Adapting to Change: Investigating the Influence of Distance Learning on Performance in Italian Conservatories

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Music and COVID-19

2.2. Satisfaction

2.3. Performances

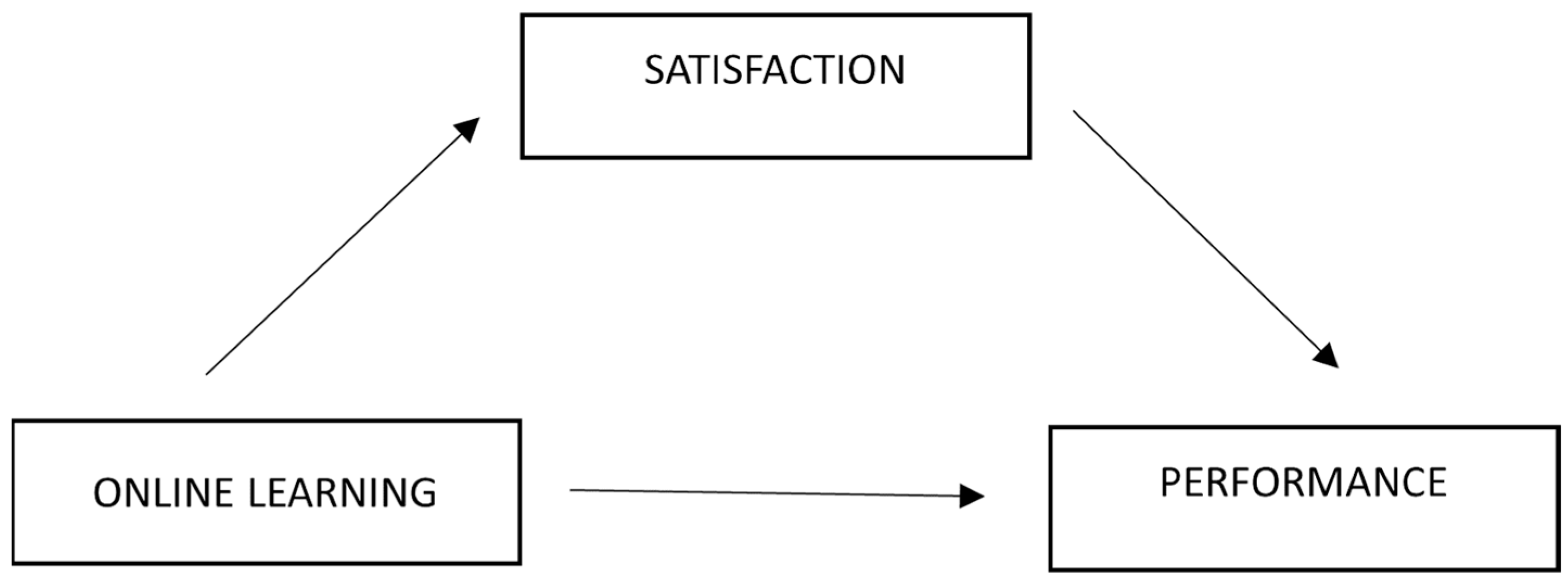

2.4. Aim of the Study and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Method

3.2. Data collection Process

3.3. Sample Characteristics

3.4. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Model Testing

5. Discussion

6. Limits, Implications, and Future Studies

6.1. Limits

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ahshan, Razzaqul. 2021. A framework of implementing strategies for active student engagement in remote/online teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences 11: 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMahdawi, Manal, Salieu Senghore, Horia Ambrin, and Shashidhar Belbase. 2021. High school students’ performance indicators in distance learning in chemistry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences 11: 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusharraf, Norah, and Shabir Khahro. 2020. Students satisfaction with online learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET) 15: 246–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloran, Erick T., and Jenny T. Hernan. 2021. Course satisfaction and student engagement in online learning amid COVID-19 pandemic: A structural equation model. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 22: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuony, Mohamend A., Rehab EmadEldeen, Marwa Farghaly, Noha El-Bassiouny, and Ehab K. Mohamed. 2021. The factors affecting student satisfaction with online education during the COVID-19 pandemic: An empirical study of an emerging Muslim country. Journal of Islamic Marketing 12: 631–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Muhammad Tariq, and Roshan Ali Teevno. 2021. Nonverbal Communication (NVC) and teacher presence in collaborative online learning. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government 27: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, Sameera, Asif Mahmood, Saima Saleem, Shaha Ali Murtaza, Sana Hassan, and Edina Molnár. 2023. The Contribution of Learner Characteristics and Perceived Learning to Students’ Satisfaction and Academic Performance during COVID-19. Sustainability 15: 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garrido, Diego, and Josep Gustems-Carnicer. 