Imagining Decent Work towards a Green Future in a Former Forest Village of the City of Istanbul

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The Context

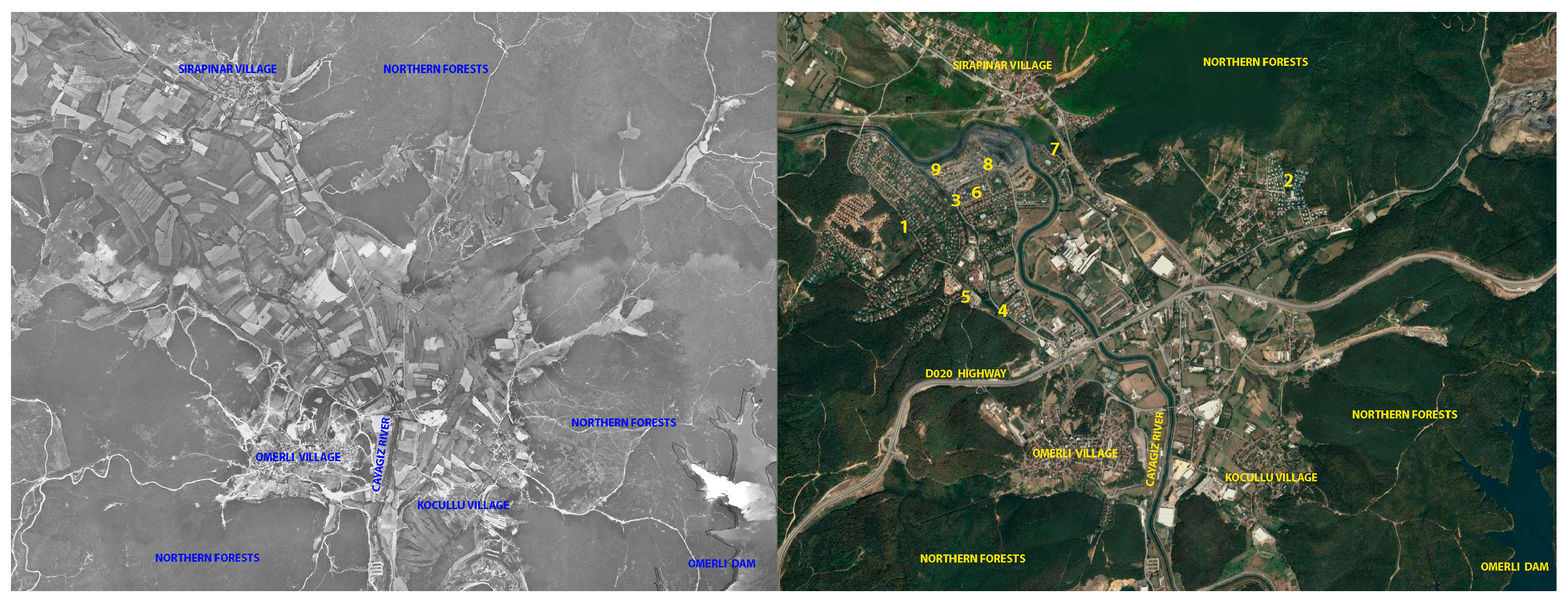

In the Outskirts of the Megacity

4. Research Method

5. Findings

5.1. The Abandoned Lifestyle and Extinct Forms of Work

Following the communal bush gathering from the forest, women from each family brought their bread dough and collective baking took place once a week. Women also communally hand washed laundry in the fresh water from the hills, and harvested wheat and rice together.

My grandmother used to weave linen cloth at home like other women of the village using a handloom. They hand dyed the textiles using oak leaves.

Our resistance to the environmental impact assessment report was not taken seriously. I made sure a critical commentary was added to the report, highlighting the arable quality of the construction site. First, they poured rubble on the land. Then they took samples from the soil and reported that the arable quality of the land was lost.

