Uncovering Youth’s Invisible Labor: Children’s Roles, Care Work, and Familial Obligations in Latino/a Immigrant Families

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The New Sociology of Childhood and Migrant Youth

3. Care Work in Immigrant Families

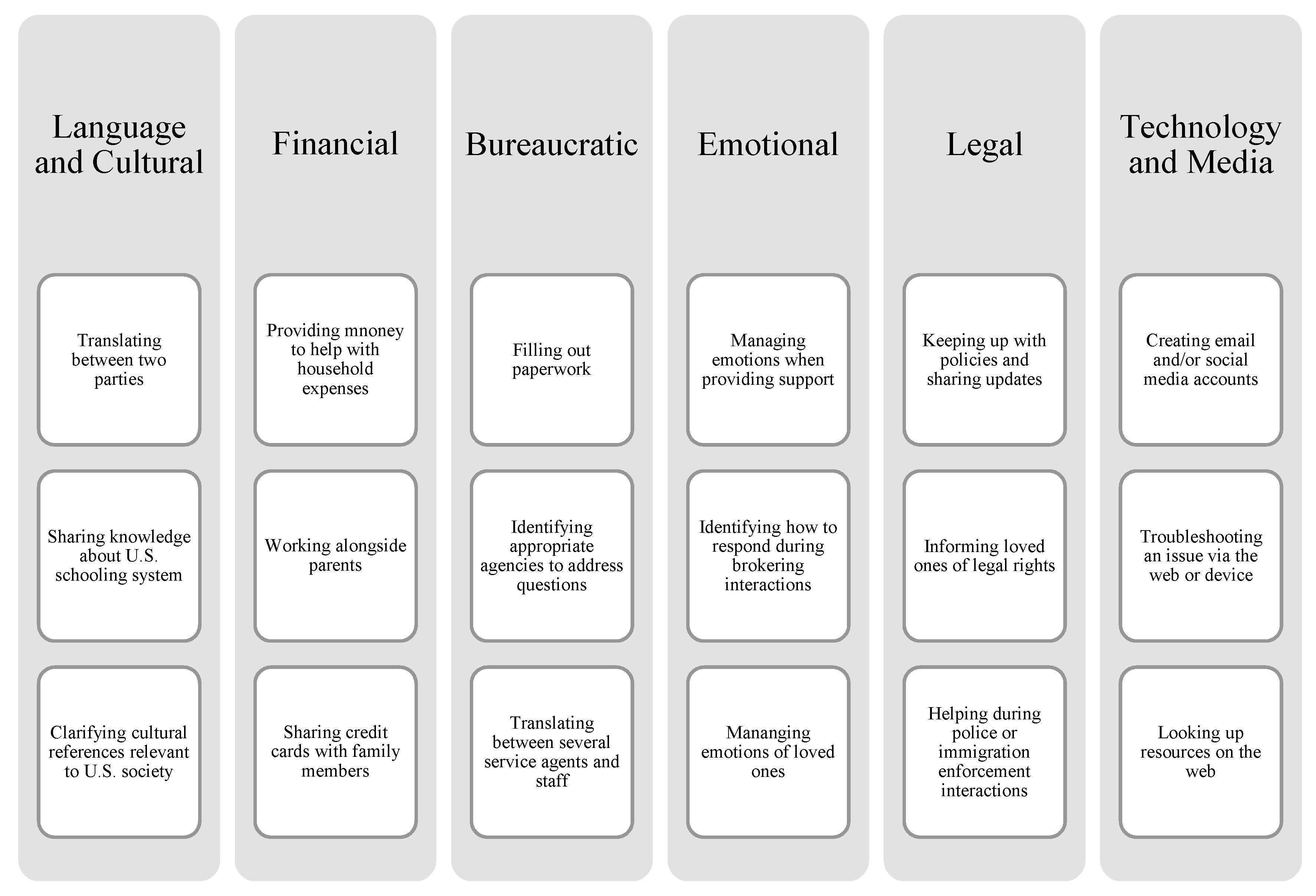

4. Dimensions of Youth Care Work in Immigrant Families

4.1. Language and Cultural Support

4.2. Financial Support

4.3. Bureaucratic Support

4.4. Emotional Support

4.5. Legal Support

4.6. Technology Support

5. Directions for Future Research

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | There is research on immigrants in care work professions. This essay draws attention to care work research within the family unit. |

| 2 | The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision on the legality of the DACA program on 5 October 2022. Current DACA recipients are able to continue their benefits and renew their work authorization. However, first-time applications will not be processed at this time (National Immigration Law Center 2022). |

