Cairenes’ Storytelling: Pedestrian Scenarios as a Normative Factor When Enforcing Street Changes in Residential Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the most important technical and functional parts of street design that will guide this change?

- Do pedestrians change the scenarios of their daily movement between activities when the street layouts change, and if so, why does this change occur?

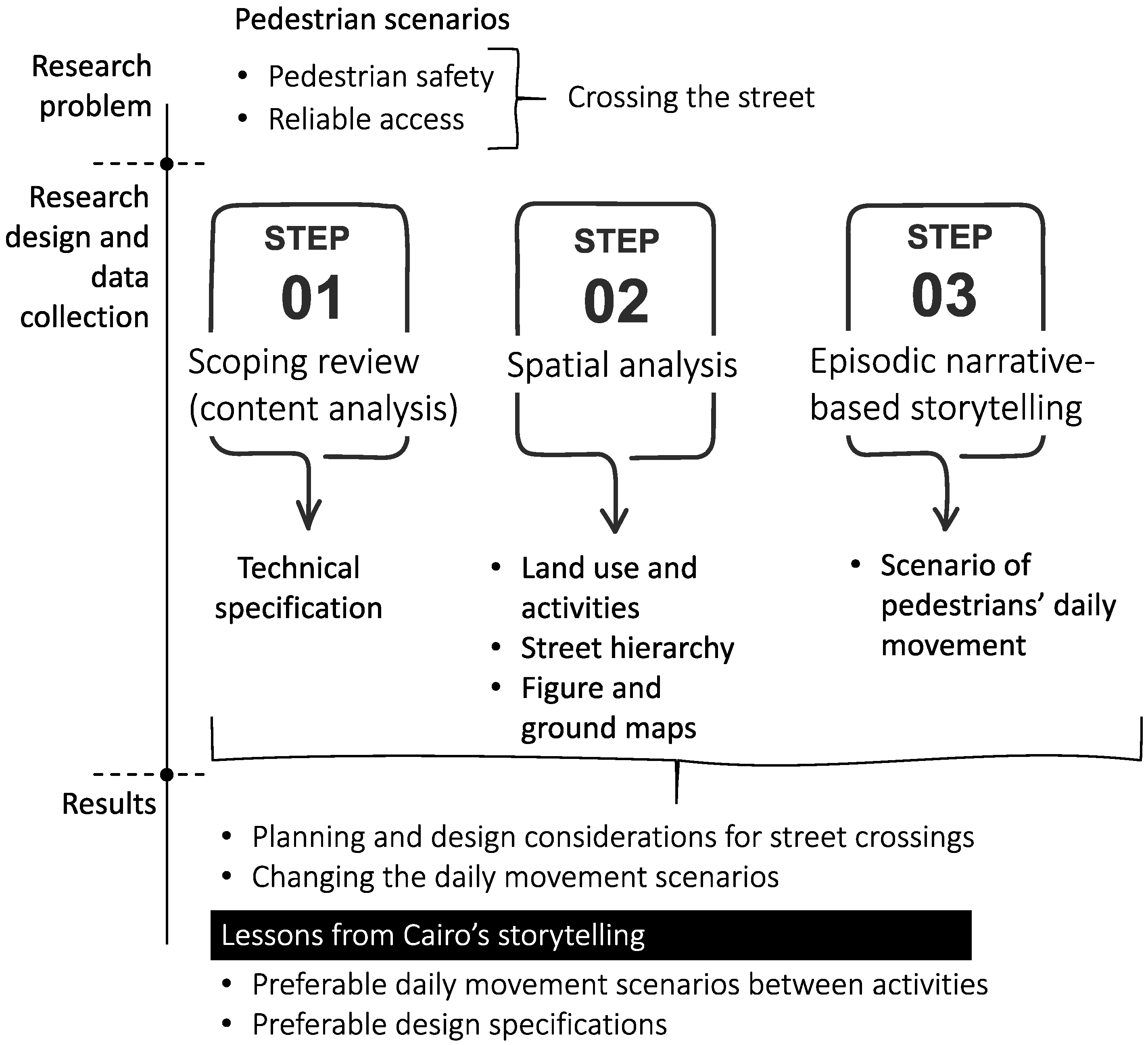

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

- This study area includes two well-known streets among Cairo residents: El-Sayed El-Merghany Street and Ahmed Tayseer Street. Both streets show how the city has changed in terms of its urban form and layout. They also reflect the constant changes in daily pedestrian movement scenarios;

- The researchers have frequently visited this site for over twenty-five years, and have lived there for more than fifteen years;

- Since the 1970s, the site has undergone several functional changes.

