Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers (HCWs) did not have the opportunity to provide high-quality and standard healthcare services. Research conducted during the pandemic has revealed widespread mental health problems among HCWs. Moral distress was noted as one of the critical issues that limited the performance of HCWs in providing quality care. The purpose of this scoping review was to create an overview of HCWs’ moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. The review was conducted according to the Arksey and O’Malley framework. A systematic literature search was performed in five database systems: Medline/PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, ProQuest, and the Cochrane Library, according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Relevant article titles and abstracts were retrieved. The final review included 16 publications identifying the moral distress of HCWs during the pandemic. In total, five themes characterizing the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified: (1) a level of moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) risk factors for moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) moral and ethical dilemmas during the COVID-19 pandemic; (4) harm caused by moral distress to HCWs; and (5) intervention methods for reducing moral distress. The pandemic turned a health emergency into a mental health emergency for HCWs.

1. Introduction

A disease originating in China and named after 2019, i.e., COVID-19, emerged as a threat to global health (Wang et al. 2020). After its rapid spread to several countries in January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern, which became a global pandemic on 11 March 2020 (Cucinotta and Vanelli 2020). Within a few weeks of declaring the COVID-19 pandemic an international disease, it became clear that conventional public health practices would not be able to contain it (Latif et al. 2020; Luengo-Oroz et al. 2020). Massive restrictions were introduced, including remote work, social distancing, staying at home, mandatory wearing of masks, and continuous testing. Significant restrictions were introduced in the provision of scheduled and ambulatory health care services. The COVID-19 pandemic attracted enormous attention from HCWs and public health professionals, as well as experts from various scientific disciplines, who produced more than 400,000 publications about the coronavirus in 2020 (Esteva et al. 2021). The statistics of 19 May 2021 showed that the COVID-19 pandemic was a global disease to be measured in the lives of more than 3.4 million deceased people (Kim and Burić 2020). The world crisis turned into an emergency in the healthcare sector. Moral distress became a significant phenomenon among HCWs (Silverman et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2012).

Jameton (1984) was the first to describe a concept of moral distress in the context of nurses’ ethical responsibilities before, during, and after a nuclear war. The above-mentioned ones, as well as some other authors, described moral distress as a negative emotional response to a personal moral failure while practicing in one’s professional field (Jameton 1984; McCarthy and Gastmans 2015). This concept related not only to nurses or veterans, but its definition and application were also widely discussed among physicians and residents (Farrell and Hayward 2022). The above-mentioned phenomenon was common to many healthcare institutions and at multiple organizational levels, and that, in turn, had negative consequences both among HCWs and healthcare organizations (Oh and Gastmans 2015).

At the individual level, moral distress led to emotional burnout, lack of empathy, compassion fatigue, feelings of powerlessness, and dissatisfaction with professional performance. On the other hand, at the organizational level, the quality of the service provided by healthcare deteriorated, which was associated with a catastrophic lack of time and resources. An increase in employee turnover was observed (Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Hegarty et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022; Asadi et al. 2022). The number of cases in which ethical issues had to be addressed increased. Healthcare organizations often lacked standardized guidelines on how to deal with ethical dilemmas. Recent studies (Donkers et al. 2021; Petrisor et al. 2021; Silverman et al. 2021; Hegarty et al. 2022; Lemmo et al. 2022) demonstrated the relationship between ethical dilemmas experienced by healthcare professionals and moral distress. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, moral and ethical dilemmas in healthcare have risen to the top of medical priorities.

The biggest challenges for care professionals were a lack of experience in working with the COVID-19 pandemic, a lack of personal protective equipment, as well as social distancing (Dudzinski et al. 2020; Nyashanu et al. 2020). Several issues involving ethical dilemmas (Farrell and Hayward 2022) were illuminated. Ethical dilemmas occurred in situations where a complex decision that consisted of choosing between two mutually exclusive or equally complex moral options had to be made (Morley et al. 2019). HCWs faced ethical dilemmas, which included a lack of personnel resources, distribution of artificial respiratory ventilators, insufficiency of personal protective equipment, and the use of experimental therapy (Donkers et al. 2021). Although scientists provided extensive information on the spread and course of the disease, decision-making remained in the hands of doctors (Farrell and Hayward 2022). HCWs experienced ethically and morally stressful situations every day. They had to deal with increasing infection rates and workloads inadequate for existing resources (Riedel et al. 2022; Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). While working in the clinical environment, HCWs still had to face several moral and ethical dilemmas that increased moral distress (Menon and Padhy 2020), contributed to emotional burnout, and had an impact on the effectiveness of their work (Donkers et al. 2021; Smallwood et al. 2021; Kok et al. 2023; Koonce and Hyrkas 2023). Therefore, both ethical dilemmas and basic principles of morality were at odds with each other during the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic served as one of the factors that also created psychological problems and contributed to the development of moral distress (Williamson et al. 2020). HCWs experienced a high level of moral distress (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022), and therefore, various support mechanisms were developed. Very often, HCWs used the consultations offered by psychologists, the assistance of social workers, pastoral counseling, and the help of psychotherapists. Often, an immediate supervisor served as an advisor and a person who listens to and supports (Kok et al. 2023; Hines et al. 2021).

The above-mentioned clearly showed that the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant mental and physical health problems for HCWs (Donkers et al. 2021; Hegarty et al. 2022; Lemmo et al. 2022; Petrisor et al. 2021; Silverman et al. 2021). It is necessary to pay increased attention to the mental health of HCWs. Clear guidelines should be developed on how HCWs should act in emergency epidemic situations, minimizing the impact of moral distress on HCWs as much as possible. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct a scoping review of studies carried out to understand the phenomenon of moral distress among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic and to summarize possible intervention methods for reducing the moral distress of HCWs. The obtained data will provide an opportunity to develop a set of preventive measures for medical institutions with the purpose to reduce mental health problems caused by moral distress among HCWs.

The purpose of this scoping review is to create an overview of the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

This review was conducted following the expanded PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2021 guidelines for scoping reviews (O’Dea et al. 2021) with the purpose to identify moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was conducted according to the Arksey and O’Malley six-step methodological framework (Arksey and O’Malley 2005).

The methodological model includes the following steps:

- (1)

- Identifying a research question;

- (2)

- Identifying relevant studies;

- (3)

- Selecting a study;

- (4)

- Charting data;

- (5)

- Collating, summarizing, and reporting results;

- (6)

- Optional stage, consultation exercise (optional) (Arksey and O’Malley 2005).

2.2. Identifying the Research Question

To investigate the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, five research questions were formulated:

- (1)

- What is the level of moral distress for HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- (2)

- What risk factors are associated with the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- (3)

- What moral and ethical dilemmas did HCWs face during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- (4)

- What is a research-identified harm caused by moral distress to HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- (5)

- What intervention methods were used to reduce moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic?

