1. Introduction

Somerville, Massachusetts, a densely populated city tucked north of Boston, has long been a port of entry for new immigrants arriving in the United States. Beginning in the early part of the twentieth century, Irish and Italian immigrants began settling in Somerville, attracted by its growing industrial economy and affordable triple-decker Victorian homes that still line the city’s streets. By the 1980s, immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador, and Brazil settled in Somerville, shifting the city’s demographics, and requiring new accommodations from the city and its schools to help the diverse immigrant community thrive (

Ostrander 2013). In 1987, the city proclaimed itself a sanctuary city, a declaration re-issued in 2014 and again in the wake of Donald Trump’s election in 2016. During the Trump presidency and the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic that followed, the number of young migrants that showed up at the doors of Somerville schools slowed to a trickle. However, in the 2021–2022 school year, over 350 children—almost an entire school’s worth—arrived in the city’s school district of fewer than 5000 students, many coming directly from the Texas–Mexico border, more than a thousand miles south of the city. Most were from Brazil, although a sizable number also came from Central America. While the majority migrated with their families, a not insignificant number had made the arduous journey north on their own.

As these children made their way to a city they had never seen, profoundly restrictive national policies framed their migration and settlement. The so-called “Remain in Mexico” policy, officially named the Migration Protection Protocol (MPP), was an effort implemented in 2018 by the Trump administration to require migrants to wait in Mexico while they sought asylum in the United States. Title 42, an emergency measure put in place during the pandemic that was less about public health and more about excluding poor migrants of color, has, as of this writing, yet to be rescinded by the Biden administration. Aside from these recent policies, U.S. immigration law has a long history of nativism and exclusion. For immigrants who do not have access to forms of lawful status, unauthorized migration, sometimes without inspection at the border, is the only option. Once in the United States unlawfully, it is extremely arduous to regularize one’s status, leaving millions of immigrants, and the families in which they are embedded, trapped in a system where they cannot access many basic rights and resources.

Scholars of migration rightfully center our collective attention on the exclusionary policies and discourses that define immigrants’ experiences in their communities of reception. This research has long documented how features of immigrants’ context of reception, such as availability of economic opportunity, degree of racial residential segregation, and presence of co-ethnic communities, facilitate incorporation or keep immigrants at the margins of social, political, cultural and economic life (

Portes and Rumbaut 2014). Racial, economic, and gendered inequalities shape access to formal citizenship, the utmost category of legal belonging, even if access to citizenship alone rarely generates equality in rights, power, and recognition (

Shachar 2021). For immigrants who are racialized as not white, racial exclusion is intertwined with immigration policies that function to create precarity and demarcate the boundaries between who belongs and who does not (

Marquez et al. 2021;

Menjívar 2021).

Yet the children who showed up in Somerville in 2021, like those arriving in geographically diverse communities across the United States also found recognition, care, and support as they began their lives as U.S. residents. From encountering another child who migrated from the same country to building a relationship with a thoughtful teacher to participating in a church youth group in Spanish or Portuguese, these young people develop pathways to belonging, even as their opportunities are circumscribed by broader anti-immigrant laws, policies, and discourses. Despite daunting structural and cultural barriers, these young immigrants, whether lawfully present or not or somewhere in-between, continue to live out their lives, becoming incorporated, albeit to different degrees and through different pathways, into their new landscapes (

Bloemraad 2006;

Suárez-Orozco et al. 2008). As Anna

Korteweg (

2017) argues, migrants ‘always-already belong,’ are always-already woven into the places they reside, regardless of whether they are symbolically, legally or socially included.

It is the tension between the power of anti-immigrant laws, policies, and discourses and the practices of young people’s ‘always-already belonging’ that lead us to theorize a model of

spaces of belonging for immigrant youth. The contradictions between the intimacy of belonging and the harsh laws and policies that circumscribe immigrants’ lives evolve over the life course. Children and young people may or may not have been part of the decision to migrate, yet they often have access to institutions where they can learn a new language quickly and develop relationships with more ease than adults. When children migrate at a particularly young age, they are soon indistinguishable in many aspects from co-ethnic, non-migrant peers. Yet as they grow, their formal belonging is intertwined with their access to legal, secure immigration statuses (

Gonzales 2011). In this theoretical paper, then, we intentionally focus on migrant youth, with particular attention to those young people who are made vulnerable through the denial of lawful immigration status.

We argue that spaces of belonging, where connection, sustenance, and recognition are readily available, are as central to immigrant youths’ experiences of settlement as the exclusionary laws and policies that constrain their opportunities, well-being, and integration. We contend that place matters deeply in the lives of immigrant young people and their efforts to belong. The demographic, political, legal, and physical geographies of the towns, cities, and rural areas where young people live fundamentally shape how migrant youth and their families construct and access spaces of belonging. These local geographies of belonging mediate federal laws and discourses, functioning as a filter for young people’s access to belonging through the relationships and communities they encounter.

By developing a model of spaces of belonging that encompasses immigrant young people’s experiences at the relational, community, and national level, we make several theoretical interventions that we hope will be useful to scholars across disciplinary boundaries seeking to document the barriers and opportunities young immigrants face as they build new worlds in the United States. First, we move beyond dichotomous understandings of marginalization or assimilation by emphasizing the fluidity and agency that are fundamental to migrant youth as they strive towards belonging. Being included does not have to mean erasing ethnic, linguistic, and national identities, nor is it contingent on acceptance by others with more racial, economic, and political power. Through this reconceptualization of assimilation, we offer a second contribution: for migrant youth and their families, illegality and belonging can and do co-exist. By demonstrating how relationships, community practices and institutions, and national laws and discourses can generate both belonging and exclusion, we shine new light on how youth negotiate their precarious inclusion, especially for those who are racialized as outsiders. Finally, scholars often seek to make sense of immigrant youth’s lives through the quantifiable consequences of immigration laws and policies. Belonging is not easily operationalized, and it rarely captures public attention in the same way that a crisp statistical portrait might. However, it is, ultimately, a fundamental human experience and an essential human right, especially in an era where the rights of non-citizens are tenuous at best.