References

- Abrego, Leisy J. 2016. Illegality as a source of solidarity and tension in Latino families. Journal of Latino/Latin American Studies 8: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, Leisy J. 2018. Renewed optimism and spatial mobility: Legal consciousness of Latino Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipients and their families in Los Angeles. Ethnicities 18: 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, Leisy J. 2019. Relational Legal Consciousness of U.S. Citizenship: Privilege, Responsibility, Guild and Love in Latino Mixed-Status Families. Law & Society Review 53: 641–70. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, Elizabeth, Elizabeth Vaquera, and Heide Castañeda. 2021. Shifting roles in families of deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA) recipients and implications for the transition to adulthood. Journal of Family Issues 42: 2111–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, John. 1992. Childhood gender roles: Social context and organisation. In Childhood Social Development. London: Psychology Press, pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, Asad L. 2020. On the Radar: System embeddedness and Latin American immigrants’ perceived risk of deportation. Law & Society Review 54: 133–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, Frank D., Susan K. Brown, James D. Bachmeier, Susan Brown, and James Bachmeier. 2015. Parents Without Papers: The Progress and Pitfalls of Mexican American Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Borrero, Noah. 2011. Nurturing students’ strengths: The impact of a school-based student interpreter program on Latino/a students’ reading comprehension and English language development. Urban Education 46: 663–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, Sarah, and Gabrielle Oliveira. 2022. Multidirectional carework across borders: Latina immigrant women negotiating motherhood and daughterhood. Journal of Marriage and Family 84: 691–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriel, Raymond, Julia A. Love, and Terri L. De Ment. 2006. The Relation of Language Brokering to Depression and Parent-Child Bonding Among Latino Adolescents. In Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships: Measurement and Development. Edited by Marc H. Bornstein and Linda R. Cote. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 249–70. [Google Scholar]

- Buriel, Raymond, William Perez, Terri L. De Ment, David V. Chavez, and Virginia R. Moran. 1998. The relationship of language brokering to academic performance, biculturalism, and self-efficacy among Latino adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 20: 283–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizales, Stephanie L. 2021. Work Primacy and the Social Incorporation of Unaccompanied, Undocumented Latinx Youth in the United States. Social Forces. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizales, Stephanie L. 2022. “Si Mis Papas Estuvieran Aquí”: Unaccompanied Youth Workers’ Emergent Frame of Reference and Health in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizales, Stephanie L., and Jody Agius Vallejo. 2021. Latinos & racism in the Trump era. Daedalus 150: 150–64. [Google Scholar]

- Canizales, Stephanie L., and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2022. Working-class Latina/o youth navigating stratification and inequality: A review of literature. Sociology Compass. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capps, Randy, Michael Fix, Julie Murray, Jason Ost, Jeffrey S. Passel, and Shinta Herwantoro. 2005. The new demography of America’s schools: Immigration and the No Child Left Behind Act. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Pia, and Allison James. 2000. Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices. New York: The Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Pia Haudrup. 2004. Children’s Participation in Ethnographic Research: Issues of Power and Representation. Childhood and Society 18: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Pia, and Alan Prout. 2002. Working with Ethical Symmetry in Social Research with Children. Childhood 9: 477–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Wyatt, Kimberly Turner, and Lina Guzman. 2017. One Quarter of Hispanic Children in the United States Have an Unauthorized Immigrant Parent. Bethesda: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Available online: https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Hispanic-Center-Undocumented-Brief-FINAL-V21.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Comunidades Indigenas en Liderazgo (CIELO). 2022. Indigenous Languages. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/618560a29f2a402faa2f5dd9ded0cc65 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Corsaro, William. 2005. The Sociology of Childhood. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crafter, Sarah, and Humera Iqbal. 2022. Child language brokering as a family care practice: Reframing the ‘parentified child’ debate. Children & Society 36: 400–14. [Google Scholar]