2.3. Identifying Relevant Studies

Three researchers designed the search strategy for the study. Keywords were searched in two database systems: PubMed and ProQuest. The selection of studies was carried out by two researchers, independently of each other. Initially, a pilot search was conducted to identify keywords from abstracts and article titles that were considered relevant to the selected topic. The results obtained by the two researchers were reviewed in an open discussion for consistency. The third researcher performed the analysis, synthesis, and description of the obtained data results. All disagreements and misunderstandings were resolved through discussion, reaching a common vision.

To define and develop a search strategy, the following keywords of relevant articles and MeSH terms were used: COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; moral distress; ethical dilemma; ethical challenges; ethical climate; ethical stress; bioethics; psychological stress; life stress; physicians; health care professionals; health care workers; health personnel; nurses; medical staff; nursing staff. Keywords were searched by medical subject (MeSH) and as a major topic; as a text word; as a keyword in the title, abstract, and among keywords; and in all fields. Boolean operators were used: AND/OR, to connect keywords; symbol * was used to abbreviate the word. The search was limited to the following filters: English, full text, free full text; peer review.

The search was carried out from 1 February 2023 till 28 February 2023 in databases: MEDLINE via PubMed, Science Direct; Scopus; on the ProQuest platform (all databases), and the Cochrane Library. The above-mentioned database systems were chosen because they best represented literature and research works relating to the HCWs’ psychology and social sciences. They contained interdisciplinary studies as well as full-text versions. Studies published before December 2019 were excluded, as the aim of this scoping review was to identify studies on the given topic focusing on the assessment of moral distress since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. View Supplementary Materials: Table S1. Research strategies.

2.4. Selecting a Study

At the beginning of the selection process, inclusion/exclusion criteria were clearly defined, according to which relevant studies were selected (the data are shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Compliance criteria of scientific publications.

One of the researchers exported the obtained search results to the EndNote reference management tool with the purpose to manage a screening process as well as exclude duplicates. Further, two independent researchers screened the selected articles by titles and abstracts according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

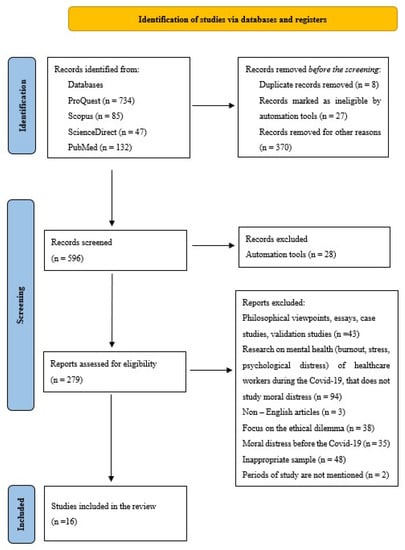

In the first stage of research identification, 1001 articles complying with the proposed keywords were found. Two independent librarians performed an initial, manual selection of studies from the articles (n = 596) that remained after the screening. Titles and summaries of selected studies were reviewed along with their compliance with predefined criteria: COVID-19 pandemic, moral distress, and healthcare workers. As a result, articles that did not mention moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic were excluded (n = 289). The automation tool, in its turn, excluded additional articles (n = 28).

Figure 1 illustrates the process of identifying and selecting articles included in the scoping review.

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram of the search and selection process, based on the PRISMA flowchart.

Full texts were searched for the selected articles (n = 279). After studying in depth, the content, the third researcher performed a secondary selection according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text articles were classified into two categories: “comply” or “does not comply”. After checking full texts, the following articles were excluded according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) philosophical viewpoints, essays, case studies, and validation studies (n = 43); (2) articles that studied aspects of HCWs’ mental health such as burnout, stress, and psychological distress, but not those that examined moral distress (n = 94); (3) articles that were not in English (n = 3); (4) studies that primarily focused on ethical dilemmas (n = 38); (5) moral distress before the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 35); (6) inappropriate study sample (n = 48); (7) the period of study conduct was not mentioned in the article (n = 2). As a result, according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria (n = 16), articles were included in the scoping review.

2.5. Charting Data

The research team jointly developed a data synthesis table. Characteristics of the basic research were tabulated. Analyzing full texts, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the scoping review, the following data were obtained:

- Author, Year, Title—To Identify that a Relevant Study Examines the Moral Distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Time of Measurement—A Study Shall Be Conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Country—To Identify the Country Where the Study Was Conducted

- Research Aim—The Selected Studies Shall Research Moral Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Research Methods—Qualitative, Quantitative, Or Mixed Design Study

- Theoretical Context—To Identify a Theory Within Which the Phenomenon of Moral Distress Is Being Defined

- Subjects—To Identify that a Research Sample Consists of HCWs and to Characterize It, e.g., Size of the Sample, Gender, and Profession

- Study Size—To Identify the Number of HCWs—Practitioners Who Were Included in the Study

- Measures—To Identify a Survey Used for Measuring Moral Distress

- Data Collection—To Identify How Surveys Were Distributed

- Data Analysis—To Identify Statistical Methods Applied in the Studies

- Main Results—To Summarize the Main Results Obtained in the Research on the Moral Distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

According to Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey and O’Malley 2005), this stage involved synthesizing the data obtained, reporting results, and applying meaning to the results. To identify the main themes relating to the moral distress of HCWs during COVID-19, according to Peters et al. (2020), qualitative data coding for the obtained results was performed. The obtained data were exported to a Word spreadsheet, and the qualitative data content analysis method was applied (Elo and Kyngäs 2008). Themes were formed within each of the code groups by combining common codes and grouping them by meaning at a later stage.

3. Results

Most of the included studies (n = 9) were conducted in 2022 (Asadi et al. 2022; Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Gherman et al. 2022; Hegarty et al. 2022; Kiziltepe and Kurtgöz 2022; Maffoni et al. 2022; Lemmo et al. 2022), accounting for 56% of the included studies. On the other hand, five articles (n = 5) were published in 2021 (Smallwood et al. 2021; Donkers et al. 2021; Patterson et al. 2021; Hines et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021), and they account for 31% of the included studies. For 2023, two studies (n = 2) were identified (Kok et al. 2023; Koonce and Hyrkas 2023), representing 13% of the included studies. The studies were conducted from December 2019 (Kok et al. 2023) till February 2022 (Gherman et al. 2022).

The country distribution of the 16 included studies was as follows: Netherlands (n = 2), USA (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), Iran (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), United States (n = 1), Finland (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Romania (n = 1), England (n = 1), and Turkey (n = 1).