2.2. Research Design and Data Collection

- A theoretical set of assessment criteria for the improvements of old city streets, focusing on pedestrian safety and reliable access. This set considers pedestrians’ preferences in real-life situations when moving from one activity to another;

- The visualized changes made to urban streets, using internet-based aerial maps (hierarchy, number of lanes, sidewalks, parking lots, and pedestrian crossing areas), which information was verified through frequent field visits;

- Cairenes’ stories of daily scenarios of movement between activities before and after the changes made to the urban streets of Ard el Golf in Heliopolis (Figure 3).

2.3. Participants

- More than ten years spent living in Ard el Golf;

- Represented a variety of races, classes, and beliefs;

- Showed intellectual and psychological differences to the point of dissonance and divergence;

- Showed excellent leadership, control, initiative, and decision-making skills;

- Took chances to undergo a few different trips.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Scoping Review: Urban Street Improvement

3.1.1. Street Design and Technical Specifications

- Improve the city’s internal street network to meet the requirements of the hierarchy, and ensure safe and active traffic, without modifying the specifications of specific roads to make them into arterial roads or collection routes, and without sacrificing their pedestrian-friendliness (Levinson and Zhu 2012);

- Promote safe and appropriate speeds for pedestrians with horizontal traffic calming, speed bumps, or cushions (Macdonald et al. 2018);

- The addressing of safety issues affecting pedestrians, cars, and trams by slowing down cars and giving pedestrians the right of way (Rychlewski 2016);

- Designing paths that are more “walkable” as regards distance, time, and effort, and crossings that are safer for pedestrians who must follow divergent routes and cross streets to reach their destination (D’Acci 2019; Rychlewski 2016). Pedestrian crossings with traffic lights should be no more than 20 min apart (Anciaes and Jones 2018);

- The viewing distances of drivers and pedestrians should be extended (Montella et al. 2022; Rychlewski 2016), and the placement of street furniture, benches, planters, and trees should be improved (Macdonald et al. 2018), to provide safer pedestrian crossings;

- The ease of walking (walkability) and accessibility to amenities should be taken as primary principles (Frank et al. 2019);

- Sidewalks are essential for pedestrians, and other uses (e.g., car parks or additional spaces for shops) should be restricted on sidewalks, in favor of restaurants and street vendors. Fixed and movable barriers help in keeping sidewalks open for pedestrians, and ensure streets are safe and accessible (Frank et al. 2019).

3.1.2. Site Planning for Daily Scenarios between Activities

- The transformation of the urban street network, the urbanization of land, and preferences for use, focusing on the role of sociability and its effects on daily rhythms, are essential components that must be examined, along with the rapid and unpredictable changes accompanying them (Brookfield 2017);

- The different scenarios of daily movement undertaken by residents and visitors should be mapped to show how these daily scenarios change with successive urban street improvement projects (Erturan and Spek 2022);

- Considerations of typology, accessibility, and functionality should contribute to the development of the urban form (and the hierarchical ordering of activities should always be refined in relation to activities preferred in different seasons) (Xia et al. 2022);

- Adding new opportunities for activity, improving the quality of services, and increasing opportunities to experience the pleasant, peaceful, quiet, historical, socially connected, and memorable aspects of a place help create vibrant urban streets (Moura et al. 2017);

- Spaces should be designed to facilitate playful experiences that allow pedestrian participation and avoid the development of an impersonal, stressful, and frustrating environment (Smith 2023);

- The best way for people to have different social experiences is to gradually transition spaces from public to private (Thwaites et al. 2020);

- Mixes of personal and commercial users, such as street vendors, should be organized along the street to meet the needs of all groups. This arrangement will make pedestrians feel safer and more comfortable (Thomas and Bertolini 2022);

- Long-term plans for projects that will improve urban streets must consider and adhere to the arrangement of activities on urban streets (Bertolini 2020).

