Sailing Uncharted Waters with Old Boats? COVID-19 and the Digitalization and Professionalization of Presidential Campaigns in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Election Campaigning: Which Influence on Digitalization and Professionalization?

3. Methodology

3.1. Variable Operationalization

3.1.1. Digitalization

3.1.2. Online Competition

3.1.3. Professionalization

4. Results

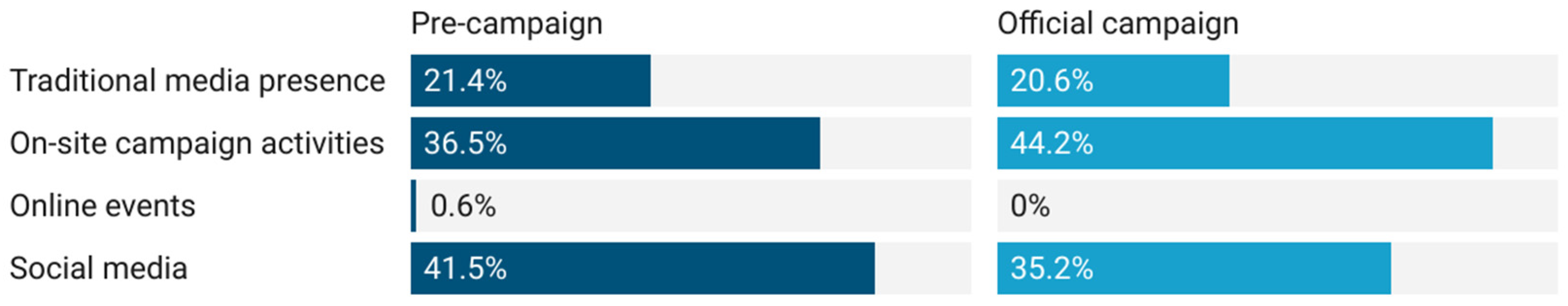

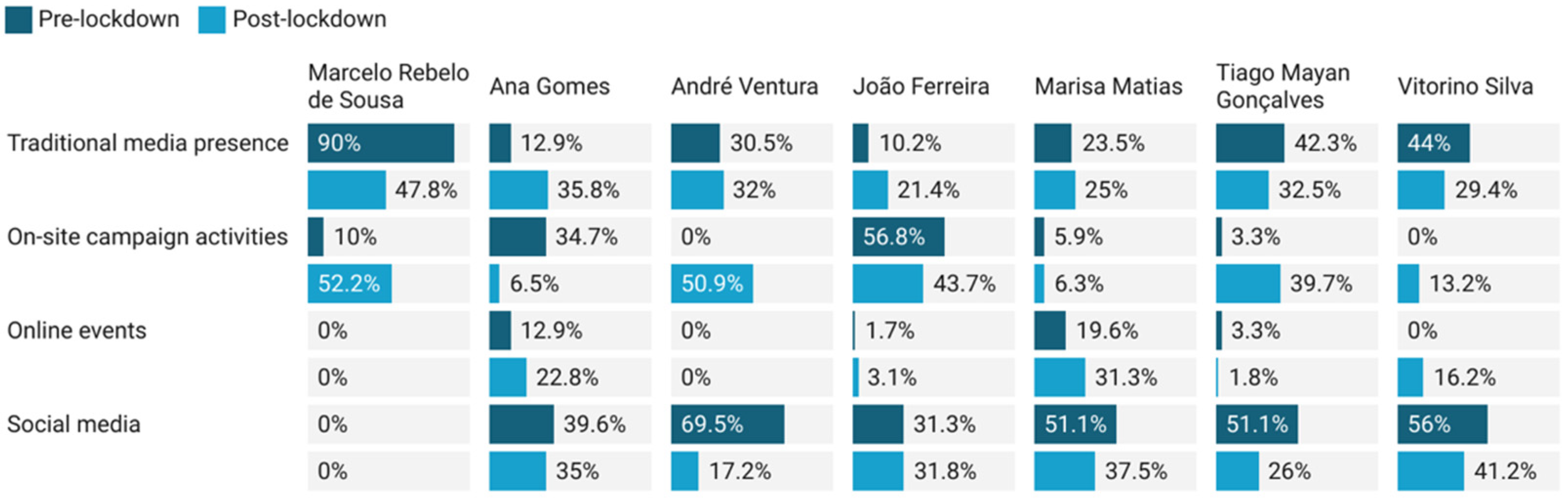

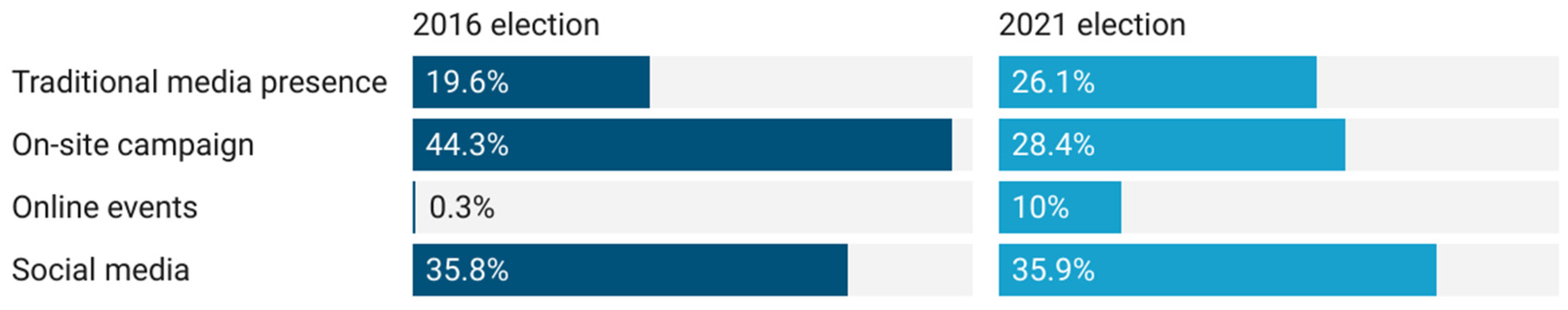

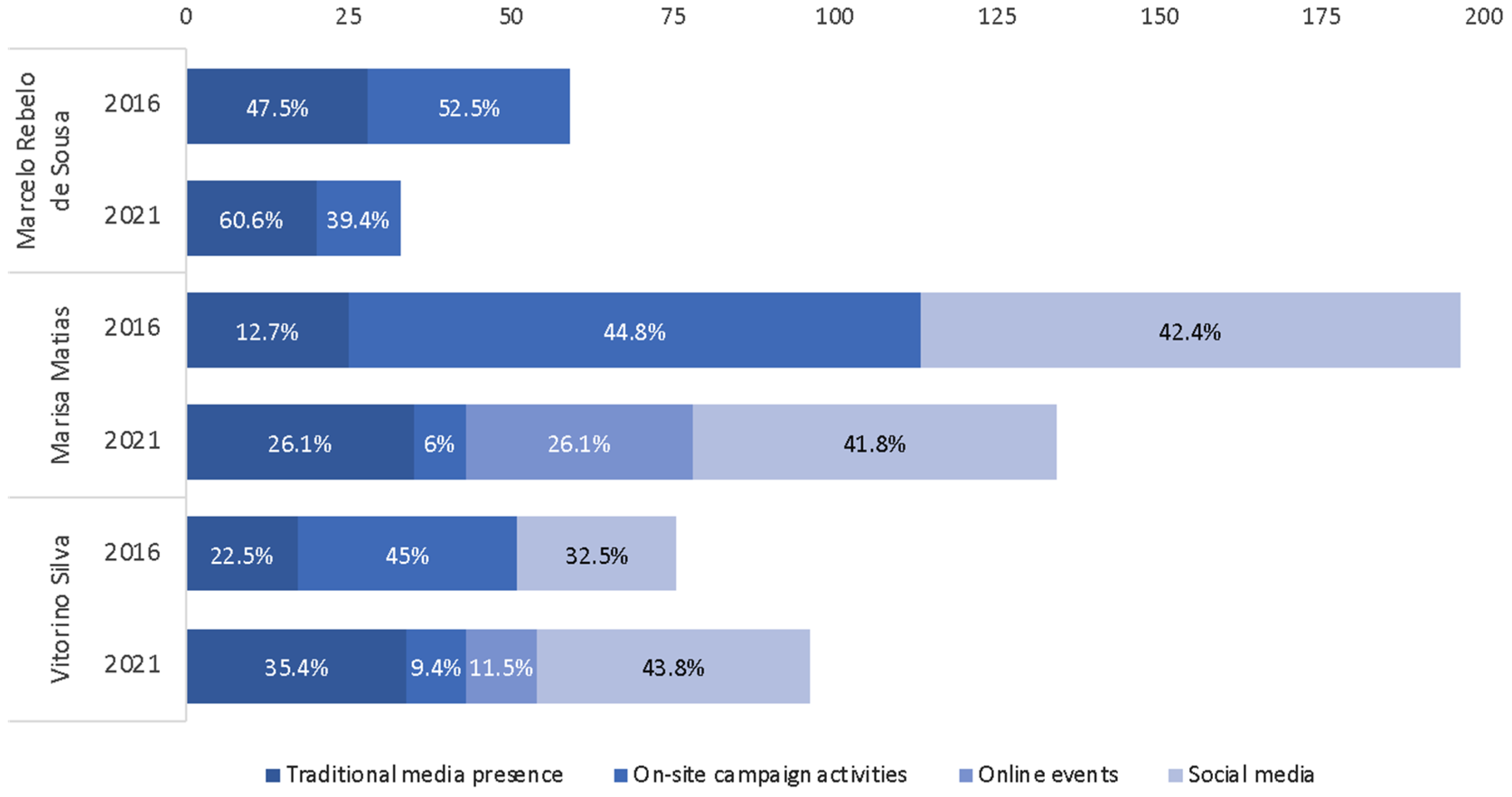

