A Decade of Decision Making: Prosecutorial Decision Making in Sexual Assault Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Review of Literature

1.2. “Ideal Victim” Characteristics

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Incident Characteristics

2.2.2. Victim Characteristics

2.2.3. Suspect Characteristics

2.2.4. “Ideal Victim” Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Birvariate Results

3.2. Multivariate Results

3.3. Exploratory Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Policy Implications and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This time frame was based on what the researchers deemed appropriate for their schedules and mental health. Debriefing sessions were held regularly to help combat potential secondary trauma, and the schedule for data collection was flexible to account for mental health needs. |

| 2 | Juvenile reports were not included in this study as they were handled by a different unit. Any case where either the victim or offender was under 17 years of age was considered a juvenile case by this department. Researchers were not granted access to the juvenile unit. |

| 3 | Arrests immediately following the incident were rare. When this occurred, offenders could only be held for 24 h unless official charges were filed. These cases generally involved a third party calling in a disturbance or the victim calling as she was fleeing the scene. This allowed officers to respond almost immediately to the scene of the crime. More commonly, reports were made after the offender had left the scene. Detectives would collect evidence, then present it to the prosecutor with arrest warrants issued after a charging decision was made. |

| 4 | This was labeled “sex” in the record management system. When a transgender individual was a victim, they were coded based on their gender identity, not biological sex. There were less than five instances of this in the full sample of cases. |

| 5 | The record management system in this department counts race as white, black, Asian, or other. Hispanic was captured under “ethnicity”, but this was often left blank. It is possible that the number of Hispanic victims was underestimated due to this not being recorded consistently. The city of the study had a reported Hispanic population of approximately 10%, according to 2021 census estimates. |

| 6 | The database used at this site did not link to convictions but only noted being a suspect or being arrested. Being a suspect was coded here, versus arrest, to better assess informal negative perceptions that law enforcement may hold about individuals in these cases. |

| 7 | Of the victims in this sample, 26.87% (n = 187) had registered addresses outside of the city limits of the department studied. It is likely that these criminal histories are underestimated. For example, if the victim had an extensive criminal history in another jurisdiction, it would not be captured here, and they would be labeled as having “no criminal history”. The victim residing outside of the city limits was not related to victim cooperation or prosecution decisions, likely due to the high presence of victims from neighboring smaller towns. |

| 8 | Initially, non-cooperative victims were usually present in calls made by third parties. |

| 9 | Of the known suspects in this sample, 19.97% (n = 136) had main residences outside of the city limits of the department studied. Therefore, these criminal histories are likely an underestimate. For example, if the suspect had an extensive criminal history in another jurisdiction, it would not be captured here, and they would be labeled as having “no criminal history”. |

| 10 | (1) is an issue only in the creation of the “Ideal Victim” scale, discussed in this section. When the variable is entered into later multivariate analyses individually, (1) indicates the presence of the variable. |

| 11 | Victim cooperation could be discontinued after a prosecutor accepts a case for charges. This post-acceptance disengagement would not be captured here. |