This administrative change marked the beginning of the exploitation of Ömerli. It ended the practice of renting out the grazing land of the village pasture to provide income to maintain the community house and the Mosque. Construction activity that received approval from the municipality destroyed the grazing land.

a strenuous activity that required bodily strength; and having observed many who fell ill, I suspect that it may have caused illnesses in workers born between 1945 and the 1960s.

5.2. The New and the Surviving Types of Work

5.2.1. Proletarianisation of the Villagers by Catering Services for Middle-Class New Residents

For most of these investors, a feasible business idea led to insolvency due to the spiral of debt in which they fell. Having lost their property, many of them had to sell their trucks, ending up as wage labourers, as drivers of the trucks they previously owned. These makeshift drivers are today at the service of construction companies carrying rubble between the construction sites and dumping areas.

5.2.2. New Jobs Relying on Community-Based Resources

Harvesting cochina is hard work. It is only found in dense thornbush in the forest. We go in as a family and even if we wear gloves and boots, our entire bodies end up bleeding from the scars of the thorny plants. Immediately after harvest, my family enters a marathon of tying two different kinds of plants, the green bushes to the red flowers, aesthetically. This is difficult. Not everyone in the family is good at it. I am better, so I get to do a lot of the work. We continue to tie the flowers day and night, losing sleep for weeks throughout November.

5.2.3. The Surviving and the Revived Jobs

5.3. The Community Fungi Initiative

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acar, Sevil, Ahmet Atıl Aşıcı, and A. Erinç Yeldan. 2022. Potential Effects of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on the Turkish Economy. Environment, Development and Sustainability 24: 8162–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaman, Fikret, and Bengi Akbulut. 2021. Erdoğan’s Three-Pillared Neoliberalism: Authoritarianism, Populism and Developmentalism. Geoforum 124: 279–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adly, Amr. 2021. Authoritarian Restitution in Bad Economic Times Egypt and the Crisis of Global Neoliberalism. Geoforum 124: 290–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsel, Murat, Fikret Adaman, and Alfredo Saad-Filho. 2021. Authoritarian Developmentalism: The Latest Stage of Neoliberalism? Geoforum 124: 261–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwood, Loka, Noelle Harden, Michael M. Bell, and William Bland. 2014. Linked and Situated: Grounded Knowledge: Linked and Situated: Grounded Knowledge. Rural Sociology 79: 427–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysev, Evren. 2022. Urbanization Processes of Northern Istanbul in the 2000’s: Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge and the Northern Marmara Highway. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 39: 137–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke, eds. 2002. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchly, Richard, Zeynep Delen Nircan, and Patricia O’Hara. 2017. The Chemical Story of Olive Oil: From Grove to Table. London: Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi, Patrick. 2019. Work and Social-Ecological Transitions: A Critical Review of Five Contrasting Approaches. Sustainability 11: 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Özlem. 2021. The Roles of the State in the Financialisation of Housing in Turkey. Housing Studies, 1–21, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevresel Etki Değerlendirmesi, İzin ve Denetim Genel Müdürlüğü. n.d. İl Çevre Durum Raporları. Available online: https://ced.csb.gov.tr/il-cevre-durum-raporlari-i-82671 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Chomsky, Noam, Robert Pollin, and Chronis Polychroniou. 2020. Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Curley, Andrew. 2018. A Failed Green Future: Navajo Green Jobs and Energy ‘Transition’ in the Navajo Nation. Geoforum 88: 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordmond, Gertjan, Heder Carlos de Oliveira, Ivair Ramos Silva, and Julia Swart. 2021. The Complexity of Green Job Creation: An Analysis of Green Job Development in Brazil. Environment, Development and Sustainability 23: 723–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, Selçuk. 2007. Forest and the State: History of Forestry and Forest Administration in the Ottoman Empire. Ph.D. dissertation, Sabancı University, İstanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Enlil, Zeynep, and İclal Dinçer. 2022. Political Dilemmas in the Making of a Sustainable City-Region: The Case of Istanbul. Sustainability 14: 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, Christoph, Ana Sofía Rojo Brizuela, and Daniele Epifanio. 2020. Green Jobs in Argentina: Opportunities to Move Forward with the Environmental and Social Agenda. CEPAL Review 2019: 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchart, Linda. 2022. Indigenous Movements. In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 253–54. [Google Scholar]