In this article, we offer new ways of understanding how place informs migrant youth and children’s sense of inclusion and agency, illuminating how spaces of belonging at the relational, community, and national level support their dignity and well-being. In doing so, we expand our collective attention beyond exclusionary laws, policies, and practices to provide more nuanced examinations of how immigrant children claim a sense of dignity, hold on to their well-being, and create meaningful communities. These practices of belonging are not merely passive responses to spaces created by others or to pressures of assimilation. They are practices of agency and power, of claiming the right to be seen and included in a world which too often constrains immigrant youth’s efforts to author their own lives.

2. Theorizing Place, Migration, and Belonging

2.1. Exclusion in Migrant Lives

Theorizing belonging requires mapping the conditions which prohibit full inclusion for young immigrants and their families. While we focus specifically on young people throughout the paper, young migrants are embedded in families that are forced to confront the weight of exclusion wrought by U.S. immigration policies. Therefore, in this section, we broaden our scope to consider how exclusion operates in the lives of both adult and youth immigrants.

Illegality, understood as a ‘distinctly spatialized and typically racialized social condition for undocumented migrants [which] provides an apparatus for sustaining their vulnerability and tractability,’ is a means of marking migrants as other, regardless of their actual immigration status (

DeGenova 2002, p. 439). It becomes a mechanism for racializing and excluding migrants from the ‘imagined community’ of a nation-state and generates ‘spaces of non-existence’ where a person’s inability to access lawful status creates a symbolic nether region where one is absent from one’s country of origin but not officially recognized elsewhere (

Anderson 2006;

Coutin 2003). Upheld in part through the constant threat of deportation, illegality and its cousin, liminal legality, which situates immigrants as only partially belonging through time-limited immigration statuses that are revocable and impermanent, are defined by pervasive uncertainty and vulnerability in nearly every domain of life (e.g.,

Asad and Rosen 2019;

Bruhn 2022;

Enriquez 2020;

Farfán-Santos 2019;

Gonzales 2015;

Menjívar 2006). Relatedly, the concept of legal violence illuminates how immigration policies and enforcement practices inflict systemic harm on immigrants (

Menjívar and Abrego 2012; see also

Gonzales and Chavez 2012). Legal violence is generated through a confluence of factors, including U.S. intervention in Central American countries in the 1970s and 1980s, resulting in instability and violence that forced people to flee, the criminalization of immigration rules which had previously been considered civil offenses, and the militarization of the U.S.–Mexico border (

Menjívar and Abrego 2012). It tears families apart, makes immigrant employees vulnerable to abuse, and undermines families’ efforts to make a better life for themselves and their children (

Abrego 2014;

Castañeda 2019;

Enriquez 2020;

López 2021). In short, legal violence causes immediate damage and systematically blocks future opportunities for belonging and integration.

The devastating impacts of illegality and legal violence are buttressed by anti-immigrant, racialized discourses and national rhetorics that perpetuate the social exclusion of migrants. In the United States immigrants who are not white, not European, and not Christian, are often viewed as less worthy of full membership and are often assumed to have migrated without authorization (

Chavez 2008;

García 2018). This ‘social illegality’ is woven into white non-Hispanic Americans’ perceptions of immigrants and anyone who may be racially or socially associated with immigrants, constraining access to opportunities and resources, for adults and young people alike (

Flores and Schachter 2018;

Flores-González 2018). This social exclusion of immigrants targets undocumented immigrants, their authorized counterparts, and citizen family members, although to different extents and pathways.

Legal and “illegal,” then, are less permanent states of being and more a spectrum that shifts according to changes in policy, life course, and individual decisions (

Kubal 2013). For young immigrants, even as discourses of deservingness situate (some of) them as more worthy of formal inclusion and even as their families strive to protect them from racist, xenophobic discourses and policies, these exclusions nevertheless shape their trajectories. The relational, community, and even national spaces of belonging that we conceptualize in this paper do not override these forces entirely. However, we argue that spaces of belonging co-exist with these exclusionary forces, providing sustenance, dignity, and the opportunity to develop individual and collective power in the face of struggles against racialized illegality. By acknowledging how illegality operates to produce marginalization, we can better understand how spaces of belonging engender meaningful opportunities for connection, agency, and worthiness for immigrant children and youth.

2.2. Operationalizing Place

The ramifications of illegality, deportability, and legal violence are not limited to a particular geographic location. Locally bounded places are embedded within more expansive conceptions of place, including counties, states, and regions. Often, the boundaries between these layers of place are clearly demarcated; other times they are blurry or less relevant to those who move between them.

Golash-Boza and Valdez (

2018) refer to these as ‘nested contexts of reception’ and point to the necessity of investigating how people build community and obtain resources within a federal environment that is distinctly unsupportive of immigrants. Contemporary enforcement practices, coupled with policies that vary by state and municipality, make these different levels of place important in the lives of immigrants and their families (

Simmons et al. 2020;

Spencer and Delvino 2019). The contrasts and contradictions between the layers of contexts produce uneven legal geographies that immigrants and their communities navigate as they carry out the daily routines of their lives (

Burciaga et al. 2019;

Valdivia 2019). Place, in this sense, is not an abstract concept. It is the concrete features of the natural and built environment that people move through and interact with on a daily basis (

Tuan 1977).

Belonging and exclusion play out in place-specific ways, in response to the physical features of the landscape and the uneven legal geographies of immigration policies (

Burciaga et al. 2019;

Coleman 2007;

García and Schmalzbauer 2017). Place can be generative, allowing immigrants to create spaces of belonging from the often taken-for-granted features of their environments, from the corner store selling ethnic foods to the church sidewalk where immigrant families gather after worship. This is not to say that integration is necessary for spaces of belonging to be valuable; Latina immigrant mothers, for example, find solidarity within the parameters of district programs precisely because the programs are dominated by other immigrants who share similar linguistic, racial, and ethnic identities (

Bruhn 2023). In these and other locales, immigrants claim their right to participate visibly and assert the common aspects of their collective identities, including but not limited to race, language, religious identity, ethnicity, and cultural preferences. At the same time, place can limit or make invisible the construction of spaces of belonging by those categorized as ethno-racial outsiders (

Damery 2019;

Finney et al. 2019). In towns and cities where support for restrictionist politicians is high and made visible by signs or flags amplifying xenophobic attitudes, immigrants may be less inclined to form easily recognizable spaces of ethnic or linguistic solidarity. In fact, they may physically strive to assimilate to avoid being marked as deportable (

García 2019). The threat of deportation, or deportability more generally, also varies by local geographies, contributing to immigrants’ fears of deportation and struggles to develop secure social connections (

Simmons et al. 2020). Rarely do exclusionary places entirely eradicate spaces of belonging, however. Even in places defined by nativism and restrictive subnational policies, spaces of belonging sustain young immigrants’ well-being and academic aspirations (

Flores 2021;

Maghbouleh 2017).

