1. Introduction

Quality has evolved to being one of the most important concerns in higher education (

Harvey 1998). Even so, establishing the definition of quality in higher education is not easy, so much so that the only consensus on the subject is the recognition that quality in higher education is a complex, confusing, and even slippery matter (

Dicker et al. 2019;

Schindler et al. 2015;

Elassy 2015;

Harvey and Green 1993).

High prestige multilateral organizations have also contributed little to this subject. For example, the United Nations (UN) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) have both previously made public statements and proposed agendas which would establish quality of education as a collective goal of paramount importance; however, they have not been able to provide a clear and precise definition for the term educational quality.

Therefore, the conceptualization of quality within higher education remains a terrain that is both intricate and inhospitable where the concept itself is at risk of becoming a mere tool of ideology: quality declared as an objective could end up legitimizing (or at least justifying) any policy, program, decision, or action. In the opposite direction, the quality policies applied from the government spheres or in the HEIs usually condition the perception of the agents and their preferences on the way in which educational quality should be defined and pursued.

In Mexico, where this research was carried out, concern about the quality of higher education arose in the late 1980s after a stage of “disorganized growth” (

Moreno Arellano 2017) which contributed to the application of clientelist criteria in the distribution of public resources, which, in turn, reduced the impact of investments on a real improvement of higher education. The speed of the expansion also meant that it was impossible to guarantee the qualification of teachers and researchers. The economic crisis also contributed to the degradation of teachers’ salaries and there were fears of the desertion of the most qualified.

In those years, diverse public programs were launched with the intention of rationalizing the higher education sector and encouraging the quality of teaching. Most of them adopted an external evaluation and quality assurance approach that consolidated over time. The National Committee for the Assessment of Higher Education (CONAEVA), the Interinstitutional Committees for the Assessment of Higher Education (CIEES), and the Higher Education Accreditation Board (COPAES) were erected between the 1980s and the 1990s. Although internal evaluation was sometimes promoted, a culture of evaluation and accreditation of both study programs and professors in instances external to their own HEIs extended in the sector.

With the new century, quality accreditation at various levels became a necessary condition for access to government financing programs (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2020) such as the Comprehensive Program for Institutional Empowerment (PIFI), which later became the Program for the Improvement of Educational Quality (PFCE). Although voluntary, these programs have been essential for Mexican HEIs due to the perennial scarcity of their resources (

López Zárate 2012) and have contributed to consolidating a culture of external evaluation and accreditation of institutional and individual academic quality, closer to a quality assurance approach than to a quality improvement one (

Biggs 2001).

Specialists in the topic of the notions of quality in higher education posit that the term quality takes on different, but not incompatible meanings (v.g.

Cardoso et al. 2016;

Harvey and Green 1993). This stance invites us to think that any project inclined to gain a consensus on the subject of educational quality is doomed to failure, for the simple fact that is it impossible to please everyone all of the time. Put another way, behind the words “educational quality”, there are hidden perspectives, intentions and subjective symbolism of the various actors and interested parties (

Trinidad et al. 2021) involved in one way or another within higher education. This explains why the landscape of conceptualization of quality in higher education has remained especially elusive in higher education institutions (HEIs), wherein there exists greater numbers of interests and actors than in any other institution (

Prisacariu and Shah 2016;

Harvey and Askling 2003), except for political institutions.

It is precisely a political perspective that can shed light on this subject. For authors such as

Marshall (

2016),

Skolnik (

2010),

Becher (

1999), or

Astin (

1980), the notions of quality hide behind political positions on what education should be and, ultimately, different positions on educational policy and management, hence the numerous and diverse meanings of the term. In the same vein, (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2015, p. 674) state that quality concepts are “on a par with the political notions of right and left” and can have the same use that is attributed to the said notions in the study of political attitudes.

This thesis about the political content and sense of the notions of quality is interesting because it returns the concepts of quality into the realms of science. In other words, the notions of quality when raised as descriptors of the political positions of actors can become scientific categories, and their relation to other categories and phenomena makes them relevant for the study of HEIs (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2017). This thesis requires specifying the different meanings that quality can take, which is very different from trying to prioritise (or impose) one meaning over the rest.

