Stronger Together? Determinants of Cooperation Patterns of Migrant Organizations in Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction—Migrant Organizations and Cooperation Structures

2. Migrant Organizations and Cooperation—Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Findings

2.1. The Relationship of Migrant Organizations’ Activity Focus and Their Cooperation Patterns against the Background of Social Capital Theory

2.2. The Impact of Ressources and Structural Aspects on Collaborations

2.3. Hypotheses

3. Methods and Data

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Multivariate Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Predictors | Number of Different Cooperation Partners | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M 1 | M 2 | M 3 | M 4 | M 5 | M 6 | M 7 | M 8 | M 9 | |

| SW a: yes | 0.19 * | 0.18 * | 0.17 * | 0.16 * | 0.19 * | 0.18 * | 0.19 * | 0.18 * | 0.18 * |

| PA b: yes | 0.14 * | 0.08 | 0.13 * | 0.14 * | 0.12 | 0.14 * | 0.14 * | 0.36 * | 0.14 * |

| RCA c: yes | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.09 |

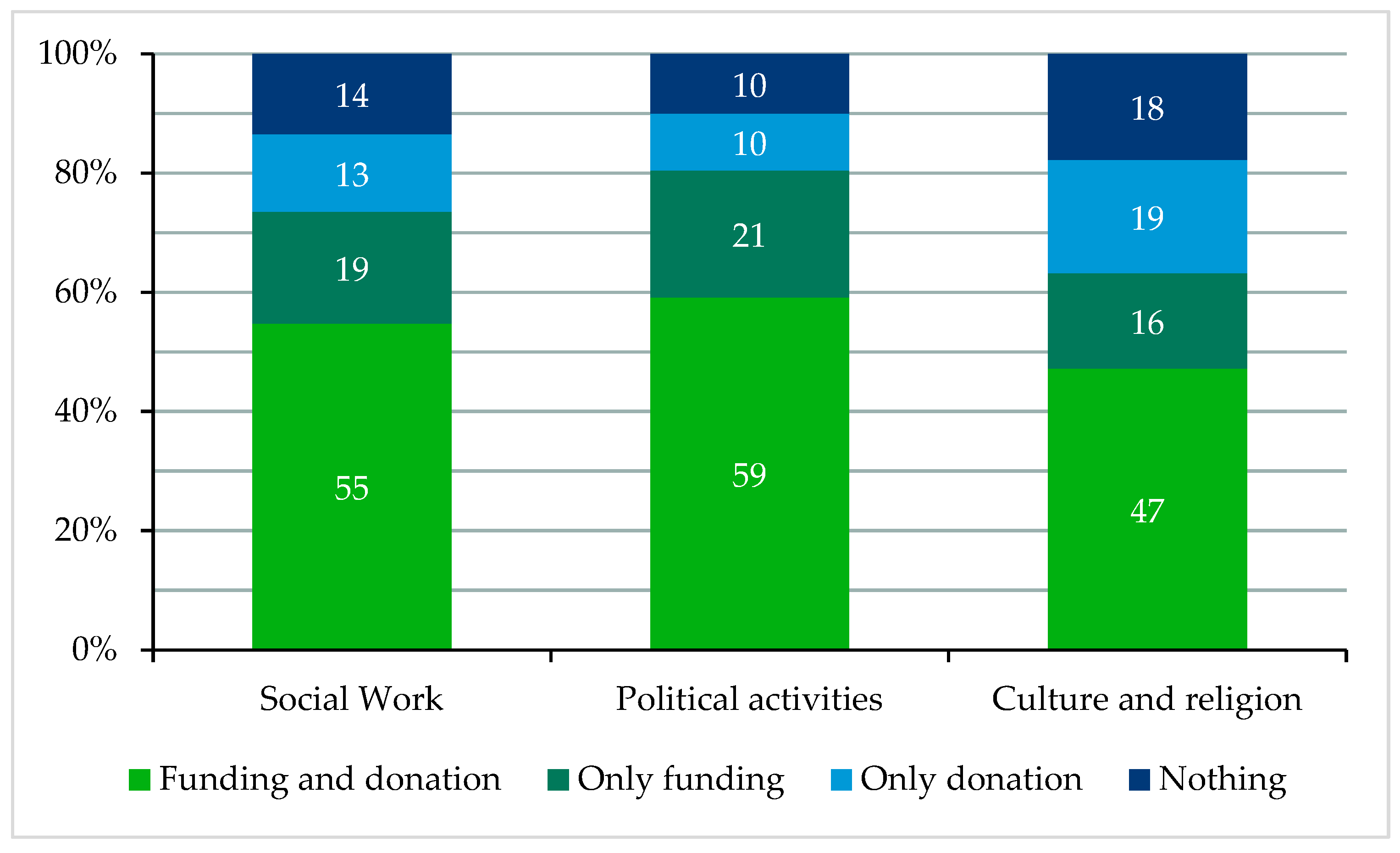

| 10 to 20 volunteers d | 0.11 * | 0.11 * | 0.10 * | 0.12 | 0.12 * | 0.11 | 0.11 * | 0.12 * | 0.11 * |

| 21 to 40 volunteers d | 0.09 * | 0.08 * | 0.08 * | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 * | 0.09 * | 0.09 * |

| 41 and more volunteers d | 0.19 * | 0.19 * | 0.17 * | 0.09 | 0.17 * | 0.25 * | 0.19 * | 0.20 * | 0.19 * |

| 1 employee e | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.25 * | 0.09 * | 0.09 * | 0.08 * | 0.09 * | 0.08 * | 0.09 * |

| 2 to 5 employees e | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 6 and more employees e | 0.19 | 0.24 * | 0.39 * | 0.24 * | 0.24 * | 0.24 * | 0.24 * | 0.25 * | 0.24 * |

| Existence of management: yes | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * |

| Funding: yes | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.11 * | 0.11 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.11 | 0.16 * | 0.07 |

| Foundation: 1992 to 2004 f | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Foundation: 2005 to 2013 f | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Foundation: After 2013 f | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| SW*1 employee | 0.00 | ||||||||

