Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is producing not only epidemiological consequences on a global scale, but also political, economic, and social repercussions. The health care professionals that have been on the front lines fighting the pandemic need the support and assistance of other organizations to meet the many daily challenges. Volunteer firefighters stand out for their outreach approach and implementation of the Human2Human paradigm that has enabled them to meet the needs of the most vulnerable population that have been hit the hardest by the pandemic. This study adopts an ethnographic-action method considering Portuguese volunteer firefighters to explore the characteristics and relevance of these initiatives in areas such as combating isolation, medical assistance, containing the spread of COVID-19, and promoting public–private partnerships. The findings reveal that factors associated with altruism are central elements in the emergence of these initiatives, although some locally or nationally coordinated initiatives have been replicated in other contexts. It is also noteworthy that volunteer firefighters also present initiatives that can be fit into more than one category.

1. Introduction

The world is going through a global health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is a situation unforeseen by contemporary societies, with individual anxieties adding to the challenges facing governments and civil society. Within various sectors, such as the state, private, and non-profit sectors, in Cai et al. (2021) and Nampoothiri and Artuso (2021), several initiatives involving civil society are reported with objectives that target the general population, but that particularly impact the most vulnerable sectors of society in health or social terms.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented several challenges for organizations, requiring closures or adaptations of their business models to meet the challenges posed by the pandemic situation (Seetharaman 2020). Moreover, social organizations have reported impacts in the way they develop their activities, and they share the view that the pandemic has intensified a high set of social problems such as depression, unemployment, poverty, social inequality, and domestic violence (Gama et al. 2020; Krumer-Nevo and Refaeli 2021; Porter et al. 2021). Quantifying the impact of these problems is not consensual, but the idea has emerged that the most economically fragile and socially vulnerable countries will be the most affected. Furthermore, Wedel (2020) notes that various social actors need to think outside the box and open new paths of action that rely on social innovation.

Several organizations framed within civil society have sought to make their contribution in the sense of helping those on the front lines in the fight against COVID-19 (Arslan et al. 2022). Several projects have emerged to support society, for example, in combating social isolation, purchasing essential products, and seeking health services. These initiatives can be framed in the model proposed by Grimm et al. (2013) in which social innovation happens when the process of social entrepreneurship is successful, meaning that a new, appropriate, and creative response is found to solve a social problem. Furthermore, Almeida (2020) notes that these projects are characterized by having a strong Human2Human (H2H) component in which a humanized and close relationship is privileged. Effectively, we can assume that these projects contribute to a reconstruction of the usual environment in which human beings move and which is constituted by daily, formal, and informal interactions.

Kramer (2017) highlights the change in understanding that is taking place in recent years in terms of the relationship between organizations and their customers by using the advantages brought by communication and information technologies. Effectively, the traditional concept of the relationship established between businesses and consumers is no longer enough. A new model is emerging—the H2H—which values the humanization of the relationship between suppliers of goods and services and their customers, emphasizing people as people and investing in relationships of trust. The advantages of this approach are evident in terms of the real-time adaptation of the supply of goods and services sought by customers, i.e., the immediate adaptation to the changing needs of customers, considering the emotional component of the relationship and the benefits of structuring this relationship on a transparent basis (Kotler et al. 2021).

The approaches that have emerged in the context of understanding the exchanges between human beings within the H2H paradigm have been situated in the context of business, or exchanges involving the acquisition of goods and services for profit. We consider the initiatives of the volunteer firefighters that will be presented as going beyond the parameters that characterize business (buying and selling) on a regular basis and for-profit since they involve components and goals related to volunteering, solidarity, welfare, humanitarianism, and non-profit purposes. However, and according to Kotler et al. (2021), there is in the H2H concept a side of exploitation of the value of frugal, everyday life, and familiarity; in short, it is proximity-based on the trust built-in to ordinary interaction, and the discovery of what human beings have in common interests us here when we address the provision of services to the needy mediated by firefighters. We approach the volunteer firefighters’ initiatives as enabling an interaction that is both human and reassuring, which participates in the construction of a normality of daily human interactions, and thus sediments these peacekeepers in the collective imaginary and in collective social representations, as well as their role in the national reality.

