Abstract

By approaching border security as a form of social interaction, the aim of this research is to provide a more thorough consideration of the how in the everyday communicative practices of police officers and civilians who participate in crime control at borders. Employing a corpus of 272 videos of police checks carried out by the Spanish Guardia Civil at La Jonquera–Le Perthus (the Spain–France border area), conversation analysis (CA) is introduced and applied as a novel perspective in the field of border security studies. From this approach, this article scrutinizes how meaningful actions emerge, and their relevance to the development of the encounter. The analysis highlights how certain actions can be consequential for police checks, such as initiating and modifying turns in conversation to overcome problematic situations that arise, for example, from the (non) ownership of the stopped vehicle, or the (lack of) reason for stopping it, which interfere with the police agenda in the management of border security (i.e., the resolution of suspicion). Consequently, this article sheds light on the role of CA in promoting analyses of micro-level border practices, allowing for the detailed examination of how border encounters are locally managed.

1. Introduction

Since the Schengen Agreement came into effect in 1995, the 26 current member states of its area1, which are integrated and regulated by the Schengen acquis, have abolished border controls at internal borders. However, the police authorities of the member states can still exercise their powers at internal borders and within border areas in the form of spot-checks to combat cross-border crime2. In this context, the police may stop vehicles or let civilians go. As these police checks are not systematic border controls, the decision to stop civilians or not comes down to police discretion (see Figure 1). When police officers have not identified anything that warrants grounds for suspicion, they let civilians go. However, in accordance with the fieldwork and data gathered for this project, as well as the comments of the officers who participate in police checks in the La Jonquera–Le Perthus border area, civilians can be stopped on the basis of random criteria (to counter criminals’ strategies) or due to inferences of suspicion (e.g., driving alone) (for further reference, see Mora-Rodriguez 2022).

Figure 1.

A police officer signals a driver to stop the vehicle by holding up a hand (authors’ data collection).

Nonetheless, there is a certain invisibility surrounding these police checks in internal border areas (Barbero 2018). For this reason, an analysis has been performed of these types of police checks that are not supposedly border control. The main objective is to contribute to a better understanding of everyday practices of the actors, namely police officers (state agents) and civilians (non-state agents), who participate in actual police checks in internal Schengen border areas. Despite recent interest in analysing border security as a practice, that is, how border security actors behave and how they give meaning to their actions (Côté-Boucher et al. 2014), it is still unclear how police officers and civilians respond to one another socially in interaction, particularly in terms of how they sequentially design and manage their actions as well as the impact these have on border security enforcement. To answer these questions, social interactions occurring during police checks were analysed. For this purpose, conversation analysis is introduced to the field of cross-border crime, the aim being to provide a more thorough consideration of the how of border security.

The practices identified and analysed in this article are those that are used by police officers and civilians to shape and condition the progressivity of the encounter. These practices are analysed and divided into two sections. The first section (Section 3.1) refers to how and in what specific circumstances police officers warrant stopping people in a border area where border controls have supposedly been abolished, and hence addresses the debate on how law enforcement (specifically the Guardia Civil) justifies its control over the movement of people by framing border security discourse in a specific manner (see Bigo 2000). The second section of the analysis (Section 3.2) refers to how civilians act during these interactions with the intention of conditioning the PO’s resolution of the suspicion towards them from the moment they are asked to stop. CA allows us to observe how not only border jurisdiction but also suspicion shape actions in these encounters, generating a sequential organization that depends on discretionary decisions taken by participants on a moment-by-moment basis (i.e., border security as a practice). In short, both sections of the analysis identify and examine practices and actions in interaction that are oriented towards the resolution of a problem (i.e., the reason for stopping people in a “borderless area”, and the resolution of suspicion).

1.1. La Jonquera–Le Perthus Border Area

This article focuses on the La Jonquera–Le Perthus border area between France and Spain as a case study, as both countries are EU and Schengen members. Specifically, for this article the analysis is of police checks involving crime control (i.e., cross-border crime) performed by the Guardia Civil (the Spanish police corps of a military nature). The Spanish–French border runs for over 650 kilometres along the natural frontier that follows the Pyrenees from the Cantabrian Sea to the Mediterranean. Established by the Pyrenees Treaty (1659), it is one of the oldest borders in Europe, and was delimited by the Bayona Treaties (1856–1868). It has been historically characterized by the transition of populations, mostly from Spain to France as a result of the major intolerance and persecution in Spain until the 19th century of those who disagreed with the Spanish monarchy (Berdah 2009). During the 20th century, under the Franco dictatorship, Republican refugees also crossed the border. Currently, it is predominantly a route for migrants and asylum seekers who want to reach France or other European countries. Nowadays, Spain is considered a “hot spot” for the risk of terrorism due to recent attacks such as the those in Barcelona and Cambrils in 2017. This makes the securitisation of the Spanish borders more a matter of security than immigration control (Barbero 2018).

The La Jonquera–Le Perthus border area has been a primary focus since the 1950s, when the Franco regime sought to improve economic relations with Western Europe. This led to a more open Spanish–French border and turned La Jonquera into a centre for customs duties (Markuszewska et al. 2016). Today, La Jonquera is a small village, 5km from the Spanish–French border. It can be considered a service centre where people, especially from France, visit restaurants and go shopping for cheaper tobacco, alcohol or clothes because of the tax differences between Spain and France. It is also well-known for being one of the largest truck parking areas in Europe, due to La Jonquera being the main Spain–France border crossing point for heavy vehicles (OHFTP 2020). It is also recognized as a focal point for the sex industry for two main reasons: first, because prostitution in Spain is not regulated by law and as such is not illegal and second, because sexual services are cheaper in Spain than France. In turn, Le Perthus is a village located exactly on the Spain–France border, and is hence divided between both countries. Again, the Spanish part receives visitors for the purpose of cheaper purchases. The implementation of the Schengen Area has created this context of cross-border shopping and leisure and as a result the mobility of people and goods has increased. This has stimulated the creation of specialised stores in the border areas, in this case to the benefit of Spain as the cheaper country (Sanguin 2014).