The research methods used in the studies were as follows: quantitative design studies (n = 8) (Asadi et al. 2022; Smallwood et al. 2021; Donkers et al. 2021; Hines et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022; Gherman et al. 2022; Maffoni et al. 2022; Kok et al. 2023) and qualitative design studies (n = 8) (Patterson et al. 2021; Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Hegarty et al. 2022; Kiziltepe and Kurtgöz 2022; Koonce and Hyrkas 2023; Lemmo et al. 2022; Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022).

The following theoretical frameworks were used: in one research work, Hamric (n = 1) (Asadi et al. 2022); Jameton (n = 7) (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Kok et al. 2023; Donkers et al. 2021; Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Kiziltepe and Kurtgöz 2022; Maffoni et al. 2022; Lemmo et al. 2022); Epstein (n = 1) (Smallwood et al. 2021); Corley (n = 2) (Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Hines et al. 2021); Morley (n = 1) (Koonce and Hyrkas 2023); and in four cases (n = 4), the theoretical framework of the study was not mentioned (Patterson et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021; Gherman et al. 2022; Hegarty et al. 2022).

The selection of the included articles was made by nurses (n = 4) (Asadi et al. 2022; Gherman et al. 2022; Koonce and Hyrkas 2023; Lemmo et al. 2022), doctors (n = 2) (Patterson et al. 2021; Kiziltepe and Kurtgöz 2022) and HCWs in general (n = 10) (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Kok et al. 2023; Smallwood et al. 2021; Donkers et al. 2021; Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Hines et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021; Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Hegarty et al. 2022; Maffoni et al. 2022).

The sample of the quantitative studies ranged from 135 to 7846 respondents, while the sample of the qualitative studies ranged from 8 to 42 participants.

The articles included in the scoping review focused on the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In total, five all-embracing themes characterizing the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified:

- Level of moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Risk factors of moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Moral and ethical dilemmas during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Harm to HCWs caused by moral distress;

- Intervention methods to reduce moral distress.

3.1. Level of Moral Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Different levels of moral distress were found among health care workers.

A study conducted by Donkers et al. showed that the moral distress level among nurses was higher than that among the support staff (Donkers et al. 2021). In its turn, the results of the research carried out in Iran showed that the moral distress level of nurses was low (Asadi et al. 2022). Performing in-depth analysis and dividing respondents by their marital status helped the researchers to find out that the moral distress level was higher among unmarried employees. The results of the study clearly showed that marital status served as one of the promoters of moral distress, thus influencing the level of the latter. Those who were not married experienced higher moral distress (Asadi et al. 2022). In their turn, the Kok et al. research results showed no significant difference in moral distress levels between doctors and nurses (Kok et al. 2023). A study conducted in Israel showed high levels of moral distress (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022), confirming the mental health problems of HCWs. Active monitoring of mental health is required.

3.2. Risk Factors of Moral Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Risk factors for moral distress related to ethical dilemmas, lack of resources, and actions that did not correspond to the moral values of healthcare workers.

HCWs reported that they experienced moral distress due to a variety of reasons, including unpredictable and extreme changes, which had a very significant impact on the ability of HCWs to serve patients and provide quality healthcare services (Fagerdahl et al. 2022). They failed to provide patient-oriented, empathetic care. HCWs faced various moral and ethical dilemmas while following the established pandemic management protocols (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022). Another reason was the risk of infection. HCWs were afraid of infecting their families and people close to them (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). HCWs also reported moral distress relating to a lack of resources (58.3%); wearing personal protective equipment (31.7%), which limited their ability to care for patients; family exclusion, which contradicted their values (60.2%); and the fear of deceiving colleagues if they were infected and had to quarantine (55.0%) (Smallwood et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). Hard work, where their actions did not correspond to their moral values, was also noted (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021; Hegarty et al. 2022). A study conducted in Iran showed a significant correlation between moral distress and marital status (p = 0.001) and rotation among posts (p = 0.01). Nurses whose workplaces practiced staff rotation among posts experienced greater moral distress (Asadi et al. 2022). The obtained results allowed us to conclude that working in a changing professional work environment might contribute to the development of moral distress of HCWs. A study conducted in the United States showed that moral distress was caused by moral and ethical dilemmas, pervasive uncertainty, unclear duties, isolation, burnout, fear for personal safety and health, risk of infecting family and friends, financial concerns, self-doubt, and dissatisfaction with an acutely introduced telehealth system (Patterson et al. 2021). The results of Ahokas and Hemberg’s qualitative study identified several risk factors causing moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of them was a lack of time. HCWs were forced to prioritize between groups of patients and choose which patient to devote more time to. It caused massive moral distress among HCWs. The COVID-19 pandemic served as an even greater reason for time shortages, which accordingly increased the moral distress of HCWs and affected the quality of patient care (Ahokas and Hemberg 2022). A lack of resources was mentioned by HCWs as the next risk factor. HCWs pointed out that one of the biggest resource deficiencies related to a qualified staff, which would facilitate the sharing of responsibilities and a reduction in morale distress (Hegarty et al. 2022). HCWs’ ability to emphasize ethical values was limited because economic factors were the most important (Ahokas and Hemberg 2022). A study conducted in Israel identified the inability to provide reasonable health care due to a lack of time, which simultaneously imposed a feeling of responsibility for patients’ sufferings or loss of life, as one of the risks (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022). In their turn, Lemmo et al. identified the following risk factors for moral distress: moral constraints, tension, conflict, dilemmas, moral uncertainty, and moral compromise (Lemmo et al. 2022).

3.3. Moral and Ethical Dilemmas during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The moral and ethical dilemmas experienced by healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic related to the personal moral values of the workers and external constraints.

Ethical dilemmas experienced by healthcare workers related to a lack of resources. In practice, it was manifested as an insufficient number of beds in the COVID-19 wards and intensive care units, as well as a lack of HCWs. Institutions with fewer employees began to lose more labor force, and the level of absence due to sick leave increased as well. Infected HCWs were isolated. The remaining ones had to work with incompetent colleagues, take care of an inadequately large number of patients, face a lack of communication with managers, and deal with vaguely defined regulations and guidelines that were changing daily (Donkers et al. 2021). Very often, regular changes in guidelines created situations where HCWs had to make urgent moral and ethical decisions (Hegarty et al. 2022). A lack of medication and the impossibility to confront other HCWs and move freely and fast in emergencies made the staff feel constrained, as they were unable to properly provide care. Nurses noted that they experienced situations where they felt unable to do the right thing or were unable to prevent actions that were considered morally wrong due to institutional, contextual, or personal barriers (Lemmo et al. 2022). HCWs were often forced to act beyond their competence, leading some of them to believe that they had put patients at risk due to inadequate infection control procedures (Lemmo et al. 2022). HWCs felt angry with the government for mismanaging the COVID-19 guidelines and underfunding services. Employees were tasked to compensate for systemic errors by working excessive amounts of overtime. This led to cynicism towards organizational attempts to address staff well-being and was seen as a failure to deal with the root cause of the problem and did not reduce the moral distress caused (Hegarty et al. 2022). HCWs experienced feelings of guilt when they felt personally responsible for not meeting society’s expectations, which mainly related to failings in the provision of patient-oriented health care. HCWs expressed a certain degree of guilt regarding their involvement. They felt like accomplices in the system’s failures because they were not adequately trained in how to deal with a situation of the mass epidemic to satisfy public needs and provide high-quality care (Hegarty et al. 2022).

