Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a public health and widespread problem, and perpetrator programmes are in a unique position to prevent it. Research on the outcomes of perpetrator programmes has advanced in recent years, but still some challenges remain. These challenges include the absence of measures related to survivor safety and wellbeing as well as the impact on the victim. Additionally, other contextual measures, such as motivation to change or taking responsibility, are typically not included in outcome studies. The Impact Outcome Monitoring Toolkit was developed to help overcome these challenges. The participants were 444 men enrolled in a perpetrator programme and their (ex-)partners (n = 272). The results showed that all types of violence were reduced significantly in terms of both frequency and presence, as reported by both the men enrolled in the programme and their (ex-)partners. The impact of violence had been reduced for (ex-)partners, but some still suffered impacts and felt afraid. The results on the impact of violence on children and improved parenting were quite concerning. The Impact Toolkit makes it possible to measure the outcomes of perpetrator programmes in a contextualised manner and has shown promising results, supporting the inclusion of survivor-centric outcome measures.

1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a public health and widespread problem affecting almost one third (27%) of women aged 15–49 years (). In fact, is the most common form of violence against women, affecting around 641 million women and girls globally (). Therefore, IPV is a form of gender-based violence. Preventing IPV has an impact on improving mental health (). In this context, perpetrator programmes are in a unique position to work toward the end of gender-based violence.

Measuring IPV is a difficult endeavour that presents several challenges, both in measuring its prevalence in the general population and in terms of measuring its severity in clinical samples. On the one hand, in terms of measuring IPV prevalence in the general population, traditional crime surveys were not designed to measure domestic violence; thus, they produce underestimates of violence (). New surveys to assess IPV in the general population have been developed to overcome this situation (see, for example, the work conducted in the context of the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW); ). On the other hand, the most widely used tool for measuring IPV in clinical samples is the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2, see ). The CTS2 has been widely criticised for not considering the context of violence (i.e., the impact of violence, reasons/motives for using violence, and initiation), thus resulting in not capturing forms of resistance and coercive control (; ; ; ; ).

IPV research has traditionally focused on physical violence, but when solely focusing on this aspect, it is not easy to identify level of victimisation because both the frequency and type of abuse are crucial to the different experiences of abuse (). In the context of the perpetrator programme evaluation, for example, recidivism has traditionally been considered as a measure of the outcome of programmes. However, even recidivism rates may vary substantially depending on how recidivism is defined and measured. For example, () found that recidivism rates ranged from 7% to 47%, with an average of 26% across all evaluations. Moreover, the average recidivism rates differed depending on whether the victims or male perpetrators assessed it (24% and 34%, respectively); if police records were considered, the recidivism rates changed again, with rates being reduced to approximately one-half of the rate obtained from women’s reports (15%). Along the same lines, () pointed out to a similar average recidivism rate according to court records (22%). Therefore, given the lack of consensus in the scientific community on the assessment of recidivism and its real rate (), it is crucial that IPV research includes not only a wide range of types of abuse but also its frequency, motives, and impact to detect violence under coercive control and to ensure the robust measurement of IPV (; ).

() proposed a twofold strategy, involving carefully assessing the frequency and severity of physical violence one the one hand, and including a measurement of the coercive and controlling context in which the violent acts might be immersed in on the other hand. In this context, the model proposed by Hester and Myhill (see, for example, , ; , ) that integrates the measurement of behaviours (including non-physical forms of coercion such as isolation, intimidation, humiliation, extreme jealousy, etc.) and the impacts that they produce (such as anxiety, extreme fear, diminished space for action, etc.) is crucial to understand the different profiles of perpetration and victimisation (including the nature and severity of abuse and the identification of primary victims and perpetrators) (). On the one hand, it is important to distinguish those experiencing behaviours with low impact and those experiencing more severe impacts from coercive and controlling behaviours. On the other hand, it is crucial to identify those exerting these behaviours and their awareness of the impact of their behaviours. By following this twofold strategy, it will be possible to identify which type of programme works better for different profiles of perpetrators.

As pointed out within the study of (), perpetrator programs can become perpetrator-centric and stray from their original conceptualisation as just one part of an integrated response to IPV. To avoid this, it is crucial to include measures of survivor safety and wellbeing as well as the impact and harm caused to victims in programme evaluations (; ; ). There are two main studies that have explored the impact of perpetrator programmes on women’s and children’s outcomes. One is the Mirabal project, in which six new measures of success were proposed: “respectful communication”, “expanded space for action”, “safety and freedom from violence and abuse for women and children”, “safe, positive, and shared parenting”, “awareness of self and others”, and “safer, healthier childhoods”. The results showed that women had an improved space for action, with large decreases in physical and sexual violence, whereas abuse and harassment changed less. Children’s safety and wellbeing also improved to a small degree (). Previous best practices, such as the Mirabal project, have relied prominently on victims’ accounts. Therefore, different tools were used to assess changes in men in the programme and victim’s safety. Moreover, men in the programme and victims included in the study were not always related to each other (they were not partners or ex-partners). To assess the outcome of perpetrator programmes, it is important to include the (ex-)partners’/victims’ reports, following a dyadic approach. (Ex-)partners are first-hand informers of risks that the programme might arise or mitigate and of the changes that the perpetrator has undergone during the programme. It has been argued that the insights of first-hand informers might be more objective than ones from perpetrators (), as the evidence has shown that men tend to underestimate their perpetration (; ; ). Despite this, the results from the Mirabal project showed that perpetrators’ accounts were more reliable than previous research suggested; therefore, in our study, we included dyads to compare results, prioritising victims’ reports. The second study included partners’ and children’s outcomes for the evaluation of the outcome of the Caring Dads Safer Children (CDSC) programme (). The authors included quantitative measures (some of which were the same for all informants, i.e., fathers in the programme, children, and partners) and qualitative measures (interviews). Their measures analysed changes in parenting skills and the safety and wellbeing of partners and children. The authors found positive results in all of these aspects, but the children’s outcomes presented some mixed results.