- Davin, Anna. 1996. Growing Up Poor: Home, School and Street in London 1870–1914. London: Rivers Oram Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, John M. 1998. Understanding the Meanings of Children: A Reflexive Process. Childhood and Society 12: 325–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Vanessa. 2020a. Children of immigrants as “brokers” in an era of exclusion. Sociology Compass 14: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Vanessa. 2020b. “They think I’m a lawyer”: Undocumented college students as legal brokers for their undocumented parents. Law & Policy 42: 261–83. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Vanessa. 2020c. Decoding the hidden curriculum: Latino/a first-generation college students’ influence on younger siblings’ educational trajectory. Journal of Latinos and Education, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Vanessa. 2022a. Family formation under the law: How immigration laws construct contemporary Latino/a immigrant families in the US. Sociology Compass 16: e13027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Vanessa. 2022b. Leveraging protections, navigating punishments: How adult children of undocumented immigrants mediate illegality in Latinx families. Journal of Marriage and Family 84: 1427–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Vanessa. 2022c. Opinion: Even During the Surge, Hospitals Must Ensure immigrant Patients Have Family Sup-port. California Health Report. Available online: https://www.calhealthreport.org/2022/01/25/opinion-even-during-the-surge-hospitals-must-ensure-immigrant-patients-have-family-support/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Delgado, Vanessa. n.d. “From in-between” to “front and center”: How Brokering Shifts to Advocacy in Emerging Adulthood. Unpublished book chapter.