Insufficient clinical knowledge in working during the COVID-19 pandemic served as another cause of moral and ethical dilemmas. HCWs had to experience situations where they felt unprepared and incompetent while dealing with the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. For this reason, HCWs lost many patients in a very short period. The consequences of the virus manifested differently from patient to patient, so a different treatment, which had not been tested until then, was needed. HCWs had to experience new moral and ethical situations. Performing work duties in conditions of the pandemic massively contributed to the development of moral distress among HCWs (Lemmo et al. 2022). It served as both internal and external factors of ethical dilemmas.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, all HCWs were obliged to use personal protective equipment. Working in special protective clothing prevented emotional contact between HCWs and patients. Infected patients were isolated. Any visits to hospitalized patients were prohibited. HCWs had to forbid visits from relatives. Ward staff experienced moral and ethical situations where they were unable to facilitate communication between dying patients and their family members or to support patients to die in a dignified manner because there were too many patients requiring attention (Hegarty et al. 2022). The above-mentioned aspects represent another situation of ethical dilemmas experienced by healthcare workers.

3.4. Harm to HCWs Caused by Moral Distress

The harm of moral distress experienced by healthcare workers related to the deterioration of mental health, psychosocial problems, and burnout.

Looking at the effects of moral distress on healthcare workers, problems such as increased stress, anxiety, and irritability were noted. Many HCWs marked a sense of helplessness, as well as a difficulty in falling asleep and a lower quality of sleep (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). HCWs reported that the moral distress they experienced either increased or decreased their ability to empathize with others. Both the increased and decreased ability to empathize were interpreted in a negative light (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022). Such psychosocial health problems as exhaustion and sleep disorders were also mentioned (Donkers et al. 2021). One of the studies showed a positive correlation between moral distress and psychosomatics and concerns about the risk of being infected (Maffoni et al. 2022). Moral distress caused difficulties for employees at both individual and organizational levels, where moral distress was associated with increased levels of anxiety, depression, and risk of burnout (Smallwood et al. 2021; Donkers et al. 2021). The study conducted by Kok et al. proved that moral distress was associated with burnout, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization in 22.7% of cases (Kok et al. 2023). The obtained results showed a positive correlation between moral distress and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, as well as increased emotional exhaustion, which hurt the relatives of HCWs (Kok et al. 2023). In its turn, the study conducted in England showed a negative effect of moral distress on the mental health of HCWs. Deterioration in mental health was associated with accumulated moral distress at work, exacerbated by life stressors. Most often, moral distress manifested as increased anxiety, which caused sleep disorders for several people. Anxiety was observed in several employees who used stress-related sick leave. One of the HCWs suffered from panic attacks during night shifts, which disappeared when she left her job (Hegarty et al. 2022). Moral distress of HCWs was associated with a deterioration of mental health that was further aggravated by constant stressors.

A study conducted in Italy identified six moral distress detriments that HCWs suffered from. Employees experienced a sense of powerlessness, a lack of resources, and an inability to change the course of events determined by the spread of infection. Feelings of undervaluation were present when employees were unable to express their professional opinion about the treatment process. A great sense of uncertainty and confusion contributed to the difficulty in discussing decisions that seemed extremely important to HCWs (Lemmo et al. 2022). In some cases, nurses felt angry when decisions made by doctors contradicted their opinion. Moreover, such anger was described as a reaction to doctors who seemingly did not consider nurses’ opinions. The sadness experienced related to a need for making choices between patients to be treated and those to be allowed to die. The feeling of guilt, in its turn, occurred in situations of moral uncertainty. The feeling of helplessness was created by situations where HCWs felt completely helpless facing death (Lemmo et al. 2022). All the above-mentioned permeated the moral realm, causing HCWs to face stress, burnout, and moral discomfort.

3.5. Intervention Methods to Reduce Moral Distress

Informal resources, such as self-care resources and support from colleagues, family members, or friends, were the most frequently cited ways of reducing moral distress, followed by professional or formal sources of support, such as discussions with supervisors or the use of counselling support (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). Very often, HCWs used counselling offered by psychologists, the help of social workers, pastoral counselling, and the support of other members of the mental health support team. In addition, an “open” culture where managers were welcoming was mentioned. Employees had an opportunity to share questions, feelings, and emotions of a professional nature, as well as an opportunity to discuss and dispute harm caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, human mortality, and moral distress experienced (Donkers et al. 2021; Ahokas and Hemberg 2022). Also, a study carried out by Kok et al. proved that support from immediate supervisors reduced moral distress and emotional exhaustion (Kok et al. 2023). Regular monitoring of employees’ well-being was also considered important. Talking to experts, colleagues, or a therapist helped prevent the adverse effects of moral distress on the mental health of HCWs (Ahokas and Hemberg 2022). Facing emergencies in the healthcare sector, for instance, a pandemic, it was important to draft a professional and organizational support plan in due time. Such action helped strengthen both the internal and external resources of HCWs. It helped to avoid emotional burnout (Gustavsson et al. 2020). Several HCWs noted that ability to express feelings of anger, guilt, and frustration openly was important to reduce moral distress. It helped to normalize their level of moral distress. Others used “black humor” (Hegarty et al. 2022). Those who did not have an opportunity for clinical supervision attended reflective practice groups. Sometimes, line managers, providing reassurance and support, fill in this role. Engaging in activities outside work such as physical exercise, cooking, reading, meditation, spending time with family, etc., was helpful. These activities provided a temporary escape from difficult thoughts and helped to separate work and private lives (Hegarty et al. 2022; Klitzman 2022).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to create an overview of the moral distress of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the level of moral distress, risk factors, ethical dilemmas, harms caused, and intervention methods used to reduce moral distress were considered.