The literature has addressed the role of firefighters in combating the challenges posed by the pandemic by placing them on the front line in responding to the needs of the population (Dagyaran et al. 2021; Jecker et al. 2020). The physical and mental health consequences of these professionals have also been addressed (Graham et al. 2021; Zolnikov and Furio 2020). However, there is a research gap in that there are no studies that explore the role and initiatives promoted by volunteer firefighters in addressing the challenges caused by the pandemic. Thus, we propose to approach in this study the case of Portuguese volunteer firefighters, and their corporations, to present activities developed in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic by the set of corporations, including their offer of services to the community in a relationship with the population that characterizes these social organizations as “soldiers of peace”. Furthermore, it aims to explore through an ethnographic study the initiatives promoted by volunteer firefighters in Portugal that enable the realization of the H2H paradigm. The presentation of new activities in the context of a pandemic demonstrates the permanent adaptation capacity of firefighters to the challenges posed by the social environment and its relevance and proximity to the most disadvantaged population.

This article is organized as follows: In the first phase, a theoretical contextualization of the processes of humanization in health is performed. In the theoretical contextualization section, the role of volunteer firefighters in Portugal is addressed. This theoretical contextualization is fundamental for the definition of the research lines that guide this study. Next, the methodology is presented, which considers the advantages and limitations of the methods adopted. After that, the results are presented and discussed. Finally, the conclusions are presented, the limitations of this study are indicated, and future lines of research are suggested.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Volunteer Firefighters and the Humanization of Healthcare during the Pandemic

Howard and Strauss (1975) sought to create a conceptualization for humanization and associate its importance with health care. This approach starts from the basic premise that human beings are producers of physiological and psychological needs, and care that is concerned with providing for them can be understood as humanized. The ideological dimension is characterized by taking three guides as references for the practice of care: the intrinsic value of human life, the irreplaceability of each human being, and that people are considered in their wholeness (Howard and Strauss 1975). Recognizing the intrinsic value of human life, regardless of status or any hierarchy, also brings into focus the debate regarding the issues of equality, equity, and the discussion about access to health care. Travelbee (1971) noted that to affirm that each person is irreplaceable is to recognize that each person possesses singularities that define a unique identity. To be insensitive to this aspect would lead to routine, standardized, and impersonal treatment. However, Asadi-Lari et al. (2004) argued that standardized care is not necessarily synonymous with dehumanization, just as differentiated treatment does not mean humanized care, either.

The importance of humanization in health, as recognized in the studies conducted by Fuente-Martos et al. (2018), Merenstein et al. (2016), and Todres et al. (2009), becomes more relevant when faced with an abrupt event on a global scale. The COVID-19 pandemic is configured as a crisis experience since it corresponds to an unexpected and disorganizing event that has caused physical and psychological suffering to the world population, and as it represents the interruption of the continuity of life, making human fragility evident and creating transformations in those who experience it. Hence, healthcare providers have encouraged humanization actions during the pandemic to offer a physical, social, and psychological welcome, such as activities focused on the experience of the patient and his/her family members (Carlucci et al. 2020). Professionals providing care tend to be involved in this process, as well, and act as humanization agents.

The large amount of information and data that have been disseminated in the media, on the Internet, and in social networks allows citizens to have knowledge about the consequences and treatments available for COVID-19. However, this information hides the real knowledge about what it means to remain for weeks, or even months, in hospitalization, both for the patient and their family. As noted in Menzies and Menzies (2020), the still poorly understood disease, combined with the large number of deaths on a global scale, causes a sense of fear and panic not only for those who are infected, but also for those accompanying that patient. Ashana and Cox (2021) pointed out that the severity of COVID-19, coupled with the distance from family members, during the period of hospitalization for treatment can be alleviated by a humane approach undertaken by the health professionals caring for the patients. Innovative practices have been developed for these patients, such as the ICU diary that allows the physician, together with the multi-professional team, to talk to the family members and share the patient’s entire clinical picture (Haruna et al. 2021). Another practice is video calls with family members, which seeks to ease the pain of isolation and separation the patient experiences when separated from their relatives (Kennedy et al. 2021).

The initiatives presented above are exclusively focused on the process of treating patients and on the relationship with their relatives. However, the humanization of health services should also include the pre-hospital phase. In this component, the role of volunteer firemen stands out as a primordial element in the relationship between the population and health services. However, the role of firefighters is much broader and includes various components of support for risk situations such as fires, floods, road accidents, accidents at work, etc. Firefighters are also required to be resourceful and quick to move, highly physically agile, and quick to react to danger. Managing the risks at hand also requires mental stamina, emotional balance, and even dispersed attention to appreciate and equate the factors present in the hazards and act accordingly (Heydari et al. 2022). The quality of interpersonal relationships to be established, whether with colleagues or with the public, especially with people in shock, requires flexibility and openness in the relationship.