References

- Ahrens, Courtney E. 2006. Being silenced: The impact of negative social reactions on the disclosure of rape. American Journal of Community Psychology 38: 263–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albonetti, Celesta A. 1987. Prosecutorial discretion: The effects of uncertainty. Law and Society Review 29: 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderden, Megan A., and Sarah E. Ullman. 2012. Creating a more complete and current picture: Examining police and prosecutor decision-making when processing sexual assault cases. Violence against Women 18: 525–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, Ronet. 1998. The factors related to rape reporting behavior and arrest: New evidence from the National Crime Victimization Survey. Criminal Justice and Behavior 25: 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beichner, Dawn, and Cassia Spohn. 2005. Prosecutorial charging decisions in sexual assault cases: Examining the impact of specialized prosecution unit. Criminal Justice Policy Review 16: 461–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, Caryl M., Clare McVeigh, Jim McVeigh, Conan Leavey, and Mark A. Bellis. 2008. The involvement of drugs and alcohol in drug-facilitated sexual assault: A systematic review of the evidence. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 9: 178–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryden, David P., and Sonja Lengnick. 1997. Rape in the criminal justice system. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 87: 1194–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch-Amendariz, Noel Bridget, Diana M. Dinetto, Holly Bell, and Thomas Bohman. 2010. Sexual assault perpetrators’ alcohol and drug use: The likelihood of concurrent violence and post-sexual assault outcomes for women victims. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 42: 393–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Bradley A., David S. Lapsey, and William Wells. 2020. An evaluation of Kentucky’s sexual assault investigator training: Results from a randomized three-group experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology 16: 625–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Bradley A., William Wells, and William King. 2021. What happens when sexual assault kits go untested? A focal concerns analysis of suspect identification and pre-arrest decisions. Journal of Criminal Justice 76: 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Rebecca, Debra Patterson, Deborah Bybee, and Emily R. Dworkin. 2009. Predicting sexual assault prosecution outcomes: The role of medical forensic evidence collected by sexual assault nurse examiners. Criminal Justice and Behavior 36: 712–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casi, Herve M. 1998. KR20: Stata module to calculate Kuder-Richardson coefficient of reliability. In Statistical Software Components S351001. Boston: Boston College Department of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, Susan M., and Martha Torney. 1981. The decisions and processing of rape victims through the criminal justice system. California Sociologist 4: 155–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yingyu, and Sarah E. Ullman. 2010. Women’s reporting of sexual and physical assaults to police in the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women 16: 262–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, Nils. 1986. The Ideal Victim. In From Crime Policy to Victim Policy. Edited by Ezzat A. Fattah. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clay-Warner, Jody, and Jennifer McMahon-Howard. 2009. Rape reporting: “Classic rape” and the behavior of law. Violence and Victims 24: 723–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwinkel, Elli, Martine Powell, and Patrick Tidmarsh. 2013. Improving police officers’ perceptions of sexual offending through intensive training. Criminal Justice and Behavior 40: 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rue, Lisa, Joshua R. Polanin, Dorothy L. Espelage, and Terri D. Pigott. 2014. School-based interventions to reduce dating and sexual violence: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 7: 1–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoveh, Heidi L., and Lauren Bennett Cattaneo. 2017. Deciding where to turn: A qualitative investigation of college students’ help seeking decisions after sexual assault. American Journal of Community Psychology 59: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Justice—Office of Justice Programs. 2013. Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994–2010; Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Department of Justice—Office of Justice Programs. 2017. National Crime Victimization Survey, 2010–2016; Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Department of Justice—Office of Justice Programs. 2020. National Crime Victimization Survey, 2015–2019; Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Dinis-Oliveria, Ricardo Jorge, and Teresa Magalhaes. 2013. Forensic toxicology in drug- facilitated sexual assault. Toxicology Mechanisms & Methods 23: 471–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dinos, Sokratis, Nina Burrowes, Karen Hammond, and Christina Cunliffe. 2015. A systematic review of juries’ assessment of rape victims: Do rape myths impact on juror-decision making? International Journal of Law, Crime, and Justice 43: 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Louise, and Vanessa E. Munro. 2009. Reacting to rape: Exploring mock jurors assessments of complainant credibility. British Journal of Criminology 49: 202–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EndtheBacklog. 2023. Why the Backlog Exists. Available online: https://www.endthebacklog.org/what-is-the-backlog/why-the-backlog-exists/#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20it%20costs%20between,untested%20in%20police%20storage%20facilities (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Estrich, Susan. 1987. Real Rape. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fansher, Ashley K., and Kayla McCarns. 2019. Risky Online Dating Behaviors and Their Potential for Victimization. Huntsville: Crime Victims’ Institute. Available online: https://www.crimevictimsinstitute.org/pubs/?mode=view&input=84 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Felson, Richard B., and Brendan Lantz. 2015. When are victims unlikely to cooperate with the police? Aggressive Behavior 42: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, Richard B., and Paul-Philippe Paré. 2005. The reporting of domestic violence and sexual assault by nonstrangers to the police. Journal of Marriage and Family 67: 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, Richard B., Steven F. Messner, and Anthony Hoskin. 1999. The victim-offender relationship and calling the police in assaults. Criminology 37: 931–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Bonnie S., Leah E. Daigle, Francis T. Cullen, and Michael G. Turner. 2003. Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: Results from a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice and Behavior 30: 6–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franiuk, Renea, Austin Luca, and Shelby Robinson. 2019. The effects of victim and perpetrator characteristics on ratings of guilt in a sexual assault case. Violence Against Women 26: 614–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, Patricia, Gale Valtinson, and Suzanne Candell. 1994. Evaluation of a coeducational interactive rape prevention program. Journal of Counseling & Development 73: 153–58. [Google Scholar]

