Teleworking and Job Quality in Latin American Countries: A Comparison from an Impact Approach in 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Teleworking and Its Relationship with Job Quality

2.1. Teleworking and Job Quality

2.2. Potential Relationship between Teleworking and Job Quality

When organized and carried out properly, telework can be beneficial for mental health and social well-being. It can improve work–life balance, reduce time spent on commuting to the workplace, and offer opportunities for flexible work arrangements, all of which may promote mental health and social wellbeing.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials: Data

3.2. Job Quality Index Methodology

3.3. Impact Evaluation Methodology

- : average differences of the treatment on the treated (ATT)

- : average or mathematical expectation

- : potential outcomes (level of each job quality component)

- : group, denoted 1 for treatment and 2 for control.

4. Results

4.1. Average Comparison (Descriptive Analysis)

4.2. Job Quality Index Results

4.3. Impact Evaluation Results

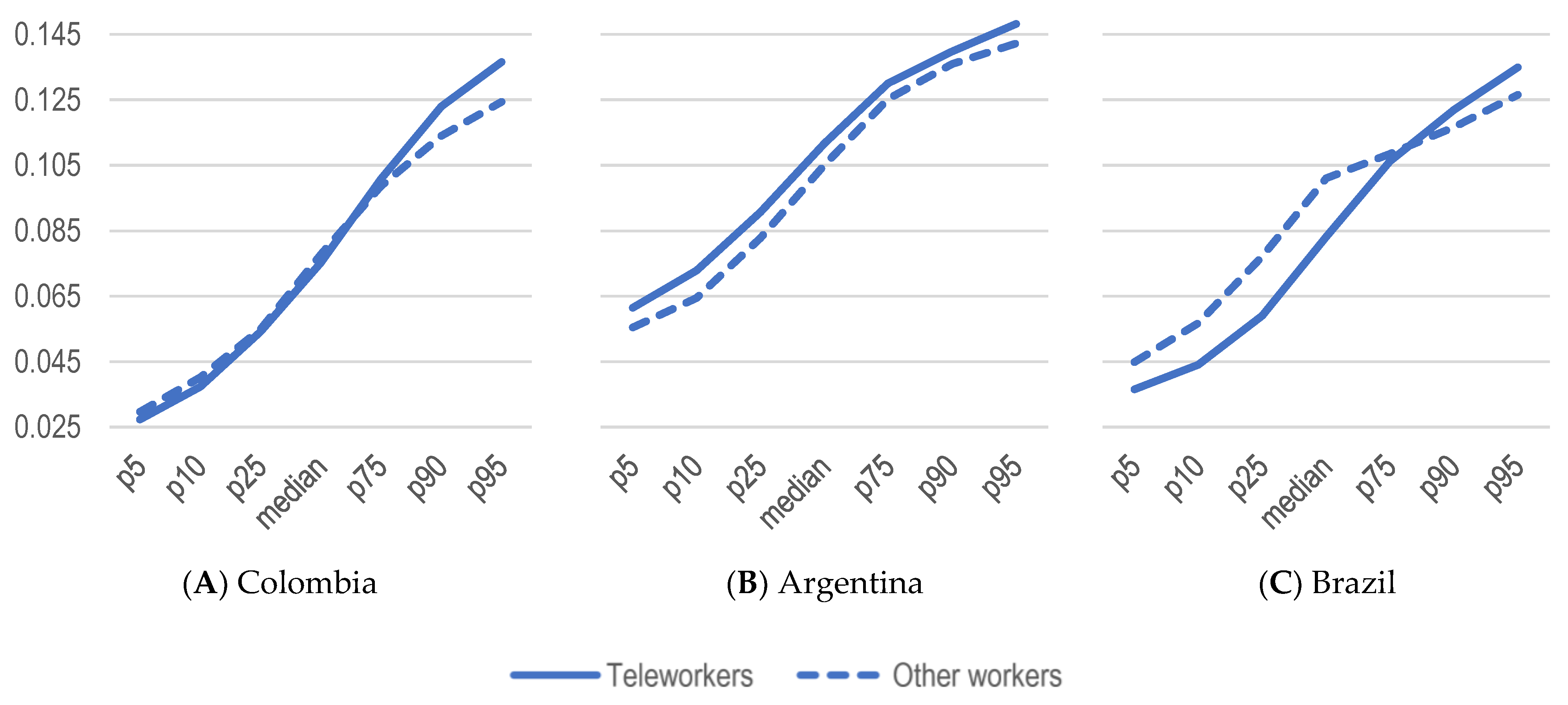

4.3.1. Labor Income

4.3.2. Social Security Coverage

4.3.3. Job Stability

4.3.4. Workday

4.3.5. Job Quality Index

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- (i)

- They receive higher income in Colombia (21.8%) and Argentina (13.5%).

- (ii)

- They have less social security coverage in Brazil (−15.9 p.p.) and Colombia (−3.2 p.p.).

- (iii)

- They have approximately the same job stability.

- (iv)

- They work less hours per week in Brazil (−5.9 h), Argentina (−5.0 h), and Colombia (−1.0 h), which is positive for Brazil and Colombia, where the average working day is close to the official one, but may be negative for Argentina, where there is a deficit of hours worked.

- (v)

- They exhibit a job quality index with lower average values in Brazil (−11.9%), while Colombia and Argentina present analytically equal values to other comparable workers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Some interesting studies in this regard are Azarbouyeh and Naini (2014) and Rodríguez-Modroño and López-Igual (2021). Azarbouyeh and Naini (2014) found that teleworking has a significant positive relationship with the components of quality of work life; this affected all types of workers in a similar way. However, Rodríguez-Modroño and López-Igual (2021) found that job quality among teleworkers varies according to the intensity of ICT use, gender, and type of employment. |

| 2 | Own translation. |

