Drawing Together in Scotland: The Opportunities and Challenges for Young Refugees within a ‘Relational Wellbeing’ Approach to Integration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

To me, Scotland is like a second chance God is giving me in Scotland, and I’ve been taking advantage of it. To me, Scotland would be like the start of my successful story. When I tell my story to my future kids or grandkids I’ll be like, “Once upon a time”, and I start with Scotland…Because the things I got here I could never dream of back home. … Connections are very important to have in life. Scotland has given me plenty of that.

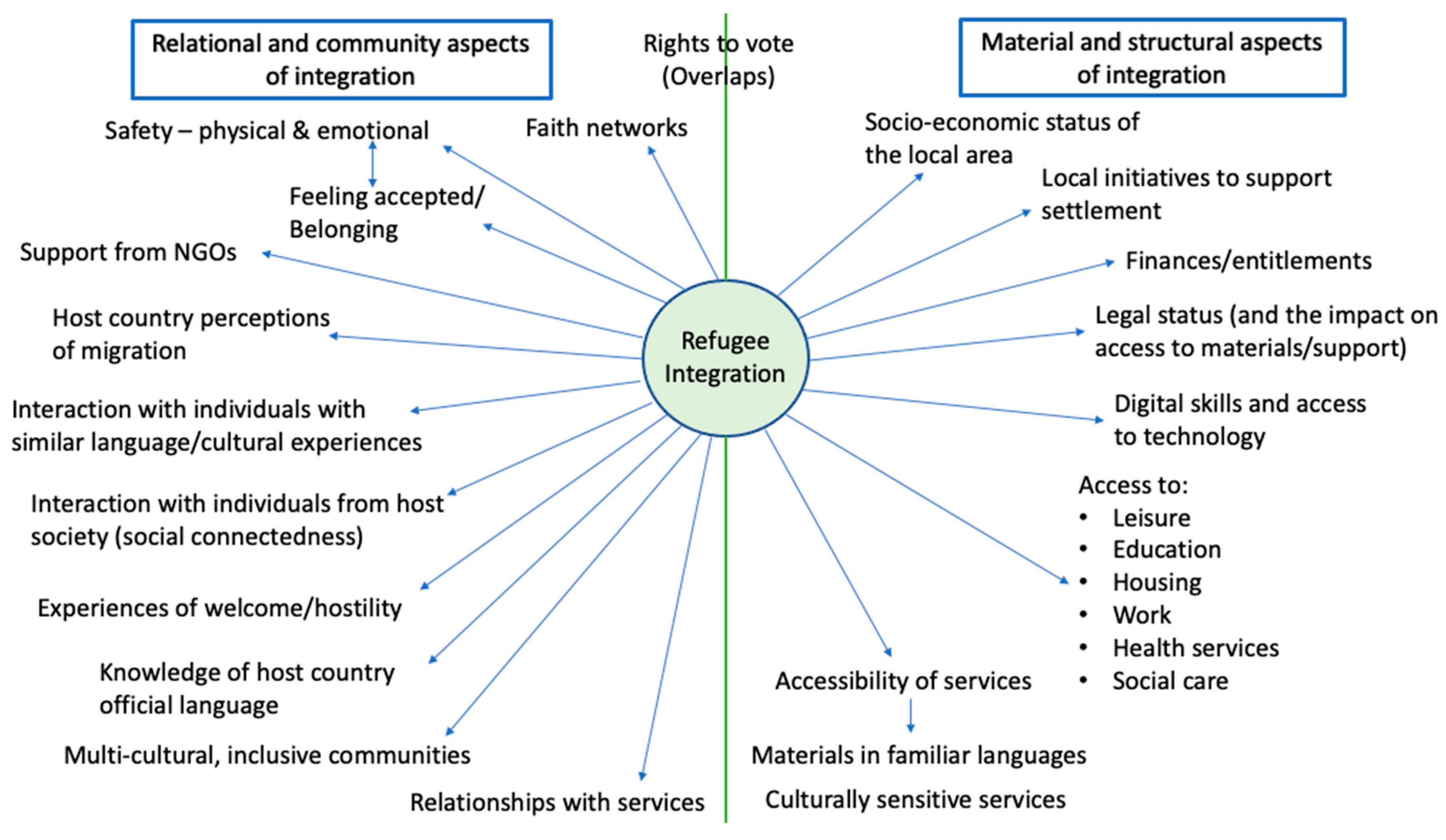

2. Refugee Integration and Its Multiple Dimensions

3. The Drawing Together Project, Relational Wellbeing and Refugee Integration

- What does it mean to become or be Finnish, Norwegian, or Scottish for young refugees and the people whom they value in life?

- What local or national resources, cultures, and behaviours make integration work, both for young people who are refugees, and hosts who are prepared to receive them?

- First, people ‘having enough’ in terms of their material needs, and achieving stability through, for example, the provision of education and employment, housing, health and social care services.

- Second, people ‘being connected’ to others and exercising their relational rights and responsibilities within sustaining communities of protection and care.

- Third, ‘feeling good’ subjectively, not just in relation to others and to resources, but also in relation to their environments and faith systems.