The true test of the value of quality concepts depends on finding empirical evidence of the relation between agents’ notions of quality and other relevant variables in the analysis of HEIs. Recently, some papers have begun to research this matter, wondering, for example, if the actors’ (students’ and university professors’) preferences for quality concepts are dependent on their social, educational, and professional position (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2016;

Jungblut et al. 2015;

Cardoso et al. 2013).

This article provides a similar contribution. This research seeks to establish whether the job satisfaction of teachers in HEIs depends on their perception of whether there is any disagreement between them and their institution about the concept of educational quality.

This hypothesis has a solid foundation within the literature on higher education and the peculiarities of the organization of academic work. Unlike other organizations who are dominated by their ‘instrumental value’, that is to say, their ability to achieve set objectives, HEIs are organizations where the beliefs and values of their members (their culture) are definitely transcendental, but not always peaceful elements. In one of his classic works,

Clark (

1983, p. 72 ff.) devotes an entire chapter to thrashing out the beliefs that are the working base of HEIs and its parallel with religion due to its doctrinal character and highly emotive content. For Clark, however, the abundant culture and beliefs within HEIs do not form a perfectly coherent whole, but rather are constructed through the intersection of various cultural references, such as the discipline, the institution, or even the academic profession, whose singular character is stated by Clark himself in other studies (

Clark 1977). In particular, the professional character of organizations operating in the sector of higher education has also been featured (

Mintzberg 1979) to explain, among other things, a greater affection of academics for the values of the academic profession than for the decisions and strategies of the governing bodies of higher education institutions. This feature also underlines the transformations that in recent times HEIs are suffering along with the conflicts that derive from them both tangibly and symbolically. In the latter sense,

Mather et al. (

2009) describe the recent process of the erosion of professionalism in the higher education sector in the United Kingdom (UK) and its consequences in the shape of intensification of the workload and de-skilling of teachers. Although Mather et al. did not investigate how the reforms have affected the job satisfaction of teachers, the way the authors describe the changes in the new working conditions implies that the effect on the satisfaction of teachers has been negative. The work by Mather et al. is also interesting because it suggests that all these transformations occur in an environment of conflict between two antagonistic interpretations of academic work: the traditional academic ethos, which the authors associate with public service, and the new ideology of managerialism that has been gradually introduced in the public sphere and in the field of higher education in particular (

Benavides et al. 2019;

Jemielniak and Greenwood 2015). The conflicts within the realm of ideas and the tangible consequences upon working conditions are seen as connected in the study by Mather et al., as well as in this study.

In short, the literature repeatedly reports the normative character of HEIs (

Birnbaum 2004) and therefore the influence that values exert on their operation and on the individuals working in them. The literature also describes HEIs as spaces in which conflicting values can coexist, and the consequences that these conflicts have upon the working conditions of academic personnel.

According to the above approach, this paper presents at least two novelties. On one side, this research employs the reaction of academic personnel’s different ways of understanding quality as a method of approach to conflicts that occur in the symbolic realm of HEIs. Secondly, the purpose of the paper is to identify whether the discrepancies perceived by staff between their own values and those prevailing in the institution cause job dissatisfaction, i.e., this research incorporates the construct of job satisfaction in the analysis, a deeply rooted construct in the field of psychology and human resources (

Locke 1976), and in the scope of higher education (

Jung et al. 2017) but not in the literature that specifically addresses the operation of HEIs (cf.

Rhodes et al. 2007).

The objectives of the paper are divided into two. First, to describe the preferences of academics at four Mexican university centres on the notions of quality in higher education; and second, to determine if the perception of a discrepancy or inconsistency between their own priorities and those of the institution lead to job dissatisfaction among teachers.

The article is split into the following sections. After this introduction containing the theoretical and conceptual framework, the second section describes the data and analysis techniques used. The third section describes the opinions of the faculty. Their responses inform the appropriate ones are the concepts of quality that academics most often adhere to. Their answers inform about the concepts of quality that academics adhere to most frequently. The third section also confirms the disagreement between the notions of quality preferred by academics and those that they attribute to their institutions, and then explores the relationship between this disagreement and teachers’ job satisfaction. The article ends with a discussion section and conclusions.