| 3 | https://www.argentina.gob.ar/trabajo/teletrabajo-0/teletrabajo-y-contrato-de-teletrabajo—Own translation, accessed on 10 March 2023. Teleworking in Argentina is regulated by (Law 27555 2020) that stipulates the contractual conditions that must be met, working hours, rights and duties, training, benefits, among others. |

| 4 | Own translation. The regulation of teleworking in Brazil is found mainly in the (Law 13467 2017). |

| 5 | The dimensions are safety and ethics of employment, income, and benefits from employment, working time and work-life balance, security of employment and social protection, social dialogue, skills development and training, and employment-related relationships and work motivation. |

| 6 | The elements are employment opportunities, adequate earnings and productive work, decent working time, combining work, family, and personal life, work that should be abolished, stability and security of work, equal opportunity and treatment in employment, safe work environment, social security, and social dialogue, employers’, and workers’ representation. Consequently, this approach to job quality is focused on monitoring aggregated decent work at the country level. |

| 7 | The databases are openly available at: https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Institucional-Indec-BasesDeDatos-1 (Argentina); https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9173-pesquisa-nacional-por-amostra-de-domicilios-continua-trimestral.html?t=microdados (Brazil); https://microdatos.dane.gov.co/index.php/catalog/701/get-microdata (Colombia). |

| 8 | This was to achieve comparability with Argentina, whose survey is limited to urban areas. |

| 9 | For Brazil, the first three quarters of the year are considered, since an error was detected in education variables in the fourth quarter that was reported to the Brazilian Statistics Institute. However, the available databases are robust enough to run the analysis on them. |

| 10 | The software used for the calculations was Stata 17 SE. |

| 11 | This is entered in a logit model that feeds the matching method used—in this case, “nearest neighbor”, which consists of selecting for each individual in the “treatment” group five “control” individuals with the closest propensity score. |

| 12 | According to the literature review, this study takes the definition of teleworkers as those who practice “the use of ICT—such as smartphones, tablets, laptops and desktop computers—for the purposes of work outside the employer’s premises” (MarcadorDePosición3) Page 5, and it is measured according to (Oviedo-Gil and Cala 2022). According to estimates, in 2021, 6.6% of all urban workers were teleworkers in Colombia, 8.4% in Argentina, and 5.5% in Brazil. |

