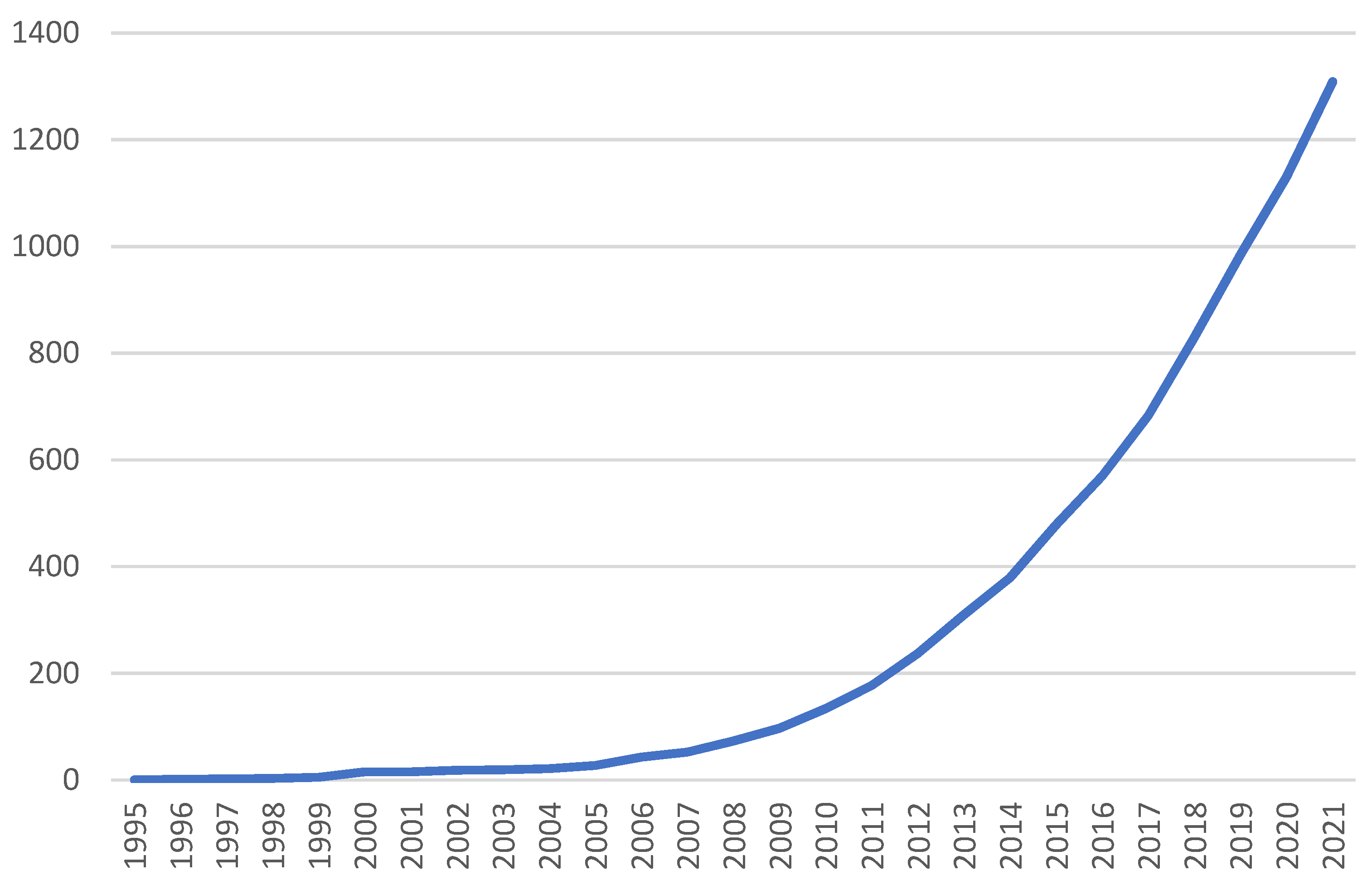

5.1. The Expansion in the 21st Century, the Impact of Productivity, and the Accentuated Internationalization of Portuguese WGFS

5.2. Languages and Document Types: The Dominance of English and Articles

5.3. Distribution of Portuguese WGFS Articles Based on the Application of Bradford’s Law: A Clear Predominance of the US and the UK

5.4. From Single Authorship and Theoretical Focus to a More Collaborative and Competitive Model of Scholarly Production

5.5. Beyond Disciplinary Limits, but with a “Narrow Interdisciplinarity” Approach, Anchored Mainly in the Social Sciences