2. Data and Methods

The data used in this paper was obtained through a survey. A first draft of the questionnaire was designed by the authors and is based on previous literature and research. This first draft was submitted to a panel of experts and a pilot test at the Centre for Innovation and Quality of Higher Education of the University of Guadalajara. As a consequence, several changes were made to the questionnaire. The questionnaire contains 60 questions divided into five sections. For this research, only 21 questions related to notions of educational quality and satisfaction were used, in addition to some identification questions that served to introduce some control variables in the models, which will be explained later. (

Table 1)

The survey was conducted in four university institutions in Mexico: University Centre for Economic-Administrative Sciences (CUCEA), University Centre for Health Sciences (CUCS), University Centre of the Valleys (CUValles), and University Centre of the South (CUSUR). These four centres constitute a sample that adequately represents the characteristics of Mexican university as they include metropolitan as well as suburban/rural areas, as well as the different scientific disciplines and fields of study.

In each centre, the collaboration of all the academic staff was requested, particularly 1257 academics in total. The questionnaires were handed out in person using a paper form and were filled out by the teachers on site. All participants were informed of the objectives of the research and the rest of the relevant information about it, as well as the anonymous nature of the survey. The administration of each centre provided lists of teachers including information on their location, as well as dependencies for carrying out the surveys when necessary. The interviewers located all the personnel present at the centre and requested their collaboration. The process lasted one or more working days, depending on the case. This method was chosen to take full advantage of the close collaboration between the researchers and the administration of the centres, and so to increase the response rate with respect to online surveys. A total of 911 responses were obtained (72%).

The information collected in the questionnaires was manually registered in SPSS (version 26.0.0.0) for later analysis.

Among the questions contained within the questionnaire, this research uses the following sections:

Nine questions were posed about the extent to which each respondent adheres to nine operational concepts for quality, and nine others about the extent to which they believe their university adhere to the same concepts. The nine quality concepts presented are based on a revision of the literature and previous research (

Harvey and Green 1993;

Watty 2006;

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2016;

Jungblut et al. 2015). In all cases, a Likert type scale was used with five response categories, from “completely disagree” to “fully agree”. The central category was “Neither agree nor disagree”. For the application of quantitative analysis techniques, these scales were assigned numerical values as follows: “Completely Disagree” = 0 to “Completely Agree” = 5. A principal component analysis was carried out (see

Table 2), which confirmed the presence of three dimensions of the notion of quality, explaining 61.4% of the variance of the original items. Each component is more strongly linked to three of the original items, and all groups of the three variables exhibit satisfactory levels of internal consistency (with Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.6 in all cases). The set of nine original items also achieve satisfactory levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.79).

Three questions were posed about the satisfaction that respondents feel about their job in general and about two specific facets of their working conditions: opportunities for promotion and salary received. Scales used to rate levels of satisfaction were again based on a five point Likert scale ranging from “Very Dissatisfied” to “Very Satisfied” with an intermediate category defined as “Neither Satisfied nor Dissatisfied”. These three items presented a high degree of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.81). However, in the analysis it was preferred to use each of the items separately with the intention of offering a more complete and detailed description of job satisfaction in each domain of work. Moreover, in accordance with part of the literature on job satisfaction (

Main et al. 2019;

Bentley et al. 2013), it was preferred not to translate respondents’ responses into numerical values. For the regressions described below, these three variables were transformed into dichotomous variables, with a category for those respondents who reported “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with their work (or some aspect of it) and another category for the remaining responses.

The methods used to establish the relationship between the concepts of quality and job satisfaction were as follows.

The amount of disagreement of academic staff with the quality dimensions implicit in their university’s culture was measured employing the difference between the professors’ responses about their own notions of quality and their answers on the notions that they attribute to their university. The results obtained for each of the nine operational concepts were added in three blocks according to the results of a principal component analysis, namely standards and objectives of the institution, transformation of the students and attention to social needs, and stakeholder expectations.

The relationship between the disagreement felt by teaching staff and their job satisfaction was analysed by logit regressions in which the three variables measuring disagreement acted as regressors. Individual demographics and professional characteristics (age, sex, years of service, current management position, and type of studies) were introduced into the regressions (

Table 3 contains descriptive statistics for the quantitative regressors in the model). Current management position distinguishes between staff who were in a management position on the day the questionnaire was passed and those who were not. Type of studies distinguishes between staff teaching in studies with a straightforward relation with a professional field (for instance, engineering, medicine, or law) and the rest. The use of logit techniques is consistent with the idea that job satisfaction scales are devoid of the virtues of quantitative variables. However, they do allow a clear distinction between people who express job satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) and the rest (

Bozeman and Gaughan 2011). For the specification of the models, a stepwise strategy was used, consisting of the iterative elimination of the least significant explanatory variables, if this did not represent a significant worsening of the quality of the model as a whole. As a criterion for the elimination of variables, a likelihood ratio test with a sensitivity of 0.1 was used.