Scholars interested in the Spain–France border have focused their attention on topics such as cross-border cooperation (Lafourcade 1998; Harguindéguy and Bray 2009; Oliveras González 2013; Berzi 2017) and the formation of national identities, as in the case of the Basque borderland (Beck 2008) and the Catalan borderland (Sahlins 1988; Häkli 2001). However, very little attention has been paid to police checks performed on this border, although work has been conducted in recent years by Barbero (2017, 2018). Those studies are mainly an analysis of the legal regulation and the police management of irregular immigration at the Irun–Hendaia border crossing (Basque country), with special interest in deportations and arrests due to violation of immigration laws. To date, there is a lack of academic references to border security enforcement in La Jonquera–Le Perthus. This article attempts to address this research gap by examining police checks as border security practices.

1.2. Border Security as Practice

Currently, the concept of a border goes beyond that of a physical boundary (Bigo and Guild 2005), since they can be located wherever people’s movements are controlled and security checks take place (Balibar 2002). Therefore, borders are not marginal areas, but are situated in the centre of the public sphere (Balibar 2004). Borders have evolved, and with them the everyday practices of border security actors. In fact, in recent years there has been an increase in the tracking of movements across borders, with the creation of buffer zones, the strengthening of monitoring systems, and the addition of extra personnel for policing tasks (Andreas 2003). In Europe, despite the implementation of the Schengen Agreement, EU states wish to maintain their monopoly of control over individuals within their national territory, leading to a situation in which “Schengen nowadays seems to be all about border control and bordering practices driven by concerns of national identity and sovereignty” (van der Woude 2020, p. 111).

In Spain’s internal EU border areas, the Guardia Civil is tasked with preventing illicit trafficking activities, for instance of drugs, merchandise, laundered money and illegal substances (crime control, for non-immigration-related purposes)3. This distinction notwithstanding, some border issues (such as citizenship and immigration) and crime control present similarities as they share the same objectives, namely to provide protection and security (Aas and Bosworth 2013). This gives rise to a merger of immigration control and crime control, what is called “crimmigration” (Stumpf 2006). Previous literature provides evidence of this current border practice (see, e.g., van der Woude et al. 2014; Aas 2011; van der Woude and van der Leun 2017). In any case, defining precisely how borders are currently managed depends on the performance of the actors on the ground, which means exploring border security as practice.

“To overcome the “idealisation” of security, the “essentialisation” of a meaning of security, one of the best approaches seems to be to analyse “security” as a “device”, as a “technique of government”—to use a Foucauldian framework. But security does not emerge from everywhere, it is connected with special “agents” with “professionals” (military agencies, secret services, customs, police forces). And it is only if we follow in detail how they manage to control people, to put them under surveillance, that we will understand how they frame security discourses” (Bigo 2000, p. 176).

In recent years, interest in analysing border security as practice, meaning how the actors involved in the performance of border security act and behave, has led to the development of a special issue to guide a research agenda from this street-level approach. This agenda begins from the objective “to ensure that there is a balance between abstract theoretical work and empirical field-driven analysis” (Côté-Boucher et al. 2014, p. 197). The strategy is to identify and understand the “rules of the game” (i.e., the institutional context that shapes interactions in border encounters), looking at how border actors cooperate and interact regarding these rules (Salter and Mutlu 2013, p. 24). In contrast to policy studies or management studies, approaching border security as practice serves to evaluate how street-level organisations work, establishing links with political and social issues in order to analyse how policy is constructed through their everyday practices (Brodkin 2011).

2. Materials and Methods

For this article, conversation analysis (henceforth CA) (see Sidnell and Stivers 2013) has been used to study 272 videos of the naturally occurring interactions that took place during police checks on traffic heading in the direction of France located in the La Jonquera–Le Perthus border area during summer 2019. The fieldwork and data gathered for this article show that in summer, La Jonquera–Le Perthus is mostly crossed by civilians from France or other European regions who are returning from holidays in Spain, or who have come to this border area in order to buy cheaper goods (Sanguin 2014). This border point is also crossed by people from North Africa who are going to France to visit their relatives or are returning there after spending their holidays in their home countries.

Figure 2.

The AP-7 tollbooth where the Guardia Civil carries out most of the police checks analysed for this research (authors’ data collection).

The authors were allowed to accompany the Guardia Civil at police checks and to record the border encounters with a video camera. This investigation complies with all the ethical rules and provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975. Informed consent forms were issued to explain to police officers and civilians that the research would be recorded, and these were signed to express approval of the recording of videos of their participation in these police checks. In accordance with ethical guidelines, the protection of all participants’ privacy was a priority at all times in this study. Participants who refused to be recorded are not included in the research. Any data that could identify police officers or civilians has been completely anonymized. The transcriptions analysed in this article are depersonalized in the form of the abbreviations PO (police officer) and CI (civilian). Data were transcribed using the Jefferson transcription system (see Jefferson 2004).

Introducing Conversation Analysis

The interaction between professionals (police officers) and lay participants (civilians) can be useful for sharing meaning and establishing a common understanding with regard to border security. From an ethnomethodological perspective, the language used during social interactions is a tool that serves to understand life in society, since “language is not merely a social phenomenon but a social practice” (Sharrock and Watson 1987, p. 433). This is the basis that underpins conversation analysis, a sociological discipline that involves analysing qualitative data, which approaches social practices as social interaction, which is to say, as a series of actions (verbal and nonverbal) occurring while two or more speakers engage in conversation. The objective of CA is to identify and analyse the methods through which people organize their interactions, since every conversation has an order and is managed locally. During a conversation, even a single silence, laugh, or some word or utterance can interfere with a police check encounter when they are treated as meaningful in the course of the interaction. In any case, CA is especially focused on the study of sequential organisation, such as, for example, turn-taking (the order in which speakers talk) and sequence organisation as “the organisation of courses of action enacted through turns-at-talk—coherent, orderly, meaningful successions or ‘sequences’ of action or ‘moves’. Sequences are the vehicle for getting some activity accomplished” (Schegloff 2007, p. 2). In dealing with conversations that occur in institutional contexts, such as police border checks, the actions of the interlocutors are adapted to and fit the context. These interactions are conditioned by the orientation of the members of the institution towards the achievement of objectives and are mainly characterized by asymmetries in participation. In police encounters, the role of the participants in the interaction is predefined. Police officers ask the questions and decide when to begin and end the interaction, while civilians are restricted to answering and following the rules.