Drawing on this robust scholarship, we define place as consisting of four interrelated geographic features of the communities where young migrants settle: (1) the racial and socio-economic composition of students’ neighborhoods and schools; (2) local political dynamics; (3) laws and policies affecting families and (4) natural and built physical environments. Much of the scholarship at the intersection of place and migration emphasizes how these geographical features shape adult immigrants’ lives. In contrast, we shine a light on how place is intertwined with young immigrants’ access to and construction of spaces of belonging at the relational, community, and national level.

For all young people, immigrants or not, the schools and communities they encounter as they grow are marked by extraordinarily high levels of segregation, socio-economic class, and race. Understanding migrant youth’s experiences of belonging requires careful attention to these demographics of their daily lives. Similarly, the political environment of the broader communities in which immigrant young people are embedded has profound implications for inclusion, both interpersonally and institutionally. Although politicians on both sides of the aisle have long supported restrictive immigration policies, in a moment of stark socio-political divides, issues surrounding immigration have become even more central to how Americans draw boundaries among themselves (

Denvir 2020;

Elcioglu 2019). Both the symbolic and substantive domains of politics are relevant to how place affects access to and participation in spaces of belonging. A sign for an explicitly xenophobic candidate, for instance, may be a symbolic mechanism through which young people feel marked as outsiders. Subnational immigration laws, whether restrictive or inclusionary, are an example of how politics substantively shapes the relationship between place and belonging.

Beyond broad strokes of inclusionary or exclusionary laws, our analysis of place, and its impact on children’s belonging, calls attention to the specific policies that affect the quotidian routines of immigrant families. Driver’s licenses, for instance, are available to undocumented immigrants in sixteen states as of 2022. While only older adolescents can drive, these laws vicariously shape younger immigrants’ lives. If family members cannot legally drive, families are forced to make decisions about access to work, school, and activities that either put them at risk for family separation through deportation or drastically restrict children’s opportunities. Of course, the natural and built environments mediate the power of driver’s license laws. In cities with reliable public transportation–and enough affordable housing to make access to public transportation possible–A driver’s license might be less consequential than in rural areas. Yet for young people, other aspects of built and natural geographies also are essential to their well-being, relationships, and belonging, from playgrounds to soccer fields to the density of their streets. So, while scholars often point to the legal geographies of immigrants’ contexts of reception, we argue that it also is critical to attend to how the physical landscapes of youths’ lives intersect with how, why, and where they construct spaces of belonging.

3. A New Model of Spaces of Belonging

We conceptualize belonging as the phenomenological experience of feeling recognized, valued, and securely cared for. Belonging encompasses freedom and safety, individual agency, and meaningful relationships with others. It means the right to hold onto pieces of one world even as you make your way in a new one (

Hooks 2008;

Jackson 1995). Spaces of belonging, in our framing, are sites that support young immigrants’ agency, writ large and small, and can become foundations for young people’s ability to thrive. While place is the organized, visible features of the built, social, and natural landscapes, spaces of belonging are the sites within these landscapes where immigrants find sources of care, freedom, power, and room to act. Spaces of belonging may be found in the literal or metaphorical borderlands, where nations and cultures bleed into each other (

Anzaldúa 2012). However, they may also take place firmly on one side of these borders or the other, in public, private, and virtual arenas, in schools and homes, on sports fields and city corners, in cafés and places of worship, in chat groups or on social media, or anywhere immigrant children, youth, and families join and create spaces of inclusion, connectedness and belonging.

Immigrant youth, however, carry a wide range of social locations, statuses, and identities. These aspects of young people’s identities differently enable and constrain participation in spaces of belonging (e.g.,

Canizales 2021;

Gonzales and Ruszczyk 2021;

Rodriguez 2020). A long legacy of exclusionary ideologies undergirds U.S. immigration policies, which means that immigrant youth from stable economic backgrounds are more likely to have access to authorized immigration (

Gonzales and Ruszczyk 2021;

López 2021). Even if these young people become undocumented after overstaying a visa, there are more pathways to regularizing status for children and youth who enter with inspection, as opposed to migrant youth who cross borders by land clandestinely. Therefore, while being undocumented can function as a master status, an overwhelming aspect of identity and daily experience, race, class, place, age, and gender all factor into how immigrant young people navigate their lack of legal status (

Abrego and Schmalzbauer 2018;

Dreby et al. 2020;

Gonzales and Burciaga 2018). Gender is also a powerful mediator of immigrant youth’s experiences. For instance, Central American youth who migrate to the United States on their own are more likely to be young men striving to meet economic obligations, while Mexican girls find their migrations determined by patriarchal family structures (

Canizales 2023;

Diaz-Strong and Gonzales 2023;

Soto 2018). Once in the United States, immigrant youth confront entrenched racial hierarchies that deny immigrant youth of color, especially Latinx and Black young people, equal opportunities for education and healthy living environments and leave them contending with low expectations from teachers and excessive surveillance from police (

Gonzales 2015;

Penn 2021;

Rios 2011). Theorizing spaces of belonging requires attending to the intersections between young immigrants’ various identities, and how these identities, in their homelands and arrival destinations, shape their ability to grow and thrive in their new communities.