| 13 | The variables are defined as follows: (i) labor income corresponds to the aggregation of income created by each national statistical institute; (ii) social security is a variable that indicates whether or not a worker is contributing to the pension system; (iii) length of employment indicates how long a worker has been in their current position (less than 1 month, 1 month to 1 year, more than 1 year to 5 years, or 5 years or more); and (iv) workday is the number of hours worked per week. |

| 14 | Number of observations 197,926; LR chi2(11) 12091.22; Prob > chi2 0.000; Pseudo R2 0.1114. |

| 15 | Number of observations 62,569; LR chi2(11) 3231.99; Prob > chi2 0.000; Pseudo R2 0.1328. |

| 16 | Number of observations 266,568; LR chi2(11) 18725.70; Prob > chi2 0.000; Pseudo R2 0.1505. |

| 17 | The maximum working day allowed in Argentina and Colombia is 48 h per week, while in Brazil it is 44 h per week. |

References

- Afonso, Pedro, Miguel Fonseca, and Tomás Teodoro. 2022. Evaluation of anxiety, depression and sleep quality in full-time teleworkers. Journal of Public Health 44: 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amigoni, Michael, and Sandra Gurvis. 2009. Managing the Telecommuting Employee: Set Goals, Monitor Progress, and Maximize Profit and Productivity. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Kathryn H., John S. Butler, and Frank A. Sloan. 1987. Labor Market Segmentation: A Cluster Analysis of Job Groupings and Barriers to Entry. Southern Economic Journal 53: 571–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, Evelise Dias, Leonardo Rodrigues Thomaz Bridi, Marta Santos, and Frida Marina Fischer. 2022. Part-time or full-time teleworking? A systematic review of the psychosocial risk factors of telework from home. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakaki, Agustín. 2017. Movilidad ocupacional en un mercado de trabajo segmentado: Argentina, 2003–2013. Estudios del Trabajo 54: 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Aranzazu, Diego A., Berardo J. Rodríguez, Margarita M. Zapata, John Bustamante, and Luís F. Restrepo. 2007. Aplicación del análisis de factor de correspondencia múltiple en un estudio de válvulas cardíacas en porcinos. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias 20: 129–40. [Google Scholar]

- Azarbouyeh, Amir, and Seyed Gholamreza Jalali Naini. 2014. A study on the effect of teleworking on quality of work life. Management Science Letters 4: 1063–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, Susan. 1999. Servicing the Media: Freelancing, Teleworking and ‘enterprising’ careers. New Technology, Work and Employment 14: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsadi, Otavio Valentim. 2007. Qualidade do emprego na agricultura brasileira no período 2001–2004 e suas diferenciações por culturas. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural 45: 409–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Yehuda. 2001. The Status of Research on Teleworking and an Agenda for Future Research. International Journal of Management Reviews 3: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Yehuda, and Nigel Nicholson. 1997. Home, Sweet Work: Requirement for effective home-working. Journal of General Managment 23: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjumea-Arias, Martha Luz, Eliana María Villa-Enciso, and Jackeline Valencia-Arias. 2016. Beneficios e impactos del teletrabajo en el talento humano. resultados desde una revisión de literatura. Revista CEA 2: 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, Raphael, Michael Chang, Kevin Wei Wang, and Tianwen Yu. 2020. A Blueprint for Remote Working: Lessons from China. New York: McKinsey Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying. 2015. Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130: 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, Diego, and Nicolás Sacco. 2016. El análisis de la calidad del empleo a partir de un índice multidimensional: Una mirada al mercado de trabajo urbano en Argentina (2003 y 2015). De Prácticas y Discursos: Cuadernos de Ciencias Sociales 5: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, Francois. 1979. Pobreza y Dualismo en el Sector Urbano de las Economías en Desarrollo: El Caso de Colombia. Desarrollo y Sociedad 1: 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, Francisco. 2018. Los millennials están enojados con las empresas y decepcionados con sus trabajos y la economía. Infobae. Available online: https://www.infobae.com/economia/finanzas-y-negocios/2018/05/21/los-millennials-estan-enojados-con-las-empresas-y-decepcionados-con-sus-trabajos-y-la-economia/ (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Caillier, James Gerard. 2012. The Impact of Teleworking on Work Motivation in a U.S. Federal Government Agency. American Review of Public Administration 42: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, María Isabel, Migdalia Josefina Caridad Faria, John Anderson Virviescas Peña, and Jairo Martínez. 2017. El teletrabajo como estrategia laboral competitiva en las PYME Colombianas. Espacios 38: 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cazes, Sandrine, Alexander Hijzen, and Anne Saint-Martin. 2015. Measuring and Assessing Job Quality: The OECD Job Quality Framework. In OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CENDA. 2004. Índice Global de Condiciones de Trabajo. El trabajo en la Argentina. Condiciones y Perspectivas. Buenos Aires: CENDA. [Google Scholar]