Healthcare facilities were a place where care providers were exposed to psycho-emotional experiences, patients’ sufferings, possible unsuccessful care results, and moral distress daily (Friganović et al. 2019). Endless shifts that were difficult to match with the natural circadian rhythm (Shanafelt et al. 2020), concerns about the effectiveness of the personal protective equipment, and widespread fear of being infected and thereby infecting a family played a crucial role in facilitating moral distress (Bettinsoli et al. 2020; Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs had to face different types of risks, including saving the lives of countless patients, a lack of resources (Liberati et al. 2009; Sun et al. 2020; Williamson et al. 2020), performing professional duties while experiencing moral and ethical dilemmas (Maunder et al. 2003), and a fear of being infected (Silverman et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2022; Lake et al. 2022; Walton et al. 2020). This emotionally and physically difficult situation forced me to focus seriously on HCWs’ mental health and well-being. Moral distress among HCWs became one of the most researched topics about the effects of the pandemic on HCWs’ mental health (Asadi et al. 2022; Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Kok et al. 2023; Smallwood et al. 2021; Donkers et al. 2021; Patterson et al. 2021; Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Donkers et al. 2021; Hines et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021; Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Gherman et al. 2022; Hegarty et al. 2022; Kiziltepe and Kurtgöz 2022; Koonce and Hyrkas 2023; Maffoni et al. 2022; Lemmo et al. 2022).

Most studies focused on investigating risk factors of moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unpredictable and extreme changes were the most common risk factors (Fagerdahl et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022), and apparently, HCWs were not properly trained to face them. Similar results were also shown in previous studies of moral distress (Sriharan et al. 2021; Riedel et al. 2022; Smallwood et al. 2021; Lamiani et al. 2021), which demonstrated that HCWs’ moral distress significantly increased when the healthcare system faced a crisis and had to implement pandemic management protocols. HCWs noted the pressure they experienced in situations when the triage of patients had to be made. Public health and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic were considered more important than the health and safety of HCWs themselves, which created additional feelings of vulnerability, powerlessness, and overload (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022). Performing work under such crisis conditions failed to provide patient-oriented, empathetic care (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022). A huge lack of resources and personal protective equipment was observed (Smallwood et al. 2021; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). Other studies also showed these risk factors as crucial for moral distress (Miljeteig et al. 2021; Kreh et al. 2021; Billings et al. 2021; Lake et al. 2022), including the ones relating to the constant change in a work team, because of the rotation to different positions in the department or even to other departments (Asadi et al. 2022), moral and ethical dilemmas, the introduction of a telehealth system (Patterson et al. 2021; Lemmo et al. 2022), and a lack of time (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the introduction of telehealth systems to facilitate communication. At the same time, technologies introduced acted as a barrier to establishing an empathic connection between HCWs and patients and their family members. It was especially felt in situations where sensitive topics such as the diagnosis of COVID-19, treatment options, healthcare resource limitations, and decisions about dying with dignity were discussed (Bowman et al. 2020; Lau et al. 2020). An opportunity to provide patient- and family-oriented communication was prohibited, which, in turn, created a sense of moral distress among HCWs. Performing professional activities in extreme conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic fostered the development of moral distress among HCWs at individual, organizational, and social levels (Epstein et al. 2019; Jameton 1993).

Daily stressors that were not faced very often and not continuously caused moderate psycho-social consequences. In these cases, moral distress had no long-term effect on the level of functioning (Litz et al. 2009). Jameton interpreted it as an effect of short-term stress on the development of moral distress (Jameton 1993). Experiencing moral distress in professional work was a relative norm that was also proved by the results of the scoping review, where the results of the Iranian study showed low levels of moral distress in performing one’s job duties during the COVID-19 pandemic (Asadi et al. 2022). In their turn, the results of another study showed that there was no significant difference in the level of moral distress between doctors and nurses (Kok et al. 2023), and this fact was also acknowledged by other authors (Miljeteig et al. 2021; Norman et al. 2021; Lake et al. 2022). However, many HCWs faced continuous moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this was proved by the results of the Israeli research study showing high levels of moral distress (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2022). Other countries also faced similar experiences (Norman et al. 2021; Wilson et al. 2022). It could be explained by experiencing cumulative stress situations. Moral distress increased, and a person’s overall moral integrity decreased, facing constant stressors (Litz et al. 2009; Epstein et al. 2019).

Analyzing obtained results regarding the consequences of moral distress, HCWs most often mentioned increased levels of stress, anxiety, and irritability (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). Also, the results of Zerach’s research work showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome among HCWs (Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021), including various psycho-social health problems, such as fatigue and sleep disorders (Donkers et al. 2021), difficulties with individual and organizational levels, where moral distress led to increased depression and burnout (Smallwood et al. 2021; Donkers et al. 2021), emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Kok et al. 2023), feeling of helplessness (Lemmo et al. 2022), anger and sadness (Hegarty et al. 2022). Several studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that problems of emotional exhaustion and burnout faced by HCWs were among the most frequent symptoms of post-traumatic stress (Wang et al. 2020; Mantri et al. 2020; Wilson et al. 2022). In a longitudinal study by Wilson, burnout was identified as a contributing factor to moral distress (Wilson et al. 2022). It showed that HCWs who already had psychological problems were much more vulnerable to the development of moral distress. HCWs’ experiences differed in individual well-being and mental health and at the organizational level. Emotional and physical exhaustion (Kreh et al. 2021), burn-out (Wang et al. 2020; Mantri et al. 2020; Wilson et al. 2022), and willingness to quit (Patterson et al. 2021) appeared in the social context of work.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs were permanently forced to deal with moral and ethical dilemmas relating to a lack of organizational and human resources, a high level of absence due to sick leave, the isolation of infected HCWs, a large number of patients, a lack of communication with managers, and vaguely defined regulations and guidelines changing on daily basis (Hegarty et al. 2022; Donkers et al. 2021). HCWs had to work with unprepared colleagues. Insufficient training led to situations where HCWs lost many patients in a very short time (Lemmo et al. 2022). Risk factors of moral distress at the interpersonal level, caused by a lack of competence of colleagues, became urgent (Silverman et al. 2021; Norman et al. 2021; Billings et al. 2021). A shortage of medication also had to be faced (Lemmo et al. 2022). Moral and ethical dilemmas were associated with the isolation of infected patients. Medical personnel had to prohibit visits from relatives, which made difficult the communication with family members of deceased patients. Patients were deprived of the opportunity to die in a dignified way because too many of them needed urgent help (Hegarty et al. 2022; Donkers et al. 2021). Studies conducted in other countries also showed that the rights of relatives to visit and care for dying patients were restricted during the COVID-19 pandemic (Silverman et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2021; Lake et al. 2022).

The obtained results indicate that healthcare organizations should seriously consider introducing multifaceted training programs. There is a need to educate HCWs about action plans in case of ethical dilemmas and how to apply these skills in clinical practice. Stress caused by moral and ethical dilemmas seriously affects the mental health of HCWs.

Healthcare institutions shall develop preventive measures promptly for employees who need psychological support in self-regulation and overcoming moral stress.