- Desai, Sarah, Jessica Houston Su, and Robert M. Adelman. 2020. Legacies of Marginalization: System Avoidance among the Adult Children of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States. International Migration Review 54: 707–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreby, Joanna. 2015. Everyday Illegal: When Policies Undermine Immigrant Families. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- England, Paula, Michelle Budig, and Nancy Folbre. 2002. Wages of virtue: The relative pay of care work. Social Problems 49: 455–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Rebecca, Jamilia Blake, and Thalia González. 2017. Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood. Washington, DC: Center on Poverty and Inequality at Georgetown Law. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, Emir. 2016. Economic empathy in family entrepreneurship: Mexican-origin street vendor children and their parents. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 1657–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, Emir. 2019. Kids at Work: Latinx Families Selling Food on the Streets of Los Angeles. New York: New York University Press, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Gary, and Kent Sandstrom. 1988. Knowing Children: Participant Observation with Minors. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Andrea. 2021. The Succeeders: How Immigrant Youth Are Transforming What It Means to Belong in America. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni, Andrew, and Sara Pedersen. 2002. Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology 38: 856–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Valdivia, Isabel. 2022. Legal power in action: How latinx adult children mitigate the effects of parents’ legal status through brokering. Social Problems 69: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getrich, Christina. 2019. Border Brokers: Children of Mexican Immigrants Navigating U.S. Society, Laws, and Politics. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel, Naomi. 2000. The third shift: Gender and care work outside the home. Qualitative Sociology 23: 467–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Roberto G., Sayil Camacho, Kristina Brant, and Carlos Aguilar. 2019. The Long-Term Impact of DACA: Forging Futures Despite DACA’s Uncertainty. Cambridge: National UnDACAmented Research Project. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Sheila, and Diane Hogan. 2005. Researching Children’s Experience. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryeva, Angelina. 2017. Own gender, sibling’s gender, parent’s gender: The division of elderly parent care among adult children. American Sociological Review 82: 116–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Limin. 2017. Using school websites for home–school communication and parental involvement? Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 3: 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Shu-Sha Angie, Afaf Nash, and Marjorie Faulstich Orellana. 2016. Cultural and social processes of language brokering among Arab, Asian, and Latin immigrants. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37: 150–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbrink, Lauren. 2018. Circulation of care among unaccompanied migrant youth from Guatemala. Children and Youth Services Review 92: 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2015. The managed heart. In Working in America. New York: Routledge, pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. 2012. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth, Sumi, Ayo Mansaray, Kim Allen, and Anthea Rose. 2011. Parents’ perspectives on technology and children’s learning in the home: Social class and the role of the habitus. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 27: 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette, and Ernestine Avila. 1997. “I’m here, but I’m there” the meanings of Latina transnational motherhood. Gender & Society 11: 548–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Suzanne, Berry Mayall, and Sandy Oliver. 1999. Critical Issues in Social Research: Power and Prejudice. Philadelphia: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- James, Allison, Chris Jenks, and Alan Prout. 1998. Theorizing Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- James, Allison. 2017. Constructing Childhood: Theory, Policy and Social Practice. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Curtis J., and Edison J. Trickett. 2005. Immigrant adolescents behaving as culture brokers: A study of families from the former Soviet Union. The Journal of Social Psychology 145: 405–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, Jennifer A., and Vanja Lazarevic. 2014. Communicating for One’s Family: An Interdisciplinary Review of Language and Cultural Brokering in Immigrant Families. Annals of the International Communication Association 38: 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Vikki S. 2010. How children of immigrants use media to connect their families to the community: The case of Latinos in South Los Angeles. Journal of Children and Media 4: 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Vikki S. 2014. Kids in the Middle: How Children of Immigrants Negotiate Community Interactions for Their Families. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Stan J. 1999. Facing the Child: Rethinking Models of Agency in Parent-child Relations. Contemporary Perspectives on Family Research 1: 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Hyeyoung. 2014. The hidden injury of class in Korean-American language brokers’ lives. Childhood 21: 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanuza, Yader R. 2020. Giving (Money) Back To Parents: Racial/Ethnic and Immigrant–Native Variation in Monetary Exchanges During the Transition to Adulthood. Sociological Forum 35: 1157–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Amanda E. 2003. Race in the Schoolyard: Negotiating the Color Line in Classrooms and Communities. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, Beatriz, Krista E. Garver, Trinity A. Urban, Nicole A. Lazar, and John A. Sweeney. 2004. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Development 75: 1357–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, Mark. 2016. Trends and Challenges Facing America’s Latino Children. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. Available online: https://www.prb.org/resources/trends-and-challenges-facing-americas-latino-children/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Matthews, Sarah H. 2007. A window on the ‘new’ sociology of childhood. Sociology Compass 1: 322–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Leisy Abrego. 2012. Legal violence: Immigration law and the lives of Central American immigrants. American Journal of Sociology 117: 1380–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, Alejandro, Oksana F. Yakushko, and Antonio J. Castro. 2012. Language Brokering Among Mexican-Immigrant Families in the Midwest: A Multiple Case Study. The Counseling Psychologist 40: 520–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Immigration Law Center. 2022. DACA. Available online: https://www.nilc.org/issues/daca/#:~:text=On%20October%2031%2C%202022%2C%20the,remains%20available%20for%20DACA%20holders (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Negrón-Gonzales, Genevieve. 2014. Undocumented, unafraid and unapologetic: Re-articulatory practices and migrant youth “illegality”. Latino Studies 12: 259–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, Kate, and Gerda Kumpiene. 2014. Language brokering and self-concept: An exploratory study of Latino students’ experiences in middle and high school. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 36: 124–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, Christine. 2013. Using technology to increase parent involvement in schools. TechTrends 57: 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, Marjorie Faulstich. 2009. Translating Childhoods: Immigrant Youth, Language, and Culture. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, Marjorie Faulstich. 2019. Mindful Ethnography: Mind, Heart and Activity for Transformative Social Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, Marjorie Faulstich, Lisa Dorner, and Lucila Pulido. 2003. Accessing assets: Immigrant youth’s work as family translators or para-phrasers. Social Problems 50: 505–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patler, Caitlin, Erin Hamilton, Kelsey Meagher, and Robin Savinar. 2019. Uncertainty about DACA may undermine its positive impact on health for recipients and their children. Health Affairs 38: 738–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patler, Caitlin, Erin R. Hamilton, and Robin L. Savinar. 2021a. The limits of gaining rights while remaining marginalized: The deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA) program and the psychological wellbeing of Latina/o undocumented youth. Social Forces 100: 246–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patler, Caitlin, Jo Mhairi Hale, and Erin Hamilton. 2021b. Paths to mobility: A longitudinal evaluation of earnings among Latino/a DACA recipients in California. American Behavioral Scientist 65: 1146–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrikakou, Eva N. 2016. Parent Involvement, Technology, and Media: Now What? School Community Journal 26: 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Prout, Alan. 2005. The Future of Childhood: Towards the Interdisciplinary Study of Children. New York: Routledge/Falmer. [Google Scholar]