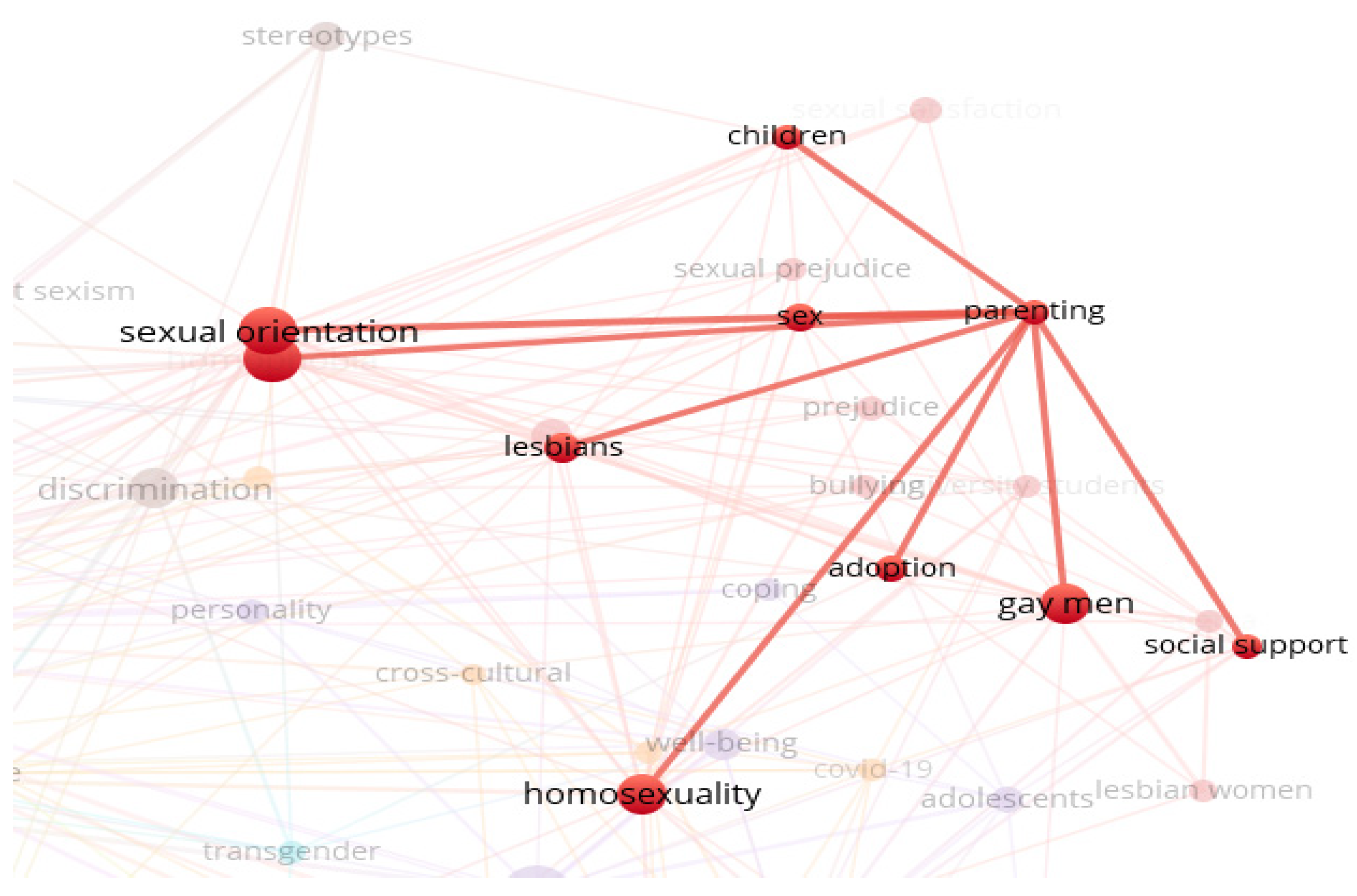

5.6. What Has Been Studied: Thematic Expansion, “Localized Internationalization”, the Growing Interest in Sexualities and Intersectionality, and the Waiving of “Women”

5.7. Influential Works: An Exogenous and Poststructuralist Intellectual Background

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Measure 8 of objective 7 of the plan was formulated in the following terms: include the interdisciplinary field of social gender relations in funding programs for scientific and technological research. |

| 2 | Our decision to use affiliation with a national institution as the indicator of association to Portuguese academia was due to the fact that the database does not have a specific filter for author’s country or nationality. We acknowledge, however, that this criterion may exclude from our results Portuguese researchers who are actively involved in WGFS but are not employed in Portugal. This factor should be carefully evaluated in future research, especially in light of the significant brain drain experienced by Portuguese academia in recent years, as highlighted in previous studies (Docquier and Marfouk 2007; Cerdeira et al. 2015). In any case, our focus was on assessing the conditions for WGFS development in the context of national higher education and R&D systems. |

| 3 | Resolution of the Council of Ministers no. 49/97 of 24 March, Diário da República, 1st series—no. 70. |

| 4 | We should also consider how the structural bias of the major virtual indexing platforms (namely Scopus and WoS) against non-English language research may contribute to these results. As several studies have shown, such databases tend to under-represent journals from outside the English-speaking Western world (Vera-Baceta et al. 2019; Tennant 2020). Consequently, it is likely that many Portuguese-language journals from lusophone countries, publishing Portuguese WGFS scholarship, are not indexed in WoS. Recently, Clarivate Analytics implemented certain positive measures to expand the reach of WoS by integrating the SciELO citation index and creating the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), which has allowed many more international titles to be included in the service (Tennant 2020, p. 2). The SciELO index, however, is not articulated to the core collection. Therefore, significant efforts are still needed to ensure that these “global” databases accurately reflect international research in all its linguistic and geographical diversity. |