3. Results

3.1. Conceptualization of Education Quality

Agencies that evaluate the quality of HEIs, or those that recommend and implement policies aimed at reforming them, find it difficult to decide what should be understood by educational quality (

Jungblut et al. 2015). It has also been found that individuals in HEI management positions hesitate when asked about their understanding of quality education (

Goff 2017;

Scharager Goldenberg 2018), and that academic staff who do not have managerial responsibilities tend to speak out in favour of notions of educational quality which are essentially different from that of managers (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2015). Notwithstanding all of the above, various surveys carried out in HEIs from different parts of the world show that there is an idea of educational quality that better accommodates the preferences of academic staff in general and receives widespread, virtually unanimous, support from faculty.

Harvey and Green (

1993) proposed five categories to reflect the different meanings of quality within the context of higher education: quality as something exceptional, quality as consistency in achieving certain results, quality as fitness for purpose, quality as the efficient use of financial resources, and quality as the transformation of students. According to recent research conducted among academics within different geographical, cultural, and institutional contexts (

Marúm et al. 2011;

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2015;

Watty 2006), among all of the notions proposed by Harvey and Green, the latter, namely quality as transformation, is the one which elicits agreement by the majority of academic staff. This preference agrees with the fact that the quality of education when understood as the transformation of the student is most closely linked to the traditional academic values as represented in the concept of

bildung (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2015), as well as being the preferred notion by Harvey and Green themselves.

In Mexico, the most recent work on this subject has been developed by members of the research team “ECUALE” network (

Marúm et al. 2011). The research summarised in this article verified most of the conclusions of the studies of Marúm et al. with respect to teachers’ preferences for quality concepts (

Table 4), despite the fact that different methodologies and methods were used.

Firstly, it is noted that, in general, academic staff in Mexican universities operate with three different approaches or references of the meaning of quality. The first approach is the most personal and intimate of the academic community, which links the quality of education to its capacity to achieve a transformation in the students that allow them to acquire greater awareness and mastery of their own learning. The second refers to the institution, that is to say, to the objectives that have been implemented by the particular institution where the academic is employed, including academic standards. For most commercial companies, this is the main point of reference: the staff of an automobile factory, for example, has no other rules that affect them in their doing their job than those devised by their company. Conversely, at the university (as in other sectors such as medicine, for example) staff is guided by other values in addition to the performance, productivity, or strategy objectives established by the organisation. The last approach is that of the external stakeholders, including in this group the students and the institutions that employ graduates. The intimate relationship between teachers and students is an intrinsic characteristic of teaching work and, in general, of the professionalization of social services connected to the development of the welfare state (

Roiphe 2016). In this relationship, the determination of the quality of service, as well as quality control and quality assurance were always considered the responsibility of the profession. The customer had little or no input in the matter. However, over time, the extension of the idea of client to professional social services (also in higher education) has favoured a translation of these responsibilities to the consumer, whose authority to define the service as “of quality” is increasing (

Budd 2017).

It could be said that these three references represent three dimensions of educational quality that academic staff identify as separate, though to some extent compatible. It is also observed that in general, the teaching staff have a more pronounced preference for the notions of quality associated with academic references, a lesser or less widespread preference for notions associated with the academic institution, and an even lower preference for those associated with external stakeholders.

The design of the research also allows the comparison of the preferences of academic staff with those that the staff attributes to their institution. Obviously, a HEI does not have the ability to feel or express any preferences on this or any other subject. It must be understood therefore that the responses of individuals consulted was based on their observations of the policies and programs implemented within the institution, as well as on the interpretation of statements and decisions of the people in positions of responsibility. The possibility cannot be ruled out that teachers confuse the true intentions of management bodies or that they cannot adequately interpret the priorities set by the organisation in which they work. However, none of these circumstances reduce the transcendence of the fact that teachers feel that their ideas about what quality is within education are different from those that dominate the organisation in which they work.