2021. Adaptations of Music Education in Primary and Secondary School Due to COVID-19: The Experience in Spain. Music Education Research 23: 139–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garrido, Diego, Josep Gustems-Carnicer, and Adrien Faure-Carvallo. 2021. Adaptations in Conservatories and Music Schools in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Instruction 14: 451–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Patricia Shehan, David E. Myers, and Edward W. Sarath. 2016. Transforming music study from its foundations: A manifesto for progressive change in the undergraduate preparation of music majors. In Redefining Music Studies in an Age of Change. London: Routledge, pp. 59–99. ISBN 9781315649160. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh, Joseph, Stephen Jacquemin, and Christine Junker. 2023. A look at student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Quality Assurance in Education 31: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Bo, Jinlu Sun, and Yi Feng. 2020. How have COVID-19 isolation policies affected young people’s mental health?–Evidence from Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Lee, and Chi Ying Lam. 2021. The worst is yet to come: The psychological impact of COVID-19 on Hong Kong music teachers. Music Education Research 23: 211–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisadza, Carolyn, Matthew Clance, Thulani Mthembu, Nicky Nicholls, and Eleni Yitbarek. 2021. Online and face-to-face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. African Development Review 33: S114–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Ted M., Christopher S. Callam, Noel M. Paul, Matthew W. Stoltzfus, and Daniel Turner. 2020. Testing in the time of COVID-19: A sudden transition to unproctored online exams. Journal of Chemical Education 97: 3413–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubney, Alison, and Martin Fautley. 2020. Editorial Research: Music education in a time of pandemic. British Journal of Music Education 37: 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, Robert F. 2016. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Di Palma, Davide, and Patrizia Belfiore. 2020. La trasformazione didattica universitaria ai tempi del COVID-19: Un’opportunità di innovazione? Formazione & Insegnamento 18: 281–93. [Google Scholar]