References

- Abranches, Graça. 1998. On What Terms Shall We Join the Procession of Educated Men? Teaching Feminist Studies at the University of Coimbra. Oficina do CES 125: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, Herman, Young Hun Ji, and Harry Joo. 2018. Gender Productivity Gap among Star Performers in STEM and Other Scientific Fields. Journal of Applied Psychology 103: 1283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aksnes, Dag W., Kristoffer Rorstad, Fredrik Piro, and Gunnar Sivertsen. 2011. Are Female Researchers Less Cited? A Large-Scale Study of Norwegian Scientists. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 62: 628–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, Stacy. 2010. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alvanoudi, Angeliki. 2009. Teaching Gender in the Neoliberal University. In Teaching with the Third Wave: New Feminists’ Explorations of Teaching and Institutional Contexts. Edited by Daniela Gronold, Brigitte Hipfl and Linda Lund Pedersen. Utrecht: ATHENA, pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Amâncio, Lígia. 2003. O género nos discursos das ciências sociais. Análise Social XXXVIII: 687–714. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10071/18123 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Amâncio, Lígia, and João Manuel de Oliveira. 2014. Ambivalências e desenvolvimentos dos estudos de género em Portugal. Faces de Eva 32: 23–42. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10071/8956 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Angelis, Aldo D., Giacomo Scaioli, Fabrizio Bert, Roberta Siliquini, Giuseppina L. Moro, and Anna Maddaleno. 2023. Trends in LGBT+ research: A bibliometric analysis. Population Medicine 5: A1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, Carlos. 2006. Bibliometria: Evolução histórica e questões atuais. Em Questão 12: 11–32. Available online: https://seer.ufrgs.br/EmQuestao/article/view/16 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Araújo, Helena. 1997. Portugal. In European Women’s Studies Guide. Edited by Claudia Krops. Utrecht: WISE—Women’s International Studies Europe, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Archambault, Éric, Étienne Vignola-Gagne, Gregóire Côté, Vincent Larivère, and Yves Gingras. 2006. Benchmarking scientific outputs in the social sciences and humanities: The limits of existing databases. Scientometrics 68: 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arik, Engin, and Sema Akboga. 2018. Women’s Studies in the Muslim World: A Bibliometric Perspective. Publications 6: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendels, Michael H. K., Ruth Müller, Doerthe Brueggmann, and David A. Groneberg. 2018. Gender Disparities in High-Quality Research Revealed by Nature Index Journals. PLoS ONE 13: e0189136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, Sirma. 2010. Recent Feminist Outlooks on Intersectionality. Diogenes 57: 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, Samuel. 1934. Sources of Information on Specific Subjects. Engineering: An Illustrated Weekly Journal 137: 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2003. Becoming Woman: Or Sexual Difference Revisited. Theory Culture & Society 20: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrito, Belmiro Gil, Luísa Cerdeira, Ana Nascimento, and Pedro Ribeiro Mucharreira. 2021. O Ensino Superior em Portugal: Democratização e a Nova Governação Pública. Educere et Educare 15: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplar, Neven, Sandro Tacchella, and Simon Birrer. 2017. Quantitative Evaluation of Gender Bias in Astronomical Publications from Citation Counts. Nature Astronomy 1: 0141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Sónia, Teresa Carvalho, and Rui Santiago. 2011. From students to consumers: Reflections on the marketisation of Portuguese higher education. European Journal of Education 46: 271–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera Suárez, Isabel, and Laura Viñuela Suárez. 2006. The Bologna Process: Impact on Interdisciplinarity and Possibilities for Women’s Studies. NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 14: 103–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeira, Luísa, Belmiro Cabrito, Maria de Lourdes Machado Taylor, and Rui Gomes. 2015. A fuga de cérebros em Portugal: Hipóteses explicativas. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação 31: 409–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, Bobby K., Irene Melani, and Ying-yi Hong. 2020. How USA-Centric Is Psychology? An Archival Study of Implicit Assumptions of Generalizability of Findings to Human Nature Based on Origins of Study Samples. Social Psychological and Personality Science 11: 928–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2015. Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology 41: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collyer, Fran M. 2018. Global Patterns in the Publishing of Academic Knowledge: Global North, Global South. Current Sociology 66: 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Tzipi, Noa Aharony, and Judit Bar-Ilan. 2021. Gender Differences in the Israeli Academia: A Bibliometric Analysis of Different Disciplines. Aslib Journal of Information Management 73: 160–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Davide. 2023. Transgender Health between Barriers: A Scoping Review and Integrated Strategies. Societies 13: 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, Blaise, Anna Martinson, and Elisabeth Davenport. 1997. Women’s Studies: Bibliometric and Content Analysis of the Formative Years. Journal of Documentation 53: 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudina, Jean Nikola, Julio César Ossa, Elsa María Castrillón-Correa, Andrea Precht, Josiane Suelí Bería, and Fernando Andrés Polanco. 2021. What Can We Say about Gender Studies in Colombia? An Analysis from a Socio-Bibliometric Perspective. ex aequo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 44: 165–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daim, Tugrul U., Guillermo Rueda, Hilary Martin, and Pisek Gerdsri. 2006. Forecasting Emerging Technologies: Use of Bibliometrics and Patent Analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 73: 981–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daune-Richard, Anne-Marie, and Anne-Marie Devreux. 1990. La Reproduction Des Rapports Sociaux de Sexe. In À Propos des Rapports Sociaux de Sexe. Edited by Françoise Battagliola. Paris: IRESCO, Centre de Sociologie Urbaine. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Kathy, Mary Evans, and Judith Lorber. 2006. Handbook of Gender and Women’s Studies. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, Debora, and Paula Foltran. 2004. Gênero e feminismo no Brasil: Uma análise da Revista Estudos Feministas. Revista Estudos Feministas 12: 245–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, Michelle L., Jane Lawrence Sumner, and Sara McLaughlin Mitchell. 2018. Gendered Citation Patterns across Political Science and Social Science Methodology Fields. Political Analysis 26: 312–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docquier, Frédéric, and Abdeslam Marfouk. 2007. Brain Drain in Developing Countries. World Bank Economic Review 21: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Mary. 2006. Editorial Response. European Journal of Women’s Studies 13: 309–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ex æquo Editorial Board. 1999. Editorial. ex æquo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 1: 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Falquet, Julie. 2012. Les mouvements sociaux dans la mondialisation néolibérale: Imbrication des rapports sociaux et classe des femmes (Amérique Latine-Caraïbes-France). Ph.D. thesis, Université de Paris VIII, Paris, France. Available online: https://sudoc.abes.fr/cbs/xslt/DB=2.1//SRCH?IKT=12&TRM=183121708 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Ferreira, Eduarda. 2019. Women’s, Gender and Feminist Studies in Portugal: Researchers’ Resilience vs Institutional Resistance. Gender, Place & Culture 26: 1223–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Virgínia. 2001. Estudos sobre as Mulheres em Portugal. A construção de um novo campo científico. ex æquo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 5: 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Virgínia. 2013. «L’usage du genre au Portugal: En tant que catégorie analytique ou descriptif?». Fédération de recherche sur le genre RING. June 25. Available online: http://www2.univparis8.fr/RING/spip.php?article2739 (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Ferreira, Virgínia, Cristina C. Vieira, Maria João Silveirinha, Elizângela Carvalho, and Priscila Freire. 2020. Estudos sobre as Mulheres em Portugal pós-Declaração de Pequim—Estudo bibliométrico das revistas ex æquo e Faces de Eva. ex æquo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 42: 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Virgínia, Teresa Tavares, and Clara Lourenço. 2001. Número Especial ‘A construção dos Estudos sobre as Mulheres em Portugal’. ex æquo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres. Available online: https://exaequo.apem-estudos.org/revista/revista-ex-aequo-numero-05-2001 (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Foucault, Michel. 1979. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 1st ed. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frogeri, Rodrigo Franklin, Fabrício Ziviani, Aline de Paula Martins, Thaís Campos Maria, and Rubia Magalhães Fraga Zocal. 2022. O Grupo de Trabalho 4 do ENANCIB: Uma análise bibliométrica. Perspectivas em Gestão & Conhecimento 12: 235–52. Available online: https://periodicos.ufpb.br/ojs2/index.php/pgc/article/view/62824 (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Glick, Peter, and Susan T. Fiske. 1996. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating Hostile and Benevolent Sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, Benoît. 