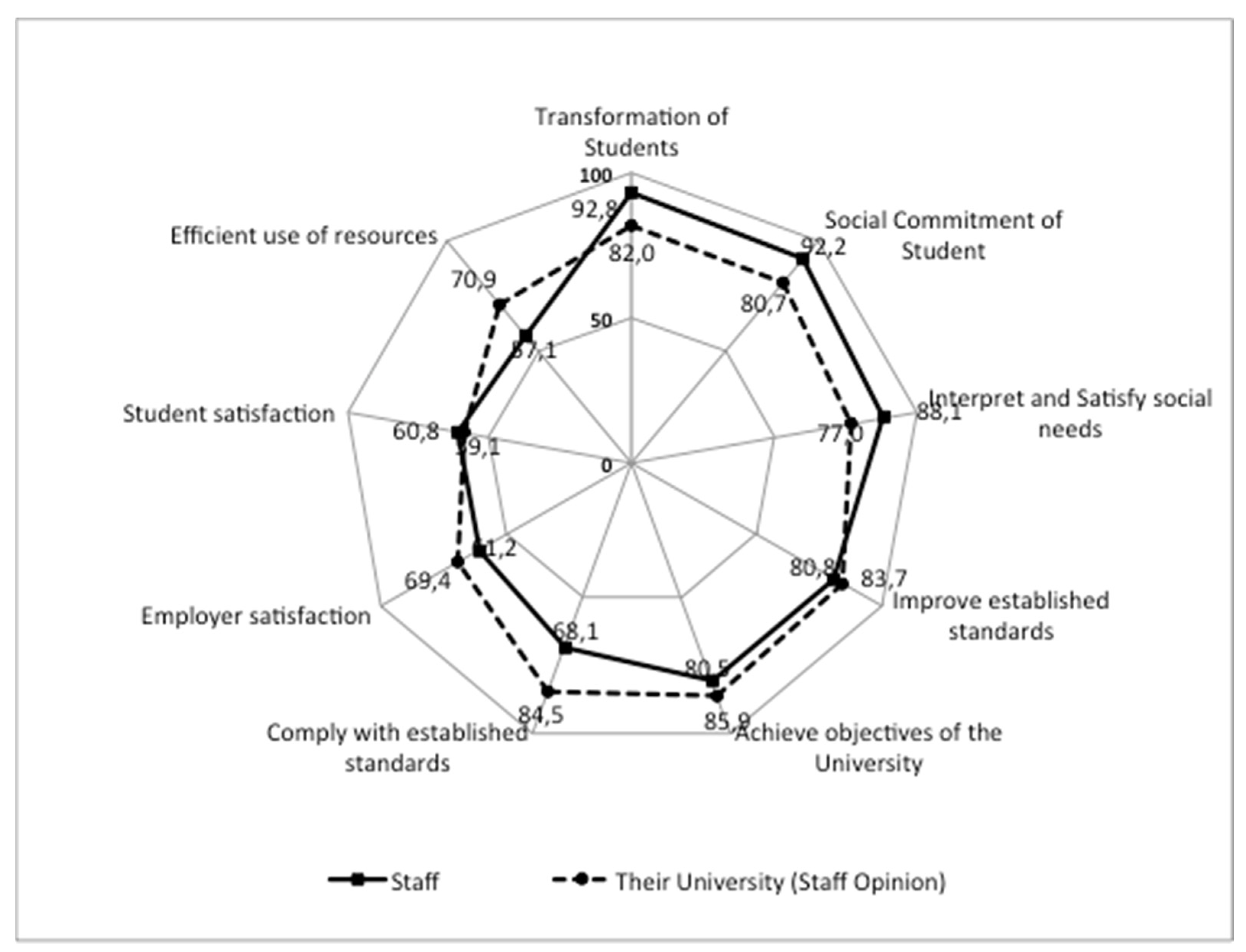

Figure 1 reflects in aggregate terms the extent of the perceived disagreement within the surveyed sample. In the figure, the notions of quality are ordered in the same way as in

Table 4, depending on the extent to which they gain support among academics. Note that, in general, academics think that their institutions defend less than themselves the ideas of quality associated with academics (the first three clockwise positions). In contrast, academic staff believes that the institutions they work for are more concerned than they are with the goals and standards set by the university. As for the quality concepts related to the satisfaction of external stakeholders, the academics believe that the institution they are employed in is relatively more concerned with the interest of employers and the efficient use of resources, that is to say in the position of stakeholders in charge of the financing of university activities.