Other contextual measures are also crucial when analysing the outcome of perpetrator programmes. Aspects such as motivation to change and/or motives to attend the programme, the demographic characteristics of the men attending the programme (), responsibility/accountability, and self-reported changes () must be considered. In this context, one of the few studies that analysed these concepts found that assuming responsibility for their own reactions was an essential step for men in treatment (). Moreover, men reported changes in their perception about violence, from acknowledging just physical violence to understanding the broader conceptualisation of coercive control (). In their review, () found that no articles have examined the links between men’s accountability and responsibility to the safety and wellbeing of women and children.

The aim of this article is to describe the Impact Outcome Monitoring Toolkit (Impact Toolkit) (), an innovative tool developed in the context of the Impact Project1. The Impact Toolkit measures the outcome of perpetrator programmes in a contextualised manner, including victim safety measures, and following a dyadic approach. This standardised tool is designed to assist in overcoming the limitations in measuring the outcomes of perpetrator programs.

The Impact Toolkit was designed to assess possible changes in perpetrator behaviour and the impact of that behaviour, as well as possible changes in the safety of victims (drawing on the COHSAR approach—).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants in this study included 444 clients enrolled in multiple European programmes for perpetrators of gender-based violence, specifically from the United Kingdom, Italy, Greece, Bosnia, Albania, Serbia, Kosovo, and Bulgaria. Data were also collected from 272 (ex-)partners of the clients. All clients were heterosexual males. The range of ages was wide (see Table 1), with the majority between the ages of 31 and 50 (61.3%). Most of them were full-time workers (62.7%) and low-income level (56.1%). None of them had severe mental disorders or cognitive impairment. Regarding the status of the intimate relationship between the perpetrator and the victim (see Table 1), half of the clients reported being in a relationship, either living together or apart (54.9%). One-third ended the relationship or were in the process of breaking up (37%). In terms of the main hope or wish for the relationship in the future, the majority reported the desire to continue the relationship and live together (60%). In addition, the majority of clients reported having children (78.6%), mainly between 5 and 9 years old (29.3%), but only 3.2% of children of those ages lived with them. Also, a high proportion of children (66.9%) witnessed gender-based violence at some point (33.1% “Never,” 51.3% “Sometimes,” and 15.6% “Often”). Clients were referred to the programme through a large variety of routes. A remarkable proportion (70.8%) attended the perpetrator programme through mandatory referral routes: civil courts (injunction) (19.4%), child protection (11.9%), restorative justice (11.5%), civil courts (custody/access) (8.8%), criminal courts (8.6%), police (5.4%), or probation (5.2%). Also, there were a proportion of clients that were pressured to attend by their partner/ex-partner (9.9%) and by friends or family (6.3%). Last but not least, some clients were referred via the following channels: publicity (poster or internet advertisements) (10.8%), helpline (5.9%), relationship counselling service (3.8%), addiction service (3.6%), counselling/mental health service (3.4%), or health services (2%). None of them were referred to the perpetrator programme by a religious place.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of male perpetrators.

The reasons for joining the programme were also diverse. Despite the majority referring to both external and internal reasons, half of the clients declared external reasons, such as being referred as part of criminal court (25%) or family court (16.9%) sentences or being referred by child protection services (8.3%). In addition, a high variety of internal reasons was obtained: to improve their couple relationship (32.9%), to stop using violence (26.6%) and/or abusive behaviour (23.6%), wanting their (ex-)partner to feel safe around them (22.3%), wanting their (ex-)partner (25%) and/or child(ren) (16.7%) to not be afraid of them, and being a better father to their children (21.6%). Also, a small number of men indicated the fear of being left by their partner (18.2%) or the fear of going back to prison again as reasons for joining the programme (6.3%).