- Farooquee, Nehal A., B. S. Majila, and C. P. Kala. 2004. Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Sustainable Management of Natural Resources in a High Altitude Society in Kumaun Himalaya, India. Journal of Human Ecology 16: 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, Giuseppe, Michael K. Goodman, Jaime Suzunaga, and Jenny Soler. 2023. Collective Memories, Place-Framing and the Politics of Imaginary Futures in Sustainability Transitions and Transformation. Geoforum 138: 103668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Vaquero, Martín, Antonio Sánchez-Bayón, and José Lominchar. 2021. European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies 14: 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geniş, Şerife. 2007. Producing Elite Localities: The Rise of Gated Communities in Istanbul. Urban Studies 44: 771–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good Work Index|Survey Reports. n.d. CIPD. Available online: https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/work/trends/goodwork (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Grasso, Maria T., and Marco Giugni, eds. 2022. The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements. Routledge International Handbooks. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Green Jobs Initiative Report. 2008. Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World. UNEP, ILO, IOE, ITUC. Available online: https://www.ioe-emp.org/fileadmin/ioe_documents/publications/Policy%20Areas/environment_and_climate_change/EN/UNEP__IOE__ILO__ITUC_Report_-Towards_decent_work_in_a_sustainable__low-carbon_world__Sept._2008_.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Guha, Ramachandra. 2000. The Unquiet Woods: Ecological Change and Peasant Resistance in the Himalaya, Expanded ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gülhan, Sinan Tankut. 2022. Neoliberalism and Neo-Dirigisme in Action: The State–Corporate Alliance and the Great Housing Rush of the 2000s in Istanbul, Turkey. Urban Studies 59: 1443–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, Elmira Ayşe, and Yurdanur Dülgeroğlu Yüksel. 2019. Analytical Investigation of Urban Housing Typologies in Twentieth Century Istanbul. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 13: 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Jinghui, Yulin Dong, Zhibin Ren, Yunxia Du, Chengcong Wang, Guangliang Jia, Peng Zhang, and Yujie Guo. 2021. Remarkable Effects of Urbanization on Forest Landscape Multifunctionality in Urban Peripheries: Evidence from Liaoyuan City in Northeast China. Forests 12: 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, Garrett. 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 162: 1243–48. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1724745 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Hecht, Susanna B., and Alexander Cockburn. 2010. The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers, and Defenders of the Amazon, Updated ed. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- İSMEK. n.d. Available online: https://enstitu.ibb.istanbul/portal/default.aspx (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Karatepe, Ismail Doga. 2021. The Cultural Political Economy of the Construction Industry in Turkey: The Case of Public Housing. International Comparative Social Studies. Leiden: Brill, vol. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Kiely, Ray. 2021. Conservatism, Neoliberalism and Resentment in Trumpland: The ‘Betrayal’ and ‘Reconstruction’ of the United States. Geoforum 124: 334–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, Bekir. 2005. 1870 Orman Nizamnamesi’nin Osmanlı Ormancılığına Katkısı Üzerine Bazı Notlar—Some Notes on 1870 Forest Nizamname’s (Regulation) contrubition to the Otoman Forestry. Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi Tarih Bölümü Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi 24: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, Rosa, and Amelia Clarke. 2014. Framing ‘Green Jobs’ Discourse: Analysis of Popular Usage: Popular Usage of ‘Green Jobs’. Sustainable Development 22: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzey Ormanları Araştırma Derneği. n.d. Available online: https://kuzeyormanlariarastirma.org (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Littig, Beate. 2017. Good ‘Green Jobs’ for Whom? A Feminist Critique of the ‘Green Economy’. In International Handbook on Gender and Environment. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean, Rupert, Shanti Jagannathan, and Brajesh Panth. 2018. Education and Skills for Inclusive Growth, Green Jobs and the Greening of Economies in Asia. Technical and Vocational Education and Training: Issues, Concerns and Prospects. Singapore: Springer, vol. 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melles, Gavin, Christian Wölfel, Jens Krzywinski, and Lenard Opeskin. 2022. Expert and Diffuse Design of a Sustainable Circular Economy in Two German Circular Roadmap Projects. Social Sciences 11: 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menteş, Elif, and Evrim Töre. 2020. Rant Etkisinde Zekeriyaköy: Çepere Yönelen Plan, Yatırım ve Kullanıcı Tercihlerine Dair Bir Araştırma. Journal of Planning 30: 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, Dustin. 2014. Are Green Jobs Just Jobs? Cadmium Narratives in the Life Cycle of Photovoltaics. Geoforum 54: 178–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, Derya, and Zafer Yenal. 2020. Seed Politics in Turkey: The Awakening of a Landrace Wheat and Its Prospects. The Journal of Peasant Studies 47: 741–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocejo, Richard. 2017. Masters of Craft: Old Jobs in the New Urban Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Our History|The Green Belt Movement. n.d. Available online: https://www.greenbeltmovement.org/who-we-are/our-history (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Özdemir, Şefika. 2020. Tüketim karıştı yeni yaşam biçimi köye dönüşün medyada sunumu: Yeni köylüler derneği. Erciyes İletişim Dergisi 7: 833–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özhatay, N., A. Byfield, and S. Atay. 2005. Türkiye’nin Önemli Bitki Alanları. İstanbul: Doğal Hayatı Koruma Derneği. [Google Scholar]