- Frohmann, Lisa. 1991. Discrediting victims’ allegations of sexual assault: Prosecutorial accounts of case rejections. Social Problems 38: 213–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, Agatha, Lata Gautam, and Michael D. Cole. 2018. A multifactorial critical appraisal of substances found in drug facilitated sexual assault cases. Forensic Science International 292: 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, Amy, and Emily Turner. 2012. Attribution of blame in rape cases: A review of the impact of rape myth acceptance, gender role conformity and substance use on victim blaming. Aggression and Violent Behavior 17: 443–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, Kris, and Lynette Feder. 2005. Criminal prosecution of domestic violence offenses: An investigation of factors predictive of court outcomes. Criminal Justice and Behavior 32: 612–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, Sophie. 2021. Why Didn’t She Fight Back? An Exploration of Victim Blaming through Tonic Immobility Reactions to Sexual Violence. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Worcester, Worcester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Judith Lewis. 2003. The mental health of crime victims: Impact of legal intervention. Journal of Traumatic Stress 16: 159–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamel, Joanna. 2010. Researching the provision of service to rape victims by specially trained police officers: The influence of gender–an exploratory study. New Criminal Law Review 13: 688–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalven, Harry, and Hans Zeisel. 1971. The American Jury. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitány-Fövény, Mátá, Gábor Zacher, János Posta, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2017. GHB-involved crimes among intoxicated patients. Forensic Science International 275: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Koss, Mary P., Thomas E. Dinero, Cynthia A. Seibel, and Susan L. Cox. 1988. Stranger and acquaintance rape: Are there differences in the victim’s experience? Psychology of Women Quarterly 12: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsey, David S., Jr., Bradley A. Campbell, and Bryant T. Plumlee. 2022. Focal concerns and police decision making in sexual assault cases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 23: 1220–34. [Google Scholar]

- Larcombe, Wendy. 2002. The ‘ideal’ victim v successful rape complainants: Not what you might expect. Feminist Legal Studies 10: 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathan, Emma, Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Jessica Duncan, and James “Tres” Stefurak. 2019. The Promise Initiative: Promoting a trauma-informed police response to sexual assault in a mid-size Southern community. Journal of Community Psychology 47: 1733–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisak, David, and Paul M. Miller. 2002. Repeat rape and multiple offending among undetected rapists. Violence and Victims 17: 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisak, David, Lori Gardinier, Ssarah C. Nicksa, and Ashley M. Cote. 2010. False allegations of sexual assault: An analysis of ten years of reported cases. Violence against Women 16: 1318–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, Lucy, Deborah Lee, and Chris Barker. 2011. Police empathy and victim PTSD as potential factors in rape case attrition. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 26: 112–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCahill, Thomas W., Linda C. Meyer, and Arthur M. Fischman. 1979. The Aftermath of Rape. Lexington: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Margaret J., Grace Le, Stephen A. Marion, and Ellen Wiebe. 1999. Examination for sexual assault: Is the documentation of physical injury associated with the laying of charges? A retrospective cohort study. Canadian Medical Association 160: 1565–69. [Google Scholar]