Methods and Data Analysis

4. Drawing Together in the Context of Scottish and UK Approaches to Integration

5. Relational Wellbeing and Scottish Civil Society

6. Child-Focussed Policy and Relational Wellbeing

7. Drawing Together, Integration and Relational Wellbieng

7.1. HAVING ENOUGH, and the Material Dimensions of Integration

I went straight into the restaurant and asked them for a work. ‘Do you guys have any work for me?’ He said, ‘Come back tomorrow’. And then when I come back the day after, the boss, the owner was there. And I said to him, ‘I’m looking for work. The dishwasher was leaving. They said to me, ‘We have you a dishwasher to start with, do you want it?’ It was a hard job, I was doing it, I was doing it for two months … I was working very hard, they look at what I was doing, I was coming on time, everything. So, he give me the chance, I explained to him all my situation, my English is not good enough, my first time in this country, I don’t have work experience. Even I say this, he give me the opportunity, he say, ‘Not a problem, everyone has their situation’

And then she was trying always to make me happy. I remember my teeth was like a rabbit, like you know, was quite a bit out, and then when I laugh with her, I was hiding my teeth like this. Then she say to me, “Why you hiding your teeth because they are so beautiful, why are you hiding your teeth?” Because I said to her, I’m not comfortable when I laugh because my teeth is quite out, and when I laugh, I feel like I have rabbit teeth … And then she’d say to me, “Let’s go to the dentist to do a brace.

7.2. BEING CONNECTED and Being Relational

The word belonging, for me, is crucial … because I think what teachers on this programme always try to create, is this sense of connection, not just between the teacher and the young person[who is a refugee], but between the young people and each other … The connection that they can find with each other is something that can sustain them when they’re not in the classroom, when they’re not in college, when things have moved on in their life. To make those relationships with each other and to see how they can support each other … Because my sense is that very often young people feel that everything is being done to them and for them, whereas when they are able to support each other, they’re doing it for each other. They’re bringing something. They’re offering something …

It means for me church, when I go church, so I can understand singing and if I want to be quiet, so I can be quiet, I can read bible, to teach people and to pray. Yeah, that’s why its important for me to go church, to understand deep.

If you ask a bird in a cage, “How do you feel?”, what would the bird tell you? You’ve got freedom outside but you’re in the cage, you cannot go outside [because of Covid], … I just look out of my window because there is a nice park out of my window, I can see the freedom outside, I can’t use that freedom because of this COVID19 which is separating myself from my outside communityBut we stay on the positive side and encourage each other, being part of each other life, to feel that way, and to share that loneliness together, so not being able to face-to-face talk.

7.3. FEELING GOOD and the Subjective Aspects of Integration

[X country] people they are humble … In [this city] in the middle of the night I can walk by myself, no one can ask me, and [] people everywhere they say, “Hi mate,” make you feel like safety ... In my country whenever you see someone you have to say salaam alaykum. Like here in [this country] you say hi, it’s the same as salaam alaykum. People here are good …

Yeah, I like this picture, it reminds me of when I first come to this country. When I came here it was so strange this country and I received from my teacher. So, she helped me a lot and the way I am here, and I am able here to learn from people and how I learn from society. I think that it represents her, how she likes helping people to encourage them to go to community, to people, get on well with them, to get to know them, to find yourself, be independent, to be freedom. Just makes you stronger. And every time I look at this picture, it makes me very stronger and makes me very happy.

So, like at the beginning I didn’t know what I’m going to be, so I imagined myself and saw my future by these people, so I can help people in the future, I can give them something, hope …

8. Conclusions

Some of the trees are very old and brokenthey lean on other trees and they hold onfor me it’s absolutely amazing,it’s not just human being that can help each other,look at nature, the trees are encouraging, holding each other’s weightIt’s as if they were saying“Yes, don’t worry, I’m holding you, we’re not finished here”

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2004. Indicators of Integration: Final Report. Home Office Development and Practice Report 28. London: Home Office. [Google Scholar]