The obtained results showed that employees used informal resources or self-care to reduce moral distress. Sometimes, it was some advice from colleagues, support from family members or friends, professional or formal support, discussions with managers, or the use of consultative support (Alonso-Prieto et al. 2022; Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021). The obtained results are consistent with the previous study, where the help of colleagues and managers was emphasized as one of the most relevant support mechanisms in overcoming moral distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Mills and Cortezzo 2020). Counseling offered by psychologists, the assistance of social workers, support of pastoral counsellors, and other members of the mental health support team were used. Organizations practiced an “open” culture. Employees were allowed to ask questions, share feelings and emotions, and discuss losses, human mortality, and moral distress experienced (Donkers et al. 2021; Ahokas and Hemberg 2022). Other organizations, in their turn, paid a lot of attention to regularly monitoring employees’ well-being, including providing the opportunity to talk to experts, colleagues, or a therapist (Ahokas and Hemberg 2022; Hines et al. 2021). A professional and organizational support plan was created that helped to strengthen both internal and external individual resources, reduce moral distress, and avoid burnout (Gustavsson et al. 2020). Others enjoyed “black humor” (Hegarty et al. 2022). Engaging in activities outside work, i.e., physical exercising, cooking, reading, meditation, and spending time with family, were helpful (Hegarty et al. 2022; Klitzman 2022).

Alleviating moral distress helps an individual to restore moral freedom of action and autonomy. Therefore, it is crucial to develop employees’ self-regulation skills. A goal of reducing moral distress is not to create self-contentment or tolerance towards unethical clinical practice. The aim is to recognize these stress-causing triggers and apply self-regulation skills to reduce short- and long-term harmful effects of the former on the mental health of HCWs (Rushton 2018). Thus, a reduction in moral distress is achieved, which, in turn, results in the reduction in burnout, depression, and secondary post-traumatic stress (Azoulay et al. 2020).

The mental and physical health of HCWs in epidemiological conditions is an essential criterion for patients’ safety and the effective provision of health care services. Identifying moral distress and its consequences will contribute to the development of the moral resilience of HCWs at healthcare organizations. The obtained results will improve the understanding of society, organizations, and researchers on the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. It will serve as a basis for the development of different strategies in similar epidemic crises.

4.1. Strengths

One of the strengths of the scoping review is the wide range of study designs included. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research designs were revised, allowing the widest possible examination of the factors causing moral distress to HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. This scoping review included different groups of HCWs, thus revealing more information on the experience of moral distress in different specialties. Five database systems were searched. Investigator triangulation was applied to ensure the reliability and validity of the obtained data.

4.2. Constraints

This scoping review has several constraints: no quality assessment of the included studies was performed, as this is not a mandatory requirement for conducting a scoping review. A scoping review carried out in this way does not assess the quality of the obtained research results. The search strategy was limited to the English language filter, as the researchers of the given scoping review were only proficient in English. Research in other languages would be able to expand the quantity and quality of the information obtained. Methodological articles, conference abstracts, proceedings, reviews, or discussions were not included. One study was conducted as a longitudinal study, which would allow a broader discussion of the causal relationships of moral distress (Hines et al. 2021).

4.3. Future Directions

Results of this scoping review indicate that further research is needed to identify and explore risk factors of moral distress, as well as moral detriments and coping strategies for the former. Considering individual characteristics and organizational support rendered to HCWs is crucial when planning future studies of the moral distress of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. That, in turn, would help develop a plan of preventive measures to better deal with situations that cause increased moral distress in the workplace and significantly affect the quality of healthcare. In addition, it is necessary to pay increased attention to research relating to the studies of HCWs’ mental health in various crises in the health sector. That would allow healthcare organizations to develop action strategies and algorithms that, in turn, will reduce the negative consequences of moral distress on the mental health of HCWs.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review looked at the moral stressors of HCW during COVID-19. The spread of the pandemic added a host of new risk factors to the many responsibilities of healthcare workers, turning a health emergency into a full-blown mental health emergency. A lack of resources, unclear guidelines, communication difficulties, working with untrained colleagues, and the performance of duties beyond the limits of competence strongly contributed to the development of moral distress among HCWs. Every day, HCWs had to live with feelings of guilt and shame for not being able to save enough lives (Rushton et al. 2013; Williamson et al. 2020; Greenberg et al. 2020; French et al. 2022). These experiences created new, morally traumatic mental health disorders for HCWs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci12070371/s1, Table S1: Research strategies; Table S2: Scoping review results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N. and S.Š.; methodology, E.N. and S.Š.; software, E.N.; validation, E.N., S.Š. and I.G.; formal analysis, S.Š.; investigation, E.N. and S.Š.; resources, E.N.; data curation, S.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, E.N.; writing—review and editing, S.Š. and I.G.; visualization, E.N.; supervision, S.Š. and I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Due to the theoretical nature of this study, ethical review and approval were waived as no humans or animals were involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| MD | moral distress |

| HCWs | healthcare workers |

References

- Ahokas, Fanny, and Jessica Hemberg. 2022. Moral Distress Experienced by Care Leaders’ in Older Adult Care: A Qualitative Study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Prieto, Esther, Holly Longstaff, Agnes Black, and Alice Karin Virani. 2022. COVID-19 Outbreak: Understanding Moral-Distress Experiences Faced by Healthcare Workers in British Columbia, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 9701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, Neda, Fatemeh Salmani, Narges Asgari, and Mahin Salmani. 2022. Alarm Fatigue and Moral Distress in Icu Nurses in COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Nursing 21: 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azoulay, Elie, Jan De Waele, Ricard Ferrer, Thomas Staudinger, Marta Borkowska, Pedro Povoa, and Katerina Iliopoulou. 2020. Symptoms of Burnout in Intensive Care Unit Specialists Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak. Annals of Intensive Care 10: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinsoli, Maria Laura, Daniela Di Riso, Jaime Lee Napier, Lorenzo Moretti, Pierfrancesco Bettinsoli, Michelangelo Delmedico, Andrea Piazzolla, and Biagio Moretti. 2020. Mental Health Conditions of Italian Healthcare Professionals During the COVID-19 Disease Outbreak. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 12: 1054–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, Jo, Camilla Biggs, Brian Chi Fung Ching, Vasiliki Gkofa, David Singleton, Michael Bloomfield, and Talya Greene. 2021. Experiences of Mental Health Professionals Supporting Front-Line Health and Social Care Workers During COVID-19: Qualitative Study. BJPsych Open 7: e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Brynn A., Anthony L. Back, Andrew Esch, and Nadine Marshall. 2020. Crisis Symptom Management and Patient Communication Protocols Are Important Tools for All Clinicians Responding to COVID-19. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60: e98–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, Domenico, and Maurizio Vanelli. 2020. Who Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 91: 157–60. [Google Scholar]