The existing literature on CA applied to police settings is a good starting point for developing conversation analysis in the field of border security studies. The previous CA literature has highlighted police interviews (see Stokoe and Edwards 2008; Ferraz de Almeida and Drew 2020) and has often been centred on encounters between police officers and drivers when traffic is stopped, exploring aspects such as how identities, roles and power take part in the production of requests and their counter-requests (Márquez-Reiter et al. 2016). In this realm of police encounters, Shon (2005) analyses the authority of police officers and how they use their coercive power through their interactions. Beyond that, CA can contribute to theoretical discussions about the management of police encounters, and may have implications for policies and practices in the everyday performance of border protection. For example, previous CA studies on police interrogations and interviews have helped to identify how legal relevance can be obtained through actions in interaction. Practices such as formulations, when used to summarize what is said by a suspect during a police interview (Ferraz de Almeida and Drew 2020), and the design of “silly questions” by police officers (Stokoe and Edwards 2008), serve to define the intentionality of a crime and enable its categorization.

CA is conducted in the course of natural, real interactions, meaning that what is being investigated is something that has actually happened, rather than something that is performed especially for the investigation or is based on reports of events such as interviews or field notes. Interviews are not strictly naturally occurring data, and ethnographic field notes depend on and are constrained by the researchers’ competences over what they understand of the data, while CA provides readers direct and equal access to the data (Atkinson and Drew 1979, pp. 22–33). Doing this requires conversations to be recorded with audio and preferably video too, so that both verbal and nonverbal actions can be transcribed and analysed. The most widely used CA transcription system is the Jefferson transcription system (Jefferson 2004), which shows how social talk in interaction is produced. It focuses on both what is said and how it is said, identifying speech features such as intensity, pitch and voice speed, among others. It also allows for the capture of the sequencing of turns (gaps, pauses, overlaps) and other behaviours observable during conversations.

Before proceeding further, it should be noted that CA is a methodology that must employ a deep, intense description of the details that occur during social interactions. Unlike other research approaches that analyse large collections of data, CA focuses on specific examples, as the objective is not to offer a broad, general analysis or to count how many times an oral/nonverbal action is present (statistics), but to analyse representative conversations of the data collection.

3. Results

The following section presents six extracts of conversations between police officers and civilians that are good examples of how certain actions in interaction can influence the course of a border encounter. The analysis is divided into two parts. First, the (lack of) reason for stopping a vehicle. Unlike other police encounters, in checks carried out by the Guardia Civil at La Jonquera–Le Perthus, the officers do not explain the reason for the encounter. However, there are two exceptions in which the reason why they stop vehicles at the border can be identified. Then, the second part is dedicated to practices for avoiding further questioning. As the objective of these police checks is crime control, it has been found that when civilians are not the owners of the vehicle they are driving (i.e., potential suspects of committing a crime), they can still be released from the encounter and avoid further police questioning depending on what they say and the effects of this on the management of the investigation.

Both the case of a (lack of) reason for stopping a car, and the case of (non) ownership of a car share certain interactional features; turn design, taking turns in interaction, position of utterances and its meaning to the encounter (sequence organization), and question-response design, that are somehow treated by the participants as significant and consequently have an impact on the police procedure. Systematic sequential analysis is conducted to describe and interpret the relevance of the participants’ interventions through interaction in the performance of border security at La Jonquera–Le Perthus.

3.1. The (Lack of) Reason for Stopping a Vehicle

In some encounters between the police and the public, such as when stopping traffic, police officers first explain the reason for the encounter, “as a first order of business, then, when officers pull someone over, they typically give their own account, a ‘reason for the stop’, very often using as a format, ‘The reason I stopped you is …’” (Kidwell and Kevoe-Feldman 2018, p. 6). This allows civilians to provide their own account and accept or reject the reason why they have been stopped. In fact, most research on police interaction examines officers reporting events that occurred prior to the interaction itself (see Shon 2005; Kidwell 2018; Kidwell and Kevoe-Feldman 2018; Márquez-Reiter et al. 2016). However, in police checks at La Jonquera–Le Perthus, the reason for stopping a vehicle is justified by inferences of suspicion, based on external appearances or random factors, rather than any previous conduct on the part of civilians (Mora-Rodriguez 2022).

The Guardia Civil officers do not explain the reason why civilians are stopped. Indeed, this absence of explanation is replicated at other EU borders (Brouwer et al. 2018). In the police–civilian interactions analysed here, the police officers stop civilians and then directly ask questions such as “where do you come from?”, or “where are you going?”, without any reference to the reason for the encounter. Civilians ask for an explanation either. Indeed, it is assumed that civilians will obey the law, as most people feel that they should respect and collaborate with the legitimate authorities without putting up resistance (Tyler 2004). This is observed in the data collection for the present research, in which only in two police checks do civilians ask to know why they had been stopped.

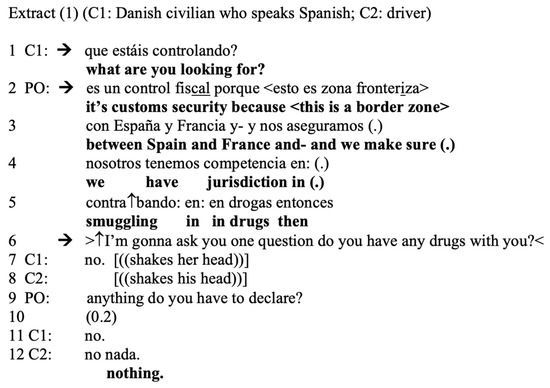

In the first of these two exceptions, two young Danish civilians were stopped. Before the beginning of the conversation transcribed in extract (1) (see Figure 3), one of these two civilians had mentioned that she is from Denmark, but she speaks Spanish well as she lives in Spain.

Figure 3.

Extract (1).

In the police check in extract (1), the Danish civilian who speaks Spanish (C1) becomes the one who asks the questions (line 1). This occurs after she explains that she lives in Spain. It may not be a coincidence that C1 decided at that moment to ask why she had been stopped, as when people have the feeling of belonging to a social group (C1 is someone who lives in Spain and speaks Spanish), they may be more concerned about being treated in an appropriate manner by the authorities (Antrobus et al. 2015; Brouwer et al. 2018).

In lines 2–5, when the PO explains the reason for stopping the car, his turn slows down when he refers to the border context by saying “esto es zona fronteriza” (this is a border zone) (line 2). This highlights that the PO orients to the border context of these police–civilian encounters, despite the fact that these police checks are not considered border controls. Moreover, when the PO mentions the Guardia Civil’s jurisdiction at the border (lines 4–5), the preposition that introduces this information “en” (in), just before “contrabando” (smuggling) and “drogas” (drugs) is prolonged twice, and an additional two breaks “(.)” are observed within this turn. Hence, the PO is slowing down the process of sharing the reason for stopping the car, which may indicate that he is carefully justifying why the Guardia Civil has to interfere with the free movement of people across the border, which also addresses the ambiguity and sensitivities of performing police checks in a border area where border control is no longer permitted.