2.2. Measures

The Impact Outcome Monitoring Toolkit questionnaire of the “European Network for the Work with Perpetrators of Domestic Violence (WWP EN)” was used in this study. This instrument comprises ten versions of the questionnaire, slightly adapted in relation to the treatment phase (five versions: T0—before starting the programme, T1—at the beginning of the programme, T2—in the middle, T3—at the end of the programme, and T4—follow-up) and in relation to the respondent (two versions: client and (ex-)partner). Due to the low response rates obtained in the follow-up measurement (T4), we focused on the responses to the questionnaire for perpetrators and (ex-)partners at Times 1, 2, and 3. The scales included were as follows: violent behaviour (emotional, physical, and sexual), impact of the violence on the victim and child(ren), victim’s safety, perpetrator’s self-responsibility for violence, and perpetrator’s positive changes. All the items of violent behaviour, impacts, police calls, (ex-)partner’s fear, and positive changes scales were equivalent across the clients’ and (ex-)partners’ questionnaires. Anxious and depressed feelings were reported by (ex-)partners, and the self-responsibility for violence was reported by clients. The first scale (violent behaviour) contains 29 items divided into three sub-scales regarding three types of IPV: emotional (13), physical (14), and sexual behaviour (8). These sub-scales assessed the frequency of each violent behaviour through a 3-point Likert scale (“Never”, “Sometimes”, “Often”). The second scale (impact of violence on victim) comprises 16 items about physical and emotional impacts on the (ex-)partner, measured through a dichotomic scale (“Yes”, “No). The third scale (impact of violence on children) includes 11 items about the situation and angry feelings toward the parents of the child(ren), also measured with a dichotomic scale. The fourth scale (victim’s safety) includes three frequency sub-scales: police calls (“Not at all”, “Once”, “2–5 times”, “6–10 times”, “More than 10 times”), as well as (ex-)partner’s anxious and depressed feeling (“Never”, “Not often”, “Sometimes”, “Often”, “Always”). The fifth scale (perpetrator’s self-responsibility for violence) is composed of 17 items about the internal or external attribution (locus of control) of the reasons for violence. Finally, the sixth scale (Perpetrator’s positive changes) includes 23 items about changes made by the client, such as stopping using violence or improving their parenting skills.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The data were obtained by intentional sampling () in the context of the Impact Project2. Responses from the clients and (ex-)partners were collected at the beginning of each round of the programme. The procedure used to collect the answers was different for each group. On the one hand, clients responded to the questionnaire on-site and on paper. They did it alone, but a facilitator was present in the room to assist with any questions or clarifications they might have. On the other hand, partners and ex-partners were contacted at the beginning of the programme to inform them about the content and methods of the programme, to provide support services in case they needed them, and to learn about their experience of violence and their assessment of the outcome of the programme. Thus, (ex-)partners responded to the questionnaire because of their involvement in the process. Responses were collected either over the phone or face-to-face depending on the availability of each case.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program, v. 29.0. Responses from clients were paired with the data from their (ex-)partners. Within-group comparison tests were carried out to analyse the outcome of the programme, examining the time differences at T1, T2, and T3. Between-group comparison tests were performed to analyse possible differences between clients and (ex-)partners perceptions. Due to the response rate obtained (see Table 2) and as a result of time and group pairings, within-groups analyses included a sub-sample of 133 males and 71 of their (ex-)partners, which were adjusted for between-group comparisons (n = 71). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to ascertain the normality in the sample distribution. Because the data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05), the Friedman test was performed to assess a within-group analysis across the programme time points. The Bonferroni post hoc test was also performed to analyse paired-time comparisons. Also, the corrected Cohen effect sizes () were calculated by subtracting the mean difference between the T1 and T3 measures. The Mann–Whitney U test was carried out to analyse the between-group comparison. Finally, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was computed to analyse the possible linear relationship between the types of violent behaviours reported by clients and (ex-)partners.

Table 2.

Frequency and rate of responses at each time point.

2.4. Ethical and Safety Measures

All the information was gathered through community-based services to ensure safety procedures (). This was a crucial measure to ensure victim safety because all of the organisations involved in this project had procedures in place in case of escalation of violence or if the safety of the victim was threatened. Moreover, the researchers involved in this research did not have direct access to either the victims or the perpetrators. In this sense, the team of researchers involved in this study received anonymised data through alphanumeric codes assigned by each organisation. All the organisations that implemented the Impact Outcome Monitoring Toolkit in their perpetrator programs were responsible for contacting the victims (ensuring their safety) as well as for maintaining the psychoethical guarantees of confidentiality, anonymity, and privacy. In order to guarantee this, all the involved staff of these organisations (coordinators, facilitators, and administrators) were trained before gathering data using the Impact Outcome Monitoring Toolkit questionnaire. This training was delivered by the professional responsible of the Impact Project in WWP EN. The training focused on understanding the structure and content of the tool and how to implement it in a safe way. Recommendations for contacting the victim were discussed in light of the quality standards for victim-safety-oriented perpetrator programmes developed by WWP EN.

3. Results

For each type of outcome measured, the within-group comparison was used to determine the effectiveness of the programmes. Gender-based violence, impact on (ex-)partners and children, police calls, and (ex-)partner fear variables were assessed according to information reported by both clients and (ex-)partners. Feelings of anxiety and depression were reported only by the (ex-)partner. Clients’ self-responsibility for violence was also assessed longitudinally. Moreover, a between-group comparison was used to assess possible differences in the perception of clients and their (ex-)partners at each time point on the following variables: violent behaviour and its impact, the victim’s safety, and the positive changes made by the perpetrator.