- Donkers, Moniek, Vincent Gilissen, Math Candel, Nathalie van Dijk, Hans Kling, Ruth Heijnen-Panis, and Elien Pragt. 2021. Moral Distress and Ethical Climate in Intensive Care Medicine During COVID-19: A Nationwide Study. BMC Medical Ethics 22: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzinski, Denise, Benjamin Hoisington, and Crystal Brown. 2020. Ethics Lessons from Seattle’s Early Experience with COVID-19. The American Journal of Bioethics 20: 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, Elizabeth, Phyllis Whitehead, Chuleeporn Prompahakul, Leroy Thacker, and Ann Baile Hamric. 2019. Enhancing Understanding of Moral Distress: The Measure of Moral Distress for Health Care Professionals. AJOB Empirical Bioethics 10: 113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, Andre, Anuprit Kale, Romain Paulus, Kazuma Hashimoto, Wenpeng Yin, Dragomir Radev, and Richard Socher. 2021. COVID-19 Information Retrieval with Deep-Learning Based Semantic Search, Question Answering, and Abstractive Summarization. NPJ Digital Medicine 4: 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerdahl, Ann-Mari, Eva Torbjörnsson, Martina Gustavsson, and Andreas Älgå. 2022. Moral Distress among Operating Room Personnel During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Surgical Research 273: 110–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, Colleen, and Bradley Hayward. 2022. Ethical dilemmas, moral distress, and the risk of moral injury: Experiences of residents and fellows during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Academic Medicine 97: S55–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, Lorna, Paul Hanna, and Catherine Huckle. 2022. “If I Die, They Do Not Care”: Uk National Health Service Staff Experiences of Betrayal-Based Moral Injury During COVID-19. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 14: 516–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friganović, Adriano, Polona Selič, and Boris Ilić. 2019. Stress and Burnout Syndrome and Their Associations with Coping and Job Satisfaction in Critical Care Nurses: A Literature Review. Psychiatria Danubina 31: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gherman, Mihaela Alexandra, Laura Arhiri, Andrei Corneliu Holman, and Camelia Soponaru. 2022. The Moral Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Nurses’ Burnout, Work Satisfaction and Adaptive Work Performance: The Role of Autobiographical Memories of Potentially Morally Injurious Events and Basic Psychological Needs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, Neil, Mary Docherty, Sam Gnanapragasam, and Simon Wessely. 2020. Managing Mental Health Challenges Faced by Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic. BMJ 368: m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, Martina E., Filip K. Arnberg, Niklas Juth, and Johan von Schreeb. 2020. Moral Distress among Disaster Responders: What Is It? Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 35: 212–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, Siobhan, Danielle Lamb, Sharon Stevelink, Rupa Bhundia, Rosalind Raine, Mary Jane Doherty, and Hannah Scott. 2022. ‘It Hurts Your Heart’: Frontline Healthcare Worker Experiences of Moral Injury During the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 13: 2128028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, Stella, Katherine Chin, Danielle Glick, and Emerson Wickwire. 2021. Trends in Moral Injury, Distress, and Resilience Factors among Healthcare Workers at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameton, Andrew. 1984. Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Jameton, Andrew. 1993. Dilemmas of Moral Distress: Moral Responsibility and Nursing Practice. AWHONN’s Clinical Issues in Perinatal and Women’s Health Nursing 4: 542–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Lisa, and Irena Burić. 2020. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Burnout: Determining the Directions of Prediction through an Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Panel Model. Journal of Educational Psychology 112: 1661–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziltepe, Selin Keskin, and Asli Kurtgöz. 2022. Understanding Physicians’ Moral Distress in the COVID 19 Pandemic. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine 39: 958–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klitzman, Robert. 2022. Needs to address clinicians’ moral distress in treating unvaccinated COVID-19 patients. BMC Medical Ethics 23: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Niek, Jelle Van Gurp, Johannes van der Hoeven, Malaika Fuchs, Cornelia Hoedemaekers, and Marieke Zegers. 2023. Complex Interplay between Moral Distress and Other Risk Factors of Burnout in Icu Professionals: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Survey Study. BMJ Quality & Safety 32: 225–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koonce, Myrna, and Kristiina Hyrkas. 2023. Moral Distress and Spiritual/Religious Orientation: Moral Agency, Norms and Resilience. Nursing Ethics 30: 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreh, Alexander, Rachele Brancaleoni, Sabina Chiara Magalini, Daniela Pia Rosaria Chieffo, Barbara Flad, Nils Ellebrecht, and Barbara Juen. 2021. Ethical and Psychosocial Considerations for Hospital Personnel in the COVID-19 Crisis: Moral Injury and Resilience. PLoS ONE 16: e0249609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, Eileen, Aliza Narva, Sara Holland, Jessica Smith, Emily Cramer, Kathleen Fitzpatrick Rosenbaum, Rachel French, Rebecca Clark, and Jeannette A. Rogowski. 2022. Hospital Nurses’ Moral Distress and Mental Health During COVID-19. Journal of Advanced Nursing 78: 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamiani, Giulia, Davide Biscardi, Elaine C. Meyer, Alberto Giannini, and Elena Vegni. 2021. Moral Distress Trajectories of Physicians 1 Year after the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Grounded Theory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 13367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Siddique, Muhammad Usman, Sanaullah Manzoor, Waleed Iqbal, Junaid Qadir, Gareth Tyson, and Ignacio Castro. 2020. Leveraging Data Science to Combat COVID-19: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 1: 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Jen, Janine Knudsen, Hannah Jackson, Andrew B. Wallach, Michael Bouton, Shaw Natsui, and Christopher Philippou. 2020. Staying Connected in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Telehealth at the Largest Safety-Net System in the United States: A Description of Nyc Health+ Hospitals Telehealth Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Affairs 39: 1437–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmo, Daniela, Roberta Vitale, Carmela Girardi, Roberta Salsano, and Ersilia Auriemma. 2022. Moral Distress Events and Emotional Trajectories in Nursing Narratives During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 8349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, Alessandro, Douglas Altman, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Cynthia Mulrow, Peter Gøtzsche, John Ioannidis, and Mike Clarke. 2009. The Prisma Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 62: e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litz, Brett, Nathan Stein, Eileen Delaney, Leslie Lebowitz, William Nash, Caroline Silva, and Shira Maguen. 2009. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review 29: 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jenny, Anthony Nazarov, Rachel Plouffe, Callista Forchuk, Erisa Deda, Dominic Gargala, and Tri Le. 2021. Exploring the well-being of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Protocol for a prospective longitudinal study. JMIR Research Protocols 10: e32663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Xinhua, Meghana Kakade, Cordelia Fuller, Bin Fan, Yunyun Fang, Junhui Kong, Zhiqiang Guan, and Ping Wu. 2012. Depression after Exposure to Stressful Events: Lessons Learned from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Epidemic. Comprehensive Psychiatry 53: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xinyi, Yingying Xu, Yuanyuan Chen, Chen Chen, Qiwei Wu, Huiwen Xu, Pingting Zhu, and Ericka Waidley. 