In contrast, in line 6, when the PO returns to his position as the professional who asks the questions, taking back control of the interaction, the question is asked without any absence of progressivity (“I’m gonna ask you one question do you have any drugs with you?”). The PO produces this utterance quickly, affording no space to counter the reason why they had been stopped. Also, a language shift is produced, directing the question at both C1 and C2 (as C2 speaks English). On this basis, although the PO has granted access to information that explains the presence of the Guardia Civil in this border area, the PO ultimately reorients the conversation towards combating cross-border crime, thus getting back to the police agenda. Therefore, this case is an example of how turns in interaction are locally managed and ultimately adapt to the expected sequence organization of border encounters with crime control as an objective.

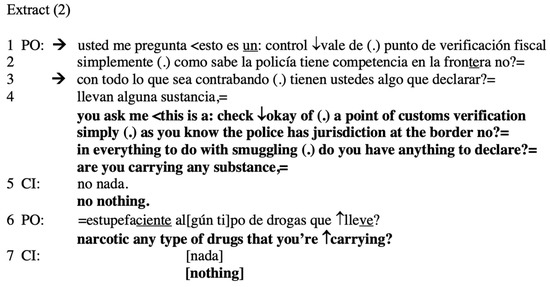

The next extract (2) (see Figure 4) is the second police check in which the reason for stopping the car is provided. This encounter involves two Spanish civilians who inform the PO that they are from a town near to La Jonquera–Le Perthus.

Figure 4.

Extract (2).

After the civilians reported that they are from the area where these police checks take place, the PO decides to explain why civilians were stopped (line 1). Although the PO says that the civilians asked for an explanation, “usted me pregunta” (you ask me) (line 1), the civilians never actually asked for one. By applying CA, it is possible to examine how words are chosen; in this case, the PO has chosen to introduce the reason for stopping people at the La Jonquera–Le Perthus border area by saying “usted me pregunta”, as a way of anticipating a potential question instead of answering an actual one. As occurred in the first extract, the implications of belonging can interfere with the management of the police encounter, with the course of the interaction. As the results of the study by Brouwer et al. (2018) suggest, the reason for stopping a vehicle can diminish the feeling of identity misrecognition. As such, the PO may facilitate access to the reason why these border encounters occur as a preventive measure to avoid the possible negative outcomes that might arise from stopping people who may be aware of their rights at internal EU borders.

When the PO explains the reason for stopping the car (lines 1–3), as many as three breaks within this turn can be observed, and as seen in the analysis of extract (1); this may indicate that the PO is slowing down his justification for stopping vehicles at the border in order to offer a precise explanation and avoid possible misunderstandings. Also, when the PO refers to the border, this is pronounced with a final sharp rising intonation, “en la frontera no?” (at the border no?), indicating that the PO orients to the border location, the same pattern observed in extract (1). The concept that borders can exist whenever and wherever police security checks take place (Balibar 2002) is seen when the PO explicitly stresses the fact that there is a police check because there is a border. In other words, the PO justifies interrupting people’s freedom of movement as being due to their presence in a border area.

Moreover, there are more similarities to be found between extracts (1) and (2). In lines 3–4 and 6, after providing the reason for stopping the car, the PO asks if the civilians have anything illegal to declare, thus affording them no chance to counter his argument. The PO redirects attention to cross-border crime (i.e., finding narcotics, drugs, illegal goods). Hence, while the fact that the CIs are from a town near to the La Jonquera–Le Perthus border area seems to influence the PO into emphasizing that the reason for stopping people is because of the border, this does not change the fact that these police checks are oriented towards preventing crime. In this regard, looking at the details of how people deal with interaction with police at borders provides the “texture of the social relations and networks embedded in the making of border security” (Côté-Boucher et al. 2014, p. 197) as resources to better understand how border actors give meaning to specific situations.

As seen in the analysis of extracts (1) and (2), the officers’ account is formulated in terms of a general practice warranted by their jurisdiction, rather than a decision motivated by the officer’s assessment of the driver’s conduct, as identified in previous studies on social interaction in police traffic stops (Kidwell 2018). This highlights how police border checks are distinctive from other police encounters in public spaces (such as traffic stops), as the former are prospectively oriented, without referring to retro-sequences (Mora-Rodriguez 2022).

3.2. Practices for Avoiding Further Questioning

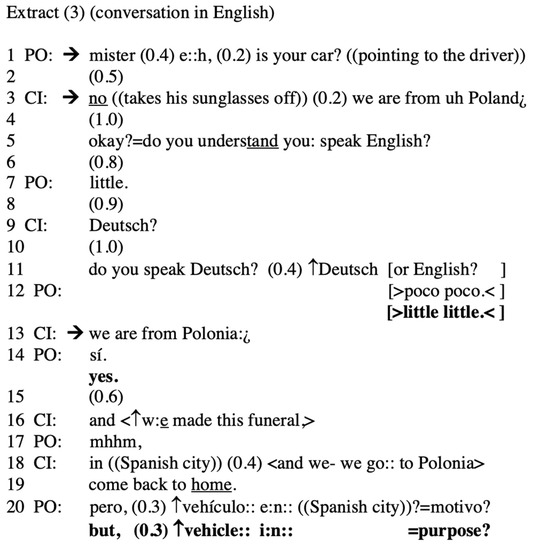

One of the most common questions asked by the Guardia Civil in police checks in La Jonquera–Le Perthus refers to the ownership of the vehicle, as these checks are aimed at preventing crimes, such as identifying stolen vehicles (see Figure 5). Though the Guardia Civil did not find any stolen vehicle in any of the police checks that form part of this research, there were some situations in which civilians avoided further questions about the ownership of the vehicle they were driving, even when they were not its owners. In extract (3) (see Figure 6), two Polish civilians are driving a hearse, something that caught the attention of the police (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A police officer stops a hearse at the AP-7 tollbooth (authors’ data collection).

Figure 6.

Extract (3).