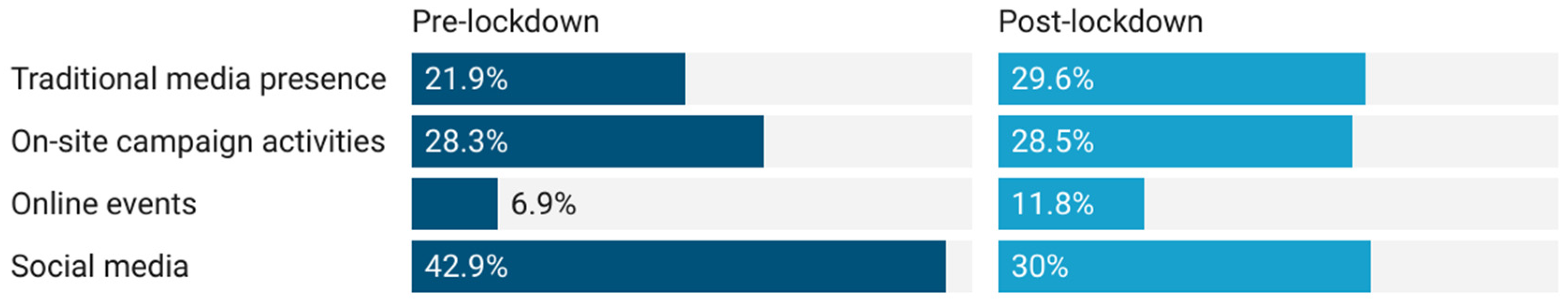

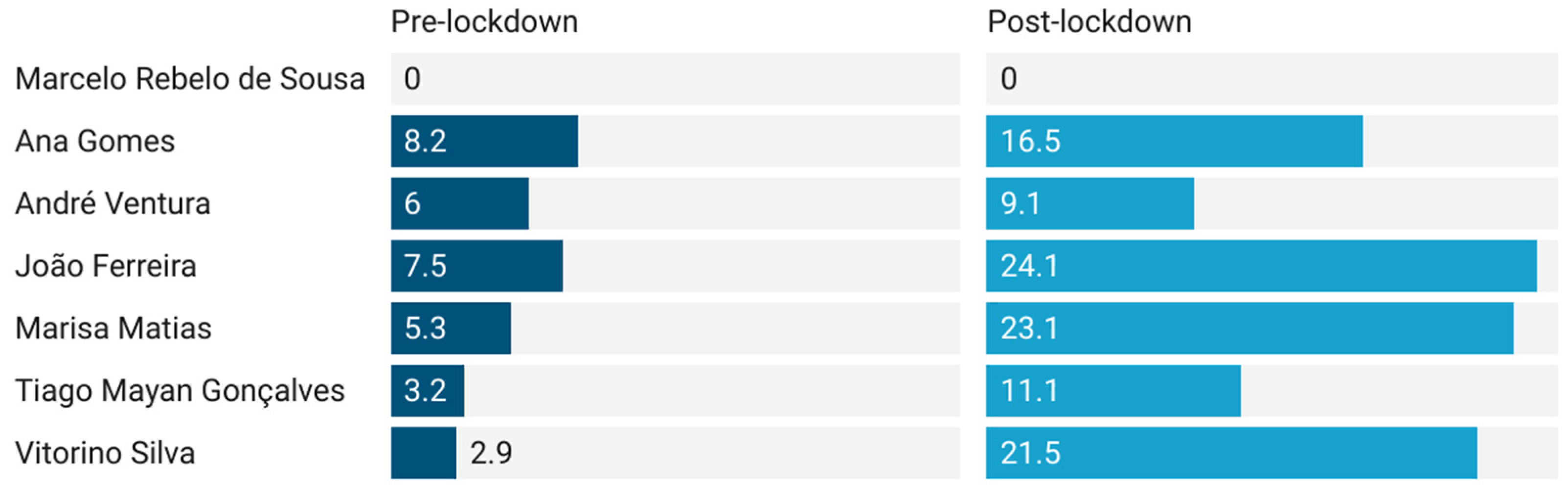

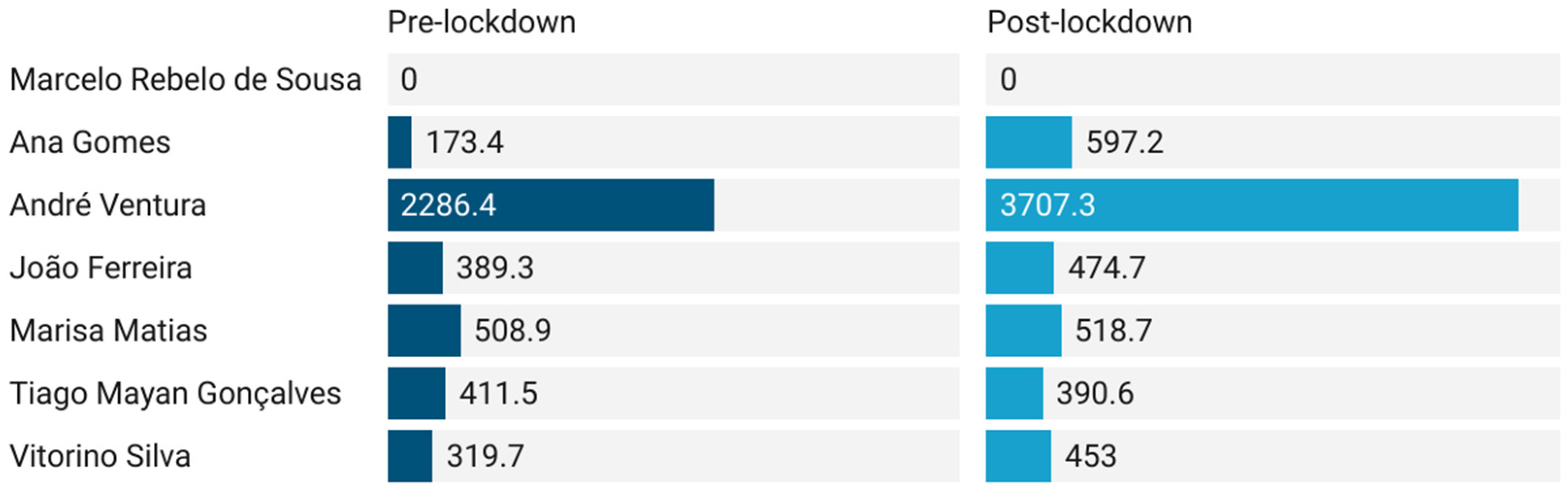

4.1. Digitalization

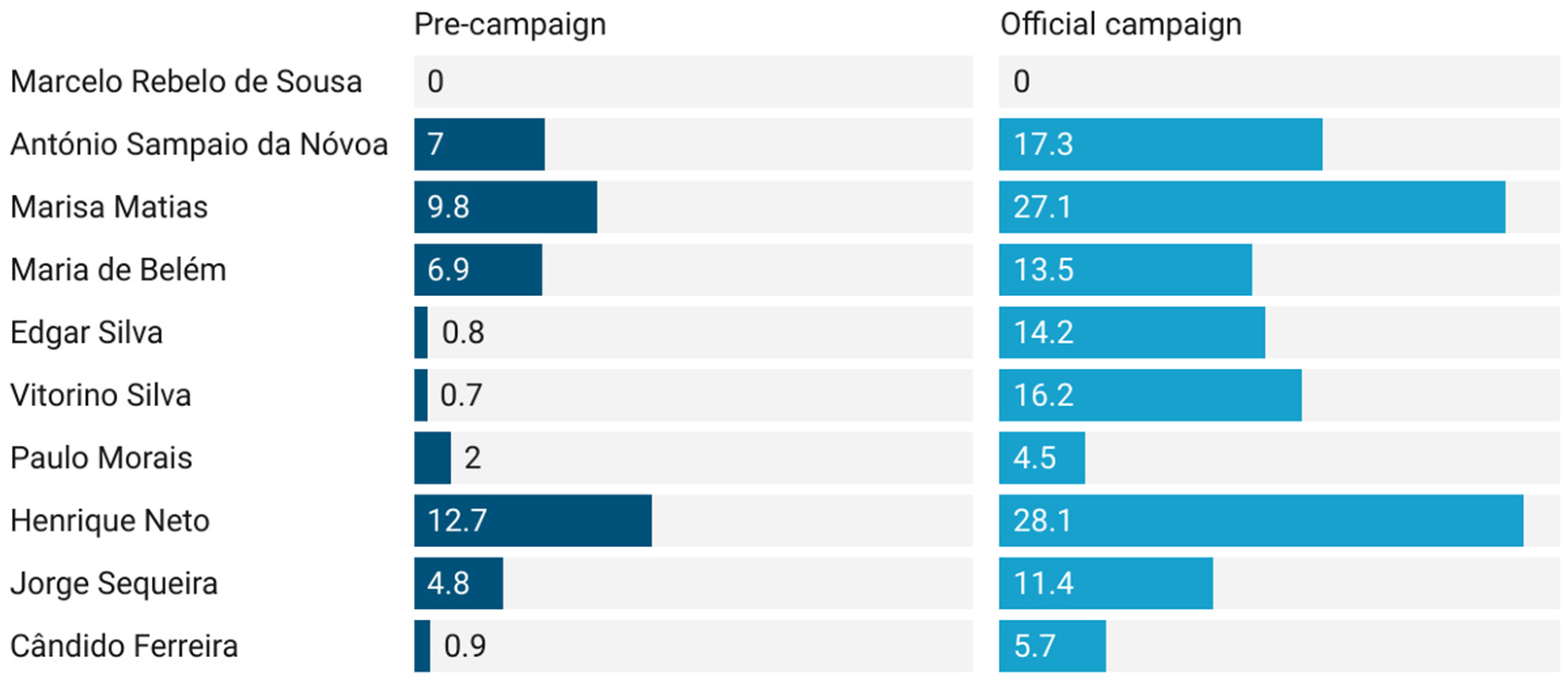

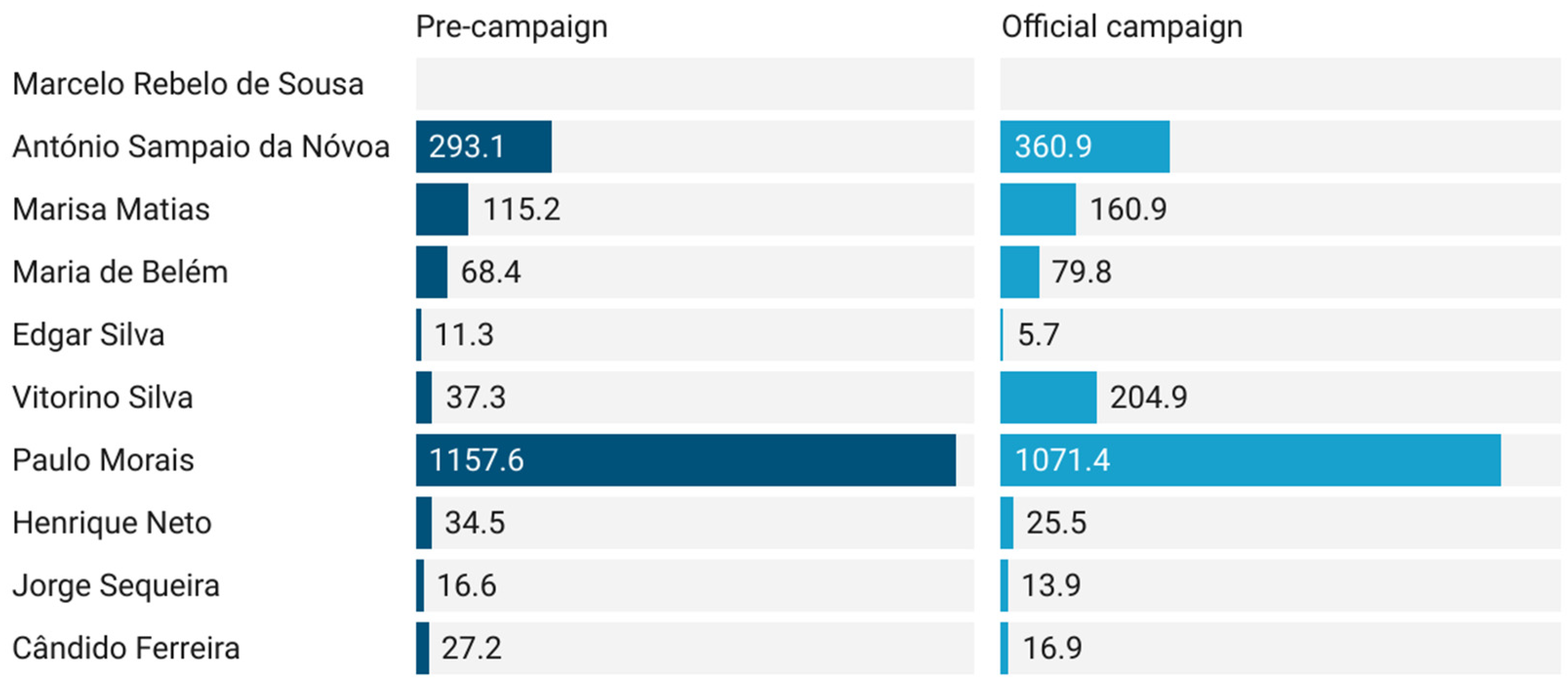

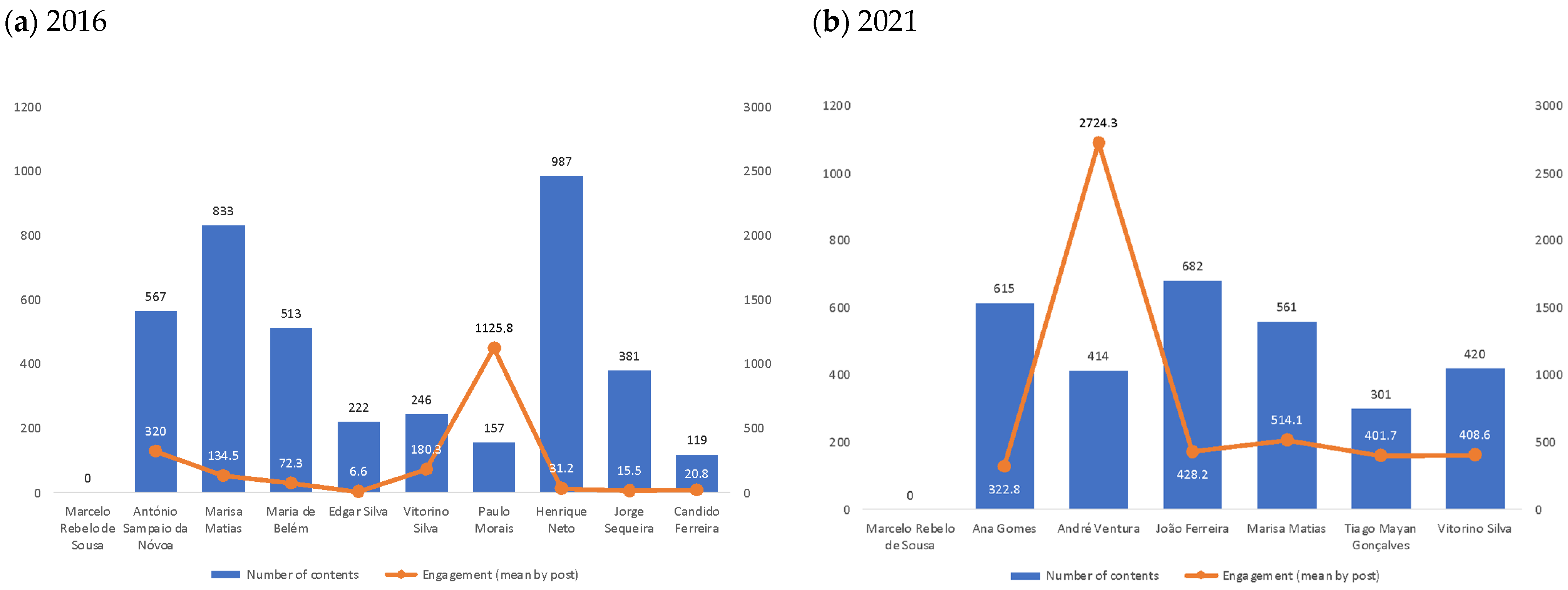

4.2. Online Competition

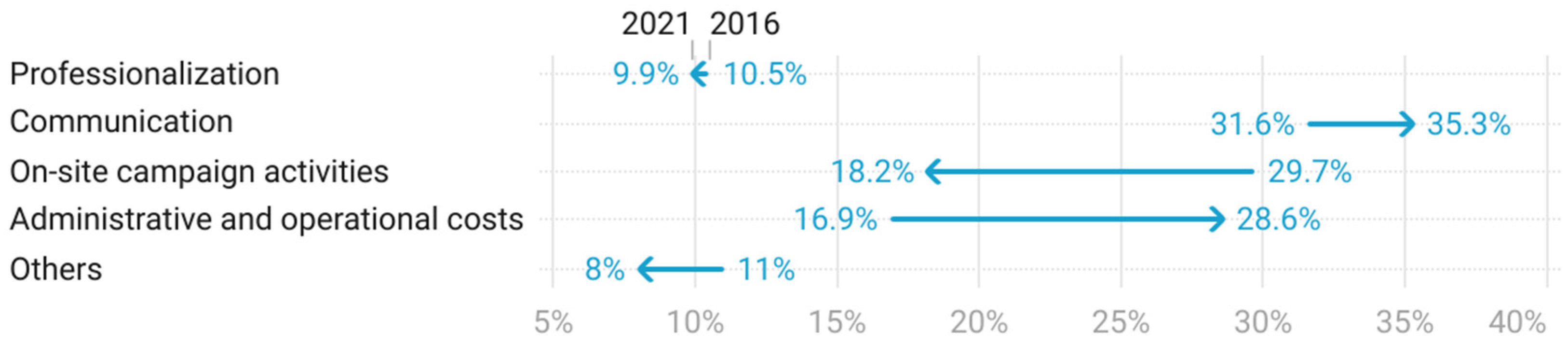

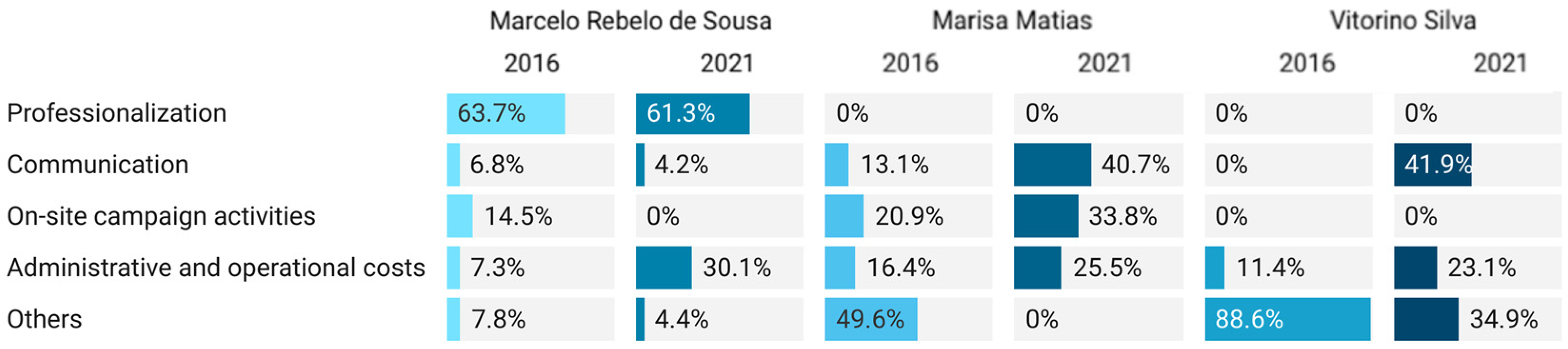

4.3. Professionalization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Professionalization | Communication | Events | Administrative and Operational Costs | Others | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Change | |

| Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa | 1500 (6%) | 15,276 (61.2%) | 3500 (14%) | 1047 (4.2%) | 0 | 0 | 16,000 (64%) | 7504 (30.1%) | 4000 (16%) | 1100 (4.4%) | 25,000 | 24,927 | −73 |

| Ana Gomes | 17,500 (32.7%) | 44,477 (32.8%) | 17,000 (31.7%) | 25,573 (18.9%) | 8500 (15.9%) | 31,051 (22.9%) | 5000 (9.4%) | 34,352 (25.4%) | 5500 (10.3%) | 0 | 53,500 | 135,453 | +81,953 |

| André Ventura | 25,000 (15.6%) | 36,900 (18.4%) | 75,000 (46.8%) | 56,734 (28.3%) | 40,000 (25%) | 6123 (3%) | 10,000 (6.3%) | 21,013 (10.4%) | 10,000 (6.3%) | 80,343 (39.9%) | 160,000 | 201,112 | +41,112 |

| João Ferreira | 0 | 0 | 225,000 (50%) | 110,921 (40.4%) | 35,000 (7.8%) | 24,705 (9%) | 170,000 (37.8%) | 138,637 (50.6%) | 20,000 (4.4%) | 0 | 450,000 | 274,264 | −175,736 |

| Marisa Matias | 0 | 0 | 155,473 (60.6%) | 145,514 (41%) | 52,466 (20.3%) | 121,079 (33.7%) | 48,679 (19%) | 91,279 (25.5%) | 0 | 0 | 256,618 | 357,872 | +101,255 |