3.1. Violent Behaviour

3.1.1. Longitudinal Programme Outcomes

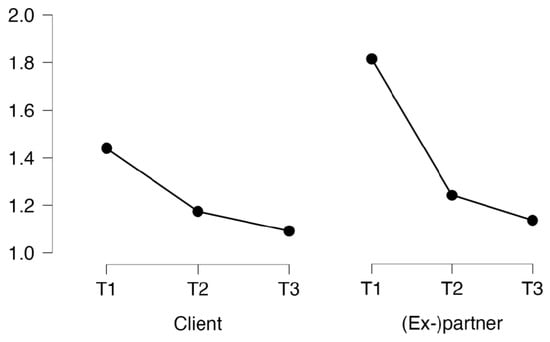

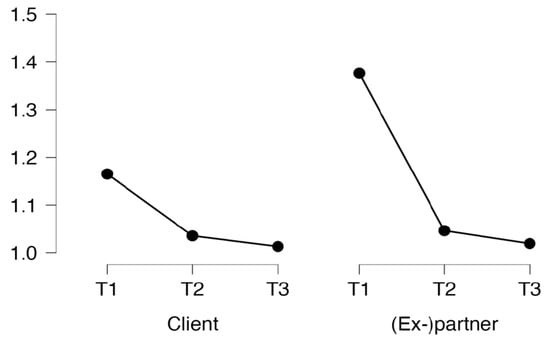

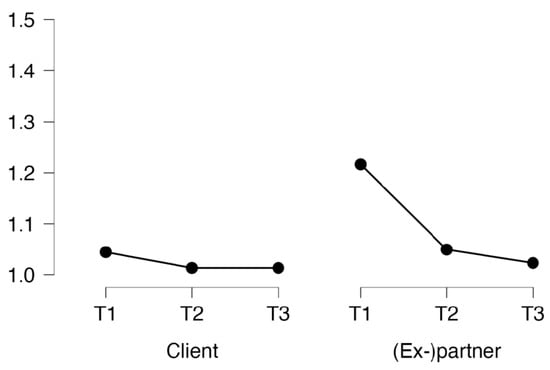

The obtained outcomes (see Table 3) showed that all types of violence (emotional, physical, and sexual) decreased significantly (p < 0.001) along the three measures, according to both clients and (ex-)partners. The effect size (Cohen’s d) obtained was high for emotional and physical violence. For sexual violence, a medium effect size was observed for the client data and a high effect size for the (ex-)partner data. As can be seen in Table 3, it is noteworthy that the decrease in emotional violence was very pronounced according to (ex-)partners, with a global frequency decrease from “Sometimes” at the beginning of the programme (T1) to “Never” at the end (T3). Conover’s post hoc tests were carried out to analyse paired-time differences. On the one hand, the results obtained demonstrated that emotional violence (see Figure 1) decreased significatively at each paired-time group (T1–T2, T2–T3, T1–T3) according to both clients and (ex-)partners (p < 0.001). On the other hand, physical violence (see Figure 2) decreased significantly in the T1–T2 and T1–T3 paired groups according to both clients and (ex-)partners (p < 0.001). Finally, a significant decrease in sexual violence (p < 0.001) was also obtained in the T1–T2 and T1–T3 paired groups, although the decrease was greater for (ex-)partners due to the low levels reported by clients at the beginning of the programme (see Figure 3). As seen, both groups perceived the decrease in emotional and physical violence more pronouncedly between the beginning (T1) and the middle of the programme (T2), while men’s perceptions of sexual violence was more linear (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Within-group comparisons for violence.

Figure 1.

Emotional behaviour decrease reported by clients and (ex-)partners.

Figure 2.

Physical behaviour decrease reported by clients and (ex-)partners.

Figure 3.

Sexual behaviour decrease reported by clients and (ex-)partners.

3.1.2. Between-Group Comparisons: Perceptions of Clients and (Ex-)partners

At the beginning of the programme (T1), the Mann–Whitney U test showed a significant difference in all types of violence (emotional, physical, and sexual) between groups (p < 0.001). (Ex-)partners reported a higher frequency of violence than clients in this measurement. In the middle of the programme (T2), a significant difference was only obtained in terms of sexual violence (U = 5337.0; p < 0.001), also with higher rates reported by (ex-)partners. At the end (T3), perceptions of emotional violence differed significantly between the groups. The relationship between the frequency of violence reported by clients and (ex-)partners was also assessed. Spearman’s correlation (see Table 4) demonstrated a significant correlation between emotional, physical, and sexual violence according to both clients and (ex-)partners. However, violence reported by clients and (ex-)partners was not significantly related, which is consistent with the results obtained in the Mann–Whitney U test and reinforces the found differences.

Table 4.

Spearman’s correlations among the frequency of violent behaviour of both groups.

3.2. Impact of Violence on the Victim and Child(ren)

3.2.1. Longitudinal Programme Outcomes

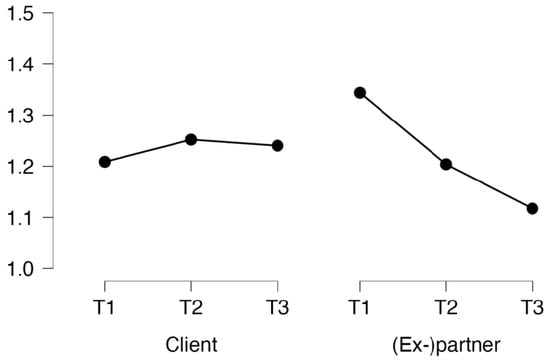

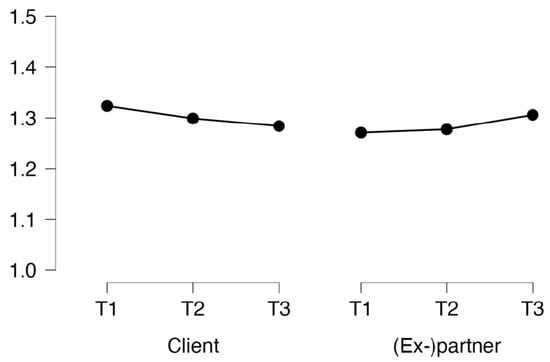

According to the client data, the impacts on the (ex-)partner and child(ren) were sustained over time (p > 0.05). However, based on the (ex-)partner data, the impact on themselves was significantly reduced (p < 0.001) with a high effect size (see Table 5). Specifically, Conover’s post hoc test showed a significant decrease (p < 0.001) at each paired-time group (T1–T2, T2–T3, and T1–T3). In addition, the impact of the violence on children increased significantly according to (ex-)partners, although with a low effect size. Specifically, Conover’s post hoc test showed that the increase was significant (T-Stat = 2.739; p = 0.008) from the beginning to the end of the programme (T1–T3). Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the difference in the impacts perceived by clients and (ex-)partners. In this sense, the clients’ perception of the impact increased slightly, but (ex-)partners reported a progressive decrease in the impacts (see Figure 4)3. Also, although the differences between the time measures were minimal, clients and partners had diametrically opposed views toward the impact on children (see Figure 5).