Extract (3) begins after the PO has signalled the vehicle to stop. The PO asks a question while pointing at the driver of the car “mister eh is your car?” (line 1). The PO chooses which of the two occupants is the recipient of the question, this being a way to manage turn-taking known as turn-allocation. However, in line 3, the CI (the passenger) chooses to intervene as the question receiver. This may be explained by the passenger speaking better English than the driver, as is observed during the conversation. In line 3, the CI begins his response with “no”. If the car is not theirs, then there may be a problem, as they could have illegally appropriated a vehicle. Faced with this problem, the CI decides to state that they are from Poland “we are from uh Poland” (line 3). In this intervention, one nonverbal action is highlighted; the CI removes his sunglasses, allowing the PO to look at his eyes. Staring at each other intensifies the relationship between both participants, as it represents how both the CI and the PO “are taking account of the other” (Kendon 1967, p. 48). This occurs just at the moment when the CI informs that they are Polish. In other words, they are European citizens (like the PO), who are crossing an internal EU border. Thus, this is something that they are allowed to do.

In line 3, the CI is providing information that has not been requested by the PO, avoiding a quick follow-up question about the ownership of the car. Then, in line 5, the CI introduces a sequence that serves to establish common ground (the language the participants speak), allowing the civilians more time to avoid answering the PO’s question. The CI’s interactional strategy is evident, for as the PO already asked the question in English (line 1), there was no need to negotiate English as the language of this conversation. With this action, the CI takes the initiative in the interaction, and as in the case of extract (1), it is the civilian who has a better command of the language used and who becomes the one who asks questions to the police. In this regard, extracts (1) and (3) establish a link between language proficiency and assuming the role of questioner in the conversation.

Between line 5 and line 12, the CI and PO have negotiated (confirmed) that they will speak in English. After this, the turn of the CI in line 13 redirects the conversation to its initial point “we are from Polonia”, again drawing the PO’s attention to the civilians’ European citizenship. In line 16, it can be observed that an opportunity had been created to add information, “we made this funeral”, that connects to the PO’s question in line 1, but when the CI considers it most advantageous (and not when the PO wanted). In lines 18–19, the CI refers to their condition as European citizens returning home, “we go to Polonia come back to home”. The emphasis and full stop at the end of the turn show that the CI may claim their right as European citizens to move freely within the Schengen Area as a way to solve the problem (not being the owner of the vehicle) that has existed since the PO’s question in line 1. Finally, in line 20, the PO asks about the CIs’ reason for being in Spain, something the CI has already stated (line 16).

In the remaining conversation, the PO never asks again about the ownership of the car. Hence, the CI used the reference to European citizenship and language negotiation to successfully avoid any questions about ownership of the vehicle by providing information that was not requested, therefore altering the topic proposed in the conversation in the hope of being released from the encounter without significant problems. This is another example of practices that civilians can use in interaction that may have consequences for the police investigation.

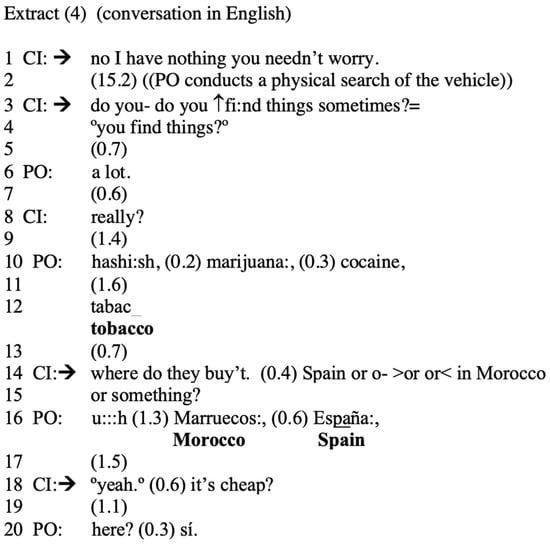

In extract (3), it has been found that civilians are able to switch roles to become the ones asking the questions, making police officers the recipients of their questions. This is also observed in other situations, such as the police encounter in extract (4) (see Figure 7) with a British civilian.

Figure 7.

Extract (4).

Before the beginning of this extract (4), the CI explained he is from England, and he had been in Spain on holiday. After that, the PO started to inspect the vehicle. Since this interaction is in English, this means that the CI is in a superior speaking position in this conversation, since he is a native English speaker, while the PO is not fluent in that language, allowing the CI to even state that the PO does not need to be concerned about him, “no I have nothing you needn’t worry” (line 1). The CI is attempting to influence the PO’s assessment of the vehicle inspection by seeking a quick resolution of suspicion, rather than staying quiet and waiting for the PO to decide whether to further expand the encounter or let him go.

Next, in lines 3–4, the CI switches roles to become the one who asks the questions. The CI asks if the Guardia Civil’s functions at the border are productive, thus assessing their work, “do you- do you find things sometimes?” (line 3). As such, it is the CI who takes the initiative in the interaction, as previously seen in extract (3). In fact, the PO agrees to be evaluated, since in lines 10 and 12 the CI manages to obtain confidential information about the kind of drugs that the Guardia Civil usually find during these border checks. In addition, in lines 14 and 18, the CI keeps asking about the topic introduced in lines 3–4, thus reducing the chances of being asked questions by the PO. Therefore, the “practice turn” allows for an examination of the dynamics that shape contemporary border security (Côté-Boucher et al. 2014), since the CI avoids receiving questions by becoming the questioner himself. This highlights the importance of CA for understanding the actions and activities performed by participants in these border encounters by offering direct access to how turns are sequentially designed in naturally occurring conversation, and how this fits into (or deviates from) the police agenda in their goal of finding grounds for suspicion (Mora-Rodriguez 2022).

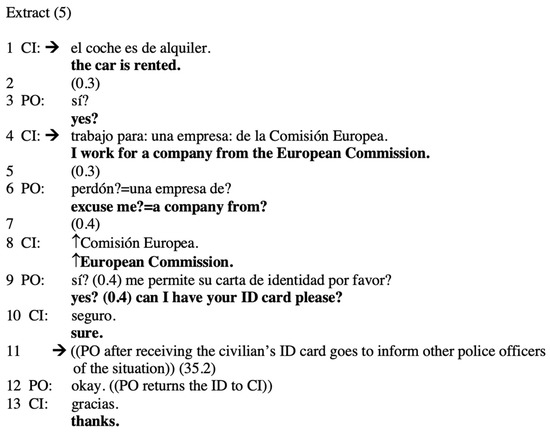

Returning to questions about car ownership, the next extract (5) (see Figure 8) shows the impact of referring to the EU and street-level management.