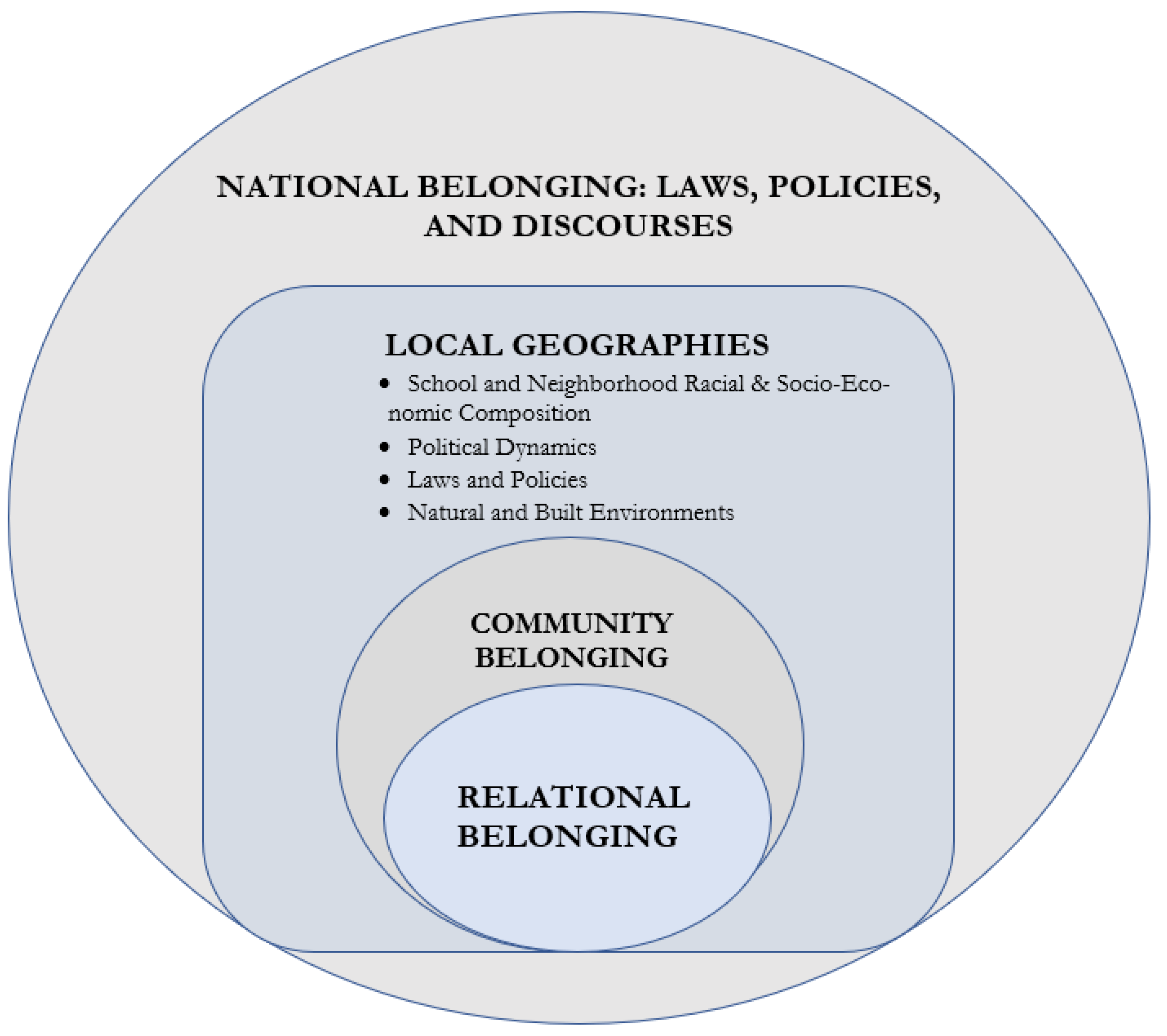

To capture the multilevel nature of spaces of belonging, we offer a model to distinguish between relational, community, and national levels of inclusion (see

Figure 1). We intentionally situate relationships at the center, as secure relationships can provide young people with a critical foundation for healthy social and emotional development. Community spaces of belonging surround these relational spaces, influencing and being influenced by the interpersonal connections immigrant youth form in their families, schools, churches, and places of worship, among others. We then depict the local geographies of belonging that are most relevant to young migrants’ construction of spaces of belonging. As we describe above, these include racial and socio-economic demographics, political composition, family laws and policies, and the built and physical features of children’s neighborhoods. These local geographies can function to insulate relational and community spaces of belonging but can also filter anti-immigrant laws and discourses into the intimate spaces where immigrant youth build relationships and engage in their communities. Finally, the national dynamics that shape belonging are portrayed at the outer layer of the model as a reminder that even though these discourses might be abstract for young people, they are inseparable from local experiences of belonging.

We recognize that in practice, these layers are not so clearly bounded as we depict in

Figure 1. Yet by teasing out these different levels of belonging, and by articulating how and why local geographies shape young migrants’ experiences in the United States, we hope to offer a useful conceptual tool to help scholars, policymakers, and practitioners make sense of pathways to inclusion for immigrant youth. In what follows, we define and conceptualize each layer of our model, situating young immigrants’ agency as they form and join spaces of belonging as a powerful force in constructing more inclusive communities.

4. Relational Spaces

Caring relationships are essential to meaningful belonging. Through their relationships with other children, loving family members, and other trusted adults, migrant youth have the opportunity to see themselves as valued, recognized members of their community. Often, the family is the first site of belonging for immigrant young people. Social scientists have measured how dimensions of immigrant parents’ identities or social positions influence children’s outcomes, from educational attainment to ethno-racial identification to immigration status and citizenship (e.g.,

Kim et al. 2020;

Langenkamp 2019;

Lareau 2011;

Yoshikawa and Kalil 2011). However, what if we reimagined immigrant families not only as sites of reproduction of inequalities or social mobilities but as spaces of belonging, inclusion, and safety? This reframing reshapes how we think about parent-child relationships, siblinghood, and connections with extended kin. Rather than seeing these relationships through the lens of the outcomes they produce, we could see them as opportunities for attachment and integration for immigrant youth and as powerful contributors to their sense of belonging. We could better understand how immigrant families help young people navigate and resist the racialized exclusions reified by U.S. immigration law. In addition, we could think expansively about family and learn how immigrant families reconfigure hegemonic organizations of family roles to provide care for immigrant children (

Bruhn and Oliveira 2022;

Delgado 2020). Of course, not all families are spaces of belonging, especially given the intergenerational trauma caused by forced migration, which can strain families’ coping mechanisms. Some immigrant children, like all children, contend with addiction, instability, and violence in their homes, and these struggles can strip away the family’s function as a space of relational belonging. In addition, these personal and social spheres are at times disrupted by hostile and exclusionary contexts that transform these spaces into spaces of vulnerability (

Gonzales et al. 2020). However, by centering on relational spaces of belonging, we encourage scholars, across methodological approaches, to think critically about what enables families to become central sites of belonging and what barriers exist as immigrant young people strive to foster the relationships that support a sense of belonging.

