2. State of the Art

The analysis of the recent mutations of the processes of co-construction and socio-territorial deconstruction in a multicultural region, with cross-border traditions and vocation, appeals to a series of concepts debated in the literature. To substantiate this article, we used mainly the concepts of ethnic minority, co-construction and socio-territorial deconstruction, cross-border space and interculturality, which we consider indispensable for understanding the social transformations in Timiș County, for the last 30 years.

The concept of minority ethnic community is defined by bringing together other major concepts: ethnic group, ethnic minority, and community. The first of these refers to a group of people differentiated from the rest of the community by their racial origin or cultural background (

Sollors 2001, pp. 4813–17). An ethnic minority is an ethnic group less numerous than the majority ethnic group in a country. The concept of community has among its defining features a feeling of belonging, social cohesion, mechanisms of self-preservation, and territory (

Aitken 2009, pp. 221–25). These are also the basis for the processes of co-construction and territorial deconstruction.

Corroborating the definitions given by geographers (

Costachie 2004;

Smith 2020) and sociologists (

Barth 1969;

Rex 1998), We can deduce some specific features of the ethnic minorit, with an operational role in carrying out this work:

- -

The ethnic minority lives on the same political territory as the majority population.

- -

It is less numerous than the majority population.

- -

It has cultural features that differentiate it: language, religion, material culture.

- -

It has a set of immaterial cultural elements that compose its subjective ethos.

- -

It has a mutual perception of otherness from the majority population and from other populations that are differentiated by the cultural elements listed above.

The origins of the ethnic groups in Timiș County, part of the historical region of Banat, are in the process of colonization initiated by the Habsburgs in the 18th century. After the expulsion of the Turks in 1716 and the conclusion of the Passarowitz Peace in 1718, the Habsburgs repopulated the parts of Banat affected by the long wars, especially the lowlands of Timiș County. Preference was given to colonizations with Catholic populations—especially Germans—from different regions of the vast empire (

Kahl and Jordan 2004;

Crețan et al. 2008), but also from outside the empire, such as the Catholic Bulgarians, since 1732 (

Muntean 1990;

Crețan 1999), even groups of Orthodox (Serbs), previously asserted in their revolts and struggles with the Turks and persecuted in the Ottoman Empire (

Cerović 2005). The colonization of all these groups took place in waves, during the 18th century (

Crețan 1999), so that in the 19th century the Hungarian communities were also consolidated, as a result of the increasing influence of Budapest in the administration of the region (

Berecz 2021).

Norwegian sociologist Fredrick Barth believes that an ethnic group is defined by the border it builds in relation to other ethnic groups, rather than by its whole cultural heritage (

Barth 1969). However, studies have shown that, in Banat, the boundaries between groups and communities were not hermetic, but favored co-construction and the interculturality (

Neumann 1997,

2012;

Leu 2007).

Co-construction is a concept that belongs to the postmodern way of thinking. Having initially been used to explain the part played by language in the construction of the shared language and ideology of groups, it was subsequently applied to other areas within socio-human research, such as the construction of identities and of social institutions. When people carry out activities in common, the co-participants become co-authors, irrespective of the role they play. Through their co-participation, people manage to take ownership of the performing and the result of the activity. This is an opportunity for axiologies, behaviours and identities to be constructed. A further consequence of co-construction is the sense of otherness, along with stereotypes (

Jacoby and Ochs 1995). Constructed in the course of the negotiating process, these become foundations for group identity co-construction. Furthermore, “this notion of co-construction, of together carrying out our interactions with the others, lies at the basis of any intercultural encounter” (

https://en.unesco.org/interculturaldialogue/core-concepts, accessed on 25 March 2021).

In Banat, the practice of intercultural exchanges within the region and cross-border cultural exchanges marked the personality of this historical region. In the context of European integration, there are processes of deconstruction—conceptual reconstruction of the territory, which have multiple implications in the relationship of minority ethnic groups with the host country and the related country.

Territorial deconstruction, as a poststructuralist approach, is based on the role of the experience of human groups in the historical development of place and region (

Paasi 1991). Both a region and its boundaries are established in territory by means of political institutions. In the social imaginary, these concepts are far more fluid, since they constitute, at the same time, socio-cultural constructs that are the results of the process of intercultural negotiation. Subjective space and semioticised space do not always fit precisely on to the region or its limits (

Gottmann 1973). Groups relate to the objective constructs of territory (the region and its boundaries) in ways that are conditioned by their historical and cultural experience (

Painter 2010).

Observation of the social perception of territory and of socio-cultural practices shows up differences between reality as institutionally objectivised (with its territorial subdivisions) and the constructed reality of groups—particularly the cultural reinterpretation of territory and its boundaries. This is fed by any differences that exist between social reality and the politico-administrative status of the territory concerned. Studies published in the last few decades highlight differences of this kind, especially in cross-border spaces in which intercultural negotiation and regional feeling are very active (

Newman and Paasi 1998;

Paasi 1999;

Paasi 2003a,

2003b;

Perkmann 2003;

Painter 2010;

Hlihor 2011), while institutionally established territorial limits are criticised in the practice of social and economic relations (

Balibar 2009;

Decoville and Durand 2019).

The phenomenon becomes even more complex when we look at old historic regions that are fragmented by national borders, as is frequently the case in Central and Eastern Europe (e.g., Bucovina, Silesia, Tyrol). The presence of ethnic minorities whose origins lie in the neighbouring nation states accentuates the difference between the objective, institutional aspects of territorial construction and the fluid reality of social constructs, calling into question regional boundaries as currently established (

Andreescu and Bardaș 2016). Banat is a region of this kind; it existed for centuries on the southern edge of first the Habsburg and then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, before becoming a cross-border region, divided up in 1919 between Romania, Serbia and Hungary.

In the context of the European integration process, the borders between the nation states established in the last century are becoming more flexible, and their functions increasingly depend on the regional decision-maker, to the detriment of the national central one. This is an opportunity for the development and assertion of municipal and county authorities in control of their own territory (

Castañeda 2020).

Cross-border space is a term accepted by geographers as referring to an area extending to a depth of 30–60 km into the territory of two neighbouring countries on both sides of the national border. Its extent can be reduced or extended as the strength of cross-border ties changes (

Săgeată 2014).

Free circulation, the democratisation of access to information, and changes in the epistemology of the socio-human sciences have generated constructivist-type debates regarding frontiers (

Hlihor 2011;

Smith 2020;

Săgeată 2020). A frontier is no longer a limit but rather a multi-layered meeting zone between sovereignties, economies and people, a distinct and polymorphous space in which different subsystems interact and interpenetrate (

Balibar 2009;

Burridge et al. 2017).