Figure 8.

Extract (5).

After the initial opening sequence, the PO asks the CI about the ownership of the car. In line 3, after the CI has indicated the car is rented, the PO introduces a continuer token “sí?” (yes?), thus encouraging further conversation since the officer is indicating that the CI’s previous turn was insufficient. This is exactly what the CI does in line 4, informing the PO that the car is related to his job. In particular, he indicates that he works for the European Commission. This exceptionality is noticed in the PO’s next turn (line 6), when the PO introduces two repairs “perdón?” (excuse me?) “una empresa de?” (a company from?), indicating that the CI’s prior turn dealt with a problem that may be repaired. In line 8, in order to repair and solve the problem, the CI stresses his connection with the European Commission, raising his pitch when saying “European Commission”. The PO shows surprise, “sí?” (yes?) (line 9), indicating that the problem arising from the CI’s link with the EU is not solved. In fact, the PO’s next action is to request the CI’s ID, in order to check his identity and his possible relationship with the EU. As there is a problem, in line 11, the PO decides to talk to other police officers who are at the adjacent tollbooth, consulting them for a solution. Consequently, the link between the CI and the European Commission warrants grounds for suspicion, as it requires consultation with other police officers to decide how to proceed with this police check. Hence, the everyday practices of border actors are key to shedding light on contemporary security problems (Côté-Boucher 2013). In particular, in this study it refers to the problem (and ambiguity) between the freedom to cross a border in the Schengen area, where people can move freely, and the fact that people are still being stopped and therefore their freedom of movement is restricted due to not being the owner of the car they are driving. Examination of the practices (actions-in-interaction) in the police encounter in extract (5) reveals very specific microdetails that shed light on how civilians deal with the problem of being treated as potential suspects for the mere fact of driving in a border area in which systematic border control has been removed (see Mora-Rodriguez 2022), rather than on the basis of suspicions motivated by previous activities. For example, it is possible to identify how police officers are unwilling to accept the simple answer that a car is rented and require further explanation against which to assess their suspicion. In addition, the civilian, instead of simply mentioning that the car is rented for work, explicitly describes his link with the European Commission, the executive arm of the EU. The CI addresses the problem of not being the owner of the car by adding information that was not requested but that he considers relevant and meaningful to dismiss suspicion and thus avoid further questioning, a practice observed in previous extracts. At the same time, it is the link with the EU that arouses suspicion, which implies that the PO may need to make a discretionary decision to resolve the suspicion, that is, to expand the encounter in search for further grounds of suspicion, or to finally release the CI from suspicion. Consequently, the contemporary border security problem that CA sheds light on is how participants make autonomous decisions and choices in the way they deal with suspicion (Mora-Rodriguez 2022).

In fact, in line 12, following the consultation with the other Guardia Civil officers, the PO says “okay”, giving a favourable assessment of the CI’s connection with the EU, without asking anything else. The PO consequently backs away from the driver’s window, allowing the CI to continue his journey. Therefore, the reference to the European Commission, despite being treated as a problem, as grounds for suspicion by the PO, was finally key to finishing the police check with a positive result for the CI, as he avoided having to answer any crime-related question or having to prove the car is rented or being asked to open the trunk of the car for a physical inspection. Beyond this, the conversation in extract (5) reveals the effect of mentioning the EU (i.e., a governmental institution) in a police check, adding a cause for suspicion, and offering insights into influences on police decision-making in crime control.

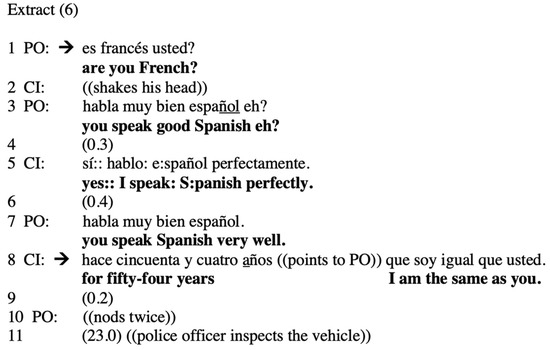

Another example of how participants mitigate suspicion and thus avoid further police questioning is the following extract (6) (see Figure 9), in which the stopped civilian claims to live in France, which has an impact on the interaction.

Figure 9.

Extract (6).

Extract (6) begins after 57 seconds of the conversation. While a police officer inspects the interior of the vehicle, another police officer (PO), who until then has participated very little, decides to begin an interaction with the CI. After asking the CI where he was travelling from and for his place of residence (France), in line 1 the PO asks about the CI’s citizenship, “es francés usted?” (are you French?). This can be considered an example of crimmigration in practice, asking about immigration issues during a crime check, a trend in the securitisation of EU internal borders since the abolishment of border control (see van der Woude and van Berlo 2015). After that, despite the CI’s response with a negative gesture (shakes his head) (line 2), the PO does not cease in his attempts to make the CI engage in the conversation, praising the CI both in line 3 “habla muy bien español eh?” (you speak good Spanish eh?) and line 7 “habla muy bien español” (you speak Spanish very well). In CA terms, this is known as a verbal “gift”, a positive politeness strategy designed to contribute to the generation of a topic (Svennevig 1999). In practice, the PO is moving the interaction towards solving the problem arising from how the CI lives in France, but speaks perfect Spanish. In line 8, as a measure to resolve the problem, the CI communicates a message of belonging to the PO, “soy igual que usted” (I am the same as you). With this message, the CI informs the PO that he is a Spanish citizen despite living in France, which has consequences for the interaction. Specifically, it leaves the PO speechless and reacting only with head movements (nods twice) (line 10). In addition, there is a long, 23 seconds silence in the conversation as the vehicle inspection is in progress (line 11). Therefore, the CI manages to avoid further questions from the PO related to immigration status (or any type of question), redirecting the attention of the encounter to crime control (vehicle inspection).

In this light, the example of the police check in extract (6) shows that some actions-in-interaction, such as sharing a sense of belonging (in this case to Spain), can be used by civilians as a resource to prevent police officers from gathering more information about them, as a solution to problems or possible inconsistencies arising from conversations with the police.