- Cetrulo, Armanda, Dario Guarascio, and Maria Enrica Virgillito. 2022. Working from home and the explosion of enduring divides: Income, employment and safety risks. Economia Politica 39: 345–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costrell, Robert M. 1990. Methodology in the ‘Job Quality’ Debate. Industrial Relations 29: 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A. 2020. Teletrabalho: Origem, conceito, fundamentação legal e seus desafios. JUS. Available online: https://jus.com.br/artigos/81185/teletrabalho-origemconceito-fundamentacao-legal-e-seus-desafios (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Dalberto, Cassiano Ricardo, and Jader Fernandes Cirino. 2018. Informalidade e segmentação no mercado de trabalho brasileiro: Evidências quantílicas sob alocação endógena. Nova Economia 28: 417–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Yamile, and Lubiza Osio. 2011. Mujer, Cyberfeminismo y Teletrabajo. Compendium 13: 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, William T., and Kevin Lang. 1991. Labor Market Segmentation Theory: Reconsidering the Evidence. Dordrecht: Springer, Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Do Nascimento, Carlos Alves, Régis Borges, Irlene JoséGonçalves, and Samantha Rezende. 2008. A qualidade do emprego rural na região nordeste (2002 e 2005). Revista da ABET 7. Available online: https://periodicos.ufpb.br/index.php/abet/article/view/15236 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Eurofound. 2020. Living, Working, and COVID-19: First Findings. Dublin: Eurofound. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/es/publications/report/2020/living-working-and-covid-19-first-findings-april-2020 (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Eurofound. 2021. Working Conditions and Sustainable Work: An Analysis Using the Job Quality Framework, Challenges and Prospects in the EU Series. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound and ILO. 2019. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work. Geneva: Joint ILO–Eurofound Report. [Google Scholar]