- Faize, Fayyaz Ahmad, and Muhammad Nawaz. 2020. Evaluation and improvement of students’ satisfaction in online learning during COVID-19. Open Praxis 12: 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froment, Facundo, and Manuel De Besa Gutiérrez. 2022. The prediction of teacher credibility on student motivation: Academic engagement and satisfaction as mediating variables. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English Ed.) 27: 149–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuad, A. Jauhar, and Pranita Andhinasari. 2021. Improving Student Learning Outcomes During The COVID-19 Pandemic Using Learning Videos and E-Learning. EL Bidayah: Journal of Islamic Elementary Education 3: 102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiadini, Alessandro, Giulia Paganin, and Slvia Simbula. 2023. Teaching after the pandemic: The role of technostress and organizational support on intentions to adopt remote teaching technologies. Acta Psychologica 236: 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanti, Teresa, Clara De Vincenzi, Ilaria Buonomo, and Paula Benevene. 2023. Digital Transformation: Inevitable Change or Sizable Opportunity? The Strategic Role of HR Management in Industry 4.0. Administrative Sciences 13: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Teresa, M. Angeles. De La Rubia, Kajetan Piotr Hincz, M. Comas-Lopez, Laia Subirats, Santi Fort, and Gomez Monivas Sacha. 2020. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE 15: e0239490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgoretti, Başak. 2019. The use of technology in music education in North Cyprus according to student music teachers. South African Journal of Education 39: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, Khaldoun Mohammad, Ahmad M. Al-Bashaireh, Zainab Zahran, Amal Al-Daghestani, Samira AL-Habashneh, and Abeer M. Shaheen. 2021. University students’ interaction, Internet self-efficacy, self-regulation and satisfaction with online education during pandemic crises of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). International Journal of Educational Management 35: 713–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hash, Philip M. 2021. Remote Learning in School Bands during the COVID-19 Shutdown. Journal of Research in Music Education 68: 381–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, Ali Salah, Wid Akeel Awadh, and Alaa Khalaf Hamoud. 2020. Student performance prediction model based on supervised machine learning algorithms. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 928: 032019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Handrew. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Yumeng. 2020. Research on online teaching of music performance based on diversification and intelligence–take the online music teaching during the COVID-19 as an example. Paper presented at the 2020 International Conference on E-Commerce and Internet Technology (ECIT), Zhangjiajie, China, April 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hepşen, Okan. 2022. Conservatory Voice Department Students’ Opinions on Piano and Accompaniment Courses in The COVID-19. Gazi Üniversitesi Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 42: 1791–820. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, Ana Martínez. 2020. Online learning in higher music education: Benefits, challenges and drawbacks of one-to-one videoconference instrumental lessons. Journal of Music, Technology & Education 13: 181–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hickland, Maria M., Elianor R. Gosney, and Katie L. Hare. 2020. Medical student views on returning to clinical placement after months of online learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical Education Online 25: 1800981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabluk, Robert. 2023. Teaching Presence in Private Online Music Lessons. The Canadian Music Educator 64: 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Pradas, Santiago, Ángel Hernández-García, Julián Chaparro-Peláez, and José Luis Prieto. 2021. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior 119: 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhsan, Ridho Bramulya, Listya Ayu Saraswati, Brian Garda Muchardie, and Adrianto Susilo. 2019. The determinants of students’ perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction in BINUS online learning. Paper presented at the 2019 5th International Conference on New Media Studies (CONMEDIA), Bali, Indonesia, October 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaif, Zuheir N., Soheil Salha, and Bochra Kouraichi. 2021. Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: Students’ engagement. Education and Information Technologies 26: 7033–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khusniyah, Nurul Lailatul, and Lukman Hakim. 2019. Efektivitas pembelajaran berbasis daring: Sebuah bukti pada pembelajaran bahasa inggris. Jurnal Tatsqif 17: 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, Ivans, Jelena Anđelković Labrović, Nikola Petrović, and Ivana Kužet. 2021. Recognizing predictors of students’ emergency remote online learning satisfaction during COVID-19. Education Sciences 11: 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Weiyi, Sied Imran Zaman, Sobia Jamil, and Sharfuddin Ahmed Khan. 2023. Students engagement in distant learning: How much influence do the critical factors have for success in academic performance? Psychology in the Schools 60: 2373–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucisano, Pietro. 2020. Fare ricerca con gli insegnanti. I primi risultati dell’indagine nazionale SIRD “Per un confronto sulle modalità di didattica a distanza adottate nelle scuole italiane nel periodo di emergenza COVID-19”. LLL-Lifelong Lifewide Learning 17: 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mandasari, Berlinda. 2020. The impact of online learning toward students’ academic performance on business correspondence course. EDUTEC: Journal of Education and Technology 4: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, Rosalba, Samuele Calzone, and Letizia Cinganotto. 2021. Education and training system post COVID-19: Results from a probability model to measure students’ learning performance. Form@ re-Open Journal per la Formazione in Rete 21: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miksza, Peter, Kelly Parkes, Joshua Russel, and William Bauer. 2022. The well-being of music educators during the pandemic Spring of 2020. Psychology of Music 50: 1152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, Monica, Emanuela Ingusci, Fulvio Signore, Amelia Manuti, Maria Luisa Giancaspro, Vincenzo Russo, Margherita Zito, and Claudio G. Cortese. 