The poststructuralist approach to cross-border spaces foregrounds the theme of territorial deconstruction, necessitated by the new socio-political context. In western Romania, territorial deconstruction highlights reactions to the “closing in” of the Cold War era. Here, the border drawn in 1919 cut through old functional geographical spaces such as Banat, Crișana (Partium) and Maramureș, in which the elements of difference in discourses regarding territoriality and the limits of territory are many in number: the liberalisation of cross-border circulation, the activation of cross-border social networks (

Brubaker 1999), regional identity, and interculturalism.

As a social phenomenon,

interculturality has been defined in a variety of ways in different contexts and on the basis of different premises.

Meer and Modood (

2012) focused on dialogue between the majority and minority populations.

Levey (

2012) tended, rather, to emphasise dialogue between human groups who bear different cultural distinctives.

The essence of interculturality lies in the process of social negotiation (

Cantle 2012). If multiculturalism means mutual toleration, interculturalism corresponds to a higher level of dialogue between groups. The essential condition here is reciprocal recognition of distinct features, followed by intercultural exchange “as an experience of individual transformation with possibilities that are relational and repeatable in larger networks” (

McIvor 2019, p. 345). Of course, this means not hybridisation but the reciprocal enriching of those who take part in the negotiating process through “their entering into resonance” on the basis of a shared purpose (

Buzărnescu et al. 2004).

There is no doubt that negotiation and the exchange of cultural values also imply renunciation. What is essential is a recognition of the limitations of one’s own axiology and an orientation towards the search for norms both sides can accept (

Hofstede 2001) the adoption of behaviours of accommodation, for opportunistic reasons (

Camilleri et al. 1990). In Banat, the settling of colonists of different ethnic origins (sometimes even of groups who held antagonistic positions in their areas of origin) was followed by a process of adaptation and acculturation without losing ethnic identity (

Neumann 1997). The colonists developed a feeling of regional belonging and adopted a shared axiological system in which a sense of property and material values are extremely important. Some studies have treated pragmatism and opportunism as features specific to the population of Banat, the consequence of a process of social learning (

Adam 2008).

Recent studies, conducted in the context of intercultural communication, also indicate that the direct contact of individuals of different ethnicities reduces the incidence of their prejudices and the perception of otherness. This process is facilitated by equal status, the existence of common goals and the support of the authorities (

Imperato et al. 2021).

It is beyond doubt that the Germans and Hungarians constituted the social elite, because of the positions they held in the apparatus of government, but interethnic cooperation on a wider scale was encouraged. The Empire needed peace on its borders, and Banat was a frontier province that was exposed to powerful external pressures (

Neumann 2012).

Taking into consideration the arguments identified in documentary sources, it is clear that the region we are studying displays intercultural co-construction that is deeply rooted in history. It was on the basis of this background that, after 1990, both deconstruction and the present-day intercultural social co-construction took place and are taking place. Politically speaking, the motive force for this was the process of European integration. In the course of this process, the border underwent a process of functional change. Whereas during the communist period the national frontier had played the role of a barrier, from 1990 onwards it increasingly served as a zone of meeting and exchange between Banat people of different ethnicities living in the three neighbouring countries of Romania, Serbia and Hungary. The founding in 1997 of the DKMT Euroregion, followed in 2007 by Romania’s entry into the EU, stimulated these processes and provided institutional and functional leverage to promote cultural identities and increase the resilience of local ethnic minorities (

Săgeată 2014).

The concept of

resilience is an important concern of social and geographical studies. Synthetically, it includes a number of concepts: individual and group capacity to respond to local needs and issues, community networks, people-place connections, community infrastructure, diverse and innovative economy, engaged governance in regional decision making (

Maclean et al. 2014).

Sustainability is inextricably linked to the concepts of development and resilience. It refers to the ability of today’s communities to grow without jeopardizing future generations’ security and access to resources.

Social sustainability and social resilience are interlinked. The first relies on safety and equity as key concepts (

Eizenberg and Jabareen 2017). This article highlights, on the one hand, the resilience of the model of intercultural coexistence in the studied cross-border area and, on the other hand, the implications and sustainability of this phenomenon in the process of territorial deconstruction in the wider context of Romania’s European integration.

After 1990, a series of

scientific papers on the studied region were published on the subject of this study. Territoriality and the production of space were treated especially after 2000 (

Popa 2006;

Ancuța 2008;

Săgeată 2014;

Anderson 2020). In this context, an important role was played by the historical heritage from the 18th to 19th centuries, when this territory was colonized by the Habsburgs and the ethnic mosaic was created (

Kahl and Jordan 2004;

Anderson 2020). Today, European integration and the constitution of the DKMT Euroregion have an important role in the deconstruction of territoriality and in the production of space (

Popa 2006;

Săgeată 2014). Cross-border relations and cross-border space have been more in the attention of geographers and geopoliticians (

Hlihor 2011). The regional identity in Banat has been the subject of numerous sociological studies (

Gavreliuc 2003;

Buzărnescu et al. 2004;

Pascaru 2005), anthropological (

Adam 2008;

Babeți 2008), historical (

Neumann 2012;

Constantin and Lungu-Badea 2014), geographical (

Voiculescu 2005;

Crețan et al. 2008). Studies on ethnic identity (

Crețan et al. 2008;

Gidó 2012,

2013), ethnic minorities (

Crețan 1999) and interethnic relations (

Andreescu 2004;

Buzărnescu et al. 2004;

Kahl and Jordan 2004;

Crețan et al. 2008;

Micle 2013;

Gidó 2012,

2013;

Berecz 2021) reveals a winding path to the development of a resilient interethnic cultural complex, specific to this region (

Adam 2008;

Neumann 2012;

Micle 2013).

In this context, our contribution to knowledge in the field results from the corroboration of previous research, with the results of socio-geographical research undertaken by us, in an integrated perspective. Within it, the emphasis is on the cross-border dimensions of the relations of the Hungarian, Serbian and Ukrainian ethnic minorities in Timiș County and on the role of those relations in the recent processes of transformation, through co-construction and socio-territorial deconstruction.