- Farné, Stefano. 2003. Estudio sobre la Calidad del Empleo en Colombia. Perú: Oficina Internacional del Trabajo—OIT. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, Patricia, Arne L. Kalleberg, and Chris Warhurst. 2013. The challenge of job quality. Human Relations 66: 441–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G-20. 2015. G20 Leaders’ Communiqué Antalya Summit, 15–16 November 2015. Antalya. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/23729/g20-antalya-leaders-summit-communique.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Gentilin, Mariano. 2021. Pasado, presente y futuro del Teletrabajo. Reflexiones teóricas sobre un concepto de 50 años. Working Paper—Universidasd EAFIT. Medellín: Universidad EAFIT. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, Paul J., Sebastian Martinez, Patrick Premand, Laura B. Rawlings, and Christel M. J. Vermeersch. 2016. Impact Evaluation in Practice. Washington, DC: The World Bank/International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Gittleman, Maury B., and David R. Howell. 1995. Changes in the Structure and Quality of Jobs in the United States: Effects by Race and Gender, 1973–1990. ILR Review 48: 420–40. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Francis. 2009. Subjective employment insecurity around the world. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2: 343–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, Katherine, and Isabel V. Sawhill. 2020. Telecommuting Will Likely Continue Long after the Pandemic. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/04/06/telecommuting-will-likely-continue-long-after-the-pandemic/ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- IADB. 2020. The Future of Work in Latin America and The Caribbean. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 1999. ILC87—Report of the Director-General: Decent Work—ILO. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020a. 2020 Labour Overview. Latin American and Caribbean. Covid 19—Edition. Policy Brief. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_777630.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- ILO. 2020b. COVID-19: Guidance for Labour Statistics Data Collection—Defining and Measuring Remote Work, Telework, Work at Home and Home-Based Work. Technical Note. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020c. Practical Guide on Teleworking during the COVID-19 Pandemic and beyond. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2021. Working from Home: From Invisibility to Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO and WHO. 2021. Healthy and Safe Telework: Technical Brief. Geneva: World Health Organization and International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_836151/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Jaramillo, Alejandro Franco, and Félix Andrés Restrepo Bustamante. 2011. El perfil del teletrabajador y su incidencia en el éxito. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, 1–6. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1942/194218961001.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, Diana, and Natalia Páez. 2014. Una Metodología Alternativa para Medir la Calidad del Empleo en Colombia. Sociedad y Economía, 129–54. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/soec/n27/n27a06.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Jiménez, Mónica. 2011. La economía informal y el mercado laboral en la Argentina: Un análisis desde la perspectiva del Trabajo Decente. Documento de Trabajo CEDLAS N° 116. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de La Plata. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. 1957. Automation and Desing. Desing, 104–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Marcia M. 1985. Th Next Workplace Revolution: Telecommuting. Supervisory Management 30: 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kostzer, Daniel, Bárbara Perrot, Lila Schachtel, and Soledad Villafañe. 2005. Índice de fragilidad laboral: Un análisis geográfico comparado del empleo y el trabajo a partir del EPH. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Trabajo de la Nación. [Google Scholar]

- Lamond, David A., Peter Standen, and Kevin Daniels. 1998. Contexts, Cultures and Forms of Teleworking. In Management Theory and Practice: Moving to a New Era. New York: Macmillan Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Las Heras, Mireia, and María Barraza. 2019. Un lugar de trabajo sostenible: Hacia un modelo remoto y presencial. Pamplona: IESE. [Google Scholar]