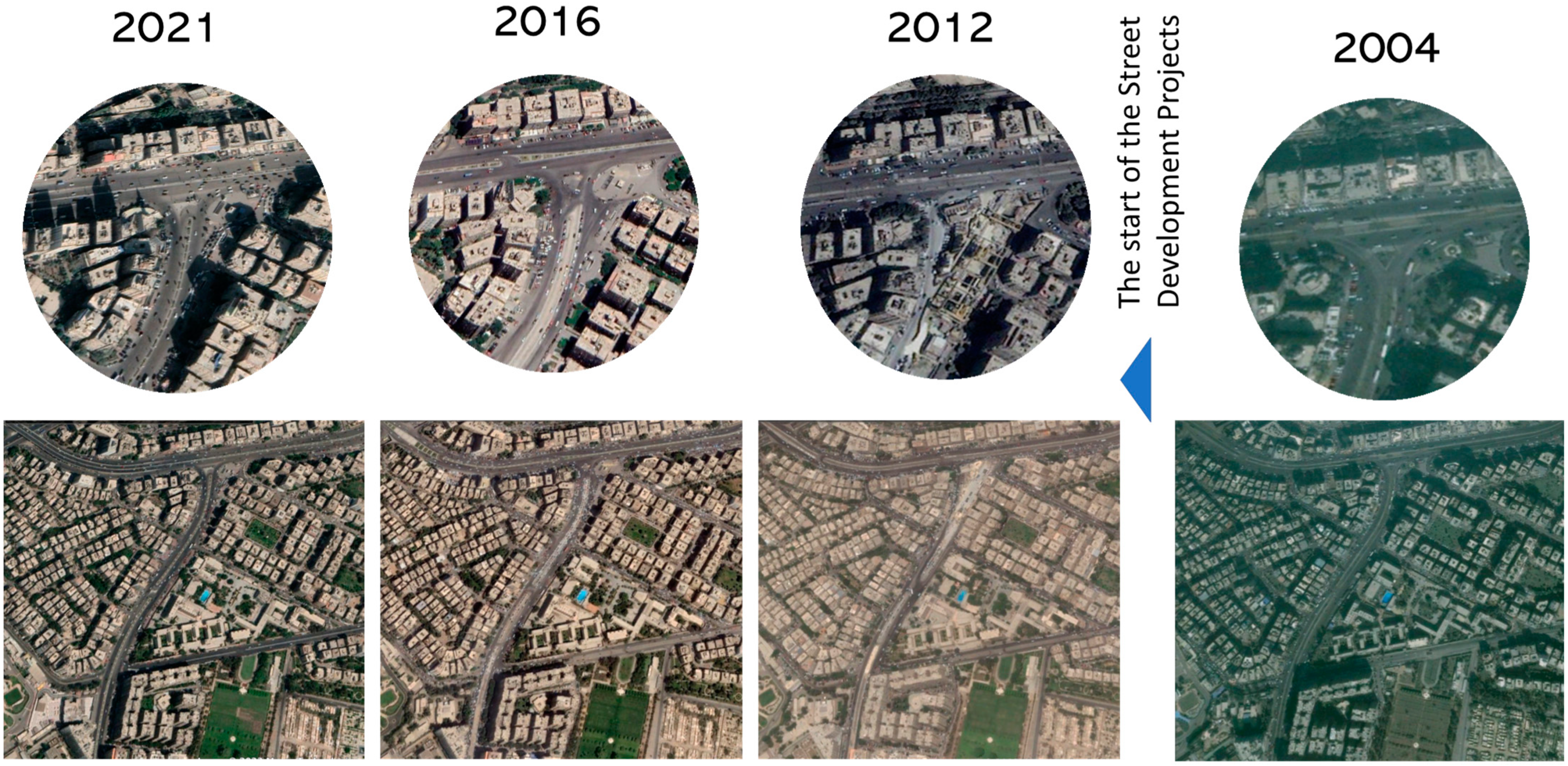

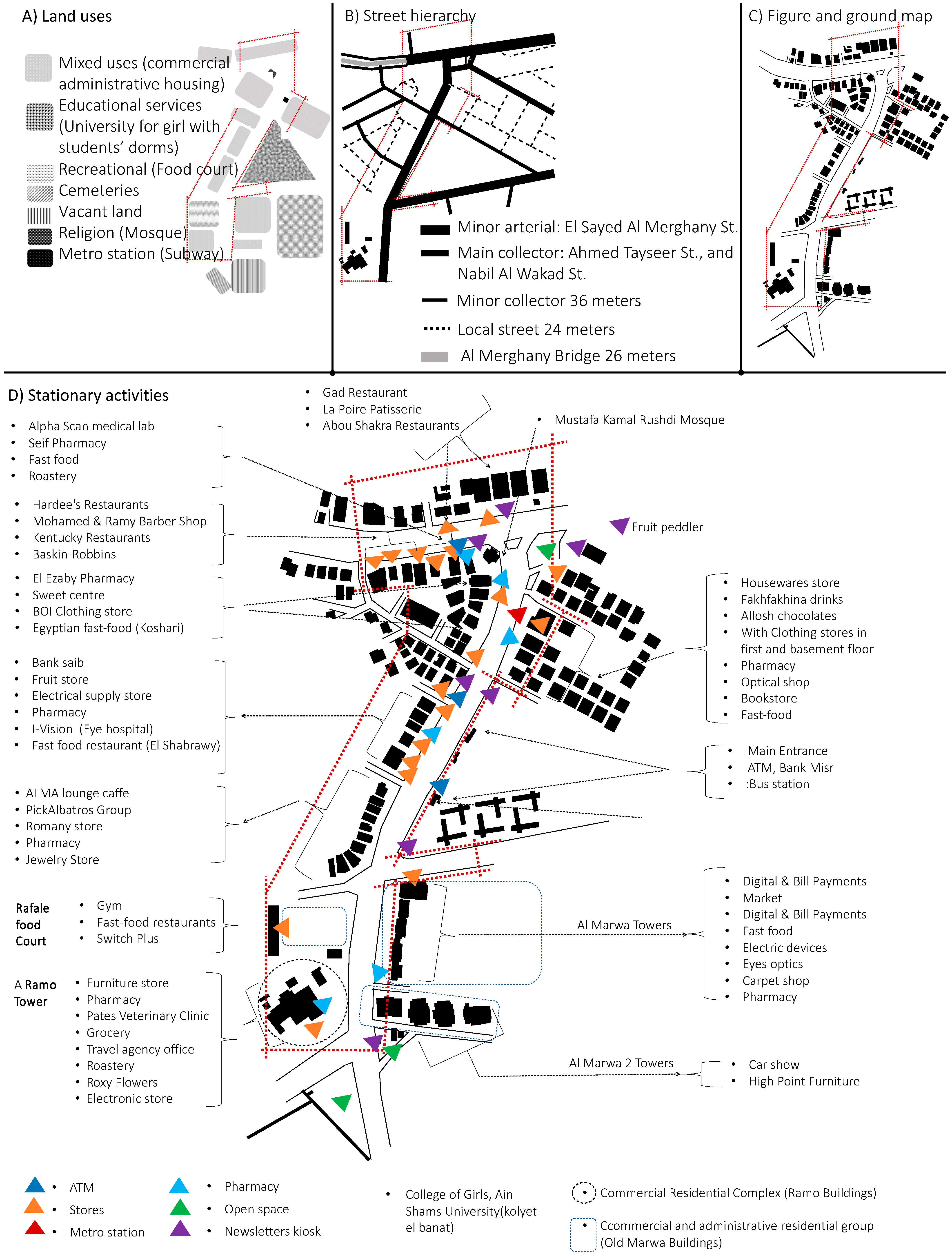

3.2. Results from the Spatial Analysis: Urban Streets with the Chronology of the Changes

3.2.1. A Timeline of the Study Area’s Spatial Changes between 2012 and 2022

3.2.2. An Illustration of the Status Quo in 2022

3.3. Storytelling Ideas: Episodic Narrative Interviews

3.3.1. Street Design and Technical Considerations for Street Crossings

A third university student in Cairo smiled while stating, “When I cross the street, I do not wait for cars to slow down before moving forward. Suppose the driver sees how brave and determined you are to cross. In that case, he will slow down […] if you ask about my preferences. We need shorter, safer pedestrian crossings to improve viewing distances for drivers and pedestrians.”

“In the past, crossing the street from anywhere was familiar, but a fast car struck me while I was crossing. To cross the street now, I must walk to the end of the street. […] You can find islands that make it easier to get across. They must slow down whenever a driver sees someone crossing at these points.” His wife, a woman in her 40s working as an architect at the same firm, said, “In fact, developers strive to provide pedestrian safety and comfort.”

“Before street improvement, the sidewalks were narrow; moving on foot was impossible […] now, walking on the sidewalk is still challenging because some visitors believe these sidewalks are natural extensions of car parks.”

“[…] some car owners park on the sidewalk designated for pedestrians in two rows, so the place has become crowded with car organizers charging money on top of the sidewalk.”

“Anyone who wants to walk on the street must have a guide, or they may run into the cement flower boxes in front of the shops or avoid the merchandise lined up outside the shops […] keep an eye out for a news kiosk or cigarette stand occupying the sidewalk. This chaos forces anyone to leave the wide sidewalk and walk in the middle of the street among speeding cars; also, some shop owners leave their wares on the sidewalk.”

A twenty-year-old student at the University of Architectural Design (male) said, “The improvement project made it easier to park near catering restaurants while we were sitting in the car. But, as you can see, the car situation doesn’t consider how people walking and people who work in restaurants might get in each other’s way. Most of the time, I find the worker at the juice shop almost hitting a pedestrian on the sidewalk.”

“Because of this improvement project, Ahmed Tayseer Street is now a well-known spot for Cairo residents […] the improvement project helped create a pedestrian-friendly environment by widening sidewalks, adding benches, and planting trees. This allowed people to walk around more comfortably and safely, making the area a more attractive destination for people to visit. The only remaining issue was the conflict between pedestrian movement and car parking.”