| SW*2 to 5 employees | −0.07 | ||||||||

| SW 6 and more employees | 0.05 | ||||||||

| PA*1 employee | 0.11 * | ||||||||

| PA*2 to 5 employees | 0.05 | ||||||||

| PA*6 and more employees | 0.02 | ||||||||

| RCA*1 employee | −0.21 * | ||||||||

| RCA*2 to 5 employees | −0.10 | ||||||||

| RCA*6 and more employees | −0.21 * | ||||||||

| SW*10 to 20 volunteers | −0.02 | ||||||||

| SW*21 to 40 volunteers | −0.03 | ||||||||

| SW*41 and more volunteers | 0.11 | ||||||||

| PA*10 to 20 volunteers | −0.02 | ||||||||

| PA*21 to 40 volunteers | 0.02 | ||||||||

| PA*41 and more volunteers | 0.04 | ||||||||

| RCA*10 to 20 volunteers | 0.00 | ||||||||

| RCA*21 to 40 volunteers | 0.02 | ||||||||

| RCA*41 and more volunteers | −0.08 | ||||||||

| SW*funding | −0.01 | ||||||||

| PA*funding | −0.27 * | ||||||||

| RCA*funding | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Adj R2 | 0.25 * | 0.25 * | 0.27 * | 0.25 * | 0.25 * | 0.25 * | 0.25 * | 0.26 * | 0.25 * |

| Number of cases | 606 | 606 | 606 | 606 | 606 | 606 | 606 | 606 | 606 |

| 1 | This increased need for diversity-sensitive social work goes hand in hand with a general increase in social service offers in the non-profit sector of civil society (Köcher and Haumann 2018, p. 37; Priemer et al. 2019, p. 48). |

| 2 | The landscape of migrant organizations in Germany is very diverse and developing dynamically (see also SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020a). For this reason, there is no single definition that fits all civil society, political and academic contexts equally, and on which all migrant organizations can agree with at the same time. The coexistence of different definitions also leads to terminological diversity. As a result, e.g., the terms migrant organization and migrant association are sometimes used synonymously in the scientific literature. However, in the pesent article, the term migrant association is only used with reference to umbrella associations of MOs or other alliances consisting of a majority of institutional members (predominantly migrant organizations), and which have (among other possible activites) a focus on the representation of interests towards third parties (e.g., other associations, political authorities or the public). |