4. Conclusions

The application of CA shows that the nature of border security encounters at La Jonquera–Le Perthus is shaped and conditioned by specific circumstances that occur through actions and behaviours in interaction, in alignment with the perspective of studying border security as a practice. Border security is constructed through everyday practices that can be understood by examining how actors in such encounters perform their roles and conceive their identities (Côté-Boucher et al. 2014). From this perspective, it is possible to examine which actions-in-interaction are relevant for the development of the encounter and to achieve interactional coherence when the participants treat them as significant for the course of the interaction. The results manifest that language practices can have an impact on the moment-by-moment dynamic of crime control. In particular, this article presents examples of actions and sequences that can substantially interfere with the police agenda in the management of border security. When these situations occur, CA presents an opportunity to analyse how these actions are locally managed, that is, how words are chosen, how turns are sequentially designed and how they adapt to the sequence organization of border encounters.

The focus of this article provides specific information on the moment of the conversation when actions that have an impact on the interaction emerge, describing and examining how they are consequential for the police check. Likewise, CA shows how border actors provide meaning to border security practices when the underlying intention of their actions is to resolve the encounter, that is, resolve the suspicion that civilians might be committing a cross-border crime, analysing how sequences and turns-in-talk are constructed to accomplish goals (i.e., resolve suspicion). When participants are trying to make sense of problematic issues (e.g., lack of reason for the encounter, and non-ownership of the car), trouble-source speakers can initiate turns to overcome and resolve those problems. This can represent a shift in the agenda of these institutional encounters, leading to modifications of turns and roles (e.g., civilians becoming the questioners), with the goal of achieving their objectives in the interaction. On the one hand, police officers may need to justify and provide an account of their reasons for stopping people who, according to the Schengen rules, are free to cross Schengen borders, and CA provides the specific details of how and when they do so, and what linguistic resources they use for the purpose. Consequently, CA provides an approach to observe not only that police officers have discretionary authority to choose whether to stop civilians or not, but also that they have the right to make a discretionary decision as to how and when to account for the reason to interrupt and interfere with the right to freedom of movement. From the civilians’ perspective, their objective is to avoid being asked crime-related questions by the police, such as those about car ownership. In this regard, this study demonstrates how certain factors and actions can lead civilians to avoid further questioning, which can interfere with the process of resolving suspicion that anyone stopped at police border checks needs to deal with through talk. Therefore, this article proves that CA can be used to identify the specific moments when police officers and civilians understand actions to be significant for the progressivity of the border security encounter.

Scholars interested in the study of the securitization of borders are encouraged to apply CA in order to gain additional information on the nature of police–civilian interactions, by taking a qualitative research perspective that facilitates detection of how actors invoke meanings of border security through actions in interaction. In this regard, the use of CA can be useful to “overcome the ‘idealisation’ of security (…). If we refuse to do this sociological work, if we try only to analyse the inter-discursive practices, we will ‘intellectualise’ the securitization” (Bigo 2000, p. 176). To this end, CA provides an empirical approach that addresses new debates on border security and its empirical practices on the ground, recognizing the role that each single action-in-interaction plays in dealing with the constraints associated with the rules governing cross-border crime control. In other words, the rules that shape and condition the interactions that occur between law enforcement agents and border crossers. As such, CA serves to observe how “the rules of the game” are managed through language in practice in depth.

Ultimately, the discipline of CA examines practices solely and exclusively for the purposes of better understanding how actors behave, and how they give meaning to their everyday actions and activities. Also, and importantly, CA sheds light on how these actions become visible during the encounter, and is essential for fully understanding police routines and the role of people when engaging with border security. Nonetheless, it must be recognized that the use of CA has some limitations, as the selection of video recordings and the way they are transcribed can be subjective, and also sensitive to overgeneralisations. Analysis of the recorded data limits the possibility of obtaining further understanding about the participants’ perceptions of freedom of movement in the Schengen Area, of police authority and of the decision to stop vehicles or not, which could have been obtained by interviewing the two parties. Hence, future research on border security as a practice could benefit from the adoption of both methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-R.; Methodology, M.M.-R. and C.R.-C.; Validation, M.M.-R. and C.R.-C.; Formal analysis, M.M.-R.; Investigation, M.M.-R.; Resources, M.M.-R.; Data curation, M.M.-R.; Writing—original draft, M.M.-R.; Writing—review & editing, C.R.-C.; Visualization, M.M.-R.; Supervision, C.R.-C.; Project administration, M.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and following personal data protection protocols.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

According to the protocol accepted by the participants of this research, the entire data set is only available to the authors of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The Schengen Area comprises 26 European countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. |

| 2 | Article 23. Regulation (EU) 2016/399 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2016 on a Union Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code). |

| 3 | Organic law 2/1986 of 13 March on State Security Forces, in its article 12 establishes that the Guardia Civil can exercise the powers of state fiscal protection and actions aimed at preventing and prosecuting smuggling activities (i.e., crime control). |

| 4 | Since 1 September 2021, the AP-7 highway has been free. |

References

- Aas, Katja Franco. 2011. ‘Crimmigrant’ Bodies and Bona Fide Travelers: Surveillance, Citizenship and Global Governance. Theoretical Criminology 15: 331–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, Katja Franco, and Mary Bosworth, eds. 2013. The Borders of Punishment: Migration, Citizenship, and Social Exclusion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, Peter. 2003. Redrawing the Line: Borders and Security in the Twenty-First Century. International Security 28: 78–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrobus, Emma, Ben Bradford, Kristina Murphy, and Elise Sargeant. 2015. Community Norms, Procedural Justice, and the Public’s Perceptions of Police Legitimacy. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 31: 151–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, John Maxwell, and Paul Drew. 1979. Order in Court: The Organisation of Verbal Interaction in Judicial Settings. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Balibar, Étienne. 2002. Politics and the Other Scene. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Balibar, Étienne. 2004. We, the People of Europe?: Reflections on Transnational Citizenship. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero, Iker. 2017. La Readmisión de Extranjeros en Situación Irregular entre Estados Miembros: Consecuencias Empírico-Jurídicas de la Gestión Policial de las Fronteras Internas. Cuadernos Electrónicos de Filosofía del Derecho 36: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, Iker. 2018. The European Union Never got Rid of Its Internal Controls. A Case Study of Detention and Readmission in the French-Spanish Border. European Journal of Migration and Law 20: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Jan Mansvelt. 2008. Has the Basque Borderland Become more Basque after Opening the Franco-Spanish Border? National Identities 10: 373–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdah, Jean-François. 2009. Pyrenees without Frontiers: The French-Spanish Border in Modern Times, 17th to 20th Centuries. In Frontiers, Regions and Identities in Europe. Edited by Steven. G. Ellis and Raingard Eβer. Pisa: Plus-Pisa University Press, pp. 163–84. [Google Scholar]