- Parrotta, John A., and Mauro Agnoletti. 2007. Traditional Forest Knowledge: Challenges and Opportunities. Forest Ecology and Management 249: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poschen, Peter. 2015. Decent Work, Green Jobs and the Sustainable Economy: Solutions for Climate Change and Sustainable Development, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottinger, Laura. 2016. Planting the Seeds of a Quiet Activism. Area 49: 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Charmaine G. 2021. The Return of Strongman Rule in the Philippines: Neoliberal Roots and Developmental Implications. Geoforum 124: 310–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, Haripriya. 2000. Of Myths and Movements: Rewriting Chipko into Himalayan History. London and New York: VERSO. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, Michael, Sean Sweeney, and Jill Kubit. 2008. Green Jobs: Working for People and the Environment. Worldwatch Report 177. Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Rusterholz, Hans-Peter, Melissa Studer, Valerie Zwahlen, and Bruno Baur. 2020. Plant-Mycorrhiza Association in Urban Forests: Effects of the Degree of Urbanisation and Forest Size on the Performance of Sycamore (Acer Pseudoplatanus) Saplings. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 56: 126872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad-Filho, Alfredo, and Marco Boffo. 2021. The Corruption of Democracy: Corruption Scandals, Class Alliances, and Political Authoritarianism in Brazil. Geoforum 124: 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, Saskia. 1988. The Mobility of Labor and Capital: A Study in International Investment and Labor Flow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiring, Gábor. 2021. Dependent Development and Authoritarian State Capitalism: Democratic Backsliding and the Rise of the Accumulative State in Hungary. Geoforum 124: 267–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, Stephan, Ane Alencar, Hilary Zarin, and Ana Paula Santos Souza. 2010. Social Movements and Large-Scale Tropical Forest Protection on the Amazon Frontier: Conservation From Chaos. The Journal of Environment & Development 19: 274–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Neera M. 2019. Environmental Justice, Degrowth and Post-Capitalist Futures. Ecological Economics 163: 138–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Subir. 2021. ‘Strong Leaders’, Authoritarian Populism and Indian Developmentalism: The Modi Moment in Historical Context. Geoforum 124: 320–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Status and Trends in Traditional Occupations. 2016. Forest Peoples Programme (FPP). Available online: http://www.forestpeoples.org/en/topics/convention-biological-diversity-cbd/publication/2016/status-and-trends-traditional-occupation (accessed on 2 May 2016).