| 3 | The definition closely follows that of Pries (2010, p. 16), but emphasizes somewhat more strongly that migration- or integration-related issues must be decisive for the organizations’ self-understanding. For a deeper discussion of our definition of MOs see (SVR-Forschungsbereich 2019, 2020a). |

| 4 | Although social work of MOs is in many countries of a certain importance, international studies show some differences compared to the situation in Germany. For Spain, Fauser (2016) points out that MOs historically focus in particular on political activities (p. 100). Swedish MOs, in contrast, focus primarily on cultural activities (90%), although more than a half are also engaged in political and social work (Frödin et al. 2021, p. 11). Finally, a study of MOs in Luxembourg suggests that MOs activities change depending on the needs of their target group. While MOs of a sub-Saharan background primarily offer social services, MOs of ex-Yugoslav migrants transformed from social work to cultural maintenance organizations (Gerstnerova 2016, p. 424). |

| 5 | The need for MO in the field of social work increased again after 2005, due to social and integration policy changes. On the one hand, the welfare state increasingly relied on the voluntary engagement of civil society organizations; while on the other hand, the requirements for integration policy changed with the recognition of Germany as an immigration country (Latorre and Zitzelsberger 2011, p. 54; Kellmer et al. 2022, p. 401f). |

| 6 | This term refers to the diverse field of non-profit organizations which serve the general interest and which are neither connected to nor managed by state authorities. |

| 7 | The authors distinguish between cooperation with an umbrella association, coaching/mentoring, tandem-projects, project conception, publicity actions and access to a certain target group (Hunger and Metzger 2011, p. 11). |

| 8 | That MOs can fulfill different functions for their members has already been described by Breton (1964), who pointed out that an institutionalized innerethnic infrastructure (provided by MOs) might, on the one hand, substitute institutions of the host country and enhance the relevance of migrants’ national identity to a certain degree. On the other hand, this infrastructue can also bring important issues and challenges of people with a migration background to the public (p. 198f). |

| 9 | Following Elwert’s hypotheses of integration within the ethnic group a controversial discussion between different researchers came up, if migrant organizations enhance or reduce integration processes (the so-called Esser–Elwert controversy). As this article does not focus on MOs’ effects on integration and furthermore rejects the ‘either or’ perspective in this context, we will not repeat the arguments of this discussion. However, the debate of the effects of bonding and bridging social capital in a dichotomous perspective suggests that the Esser–Elwert controversy continues under a new label (Klie 2022, p. 130). |

| 10 | Next to the fact that most studies show a wide network of cooperation partners of MOs, over 90% of MOs also open their offers to non-members (SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020a, p. 19), which supports the assumption that bridging social capital is an important aspect of MOs’ work. |

| 11 | In this article, we use the bonding/bridging concept only on the organizational level, not on the individual level of MOs’ members or clients. |

| 12 | In an explorative Study, Huth interviewed 85 MOs in Hesse at the end of 2011 (Huth 2011, p. 9). Due to the small number of cases, the results give more impressions, but cannot deliver statically reliable results. |

| 13 | In Belgium, for instance, the state forces to join umbrella associations to gain access to public funding (Hooghe 2005, p. 980). |

| 14 | Although resource mobilization theory bear primarily on financial support, there is empirical evidence for a strong correlation between financial support (e.g., funding) and the development of a staff (Fauser 2016, p. 94; SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020a, p. 75ff). |

| 15 | This hypothesis has already been tested based on the individual activities and three MO types developed by a cluster analysis. In this article, we re-categorized the activities into broader activity areas (see section Methods and Data), which makes it necessary to look again at this relationship. |

| 16 | To increase response rates, the invitation via e-mail was combined with contacting by telephone, if both e-mail address and telephone number were available. If there was only a telephone number, interviewers asked after the e-mail address within the call to send an invitation. We chose this procedure also to get a less selective sample. |