It is not only organizations that are influenced by these situations—the human resources within them are also influenced. One of the major influences of crisis situations on civil protection professionals is reflected in their well-being. The well-being of the security forces and professionals who are on the front line in the fight against COVID-19 are exposed to situations of great stress and psychological complexity that may in the future have repercussions on their psychological well-being (Gómez-Galán et al. 2020; Lluch et al. 2022; Martínez-López et al. 2021; Peinado and Anderson 2020). During the pandemic, volunteer firefighters have continued to be on the front lines of rescue, transporting sick people, both urgent and non-urgent, transporting people infected with COVID-19, and responding to other emergencies that arise every day. COVID-19 has raised the bar for firefighters, increasing the number of existing occupational stressors and adding complex personal and professional challenges (McAlearney et al. 2022; Pink et al. 2021). A firefighter is seen as a credible source of information, someone who should be in possession of the correct information during occurrences and that should be able to address the rescuees’ doubts and questions. However, firefighters are also victims of information overload and have a constant obligation to manage conflicting data and identify false news. This responsibility can be an additional source of stress as firefighters themselves may have doubts and uncertainties about various aspects of the pandemic.

2.2. The Role of Portuguese Volunteer Firefighters

In Portugal, the mission of firefighters is set out in Law No. 38/2017, which defines the legal regime applicable to Portuguese firefighters in mainland Portugal. In the regime, it is specified that a volunteer firefighter is an individual who is integrated professionally or voluntarily into a fire department and has the activity of fulfilling their missions, including the protection of human lives and property in danger, through the prevention and extinction of fires and the rescue of the injured, sick, or shipwrecked, and the provision of other services provided in the internal regulations and other applicable legislation (DL38 2017). Several studies have explored the differences between professional firefighters and volunteer firefighters, and there are significant differences in relation to their dependence on municipal government entities, organizational structure, and career development (Brunet et al. 2001; Pennington et al. 2021). Volunteer fire departments are made up of volunteer firefighters integrated into a humanitarian association. As Schmidthuber and Hilgers (2019) pointed out, volunteer firefighters are primarily motivated by helping others and contributing to a common cause.

Firefighters are the frontline of the civil protection fight in an emergency and rescue, and their actions are most visible in society when fires, accidents, and/or disasters occur. Cipriano (2016) highlights that there are about 30,000 active firefighters in Portugal, of which 92% are volunteer firefighters who practice their profession in their spare time. This statistic shows that the difference in headcount between professional and volunteer firefighters is very significant. There are historical and strategic reasons that justify this large difference. In Portugal, firefighting, as an occupation, was born almost 650 years ago from associative structures that, over time, have expanded their scope of response (Cipriano 2016). This means that the country did not feel a great need to create professional firefighter structures since this associative structure responded well to the challenges posed in the country. Moreover, the financial sustainability needed to create and maintain a professional firefighter organization was another reason why the creation of more professional structures was continuously postponed (Oliveira 2016).

As is recognized in the structure of civil protection in Portugal, firefighters are a fundamental component of the response to populations and are guided by an action that is mainly planned and operationalized at the municipal/local level. According to Amaro (2013), this fact raises questions about integrated responses at the national level, with a national plan or strategy to address the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it clearly shows a particular configuration of the relationship with the local populations of each fire department, which is a relationship of a municipal scope. In fact, consulting the civil protection operating structure ANEPC (2021), its integrated system of protection and rescue operations, and its coordination structures (SIOPS 2021) may not be very useful if we intend to frame the actions of fire departments related to the pandemic in a concerted strategy at the national, or even district, level. The root of the actions of firefighters in the current pandemic context should be sought in view of the dynamics (municipal/local) of each fire department and in the altruistic essence of the volunteerism that they frame.

We can conclude that Portuguese fire departments are characterized by work of proximity to the population and are very much based on volunteering. Indeed, the characteristics of voluntary fire departments are, among other things, to belong to a humanitarian firefighters association and to be made up of firefighters on a voluntary basis. They are associations with their own legal status, which defines them as non-profit legal entities dedicated to the protection of people and property. Their missions include rescuing the injured, sick. or shipwrecked, and extinguishing fires (ISDR 2016). It makes perfect sense to list the activities carried out by firefighters in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic that, in addition to meeting their regular mission, also demonstrate initiative and the ability to adapt to new circumstances within an H2H paradigm. The population is used to the proximity of the firefighters in meeting their needs, but several projects have arisen in the current crisis and the circumstances allow for an extension of the capacity of the firefighters and their coverage (Dudman 2020).