- Law 1221. 2008. Por la cual se establecen normas para promover y regular el Teletrabajo y se dictan otras disposiciones. Bogotá: Congreso de la República de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Law 13467. 2017. Altera a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho. Brasilia: Congresso Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Law 27555. 2020. Régimen legal del contrato de teletrabajo. Buenos Aires: Senado y Cámara de Diputados de la Nación Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- López-Roldán, Pedro, and Sandra Fachelli. 2015. Metodología de la Investigación Social Cuantitativa. Barcelona: Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Susan R. 2011. The Benefits, Challenges, and Implications of Teleworking: A Literature Review. Culture & Religion Review Journal 2011: 148–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, William Francis. 1998. Are Labor Markets in Development Countries Dualistic? Policy Research Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Charlotte K., Mareike Reimann, and Martin Diewald. 2021. Do work–life measures really matter? The impact of flexible working hours and home-based teleworking in preventing voluntary employee exits. Social Sciences 10: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulley, Lharriet. 2020. Lockdown: Homeworkers putting in extra hours—Instant messaging up 1900%. The HR Director. April 27. Available online: https://www.thehrdirector.com/business-news/the-workplace/new-data-over-a-third-38-admit-to-working-longer-hours-when-working-from-home/ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Miglioretti, Massimo, Andrea Gragnano, Simona Margheritti, and Eleonora Picco. 2021. Not all telework is valuable. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones 37: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Rafael Munoz, Enrique Fernández-Macías, José-Ignacio Antón, and Fernando Esteve. 2011. Measuring More than Money: The Social Economics of Job Quality. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nilles, Jack. 1975. Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Transactions on Communications 23: 1142–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, Jack Michael, Frederick Carlson, Patrick Gray, and Gary Hanneman. 1976. The Telecommunications-Transportation Trade-Off. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2021. Teleworking in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Trends and Prospects. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, Ana Isabel. 2018. Factors that influence job satisfaction of teleworkers: Evidence from Mexico. Global Journal of Business Research 12: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Gil, Yanira Marcela, and Favio Cala. 2022. Dynamics of the determinants of teleworking in Latin American countries 2019–2021. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Paulo, Evânio Mascarenhas, Francisco José Silva Tabosa, Ahmad Saeed Khan, and Leonardo Andrade Rocha. 2021. La dinámica del empleo rural en el Brasil: Un análisis mediante modelos de panel dinámico. Revista CEPAL, 161–81. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, Michael J. 1975. Notes for a Theory of Labor Market Stratification. In Labor Market Segmentation. Lexington: D.C. Heath. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/64001/notesfortheoryof00pior.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Reisenwitz, Cathy. 2020. How COVID-19 is impacting workers’ calendars. Clockwise Blog. April 4. Available online: https://www.getclockwise.com/blog/how-covid-19-is-impacting-workers-calendars (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Rodríguez-Modroño, Paula, and Purificación López-Igual. 2021. Job Quality and Work—Life Balance of Teleworkers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safirova, Elena, and Margaret Walls. 2004. What Have We Learned from a Recent Survey of Teleworkers? Evaluating the 2002 SCAG Survey. In Resources for the Future—Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, (No. 1318-2016-103276) 04-43. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/10866/files/dp040043.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Sánchez, Gabriela, and Arturo Montenegro. 2019. Teletrabajo una propuesta de innovación en productividad empresarial. Dialnet 4: 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnbruch, Kirsten, Pablo González, Mauricio Apablaza, Rocío Méndez, and Verónica Arriagada. 2020. The Quality of Employment (QoE) in nine Latin American countries: A multidimensional perspective. World Development 127: 104738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Uva, Mafalda, António Sousa-Uva, and Florentino Serranheira. 2021. Telework during the COVID-19 epidemic in Portugal and determinants of job satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21: 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffgen, Georges, Philipp E. Sischka, and Martha Fernandez de Henestrosa. 2020. The Quality of Work Index and the Quality of Employment Index: A Multidimensional Approach of Job Quality and Its Links toWell-Being at Work. International Journal of Enviromental Research and Public Health 17: 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannuri-Pianto, Maria, and Donald Pianto. 2016. Mercado de trabalho informal no Brasil: Escolha ou segmentação? In Causas e consequências da informalidade no Brasil. Edited by Fernando de Holanda Barbosa Filho, Gabriel Ulyssea and Fernando A. Veloso. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Toffler, Alvin. 1980. The Thrid Wave. London: Collins. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. 2015. Handbook on Measuring Quality of Employment. New York and Geneva: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, José Ignacio, and Carlos Ortiz. 2012. Informalidad y Segmentación en el Mercado Laboral. Saarbrucken: Editoral Académica Española. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, José Ignacio, Carlos Humberto Ortiz, and Gustavo Adolfo García. 2007. La Segmentación del Mercado Laboral Colombiano en la Década de los Noventa. Revista de Economía Institucional 9: 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, José Ignacio, Javier Castro, and Carlos Ortiz. 2005. ¿Qué tan segmentado era el mercado laboral colombiano en la década de los noventa? Documentos de Trabajo CIDSE; (No. 003829). Universidad del Valle-CIDSE. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Colombia/cidse-univalle/20190621055926/doc78.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Urrea, Fernando Urrea. 2009. Reseña de “Informalidad laboral en Colombia 1988–2000. Evolución, teorías y modelos”. Sociedad y Economía 16: 195–97. [Google Scholar]