| 17 | Next to the personal invitations of MOs in our data bank, some MO associations also sent the link to their members via e-mail to invite MOs that are not located in the four federal states to participate as well. |

| 18 | 4.122 in North Rhine-Westphalia, 1.766 in Bavaria. 732 in Berlin and 231 in Saxony. |

| 19 | For details regarding methods and research process see the methodological report (SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020b). |

| 20 | Offered answers were: “state policy/administration (e.g., state ministries)”; “federal policy/administration (e.g., federal ministries)”; “municipal administrations”, “district administrations”; “other migrant organizations”; “welfare associations”; “churches and religious communities”; “other non-profit associations/organisations”; “commercial enterprises”; “foundations”; “universities and colleges”; “informal associations and initiatives”; “twin cities abroad”; “authorities/organisations abroad”; “others”. |

| 21 | A minor importance in this context only refers to the quantitative share of MOs’ collaborations. That does not mean that these cooperation partners cannot be of particular importance for individual MOs. |

| 22 | We restricted the number of activity fields the MOs could choose, because most MOs are multifunctional organizations, as shown above. To find out the differences between the MOs in their portfolio, we decided to survey only the five most important activities. The results confirm this decision. On average, the MOs in the survey mentioned 4.4 activity areas (SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020a, p. 26). |

| 23 | The activity fields were: “offers for women”; “anti-discrimination work”; “employment agency”; “exchange between people with and without migrant backgrounds”; “consulting”; “education”; “parental/family work”; “development cooperation”; “health”; “child and youth work”; “artistic-cultural activities (e.g., music, theatre)”; “cultivation of culture(s) of origin”; “cultivation/teaching of language of origin”; “political representation of interests”; “religion”; “senior citizens’ work”; “sport”; “translations”; “environmental protection and nature conservation”; “support for refugees”; “representation of professional interests”; “science and research”; and “other”. |

| 24 | In the main publication of this research project, we differentiated three MO-types via cluster analysis based on the self-designation of the surveyed MOs. Although these types had different foci in their work, it was established that many MOs were active in a lot of areas (SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020a, p. 39). This is also reflected in other studies. Studies of religious migrant communities, for instance, show that many of these organizations also do social work for their members (Halm et al. 2012; Halm and Sauer 2015; Klöckner 2016, p. 269; Nagel 2016, p. 92). |

| 25 | The number of employees includes all kinds of paid work in the organization, e.g., permanent employees as well as freelancers, so-called Minijobs or paid internships. |

| 26 | MOs were asked if they received funding, donation, funding and donation, or none of them in 2019. We did not ask about the amount of funding or donation, to avoid risking an interview abort when faced with these sensitive questions, which is particularly likely in an online survey. |

| 27 | To make sure that there is no strong multi-collinearity between the independent variables, which might influence the prediction, we checked the variance inflation factors (VIF) of predictor variables for all regression models. For the interpretation, we follow the conservative recommendation of Urban and Mayerl (2006, p. 232) and regard a VIF > 5 as an indication of collinearity problems. All VIF were below 2, so there was no sign for multi-collinearity. |

| 28 | We also calculated models considering the income as a second predictor for financial resources. As this variable has many missing cases and we hardly could find effects, we excluded it from our analysis. |

| 29 | As mentioned above, we did the same for the year of foundation. In our sample are few MOs that were founded in the 1950s and 1960s, which would have a strong influence on the average year of foundation. |

| 30 | Cramer’s V is −0.14* for the correlation between cultural/religious activities and social work, and −0.24* for the correlation between cultural/religious and political activities. |

| 31 | Since the three activity fields represent three independent variables, testing for significance between the three fields is not directly possible. |

| 32 | However, the explanatory power of this finding is limited, as our survey only asked about the number of unpaid volunteers, and not about how regularly and consistently they volunteer. This question is likely to be significant, as the three fields of action sometimes require different levels of commitment: In many areas of social work—and, to some extent, also in the cultural-religious sphere—voluntary commitment requires a certain constancy. In other words: it may be easier in the political sphere to get involved only once in a while. In the case of political activity, perhaps people were also counted who “only” designed or distributed a flyer once, while respondents of MOs with a clear focus on social work or culture/religion were more likely to have thought of regularly engaged people when answering the question. Even though this interpretation is speculative, it emphasizes a certain need for a more detailed revision of different ideas and profiles of unpaid volunteers in MOs in further research. |