| Tiago Mayan Gonçalves | 10,450 (27.2%) | 6765 (14.3%) | 18,000 (46.8%) | 27,204 (57.5%) | 3000 (7.8%) | 8194 (17.4%) | 5500 (14.3%) | 5120 (10.8%) | 1500 (3.9%) | 0 | 38,450 | 47,284 | +8834 |

| Vitorino Silva | 3000 (18.7%) | 0 | 6000 (37.5%) | 3000 (41.9%) | 0 | 0 | 1000 (6.3%) | 1655 (23.2%) | 6000 (37.5%) | 2500 (34.9%) | 16,000 | 7155 | −8845 |

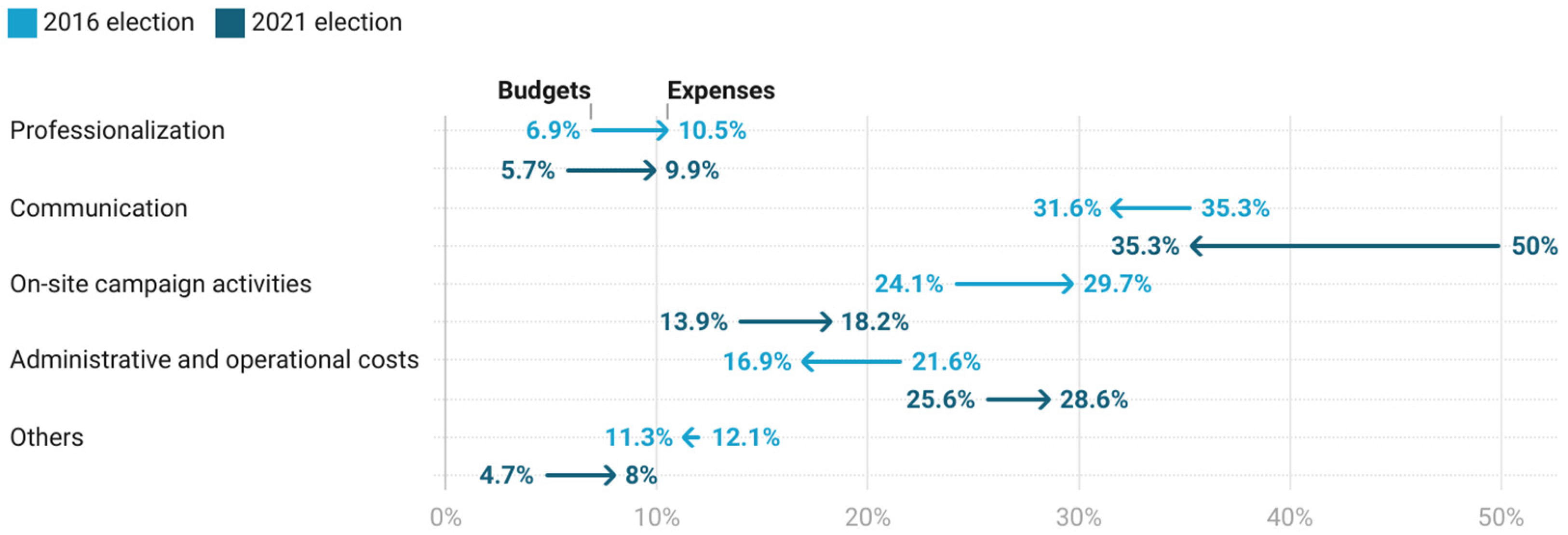

| Total | 57,450 (5.8%) | 103,418 (9.9%) | 499,973 (50%) | 369.993 (35.3%) | 138,966 (13.9%) | 191,152 (18.2%) | 256,179 (25.6%) | 299,560 (28.6%) | 47,000 (4.7%) | 83,943 (8%) | 999,568 (100%) | 1,048,067 (100%) | +48,499 (4.9%) |