- Miethe, Terance D. 1987. Stereotypical conceptions and criminal processing: The case of the victim-offender relationship. Justice Quarterly 4: 571–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, Melissa Schaefer, April Pattavina, and Linda M. Williams. 2019. It all just piles up: Challenges to victim credibility accumulate to influence sexual assault case processing. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 3151–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, Martha A., and John Hagan. 1979. Private and public trouble: Prosecutors and the allocation of court resources. Social Problems 26: 439–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Steve, and Menachem Amir. 1975. The hitchhike victim of rape: A research report. Victimology: A New Focus 3: 103–27. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal, Eryn Nicole, Katharine Tellis, and Cassia Spohn. 2015. Prosecuting intimate partner sexual assault: Legal and extra-legal factors that influence charging decisions. Violence Against Women 21: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattavina, April, Melissa Schaefer Morabito, and Linda M. Williams. 2021. Pathways to sexual assault case attrition: Culture, context, and case clearance. Victims & Offenders 16: 1061–76. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, Debra. 2011. The impact of detectives’ manner of questioning on rape victims’ disclosure. Violence against Women 17: 1349–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Debra, Megan Greeson, and Rebecca Campbell. 2009. Understanding rape survivors’ decisions not to seek help from formal social systems. Health and Social Work 14: 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAINN. 2023. Perpetrators of Sexual Violence: Statistics. RAINN. Available online: https://www.rainn.org/statistics/perpetrators-sexual-violence (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Ruback, R. Barry, and Deborah L. Ivie. 1988. Prior relationship, resistance, and injury in rapes: An analysis of crisis center records. Violence and Victims 3: 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Leonore M. J. 1996. Legal treatment of the victim-offender relationship in crimes of violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 11: 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, Shringika, Utkarsh Jain, and Nidhi Chauhan. 2021. A systematic review on sensing techniques for drug-facilitated sexual assaults (DFSA) monitoring. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry 49: 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, Jeffrey, and Cassia Spohn. 1997. The effect of evidence factors and victim characteristics on prosecutors’ charging decisions in sexual assault cases. Justice Quarterly 14: 501–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Chelsea M., and Sandra M. Stith. 2020. Risk factors for male perpetration and female victimization of intimate partner homicide: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 21: 527–40. [Google Scholar]

- Spohn, Cassia C., and David Holleran. 2001. Prosecuting sexual assault: A comparison of charging decisions in sexual assault cases involving strangers, acquaintances, and intimate partners. Justice Quarterly 18: 651–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, Cassia C., and Jeffrey W. Spears. 1996. The effect of offender and victim characteristics on sexual assault case processing decisions. Justice Quarterly 13: 649–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, Cassia C., and Julie Horney. 1993. Rape law reform and the effect of victim characteristics on case processing. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 9: 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, Cassia C., and Katherine Tellis. 2012. The criminal justice system’s response to sexual violence. Violence Against Women 18: 169–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spohn, Cassia C., and Katherine Tellis. 2019. Sexual assault case outcomes: Disentangling the overlapping decisions of police and prosecutors. Justice Quarterly 36: 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, Cassia C., Dawn Beichner, and Erika Davis-Frenzel. 2001. Prosecutorial justifications for sexual assault case rejection: Guarding the “gateway to justice”. Social Problems 48: 206–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, Cassia C., Dawn Beichner, Erika Davis Frenzel, and David Holleran. 2002. Prosecutors’ Charging Decisions in Sexual Assault Cases: A Multi-Site Study, Final Report; Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