3. Research Dimensions

The emergence of the pandemic forced us to rethink the model of the humanization of care. It was essential to meet emerging and priority needs from a hygienist and community perspective, particularly among socially vulnerable groups, both at the health and social levels. Despite becoming a global pandemic, it was necessary to readapt the procedures at the level of national, municipal, and local relief, all due to the transmissibility of this disease. The firefighters who have been on the frontline since the beginning of this pandemic were faced with the adoption of an effective and correct respiratory etiquette to prevent infection and possibly combat the spread of this disease that caused not only a psychological impact on these professionals, but also on the families and citizens who suffered a worsening condition at the socioeconomic level (Carbajal et al. 2021).

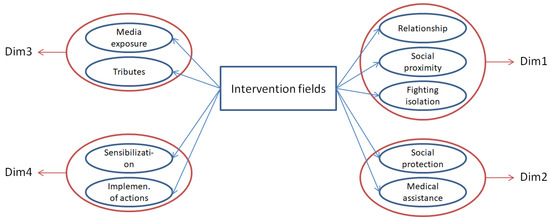

The firefighters who deal closely with the population have a privileged role and articulation with other entities, being able to collaborate in the provision of aid and assistance as with the transfer of the person infected with COVID-19 after discharge. This social proximity on the part of firefighters generated a network of solidarity on the part of the fire departments towards the community in which initiatives emerged that met the problems hitherto evident in society—problems related to isolation, social inequality (lack of assistance and protection for the most vulnerable and households in which there was a shortage of support and personal and/or financial resources, as well as essential goods), and a lack of reliable information (Long et al. 2022; Schuetz et al. 2021). The lack of response from governmental entities and the need to find solutions to problems made organizations such as volunteer firefighters seek to find innovative solutions to mitigate the social impacts of the pandemic. The initiatives launched by volunteer firefighters in Portugal can be grouped into several fields of intervention, which allowed us to build a framework based on four dimensions: (i) DIM1: relationship, social proximity, and fighting isolation; (ii) DIM2: social and/or intersectoral protection and medication assistance; (iii) DIM3: media exposure and a tribute to public–private entities involved in fighting COVID-19; and (iv) DIM4: sensibilization and implementation of actions within the scope of COVID-19 containment. These lines of intervention by volunteer firefighters during the pandemic represented in Figure 1 are aligned with the social needs of the most affected and vulnerable people during the pandemic. In Niu and Xu (2020) and Williams et al. (2021), the importance of initiatives to combat the isolation caused by COVID-19 as a way to mitigate social distancing policies to contain the spread of the pandemic is highlighted, while in Strasser et al. (2021) the role of public–private initiatives in implementing sustainable policies to combat COVID-19 is highlighted. Seddighi et al. (2021) extend this view by presenting a model based on the four Ps (i.e., public-private-people-partnerships) in which the role of governments, in reducing barriers to cooperation, is highlighted in a way that will contribute to enabling greater cooperation between the public sector, private sector, and population. The empirical data collected by Seddighi et al. (2021) show that this collaboration between these three entities is higher in times of disasters versus in normal everyday scenarios.

Figure 1.

Dimensions of volunteer firefighters’ intervention during the pandemic.

4. Materials and Methods

This study applies a qualitative methodology to understand and explore the role of volunteer firefighters in combating the challenges posed by the pandemic. Creswell and Poth (2017) argued that the potential of qualitative research should be understood in terms of the epistemological and ontological positions of this type of research, rather than by contrast with positivist foundations. Merriam and Tisdell (2015) added that qualitative research should strive to be rigorous, even though it requires relatively labor-intensive and trained researchers, and is therefore time-consuming. There are, however, no easy or mechanical solutions that can guarantee the absence of errors. In this sense, and although this issue is anchored in an epistemological debate about the nature of the knowledge produced, there are ways to avoid bias and pursue validity, which requires integrity and an exercise of judgment by the researcher, which include, among other things, triangulation, reflexivity, attention to deviant cases, and relevance (Merriam and Tisdell 2015).

The study of initiatives promoted by volunteer firefighters requires exploring the context and recognizing the complementary role of various social agents. The methods used to explore this phenomenon must therefore consider the context and the entities and people who actively participate in the construction of these projects. This study adopts a hybrid method called ethnographic-action research, which brings together characteristics specific to ethnography and action research, bringing relevant positions and tasks with regard to encouraging the description of reality, collective participation, and the production of methods of action (Bradbury 2015; Schensul and Lecompte 2016). This hybrid methodology consists of two complementary methods: ethnography and action research. Ethnography, as a method, follows some fundamental principles as highlighted by Murchison (2010) such as field research (conducted in the place where the people live and socialize), multifactorial (conducted by using two or more data collection techniques), inductive (a descriptive accumulation of detail), and holistic (the most complete picture possible of the group under study). For its part, action research contributes in three ways to achieve research objectives, according to the context described by ethnography (Klein 2012): active participation (the people who will benefit from the research participate in the research with the researchers, defining objectives, and interpreting the conclusions/results), action-based methods (the activities and experiences of the participants generate knowledge in combination with more formal methods), and action production (the research is directed to generate short-, medium-, and long-term plans, as well as ideas, initiatives, solutions, and the location of new resources and partners).