| 33 | This result can partly be explained with funding guidelines, because they often exclude religious projects and those of cultural maintenance (SVR-Forschungsbereich 2020a, p. 68). |

| 34 | We use odds ratios to interpret the correlations. However, since this coefficient is not linearly related to the probabilities, we primarily interpret the direction of the correlation, instead of the effect size (Behnke 2015, p. 75). |

| 35 | As the variable to measure the diversity of cooperation partners has been calculated on the basis of the different cooperation partners, this result does not deliver additional knowledge. Indeed, we see almost the same effects as in Table 2. |

| 36 | We also calculated this interaction for the activity culture and religion. Paid employees appear to be less important in this area than for other activities. When paid employees and religious/cultural activities co-occur, there is a lower cooperation diversity than is the case for other activity foci. |

References

- Amelina, Anna, and Thomas Faist. 2008. Turkish Migrant Associations in Germany: Between Integration Pressure and Transnational Linkages. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 24: 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barglowski, Karolina, and Lisa Bonfert. 2022. The Affective Dimension of Social Protection: A Case Study of Migrant-Led Organizations and Associations in Germany. Social Sciences 11: 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, Joachim. 2015. Logistische Regressionsanalyse. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, Raymond. 1964. Institutional Completeness of Ethnic Communities and the Personal Relations of Immigrants. American Journal of Sociology 70: 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, Rauf, and Michael Kiefer. 2016. Muslimische Wohlfahrtspflege in Deutschland. Eine historische und systematische Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Danese, Gaia. 2001. Participation beyond Citizenship: Migrants‘ Associations in Italy and Spain. Patterns of Prejudice 35: S69–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwert, Georg. 1982. Probleme der Ausländerintegration. Gesellschaftliche Integration durch Binnenintegration? Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 34: 717–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fauser, Margit. 2016. Migrants and Cities. The Accommodation of Migrant Organizations in Europe. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag, Markus, and Richard Traunmüller. 2008. Sozialkapitalwelten in Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 2: 221–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frödin, Olle, Axel Fredholm, and Johan Sandberg. 2021. Integration, cultural preservation and transnationalism through state supported immigrant organizations: A study of Sweden’s national ethnic associations. Comparative Migration Studies 9: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstnerova, Andrea. 2016. Migrant associations’ dynamics in Luxembourg. Ethnicities 16: 418–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góis, Pedro, and José Marques. 2023. Migrant associations, other social networks of Portuguese Diaspora, and the modern political engagement of non-resident citizens. European Political Science 22: 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günzel, Eva, Matthias Benz, and Sören Petermann. 2022. Migrant Organizations and Their Networks in the Co-Production of Social Protection. In Migrant Organizations: Multifunctional and Flexible Providers of Social Protection and Welfare in Changing Societies. Edited by Karolina Barglowski, Sören Petermann and Thorsten Schlee. Special Issue. Social Sciences 11: 585. [Google Scholar]

- Halm, Dirk. 2013. (Des-)integrative Wirkungen von Migrantenverbänden bzw. Migrantenorganisationen. Stand der wissenschaftlichen Diskussion und aktuelle Entwicklungen. Essen and Berlin: Expertise im Auftrag des SVR. [Google Scholar]

- Halm, Dirk, and Martina Sauer. 2015. Soziale Dienstleistungen der in der Deutschen Islam Konferenz vertretenen religiösen Dachverbände und ihrer Gemeinden. Eine Studie im Auftrag der Deutschen Islamkonferenz. Berlin: Deutsche Islamkonferenz. [Google Scholar]