| Professionalization | Communication | Events | Administrative and Operational Costs | Others | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Budget | Expenses | Change | |

| Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa | 20,000 (12.7%) | 114,376 (63.6%) | 55,000 (35.2%) | 12,121 (6.8%) | 20,000 (12.7%) | 25,945 (14.5%) | 40,000 (25.4%) | 13,045 (7.3%) | 22,000 (14%) | 14,019 (7.8%) | 157,179 | 179,507 | +22,328 |

| António Sampaio da Nóvoa | 50,000 (6.7%) | 46,475 (5%) | 240,000 (32.3%) | 345,776 (37.4%) | 120,000 (16.2%) | 354,146 (38.3%) | 200,000 (27%) | 150,937 (16.3%) | 132,000 (17.8%) | 27,157 (3%) | 742,000 | 924,493 | +182,493 |

| Marisa Matias | 0 | 0 | 128,301 (28.2%) | 78,709 (13.1%) | 143,910 (31.7%) | 125,810 (20.7%) | 47,448 (10.4%) | 98,649 (16.2%) | 135,000 (2.7%) | 298,545 (49.1%) | 454,659 | 607,715 | +153,056 |

| Maria de Belém Roseira | 84,271 (13%) | 56,478 (10.4%) | 195,877 (30.1%) | 183,634 (33.9%) | 267,968 (41.2%) | 236,687 (43.7%) | 99,613 (15.3%) | 60,716 (11.2%) | 2268 (0.4%) | 4380 (0.8%) | 650,000 | 541,896 | −108,104 |

| Edgar Silva | 0 | 0 | 400,000 (53.3%) | 276,281 (47.5%) | 185,000 (24.7%) | 144,659 (24.9%) | 145,000 (19.3%) | 159,189 (27.4%) | 20,000 (2.7%) | 984 (0.2%) | 750,000 | 581,114 | +168,886 |

| Vitorino Silva | 2000 (4%) | 0 | 13,000 (26%) | 0 | 9000 (18%) | 0 | 10,000 (20%) | 926 (11.5%) | 16,000 (32%) | 7229 (88.5%) | 50,000 | 8159 | +41,841 |

| Paulo de Morais | 13,714 (23%) | 13,714 (23%) | 16,716 (28%) | 16,716 (28%) | 6423 (10.8%) | 6423 (10.8%) | 22,684 (38%) | 22,684 (38%) | 0 | 0 | 59,539 | 59,539 | = |

| Henrique Neto | 14,000 (5.1%) | 77,509 (31.2%) | 67,000 (24.3%) | 91,862 (39.9%) | 28,000 (10.2%) | 45,106 (18.1%) | 140,000 (50.9%) | 31,288 (12.6%) | 26,000 (9.5%) | 3005 (1.2%) | 275,000 | 248,771 | +26,226 |

| Jorge Sequeira | 15,000 (12.1%) | 3690 (61.2%) | 43,000 (34.8%) | 425 (7.1%) | 13,000 (10.5%) | 270 (4.5%) | 8500 (6.9%) | 40 (0.7%) | 44,000 (35.6%) | 1600 (26.6%) | 123,500 | 6026 | +117,474 |

| Cândido Ferreira | 30,000 (50%) | 23,207 (75.8%) | 14,000 (23.3%) | 0 | 6000 (10%) | 5456 (17.9%) | 4000 (6.7%) | 0 | 6000 (6.7%) | 1968 (6.4%) | 60,000 | 30,632 | −29,368 |

| Total | 228,986 (6.9%) | 335,451 (10.5%) | 1,172,895 (35.3%) | 1,005,527 (31.6%) | 799,302 (24%) | 944,506 (29.7%) | 717,246 (21.5%) | 537,482 (16.8%) | 403,268 (12.2%) | 358,890 (11.3%) | 3,321,698 (100%) | 3,181,858 (100%) | −139,840 (−4.3%) |

| 1 | We leave aside campaign websites, following Yang and Kim’s (2017) and Lev-On and Haleva-Amir’s (2018) assumption that the center of gravity for online politics has now shifted towards social media, namely Facebook and Twitter. |

| 2 | This is not done in the analysis of online competition, in search of equalization or normalization patterns, as such analysis requires a full pool (or at least a wider number) of candidates or parties. |

| 3 | In Portugal, the official election campaign starts two weeks before the election day and stops the day before voters are called to the polls (that Saturday is called Dia de Reflexão, Reflection Day). However, campaigning starts quite before that, in an unofficial period dubbed pré-campanha (pre-campaign). As we focus on the two months preceding each election, the period we analyze thus encompasses the pre-campaign and the official campaign stages of the broader campaign cycle. In the analysis of professionalization, since it is not possible to anchor specific dates to expenses, we compare campaign budgets decided before the lockdown/in the pre-campaign period and actual campaign expenses. |

| 4 | Despite its name, which reflects the legacy of Portuguese revolutionary context of the early 1970s, PSD is a center-right party standing for liberal reforms in economic terms (Jalali 2007). |

| 5 | In late January, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s electoral prospects were of: 58% of support in the ICS-Iscte poll; 59.3% in the Intercampus poll; 59.7% in the Aximage poll; 61.8% in the Eurosondagem poll; 63% in the CESOP poll; and 65.4% in the Pitagórica poll. Source: ERC—Media Regulatory Entity (https://www.erc.pt/pt/sondagens/publicitacao-de-sondagens/depositos-de-2021, accessed on 17 June 2022). |

| 6 | Sources: https://www.tribunalconstitucional.pt/tc/contas_eleicoes-pr-2016.html#1104 and https://www.tribunalconstitucional.pt/tc/contas_eleicoes-pr-2021.html, accessed on 11 September 2022. |

| 7 | Except for Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa in 2021, every candidate had their own campaign website, wherein they publicized personal and campaign details, including information on specific events (e.g. Tiago Mayan Gonçalves) or the overall campaign agenda (e.g., Marisa Matias, Edgar Silva, or João Ferreira). |