4. Results

The analysis of official statistical data highlighted contrasting trends in the last 3 decades. During the deep crisis of the 1990s, the population of Timiș County decreased from 700,033 inhabitants in 1992 to 677,926 inhabitants in 2002, due to the majority of ethnic groups, including Romanians, but especially by completing the massive emigration of ethnic Germans. As a result, the share of minorities in the total population of the county decreased from 19.86% to 16.54%. In the 2000s, the population tended to stabilize, so that at the last census (2011), in Timiș County there were 683,540 inhabitants, of which only 634,150 declared their ethnicity; of these, 13.14% belonged to ethnic minorities, marking a decrease following Romania’s integration into the EU, which facilitated emigration. Subsequently, the population of the county had a slight growth trend, the regional authorities estimating a resident population of 705,500 inhabitants, on 1 January 2021. In the studied region, 97.3% of localities were inhabited not only by Romanians but also by at least three people of another ethnicity (

Database of the Regional Bureau of Statistics Timișoara 2021).

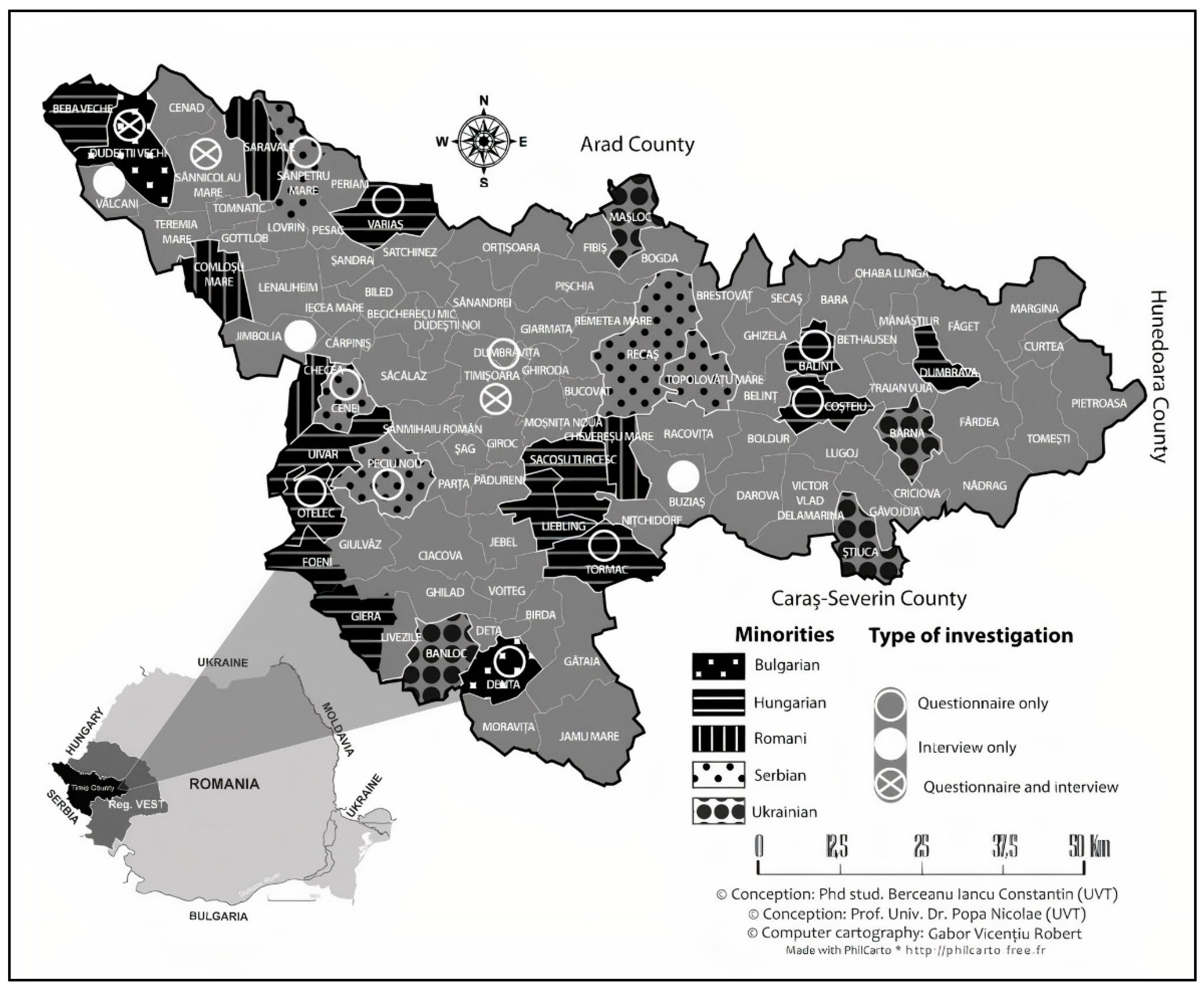

However, although the inhabitants belonging to different ethnic minorities are spread throughout the territory of Timiș County, their dispersion and territorial concentration are not uniform. A small part of the localities inhabited by them fall into the category of ethnic minority communities (with representative concentrations), which belong mainly to the minorities of Hungarians, Serbs and Bulgarians (

Table 2). Analysis of the documentary evidence and of the empirical information we gathered demonstrates that activities designed to preserve the identity of ethnic minorities take place preponderantly in towns and localities where minorities make up at least 20% of the population or where they number not fewer than 200. In places where having notices displayed in the language of the ethnic minority, and its use alongside Romanian in local administration, are current practices, it is clear that there is ethnic-identity consciousness and a concern for its continuance, so we investigated them in particular (

Figure 1).

Regarding regional identity, the field study reveals a strong attachment of the inhabitants to the place of residence and to the Banat region. The meanings and implications of this result are multiple. For the majority of inhabitants, the mental boundaries of Banat largely correspond to its configuration at the point at which it was incorporated into the lands of the Habsburg Empire in 1718 (when it was bounded by the Carpathians, the Danube, the River Tisa and the River Mureș), even though the region has been subdivided and administratively reorganised a number of times since 1918 (

Ancuța 2008). Other studies attest to the fact that historic Banat has remained in the collective mentality as a positive model, opposed, in some contexts, to the present-day territorial organisation, and that this is felt by indigenous Banat Romanians as well (

Babeți 2008).

From the answers given by the interviewees and the opinions expressed by the respondents to the questionnaires it turns out that, in their imagination, Banat remained “whole”, considering that the state border drawn after the First World War separates two countries or two states, but it cannot break the intimate connection identity among the inhabitants. The questionnaires show that 42.83% of Hungarian and Bulgarian respondents maintain direct and stable connections with people who speak the same mother tongue in Serbian Banat. A representative of the Bulgarian community said that “I do not feel like a foreigner when I cross the border in Serbia, in the old Banat. The official language of the country differs, but the old architecture of the villages (as it was built in the Austro-Hungarian period) and the custom of using the mother tongue, mutual tolerance between ethnic groups, have remained as they were and are today in The Romanian Banat”. Another respondent, a Hungarian, remarked that: “in the villages across the border we still have relatives and, in the cemeteries, there are buried relatives of our ancestors. Banat was divided as a territory, but we have our history and our tradition”. A Serbian respondent remarked that “Banat means the whole territory, as it was, between the Tisza, the Mureș and the Danube. I am a Serb from Banat, and across the border, I go to Banat. There, I meet Serbs, Hungarians, Romanians—also from Banat. The official name Banat has been retained in Serbia”.