- Stanko, Elizabeth Anne. 1981. The impact of victim assessment on prosecutors’ screening decisions: The case of the New York County District Attorney’s Office. Law & Society Review 16: 225. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier, Darrell, Jeffrey Ulmer, and John Kramer. 1998. The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: The punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology 36: 763–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Natalie, and Jacqueline Joudo Larsen. 2005. The Impact of Pre-Recorded Video and Closed-Circuit Testimony by Adult Sexual Assault Complaints on Jury-Decision Making: An Experimental Study; Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=9a40686d590f47f31f545d1ee5d3a03ea6db5ccd (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Taylor, Steven M. 2022. Unfounding the ideal victim: Does Christie’s ideal victim explain police response to intimate partner sexual assault? Violence and Victims 37: 201–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellis, Katherine M., and Cassia C. Spohn. 2008. The sexual stratification hypothesis revisited: Testing assumptions about simple versus aggravated rape. Journal of Criminal Justice 36: 252–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Lauren E., Emily Pica, and Joanna Pozzulo. 2021. Jurors’ decision making in a sexual assault trial: The influence of victim age, delayed reporting, and multiple allegations. American Journal of Forensic Psychology 39: 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tidmarsh, Patrick, Gemma Hamilton, and Stefanie J. Sharman. 2020. Changing police officers’ attitudes in sexual offense cases: A 12-month follow-up study. Criminal Justice and Behavior 47: 1176–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, Patricia Godeke, and Nancy Thoennes. 2006. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Rape Victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

- Ullman, Sarah E., and Judith M. Siegel. 1993. Victim-offender relationship and sexual assault. Violence and Victims 8: 121–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussery, Camas. 2022. The myth of the “ideal victim”: Combatting misconceptions of expected demeanour in sexual assault survivors. Appeal: Rev. Current Law., and Legal Reform 27: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vrees, Roxanne A. 2017. Evaluation and management of female victims of sexual assault. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 72: 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Whatley, Mark A. 1996. Victim characteristics influencing attributions of responsibility to rape victims: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior 1: 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, Robert E., Sarah J. McLean, Robin S. Engel, Hannah Cochran, Nicholas Corsaro, Danielle Reynolds, Cynthia J. Najdowski, and Gabrielle T. Isaza. 2020. The Impacts of Implicit Bias Awareness Training in the NYPD. Albany: The John F. Finn Institute for Public Safety, Inc. Cincinnati: The Center for Police Research and Policy at the University of Cincinnati. [Google Scholar]

- Zilkens, Renate R., Debbie A. Smith, Maire C. Kelly, S. Aqif Mukhtar, James B. Semmens, and Maureen A. Phillips. 2017. Sexual assault and general body injuries: A detailed cross-sectional Australian study of 1163 women. Forensic Science International 279: 112–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Incident Characteristics | n (M) | % (SD) | Min/Max | χ2/t (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assault type | 0–4 | 31.067 (<0.001) | ||