| 8 | An important note on the Facebook data for Edgar Silva (Communists and Greens) and Henrique Neto (independent, former Socialist MP), both candidates in the 2016 election, is due. First, Edgar Silva did not have a public Facebook account at the time of data collection (Summer of 2022), even though we have reasons to assume that such page existed and was deleted: if we delve deeper into Edgar Silva’s Twitter, we find several references to his Facebook campaign page. Second, Henrique Neto’s official page on Facebook does not display any publications made during the two months preceding the election. Yet, there are photo albums and events that prove that his page was used for campaigning and lead us to suspect that the campaign posts have been deleted. In order to prevent the exclusion of such cases due to lack of data for Facebook, we replaced the missing data with an estimated number of Facebook contents for these candidates. These estimates were calculated via a ratio based on the social media behavior of the most similar candidate in terms of electoral result, campaign spending, traditional campaigning (presence on legacy media and on-site events), and activity (and impact) on Twitter: Vitorino Silva. Thus, we calculated Vitorino Silva’s ratio between Twitter and Facebook use, which is 1.645, and used it to compute Edgar Silva and Henrique Neto’s estimated number of posts on Facebook: that is, we multiplied their number of tweets by this ratio. For example, Henrique Neto produced 138 Tweets during the official campaign period (from January 10 to 22). This number is multiplied by 1.645, which results in an estimated value of 227 Facebook posts for Henrique Neto in such period. It is also noteworthy to underline that Cândido Ferreira has a Twitter account, but he has published no tweets during the time span covered in this study. |

| 9 | Reactions to Facebook posts aggregate “likes” and reactions such as “love”, “anger”, “sadness”, “laughter” and “surprise”. |

| 10 | We followed the procedure explained in endnote 8 to estimate Facebook engagement for Edgar Silva and Henrique Neto. |

| 11 | Other studies have used Pearson coefficients to measure the magnitude of a relationship between the properties of a limited number of units of analysis (e.g., Elmelund-Præstekær 2008). |

| 12 | Available at https://www.tribunalconstitucional.pt/tc/contas_eleicoes-pr.html#1104, accessed on 11 September 2022. |

| 13 | Gibson and Römmele (2001)’s professional campaign index includes other items that we believe are not at the core of the professionalization phenomenon, or that became obsolete or mainstream over the last 20 years and therefore are less useful in comparative research: the use of direct mail, the existence of an internal internet communication system, e-mail sign-up for news updates, external campaign headquarters, and continuous campaigning. |

| 14 | Noteworthy, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa did have an official Instagram account, but it was used under his role as President, not for his campaign. |

| 15 | The period before the lockdown comprises 51 days (from 22 November 2020, to 12 January 2021), while the period after the declaration of lockdown encompasses 10 days (from 13 January to 22 January 2021). |

References

- Bach, Laurent, Arthur Guillouzouic, and Clément Malgouyres. 2021. Does holding elections during a COVID-19 pandemic put the lives of politicians at risk? Journal of Health Economics 78: 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, Márton. 2021. Who reaps the benefits? A cross-country investigation of the absolute and relative normalization and equalization theses in the 2019 European Parliament elections. New Media & Society, 1–20, Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, Bruce, and Richard Davis. 2003. Campaigning Online: The Internet in US Elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bisbee, James, and Dan Honig. 2022. Flight to safety: COVID-induced changes in the intensity of status quo preference and voting behavior. American Political Science Review 116: 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumler, Jay G. 2016. The fourth age of political communication. Politiques de Communication 1: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, Damien, Marco Giani, André Blais, and Peter John Loewen. 2021. The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? European Journal of Political Research 60: 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, João. 2022. Portugal: From exception to the epicentre. In Governments Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Edited by Kennet Lynggaard, Mads Dagnis Jensen and Jeremy Klutch. London: Palgrave, pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa, Gowokani C., Boniface Dulani, Lonjezo Sithole, Joseph J. Chunga, Witness Alfonso, and John Tengatenga. 2022. Malawi at the crossroads: Does the fear of contracting COVID-19 affect the propensity to vote? European Journal of Development Research 34: 409–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Carlos, and Mafalda Lobo. 2015. Campanhas políticas nas redes sociais: Uma análise comparativa das eleições presidenciais em França (2012) e em Portugal (2011). In Crise Económica, Políticas de Austeridade e Representação Política. Edited by André Freire, Marco Lisi and José Manuel Leite Viegas. Lisbon: Assembleia da República, pp. 235–50. [Google Scholar]

- Data Reportal. 2021. Digital 2021: Portugal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-portugal (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Data Reportal. 2022. Digital 2022: Portugal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-portugal (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Dias, António. 2022. COVID-19 e participação eleitoral. Paper presented at the Workshop Campanhas, Partidos, Comportamentos e Geografia Eleitoral: Uma Análise das Legislativas de 2022, ICS-University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, February 4. [Google Scholar]