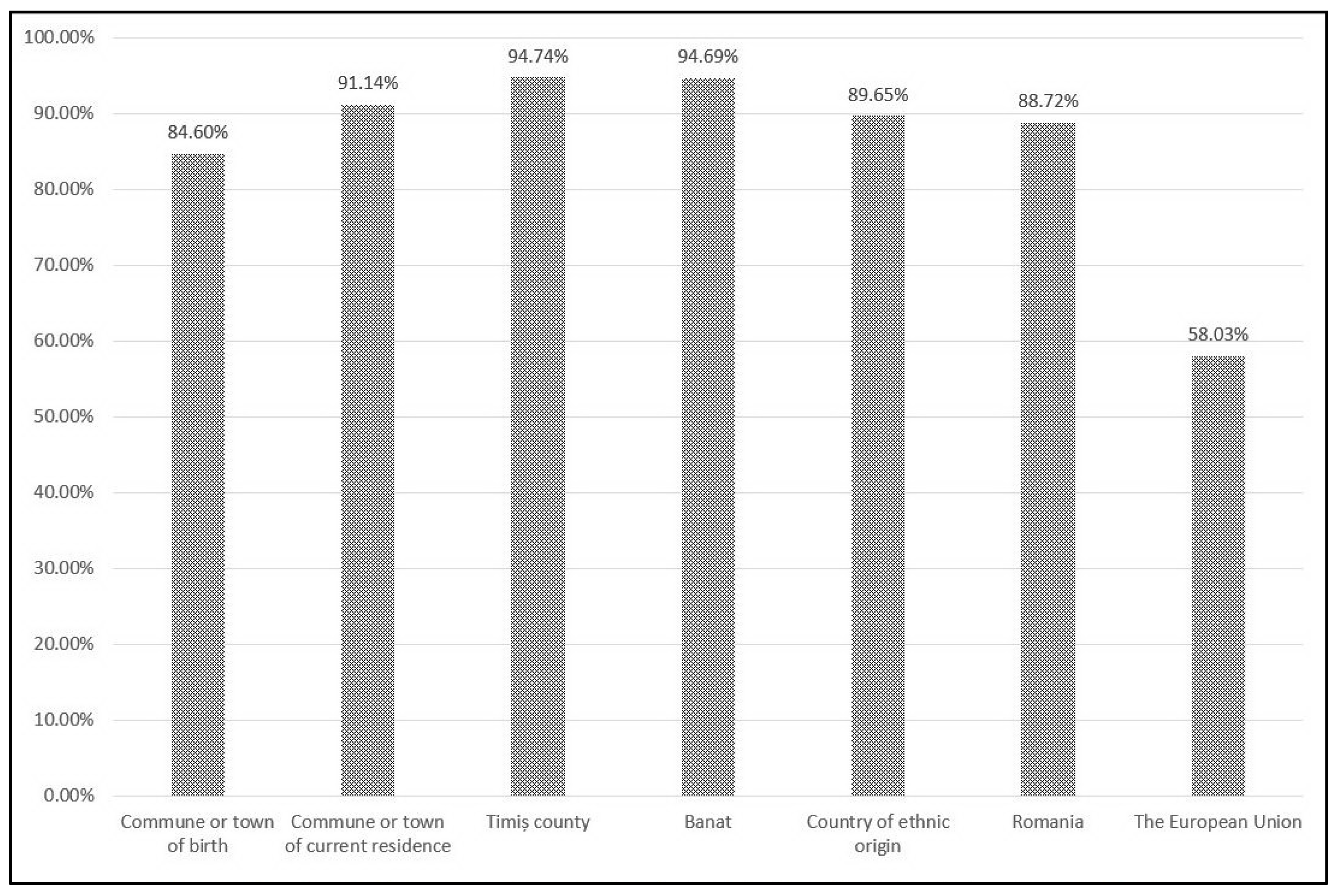

With the help of the questionnaire, we aimed to evaluate, by awarding points, the degree of attachment that the respondents show in relation to a series of different territorial constructs (Banat, Timiș County, EU Romania, etc.). Results gave regional/local belonging the highest scores, closely followed by country of origin and host country (

Figure 2). As completing the questionnaire allowed them to express themselves freely on this issue, anonymously and without the constraints of a hierarchy, a significant proportion of respondents gave the same or a similar number of points to place of residence, region, host country and country of origin. We may interpret these responses, with their extremely similar scores, as a proof of the solid integration, at the mental level, of the territorial constructs under consideration.

Regarding interculturality and intercultural co-construction, field studies conducted by psychosociologist Alin

Gavreliuc (

2003) two decades ago show that, for example, a Romanian from Banat feels closer to a Serb or a German from Banat than to a Romanian from another region of Romania. The author also specifies that the ethnic minorities he questioned expressed their firm solidarity with the Romanians in Banat. This regional otherness has been explained, on the one hand, by the interethnic solidarity built in at least two centuries of coexistence and, on the other hand, by the common regional identity, regardless of the assumed ethnic identity. One respondent, a school inspector for Hungarian medium instruction, underlined that “activities carried out in common demonstrate that we face similar problems, and this has the effect of bringing people closer together, regardless of their nationality”.

The Church has always been an important social factor that has a constant impact on cultural life (

Cobianu-Băcanu 2007). Where the religious community is composed of representatives of more than one ethnic group, as is the case, for example, in the Roman Catholic parish of Sânnicolau Mare (Romania), the priest takes an active involvement in strengthening a climate of tolerance and interethnic solidarity. More than that, he mentions the help he received from the Romanians of Makó (Hungary), on the occasion of some lay religious and cultural activities that took place in collaboration with the Roman Catholic community there. This was a vivid example of intercultural solidarity, given that not all the participants from Sânnicolau Mare knew Hungarian well, any more than all the Romanians from Makó knew Romanian. The priest added the detail that when social and cultural events take place, representatives of other denominations and ethnic groups are invariably invited, and that this practice is widespread in the region across all confessional communities.

