Gendering the Political Economy of Smallholder Agriculture: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying a Research Question

2.2. Search Strategy

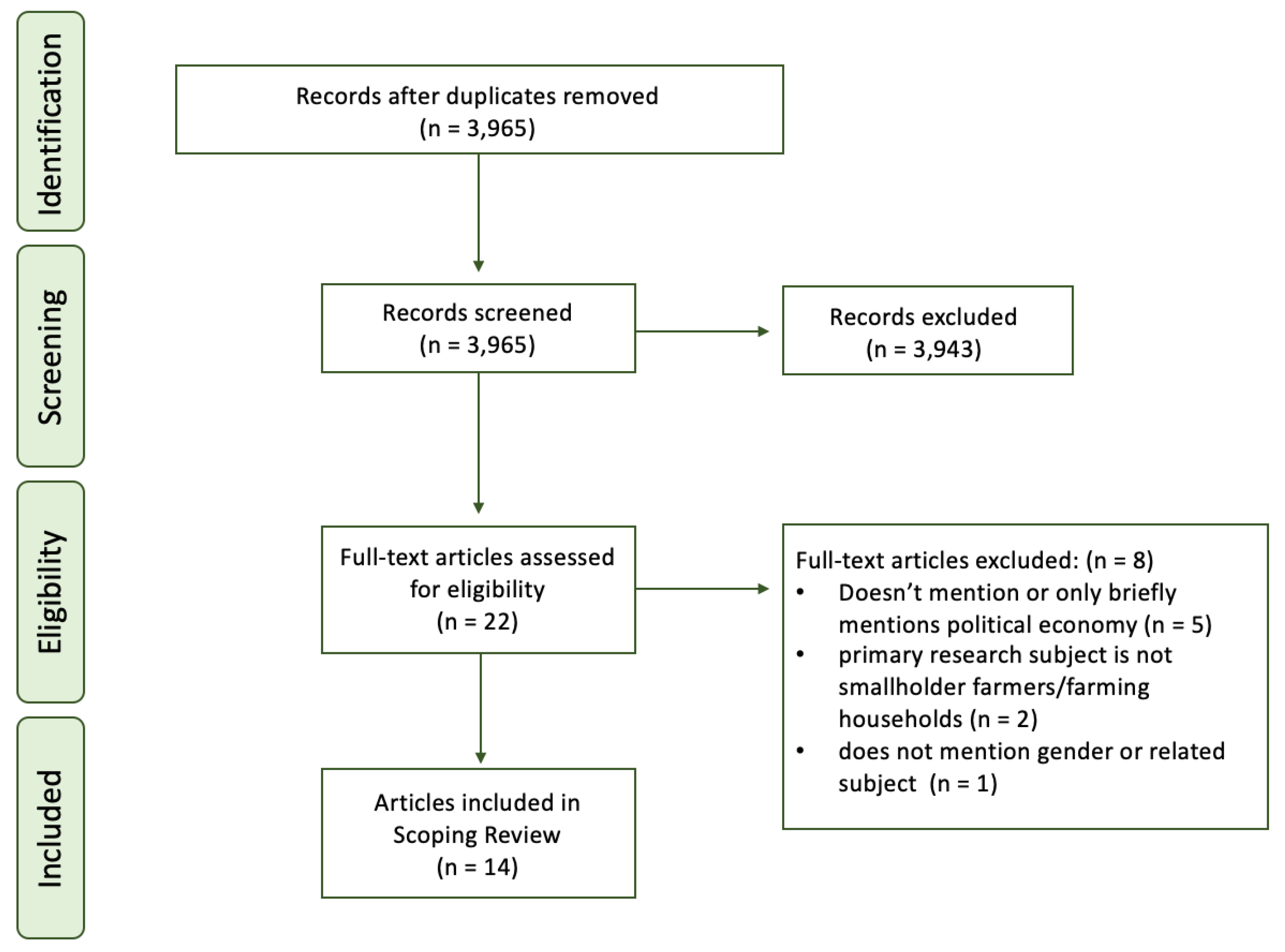

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Results Collation

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Definition of Political Economy