Table 5.

Within-group comparisons for violence and its impacts.

Figure 4.

Impact on (ex-)partner evolution reported by clients and (ex-)partners.

Figure 5.

Impact on child(ren) evolution reported by clients and (ex-)partners.

3.2.2. Between-Group Comparisons: Perceptions of Clients and (Ex-)partners

Regarding the effects of violence, the perception of the impact on the (ex-)partner was significantly different at T1 (U = 6578.0; p < 0.001) and T3 (U = 2538.0; p < 0.001). Interestingly, while (ex-)partners reported a higher impact at T1, clients had a higher mean than (ex-)partners at the end of the programme (T3). This result denotes a greater awareness of the clients of the impact of their violence on their (ex-)partner. On the other hand, the impact on children was significantly different at T1 (U = 1795.0; p = 0.008), with clients reporting a higher impact. At the beginning of the programme, men and their (ex-)partners differed in the following impacts, which were relevant according the to the (ex-)partners but not according to the men: “felt unable to cope”, “felt worthless or lost confidence”, “felt isolated/stopped going out”, and “feared for life”. At the end of the programme, all of these impacts were reduced for the (ex-)partners. Therefore, the most commonly reported impacts by both at the end of the programme were the same (“lost respect for your partner”, “felt sadness”, and “felt angry/shocked”). The only impact that was relevant for some (ex-)partners but not for the men in the programme referred to “being careful what you say or do”4 (see Appendix A, Table A1).

3.3. Victim Safety and Wellbeing

3.3.1. Longitudinal Programme Outcomes

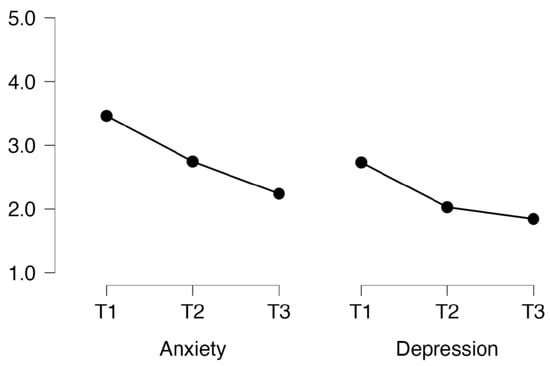

The within-group comparisons (see Table 6) showed that the frequency of calls to the police and (ex-)partners’ fear decreased significantly (p < 0.001), according to both the clients and (ex-)partners, with a high effect size. More precisely, Conover’s test demonstrated a significant decrease in police calls between T1–T2 and T1–T3, according to both groups (p < 0.001). Also, (ex-)partners’ fear decreased significantly at each paired-time group (T1–T2, T2–T3, and T1–T3) according to both clients and (ex-)partners (p < 0.05). Both variables followed similar patterns of decline in clients and (ex-)partners. According to (ex-)partners, their anxious and depressed feelings decreased significantly over time (p < 0.001) with a high effect size. Interestingly, Conover’s test showed that the decrease in anxiety was significant at each time measure (p < 0.01), while depression did not decrease significantly between the middle and the end of the programme. This difference indicates an abrupt decrease in depressive feelings in the early phases of the programme, while anxious feelings decreased more gradually (see Figure 6).

Table 6.

Within-group comparisons for (ex-)partner’s safety and wellbeing.

Figure 6.

Anxiety and depression feeling evolution reported by (ex-)partners.

3.3.2. Between-Group Comparisons: Perceptions of Clients and (Ex-)partners

In terms of victim safety, similar perceptions were obtained between groups in terms of the frequency of calls to the police (p > 0.05). However, the results of (ex-)partners’ fear were statistically different in the three measurements (p < 0.001). Specifically, (ex-)partners reported greater fear than that perceived by the clients.

3.4. Perpetrator Self-Responsibility for Violence

Longitudinal Programme Outcomes

As seen in Table 7, the clients’ assumptions of the responsibility of their perpetrated violence remained stable over time (p > 0.05). Therefore, neither a significant decrease nor an increase in the internal or external locus of control was obtained. In this sense, the proportion of men who reported using violence to feel in control remained stable between T1 (24.1%) and T3 (18%). However, coercive motives (“To make her do something I want her to do”) increased slightly from T1 (16.5%) to T3 (25.6%). Similarly, at T1, only 34.6% of clients reported being jealous and possessive as a reason for their violence in contrast to 45.9% obtained at T3. These results could indicate an increase in the internal locus of control of the violence. Nevertheless, other external motives for violence, such as drug or alcohol use, remained stable on the pre and post measures (21.8%; 19.5%).

Table 7.

Within-group comparisons for client’s responsibility variables.

3.5. Perpetrator Changes

Between-Group Comparisons: Perceptions of Clients and (Ex-)partners

Regarding the changes reported by clients and (ex-)partners at the end of the programme (T3), a significant difference was obtained (U = 5795.0; p = 0.007). It is important to note that clients reported more changes than (ex-)partners. In this sense, 66.2% of clients and 49.3% of (ex-)partners stated that the client had stopped using violence. Also, a greater proportion of perpetrators (97%) than victims (87.3%) reported that the (ex-)partners were no longer afraid of the clients. The difference in the perception of the children’s fear of the perpetrator was more marked. Whereas almost half of the men (39.8%) reported that their child was no longer afraid of them, only 16.9% of the women felt this to be the case. However, similar proportions were obtained in terms of the parenting improvement of the client, as was reported by 40.6% of clients and 38% of (ex-)partners.