Beyond the family, immigrant youth encounter schools where they have uneven access to relationships that provide a strong foundation for belonging. Classrooms have long been unequal spaces of inclusion for immigrant children, where they have been castigated for speaking their own language, tracked into low-level classrooms with inadequate curriculum, or punished for infractions that are ignored when committed by their white, U.S.-born, middle-class counterparts (

Gonzales et al. 2015;

Skiba et al. 2014). However, schools can also be caring, vibrant spaces where young immigrants are honored and welcomed (

Sepulveda 2012;

Suárez-Orozco et al. 2008). When teachers engage in translanguaging with students, when they celebrate students’ families and cultural practices, and when they acknowledge the strengths, assets, and knowledge, alongside the trauma and hardship that children experience with migration, they create spaces where meaningful relationships flourish. Alongside relationships with teachers, schools can be powerful sites of friendships, offering young people the chance to build intra- and inter-ethnic friendships that can sustain them and help them navigate interpersonal and institutional discrimination (

Hondagneu-Sotelo and Pastor 2021;

Maghbouleh 2017). Young people’s friendships are not static, of course, shifting over time as children age and as they have spent more time in the United States. A kindergartener who came to the U.S. as an infant will have vastly different social needs from a ninth-grader who arrived a few months prior to the start of high school. We hope future research will take into account the evolving nature of relational spaces of belonging across developmental stages and time since migration.

In addition to caring interpersonal interactions, curricula that interrogate the histories and systemic injustice of the immigration system, racial hierarchies in the United States and transnationally, and immigrant activism foster relationships among students and teachers that are based on mutual understanding and respect. We are not naïve. We know that these kinds of relationships, pedagogies, and curricula are hard to come by, especially as extremists deny teachers the right to teach the history of race and racism in the United States. However, we also argue that the relationships immigrant youth form in such classrooms offer a profound sense of belonging, shaping youth’s aspirations, agency, and educational pathways.

Families and schools are among the most important institutions in young people’s lives. However, immigrant youth also regularly interact with healthcare, religion, and, for older migrant youth, places of employment. These sites have been underexplored in the literature on immigrant children and youth’s opportunities for inclusion. How might a trusting relationship with a pediatrician become an important institutional contact for a migrant young person? Or how might the relationships formed among immigrant youth at work become a critical source of recognition for young people who migrated without family support? Within these relationships, immigrant children are agentic social actors, engaging and connecting with people who can offer them care and support.

These relational spaces of belonging, whether in the family, school, or other institutional settings where immigrant young people find love and respect, are a means to resist the dehumanization inflicted by harsh U.S. immigration policies. Yet these relationships are not immune from the broader discourses about belonging and the politics that translate these discourses into restrictive subnational laws and policies. In this way, place becomes meaningful to the intimate relationships that young people form, even when these relationships are not contingent upon formal recognition or belonging vis-a-vis the state (such as a permanent, legal immigration status). Here, our conceptualization of place shines a light on how demographic, political, and physical geographies influence the intimate relationships immigrant young people develop. Take, as an example, the demographic landscape of the schools serving immigrant children. Picture, on the one hand, a traditional immigrant destination where previous generations of immigrants are now teachers, where multilingualism is normalized and celebrated, and where immigrant newcomers regularly encounter a racially diverse group of peers, teachers, and administrators, even if the schools are under-resourced. On the other hand, imagine a place where few immigrants have settled in recent decades, and where most members of the school community are white, U.S.-born, monolingual English speakers. In both cases, even if individual teachers provide care and nurturance, an immigrant child’s relational belonging will be situated in and shaped by the demographics of their school communities.

In addition to ethno-racial demographics, local legal geographies seep into young people’s relationships and access to relational belonging. In restrictive contexts where parents rightfully fear the threat of family separation through arbitrary, racialized immigration enforcement, young immigrants’ familial relationships are formed in a context of anxiety and stress. Parents, especially mothers, strive to offset this anxiety and protect their children from the consequences of these xenophobic laws (

Rendón García 2019). Yet when parents are forced to live with the threat of being torn apart, an especially cruel effect of U.S. immigration policy, it inherently shapes family dynamics and immigrant children’s ability to see their family relationships as a source of belonging. In contrast, when children have the opportunity to see their families protected and cared for through subnational policies that support immigrant families, especially policies that are inclusive of undocumented families, their relational belonging is buffered, at least to a degree, from racialized xenophobia. These tensions between the intimate spaces of relational belonging and policies at the local, state, and national level make clear that the geographies of young immigrants’ lives influence inclusion at every level.

Finally, participation in relational spaces of belonging varies according to children’s life stage at the time of migration and developmental needs over time. Young children arriving in a new nation will require different spaces of belonging to adolescents not only because they have been in the country longer and are likely to be proficient in the language, customs, and routines of their new home, but because they are at a different moment in their life course. For undocumented children, as well as children embedded in undocumented and mixed-status families, the process of awakening to illegality in childhood and adolescence makes it even more critical for them to find responsive, caring spaces of relational belonging to navigate the cruelty of U.S. immigration policy (

Gonzales 2011,

2015). While adult immigrants are more likely to experience fear because of a lack of legal status, children contend instead with stigma and shame (

Abrego 2011). Even young children draw on cues from their social world to piece together how illegality shapes their and their families’ lives. Here too, place matters. A rural community might provide young children access to outdoor spaces that meet their physical and emotional needs well. However, this same place as an adolescent might feel isolating to immigrant youth, especially if they do not encounter other young people who share their immigration status, ethnic identity, or linguistic practices.

By centering relational belonging, we foreground immigrant youth’s agency as they provide and seek recognition through caring relationships. We turn next to examine the communities in which these relational spaces of belonging are embedded.