Ethnographic-action research has been primarily used in the fields of social sciences and educational sciences, wherein various stakeholders are involved (Deery 2019; Jena 2019). To mitigate the issues related to the lack of objectivity and the difficulties of generalization as realized in Schensul and Lecompte (2016), a framework consisting of four dimensions (i.e., DIM1, DIM2, DIM3, and DIM4) was used that objectively allows the lines of intervention of volunteer firefighters in times of pandemic. Four research questions are associated with the study dimensions: RQ1. What is the contribution of volunteer firefighters to the establishment of close relations with the population? RQ2. What is the relevance of voluntary fire departments to the emergence of social protection initiatives? RQ3. What is the media exposure of the voluntary fire department’s initiatives? RQ4. What is the role of the volunteer fire department to the emergence of awareness actions? Furthermore, and to increase the potential for replication of the findings of this study, multiple sources of information were used (e.g., ethnographic data, data from the Portuguese Firefighters League, and data from the national, regional, and local media). These multiple sources of information allowed for a greater coverage of the initiatives promoted by national firefighters in Portugal. The study was conducted between October 2020 and July 2021, and the study participants were involved in the field research and data interpretation processes. The national association of volunteer firefighters in Portugal was contacted to provide indications of projects to combat COVID-19. After that, the responsible individuals for each fire department were identified and contacted. The ethnographic study was carried out with 28 fire departments, the information was collected through interviews with these departments, and field research work was carried out to collect this information through interviews, field observations, and public news about these events. Information was removed from fire fighters whose initiatives were identical to others, but the initiatives that were slightly different, depending on the geographical and social context in which the fire fighters develop their activity, were kept. This approach is aligned with the principles of the ethnographic research advocated for by Jones and Smith (2017) in which it was argued that ethnographic research should be multifactorial, by using two or more complementary data collection techniques, and holistic, by providing as complete a portrait of the group under study as possible. Finally, an individual report about each identified initiative was produced.

5. Results

The initiatives carried out by the volunteer fire departments in Portugal are summarized in Table 1. The intervention categories in which volunteer fire departments played an active role are presented and the fire departments involved are described, as are the initiatives carried out by these men and women “soldiers of peace”. It should be noted that there are corporations that acted in more than one category and initiative.

Table 1.

Portuguese volunteer firefighters’ initiatives.

5.1. DIM1—Relationships, Social Closeness, and Fighting Isolation

This category included all the initiatives aimed at contacting the most vulnerable members of the public (e.g., children, the elderly, citizens with no family or neighborhood support, and those who had some comorbidities that made it impossible for them to access certain essential services).

The isolation heavily affected the elderly who were already living alone, but with the suspension of all school activities, both school and non-school, daycare centers, schools and universities, children, and adolescents were deprived of their friendships and physical and social contact, which made them more restless and confused and even led to the development of other pathologies, such as anxiety. The firefighters, in this pandemic context, brought joy to their homes with the sounding of sirens at their doors while magically chanting "Happy Birthday". This was a simple gesture that brightened up many lives that were more secluded in their space and isolated from the world around them.

5.2. DIM2—Social Protection and/or Intersectoral and Medicinal Assistance

When the state of emergency was decreed, certain rights and freedoms were suspended without the most basic human rights being called into question. The goal of these measures was to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and this is why “compulsory confinement” was imposed in certain cities. In this category, we fit the initiatives that should come from a duty of the “State”, but, given the current situation, it was necessary to join forces to meet the needs that presented themselves along the way with health, social and economic professionals, and municipalities/local authorities. Thus, firefighters, as they are also agents of support who help and act not only in the prevention phase, but also in the problem itself, were central to the initiatives those in this category carried out in times of crisis, acting in response to the crisis that the country was going through.

We found that the actions described in this category encompass collaborative partnerships with several civil society entities, as advocated by Ziegler (2017), in which they interacted in a network of constant proximity to ensure that nothing was missing for those who already had little or were unable to do themselves due to their isolation. These initiatives consisted of the transportation of free medication from pharmacies and/or hospitals to the homes of people with comorbidities, chronic diseases, or oncological diseases. We also observed that there were fire departments that worked on more than one front, i.e., who provided more than one type of support, namely, transporting food products, personal hygiene and cleaning products, and other essential goods such as medication.