Our field research in the years 2020–2021 indicates the same ethnic tolerance shown in respondents from all three ethnic groups studied, in that over 65% of respondents would have no objection to having a neighbour of another ethnicity or that he or a close relative marry someone of another ethnicity. However, respondents declared their attachment to Romania in a proportion of over 88%, which is why we are inclined to believe that their positive attitude towards Banat residents of other ethnicities has a proactive significance and is not mainly directed against Romanian residents from other regions of the country (

Gavreliuc 2003).

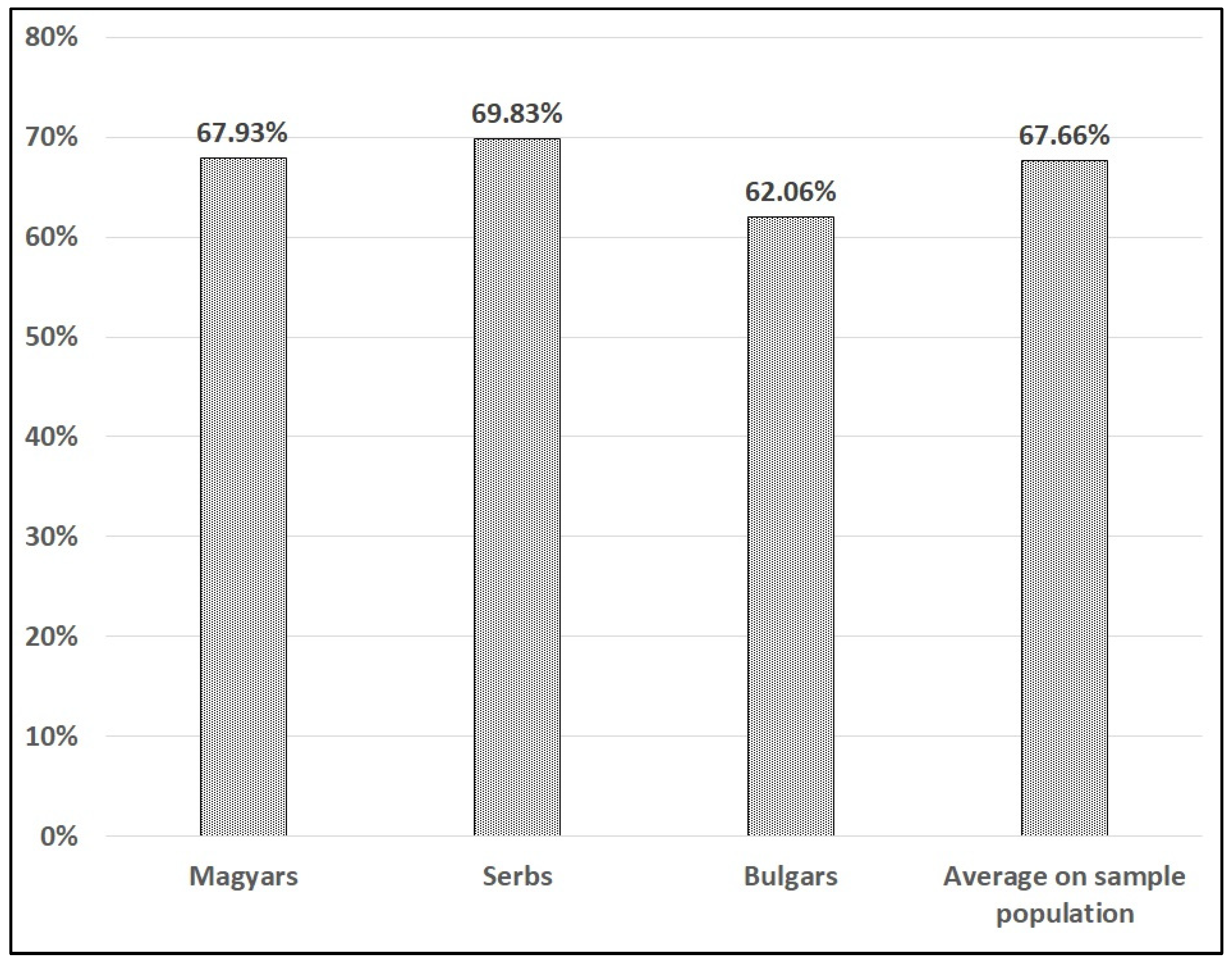

The questionnaire survey conducted by us in the mentioned ethnic minority communities also revealed great openness on the part of respondents towards members of other ethnic groups. When asked whether they would accept neighbours of a different ethnicity, a majority of 75.33% replied in the affirmative. The level of acceptance of people of a different ethnicity into one’s extended family is high. Over 67% of the respondents declared that they have members of another ethnicity in their extended family (

Figure 3). Many of the respondents proved to have grade I (31%) and II (36%) relations of other ethnicities, most frequently Romanians.

Observations made in the communities studied also demonstrate the plurilingualism of respondents. The direct observations made in the studied communities attest to a large number of respondents who know languages other than their mother tongue and the official language, Romanian. This confirms the results of other previous studies, which indicate the habit of the people of Banat to learn the mother tongue of childhood friends or people from extended family (

Neumann 2012;

Micle 2013;

Para and Moise 2014). This opens the way for cultural values to migrate inside those multi-ethnic communities (

Cobianu-Băcanu 2007).

A further factor in intercultural co-construction is the existence of a shared historical and cultural patrimony. Both historical personalities of different ethnic origins and monumental buildings have symbolic value for all Banat residents. Efforts to preserve this heritage are undertaken in common, with the majority Romanian population also participating, even though some of them arrived relatively recently (in the past 20–30 years) from other regions of the country. To take only two examples, Nakó Castle in Sânnicolau Mare, built by Count Kálmán Nakó, a descendant of the Nacu family, Aromanians who migrated here from the Balkans and became Hungarian in the 18th century, and the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, born in the same town, are both symbols that have been adopted by the entire local population.

We also find people of different ethnic origins participating in the folk music and dance ensembles of the region. The Doina Ensemble (Romanian) and the Sveti Sava [St Sava] (Serbian) Ensemble both have Romanian, Serbian, Bulgarian and Hungarian dancers and singers/musicians as members performing together. The situation is similar when it comes to local festivals: the Jaku Ronkov interethnic Festival in Dudeștii Vechi (a Bulgarian community), the Lada cu Zestre [Dowry Chest) Festival, and the Festival of Ethnic Groups; the last two organised by Timiș County Council. Representatives of all the ethnic minorities in Romania, Serbia and Hungary are invited to these events.

The practice of cross-border relations between the minority communities we have studied in Timiș County and their co-nationals in Serbia and Hungary, involves a number of social, cultural and economic aspects.