5. Community Belonging

Relational belonging can enable immigrant youth to find spaces where they feel connected, cared for, and valued, whether in their families, schools, or other aspects of their lives (

Gonzales et al. 2020). However, as immigrant children adapt and grow over time, they also interact with their neighborhoods and communities, and through these encounters, find spaces that reinforce or undermine their sense of belonging. Through their daily routines, from attending a sports practice to accompanying a parent to the supermarket, young people witness the demographic, political, legal, and physical geographies of their communities. These geographic features inform how immigrant youth experience both the pervasive inequality that defines children’s experiences in the United States regardless of nativity or immigration status, and the specific anti-immigrant policies that supersede even robust inclusive measures at the local level. By depicting community belonging as surrounding relational belonging in our model, we hope to convey its importance and connection to immigrant young people’s relationships, opportunities, and aspirations in the United States.

No discussion of children’s lives in the United States is complete without interrogating the extreme levels of segregation that define U.S. cities, towns, suburbs, and schools. Contrary to popular understandings, white children are in fact the most segregated of all racial groups, with the average white student attending a school that is nearly 70% white (

Frankenberg et al. 2019). However, many immigrant children, especially those from Latin America, are racialized into the Latino category, regardless of individual self-perceptions of identity, and find themselves in highly segregated schools (

Frankenberg et al. 2019). While these schools are sometimes described as under-resourced, a more accurate analysis points to the fact that it is systemic, racial disinvestment, not the more neutral sounding “under-resourced” that leaves many poor schools serving immigrant children of color struggling to come up with the kinds of support all children and families deserve. The economic disinvestment and political marginalization of many low-income communities of color across the U.S. influence immigrant children’s opportunities and their belonging.

And yet, even within these arduous structural conditions, community spaces of belonging can and do thrive as young people use these spaces of belonging as a platform for everyday agency and choice. At the community level, even when geographies of belonging are shaped by inequality, local institutions can function as vital spaces where immigration status and marginalized racial identities become less salient in youth’s experiences. Schools are especially pivotal institutions at the community level, and at times can support immigrant children’s inclusion and value their linguistic and cultural assets, even as belonging in schools is rarely straightforward (e.g.,

Bartlett and García 2011;

Doucet and Kirkland 2021;

Gonzales et al. 2015;

Oliveira et al. 2020). Schools, however, tend to be frequent sites of study. Beyond schools, other organizations and spaces also provide powerful possibilities for belonging. Youth sports, for example, can be spaces of hierarchy, status, and competition. Nevertheless, they can also allow immigrant children to see themselves as connected to a community beyond the obligatory routines of school and family. Sports can function as spaces of agency, efficacy, and recognition and deserve more considered attention from scholars and educators striving to better understand how immigrant young people assert their belonging in their communities (

Trouille 2021). Athletics, of course, are only one example of these community-level spaces that enable a sense of belonging and a space where gender can be particularly salient for youth participation. Afterschool programs, religious schooling, and community arts organizations are other community-level spaces where immigrant young people find connection and recognition (

Vega 2023).

It is not that these spaces are automatically spaces of belonging. Rather, these kinds of programs can be generative spaces for young people across nativity, in part because they are often more flexible than schooling and offer children independence beyond the family. For immigrant and native-born youth alike, they can be spaces where young people learn to contest the systemic racism that perpetuates pervasive racial and economic inequalities. These dynamics vary as young people grow, with their needs for community belonging changing as they move from childhood to adolescence and beyond. Attending closely to how young immigrants use these spaces to foster their own and others’ sense of belonging widens the lenses we use to understand young immigrants’ agency and creativity as they integrate into their communities over time and developmental stage.

Community spaces of belonging are deeply rooted in the built and natural environments where immigrant children reside. Whether a child has access to safe public spaces to play or whether other children in these spaces share their ethnic, linguistic, or racial identities, has implications for their ties to and sense of themselves within their communities. There is nothing inherently better or worse about a public city swimming pool versus, for example, a swimming hole in a rural community. Both offer opportunities for outside play, physical activity, and engaging with other children and families. However, if immigrant children are racialized as not-belonging, their ability to claim these spaces as their own is diminished. This is especially true in areas with a high level of immigrant surveillance, such as regions within 100 miles of the U.S.—Mexico border, including cities like San Diego and rural regions along the Rio Grande Valley (

Castañeda 2019). The impact of physical geographies may also increase in importance with climate change. Rising temperatures in cities, increasing forest fires, especially in the immigrant-dense state of California, and damaging tropical storms have the potential to rupture young migrants’ ties to community spaces of belonging. However, climate devastation might also produce new spaces of belonging as immigrant youth and communities organize and contest the unequal burden of an increasingly chaotic climate.

Attending closely to the intersections between physical place, demographic composition, and racialized illegality illuminates the landscapes of immigrant youths’ belonging. In our model, we situate the community level as surrounding the relationships that are so central to immigrant young people’s belonging. Clearly, in immigrant youth’s daily lives, the boundaries between relational and community belonging are not defined by a stark line. Yet we depict them as distinct to theorize how these two forms of spaces of belonging inform each other. Community spaces of belonging can protect and nurture relationships that form within them. In turn, these meaningful relationships, and the sense of care and recognition they produce, provide a foundation for community spaces that publicly and visibly assert young immigrants’ worth and inclusion. However, here too, geography mediates the function of community spaces of belonging in young people’s lives. To return to the driver´s license example, if young people live in rural places where these community spaces are spread out across long distances, and unauthorized immigrants cannot access driver´s licenses, children may not be able to participate in these spaces without enduring anxiety-producing drives. This reinforces their exclusion, rather than their belonging, shaping young people’s relationships within these community spaces. On the other hand, dense, urban destinations, particularly those with protective sanctuary ordinances, may ease the strain of accessing these spaces, from informal pick-up games of soccer to formal extracurriculars. However, if higher costs of living in these spaces necessitate the youths’ economic participation, young immigrants may not have the time to take part in these symbolically welcoming community spaces. In this case, looking beyond formal organizations to the informal spaces where young people nurture each other and recognize the complexity of navigating a new nation marked by pervasive racial and economic hierarchies is essential to make sure our understanding of community spaces of belonging is not limited to those with relative privilege.