- Berzi, Matteo. 2017. The Cross-Border Reterritorialization Concept Revisited: The Territorialist Approach Applied to the Case of Cerdanya on the French-Spanish Border. European Planning Studies 25: 1575–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigo, Didier. 2000. When Two Become One: Internal and External Securitisations in Europe. In International Relations Theory and the Politics of European Integration: Power, Security and Community. Edited by Morten Kelstrup and Michael Williams. London: Routledge, pp. 171–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bigo, Didier, and Elspeth Guild. 2005. Controlling Frontiers: Free Movement into and Within Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin, Evelyn Z. 2011. Putting Street-level Organizations First: New Directions for Social Policy and Management Research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21: 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, Jelmer, Maartje Van der Woude, and Joanne Van der Leun. 2018. Border Policing, Procedural Justice and Belonging: The Legitimacy of (Cr)immigration Controls in Border Areas. The British Journal of Criminology 58: 624–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté-Boucher, Karine. 2013. The Micro-Politics of Border Control: Internal Struggles at Canadian Customs. Ph.D. dissertation, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Boucher, Karine, Federica Infantino, and Mark B. Salter. 2014. Border Security as Practice: An Agenda for Research. Security Dialogue 45: 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz de Almeida, Fabio, and Paul Drew. 2020. The Fabric of Law-in-Action: ‘Formulating’ the Suspect’s Account During Police Interviews in England. International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law 27: 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkli, Jouni. 2001. The Politics of Belonging: Complexities of Identity in the Catalan Borderlands. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 83: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harguindéguy, Jean-Baptiste, and Zoé Bray. 2009. Does Cross-Border Cooperation Empower European Regions? The Case of INTERREG III-A France–Spain. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 27: 747–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, Gail. 2004. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Conversation Analysis. Studies from the First Generation. Edited by Gene Lerner. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kendon, Adam. 1967. Some Functions of Gaze-Direction in Social Interaction. Acta Psychologica 26: 22–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, Mardi. 2018. Early alignment in police traffic stops. Research on Language and Social Interaction 51: 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, Mardi, and Heidi Kevoe-Feldman. 2018. Making an Impression in Traffic Stops: Citizens’ Volunteered Accounts in Two Positions. Discourse Studies 20: 613–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafourcade, Maïté. 1998. ‘La Frontière Franco-Espagnole, Lieu de Conflits Interétaqiues et de Collaboration Interrégionale’. Biarritz: Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux. [Google Scholar]

- Markuszewska, Iwona, Minna Tanskanen, and Josep Vila Subirós. 2016. Boundaries from Borders: Cross-Border Relationships in the Context of the Mental Perception of a Borderline—Experiences from Spanish-French and Polish-German Border Twin Towns. Quaestiones Geographicae 35: 105–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Reiter, Rosina, Kristina Ganchenko, and Anna Charalambidou. 2016. Requests and Counters in Russian Traffic Police Officer-Citizen Encounters: Face and Identity Implications. Pragmatics and Society 7: 512–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Rodriguez, Michael. 2022. Resolving Suspicion Moment-by-Moment. The Overall Structural Organization of Police Encounters in the Spain-France Border Area. Language & Communication 87: 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio Hispano-Francés de Tráfico en los Pirineos [nº9]. 2020. Ministerio de Transportes, Movilidad y Agenda Urbana. Available online: https://www.mitma.gob.es/informacion-para-el-ciudadano/observatorios/observatorios-de-transporte-internacional/observatorio-hispano-frances-de-trafico-en-los-pirineos (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Oliveras González, Xavier. 2013. Cross-Border Cooperation in Cerdanya (Spain-France Border). Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 62: 435–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, Peter. 1988. The Nation in the Village: State-Building and Communal Struggles in the Catalan Borderland During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. The Journal of Modern History 60: 234–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, Mark B., and Can E. Mutlu, eds. 2013. Research Methods in Critical Security Studies: An Introduction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sanguin, Andre-Louis. 2014. The Schengen Effects at the EU’s Inner Borders: Cheaper Stores and Large-Scale Legal Prostitution. The Case of the La Jonquera Area (Catalonia-Spain). In The New European Frontiers: Social and Spatial (Re)Integration Issues in Multicultural and Border Regions. Edited by Milan Bufon, Julian Minghi and Anssi Paasi. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholar Publishing, pp. 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2007. Sequence Organization in Interaction. A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock, Wes W., and D. Rod Watson. 1987. Talk and Police Work: Notes on the Traffic in Information. In Working with Language: A Multidisciplinary Consideration of Language Use in Work Contexts. Edited by Hywel Coleman. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 431–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shon, Phillip Chong Ho. 2005. “I’d Grab the S-O-B by his Hair and Yank him out the Window”: The Fraternal Order of Warnings and Threats in Police-Citizen Encounters. Discourse and Society 16: 829–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidnell, Jack, and Tanya Stivers. 2013. The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, Elizabeth, and Derek Edwards. 2008. ‘Did You Have Permission to Smash your Neighbour’s Door?’ Silly Questions and their Answers in Police—Suspects Interrogations. Discourse Studies 10: 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, Juliet. 2006. The Crimmigration Crisis: Immigrants, Crime, and Sovereign Power. American University Law Review 56: 367–419. [Google Scholar]

- Svennevig, Jan. 1999. Getting Acquainted in Conversation. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, Tom R. 2004. Enhancing police legitimacy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 593: 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, Maartje. 2020. A Patchwork of Intra-Schengen Policing: Border Games over National Identity and National Sovereignty. Theoretical Criminology 24: 110–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, Maartje, and Joanne van der Leun. 2017. Crimmigration Checks in the Internal Border Areas of the EU: Finding the Discretion that Matters. European Journal of Criminology 14: 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, Maartje, and Patrick van Berlo. 2015. Crimmigration at the Internal Borders of Europe? Examining the Schengen Governance Package. Utrecht Law Review 11: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, Maartje, Joanne van der Leun, and Jo-Anne A. Nijland. 2014. Crimmigration in the Netherlands. Law and Social Inquiry 39: 560–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).