5.3. DIM3—Tribute to the Public–Private Entities Involved in the Fight against COVID-19

Intending to ensure the safety and health of all operatives, fire departments had to define internal plans and measures. There was a system of rotation of operatives and, in other cases, only certain elements dealt with medical emergencies because if a team was contaminated with COVID-19, there was another team in reserve. This situation led many of these men and women firefighters, as a precaution, to not go home and instead remain at the fire station for days, or months, in some cases, so that their families would also be protected since they were transporting patients suspected or even infected with COVID-19 to hospital units.

In this sense, many initiatives were seen and visualized in the media towards health professionals. However, there was little visibility for fire departments. We know that many were applauded, but this is not always enough since we have to show the reality of firefighters during times of crisis. Therefore, in order to show the other side of rescue, the separation and suffering (of firefighters from their support network), and the other (positive) side of the pride of these professionals (continuing to do what they love the most, following, to the letter, the motto “Life for Life”), the television media carried reports and or interviews to not only show the reality, but also to honor them for their faith, perseverance, courage, and commitment to such a noble and generous cause.

This category also includes initiatives carried out by the Fire Department and other agents of the community who played a preponderant role in supporting, helping, and showing solidarity with the most vulnerable groups in the whole pandemic context.

5.4. DIM4—Implementation of Actions within the Scope of COVID-19 Containment

The pandemic took everyone by surprise, including health and emergency professionals, and it raised awareness about the need to rethink and apply new, more extreme and rigorous self-protection measures to limit jeopardizing their health status or that of others with whom they deal on a daily basis.

In this context, it was indeed pertinent to create contingency plans that aimed to guarantee the population the best conditions to act on with the most fragile and vulnerable members of the public, as well as the creation of isolation rooms for suspected cases of COVID-19 that presented symptoms such as fever, cough, and/or breathing difficulty.

In this sense, actions were also taken to clean the streets and common spaces where there was a greater proliferation of passersby. For pandemic control, awareness campaigns and actions were carried out with the objective of informing, sensitizing, and “co-responsibilizing” the population so that they would not stay too long in places where they could lead gatherings and, therefore, be affected by the pandemic. These awareness-raising actions were also intended to prevent risky behaviors and replace feelings of fear and danger with more positive ones regarding safety.

The campaigns carried out by firefighters have gone from a micro level of intervention to a macro level in which these actions are no longer, in some cases, only at the local level. With the power of new technology, these campaigns have reached other target audiences (i.e., large communities and across borders). Firefighters and agents that act in crisis, health, and emergency areas have a fundamental role in finding strategies to reduce the proliferation of infection by COVID-19. It is noteworthy that many corporations with few resources have done (and continue to do) their best, for the sake of sick and healthy citizens, to safeguard the social and common welfare.

6. Discussion

Intervening in the field of a medical emergency context was yet another challenge posed to these operatives. Portuguese volunteer firefighters acquired a multifaceted role in the sense that in addition to their daily duties, they also acted on other fronts to support the population and combat COVID-19. Several problems stood out in the lives of many citizens who, due to this pandemic, became unemployed, with scarce resources, which consequently led to an increase and greater visibility of other social problems such as poverty. Results from empirical studies show that socially vulnerable populations are more likely to be negatively affected during emergencies (Cutter et al. 2010; Flanagan et al. 2011; O’Brien et al. 2006). This evidence was confirmed during the pandemic, as well. Whitehead et al. (2021) reported that the impact of COVID-19 is greatest on minorities and disadvantaged groups, indicating that the effects of the pandemic were not uniform throughout the population. In addition, the UN (2021) reported that the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is negatively affecting the lower-income fringe of the population, while benefiting those who already receive good salaries. Additionally, in the labor market, the pandemic has most strongly affected the lower-skilled fringe of the population, who are most at risk of losing their jobs (UN 2021). Therefore, supporting these most vulnerable groups was one of the missions in which the intervention of volunteer firefighters stood out the most.