Just as community spaces interact with relational belonging, community spaces of belonging are vital for mediating national migration policies which are filtered through the geographies that influence every layer of belonging. Through their participation in community spaces of belonging, young immigrants contest and remake national discourses. It is to these national spaces of belonging that we turn to next.

6. National Belonging

Spaces of belonging cannot be understood without considering the national-level policy and institutional contexts in which they are embedded. Policies and practices related to immigrants and immigration are subject to political winds and can change rapidly (

Silver 2018). The impact of these shifting contexts extends to family members of immigrants, documented or not, as changes in policy affect whole families and communities, regardless of whether one is a primary target of the policy (

Castañeda 2019;

Dreby 2015;

López 2021). As immigrant children and their families respond to these everchanging political realities, spaces of refuge, connection, and inclusion offer important protections to their dignity and sense of worth.

National policies and politics are abstract and configured in spaces of power often made inaccessible to young immigrants. However, although immigration laws and policies are opaque and complicated, even to keen observers of the law, immigrant youth are very aware of the concrete harm resulting from these laws. In addition, just as immigrant children’s needs for relational and community belonging evolve as they grow, their legal consciousness also develops over time, allowing immigrant youth to become sharply perceptive about the inequalities fostered by their (in)ability to access formal belonging to the United States (

Abrego 2011). Through the forms of inclusion fostered by relational and community spaces of belonging, immigrant youth internalize, replicate, and challenge both anti-immigrant policies and racialized, xenophobic discourses (

Abu El-Haj 2007;

Flores 2021).

Yet while immigration policy officially remains a federal responsibility, local geographies of belonging act as a filter between national inclusion and the relational and community spaces of belonging constructed by young immigrants and the adults that care for them. These geographies can become powerful protectors of belonging, even when hostility towards immigrants is woven into U.S. immigration and social policy. As an example, consider a traditional immigrant destination in a state with inclusive policies, including limited cooperation with the federal deportation machine, driver’s licenses, and access to higher education. In such a place, young immigrants could be surrounded by co-ethnic networks and immigrant-serving organizations reflecting the youths’ racial and linguistic identities. Immigrant children could find others who struggle under the weight of anti-immigrant national laws, easing their isolation or shame about their own families’ challenges. These factors can offer protection from the exclusion young people feel in the face of limited access to national belonging. However, when economic and physical geographies, even in places that have inclusive policies, are marked by inequality, the consequences of systemic, racist disinvestment from Black and immigrant neighborhoods are rendered clear as immigrant young people strive to belong. Even formal inclusion, including citizenship, does not by itself transform immigrant youth’s negotiation of these profoundly unequal landscapes. In this way, the geographies of belonging shape immigrant children’s perspectives of their communities, their value to the nation-state, and their access to the promise of opportunity in the United States.

Even as young immigrants embed themselves in U.S. towns and cities, their frames of reference, relationships, and identities are often transnational, extending across arbitrary, militarized borders erected by histories of violence (

Dyrness and El-Haj 2020). Understanding national-level dynamics of belonging and exclusion requires us to attend to these cross-national practices. This remains true even if immigrant youth never leave the confines of the United States once they arrive, as is common because of harsh immigration laws that hinder families’ ability to nurture transnational relationships (

Abrego 2014;

Bruhn and Oliveira 2022). These transnational ties are also shaped by anti-immigrant policies, such as the anti-Central American rhetoric shaping Mexico’s immigration laws, as well as anti-indigenous racism that shapes linguistic, educational, and social policies throughout Central and South America (

Alvarado et al. 2017;

Asad and Hwang 2019). As young immigrants navigate and build spaces of belonging, they do so within transnational contexts, even if they remain physically in the United States.

Whether through nationally visible protests or quotidian acts of care, immigrant youth are not passive recipients of policy and formal inclusion (

Escudero 2020;

Gonzales 2007;

Nicholls 2013;

Seif 2004). Young immigrants and their allies advocate and resist, pushing politicians and policymakers to construct formal pathways to belonging. In this way, we see a dynamic interplay between the levels of belonging that we argue are central to immigrant youths’ well-being and opportunities. Nurturing relationships, in the family, in schools, and with other peers and adults, envelop immigrant young people in care and intimate belonging. Community spaces where young immigrants see themselves as recognized members create more visible opportunities for belonging and essential ties beyond the close-knit relationships that anchor children’s belonging as they settle into a new nation-. In turn, these relational and community spaces support youths’ sense of agency and entitlement to formal belonging, even as they acknowledge and contend with racism, illegality, and inequality.

Across diverse geographies and contexts, U.S. immigration policy creates inhospitable conditions for young immigrants and their families—from the fact that family reunification is contingent on wealth to the exclusion of undocumented immigrants from fundamental social programs like the Affordable Care Act. Even the most inclusive of policies in recent years, Deferred Action for Childcare Arrivals, has been plagued by the politics of belonging, expensive application fees, and fear of making oneself bureaucratically visible to the U.S. government. One institution, however, has remained a stalwart of formal inclusion across the United States: schools. For centuries, schools have been considered a stalwart of assimilation and integration for immigrant students, especially those racialized as non-white. This formal inclusion was reified in the 1982 Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe, which forbids schools from excluding children from K-12 schools based on their or their parents’ immigration status.

However, just as it once seemed unimaginable that we would return to an era when women’s basic autonomies were denied, so too has it seemed improbable that we could exclude undocumented children from education, enumerated by the United Nations Human Rights Commission as a universal human right. Yet with U.S. governors threatening to challenge Plyler and a right-wing Supreme Court amenable to overthrowing precedent and dismantling basic protections, this is no longer unthinkable. If Plyler were to be overturned—and we fervently hope that it remains the law of the land—it would be left to cities and states to determine whether immigrant students, with or without lawful status, could access schooling. Schooling and national belonging are profoundly interconnected, and yet this could come to be determined by local geographies. In turn, these local geographies would become even more important in generating or constraining immigrant children’s participation in spaces of belonging.