- Halm, Dirk, and Martina Sauer. 2018. Qualifizierungsbedarfe muslimischer Gemeinden im Bereich sozialer Dienstleistungen. Soziale Passagen 10: 321–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, Dirk, and Martina Sauer. 2023. Cross-Border Structures and Orientations of Migrant Organizations in Germany. Journal of International Migration and Integration 24: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, Dirk, Martina Sauer, Jana Schmidt, and Anja Stichs. 2012. Islamisches Gemeindeleben in Deutschland. Im Auftrag der Deutschen Islam Konferenz. Forschungsbericht 13 des BAMF. Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. [Google Scholar]

- Halm, Dirk, Martina Sauer, Saboura Naqshband, and Magdalena Nowicka. 2020. Wohlfahrtspflegerische Leistungen von säkularen Migrantenorganisationen in Deutschland, unter Berücksichtigung der Leistungen für Geflüchtete. Baden-Baden: Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Halman, Loek, and Thorleif Pettersson. 2003. Religion and Social Capital Revisted. In Religion in Secularizing Society. The European’s Religion at the End of the 20th Century. Edited by Loek Halman and Ole Ris. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 162–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, Jeremy. 1997. Ethnic Organizations and the Welfare State: The Impact of Social Welfare Programs on the Formation of Indochinese Refugee Associations. Sociological Forum 12: 279–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, Marc. 2005. Ethnic Organisations and Social Movement Theory: The Political Opportunity Structure for Ethnic Mobilisation in Flanders. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31: 975–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, Uwe. 2004. Wie können Migrantenselbstorganisationen den Integrationsprozess betreuen? Wissenschaftliches Gutachten im Auftrag des Sachverständigenrats für Zuwanderung und Integration und des Bundesministeriums des Innern der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Münster and Osnabrück: Universität Osnabrück. [Google Scholar]

- Hunger, Uwe, and Stefan Metzger. 2011. Kooperation mit Migrantenorganisationen—Studie im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Münster: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, Susanne. 2011. Migrantenorganisationen in Hessen—Motivation und Hinderungsgründe für bürgerschaftliches Engagement: Explorative Studie im Rahmen des Hessischen Landesprogramms Modellregionen Integration im Auftrag des Hessischen Ministeriums der Justiz, für Integration. Frankfurt am Main: Hessisches Ministerium der Justiz, für Integration und Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, Susanne. 2019. Die Rolle von Migrantenorganisationen im Flüchtlingsbereich. Bestandsaufnahme und Handlungsempfehlungen: Studie mit Förderung der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Integration. Frankfurt am Main: INBAS-Sozialforschung GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Kellmer, Ariana, Ute Klammer, and Thorsten Schlee. 2022. Wohlfahrtsverbände und Migrantenorganisationen im transformierten Sozialstaat—zwischen universalistischen sozialen Dienstleistungen und adressatengebundener Integrationspolitik. In Gesellschaft und Politik verstehen. Frank Nullmeier zum 65. Geburtstag. Edited by Martin Nonhoff, Sebatian Haunss, Tanja Klenk and Tanja Pritzlaff-Scheele. Frankfurt am Main and New York: Campus, pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Klie, Anna Wiebke. 2022. Zivilgesellschaftliche Performanz von religiösen und säkularen Migrantenselbstorganisationen. Eine Studie in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, Jennifer. 2016. Freiwillige Arbeit in gemeinnützigen Vereinen. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Köcher, Renate, and Wilhelm Haumann. 2018. Engagement in Zahlen. In Engagement und Zivilgesellschaft. Edited by Thomas Klie and Anna Wiebke Klie. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 15–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2007. Sozialkapital: Eine Einführung. In Sozialkapital. Grundlagen und Anwendungen. Edited by Axel Franzen and Markus Freitag. Sonderheft 47, Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbruck, Christel. 2001. Was ist Kooperation? Kooperation im Lichte der Tätigkeitstheorie. Arbeit. Zeitschrift für Arbeitsforschung, Arbeitsgestaltung und Arbeitspolitik 10: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, Volker, Bettina Westle, and Sigrid Roßteutscher. 2008. Dimensionen und Messung sozialen Kapitals. In Sozialkapital. Eine Einführung. Edited by Bettina Westle and Oscar W. Gabriel. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, Patricia, and Olga Zitzelsberger. 2011. MigrantInnenselbstorganisationen und Soziale Arbeit. Was der Zusammenarbeit auf Augenhöhe im Wege steht. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 24: 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Paul S., and Stanley Lemeshow. 2008. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Mualem Sultan, Marie. 2022. Auf Partnersuche? Staat und Migrantendachverbände in der Integrationspolitik. SVR-Policy Brief 2022-4. Berlin: Sachverständigenrat für Integration und Migration (SVR) gGmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Alexander-Kenneth. 2016. Religiöse Migrantenorganisationen als soziale Dienstleister. Eine potentialorientierte Perspektive. Soziale Passagen 8: 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, Siglinde. 2011. Migrantenselbstorganisationen—Träger des Engagements von Migrantinnen und Migranten. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 24: 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odmalm, Pontus. 2004. Civil society, migrant organisations and political parties: Theoretical linkages and applications to the Swedish context. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30: 471–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predelli, Line Nyhagen. 2008. Political and Cultural Ethnic Mobilisation: The Role of Immigrant Associations in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34: 935–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priemer, Jana, and Mara Schmidt. 2018. Engagiert und doch unsichtbar? Migrantenorganisationen in Deutschland. Policy Paper 02 des Stifterverbands für die Deutsche Wissenschaft. Essen: Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft e.V. [Google Scholar]