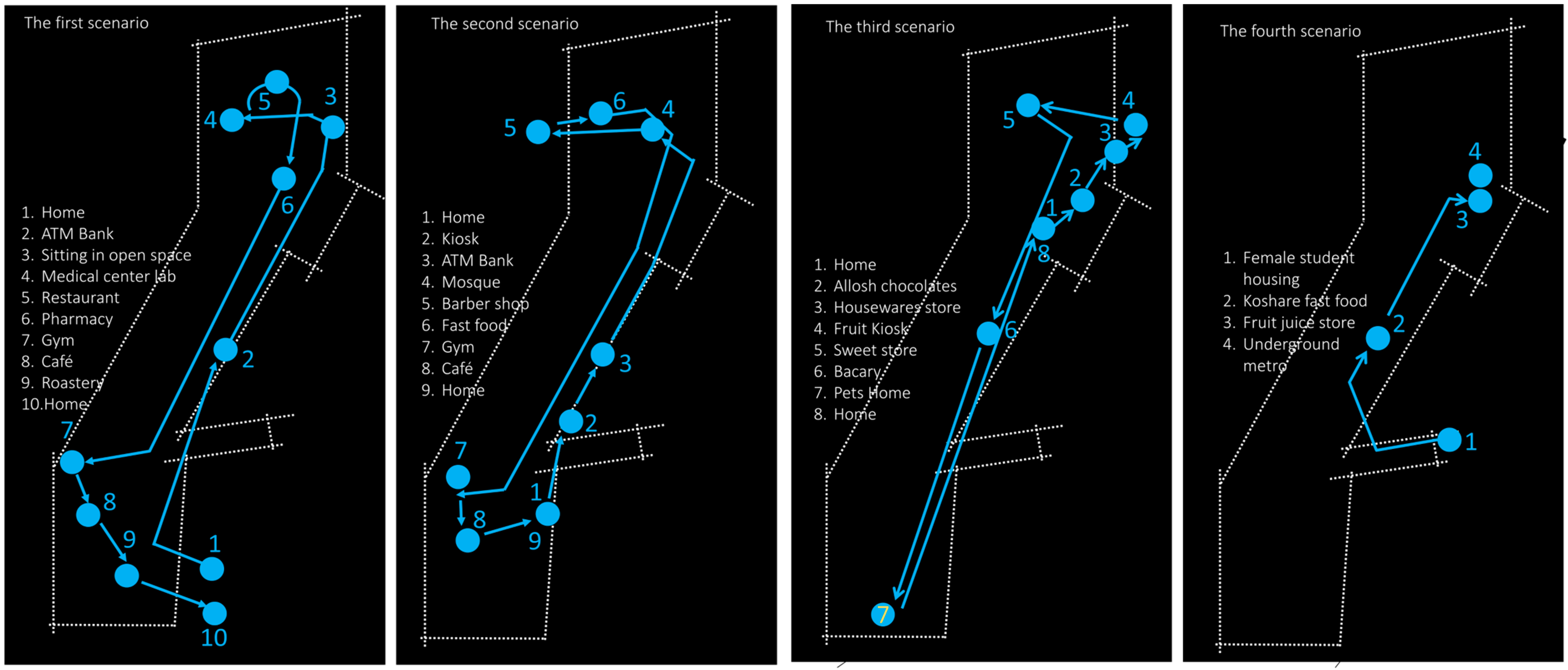

3.3.2. Changing Daily Pedestrian Movement Scenarios

“Rafale Food Court offers a variety of activities that people of all ages can enjoy, such as restaurants, cafes, and recreational facilities […] the surrounding residential buildings and recreational facilities provide a particular scenario for those interested in entertainment.”

“I am a resident of the area. Urban street improvement projects led to new activities in Ahmed Tayseer Street, such as a roaster, a pet home, dry cleaners, hairdressers for women, and international brand ready-to-wear shops.”

An accountant at an investment company in his 30s commented, “Establishing restaurants under flyovers, after developing a network of traffic, is a smart decision […] These activities changed daily pedestrian movement scenarios.”

“The problem is that the new building should have considered the history and grandeur of Merghany Street […] because of the similarities in the bridges and under the bridges, it is impossible to distinguish the areas on the street.”

“People who make decisions should talk to development experts about the place’s identity and character. This consultation will help ensure that the needs and points of view of the local community are considered when making decisions […] it ensures that improvement projects work according to the area’s specific needs and align with local culture.”

3.3.3. Four Different Everyday Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. An Action Plan for Urban Streets Improvement in Old-Built Environments

- Identify the exact site of the improvement project.

- Develop urban street design standards and classifications (functions, hierarchy, widths, number of lanes, speed, and walkways).

- Propose varieties and multiple activities and reorder and organize them according to expected movement scenarios (activity relationships, diversity, and business/leisure trips).