7. Discussion

In this paper, we argue that spaces of belonging at the relational, community, and national level are as central to immigrant youths’ experiences of settlement as the exclusionary laws and policies that constrain opportunities. Through a new model of spaces of belonging, we demonstrate how political, legal, social, and physical geographies fundamentally shape how migrant youth and their families construct and access spaces of belonging. We show how these features of place are woven into relational and community spaces, shaping young people’s interactions with each other, with caring adults, and with the organizations and institutions that are essential to their incorporation into the United States. These local geographies, from the built environment to the racial and ethnic demographics of children’s schools, also mediate broader national discourses about immigration.

Our conceptualization of spaces of belonging has several important methodological, theoretical, and practical implications. First, spaces of belonging, and the young immigrants who construct and participate in these spaces, evolve over time. Echoing previous longitudinal research, we call for increased attention to time as a critical dimension in the lives of immigrant children and their families (

Cohen 2018). For qualitative researchers, staying in communication with immigrants whose lives are often made precarious by legal and economic exclusions, can be ethically and practically challenging. However, designing studies to capture changes over time can enliven our understanding of belonging, place, and migration. For instance, in our own respective ethnographic work, we each spent several years developing relationships with participants, which facilitated connections with undocumented immigrants over time. These relationships meant that when significant legal and social changes occurred, including the implementation of DACA, the election of Donald Trump, and the COVID-19 pandemic, we were poised to document how immigrants constructed and engaged with spaces of belonging during these tumultuous moments.

1 Turning our attention to the influence of time also highlights the relationships between spaces of belonging and place. From the changes wrought in immigrant neighborhoods because of gentrification to the impact of droughts induced by climate change on migrant workers to growing immigrant populations in previously predominantly white regions, how places evolve over time matters for how, when, and why spaces of belonging influence immigrant youth’s integration in their new lands.

Second, in demonstrating how the geographies of belonging influence how immigrant youth create spaces of inclusion, we offer new lenses to make sense of how immigrant young people transform the places they weave themselves into over time and across the different stages of their lives. Migration reconstructs the social, economic, cultural, and political fabric of receiving states in a process of two-way integration, even as enduring power structures may limit the reach of these changes (

Bloemraad and Sheares 2017;

Klarenbeek 2019). However, the focus is so often on adult immigrants’ influence on their new communities, even as the presence of immigrant children and youth also reconfigures local communities. These transformations come in part through the construction of spaces of belonging, where immigrant youth, their families, and their allies find the material and psychological resources necessary to remake their new environments. Immigrant children reshape and rebuild the worlds they live in, even when they have minimal state-sanctioned power. As immigrant children join and participate in spaces of belonging, they become woven into the landscape of their communities, changing the geographies, economies, demographies, and cultures of their contexts of reception. The model of belonging we provide in this paper could be a useful guide to future scholarship that strives to make sense of these evolving landscapes of inclusion, at the relational, community, and national level. Because children are never static, we hope that this future research will encompass how developmental trajectories influence how immigrant children, youth, and adults navigate these varied spaces.

Third, our model of spaces of belonging encourages us to look beyond the broad public moments of inclusion or exclusion for immigrant youth, whether large collective protests by the immigrant rights movement or executive orders from presidential administrations. Spaces of belonging, especially at the relational and community level, are often intimate and rarely visible to the public eye. Building on prior research that documents these quotidian moments of belonging, from skits enacted in a college access program (

Flores 2021) to participation in an Aztec dance circle (

Gonzales 2015) to classroom conversations about the impact of anti-immigrant policies (

Jaffe-Walter et al. 2019), these day-to-day markers of inclusion are important counterpoints to the weight of illegality. Friendships among immigrant children, healthcare providers who attend respectfully to immigrant children and their families, school playgrounds where immigrant youth play and speak their language—all of these are possible and critical spaces of belonging, nested within both inclusive and restrictive legal geographies. Attending closely to belonging writ small, we can better understand young immigrants’ resilience and resistance in the face of anti-immigrant laws and xenophobic discourses that too often frame them as outsiders.

Finally, by attending to the intersections of spaces of belonging and place, this work speaks to practical problems and possible solutions for immigrant young people, their families, and the educators, healthcare providers, and other community members who support them. Fostering belonging is often in the details, in the careful attention to the constraints of immigrant families’ lives. An after-school music program in a densely populated city in a state without driver’s licenses for undocumented residents, for instance, could be a powerful space of belonging for immigrant children at the community level. However, this program can only be transformed into a space of belonging with careful attention to transportation, the lack of quiet practice places in crowded, shared apartments, and the cultural meanings of music across borders. A group of high school students organizing against gun violence might be a place where relational belonging about immigrant and U.S.-born peers is fostered. If the politics of the state, however, are rife with anti-immigrant politics, immigrant students might be hesitant to take part in public activism regardless of whether they are authorized to be in the United States. In this case, careful adult guidance could help young people sort through these complicated ethical questions, supporting the kinds of interactions and care that can grow into relational belonging. Our aim is not to generate an exhaustive list of programs and possibilities that could engender belonging across relational, community, and national levels. Instead, we hope to point to how this work of theorizing the geographies of belonging can have a meaningful and positive impact on the lives of immigrant young people, their families, and their communities.

8. Conclusions

The young immigrants who arrived in Somerville throughout the 2021–2022 year have now begun to find their way in their new city. They are starting to learn English and gain familiarity with the rhythms and routines of U.S. schools. Some of them will have built relationships with each other, with teachers, or with family members they are reuniting with after migration. These relationships will rarely be easy, but they also offer opportunities for immigrant youth to be recognized and cared for, to be seen as whole, complex, deserving children. Beyond these relational spaces of belonging, these newly arrived youth are making their way into their new community, splashing in the sprinklers at local parks, baking for a church event alongside an aunt, and participating in summer programs throughout the city. Many will not find a way to permanent U.S. belonging, with injunctions against DACA in place and little political will to legislate broad access to citizenship. However, some will eventually have access to naturalization, and regardless of legal immigration status, these young people will nonetheless contribute to remaking our national landscapes of migration. By offering a model of spaces of belonging at the relational, community, and national level, and by shining a light on how local geographies are woven into these spaces, we offer a new lens on the dynamics and processes through which immigrant youth claim their right to be included, recognized members of their families, schools, communities, cities, and nation-states.