Disagreement perceived by teachers has been calculated as a simple difference between the sum of the numerical values that reflect adherence of each individual to the operational concepts of quality associated with each dimension, and the sum of the value that reflect the extent to which the same individual believes that their university adheres to such operational concepts.

Table 3 contains the average values observed in the group of teachers consulted.

For the quality dimension closely associated with the academic reference, the value is positive. That is to say that the teaching staff is more concerned than the university itself by this dimension of the term quality. In contrast, in the other two groups (dimensions linked to objectives established by the institution and expectations of external stakeholders), the values are negative; teachers feel that their university is more aligned than themselves with these two quality dimensions.

This data can be understood as evidence that there is a conflict within Mexican higher education institutions. The conflict is not considered to be severe and it has not given rise to external protests. It is expressed only in a sense of disagreement between what the academic staff believes a HEI should be and the way it operates daily. The hypothesis on which this research is based is that this perceived disagreement causes dissatisfaction at work among the academic staff. The following section gathers some evidence in this regard.

3.2. The Influence of Quality Concepts on the Job Satisfaction of Academic Personnel

This section uses logit regressions (see section on data and methods) to check whether the disagreement perceived by academic staff influences the likelihood that dissatisfaction with their job is declared. Applied techniques allow the recognition of the individual effects of the disagreement perceived in each of the three dimensions of quality, namely

transformation of students and attention to social needs,

institutional standards and objectives, and

external stakeholder expectations (see

Table 5).

Regarding job (dis)satisfaction, two particular dimensions of work, salary and promotion opportunities, have been considered, as well as the effect on job satisfaction in general. The consideration of several dimensions of work in which staff can manifest and express different levels of satisfaction is common in the literature (

Machado-Taylor et al. 2016), although the use of simple scales to capture the level of staff satisfaction with their work in general is also backed by the literature (

Bozeman and Gaughan 2011). The literature also contains more complex scales for job satisfaction; one of the best known is the Job Descriptive Index (

Smith et al. 1969). However, this research has opted for simple scales and two particular job dimensions as described above.

The results show that, in fact, the disagreement perceived by teachers influences their job satisfaction. Disagreement in the dimension of student transformation, that is, the dimension that best fits an academics’ point of reference for quality is directly and consistently related with dissatisfaction. Teachers who consider that their university does not defend this way of understanding quality as strongly as they do are more likely to declare themselves as dissatisfied with their work as well as salary conditions and promotion opportunities available to them.

The disagreement in the other two dimensions of quality operate, when they do, in the opposite direction (note the negative sign that precedes the estimated coefficients); this means that when the individual considers that his university adheres more than they to these quality concepts, the probability of a declaration of job dissatisfaction increases.

In simple terms, these results show that when quality objectives of academic staff and university are not conceptually aligned, there is a greater risk of job dissatisfaction among staff. Academics do not like the UdeG to be less concerned than they are about the transformation of the students, which they probably interpret as the very essence of education, nor are they satisfied when the university is more concerned with the fulfilment of standards and objectives set by the UdeG itself or with the satisfaction of external stakeholders (students, employers, and public agencies in charge of part of the university financing).

It is interesting that, in general, the faculty seems to be annoyed by whichever differences are occurring between their preferences and those attributed to the university, regardless of the direction in which they occur. Teachers are, in general, more prone to dissatisfaction when their university cares less about student transformation, but also when the university cares more about other aspects such as standards or attention given to certain stakeholders. It follows from these results that academics perceive the objectives expressed as notions of quality in conflicting terms. That is, it is understood that a greater effort exerted in the pursuance of some objectives leads to less effort exerted in others. This is the only way to explain why when academic staff interpret that their institution presents an excess of zeal in matters that are not considered high in their agenda, then dissatisfaction is more likely.

The above results reinforce the theory of the political content of quality concepts. At the end of the day, the policy deals with the struggle between different groups over whose vision should prevail among the collective whole as a priority.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This article has asserted that part of the teaching staff of Mexican universities feel that their opinions about what constitutes educational quality differ from those of the institutions they work for. It is true that, as the research proposed, the university’s inclination towards concepts of quality is more of a construct of the teaching staff rather than a verifiable position; however, this does not detract from the results obtained. The preferences that teachers attribute to their institutions are derived from their interpretation of the strategies and policies implemented by management bodies, and reveals that teaching staff is not completely in agreement with the quality objectives established by the university. In other words, the results obtained constitute evidence of a latent conflict in the field of values, or, if preferred, in the priorities of the institution.