- Elmelund-Præstekær, Christian. 2008. Negative campaigning in a multiparty system. Representation 44: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Jorge M., and Carlos Jalali. 2017. A resurgent presidency? Portuguese semi-presidentialism and the 2016 elections. South European Society and Politics 22: 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrinho Lopes, Hugo. 2023. An unexpected socialist majority: The 2022 Portuguese general elections. West European Politics 46: 437–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrinho Lopes, Hugo, José Santana-Pereira, and Susana Rogeiro Nina. 2023. Business as usual ou novo normal? As campanhas presidenciais de 2021 em Portugal. In Da Austeridade à Pandemia: Portugal e a Europa entre as crises e as inovações. Edited by André Freire, Guya Accornero, Viriato Queiroga, Maria Asensio, Helena Belchior Rocha and José Santana-Pereira. Lisbon: Mundos Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, André, and José Santana-Pereira. 2019. The president’s dilemma: The Portuguese semi-presidential system in times of crisis (2011–2016). International Journal of Iberian Studies 32: 117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Rachel, and Andrea Römmele. 2001. Changing campaign communications: A party-centered theory of professionalized campaigning. International Journal of Press/Politics 6: 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Rachel, and Andrea Römmele. 2009. Measuring the professionalization of political campaigning. Party Politics 15: 265–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Rachel, and Ian McAllister. 2015. Normalising or equalising party competition? Assessing the impact of the web on election campaigning. Political Studies 63: 529–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giommoni, Tommaso, and Gabriel Loumeau. 2022. Lockdown and voting behaviour: A natural experiment on postponed elections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic Policy 37: 547–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grusell, Marie, and Lars Nord. 2020. Setting the trend or changing the game? Professionalization and digitalization of election campaigns in Sweden. Journal of Political Marketing 19: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, Carlos. 2007. Partidos e Democracia em Portugal, 1974–2005: Da Revolução ao Bipartidarismo. Lisbon: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- James, Toby S., and Sead Alihodzic. 2020. When is it democratic to postpone an election? Elections during natural disasters, COVID-19, and emergency situations. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 19: 344–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc-Michalska, Karolina, Darren G. Lilleker, Alison Smith, and Daniel Weissmann. 2016. The normalization of online campaigning in the Web 2.0 era. European Journal of Communication 31: 331–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, Arndt, and Max Schaub. 2020. Voting at the dawn of a global pandemic. Working Paper, SocArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-On, Azi, and Sharon Haleva-Amir. 2018. Normalizing or equalizing? Characterizing Facebook campaigning. New Media & Society 20: 720–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lilleker, Darren G., and Ralph Negrine. 2002. Professionalization: Of what? Since when? By whom? International Journal of Press/Politics 7: 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, Marco. 2013. The professionalization of campaigns in recent democracies: The Portuguese case. European Journal of Communication 28: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, Marco, and José Santana-Pereira. 2015. Personalização das campanhas em eleições legislativas: O contexto importa? Campanhas antes e depois da Troica (2009–2011). In Crise Económica, Políticas de Austeridade e Representação Política. Edited by André Freire, Marco Lisi and José Manuel Leite Viegas. Lisbon: Assembleia da República, pp. 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Luís, Carla. 2021. Presidential Elections in Portugal: From ‘Restrictions as Usual’ to Unexpected Lockdown. Country Report. Stockholm: International IDEA. Available online: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/2021-09-24-case-study-presidential-elections-in-portugal-from-restrictions-as-usual-to-unexpected-lockdown-en.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Magalhães, Pedro C., John H. Aldrich, and Rachel K. Gibson. 2020. New forms of mobilization, new people mobilized? Evidence from the comparative study of electoral systems. Party Politics 26: 605–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Michael, and David Resnick. 2000. Politics as Usual: The Cyberspace “Revolution”. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Morisi, Davide, Héloïse Cloléry, Guillaume Kon Kam King, and Max Schaub. 2021. How COVID-19 Affects Voting for Incumbents: Evidence from Local Elections in France. Working Paper, OSF Preprints, Charlottesville (USA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykkänen, Juri, Lars Nord, and Tom Moring. 2021. Ten years after: Is the party-centered theory of campaign professionalization still valid? Party Politics 28: 1176–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, Octavio A., and Marina Costa Lobo. 2009. Portugal’s semi-presidentialism (re) considered: An assessment of the president’s role in the policy process, 1976–2006. European Journal of Political Research 48: 234–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa. 2000. A Virtuous Circle: Political Communications in Postindustrial Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrá, Daniela. 2021. Professionalization of political campaigns: Roadmap for the analysis. Slovak Journal of Political Sciences 21: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchio, Matteo, and Raffaella Santolini. 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on voter turnout. European Journal of Political Economy 73: 102161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, Sara. 2018. O uso da internet pelos políticos em campanhas eleitorais: Portugal legislativas 2015. Doctoral dissertation, Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski, Adam, and Henry Teune. 1970. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, Hannah, Edouard Mathieu, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Joe Hasell, Bobbie MacDonald, Diana Beltekian, Saloni Dattani, and et al. 2021. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). In Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Sampugnaro, Rossana, and Francesca Montemagno. 2021. In search of the americanization: Candidates and political campaigns in European general election. Journal of Political Marketing 20: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel-Azran, Tal, Moran Yarchi, and Gadi Wolfsfeld. 2015. Equalization versus normalization: Facebook and the 2013 Israeli elections. Social Media + Society 1: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, Andrés, José Rama, and Fernando Casal Bertoa. 2020. The Coronavirus pandemic and voter turnout: Addressing the impact of COVID-19 on electoral participation. Working Paper, SocArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Pereira, José. 2022. Election campaigns. In Oxford Handbook of Portuguese Politics. Edited by Jorge M. Fernandes, Pedro C. Magalhães and António Costa Pinto. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 262–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Beck, Rüdiger, and David M. Farrell. 2002. Do political campaigns Matter? Campaign Effects in Elections and Referendums. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Seiceira, Filipa, and Carlos Cunha. 2015. Campanhas eleitorais online: Uma análise comparada. In Crise Económica, Políticas de Austeridade e Representação Política. Edited by André Freire, Marco Lisi and José Manuel Leite Viegas. Lisbon: Assembleia da República, pp. 201–20. [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Silva, Sofia, and Nelson Santos. 2022. The 2021 portuguese presidential elections under extraordinary circumstances: COVID-19 and the rise of the radical right in Portugal. Mediterranean Politics, 1–11, Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Patrícia, Edna Costa, and JoãO Moniz. 2021. A Portuguese miracle: The politics of the first phase of COVID-19 in Portugal. South European Society and Politics, 1–29, Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, Antonio. 2020. Managing Elections under the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Republic of Korea’s Crucial Test. International IDEA Technical Paper 2/2020. Stockholm: International IDEA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, Kim. 2008. Online electoral competition in different settings: A comparative meta-analysis of the research on party websites and online electoral competition. Party Politics 14: 223–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, Jesper. 2007. Political marketing and professionalized campaigning. Journal of Political Marketing 6: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Kate. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on the 2020 US Presidential Election. Case Study. Stockholm: International IDEA. Available online: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/multimedia_reports/impact-of-covid19-on-the-2020-us-presidential-lections-en.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Tenscher, Jens. 2013. First-and second-order campaigning: Evidence from Germany. European Journal of Communication 28: 241–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenscher, Jens, Juri Mykkänen, and Tom Moring. 2012. Modes of professional campaigning: A four-country comparison in the European parliamentary elections, 2009. The International Journal of Press/Politics 17: 145–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, Maurice, Liesbeth Hermans, and Steven Sams. 2013. Online social networks and micro-blogging in political campaigning: The exploration of a new campaign tool and new campaign style. Party Politics 19: 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtosu, Ina I. 2021. How COVID-19 changed ‘the anatomy’ of political campaigning. In Central and Eastern European eDem and eGov Days. Edited by Thomas Hemker, Robert Müller-Török, Alexander Prosser, Péter Sasvári, Dona Scola and Nicolae Urs. Conference Proceedings (no. 346). Austria: Facultas Verlags-und Buchhandels AG, pp. 351–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Jung, and Young Mie Kim. 2017. Equalization or normalization? Voter–candidate engagement on Twitter in the 2010 US midterm elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14: 232–47. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santana-Pereira, J.; Ferrinho Lopes, H.; Nina, S.R. Sailing Uncharted Waters with Old Boats? COVID-19 and the Digitalization and Professionalization of Presidential Campaigns in Portugal. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010045

Santana-Pereira J, Ferrinho Lopes H, Nina SR. Sailing Uncharted Waters with Old Boats? COVID-19 and the Digitalization and Professionalization of Presidential Campaigns in Portugal. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantana-Pereira, José, Hugo Ferrinho Lopes, and Susana Rogeiro Nina. 2023. "Sailing Uncharted Waters with Old Boats? COVID-19 and the Digitalization and Professionalization of Presidential Campaigns in Portugal" Social Sciences 12, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010045

APA StyleSantana-Pereira, J., Ferrinho Lopes, H., & Nina, S. R. (2023). Sailing Uncharted Waters with Old Boats? COVID-19 and the Digitalization and Professionalization of Presidential Campaigns in Portugal. Social Sciences, 12(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010045