2022. Ethical Dilemmas Faced by Frontline Support Nurses Fighting COVID-19. Nursing Ethics 29: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Oroz, Miguel, Katherine Hoffmann Pham, Joseph Bullock, Robert Kirkpatrick, Alexandra Luccioni, Sasha Rubel, and Cedric Wachholz. 2020. Artificial Intelligence Cooperation to Support the Global Response to COVID-19. Nature Machine Intelligence 2: 295–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffoni, Marina, Elena Fiabane, Ilaria Setti, Sara Martelli, Caterina Pistarini, and Valentina Sommovigo. 2022. Moral Distress among Frontline Physicians and Nurses in the Early Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 9682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantri, Sneha, Jennifer Mah Lawson, Zhizhong Wang, and Harold Koenig. 2020. Identifying Moral Injury in Healthcare Professionals: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Hp. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2323–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, Robert, Jonathan Hunter, Leslie Vincent, Jocelyn Bennett, Nathalie Peladeau, Molyn Leszcz, and Joel Sadavoy. 2003. The Immediate Psychological and Occupational Impact of the 2003 Sars Outbreak in a Teaching Hospital. CMAJ 168: 1245–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, Joan, and Chris Gastmans. 2015. Moral Distress: A Review of the Argument-Based Nursing Ethics Literature. Nursing Ethics 22: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, Vikas, and Susanta Kumar Padhy. 2020. Ethical dilemmas faced by health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic: Issues, implications and suggestions. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 51: 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljeteig, Ingrid, Ingeborg Forthun, Karl Ove Hufthammer, Inger Elise Engelund, Elisabeth Schanche, Margrethe Schaufel, and Kristine Husøy Onarheim. 2021. Priority-Setting Dilemmas, Moral Distress and Support Experienced by Nurses and Physicians in the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Norway. Nursing Ethics 28: 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Manisha, and DonnaMaria Cortezzo. 2020. Moral Distress in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: What Is It, Why It Happens, and How We Can Address It. Frontiers in Pediatrics 8: 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, Georgina, Jonathan Ives, Caroline Bradbury-Jones, and Fiona Irvine. 2019. What Is ‘Moral Distress’? A Narrative Synthesis of the Literature. Nursing Ethics 26: 646–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Sonya, Jordyn Feingold, Halley Kaye-Kauderer, Carly Kaplan, Alicia Hurtado, Lorig Kachadourian, and Adriana Feder. 2021. Moral Distress in Frontline Healthcare Workers in the Initial Epicenter of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States: Relationship to Ptsd Symptoms, Burnout, and Psychosocial Functioning. Depression and Anxiety 38: 1007–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nyashanu, Mathew, Farai Pfende, and Mandu Ekpenyong. 2020. Exploring the Challenges Faced by Frontline Workers in Health and Social Care Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of Frontline Workers in the English Midlands Region, UK. Journal of Interprofessional Care 34: 655–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, Rose Eleanor, Malgorzata Lagisz, Michael Jennions, Julia Koricheva, Daniel Noble, Timothy Parker, and Jessica Gurevitch. 2021. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology: A Prisma Extension. Biological Reviews 96: 1695–722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oh, Younjae, and Chris Gastmans. 2015. Moral Distress Experienced by Nurses: A Quantitative Literature Review. Nursing Ethics 22: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, Joellen, Todd Edwards, James Griffith, and Sarah Wright. 2021. Moral Distress of Medical Family Therapists and Their Physician Colleagues During the Transition to COVID-19. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 47: 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah, Casey Marnie, Andrea Tricco, Danielle Pollock, Zachary Munn, Lyndsay Alexander, Patricia McInerney, Christina M. Godfrey, and Hanan Khalil. 2020. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18: 2119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrisor, Cristina, Caius Breazu, Madalina Doroftei, Ioana Maries, and Codruta Popescu. 2021. Association of Moral Distress with Anxiety, Depression, and an Intention to Leave among Nurses Working in Intensive Care Units during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 9: 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, Priya-Lena, Alexander Kreh, Vanessa Kulcar, Angela Lieber, and Barbara Juen. 2022. A Scoping Review of Moral Stressors, Moral Distress and Moral Injury in Healthcare Workers During COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, Cynda Hylton. 2018. Moral Resilience: Transforming Moral Suffering in Healthcare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, Cynda Hylton, Alfred Kaszniak, and Joan Halifax. 2013. A Framework for Understanding Moral Distress among Palliative Care Clinicians. Journal of Palliative Medicine 16: 1074–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, Tait, Jonathan Ripp, and Mickey Trockel. 2020. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 323: 2133–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, Henry J., Raya Elfadel Kheirbek, Gyasi Moscou-Jackson, and Jenni Day. 2021. Moral distress in nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. Nursing Ethics 28: 1137–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, Natasha, Amy Pascoe, Leila Karimi, and Karen Willis. 2021. Moral Distress and Perceived Community Views Are Associated with Mental Health Symptoms in Frontline Health Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriharan, Abi, Keri West, Joan Almost, and Aden Hamza. 2021. COVID-19-Related Occupational Burnout and Moral Distress among Nurses: A Rapid Scoping Review. Nursing Leadership 34: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Niuniu, Luoqun Wei, Suling Shi, Dandan Jiao, Runluo Song, Lili Ma, and Hongwei Wang. 2020. A Qualitative Study on the Psychological Experience of Caregivers of COVID-19 Patients. American Journal of Infection Control 48: 592–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, Matthew, Esther Murray, and Michael Christian. 2020. Mental Health Care for Medical Staff and Affiliated Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care 9: 241–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chen, Peter Horby, Frederick Hayden, and George Gao. 2020. A Novel Coronavirus Outbreak of Global Health Concern. The Lancet 395: 470–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, Victoria, Dominic Murphy, and Neil Greenberg. 2020. COVID-19 and Experiences of Moral Injury in Front-Line Key Workers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 317–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Chloe, Hannah Metwally, Smith Heavner, Ann Blair Kennedy, and Thomas Britt. 2022. Chronicling Moral Distress among Healthcare Providers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Analysis of Mental Health Strain, Burnout, and Maladaptive Coping Behaviours. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 31: 111–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Zhe, Lei Shi, Yijin Wang, Jiyuan Zhang, Lei Huang, Chao Zhang, and Shuhong Liu. 2020. Pathological Findings of COVID-19 Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 8: 420–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerach, Gadi, and Yossi Levi-Belz. 2021. Moral Injury and Mental Health Outcomes among Israeli Health and Social Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis Approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 12: 1945749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerach, Gadi, and Yossi Levi-Belz. 2022. Moral injury, PTSD, and complex PTSD among Israeli health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of self-criticism. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 14: 1314–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).