In simple terms, the conflict can be expressed as follows: some teachers interpret that their university pay excessive attention to the efficient use of resources, to the achievement of certain standards, or to meet the demand for graduates from employers, but too little to enable students to become adult citizens with a critical spirit and social conscience, and with the ability to take responsibility for their own education and life, or to achieve a leadership role for the university in effecting social change, through the interpretation of social needs and finding solutions to them.

The analysis of the teachers’ responses shows that the notions of quality are structured into three groups, each of which represents a set of objectives of HEIs, among which each one can establish an order of priority: “the transformation of students and the attention to social needs”, “the compliance with and improvement of standards and objectives of each specific HEI”, and “the attention to the demands of external stakeholders”. In turn, each of these sets of objectives can be linked to a normative reference (a “culture”, in Clark’s 1983 terminology) present in HEIs: the academic community, which presents itself as a guarantee for the preservation of the values of education (in the sense of

bildung) and research, and as a leader for society as a whole; the particular institution where each academic works, and which establishes its own objectives, rules, and operating standards; and certain external agents that benefit from the existence of higher education or contribute to its financing, and on which, ultimately, its survival depends. Expressed in the preceding terms, the debate on the concepts of quality can be interpreted as a dispute over the primacy between the above-mentioned cultural references, with many academics, maybe against the spirit of present times (

Olaskoaga-Larrauri et al. 2020), aligning more with the symbolic community of which they feel part of than with the specific organization for which they work or with the interests of their “clients” and “stakeholders”.

The research does not go into assessing the severity of the conflict, but does reveal one of its consequences: the greater the disagreement perceived by a particular teacher, the greater the likelihood of being dissatisfied with their work.

These results represent two contributions to the literature on higher education. Firstly, it provides favourable evidence to the theory of the political content of the notions of quality: the quality concepts are part of the language in which conflicting preferences are expressed about collective objectives of higher education institutions; in addition, they are also the place where frustrations of actors are deposited when their considerations and beliefs do not prevail.

Secondly, the evidence gathered suggests the necessity of updating the models that try to explain the level of job satisfaction among academic staff; it suggests that, within an organisation where values and principles are so important, the extent to which individuals see or do not see their own values reflected within the institution affects their job satisfaction, and its influence is at least as strong as that of the factors commonly represented in the most well-known explanatory models for job satisfaction (

Albert et al. 2018;

Bozeman and Gaughan 2011).

The main limitations of this research are in the methodological and practical fields. Methodologically, using the opinions of academics to identify the concepts implicit in university quality policies means adopting an excessively subjectivist approach. There are some alternatives as being researchers themselves who judge the prevailing ideas of quality in educational institutions. They could do it by reading documents (strategic plans or institutional statements) or by observing organizational changes and the spirit of quality policies. Obviously, all of these alternatives have their own drawbacks. Think, for example, of the difficulty of distinguishing between genuine commitment and mere discourse, in reading institutional declarations. In addition, in most of these alternatives, nothing could be done other than to replace the subjectivity of the academics, who respond to a survey, with that of the researchers who interpret the content of some documents or judge the sign of certain university policy decisions. In any case, it would be advisable to explore these alternatives and check if they lead to conclusions similar to those presented in this article.

From a practical point of view, this research has not been designed with the intention of identifying solutions to a problem, but of proposing a more complete diagnosis of it. As a consequence, this paper is sparing in recommendations for university managers and policy makers. It would require a completely different analysis and a distinct argumentative basis. The value of this research lies exclusively in pointing out a reality already exposed by some classics in the analysis of HEIs: that of the existence of a material and symbolic conflict between the administration and academics within HEIs. In the study conducted by Clark, for example, the conflict is perceived from the opposite shore: “Administration (…) have ample reason to see professors (…) as, at best, lacking understanding and, at worst, troublemakers and enemies” (

Clark 1983, p. 89). The present work emphasizes a specific aspect of this conflict, around the meaning that should be given to quality in the context of higher education. This aspect is not at all trivial, but firmly linked to the debate on the objectives that justify the mere existence of HEIs.