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. Understanding Integration. Journal of Refugee Studies 21: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John W. 1997. Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology 46: 5–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtice, Sir John, and Ian Montagu. 2018. Do Scotland and England & Wales have Different Views about Immigration? London: Natcen. Available online: https://natcen.ac.uk/our-research/research/do-scotland-and-england-wales-have-different-views-about-immigration/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Davidson, Neil, and Satnam Virdee. 2018. Understanding racism in Scotland. In No Problem Here: Racism in Scotland. Edited by Neil Davidson, Minna Liinpaa, Satnam Virdee and Maureen McBride. Edinburgh: Luath Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ekoh, Prince Chiagozie, and Kathleen Sitter. 2023. Timelines, convoy circles and ecomaps: Positing diagramming as a salient tool for qualitative data collections in research with forced migrants. Qualitative Social Work 2023: 14733250231180321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Catrin. 2020. The Arts of Integration: Scottish Policies of Refugee Integration and the Role of the Creative and Performing Arts. Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena. 2020. Refugees in a Moving World. Tracing Refugee and Migrant Journeys across Disciplines. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galandini, Silvia, Gareth Mulvey, and Laurence Lessard-Phillips. 2019. Stuck Between Mainstreaming and Localism: Views on the Practice of Migrant Integration in a Devolved Policy Framework. Journal of International Migration and Integration 20: 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, Matthew J. 2004. The Ethics and Politics of Asylum. Liberal Democracy and the Response to Refugees. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH). 2022. Understanding Glasgow. The Glasgow Indicators Project. Available online: https://www.understandingglasgow.com/indicators/poverty/overview (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Hartley, Leslie Poles. 1953. The Go-Between. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Ann. 1995. Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services 76: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, Mary, Helen Crowley, and Nick Mai. 2008. Immigration and Social Cohesion in the UK: The Rhythms and Realities of Everyday Life. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Available online: https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/2230-deprivation-cohesion-immigration.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Independent Care Review. 2020. The Promise. Available online: https://www.carereview.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-Promise.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Katwala, Sunder, Steve Ballinger, and Matthew Rhodes. 2014. How to Talk about Immigration. London: British Future. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, Ravi K. S. 2014. Protecting Asylum Seeking Children on the Move. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 30: 83–104. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-europeenne-des-migrations-internationales-2014-1-page-83.htm (accessed on 14 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kohli, Ravi K. S., and Mervi Kaukko. 2018. The Management of Time and Waiting by Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Girls in Finland. Journal of Refugee Studies 31: 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrone, David. 2017. The New Sociology of Scotland. London: SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Ndofor-Tah, Caroline, Alison Strang, Jenny Phillimore, Linda Morrice, Lucy Michael, Patrick Wood, and Jon Simmons. 2019. Home Office Indicators of Integration Framework 2019, 3rd ed. London: Home Office. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson, Marcus, and Umut Korkut. 2022. The Making and the Portrayal of Scottish Distinctiveness: How does the Narrative Create its Audience? International Migration 60: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillimore, Jenny. 2021. Refugee-Integration-Opportunity Structures: Shifting the Focus from Refugees to Context. Journal of Refugee Studies 34: 1946–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytter, Mikkel. 2019. Writing Against Integration: Danish Imaginaries of Culture, Race and Belonging. Ethnos 84: 678–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, Gillian. 1998. Inner and outer worlds: A psychosocial framework for child and family social work. Child & Family Social Work 3: 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. 2013. Scottish Government Equality Outcomes: Religion and Belief Evidence Review; Scottish Government Research. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-equality-outcomes-religion-belief-evidence-review/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Scottish Government. 2018. New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018–2022. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/new-scots-refugee-integration-strategy-2018-2022/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Scottish Government. 2020. The Environment Strategy for Scotland: Vision and Outcomes. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/environment-strategy-scotland-vision-outcomes/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Scottish Government. 2022. Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC): Policy Statement. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/getting-right-child-girfec-policy-statement/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Scottish National Party. 2022. What Is the SNP’s Policy on Immigration? Available online: https://www.snp.org/policies/pb-what-is-the-snp-s-policy-on-immigration/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- The Guardian. 2021. ‘A Special Day’: How a Glasgow Community Halted Immigration Raid. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/may/14/a-special-day-how-glasgow-community-halted-immigration-raid (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE). 2021. UK Asylum Policy After Brexit. Available online: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/explainers/asylum-policy-after-brexit/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/crc.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 1951. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Geneva: UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- Valluvan, Sivamohan. 2016. Conviviality and Multiculture: A Post-integration Sociology of Multi-ethnic Interaction. Young 24: 204–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Sarah C. 2008. But What Is Wellbeing? A Framework for Analysis in Social and Development Policy and Practice. Bath: University of Bath. Available online: https://people.bath.ac.uk/ecsscw/But_what_is_Wellbeing.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- White, Sarah C., and Shreya Jha. 2020. Therapeutic culture and relational wellbeing 1. In The Routledge International Handbook of Global Therapeutic Cultures. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 203–14. [Google Scholar]

- White, Sarah C., and Shreya Jha. 2023. Exploring the Relational in Relational Wellbeing. Social Sciences 12: 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohli, R.K.S.; Sullivan, P.; Baughan, K. Drawing Together in Scotland: The Opportunities and Challenges for Young Refugees within a ‘Relational Wellbeing’ Approach to Integration. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120666

Kohli RKS, Sullivan P, Baughan K. Drawing Together in Scotland: The Opportunities and Challenges for Young Refugees within a ‘Relational Wellbeing’ Approach to Integration. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(12):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120666

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohli, Ravi K. S., Paul Sullivan, and Kirstie Baughan. 2023. "Drawing Together in Scotland: The Opportunities and Challenges for Young Refugees within a ‘Relational Wellbeing’ Approach to Integration" Social Sciences 12, no. 12: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120666

APA StyleKohli, R. K. S., Sullivan, P., & Baughan, K. (2023). Drawing Together in Scotland: The Opportunities and Challenges for Young Refugees within a ‘Relational Wellbeing’ Approach to Integration. Social Sciences, 12(12), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120666