4. Discussion

In this article, we showed a procedure and a tool to evaluate the outcome of perpetrator programmes for IPV in a contextualised way. By including several types of violence, the impact of violence and other contextual aspects and by including men in the programme and (ex-)partners as informants in our study, we found several interesting results.

First, the types of violence were significantly reduced in terms of both frequency and presence, as reported by both the men enrolled in the programme and their (ex-)partners. This reduction was particularly noticeable during the first half of the programme. This is in line with previous results from the few studies that have included information from men in the programme and their (ex-)partners (; ). Moreover, according to our results, the views about violence were very different from each other, especially at the beginning of the programme. At the end of the programme, the views were more similar, but the (ex-)partners still identified a higher frequency of emotionally violent behaviour than the men. This finding aligns with previous studies that suggested that emotional abuse, while reduced, remained present after perpetrator programs, according to (ex-)partners (; ). Finally, it was possible to identify that all types of violence measured in this study were related to one another, so they were not isolated.

Second, the impact of violence measured according to the men in the programme and their (ex-)partners was reduced significantly according to the (ex-)partners. At the same time, men in programme experienced a slight increase in the awareness of the impact of their violence toward their (ex-)partners. It is important than nearly one-third of the (ex-)partners still thought they had to be careful about what they said and did and still felt sad. This reflects how the coercive control might still be present even if the violence has been significantly reduced. Similarly, the results from the Mirabal project showed that women felt they gained space for action; however, this achievement was mostly attributed to their efforts and not to the men’s changes, and some women still remained cautious and felt afraid of doing/saying certain things (). This study found that the impact of violence on children was quite concerning, particularly from the perspective of (ex-)partners who detected more impacts on the children after the perpetrator programme. Many children were still reported to be afraid of the men, especially according to (ex-)partners. Furthermore, even if the parenting seemed to improve for a few men, the majority of the men did not improve their parenting (according to the men themselves and their (ex-)partners). Previous research has rarely considered children when evaluating the outcome of perpetrator programmes. As mentioned in the introduction, () and () have analysed children’s wellbeing as an outcome measure of perpetrator programmes by gathering information from the children directly. The second study found that children and partners described positive changes in the fathers’ behaviour; however, some fathers continued to pose a risk as their behaviours had not changed or had only changed partially. The previous study found slightly better outcomes for children than our study, which might suggest that more focus on parenting should be included in perpetrator programmes. The Mirabal project found discrepant results; in terms of parenting, some improvement was detected, although women were still worried about leaving the child with the man alone. Better results were found in terms of the men’s awareness of the impact of their behaviour on children (with 16% of women stating that the man did not understand this impact). However, in terms of safety and impact, women reported many impacts on children. More than half of the women stated that children were nervous, anxious, afraid of IPV, or worried about the mother’s safety. This was the measure with less change. Therefore, more focus on children should be included in programmes for perpetrators of IPV, especially considering that survivors are more concerned about the effects of violence on their children than about the incidents of physical violence ().

Third, safety has traditionally been measured with indicators such as programme completion and re-assault statistics as the main measures (; ). Similar to the Mirabal project (), our study focused on survivor wellbeing and feelings of safety. According to our results, while survivors’ feelings of safety increased over the course of the program, (ex-)partners continued to experience fear throughout the programme, even at the end. Again, this result suggests that coercive control may still be present even when physical violence is reduced. A qualitative study analysing victims’ fear found that memories of past abuse, as well as the realisation that their (ex-)partner would probably not become the partner they wanted him to be, resulted in different levels of fear (). Moreover, previous studies have shown that survivors did not fully believe the changes made by the men and thought that it was a way for them to show improvement to the facilitators (). Similarly, in our study, we observed that the men in the programme reported higher levels of change than their (ex-)partners, presenting a more positive view of their own changes.

Fourth, our results indicate an increase in the internal locus of control of men in the programme and more awareness of the reasons for violence related to coercive control, indicating an expanded understanding of violence (; ).

Limitations and Proposals for Future Research

This study has some limitations, with the loss of participants over time being an important one. This research was based on the data available for each time point, with fewer (ex-)partner responses in each time point and few responses at a follow-up. For this reason, to compare results within couples, we had to dismiss the information from men that did not have answers from (ex-)partners. Moreover, we could not analyse the data from the follow-up surveys. As the objective of this paper was to showcase the new methodology for measuring the outcome of perpetrator programmes in a contextualised manner, further analyses were out of the scope of this article. In future research, it is recommended to analyse data from all men and compare men that have (ex-)partner information and those that do not in order to establish different profiles. It is important to mention that this study focused on heterosexual relationships and, hence, the results should be considered in caution. Future research should extend the scope and include participants form the LGBTQ++ communities. Another limitation is that the study did not consider the different profiles of the men in the programme and of the victims when performing the analysis. Future research should focus on thoroughly analysing the demographic data and integrating this information with the programme outcome. Also, in addition to sociodemographic information on perpetrators, it would be essential to take into account the importance of other environmental variables related to violence, highlighting the importance of the ecological model in order to understand violence in a more comprehensive way. Finally, in future research, it would be important to further analyse the outcomes considering the programme characteristics, making it possible to detect different types of programmes that work better for specific perpetrator profiles.