2006. On the Origins of Bibliometrics. Scientometrics 68: 109–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, David, and Louise Deis. 2007. Update on Scopus and Web of Science. The Charleston Advisor 7: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grünell, Marianne, and Erna Kas. 1995. Modernization and Emancipation from Above. European Journal of Women’s Studies 2: 535–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2016. Intersectionality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hark, Sabine. 2007. Magical Sign. On the Politics of Inter- and Transdisciplinarity. Graduate Journal of Social Science 4: 11–33. Available online: http://gjss.org/sites/default/files/issues/chapters/papers/Journal-04-02--01-Hark.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Haustein, Stefanie, and Vincent Larivière. 2015. The Use of Bibliometrics for Assessing Research: Possibilities, Limitations and Adverse Effects. In Incentives and Performance: Governance of Research Organizations. Edited by Isabell M. Welpe, Jutta Wollersheim, Stefanie Ringelhan and Margit Osterloh. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 121–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings, Clare. 2006. Ready for Bologna? The Impact of the Declaration on Women’s and Gender Studies in the UK. European Journal of Women’s Studies 13: 315–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hérubel, Jean-Pierre V. M. 1999. Review: Historical Bibliometrics: Its Purpose and Significance to the History of Disciplines. Libraries & Culture 34: 380–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppen, Natascha Helena Franz. 2021. Retratos da pesquisa brasileira em estudos de gênero: Análise cientométrica da produção científica. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Available online: https://lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/220744 (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Hoppen, Natascha Helena Franz, and Samile Andrea de Souza Vanz. 2020. O que são estudos de gênero: Caracterização da produção científica autodenominada estudos de gênero em uma base de dados multidisciplinar e internacional. Encontros Bibli: Revista Eletrônica de Biblioteconomia e Ciência da Informação 25: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppen, Natascha Helena Franz, and Samile Andréa de Souza Vanz. 2023. The Development of Brazilian Women’s and Gender Studies: A Bibliometric Diagnosis. Scientometrics 128: 227–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Zhigang, Wencan Tian, Shenmeng Xu, Chunbo Zhang, and Xianwen Wang. 2018. Four Pitfalls in Normalizing Citation Indicators: An Investigation of ESI’s Selection of Highly Cited Papers. Journal of Informetrics 12: 1133–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huutoniemi, Katri, Julie Thompson Klein, Henrik Bruun, and Janne Hukkinen. 2010. Analyzing Interdisciplinarity: Typology and Indicators. Research Policy 39: 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquim, Teresa. 2004. ex æquo: Contributo decisivo para um campo de estudos em Portugal. Revista Estudos Feministas 12: 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahalon, Rotem, Verena Klein, Inna Ksenofontov, Johannes Ullrich, and Stephen C. Wright. 2022. Mentioning the Sample’s Country in the Article’s Title Leads to Bias in Research Evaluation. Social Psychological and Personality Science 13: 352–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataeva, Zumrad, Naureen Durrani, Zhanna Izekenova, and Aray Rakhimzhanova. 2023. Evolution of Gender Research in the Social Sciences in Post-Soviet Countries: A Bibliometric Analysis. Scientometrics 128: 1639–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kergoat, Danièle. 2012. Se Battre, Disent-Elles…. Paris: La Dispute (Collection: Le genre du monde). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Weishu. 2021. A Matter of Time: Publication Dates in Web of Science Core Collection. Scientometrics 126: 849–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Weishu, Li Tang, and Guangyuan Hu. 2020. Funding Information in Web of Science: An Updated Overview. Scientometrics 122: 1509–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykke, Nina. 2000. Towards an Evaluation of Women’s Studies in Relation to the Job Prospects of Its Graduates. In The Making of European Women’s Studies. Utrecht: ATHENA, vol. I, pp. 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, Ana Gabriela, and Francesca Rayner, eds. 2011. Género, cultura visual e performance: Antologia crítica. Braga: CEHUM/Húmus. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, Ana Gabriela, ed. 2002. Género, identidade e desejo: Antologia crítica do feminismo contemporâneo. Lisboa: Cotovia. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, Leslie. 2005. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 30: 1771–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, Arthur Jack. 1999. A Comunicação Científica. Brasília: Briquet de Lemos. [Google Scholar]