- Determine safe pedestrian crossing points by reviewing the technical specifications for the urban street network.

- Redetermine pedestrian crossing locations based on technical specifications.

- Provide suggestions for improving pedestrian crossings based on daily scenarios between activities.

4.2. Guideline-Based Assessment Principles and Criteria

- Group one: Technical specifications for pedestrians crossing streets safely

- Understanding and memorizing urban street hierarchy: In the old district, the encounter between collector and local streets remains unchanged. This concern is because collector streets provide the main access points for people living in the city. In contrast, the local streets are used to access individual buildings directly. This hierarchy of streets remains the same, even in older districts, as it provides the most efficient way to navigate the city.

- Parking space availability should be designed for collector streets and local urban streets. The relationship between them should allow easy access and safe and effective movement, ensure traffic flows evenly, and prevent congestion. This interconnected relationship reduces on-street parking, allowing more space for pedestrians and cyclists. It also should efficiently serve buildings, residential, commercial, and recreational activities, and pedestrian crossing points.

- Giving pedestrians the right of way: Encouraging drivers to yield to pedestrians to prevent accidents, making walking a more attractive option to reduce congestion on the roads, and creating a sense of community and connection between pedestrians and drivers, which can lead to a safer and more enjoyable experience for everyone.

- Prioritizing pedestrian-friendly infrastructure: Sidewalks are essential for pedestrians and should prevent non-pedestrians from using sidewalks as car parks or additional spaces for shops, restaurants, and street vendors. Fixed and moving barriers help keep sidewalks open for pedestrians and ensure streets are safe and accessible. Improved street lighting increases visibility to reduce accidents.

- Creating increased visibility of pedestrian crossings: Slowing pedestrian speeds and making them more appropriate through viewing distances for drivers and pedestrians and a better design of available spaces for street furniture, benches, planters, and street trees should be used to provide safer pedestrian crossings.

- Traffic-calming measures reduce traffic speed and motor-vehicle collisions, making roads more inviting for pedestrians and cyclists. The measures include horizontal and vertical speed bumps, chicanes, roundabouts, cushions, and speed tables. It also includes traffic circles, raised and textured crosswalks, illuminated signs, and other visual cues to remind drivers to slow down. They also provide physical barriers such as bollards that separate pedestrians and cyclists from traffic.

- Traffic lights and pedestrian signals: Traffic lights and pedestrian signals inform pedestrians when to cross a road. Most pedestrian signals are designed to ensure orderly traffic flow, allow pedestrians or vehicles to pass through an intersection, and reduce accident risk. Moreover, they reduce the waiting time at an intersection for cars and pedestrians. It should take at least 21 min between pedestrian crossings and traffic lights. This situation ensures that pedestrians have enough time to cross the road safely before the traffic lights turn green and to prevent delays in traffic flow.

- Group two: Site planning for daily scenarios between activities

- Diversity of activities: This measure measures people’s ability to fulfill all their daily needs from one side of urban streets by repeating similar activities. For instance, cities with dense street networks often have grocery stores, restaurants, and other services within walking distance.

- Activities are rearranged according to their functions and use in separate urban streets. They should also be compatible with each other and other activities in public spaces, such as fixed kiosks selling snacks and street vendors.

- Create multiple scenarios for daily movement between activities with an updated arrangement of compatible activities. These scenarios consider people’s preferences and adapt to crossing urban streets, traffic-calming, traffic lights, and pedestrian signals.

- Enhancing pedestrian engagement: By understanding and analyzing people’s accounts of movement scenarios according to spatial and temporal contexts, as well as different cultures, lifestyles, conditions, and economic capabilities.

- Balancing all groups’ needs with long-term plans: This measure requires careful and strategic planning to ensure continuous and balanced consequences of urban street improvements for all stakeholders over time. It considers the needs of pedestrians, cyclists, drivers, public transportation users, and other groups in the community. Creating an action plan that meets all stakeholders’ needs is the goal of each improvement project.