It is important to point out that firefighters have also suffered in the fight against this pandemic because this situation has brought many changes and new demands. The fundamental role of volunteer firemen, due to the country’s geographical location and extensive forested area, is centered on fighting fires. However, other functions are included in this work. Monteiro (2020) noted, “to the firefighters’ work, new demands, new fears and, therefore, some psychological weaknesses”. In this context, the National Civil Protection Authority (ANEPC) created a psychosocial support line that aimed to “try to respond to the doubts and anxieties of firefighters facing COVID-19” (Monteiro 2020) because many firefighters were infected with this disease. Monteiro (2020) added that “There are situations in the rescue situation where the risk of infection is quite high. This causes levels of anxiety and nervousness that are much higher than normal practice in fire departments”. Additionally, the study conducted by Navarro et al. (2021) identified that firefighters who breathe smoke from the frontline of forest fires suffer from a higher risk of aggravation with the COVID-19 disease, with potentially lethal effects. The physical and mental health of health care workers is of strong concern, with this group being more vulnerable to mental health problems (Martín et al. 2021; Ongaro et al. 2022). This group also includes volunteer firefighters whose work has had to be divided between their families and serving their country. Moreover, this is compounded by the fear of contagion from family members, which leads to feelings of guilt, in some situations, when contagion has indeed occurred. The risk is increased in those who have been quarantined and then return to work (Ankit et al. 2020).

We know that these professionals have further developed their crisis intervention skills. Luecke and Barton (2004) defined that a crisis situation occurs when “a change—either sudden or evolving—that results in an urgent problem that must be addressed immediately.” This definition is broad and does not specify the scenarios in which a crisis can occur. However, the definition provided by the Macmillan Dictionary (2021) specifies several crisis scenarios motivated by an abrupt negative occurrence in the financial, economic, and political arena. The same source adds that crises brought about by events in health included two complementary definitions in this area: “a dangerous situation in someone’s personal or professional life when something could fail” and “a time when a disease starts to get better or worse very suddenly” (Macmillan Dictionary 2021). It is particularly in the context of healthcare where the role of volunteer firefighters has stood out. In addition to their mission of transporting patients to hospital units, volunteer firefighters had a mission of proximity to their communities.

Throughout this study, we verified that there were several initiatives that firefighters developed within the community, and we also experienced the solidarity of firefighters with many entities, institutions, and groups of ordinary citizens who created a network of partnerships and interrelationships so that basic necessities (e.g., medicines, food, and personal hygiene and cleaning products, among others) could reach the most vulnerable people who were mostly isolated (with comorbidities). The networked involvement of volunteer fire departments with civil protection agents meant that local initiatives could be replicated in a national context, thus increasing the number of people who benefited from these projects. This vision is aligned with the proposal of Lehtola and Stahle (2014) in which it was argued that social innovations should not be restricted to the inclusion of new technologies but should propose integrative solutions that foster reform and renewal of the whole society. The collaborative networking of fire departments with other organizations operating in other dimensions, scales, or sectors is fundamental to achieving social objectives. As Dionisio and Vargas (2022) pointed out, it is necessary to understand that the buy-in of the market and desired partners is as fundamental to ensuring the success of an initiative as the capabilities of the organization or project itself are, in terms of management, funds, leadership, governance, public relations, and flexibility. This implies the emergence of a cooperative mentality that goes beyond the limits of an area of intervention, scale, or economic sector. It is only when organizations go outside their walls to find ways to engage the collaboration of other entities that effective social change can be promoted.

The concept of H2H was evident in the volunteer firefighters’ and community/civil society’s outreach. The empathy, compassion, and authenticity towards others without wanting anything in return was fundamental so that, in the face of adversity, unity remained among all (i.e., firefighters and the local community), and the needs of the most vulnerable were met with excellence and selflessness and the common welfare was achieved. The findings allow extending the study conducted by Almeida (2020) in which the role of civil society, business, and local authorities in promoting solutions to combat the challenges posed by the pandemic was highlighted. Volunteer firefighters in Portugal were also a key part of the response mechanisms that emerged informally and were motivated by the response to a social emergency. During the pandemic, their relevance in society became more evident. This view is in line with the work done by Bundy et al. (2017) in which it was mentioned that optimal management of a crisis can bring positive recognition and added value to stakeholders, while poorly managed crises can short-circuit organizational viability. Furthermore, the measures to contain the spread of the pandemic based on social distancing contributed to the emergence of feelings of social isolation, especially among older populations and/or those who fell into poverty and social exclusion. Rosedale (2007) noted that loneliness is a subjective feeling and is related to the absence of contact and the feeling of belonging or the feeling of being isolated. This feeling of loneliness, as reported in Banerjee and Rai (2020) and Clair et al. (2021), interfered with people’s quality of life during the pandemic.