- Messer-Davidow, Ellen. 2002. Disciplining Feminism: From Social Activism to Academic Discourse. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mira, Rita. 2013. (Entrevista com) Teresa Pinto. Faces de Eva—Estudos sobre as Mulheres 30: 137–44. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, Rosa. 2011. Feminismo de Estado em Portugal: Mecanismos, estratégias, políticas e metamorfoses. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, Josilene Aires, and Catarina Sales Oliveira. 2022. Quantifying for Qualifying: A Framework for Assessing Gender Equality in Higher Education Institutions. Social Sciences 11: 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, Jennifer C. 2008. Re-Thinking Intersectionality. Feminist Review 89: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Maria do Mar. 2008. The Epistemic Status of Women’s, Gender, Feminist Studies: Notes for Analysis. In The Making of Women’s Studies. Edited by Berteke Waaldijk, Mischa Peters and Else van der Tuin. Utrecht: ATHENA, vol. VIII. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Maria do Mar. 2013. A institucionalização dos Estudos sobre as Mulheres, de Género e Feministas em Portugal no século XXI: Conquistas, desafios e paradoxos. Faces de Eva—Estudos sobre as Mulheres 30: 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Maria do Mar. 2014. The Importance of Being ‘Modern’ and Foreign: Feminist Scholarship and the Epistemic Status of Nations. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 39: 627–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Maria do Mar. 2017. Power, Knowledge and Feminist Scholarship: An Ethnography of Academia. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Maria do Mar. 2018. The Institutionalisation of Gender Studies and the New Academic Governance: Longstanding Patterns and Emerging Paradoxes. In Gender Studies and the New Academic Governance. Global Challenges, Glocal Dynamics, and Local Impacts. Edited by Heike Kahlert. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Maria do Mar, and Ana Cristina Santos. 2014. Introdução. Epistemologias e metodologias feministas em Portugal: Contributos para velhos e novos debates. ex aequo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 29: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Teresa. 2008. A formação profissional das mulheres no ensino industrial público (1884–1910): Realidades e representações. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Aberta, Lisboa, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorioaberto.uab.pt/handle/10400.2/1334 (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Pinto, Teresa. 2015. A APEM e os Estudos sobre as Mulheres e de Género em Portugal: Contextos e percursos. In Estudos de género numa perspetiva interdisciplinar. Edited by Anália Torres, Helena Sant’Ana and Diana Maciel. Lisboa: Mundos Sociais, pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, Alan. 1969. Statistical Bibliography or Bibliometrics? Journal of Documentation 25: 348–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, Maria Irene. 2001. Os Estudos sobre as Mulheres e o saber. Onde se conclui que o poético é feminista. ex aequo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 5: 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, Maria Irene. 2009. SIGMA National Report: Portugal. In The Making of European Women’s Studies. Edited by Berteke Waaldijk and Else van Der Tuin. Utrecht: ATHENA, vol. IX, pp. 119–36. First published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert, Sybille, and Christian Tauch. 2005. Trends IV: European Universities Implementing Bologna. Brussels: European University Association. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Caynnã de Camargo, Mónica do Adro Lopes, Cristina Coimbra Vieira, and Virgínia Ferreira. 2022. O que se ensina nos Estudos de Género em Portugal: Uma análise bibliométrica dos planos curriculares. Encontros Bibli: Revista Eletrônica de Biblioteconomia e Ciência da Informação 27: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silius, Harriet. 2002. Women’s Employment, Equal Opportunities and Women’s Studies in Nine European Countries—A Summary. In Women’s Employment, Women’s Studies, and Equal Opportunities 1945–2001. Edited by Gabrielle Griffin. Hull: University of Hull, pp. 15–64. [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund, Therese, and Guy Madison. 2015. Characteristics of Gender Studies Publications: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on a Swedish Population Database. Scientometrics 105: 1347–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, Maria Manuela Paiva Fernandes. 2008. Feminismos em Portugal (1927–2007). Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Aberta, Lisboa, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorioaberto.uab.pt/handle/10400.2/1346 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Tennant, Jonathan P. 2020. Web of Science and Scopus are not global databases of knowledge. European Science Editing 46: 2020. Web of Science and Scopus are not global databases of knowledge. European Science Editing 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Anália, Helena Sant’Ana, and Diana Maciel. 2015. Introdução. In Estudos de género numa perspetiva interdisciplinar. Edited by Anália Torres, Helena Sant’Ana and Diana Maciel. Lisboa: Mundos Sociais, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tsay, Ming-yueh, and Chia-ning Li. 2017. Bibliometric Analysis of the Journal Literature on Women’s Studies. Scientometrics 113: 705–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 1995. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Beijing: United Nations. Available online: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA%20E.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 84: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquinhas, Irene. 2002. Linhas de investigação para a História das mulheres no século XIX e XX. História: Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto 3: 201–21. Available online: https://ojs.letras.up.pt/index.php/historia/article/view/5120 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Varikas, Eleni. 2006. GRACE Report: Women’s Studies in Greece 1988. In The Making of European Women’s Studies. Edited by Rosi Braidotti and Berteke Waaldijk. Utrecht: ATHENA, vol. VII, pp. 159–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Baceta, Miguel-Angel, Michael Thelwall, and Kayvan Kousha. 2019. Web of Science and Scopus Language Coverage. Scientometrics 121: 1803–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, Cristina C. 2007. A dimensão de género nos curricula do ensino superior: Factos e reflexões a partir de uma entrevista focalizada de grupo a especialistas portuguesas no domínio. ex-aequo—Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Estudos sobre as Mulheres 16: 167–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wedgwood, Nikki, Raewyn Connell, and Julian Wood. 2022. Deploying Hegemonic Masculinity: A Study of Uses of the Concept in the Journal Psychology of Men & Masculinities. Psychology of Men & Masculinities. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Bitnari, June Young Lee, and Sejung Ahn. 2020. The Intellectual Structure of Women’s Studies: A Bibliometric Study of Its Research Topics and Influential Publications. Asian Women 36: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, Susan. 2008. The Institutionalization of Women’s and Gender Studies in Higher Education in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union: Asymmetric Politics and the Regional-Transnational Configuration. East Central Europe 34–35: 131–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zones | Number of Journals | Number of Articles | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 43 | 277 | 33.4% |