5. Conclusions

The procedure presented in this article for measuring the outcome of perpetrator programmes in a contextualised manner has shown promising results in detecting changes in violence and the impact of this violence, making it possible to identify different profiles of perpetrators and victims in future research. Moreover, by including several measures of success, it indicates the importance of measuring victim safety and of including a thorough assessment of children’s’ wellbeing. Including information from the (ex-)partners has proven to be crucial when analysing perpetrator programme outcomes. Therefore, when conducting this type of research, a linkage with community-based services is essential for a safe data collection process.

Longitudinal measures of outcome have made it possible to distinguish when change happens and how the process of change occurs during perpetrator programmes. This information can inform practitioners in making decisions about the programme characteristics. Finally, the Impact Outcome Monitoring Toolkit gathers not only thorough information about demographic data of perpetrators and victims but also information about the programme characteristics, making it possible to analyse the outcome of perpetrator programmes according to the perpetrator and victim profiles and programme characteristics.

All in all, this study is in line with previous studies in supporting evidence for including survivor-centric outcome measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.V., A.P. and M.H.; methodology, B.V. and J.G.M.; validation, B.V.; formal analysis, J.G.M.; investigation, B.V. and J.G.M.; data curation, B.V. and J.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.V. and J.G.M.; writing—review and editing, B.V. and J.G.M.; supervision, A.P. and M.H.; project administration, B.V.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Comission under the “Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme 2021–2027” grant number 101104750.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the European Network for the Work With Perpetrators (WWP EN) (protocol code 24022016 and 25-02-2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1 with a Description of the Prevalence of Impacts Reported by Clients and (Ex-)partners at T1 (Pre) and T3 (Post).

Table A1.

Prevalence of impacts reported by clients and (ex-)partners at T1 (pre) and T3 (post).

Table A1.

Prevalence of impacts reported by clients and (ex-)partners at T1 (pre) and T3 (post).

| Pre | Post | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client | (Ex-)partner | Client | (Ex-)partner | |||||

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | |

| (Partner) felt sadness *** | 72 | 54.1 | 58 | 81.7 | 76 | 57.1 | 20 | 28.2 |

| (Partner) felt angry/shocked ** | 61 | 45.9 | 36 | 50.7 | 61 | 45.9 | 14 | 19.7 |

| (Partner) lost respect for (client) ** | 53 | 39.8 | 30 | 42.3 | 58 | 43.6 | 12 | 16.9 |

| (Partner) stopped trusting (client) ** | 51 | 38.3 | 34 | 47.9 | 59 | 44.4 | 9 | 12.7 |

| Made (partner) feel afraid of you ** | 39 | 29.3 | 27 | 38.0 | 43 | 32.3 | 8 | 11.3 |

| Made (partner) want to leave (client) ** | 37 | 27.8 | 21 | 29.6 | 33 | 24.8 | 8 | 11.3 |

| (Partner suffered) injuries such as bruises/scratches/minor cuts *** | 32 | 24.1 | 33 | 46.5 | 36 | 27.1 | 4 | 5.6 |

| (Partner) felt anxious/panic/lost concentration * | 28 | 21.1 | 25 | 35.2 | 33 | 24.8 | 11 | 15.5 |

| (Partner suffered) depression/sleeping problems *** | 22 | 16.5 | 28 | 39.4 | 30 | 22.6 | 5 | 7.0 |

| (Partner) felt worthless or lost confidence * | 19 | 14.3 | 22 | 31.0 | 26 | 19.5 | 8 | 11.3 |

| (Partner) felt isolated/stopped going out *** | 17 | 12.8 | 22 | 31.0 | 24 | 18.0 | 5 | 7.0 |

| (Partner) feared for their life * | 16 | 12.0 | 27 | 38.0 | 11 | 8.3 | 2 | 2.8 |

| (Partner) had to be careful of what they said/did * | 15 | 11.3 | 31 | 43.7 | 34 | 25.6 | 19 | 26.8 |

| (Partner) felt unable to cope * | 14 | 10.5 | 28 | 39.4 | 26 | 19.5 | 7 | 9.9 |

| (Partner suffered) injuries needing help from doctor/hospital ** | 12 | 9.0 | 14 | 19.7 | 8 | 6.0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Made (partner) worried (client) might leave | 6 | 4.5 | 8 | 11.3 | 9 | 6.8 | 2 | 2.8 |

| Made (partner) defend self/children/pets * | 5 | 3.8 | 16 | 22.5 | 10 | 7.5 | 5 | 7.5 |

| (Partner) self-harmed/felt suicidal | 4 | 3.0 | 2 | 2.8 | 3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

Note. Items are ordered according to the prevalence of impact reported by clients at T1 (pre). Between-group comparisons are displayed for both measurements and marked as follows: * p < 0.05 (pre-measurement); ** p < 0.05 (post-measurement); *** p < 0.05 (both measurements).