- Prout, Alan. 2011. Taking a Step Away from Modernity: Reconsidering the New Sociology of Childhood. Global Studies of Childhood 1: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Jennifer F., and Marjorie Faulstich Orellana. 2009. New immigrant youth interpreting in white public space. American Anthropologist 111: 211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, Victoria, and Vikki S. Katz. 2016. Opportunity for All? Technology and Learning in Lower-Income Families. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, Rubén G., and Golnaz Komaie. 2010. Immigration and adult transitions. The Future of Children 20: 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzbauer, Leah, and Manuel Rodriguez. 2022. Pathways to Mobility: Family and Education in the Lives of Latinx Youth. Qualitative Sociology, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzbauer, Leah. 2004. Searching for wages and mothering from afar: The case of Honduran transnational families. Journal of Marriage and Family 66: 1317–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Lucy. 1995. Language brokering among Latino adolescents: Prevalence, attitudes, and school performance. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 17: 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Lucy. 1996. Language brokering in linguistic minority communities: The case of Chinese-and Vietnamese-American students. Bilingual Research Journal 20: 485–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2014. Expanding Definitions of Giftedness: The Case of Young Interpreters from Immigrant Communities. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, Abel, Jr. 1999. Gender roles and settlement activities among children and their immigrant families. American Behavioral Scientist 42: 720–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, Jody Agius. 2012. Barrios to Burbs: The Making of the Mexican American Middle Class. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Jody Agius, and Jennifer Lee. 2009. Brown picket fences: The immigrant narrative and ‘giving back’ among the Mexican-origin middle class. Ethnicities 9: 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, Edward D., and Maureen A. Pirog. 2016. Mixed-status families and WIC uptake: The effects of risk of deportation on program use. Social Science Quarterly 97: 555–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisskirch, Robert S. 2010. Child language brokers in immigrant families: An overview of family dynamics. mediAzioni 10: 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Tom, Greisa Martinez Rosas, Adam Luna, Henry Manninig, Adrian Reyna, Patrick O’Shea, Tom Jawetz, and Philip E. Wolgin. 2017. DACA Recipients’ Economic and Educational Gains Continue to Grow. Center for American Progress. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/daca-recipients-economic-educational-gains-continue-grow/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Yoshikawa, Hirokazu. 2011. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, Viviana A. 1994. Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delgado, V. Uncovering Youth’s Invisible Labor: Children’s Roles, Care Work, and Familial Obligations in Latino/a Immigrant Families. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010036

Delgado V. Uncovering Youth’s Invisible Labor: Children’s Roles, Care Work, and Familial Obligations in Latino/a Immigrant Families. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelgado, Vanessa. 2023. "Uncovering Youth’s Invisible Labor: Children’s Roles, Care Work, and Familial Obligations in Latino/a Immigrant Families" Social Sciences 12, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010036

APA StyleDelgado, V. (2023). Uncovering Youth’s Invisible Labor: Children’s Roles, Care Work, and Familial Obligations in Latino/a Immigrant Families. Social Sciences, 12(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010036