| II | 162 | 277 | 33.4% |

| III | 276 | 276 | 33.3% |

| Total | 481 | 830 |

| Authors per Work 1995–2004 (n = 21) | Authors per Work 2005–2014 (n = 358) | Authors per Work 2015–2021 (n = 930) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n Authors | n Work | % | n Authors | n Work | % | n Authors | n Work | % |

| 1 | 10 | 47.6% | 1 | 119 | 33.2% | 1 | 230 | 24.7% |

| 2 | 2 | 9.5% | 2 | 81 | 22.6% | 2 | 195 | 21.0% |

| 3 | 1 | 4.8% | 3 | 71 | 19.8% | 3 | 192 | 20.6% |

| 4 | 1 | 4.8% | 4 | 39 | 10.9% | 4 | 122 | 13.1% |

| 5 | 1 | 4.8% | 5 | 15 | 4.2% | 5 | 74 | 8.0% |

| 6 | 4 | 19.0% | 6 | 11 | 3.1% | 6 | 49 | 5.3% |

| 7 or + | 2 | 9.5% | 7 or + | 22 | 6.1% | 7 or + | 68 | 7.3% |

| Research Areas (n = 1309) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areas | n Works | % | Areas | n Works | % |

| Women’s Studies | 270 | 20.60% | History | 41 | 3.10% |

| Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | 140 | 10.70% | Business | 40 | 3.10% |

| Public, Environmental and Occupational Health | 123 | 9.40% | Communication | 34 | 2.60% |

| Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 109 | 8.30% | Economics | 32 | 2.40% |

| Education and Educational Research | 101 | 7.70% | Humanities, Multidisciplinary | 32 | 2.40% |

| Social Issues | 74 | 5.70% | Psychology, Developmental | 25 | 1.90% |

| Psychiatry | 66 | 5.00% | Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism | 23 | 1.80% |

| Sociology | 57 | 4.40% | Area Studies | 21 | 1.60% |

| Psychology, Clinical | 55 | 4.20% | Cultural Studies | 21 | 1.60% |

| Management | 51 | 3.90% | Law | 21 | 1.60% |

| Psychology, Social | 49 | 3.70% | Criminology and Penology | 19 | 1.50% |

| Family Studies | 44 | 3.40% | |||

| Areas 1995–2004 (n = 21) | Areas 2005–2014 (n = 358) | Areas 2015–2021 (n = 930) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areas | n Works | % | Areas | n Works | % | Areas | n Works | % |

| Psychology, Developmental | 4 | 19.0% | Women’s Studies | 91 | 25.4% | Women’s Studies | 176 | 18.9% |

| Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 3 | 14.3% | Public, Environmental and Occupational Health | 48 | 13.4% | Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | 104 | 11.2% |

| Women’s Studies | 3 | 14.3% | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 38 | 10.6% | Public, Environmental and Occupational Health | 74 | 8.0% |

| Literature | 2 | 9.5% | Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | 35 | 9.8% | Education and Educational Research | 71 | 7.6% |

| Psychology, Social | 2 | 9.5% | Education and Educational Research | 30 | 8.4% | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 68 | 7.3% |

| Psychiatry | 2 | 9.5% | Sociology | 26 | 7.3% | Social Issues | 56 | 6.0% |

| History | 2 | 9.5% | Psychiatry | 21 | 5.9% | Psychology, Clinical | 48 | 5.2% |

| Communication | 2 | 9.5% | Social Issues | 17 | 4.7% | Psychiatry | 43 | 4.6% |

| Virology | 1 | 4.8% | History | 17 | 4.7% | Management | 38 | 4.1% |

| Sociology | 1 | 4.8% | Psychology, Social | 14 | 3.9% | Family Studies | 38 | 4.1% |

| Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | 1 | 4.8% | ||||||

| Cluster | Label | n Keywords | Core Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Non-normative Sexualities | 18 | Sexual orientation; homophobia; gay men |

| C2 | Physical and Mental Health | 12 | Depression; anxiety; COVID-19 |

| C3 | Gender and Youth | 12 | Gender differences; adolescence; well-being |

| C4 | Gender and Culture | 11 | Portugal; Brazil; media |

| C5 | Politics and Identity | 10 | Feminism; identity; women |

| C6 | Contemporary Labor Relations and Gender | 10 | Gender; higher education; entrepreneurship |

| C7 | Intersectionality | 9 | Intersectionality; gender studies; migration |

| C8 | Gender Inequalities in Different Contexts | 7 | Education; gender equality; diversity |