2020. Wellbeing costs of technology use during COVID-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability 12: 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My, Sang Tang, Hung Nguyen Tien, Ha Tang My, and Thang Le Quoc. 2022. E-learning Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 21: 160–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nashaat, Nouran, Rasha Abd El Aziz, and Marwa Abdel Azeem. 2021. The mediating role of student satisfaction in the relationship between determinants of online student satisfaction and student commitment. Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education 2021: 404947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, Nedal, Hussam N. Fakhouri, Rula Odeh Alsawalqa, and Faten Hamad. 2022. Music Students’ Perception Towards Music Distance Learning Education During COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Study in Jordan. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies 16.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusseck, Manfred, and Claudia Spahn. 2021. Musical practice in music students during COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 643177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, Burcu, and Emre Ustun. 2020. Evaluation of Students’ Views on the COVID-19 Distance Education Process in Music Departments of Fine Arts Faculties. Asian Journal of Education and Training 6: 556–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, Nur Nadiah Abdul, Norshima Humaidi, Siti Rahayu Abdul Aziz, and Nurul Hidayah Mat Zain. 2022. Moderating effect of technology readiness towards open and distance learning (ODL) technology acceptance during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of University Education 18: 406–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rapanta, Chrysi, Luca Botturi, Peter Goodyear, Lourdes Guàrdia, and Marguerite Koole. 2020. Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science and Education 2: 923–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Hafiz Muhammad Wasif, Yuangiong He, Junaid Khalid, Hafiz Muhammad Usman Khizar, and Suhail Sharif. 2022. The relationship between e-learning and academic performance of students. Journal of Public Affairs 22: e2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, Doris Apriani, Chairul Azmi, and Agung Sunarno. 2020. The Effect of E-Learning toward Student Learning Outcomes. In 1st Unimed International Conference on Sport Science (UnICoSS 2019). Amsterdam: Atlantis Press, pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Roncaglia, Gino. 2020. Cosa succede a settembre? Scuola e didattica a distanza ai tempi del COVID-19. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Rosset, Magdalena, Eva Baumann, and Eckart Altenmüller. 2021. Studying music during the Coronavirus pandemic: Conditions of studying and health-related challenges. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 651393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salayo, Juland, Jann Ernest Fesalbon, Lorena C. Valerio, and Rodrigo A. Litao. 2021. Engagement and Satisfaction of Senior High School Teachers and Students during the Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT). Studies in Humanities and Education 2: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavio, Andrea, Michele Biasutti, and Roberta Antonini Philippe. 2021. Creative pedagogies in the time of pandemic: A case study with conservatory students. Music Education Research 23: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Miwa, Makino Watanabe, Nojiri Shuko, Tsutomu Suzuki, Yuji Nishizaki, Yuichi Tomiki, and Takao Okada. 2022. Effects of COVID-19 on Japanese medical students’ knowledge and attitudes toward e-learning in relation to performance on achievement tests. PLoS ONE 17: e0265356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Ryan D., and Whitney Mayo. 2022. Music education and distance learning during COVID-19: A survey. Arts Education Policy Review 123: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Tae Eun, and Song Yi Lee. 2020. College students’ experience of emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19. Children and Youth Services Review 119: 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulla, Francesco, Antonio Aquino, and Dolores Rollo. 2022a. University Students’ Online Learning During COVID-19: The Role of Grit in Academic Performance. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 825047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulla, Francesco, Benedetta Ragni, Miriana D’Angelo, and Dolores Rollo. 2022b. Teachers’ emotions, technostress, and burnout in distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Paper presented at the Third Workshop on Technology Enhanced Learning Environments for Blended Education, Foggia, Italy, June 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Peter Sin Howe, Yuen Onn Choong, and I-Chi Chen. 2022. The effect of service quality on behavioural intention: The mediating role of student satisfaction and switching barriers in private universities. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 14: 1394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, Ferdinando, Salvatore Zappalà, and Teresa Galanti. 2022. Is a good boss always a plus? LMX, family–work conflict, and remote working satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences 11: 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulaskar, Rucha, and Markku Turunen. 2022. What students want? Experiences, challenges, and engagement during Emergency Remote Learning amidst COVID-19 crisis. Education and Information Technologies 27: 551–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Bin, Yukun Liu, Jing Qian, and Sharon K. Parker. 2021. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology 70: 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, Yalçın, Ece Karşal, and Hakan Bağcı. 2021. Examining the instructors’ perspectives on undergraduate distance learning music instrument education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Pedagogical Research 5: 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, Muhammad, Noor Uzna, Zhou Xiaoyong, Menhas Rashid, and Qingyu Xu. 2022. COVID-19, students satisfaction about e-learning and academic achievement: Mediating analysis of online influencing factors. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 948061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Categories | Numbers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | M | 137 | 42% |