- Priemer, Jana, and Mara Schmidt. 2019. Neue deutsche Zivilgesellschaft. Eine Bestandsaufnahme des Engagements von Migrantenorganisationen in Deutschland, Unpublished Manuscript.

- Priemer, Jana, Antje Bischoff, Christian Hohendanner, Ralf Krebstakies, Boris Rump, and Wolfgang Schmitt. 2019. Organisierte Zivilgesellschaft. In Datenreport Zivilgesellschaft. Edited by Holger Krimmer. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 7–54. [Google Scholar]

- Priemer, Jana, Holger Krimmer, and Anaël Labigne. 2017. Vielfalt verstehen. Zusammenhalt stärken. ZiviZ-Survey 2017. Berlin: Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft e.V. [Google Scholar]

- Pries, Ludger. 2010. (Grenzüberschreitende) Migrantenorganisationen als Gegenstand der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung: Klassische Problemstellungen und neuere Forschungsbefunde. In Jenseits von “Identität oder Integration”: Grenzen überspannende Migrantenorganisationen. Edited by Ludger Pries and Zeynep Sezgin. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 15–60. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 1995. Tuning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America. PS: Political Science and Politics 28: 664–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2020. Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Revised and Updated ed. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, Meike, Kristina Stegner, Olga Zitzelsberger, Patricia Latorre, and Iva Kocaman. 2010. Forschungsstudie Migrantinnenorganisationen in Deutschland. Studie im Auftrag des BMFSFJ. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. [Google Scholar]

- Sardinha, João. 2010. Immigrantenverbände und Möglichkeiten der Teilhabe in Portugal: Intervention zu welchem Preis? In Jenseits von “Identität oder Integration”. Grenzen überspannende Migrantenorganisationen. Edited by Ludger Pries and Zeynep Sezgin. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 233–64. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2022. Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2021. Fachserie 1 Reihe 2.2, 2021 (Erstergebnisse). Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. [Google Scholar]

- SVR-Forschungsbereich. 2019. Anerkannte Partner—unbekannte Größe? Migrantenorganisationen in der deutschen Einwanderungsgesellschaft. Policy Brief des SVR-Forschungsbereichs 2019-3. Berlin: Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR) GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- SVR-Forschungsbereich. 2020a. Vielfältig Engagiert—Breit Vernetzt—Partiell Eingebunden? Migrantenorganisationen als gestaltende Kraft in der Gesellschaft. Studie des SVR-Forschungsbereichs 2020-2. Berlin: Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR) GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- SVR-Forschungsbereich. 2020b. Vielfältig Engagiert—Breit Vernetzt—Partiell Eingebunden? Migrantenorganisationen als gestaltende Kraft in der Gesellschaft. Methodenbericht. Berlin: Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR) GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, Dieter, and Jochen Mayerl. 2006. Regressionsanalyse: Theorie, Technik und Anwendung, 2nd ed. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, Floris. 2013. Mutualism, Resource Competition and Opposing Movements among Turkish Organizations in Amsterdam and Berlin, 1965–2000. The British Journal of Sociology 64: 453–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, Floris, and Elif Keskiner. 2017. Bonding or Bridging? Professional Network Organizations of Second-Generation Turks in the Netherlands and France. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 301–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, Floris, and Martijn Brünger. 2014. The Organisational Legitimacy of Immigrant Groups: Turks and Moroccans in Amsterdam. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40: 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Karin. 2013. Migrantenorganisationen und Staat. Anerkennung, Zusammenarbeit, Förderung. In Migrantenorganisationen. Engagement, Transnationalität und Integration. Tagungsdokumentation im Auftrag der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Edited by Günther Schultze and Dietrich Thränhardt. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