| C9 | Sexism and discrimination | 6 | Discrimination; sexism; stereotypes |

| Keywords 2005–2014 (n = 209) | Keywords 2015–2021 (n = 679) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author Keywords | Occurrences | % | Author Keywords | Occurrences | % |

| Gender | 71 | 34.00% | Gender | 182 | 26.80% |

| Portugal | 23 | 11.00% | Portugal | 60 | 8.80% |

| Women | 11 | 5.30% | Gender Differences | 27 | 4.00% |

| Gender Differences | 8 | 3.80% | Sexual Orientation | 19 | 2.80% |

| Higher Education | 8 | 3.80% | Women | 18 | 2.70% |

| Homosexuality | 7 | 3.30% | Homophobia | 17 | 2.50% |

| Discrimination | 7 | 3.30% | Gender Equality | 17 | 2.50% |

| Feminism | 6 | 2.90% | Education | 15 | 2.20% |

| HIV | 6 | 2.90% | Higher Education | 14 | 2.10% |

| Prejudice | 5 | 2.40% | Intersectionality | 13 | 1.90% |

| Gender Identity | 5 | 2.40% | Gender Studies | 13 | 1.90% |

| Attitudes | 5 | 2.40% | Gay Men | 12 | 1.80% |

| Family | 4 | 1.90% | Depression | 12 | 1.80% |

| Migration | 4 | 1.90% | Feminism | 12 | 1.80% |

| Emotions | 4 | 1.90% | Diversity | 11 | 1.60% |

| Gender Studies | 4 | 1.90% | Discrimination | 11 | 1.60% |

| Depression | 4 | 1.90% | Brazil | 10 | 1.50% |

| Class | 4 | 1.90% | Well-Being | 10 | 1.50% |

| Sex | 4 | 1.90% | Adolescence | 10 | 1.50% |

| Stereotypes | 10 | 1.50% | |||

| Occurrences | Cited Reference | Title | Publication Medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | Butler, Judith (1990) | Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity | Book |

| 32 | Meyer, Ilan H (2003) | “Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence” | Psychological Bulletin |

| 31 | Braun, Virginia, and Clarke, Victoria (2006) | “Using thematic analysis in psychology” | Qualitative Research in Psychology |

| 26 | Hu, Li-tze, and Bentler, Peter M. (1999) | “Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives” | Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal |

| Glick and Fiske (1996) | “The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism” | Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | |

| 25 | Crenshaw (1991) | “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color” | Stanford Law Review |

| 22 | Connell, Raewyn (1995) | Masculinities | Book |

| West, Candace, and Zimmerman, Don H. (1987) | “Doing Gender” | Gender and Society | |

| Connell, Raewyn (1987) | Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics | Book | |

| 21 | Butler, Judith (2004) | Undoing Gender | Book |

| 20 | Cohen, Jacob (1988) | Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences | Book |

| Fornell, Claes, and Larcker, David F. (1981) | “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error” | Journal of Marketing Research | |

| Cheung, Gordon W., and Rensvold, Roger B. (2002) | “Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance” | Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal | |

| 18 | Acker, Joan (1990) | “Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations” | Gender and Society |

| Amâncio, Lígia (1994) | Masculino e feminino. A construção social da diferença | Book | |

| Nogueira, Conceição, and Oliveira, João Manuel de (2010) | Estudo sobre a discriminação em função da orientação sexual e da identidade de género | Book | |

| 17 | Rosen, Raymond et al. (2000) | “The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A Multidimensional Self-Report Instrument for the Assessment of Female Sexual Function” | Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy |

| 16 | Hofstede, Geert (2001) | “Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations” | Book |

| 15 | Connell, Raewyn (2002) | Gender | Book |

| Amâncio, Lígia, and Oliveira, João Manuel de (2006) | “Men as Individuals, Women as a Sexed Category: Implications of Symbolic Asymmetry for Feminist Practice and Feminist Psychology” | Feminism and Psychology | |

| Connell, Raewyn (2005) | “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept” | Gender and Society |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, C.; Monteiro, R.; Lopes, M.; Martinez, M.; Ferreira, V. From Late Bloomer to Booming: A Bibliometric Analysis of Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Portugal. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070396

Santos C, Monteiro R, Lopes M, Martinez M, Ferreira V. From Late Bloomer to Booming: A Bibliometric Analysis of Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Portugal. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(7):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070396

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Caynnã, Rosa Monteiro, Mónica Lopes, Monise Martinez, and Virgínia Ferreira. 2023. "From Late Bloomer to Booming: A Bibliometric Analysis of Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Portugal" Social Sciences 12, no. 7: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070396

APA StyleSantos, C., Monteiro, R., Lopes, M., Martinez, M., & Ferreira, V. (2023). From Late Bloomer to Booming: A Bibliometric Analysis of Women’s, Gender, and Feminist Studies in Portugal. Social Sciences, 12(7), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070396