- Stilwell, Frank. 2021. From Green Jobs to Green New Deal: What Are the Questions? The Economic and Labour Relations Review 32: 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, Sarah, Alison Greig, and Aled Jones. 2023. Going Green Post COVID-19: Employer Perspectives on Skills Needs. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 38: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, Adam, and Letycja Sołoducho-Pelc. 2022. The Circular Economy and the Green Jobs Creation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 14231–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tănasie, Anca Vasilica, Luiza Loredana Năstase, Luminița Lucia Vochița, Andra Maria Manda, Geanina Iulia Boțoteanu, and Cătălina Soriana Sitnikov. 2022. Green Economy—Green Jobs in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 14: 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanulku, Basak. 2018. The Formation and Perception of Safety, Danger and Insecurity inside Gated Communities: Two Cases from Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 33: 151–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezer, Azime, Omer Lutfi Sen, İlke Aksehirli, Nuket Ipek Cetin, and Aliye Ceren Tan Onur. 2012. Integrated Planning for the Resilience of Urban Riverine Ecosystems: The Istanbul-Omerli Watershed Case. Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology 12: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togami, Chie, and Suzanne Staggenborg. 2022. Gender and Environmental Movements. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements. New York: Routledge, pp. 423–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Velenturf, Anne P. M., and Phil Purnell. 2021. Principles for a Sustainable Circular Economy. Sustainable Production and Consumption 27: 1437–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicu, Irina, and Stefania Barca. 2020. The Just Transition and Its Work of Inequality. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16: 263–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, Neal D., Jiyoon Kang, and Morgan A. Lowder. 2022. Do Green Policies Produce Green Jobs? Social Science Quarterly 104: 153–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinghe, Huang, and Youn Yeo-Chang. 2021. What Makes the Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge Deteriorate? A Case of Dengcen Village in Southwestern China. Forest Policy and Economics 125: 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Juanwen, Quanxin Wu, and Jinlong Liu. 2012. Understanding Indigenous Knowledge in Sustainable Management of Natural Resources in China. Forest Policy and Economics 22: 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewee | Age | Gender | Pseudonym | Short Biography |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 66 | Male | Mustafa | Local descendant of residents from one of the four major families among the earliest settlers of the Ottoman period. Amateur researcher of regional and family history; university graduate. Career: manager in a multinational corporate company. Current position: retired. |

| 2 | 64 | Male | Mehmet | Local descendant of residents from one of the four major families among the earliest settlers of the Ottoman period (not the same family as that of interviewee 1). Amateur researcher of regional and family history. Local administrator between 1998 and 2004, a family tradition since the late Ottoman era. University graduate. Career: chemist in corporate company; entrepreneur/owner of two local stores. Acted as neighbourhood administrator. Current position: retired. |

| 3 | 65 | Female | Lale | Moved to Istanbul for her secondary education from an Anatolian city in the late 1970s. Joined the Ömerli local community via marriage in the 1980s. University graduate; facilitator and director of local crafts courses offered to women. |

| 4 | 36 | Female | Burcu | Born and raised in Ömerli. Secondary school graduate. Female representative of new forms of work: cleaning and flower trade. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Selçuk, İ.; Nircan, Z.D.; Coşkun, B.S. Imagining Decent Work towards a Green Future in a Former Forest Village of the City of Istanbul. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060342

Selçuk İ, Nircan ZD, Coşkun BS. Imagining Decent Work towards a Green Future in a Former Forest Village of the City of Istanbul. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(6):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060342

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelçuk, İklil, Zeynep Delen Nircan, and Burcu Selcen Coşkun. 2023. "Imagining Decent Work towards a Green Future in a Former Forest Village of the City of Istanbul" Social Sciences 12, no. 6: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060342

APA StyleSelçuk, İ., Nircan, Z. D., & Coşkun, B. S. (2023). Imagining Decent Work towards a Green Future in a Former Forest Village of the City of Istanbul. Social Sciences, 12(6), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060342