| Fields of Activities | % | Number of Volunteers (Mean) | Number of Employees (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social work | 77 | 42.0 | 6.7 |

| Political activities | 29 | 56.8 | 7.4 |

| Culture and religion | 59 | 42.9 | 3.6 |

| Predictors | Membership in Association | Cooperation with… | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Institutions | Civil Society | Religious Communities | ||

| Social work: yes | 1.40 | 1.78 ** | 3.33 *** | 1.33 |

| Political activities: yes | 1.79 * | 2.01 ** | 1.55 | 0.82 |

| Cultural and religion: yes | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 1.02 |

| 10 to 20 volunteers a | 0.93 | 1.38 | 1.24 | 1.95 ** |

| 21 to 40 volunteers a | 1.23 | 1.28 | 1.74 | 1.70 |

| 41 and more volunteers a | 1.45 | 1.15 | 2.45 * | 3.51 *** |

| 1 employee b | 1.41 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 2.19 * |

| 2 to 5 employees b | 2.13 ** | 0.61 | 1.42 | 1.04 |

| 6 and more employees b | 1.99 * | 2.60 ** | 1.36 | 1.07 |

| Existence of management: yes | 1.32 | 1.26 | 1.28 | 1.09 |

| Funding: yes | 1.48 | 2.05 ** | 1.89 * | 0.41 *** |

| Year of Foundation: 1992 to 2004 c | 0.58 * | 1.25 | 1.51 | 0.82 |

| Year of Foundation: 2005 to 2013 c | 0.49 * | 0.57 * | 1.80 | 0.66 |

| Year of Foundation: after 2013 c | 0.28 *** | 0.60 | 1.81 | 0.73 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.11 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.08 *** |

| Number of cases | 591 | 606 | 606 | 606 |

| Predictors | Number of Different Cooperation Partners |

|---|---|

| Social work: yes | 0.18 *** |

| Political activities: yes | 0.14 *** |

| Religious and cultural activities: yes | −0.06 |

| 10 to 20 volunteers a | 0.11 ** |

| 21 to 40 voluntieers a | 0.09 * |

| 41 and more voluntieers a | 0.19 *** |

| 1 employee b | 0.09 * |

| 2 to 5 employees b | 0.02 |

| 6 and more employees b | 0.24 *** |

| Existence of management: yes | 0.10 * |

| Funding: yes | 0.10 ** |

| Year of Foundation: 1992 to 2004 c | 0.07 |

| Year of Foundation: 2005 to 2013 c | 0.01 |

| Year of Foundation: After 2013 c | 0.01 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.25 *** |

| Number of cases | 606 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Friedrichs, N.; Mualem, M. Stronger Together? Determinants of Cooperation Patterns of Migrant Organizations in Germany. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040223

Friedrichs N, Mualem M. Stronger Together? Determinants of Cooperation Patterns of Migrant Organizations in Germany. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040223

Chicago/Turabian StyleFriedrichs, Nils, and Marie Mualem. 2023. "Stronger Together? Determinants of Cooperation Patterns of Migrant Organizations in Germany" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040223

APA StyleFriedrichs, N., & Mualem, M. (2023). Stronger Together? Determinants of Cooperation Patterns of Migrant Organizations in Germany. Social Sciences, 12(4), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040223