3.3. Why Gender Is Not Included in PE Literature/Frameworks

3.4. How Gender Is Discussed and Analyzed

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Results

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Implications and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abeysekera, Sunila. 2007. Shifting Feminisms: From Inter-Sectionality to Political Ecology. Talking Points 2: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, Aliyu Ahmad, Muhammad Umar Bello, Rozilah Kasim, and David Martin. 2014. Positivist and Non-Positivist Paradigm in Social Science Research: Conflicting Paradigms or Perfect Partners? Journal of Management and Sustainability 4: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Amy. 2016. Feminist Perspectives on Power. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2016 Edition. Edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/feminist-power/ (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Allison, Caroline. 1985. Women, Land, Labour and Survival: Getting Some Basic Facts Straight. IDS Bulletin 16: 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, Leonora C., and Kathryn Hill. 2009. Gender, Place and Culture The Gender Dimension of the Agrarian Transition: Women, Men and Livelihood Diversification in Two Peri-Urban Farming Communities in the Philippines. Gender, Place & Culture 16: 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, Daniel Adu, Comfort Y. Freeman, and Albert Afful. 2020. Gendered Access to Productive Resources—Evidence from Small Holder Farmers in Awutu Senya West District of Ghana. Scientific African 10: e00604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, Neil. 1999. Inside the Black Box: Dimensions of Gender, Generation and Scale in the Australian Rural Restructuring Process. Journal of Rural Studies 15: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, Lisa. 2012. The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—An Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health 102: 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, Renee, Amos Gyau, Dagmar Mithoefer, and Marilyn Swisher. 2018. Contracting and Gender Equity in Tanzania: Using a Value Chain Approach to Understand the Role of Gender in Organic Spice Certification. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 33: 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of the Identity. In Thinking Gender. Edited by Linda J. Nicholson. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, Avery S., Peter Newton, Juliana D. B. Gil, Laura Kuhl, Leah Samberg, Vincent Ricciardi, Jessica R. Manly, and Sarah Northrop. 2017. Smallholder Agriculture and Climate Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42: 347–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deere, Carmen Diana. 1995. What Difference Does Gender Make? Rethinking Peasant Studies. Feminist Economics 1: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürr, Jochen. 2016. The Political Economy of Agriculture for Development Today: The ‘Small versus Large’ Scale Debate Revisited. Agricultural Economics (United Kingdom) 47: 671–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Shenggen, and Christopher Rue. 2020. The Role of Smallholder Farms in a Changing World. In The Role of Smallholder Farms in Food and Nutrition Security. Edited by Sergio Gomez Paloma, Laura Riesgo and Kamel Louhichi. Berlin: Springer, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhall, Kate, and Lauren Rickards. 2021. The ‘Gender Agenda’ in Agriculture for Development and Its (Lack of) Alignment With Feminist Scholarship. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonjong, Lotsmart N., and Adwoa Y. Gyapong. 2021. Plantations, Women, and Food Security in Africa: Interrogating the Investment Pathway towards Zero Hunger in Cameroon and Ghana. World Development 138: 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Yihong. 2007. Legitimacy of Foreign Language Learning and Identity Research: Structuralist and Constructivist Perspectives. Intercultural Communication Studies 16: 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Georgeou, Nichole, Charles Hawksley, James Monks, and Melina Ki’i. 2019. Food Security and Asset Creation in Solomon Islands: Gender and the Political Economy of Agricultural Production for Honiara Central Market. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies 16: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, Barbara. 1989. Differential female mortality and health care in South Asia. The Journal of Social Studies 44: 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, Christine, Florence Kyazze, Jesse Naab, Sharmind Neelormi, James Kinyangi, Robert Zougmore, Pramod Aggarwal, Gopal Bhatta, Moushumi Chaudhury, Marja-Liisa Tapio-Bistrom, and et al. 2015. Understanding Gender Dimensions of Agriculture and Climate Change in Smallholder Farming Communities. Climate and Development 8: 133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, Paula, Miranda Morgan, and Afrina Choudhury. 2015. Amplifying Outcomes by Addressing Inequality: The Role of Gender-Transformative Approaches in Agricultural Research for Development. Gender, Technology and Development 19: 292–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Max, and Hubert Buch-Hansen. 2021. In Search of a Political Economy of the Postgrowth Era. Globalizations 18: 1219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, Erika Jean. 2016. Does Coffee Matter? Women and Development in Rwanda. Master of Arts Thesis, The Department of Political Science, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Zhibin, and Lixin Zhang. 2007. Gender, Land and Local Heterogeneity. Journal of Contemporary China 15: 637–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, Fiona. 1993. Exploring the Connections: Structural Adjustment, Gender and the Environment. Geoforum 24: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Shangyi, Rachel Connelly, and Xinxin Chen. 2017. Stuck in the Middle: Off-Farm Employment and Caregiving Among Middle-Aged Rural Chinese. Feminist Economics 4: 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, Karl. 1969. Theories of Surplus Value. Edited by S. Ryazanskaya. Moscow: Progress Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Masamha, Blessing, Vusilizwe Thebe, and Veronica N. E. Uzokwe. 2017. Mapping Cassava Food Value Chains in Tanzania’s Smallholder Farming Sector: The Implications of Intra-Household Gender Dynamics. Journal of Rural Studies 58: 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbilinyi, Marjorie. 2016. Analysing the History of Agrarian Struggles in Tanzania from a Feminist Perspective. Review of African Political Economy 43: 115–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, Hanson. 2017. Agricultural Diversification and Dietary Diversity: A Feminist Political Ecology of the Everyday Experiences of Landless and Smallholder Households in Northern Ghana. Geoforum 86: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Spike V. 2006. How (the Meaning of) Gender Matters in Political Economy. New Political Economy 10: 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quisumbing, Agnes R., Deborah Rubin, Cristina Manfre, Elizabeth Waithanji, Mara van den Bold, Deanna Olney, and Ruth S. Meinzen-Dick. 2014. Closing the Gender Asset Gap: Learning from Value Chain Development in Africa and Asia. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, Shahra. 2009. Engendering the Political Economy of Agrarian Change. Journal of Peasant Studies 36: 197–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Carolyn, Lemlem Aregu, Afrina Choudhury, Surendran Rajaratnam, Margreet van der Burg, and Cynthia McDougall. 2019. Implications of Agricultural Innovation on Gender Norms. In Gender, Agriculture and Agrarian Transformations. Edited by Carolyn Sachs. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifaki, Eleni. 2019. Women’s Work and Agency in GPNS during Economic Crises: The Case of the Greek Table Grapes Export Sector. Feminist Economics 25: 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, Kaitlyn, and Maria Elisa Christie. 2020. Renegotiating Gender Roles and Cultivation Practices in the Nepali Mid-Hills: Unpacking the Feminization of Agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 37: 415–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulle, Emmanuel, and Helen Dancer. 2020. Gender, Politics and Sugarcane Commercialisation in Tanzania. Journal of Peasant Studies 47: 973–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, Juanita. 2017. Feminist Political Ecology. International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology 3: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Merisa S. 2019. Cultivating ‘New’ Gendered Food Producers: Intersections of Power and Identity in the Postcolonial Nation of Trinidad. Review of International Political Economy 28: 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, Goedele, and Talip Kilic. 2019. Dynamics of Off-Farm Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Gender Perspective. World Development 119: 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. n.d. Gender and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Young, Iris Marion. 1997. Unruly Categories: A Critique of Nancy Fraser’s Dual Systems Theory. New Left Review 222: 147–60. [Google Scholar]