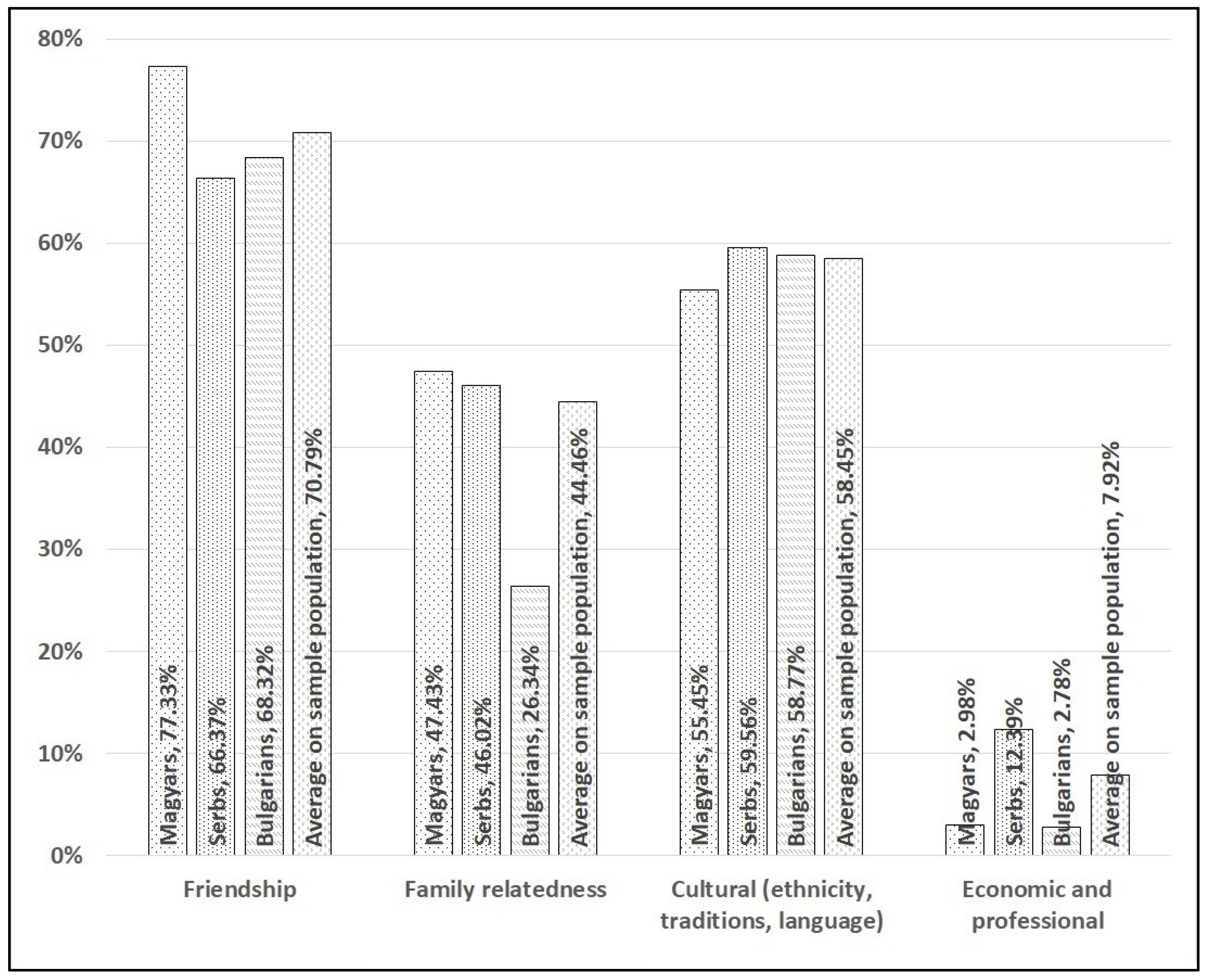

The questionnaire method employed in our field research allowed us to assess the frequency, strength and nature of cross-border contacts between people living in the communities studied and their co-nationals in neighbouring countries Serbia and Hungary. The most important motive for maintaining these contacts tended to be interpersonal relations; affinities of a cultural and especially language-based nature were invoked less frequently (

Figure 4).

Field research demonstrated that ethnic Hungarians in Timiș County have a high level of interest in cultural relations with their country of origin. 55% of ethnic Hungarian respondents to the questionnaire mentioned cultural activities and the preservation of the language and of the historical tradition as motives for maintaining a relationship with their co-nationals in their country of origin (

Figure 4). Turning to the relationship between Hungarians in the area of study and Hungarians in Serbia, this cultural motivation was mentioned by 76% of respondents.

A different picture emerges for relations between Romania and Serbia regarding the Serbian minority in Timiș County. The support given by Serbia to Serb communities in Romania has been less solid, principally for economic reasons and because of the policy of Belgrade. During the socialist period, the cultural support Yugoslavia gave to Serb minorities in other countries was limited. After the Yugoslav Federation broke up, the internal problems of Serbia imposed even greater limitations on the possibility of such support being provided (

Rusinov 2002;

Glenny 2012). For the representatives of the Serb communities in Timiș County, the cultural motivation for maintaining contact with their co-nationals in their country of origin was mentioned by 59%, similar with to the level among Hungarians. As for the relationship with Serbs in Hungary, cultural motivation was invoked by 74% of respondents.

A percentage of 58.77% of Bulgarian respondents invoked a common language and the preservation of ethnic identity when asked about relations with their co-nationals in their country of origin; for relations with their co-nationals in neighbouring Serbia, the figure was 78%. It is worth mentioning that the Bulgarians in the area of study and those who live in Serbia both speak a dialect form of Bulgarian that differs from the literary language.

A surprisingly high percentage of questionnaire respondents stated that they had relatives in their country of origin—over 44% (

Figure 4). Bearing in mind that the questionnaire part of our research took place in old rural communities in which families are interrelated to a significant degree, it is possible that some families may maintain links with relatives over the border in which the relationship was formed many generations back. We should also recall that before the 1918 partition, the communities in Banat maintained active relations, especially as some localities came into existence as the result of an influx of inhabitants from localities that are now in Hungary or Serbia, close to the current border. In the rural world, extended family links are extremely resilient (

Bădescu 2011).

The percentages of different areas of interest as the basis for relations with subjects’ country of origin (

Figure 4) provide a picture of a kind of collective mentality in which interest in interpersonal relations and in relations with one’s immediate social milieu outweighs interest in the preservation of culture. Respondents stated that they were more concerned with interpersonal cohesion than with voluntary initiatives aimed at preserving culture. Family, followed by one’s circle of friends and the local community, were the most significant factors, followed again at an appreciable distance by regional and transregional considerations.