| Multiple types of penetration | 133 | 19.00 | ||

| Anal penetration | 35 | 3.57 | ||

| Vaginal penetration | 389 | 55.57 | ||

| Oral penetration | 25 | 5.00 | ||

| No penetration | 118 | 19.00 | ||

| Victim/offender relationship | 0–2 | 21.757 (<0.001) | ||

| Current or former romantic partners | 195 | 27.86 | ||

| Other known offender | 290 | 41.43 | ||

| Strangers | 185 | 26.43 | ||

| Location | 0–2 | 9.543 (0.008) | ||

| Victim’s/mutual residence | 232 | 33.14 | ||

| Other residence | 267 | 38.14 | ||

| Other location | 196 | 28.00 | ||

| Time of assault | 0–1 | 3.373 (0.066) | ||

| Daytime (7 a.m.–7 p.m.) | 234 | 33.43 | ||

| Nighttime (7 p.m.–7 a.m.) | 433 | 61.86 | ||

| Presence of witnesses | 0–1 | 6.425 (0.011) | ||

| At least 1 witness present | 226 | 32.29 | ||

| No witnesses reported | 463 | 66.14 | ||

| SANE conducted | 0–1 | 0.104 (0.747) | ||

| Yes | 470 | 67.14 | ||

| No | 227 | 32.43 | ||

| Victim characteristics | ||||

| Sex | 0–1 | 0.282 (0.596) | ||

| Female | 669 | 95.57 | ||

| Male | 31 | 4.43 | ||

| Race | 1–3 | |||

| White | 356 | 50.86 | 2.662 (0.103) | |

| Black | 298 | 42.57 | 3.319 (0.068) | |

| Other | 45 | 6.43 | 0.121 (0.728) | |

| Age | (30.96) | (11.29) | 17–84 | −0.669 (0.504) |

| Resistance used | 0–1 | 0.414 (0.520) | ||

| Physical or verbal resistance | 522 | 74.57 | ||

| No resistance noted | 178 | 25.43 | ||

| Injuries present | 0–1 | 17.138 (<0.001) | ||

| Yes | 186 | 26.57 | ||

| None noted | 514 | 73.43 | ||

| Under the influence | 0–1 | 6.257 (0.012) | ||

| Substances noted in the report | 223 | 31.86 | ||

| No substances noted | 477 | 68.14 | ||

| Suspected “date rape” drugs | 0–1 | 14.970 (<0.001) | ||

| Yes | 90 | 12.86 | ||

| Not indicated in the report | 608 | 87.11 | ||

| Credibility/mental health issues | 0–1 | 2.572 (0.109) | ||

| Yes | 55 | 7.86 | ||

| Not indicated in report | 645 | 92.14 | ||

| Criminal record | 0–2 | 0.389 (0.823) | ||

| None | 489 | 69.86 | ||

| One type of offense | 101 | 14.43 | ||

| Multiple types of offenses | 52 | 7.43 | ||

| Initially cooperative | 0–1 | 0.702 (0.402) | ||

| Yes | 671 | 95.86 | ||

| No | 27 | 3.87 | ||

| Stayed cooperative | 0–1 | 8.850 (0.003) | ||

| Yes | 540 | 77.14 | ||

| No | 123 | 18.41 | ||

| Delayed reporting | 0–1 | 26.612 (<0.001) | ||

| Reported within 1 day | 538 | 76.87 | ||

| Delayed by more than 1 day | 162 | 23.14 | ||

| Suspect characteristics | ||||

| Sex | 0–1 | 0.563 (0.755) | ||

| Male | 690 | 98.57 | ||

| Female | 8 | 1.14 | ||

| Race | 1–3 | |||

| White | 208 | 29.71 | 0.004 (0.948) | |

| Black | 429 | 61.29 | 0.521 (0.470) | |

| Other | 62 | 8.86 | 1.797 (0.180) | |

| Age | (37.33) | (12.05) | 17–84 | −1.602 (0.110) |

| Weapon used | 0–1 | 16.213 (<0.001) | ||

| Yes | 130 | 18.57 | ||

| No weapon noted | 570 | |||

| Criminal record | 81.43 | 0–2 | 13.604 (0.001) | |

| None | 343 | 49.00 | ||

| One type of offense | 150 | 21.43 | ||

| Multiple types of offenses | 141 | 20.14 | ||

| Sexual assault charge history | 0–1 | 23.498 (<0.001) | ||

| Yes | 36 | 5.14 | ||

| No history noted | 598 | 94.32 |

| n | % | Min/Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal penetration | 520 | 74.29 | 0–1 |