| F | 191 | 58% | |

| Other | 0 | 0% | |

| Total | 328 | 100% | |

| 2. Conservatory | North | 17 | 41% |

| Center | 10 | 24% | |

| South | 14 | 34% | |

| Total | 41 | 100% | |

| 4. Course | Propaedeutic | ||

| Pre-academic | |||

| Academic | |||

| Total | 3 | 100% | |

| 5. Subject | Theoretical | 16.1% | |

| Theoretical–practical | 2.10% | ||

| Stringed instruments | 10% | ||

| Wind instruments—woodwind | 14.3% | ||

| Wind instruments—brass | 9.7% | ||

| Plucked string instruments | 11.6% | ||

| Percussion string instruments | 11.2% | ||

| Percussion instruments | 4% | ||

| Aerophonic instruments | 1.5% | ||

| Sing | 17.3% | ||

| Total | 10 | 100% | |

| 6. Program | Classic | 246 | 75% |

| Jazz | 59 | 18% | |

| Pop | 23 | 7% | |

| Total | 328 | 100% |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Online learning experience (OLE) | 3.45 | 1.84 | 0.42 ** | 0.37 ** |

| 2. Satisfaction with remote education | 3.89 | 1.76 | 0.58 ** | |

| 3. Performance | 2.81 | 0.378 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Label | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Z | p | % Mediation |

| Indirect | a × b | 1.071 | 0.180 | 0.751 | 1.45 | 5.95 | <0.001 | 58.1 |

| Direct | c | 0.771 | 0.276 | 0.267 | 1.36 | 2.79 | 0.005 | 41.9 |

| Total | c + a × b | 1.841 | 0.269 | 1.316 | 2.38 | 6.85 | <0.001 | 100.0 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Z | p | |||

| OLE | → | SOD | a | 1.958 | 0.2487 | 1.456 | 2.468 | 7.87 | <0.001 |

| SOD | → | PERF1 | b | 0.547 | 0.0551 | 0.432 | 0.643 | 9.92 | <0.001 |

| OLE | → | PERF1 | c | 0.771 | 0.2761 | 0.267 | 1.360 | 2.79 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giffi, V.; Fantinelli, S.; Galanti, T. Adapting to Change: Investigating the Influence of Distance Learning on Performance in Italian Conservatories. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120664

Giffi V, Fantinelli S, Galanti T. Adapting to Change: Investigating the Influence of Distance Learning on Performance in Italian Conservatories. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(12):664. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120664

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiffi, Veronica, Stefania Fantinelli, and Teresa Galanti. 2023. "Adapting to Change: Investigating the Influence of Distance Learning on Performance in Italian Conservatories" Social Sciences 12, no. 12: 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120664

APA StyleGiffi, V., Fantinelli, S., & Galanti, T. (2023). Adapting to Change: Investigating the Influence of Distance Learning on Performance in Italian Conservatories. Social Sciences, 12(12), 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120664