Regarding the development of relations between ethnic minority communities and the social perception of territory, the points which nuance this issue to the Hungarian minority were highlighted as follows:

- -

The impact of bilateral collaboration between Romania and Hungary on the preservation of identity in Hungarian ethnic minority communities.

- -

The influence of the process of EU integration on relations between Romanians and the Hungarian minorities, and between the latter and their adoptive country.

With reference to the impact of bilateral relations between Romania and Hungary, in all cases respondents invoked the direct effect of bilateral relations between the two neighbouring countries.

Interviewees emphasised the shared regional identity of Banat people on both sides of the border. The majority of their mentions of Hungarians in Serbia and Hungary made reference to localities in historic Banat.

They also mentioned the fact that the status of Hungarians in Banat is different from that of Hungarians in Transylvania: “In Transylvania the Hungarians live in compact communities, while in Banat we are like in the Diaspora. It is natural that Hungary should help them more than us. We have relationships with both the Hungarians and the Romanians in Makó” (Ando Ioan Attila, priest, Sânnicolau Mare). This distinction between the Hungarians of Banat and their co-nationals in Transylvania is evident from other interviews besides this one.

Romanian-Hungarian bilateral relations have facilitated collaboration in a variety of areas and cross-border visits by both sides, the participants in which belong to a wide range of ages, from school pupils to those of working age to retired people. In seven of the eight interviews with representatives of the Hungarian community there were mentions of the twinning of towns and communes on both sides of the border and of the twinning of schools and cultural organisations.

Between 2007 and 2020, projects were implemented that aimed at objectives such as sustainable development, risk management, conservation of natural and cultural heritage, human resource development, tourism development, cross-border movement, education and research. In the studied region, by far, the most active was the relationship with Hungary. (data source:

http://www.huro-cbc.eu/,

https://interreg-rohu.eu/ accessed on 3 December 2021). At a short distance were the projects implemented by Romania in collaboration with Serbia (data source:

https://www.romania-serbia.net/ accessed in 3 December 2021). Romanian-Ukrainian and Romanian-Bulgarian bilateral projects have not been implemented, as Timiș County is outside the target area of these programs, but the Bulgarian and Ukrainian communities are included in other Romanian governmental and European projects, of course, with a much lower impact. The field study revealed the openness of all interviewees to be actively involved in the implementation of such projects in the future.

The moral and material support that institutions and communities in Hungary supply to their opposite numbers in Romania should not go unmentioned. The founder and coordinator of the “Kék Ibolya”, a Hungarian folk dance ensemble based in Sânnicolau Mare emphasised that “we have been helped more by the Hungarians of Hungary than by those in Romania”.

The main political party of ethnic Hungarians in Romania is DAHR (Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania). In the same context of the aid received by the Hungarian minority ethnic communities in Romania from the country of origin of the ethnic group, Hungary, the Sânnicolau Mare DAHR president highlighted the constructive role played by their partners in Hungary, which joined the EU earlier than Romania, in helping them access EU funding and implement projects. Hungary has made a financial contribution, through state programmes, towards the renovation of buildings in which Hungarian medium teaching takes place, including the Bartók kindergarten and the Assembly Hall of the Gerhardinum Roman Catholic High School, both in Timişoara. The Szeged folk dance ensemble supports Hungarian folk dance groups in Timiş County (Bokréta, Eszterlánc, Búzavirág, Csűrdöngölő, etc.). Schools and kindergartens which teach in Hungarian have received educational materials and toys from various foundations in Hungary. “A large number of Romanian-Hungarian combined projects have been implemented, and these have made a great contribution, directly or indirectly, to the preservation of ethnic identity (K.F., school inspector, Timișoara).

In conclusion, successful bilateral projects have strengthened relations between the countries, while dialogue and intercultural co-construction have improved the social perception of Hungarians and Hungary among their Romanian partners.

Hungary and Romania’s common membership of the EU plays an extremely important role in the preservation of the ethnic identity of Hungarians in Timiș County.

All respondents to interview referred to the advantages of this common EU membership in ensuring free movement of persons and the opportunity to access EU funding for shared projects. Responses to this question both affirm and nuance this common belonging to the Banat space. More than that, the Sânnicolau Mare DAHR president was at pains to specify that “the EU supports cross-border collaboration in a concrete way, which means that belonging to the EU is of mutual benefit both for the Hungarian community and for the Romanian community”.

Again, respondents underlined the positive collaborative relations that the Roman Catholic parish of Sânnicolau Mare, in which ethnic Hungarians are in the majority, is developing with the Romanians of Makó and the surrounding rural area. The fact that the Hungarians in Romania know Romanian and the Romanians in Hungary know Hungarian has smoothed the way to cross-border and intercultural communication between these Banat residents who live in different countries. In response to this question, the same interviewee specified that “it is difficult to say whether the good relations between Romania and Hungary are due to the EU. Before 1990, relations between Hungary and Romania were controlled by the USSR. In that period Hungary did not give support to the Hungarian community in Romania”—leaving one to understand that the best way the two countries can develop a closer relationship is via bilateral communication. The other respondents underlined that the policy of EU integration had facilitated the moves Hungary had made to come to the aid of Hungarian communities in Romania.

Romanian-Serbian cross-border relations were interpreted quite differently by respondents to interviews. One of these, with twenty years’ involvement in promoting the folklore and traditions of the Serbian community in the west of Timiș County, stated that “political relations very much depend on the international political context and have nothing to do with people who live in the zone of overlap”. The majority of the Serbian respondents recalled, with disappointment, the support the Romanian government had given NATO in 1999 when the North Atlantic allies were bombing Serbia. Feelings of empathy were expressed towards Serbs in the mother country, but without this generating resentment towards Romanians. Something else that came out in the interviews was regret that Serbia had not been able to give any solid support to their co-nationals in the Romanian Banat. At the same time, they referred to the empathy they experience from Romanians, especially from those in the region which Serbians and Romanians inhabit together. The position of a 34-year-old respondent (much younger than the previously mentioned Serbian respondents), coordinator of a Serbian folk ensemble from Sânnicolau Mare is more proactive. He sees Romania’s cross-border collaboration with Serbia as positive and considers that “Through these cultural projects the community (not only the Serbs in the community) is enriched culturally, plus it is an opportunity for the community to gather in a spirit of solidarity. These cross-border projects also bring together several ethnic communities and are good for cultivating respect for diversity, socialization and interethnic understanding. This culture of diversity and inter-ethnic communication is specific to Banat, on both sides of the border” (the respondent refers to Banat within its historical limits).