4.3. Research Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2018. Knowledge-based urban design in the architectural academic field. In Knowledge-Based Urban Development in the Middle East. Edited by Ali A. Alraouf. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 204–27. [Google Scholar]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2020. Urban design assessment tools: A model for exploring atmospheres and situations. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Urban Design and Planning 173: 238–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2021. Improving visitor satisfaction in Egypt’s Heliopolis historical district. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science 68: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2022. Notes on Developing Research Review in Urban Planning and Urban Design Based on PRISMA Statement. Social Sciences 11: 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Tufail, Mehdi Moeinaddini, Meshal Almoshaogeh, Arshad Jamal, Imran Nawaz, and Fawaz Alharbi. 2021. A new pedestrian crossing level of service (PCLOS) method for promoting safe pedestrian crossing in urban areas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anapali, Iliani Styliani, Socrates Basbas, and Andreas Nikiforiadis. 2021. Pedestrians’ Crossing Dilemma during the First Seconds of the Red-Light Phase. Social Sciences 10: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anciaes, Paulo Rui, and Peter Jones. 2018. Estimating preferences for different types of pedestrian crossing facilities. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 25: 222–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avineri, Erel, David Shinar, and Yusak O. Susilo. 2012. Pedestrians’ behaviour in cross walks: The effects of fear of falling and age. Accident Analysis & Prevention 44: 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, Luca. 2020. From “streets for traffic” to “streets for people”: Can street experiments transform urban mobility? Transport Reviews 40: 734–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, Katherine. 2017. Residents’ preferences for walkable neighbourhoods. Journal of Urban Design 22: 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acci, Luca. 2019. Aesthetical cognitive perceptions of urban street form. Pedestrian preferences towards straight or curvy route shapes. Journal of Urban Design 24: 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, Mercy, Mark Zuidgeest, and Stephane Hess. 2019. Modelling pedestrian crossing choice on Cape Town’s freeways: Caught between a rock and a hard place? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 60: 245–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldaidamony, Muhammad, Ahmed A. A. Shetawy, Yehya Serag, and Abeer Elshater. 2019. Applying the Gentrification Indicators in Heliopolis District. In Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation. Edited by Dean Hawkes, Hocine Bougdah, Federica Rosso, Nicola Cavalagli, Mahmoud Yousef M. Ghoneem, Chaham Alalouch and Nabil Mohareb. Cham: Springer, pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kadi, Abdul-Wahab. 2013. Suggested solutions for traffic congestion in Greater Cairo. Journal of Sustainable Development 6: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, Abeer, and Hisham Abusaada. 2022. Developing process for selecting research techniques in urban planning and urban design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review. Social Sciences 11: 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, Abeer, Hisham Abusaada, Abdulmoneim Alfiky, Nardine El-Bardisy, Esraa Elmarakby, and Sandy Grant. 2022a. Workers’ satisfaction vis-à-vis environmental and socio-morphological aspects for sustainability and decent work. Sustainability 14: 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, Abeer, Hisham Abusaada, Menna Tarek, and Samy Afifi. 2022b. Designing the Socio-Spatial Context Urban Infill, Liveability, and Conviviality. Built Environment 48: 341–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, Abeer. 2016. The ten-minute neighborhood is [not] a basic planning unit for happiness in Egypt. Archnet-IJAR 10: 344–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, Abeer. 2020. Food consumption in the everyday life of liveable cities: Design implications for conviviality. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 13: 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturan, Arzu, and Stefan Christiaan van der Spek. 2022. Walkability analyses of Delft city centre by Go-Along walks and testing of different design scenarios for a more walkable environment. Journal of Urban Design 27: 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, Joshua, Friederike E. L. Otto, and E. Lisa F. Schipperr. 2021. Storytelling can be a powerful tool for science. Nature 589: 352–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmanowicz, Stephen, ed. 2008. Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU): CNU Charter Awards Jury. Pittsburgh: Wolfe Design, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Lawrence D., Nicole Iroz-Elardo, Kara E. MacLeod, and Andy Hong. 2019. Pathways from built environment to health: A conceptual framework linking behavior and exposure-based impacts. Journal of Transport & Health 12: 319–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerike, Regine, Caroline Koszowski, Bettina Schröter, Ralph Buehler, Paul Schepers, Johannes Weber, Rico Wittwer, and Peter Jones. 2021. Built environment determinants of pedestrian activities and their consideration in urban street design. Sustainability 13: 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman, Philippe. 2015. Negotiation and social transactions in urban policies: The case of the tramway projects in France. Urban Research & Practice 8: 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, Robin, and Katy Huaylla Sallo. 2022. The political economy of streetspace reallocation projects: Aldgate Square and Bank Junction, London. Journal of Urban Design 27: 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulst, Merlijn van. 2012. Storytelling, a model of and a model for planning. Planning Theory 11: 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, David, and Shanjiang Zhu. 2012. The hierarchy of roads, the locality of traffic, and governance. Transport Policy 19: 147–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Patrick John, and Katia Hildebrandt. 2019. Storytelling as qualitative research. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug and Richard A. Williams. London: SAGE Publications Limited, pp. 161–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, Elizabeth, Nicola Szibbo, William Eisenstein, and Louise Mozingo. 2018. Quality-of-service: Toward a standardized rating tool for pedestrian quality of urban streets. Journal of Urban Design 23: 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, Rabi Narayan, and Prabhjot Singh Chani. 2022. Assessment of pedestrians’ travel experience at the religious city of Puri using structural equation modelling. Journal of Urban Design 25: 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monazzam, Mohammad R., Vahideh Abolhasannejad, Bibi Narjes Moasheri, Vahid Abolhasannejad, and Hamid Kardanmoghaddam. 2016. Noise pollution in old and new urban fabric with focus on traffic flow. Journal of Low Frequency Noise Vibration and Active Control 35: 257–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, Alfonso, Salvatore Chiaradonna, Alessandro Claudi de Saint Mihiel, Gord Lovegrove, Pietro Nunziante, and Maria Rella Riccardi. 2022. Sustainable complete streets design criteria and case study in Naples, Italy. Sustainability 14: 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, Hanaa. 2022. Conserving heritage railways and tramways in Egypt. International Design Journal 12: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, Filipe, Paulo Cambra, and Alexandre Bacelar Gonçalves. 2017. Measuring walkability for distinct pedestrian groups with a participatory assessment method: A case study in Lisbon. Landscape and Urban Planning 157: 282–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Jin, Caterina Villani, and Gianni Talamini. 2021. The capital value of pedestrianization in Asia’s commercial cityscape: Evidence from office towers and retail streets. Transport Policy 107: 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC). 2019. Navigating New Mobility: Policy Approaches for Cities. Eugene: University of Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, Dilek, and İrem Selçuk. 2017. From pedestrianisation to commercial gentrification: The case of Kadıköy in Istanbul. Cities 65: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prytherch, David L. 2021. Reimagining the physical/social infrastructure of the American street: Policy and design for mobility justice and conviviality. Urban Geography 43: 688–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychlewski, Jeremi. 2016. Street network design for a sustainable mobility system. Transportation Research Procedia 14: 528–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, Leonie. 2003. Out of the closet: The importance of stories and storytelling in planning practice. Planning Theory & Practice 4: 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, Nargis, Yasser Mansour, Shaimaa Kamel, and Ruby Morcos. 2021. The impact of the Cairo streets development project on the independent mobility of children: A field study on the streets of Heliopolis, Egypt. Infrastructure 6: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Carl A. 2023. Community drawing and storytelling to understand the place experience of walking and cycling in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. Land 12: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Ren, and Luca Bertolini. 2022. Transit-Oriented Development: Learning from International Case Studies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Switzerland AG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, Kevin, James Simpson, and Ian Simkins. 2020. Transitional edges: A conceptual framework for socio-spatial understanding of urban street edges. Urban Design International 25: 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanumu, Lakshmi Devi, K. Ramachandra Rao, and Geetam Tiwari. 2017. Fundamental diagrams of pedestrian flow characteristics: A review. European Transport Research Review 9: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, Caterina, and Gianni Talamini. 2021. Pedestrianised streets in the global neoliberal city: A battleground between hegemonic strategies of commodification and informal tactics of commoning. Cities 108: 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schönfeld, Kim Carlotta, and Luca Bertolini. 2017. Urban streets: Epitomes of planning challenges and opportunities at the interface of public space and mobility. Cities 68: 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wael, Shereen, Abeer Elshater, and Samy Afifi. 2022. Mapping user experiences around transit stops using computer vision technology: Action priorities from Cairo. Sustainability 14: 11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2013. Global Status Report on Road Safety. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Chang, Anqi Zhang, and Anthony G. O. Yeh. 2022. The varying relationships between multidimensional urban form and urban vitality in Chinese megacities: Insights from a comparative analysis. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112: 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Xinyue, Jiaxin Du, Yu Han, Galen Newman, David Retchless, Lei Zou, Youngjib Ham, and Zhenhang Cai. 2022. Developing Human-Centered Urban Digital Twins for Community Infrastructure Resilience: A Research Agenda. Journal of Planning Literature 38: 187–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeer, Charles V., Laura Sandt, and Margaret Scully. 2006. How to Develop a Pedestrian Safety Action Plan. Chapel Hill: Highway Safety Research Center, University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Cairenes’ Storytelling: Pedestrian Scenarios as a Normative Factor When Enforcing Street Changes in Residential Areas. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050278

Abusaada H, Elshater A. Cairenes’ Storytelling: Pedestrian Scenarios as a Normative Factor When Enforcing Street Changes in Residential Areas. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(5):278. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050278

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2023. "Cairenes’ Storytelling: Pedestrian Scenarios as a Normative Factor When Enforcing Street Changes in Residential Areas" Social Sciences 12, no. 5: 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050278

APA StyleAbusaada, H., & Elshater, A. (2023). Cairenes’ Storytelling: Pedestrian Scenarios as a Normative Factor When Enforcing Street Changes in Residential Areas. Social Sciences, 12(5), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050278