| Search Terms |

|---|

| AGRICULTURE: agricultur* OR horticultur* OR arable OR smallhold* OR farm? OR farmer? OR farming OR agbio* OR agrofuel* or agrarian* FEMINIST: feminist OR wom?n OR gender* OR female? OR girl? POLITICAL ECONOMY: political economy or political ecology or land policy or land policies or orati?ation OR neo-liberal OR capitalis? OR privati?ation OR economic AND reform? OR government? |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Must specifically reference political economy as a model or framework for the article (i.e., “We draw on New Institutional Economics, political economy and the value chain analysis framework to assess the potential role of contracting to promote gender equity among smallholder organic horticultural producers.” (Bullock et al. 2018, abstract)). Primary research subject or focus of article must be farmers or farming households operating at small scale or subsistence level. Must mention gender or related (women/girls, gender dynamics, feminism). | Does not mention political economy or only mentions political economy briefly or in passing (“i.e., It is not clear whether child mortality or maternal mortality is the key to the political economy of Indian demography” (Harriss 1989, abstract)). primary research subject is not smallholder farmers/farming households. Does not mention gender or related subject. |

| Descriptives | |

| Data type, n | |

| Primary data | 7 |

| Secondary data | 4 |

| Combination | 3 |

| Year of publication n | |

| 1985–1999 | 3 |

| 2000–2014 | 2 |

| 2015–2021 | 9 |

| Location, n | |

| LMICs | 12 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 9 |

| East Asia and the Pacific | 2 |

| The Caribbean | 1 |

| HICs (Australia and Greece) | 2 |

| Categories | Articles | Focus | Goal of Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical gender (n = 7) | (Allison 1985; Bullock et al. 2018; Sifaki 2019; Ankrah et al. 2020; Fonjong and Gyapong 2021) | Differences between experiences of men and women, compared using a measurable variable. | To better understand the complex functioning of households and their individual members. |

| Analytic gender (n = 5) | (Razavi 2009; Mackenzie 1993; Argent 1999; Angeles and Hill 2009; Thompson 2019; Koss 2016) | Formation, interaction, and consolidation of gender roles and dynamics as viewed by individuals, members of other genders, and power systems. | To examine the creation and existence of varying femininities and masculinities within their surrounding political, economic, social, and natural environments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clark, M.; Bandara, S.; Bialous, S.; Rice, K.; Lencucha, R. Gendering the Political Economy of Smallholder Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050306

Clark M, Bandara S, Bialous S, Rice K, Lencucha R. Gendering the Political Economy of Smallholder Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(5):306. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050306

Chicago/Turabian StyleClark, Madelyn, Shashika Bandara, Stella Bialous, Kathleen Rice, and Raphael Lencucha. 2023. "Gendering the Political Economy of Smallholder Agriculture: A Scoping Review" Social Sciences 12, no. 5: 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050306

APA StyleClark, M., Bandara, S., Bialous, S., Rice, K., & Lencucha, R. (2023). Gendering the Political Economy of Smallholder Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences, 12(5), 306. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050306