Notes

| 1 | Project “IMPACT: Evaluation of European Perpetrator Programmes” funded by the European Commission (Daphne III Programme) 2013–2014. |

| 2 | See: https://www.work-with-perpetrators.eu/impact (accessed on 20 September 2023). |

| 3 | This difference is attributable to the fact that for the men in the programme, the question about the impact referred to the impact that the (ex-)partner might have suffered at any time, with the objective of detecting if there was more awareness of the impact of his behaviour through the programme. Oppositely, for the (ex-)partner, the question was time-sensitive and it asked about the impact she had suffered since the last time she answered the questionnaire. |

| 4 | Although this impact was marked by approximately 20% of the sample of men and (ex-)partners, this was the most relevant impact for the (ex-)partners and for the men it was not. Men in the programme increased their awareness of this impact (from 12% to 26% men that were aware of this impact), but not significantly. |

References

- Ackerman, Jeffrey. 2016. Over-reporting intimate partner violence in Australian survey research. British Journal of Criminology 56: 646–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldarondo, Etiony. 2010. Understanding the Contribution of Common Interventions with Men who Batter to the Reduction of Re-assaults. Juvenile and Family Court Journal 61: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, Annah. 2017. Ethics, Methods, and Measures in Intimate Partner Violence Research: The Current State of the Field. Violence against Women 23: 1382–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butters, Robert P., Brian A. Droubay, Jessica L. Seawright, Derrik R. Tollefson, Brad Lundahl, and Lauren Whitaker. 2021. Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrator Treatment: Tailoring Interventions to Individual Needs. Clinical Social Work Journal 49: 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1992. Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112: 155–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeKeseredy, Walter, and Martin Schwartz. 1998. Measuring the Extent of Woman abuse in Intimate Heterosexual Relationships: A Critique of the Conflict Tactics Scales. Harrisburg: VAWnet. [Google Scholar]

- Dobash, Russell P., R. Emerson Dobash, Kate Cavanagh, and Ruth Lewis. 1999. A research evaluation of British programmes for violent men. Journal of Social Policy 28: 205–33. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-social-policy/article/research-evaluation-of-british-programmes-for-violent-men/E921118F14303B91EBD22EDC9495D638 (accessed on 22 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gondolf, Edward. W. 1999. A comparison of four batterer intervention systems: Do court referral, program length, and services matter? Journal of Interpersonal Violence 14: 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondolf, Edward W., and Angie K. Beeman. 2003. Women’s Accounts of Domestic Violence Versus Tactics-Based Outcome Categories. Violence Against Women 9: 278–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberger, L. Kevin, Sadie Larsen, and Jacquelyn Campbell. 2016. Methodological Contributions to the Gender Symmetry Debate and its Resolution. Journal of Family Violence 31: 989–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, Sherry. 2016. Self-report measures that do not produce gender parity in intimate partner violence: A multi-study investigation. Psychology of Violence 6: 323–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, Marianne, Catherine Donovan, and Eldin Fahmy. 2010. Feminist epistemology and the politics of method: Surveying same sex domestic violence. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 13: 251–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, Marianne, Sarah-Jane Walker, and Andy Myhill. 2023. The Measurement of Domestic Abuse—Redeveloping the Crime Survey for England and Wales. Journal of Family Violence 38: 1079–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibberts, Marry, R. Burke Johnson, and Kenneth Hudson. 2012. Common survey sampling techniques. In Handbook of Survey Methodology for the Social Sciences. New York: Springer, pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Liz, and Nicole Westmarland. 2015. Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programmes: Steps Towards Change. Project Mirabal Final Report. Available online: http://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/id/eprint/1458 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Lauch, K. McRee, Kathleen J. Hart, and Scott Bresler. 2017. Predictors of treatment completion and recidivism among intimate partner violence offenders. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 26: 543–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, Nicola, Matt Barnard, and Julie Taylor. 2017. Caring Dads Safer Children: Families’ Perspectives on an Intervention for Maltreating Fathers. Psychology of Violence 7: 406–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinn, Tony, Brian Taylor, and Mary McColgan. 2021. A Qualitative Study of the Perspectives of Domestic Violence Survivors on Behavior Change Programs with Perpetrators. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 9364–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhill, Andy. 2015. Measuring coercive control: What can we learn from national population surveys? Violence against Women 21: 355–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myhill, Andy. 2017. Measuring domestic violence: Context is everything. Journal of Gender-Based Violence 1: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Amanda, Heather Morris, Anastasia Panayiotidis, Victoria Cooke, and Helen Skouteris. 2021. Rapid review of Men’s Behaviour Change Programs. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 22: 1068–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto e Silva, Teresa, Olga Cunha, and Sónia Caridade. 2023. Motivational interview techniques and the effectiveness of intervention programs with perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24: 2691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, Chiara. 2019. The Social Dimensions of Intimate Partner Violence: A Qualitative Study with Male Perpetrators. Sexuality & Culture 24: 749–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skafida, Valeria, Gene Feder, and Christine Barter. 2023. Asking the Right Questions? A Critical Overview of Longitudinal Survey Data on IntimatePartner Violence and Abuse Among Adults and Young People in the UK. Journal of Family Violence 38: 1095–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, Murray A., Sherry L. Hamby, Sue Boney-McCoy, and David B. Sugarman. 1996. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues 17: 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, Áine, Tracey McDonagh, Twylla Cunningham, Cherie Armour, and Maj Hansen. 2021. The effectiveness of interventions to prevent recidivism in perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 84: 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vall, Berta, Anna Sala-Bubaré, Marianne Hester, and Alessandra Pauncz. 2021. Evaluating the impact of intimate partner violence: A comparison of men in treatment and their (ex-) partners accounts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021. Violence Against Women. Geneva: WHO, March 9, Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- World Health Organization. 2022. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Improves Mental Health. Geneva: WHO, October 6, Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/06-10-2022-preventing-intimate-partner-violence-improves-mental-health#:~:text=Intimate%20partner%20violence%20is%20the,and%20other%20mental%20health%20problems (accessed on 19 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).