With reference to efforts to preserve the identity of Serbians in the area of study, two former Serb minority members of the Romanian Parliament deplored the massive infusion of cultural elements from regions of Serbia, since these are alien to the local Banat Serb ethos. It is noteworthy that all respondents identified Timiș County as their “homeland of origin” and recalled that there had been a continuous Serb presence there since the medieval period. There consequently exists, in the Serbian communities of the area studied, a specific local culture, and this is under threat precisely from the help and influence that have come from Serbia.

The impact of cross-border relations differs very much from case to case. All the Serbian respondents referred to the economic benefits of the informal trade across the border that functioned until 1992, but also stated that their host country, Romania, is currently giving them more substantial support towards preserving their local ethno-cultural identity.

As for the impact of the process of EU integration on Romanian-Serbian relations, via projects that have a direct effect on their communities, they mentioned that “the benefits of these EU projects for our community are still awaited” (by the members of the communities). In the respondents’ opinion, intercommunity cross-border projects without EU support had a greater impact in the cultural sphere. Exchanges, reciprocal visits and activities undertaken at the local level through inter-institutional and intercommunity collaboration consolidated the empathetic relationship and reinforced a reciprocally positive attitude on the part of both Romanians and Serbs.

In the Bulgarian Catholic communities in Timiș County, cross-border relations with Bulgaria are more apparent in their institutionalised forms. The relatively greater distance to the country of origin from which they emigrated at the end of the seventeenth century, along with the fact that Timiș County does not share a border with Bulgaria, have made interpersonal cross-border relations difficult. Consequently, the initiative for links with their country of origin and for links with other ethnic Bulgarian communities, this time in Serbia, has chiefly been of an officially organised nature. “Collaboration between Romania and Bulgaria definitely has a positive effect both on the Bulgarian community in Romania and on the community of Romanians in Bulgaria” (C.N., representative of the Union of Bulgarians in Banat Romania). The moving force behind the establishing of links has in most cases been cultural or social.

As in the case of the other minorities studied, the Banat Bulgarian respondents invoked the support which they enjoy from their host country in preserving their culture and maintaining links with their country of origin. Through their official representatives and through the practice of informal contacts, the Bulgarian minority in Banat has acted as a bridge on which the two countries, Bulgaria and Romania, have met and become closer.

6. Conclusions

The multi-layer cross-border interactions that take place between the communities studied and the countries neighbouring Romania in the western part, Serbia and Hungary, have deep roots and are manifested in an active way. The regional identity and intercultural co-construction of the Banat social landscape have always nourished interpersonal and institutional connections. Both Romania’s good neighbour policy and European integration have encouraged these links.

Deconstruction of territory in the cross-border area studied brings to light multiple elements of difference in the perception of the territory and its boundaries. These stem from the reconsideration of the territoriality and regional personality of Banat. The territorial integrity of Romania and of the neighbouring countries are not the object of live debate. Again, few respondents have plans to (re)emigrate to the country of origin of their ethnic group. The majority of respondents stated that they only make visits to their country of origin and cultivate socio-cultural relationships with their co-nationals. This assumption of a threefold identity—ethnic, civic-national, and regional—generates particularities in the perception of territory and in its cultural construction.

On the other hand, the intercultural solidarity specific to Banat, which we have identified in Timiș County, is favourable to the cultivation of cross-border relations in various domains between the three neighbouring countries. The representatives of minority ethnic communities whom we researched declared themselves interested in contributing to the improvement and development of these relations, with an awareness that their position in Romanian society was also influenced by relations between their host country and the country of origin of their ethnic group. Likewise, the sentiment of regional belonging that Banat people feel (conscious as they are that Romanians make up a majority in Banat and that two-thirds of Banat is in Romania), and the benevolent attitude of the Romanian authorities, are reflected in the strengthening of a feeling of loyalty towards Romania as host country. We should mention in this context that it was extremely difficult to achieve a hierarchy of current territorial constructs (Romania, Banat, Timiș County, place of residence) based on the feelings of belonging expressed by questionnaire respondents. Many refused to put these constructs into a hierarchy and stated firmly that they perceived them as a single unit that could not be divided.

The local ethno-cultural diversity has lasted for about 250 years in Timiș County and in the whole Banat region, without having undergone conflicts or deep structural reshuffles, except for a slow process of increasing the share of the basic national element in each of the three countries, which is divided in historical Banat. This diversity is animated by coexistence, co-participation and intercultural exchanges, with the preservation of local identities and regional plurality. This creates the conditions for ensuring equity in the social life of local authorities and for participating in decision-making, regardless of culture or ethnicity.

The cross-border relations with the countries of origin of the analyzed ethnic communities from Timiș County give an extra maturity to the local communities, through multidirectional dialogue across borders and mutual sharing of good practices. These are also favorable premises for preserving local identities and increasing quality of life through regular cross-border contacts and accessing local development funding, based on mirror projects, both in Romania (Timiș County) and in countries of origin of the researched minority communities.

From the answers to the questionnaires and interviews, it appears that the socio-cultural model of Banat ensures good resilience in the local communities. Sharing complementary, sometimes competing values, they are attractive and efficient competitive environments, able to better cope with the restructuring induced by glocalization processes: they attract investors, promote endogenous development, retain young people and project optimistic prospects. There are some differences, however, and they depend on the level of development, the degree of interest and involvement of the country of origin, as well as the entrepreneurial spirit of each community.

This study focused on the cross-border area of Timiș County, and confirms aspects of the concept of social sustainability revealed in the international literature. The focus was on the positive aspects of social cohesion, as a result of the evolution of society as a whole (

Rasouli and Kumarasuriyar 2016;

Eizenberg and Jabareen 2017). The European agenda also places an important position on social sustainability, in the context of the process of European integration and cohesion of member countries (

Biart 2002). We emphasize in this context that historically constructed intercultural social cohesion and regional identity, revealed at the level of the studied region, contribute to the increase of cohesion between countries through social solidarity, economic cooperation and cross-border political cooperation.

Compared to previous studies, this study complements and empirically substantiates, through applied field research, the intraregional and cross-border intercultural interactions of the Hungarian, Serbian and Bulgarian ethnic minority communities of Timiș County, by revealing the purpose and meaning of these interactions. This issue has been addressed in the current context of the European integration process. The main advantage of combining documentary studies with field hypothesis testing is revelation of the reality and the development of previous studies on this complex issue, which does not support nuances in the context of the historical evolution of the region. The main disadvantages that accompany field studies derive from the subjectivism of the respondents and from the influences of the historical context in which the field research is done. It is desirable that research on this issue be done longitudinally, in order to judge influences from the geopolitical and economic systems on the social imaginary of the studied communities.