| Strangers | 185 | 26.43 | 0–1 |

| Victim’s residence | 232 | 33.14 | 0–1 |

| Daytime (7 a.m.–7 p.m.) | 234 | 33.43 | 0–1 |

| White victim | 356 | 50.86 | 0–1 |

| Elderly victims (65+) | 7 | 1.00 | 0–1 |

| No substances present | 477 | 68.14 | 0–1 |

| No credibility issues | 645 | 92.14 | 0–1 |

| Injuries present | 186 | 26.57 | 0–1 |

| Victim resisted | 522 | 74.57 | 0–1 |

| M | SD | Min/Max | |

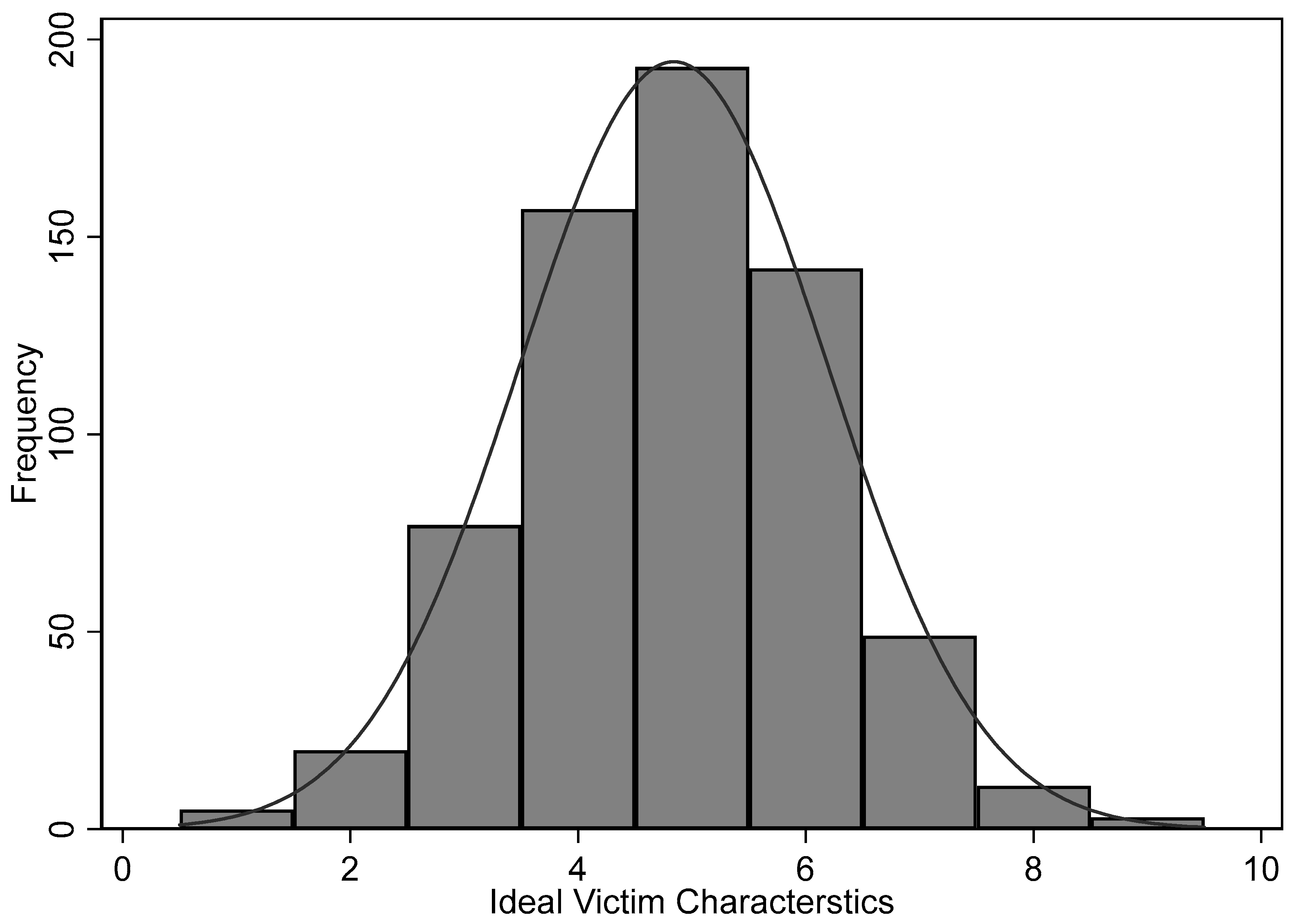

| “Ideal victim” scale | 4.84 | 1.35 | 1–10 |

| b | SE | Std. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal victim | 0.136 | 0.081 | 0.089 |