- Waisgrais, Sebastián. 2001. Segmentación del Mercado de Trabajo en Argentina: Una Aproximación a través de la Economía Informal. Asociación Argentina de Especialista en Estudios del trabajo, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, Dan. 2012. Good to be Home? Time-use and Satisfaction Levels among Home-based Teleworkers. New Technology, Work and Employment 27: 224–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöllner, Katja, and Rozália Sulíková. 2021. Teleworking and its influence on job satisfaction. Journal of Human Resources Management Research 2021: 558863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Colombia | Argentina | Brazil |

|---|---|---|

| “Teleworking. It is a way of labor organization, which consists of the performance of paid activities or provision of services using information and communication technologies—ICT—for contact between the worker and the company, without requiring the physical presence of the worker in a specific job site”2 (Law 1221 2008), article 2. | “(…) a form of remote work, in which the worker carries out his activity without the need to physically present himself at the specific company or workplace. (...) [teleworking] It is carried out using information and communication technologies (ICT) and can be carried out at the worker’s home or in other places or establishments outside the employer’s home” Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security.3 | “(…) the provision of services predominantly outside the employer’s premises, with the use of information and communication technologies that, by their nature, do not constitute external work”4 (Da Silva 2020, p. 2). |

| Colombia | Argentina | Brazil | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teleworkers | Other Workers | Difference (%) | Teleworkers | Other Workers | Difference (%) | Teleworkers | Other Workers | Difference (%) | |

| Social security | 37.4% | 44.4% | −18.5% | 59.1% | 47.8% | 19.1% | 46.7% | 68.1% | −45.7% |

| Labor income | 1,407,567 | 1,071,278 | 23.9% | 63,790 | 42,813 | 32.9% | 3226 | 2468 | 23.5% |

| Length of employment | 3.0 | 2.9 | 5.4% | 3.5 | 3.3 | 4.9% | 2.7 | 2.7 | −0.3% |

| Workday | 43.4 | 45.6 | −5.3% | 30.4 | 34.9 | −14.7% | 34.6 | 39.7 | −14.8% |

| Labor Income (Local Currency) | Covered by Social Security (%) | Length of Employment (Duration Range) | Workday (Hours per Week) | Job Quality Index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia14 | Treated | 1,272,710 | 33.2% | 3.07 | 42.8 | 0.077 | |||||

| Controls | 1,044,670 | 36.4% | 2.99 | 43.8 | 0.075 | ||||||

| Difference | 228,040 | ** | −3.2 | ** | 0.08 | ** | −1.0 | ** | 0.001 | * | |

| (%) diff | 21.8% | −9 | 2.5% | −2.2% | 1.6% | ||||||

| Argentina15 | Treated | 51,021 | 52.5% | 3.51 | 27.0 | 0.103 | |||||

| Controls | 44,951 | 53.7% | 3.51 | 32.0 | 0.106 | ||||||

| Difference | 6070 | ** | −1.11 | 0.00 | −5.0 | ** | −0.003 | ** | |||

| (%) diff | 13.5% | −2 | 0.0% | −15.6% | −2.5% | ||||||

| Brazil16 | Treated | 2429 | 38.3% | 2.74 | 33.3 | 0.079 | |||||

| Controls | 2487 | 54.2% | 2.77 | 39.2 | 0.089 | ||||||

| Difference | −58 | −15.9 | ** | −0.03 | ** | −5.9 | ** | −0.011 | ** | ||

| (%) diff | −2.3% | −29 | −1.2% | −15.0% | −11.9% | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oviedo-Gil, Y.M.; Cala Vitery, F.E. Teleworking and Job Quality in Latin American Countries: A Comparison from an Impact Approach in 2021. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040253

Oviedo-Gil YM, Cala Vitery FE. Teleworking and Job Quality in Latin American Countries: A Comparison from an Impact Approach in 2021. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040253

Chicago/Turabian StyleOviedo-Gil, Yanira Marcela, and Favio Ernesto Cala Vitery. 2023. "Teleworking and Job Quality in Latin American Countries: A Comparison from an Impact Approach in 2021" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040253

APA StyleOviedo-Gil, Y. M., & Cala Vitery, F. E. (2023). Teleworking and Job Quality in Latin American Countries: A Comparison from an Impact Approach in 2021. Social Sciences, 12(4), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040253