| Victim/offender relationship: Partners | −0.461 | 0.242 | −0.102 * |

| Assault Location: Non-residence | 0.104 | 0.244 | 0.022 |

| Witness(es) | 0.494 | 0.212 | 0.113 * |

| SANE conducted | −0.255 | 0.246 | −0.056 |

| Victim sex (1 = Female) | 0.152 | 0.495 | 0.016 |

| Suspected “date rape” drugs | −1.166 | 0.385 | −0.190 ** |

| Victim criminal history | −0.099 | 0.174 | −0.030 |

| Initial cooperation | −0.334 | 0.573 | −0.031 |

| Continued cooperation | 0.998 | 0.308 | 0.188 *** |

| Delayed reporting (0 = Report within 1 day) | −0.965 | 0.303 | −0.191 *** |

| Suspect sex (1 = Female) | 0.784 | 1.129 | 0.037 |

| Suspect race (1 = White) | 0.455 | 0.234 | 0.100 * |

| Suspect age | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.075 |

| Weapon used | 0.836 | 0.256 | 0.157 *** |

| Suspect criminal history | 0.177 | 0.136 | 0.070 |

| Suspect history of sexual assault | 1.292 | 0.468 | 0.144 ** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.128 *** | ||

| B | SE | Std. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal penetration | −0.802 | 0.295 | −0.155 ** |

| Victim/offender relationship | |||

| Partners | −0.383 | 0.289 | −0.081 |

| Strangers | 0.811 | 0.274 | 0.161 ** |

| Assault location | |||

| Victim/mutual residence | 0.439 | 0.269 | 0.096 |

| Non-residence | 0.126 | 0.285 | 0.026 |

| Time (1 = 7 a.m.–7 p.m.) | 0.017 | 0.225 | 0.004 |

| Witness(es) | 0.403 | 0.222 | 0.088 |

| SANE conducted | 0.114 | 0.286 | 0.024 |

| Victim sex (1 = Female) | 0.807 | 0.544 | 0.080 |

| Victim race (0 = Non-white) | −0.248 | 0.242 | −0.057 |

| Victim age | −0.012 | 0.011 | −0.060 |

| Resistance used | −0.180 | 0.268 | −0.035 |

| Physical injuries present | 0.677 | 0.243 | 0.139 ** |

| Victim substance use (1 = No issues) | 0.035 | 0.259 | 0.008 |

| Suspected “date rape” drugs | −1.300 | 0.412 | −0.202 ** |

| Victim credibility (1 = No issues) | 0.732 | 0.437 | 0.090 |

| Victim criminal history | −0.159 | 0.184 | −0.045 |

| Initial cooperation | −0.351 | 0.584 | −0.031 |

| Continued cooperation | 1.032 | 0.314 | 0.185 *** |

| Delayed reporting (0 = Report within 1 day) | −0.774 | 0.313 | −0.146 ** |

| Suspect sex (1 = Female) | 1.123 | 1.236 | 0.050 |

| Suspect race (1 = White) | 0.694 | 0.265 | 0.146 ** |

| Suspect age | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.117 * |

| Weapon used | 0.582 | 0.277 | 0.104 * |

| Suspect criminal history | 0.145 | 0.144 | 0.055 |

| Suspect history of sexual assault | 1.298 | 0.475 | 0.138 *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.173 *** | ||

| B | SE | Std. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal penetration | −0.583 | 0.255 | −0.113 * |

| Injuries present | 0.816 | 0.236 | 0.171 *** |

| Strangers | 0.951 | 0.249 | 0.193 ** |

| Witness(es) present | 0.415 | 0.229 | 0.092 |

| Suspected “date rape” drugs | −1.579 | 0.428 | −0.250 *** |

| Delayed reporting | −0.400 | 0.155 | −0.173 ** |

| Suspect history of sexual assault | 1.891 | 0.534 | 0.210 *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.157 *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fansher, A.K.; Welsh, B. A Decade of Decision Making: Prosecutorial Decision Making in Sexual Assault Cases. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060348

Fansher AK, Welsh B. A Decade of Decision Making: Prosecutorial Decision Making in Sexual Assault Cases. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(6):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060348

Chicago/Turabian StyleFansher, Ashley K., and Bethany Welsh. 2023. "A Decade of Decision Making: Prosecutorial Decision Making in Sexual Assault Cases" Social Sciences 12, no. 6: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060348

APA StyleFansher, A. K., & Welsh, B. (2023). A Decade of Decision Making: Prosecutorial Decision Making in Sexual Assault Cases. Social Sciences, 12(6), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060348