7. Conclusions

The H2H paradigm that emerged to complement traditional business approaches and to value the humanization of the relationship between suppliers, companies, and customers has, in the context of the pandemic, taken on new contours. The pandemic has contributed to deep awareness and reflection on the value of life and the opportunity to live in unique and unrepeatable times in time and space, in which it is worth living, despite the different and asymmetric social contexts. Portugal has been hit hard by several crises over recent decades, which makes its population more resilient and receptive to helping the most vulnerable members of its society. A demonstration of this ability was given by the volunteer firefighters who, supported by the H2H paradigm, developed initiatives with high human interaction that were, above all, directed to the most vulnerable members of the population who were, consequently, the most strongly affected by the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, volunteer firefighters have assumed the dual role of supporting their families and society, in general. They were a key element, together with other emergency forces and hospital centers, in meeting the challenges posed by the pandemic. However, the challenges were not only limited to the physical component. The social role of firefighters deserves to be widely recognized and this study has allowed us to understand how the different initiatives promoted by volunteer firefighters in Portugal were implemented in practice and replicated among the various corporations. It also allowed us to understand how the firefighters functioned as social instruments to get closer to the population, especially to those citizens in more vulnerable situations.

This study offers both theoretical and practical contributions. In the conceptual dimension, this study explores the initiatives promoted by volunteer firefighters in Portugal considering a framework consisting of four dimensions, including the establishment of proximity relationships to combat isolation, social protection and medication assistance, the relationship with public–private entities, and the implementation of actions within the scope of COVID-19 containment, which includes pandemic control practices, awareness-raising campaigns and actions, and other socially relevant initiatives. In the practical dimension, the results of this study are relevant for understanding the relevance of volunteer firefighters in crisis contexts that greatly extend their main missions, such as firefighting. This study presents some limitations that are relevant to address. First, it was not intended to make a systematic review of these movements and a quantitative analysis of their geographical distributions. Difficulties arise in replicating the results to other geographic contexts and civil protection organizations, given the ethnographic approach adopted, which for reasons of proximity included mostly volunteer fire departments in the north and center of the country. Furthermore, the benefits of these actions for their communities were not explored qualitatively or quantitatively. In this sense, and as future work, it is suggested that a study be carried out to understand the effects of these initiatives on their communities through the adoption of mixed methods. It is also recommended that this study can be applied and explored in other countries more strongly affected by the pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A., J.M. and A.P.; methodology, A.P.; validation, F.A. and J.M.; formal analysis, F.A.; investigation, F.A., J.M. and A.P. writing—original draft preparation, F.A.; writing—review and editing, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Almeida, Fernando. 2020. The Concept of Human2Human in the Response to COVID-19. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences 9: 129–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, António. 2013. O Socorro em Portugal: Mudança de Perspetiva. Revista de Direito e Segurança 1: 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- ANEPC. 2021. Autoridade Nacional de Emergência e Proteção Civil. Available online: http://www.prociv.pt/pt-pt/Paginas/default.aspx (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Ankit, Jain, Krishna Bodicherla, Qasim Raza, and Kamal K. Sahu. 2020. Impact on mental health by “Living in Isolation and Quarantine” during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 9: 5415–18. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, Ahmad, Samppa Kamara, Ismail Golgeci, and Shlomo Tarba. 2022. Civil society organisations’ management dynamics and social value creation in the post-conflict volatile contexts pre and during COVID-19. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 30: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Lari, Mohsen, Marcello Tamburini, and David Gray. 2004. Patients’ needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: Towards a comprehensive model. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashana, Deepshikha, and Christopher Cox. 2021. Providing Family-Centered Intensive Care Unit Care Without Family Presence—Human Connection in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA Network Open 4: e2113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Debanjan, and Mayank Rai. 2020. Social isolation in COVID-19: The impact of loneliness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66: 525–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, Hilary. 2015. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, Alexia, Larry DeBoer, and Kevin McNamara. 2001. Community Choice between Volunteer and Professional Fire Departments. Nonprofit and Volunteer Sector Quarterly 30: 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, Jonathan, Michael Pfarrer, Cole Short, and Timothy Coombs. 2017. Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, Interpretation, and Research Development. Journal of Management 43: 1661–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, Qihai, Aya Okada, Bok Jeong, and Sung-Ju Kim. 2021. Civil Society Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Study of China, Japan, and South Korea. China Review 21: 107–37. [Google Scholar]

- Carbajal, Jose, Warren Ponder, James Whitworth, Donna L. Schuman, and Jeanine M. Galusha. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on first responders’ resilience and attachment. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, Matilde, Lucia Federica Carpagnano, Lidia Dalfino, Salvatore Grasso, and Giovanni Migliore. 2020. Stand by me 2.0. Visits by family members at COVID-19 time. Acta Biomedica 91: 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano, Rita. 2016. Como é que é ser bombeiro em Portugal? Available online: https://observador.pt/2016/08/11/como-e-que-e-ser-bombeiro-em-portugal/ (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Clair, Ruta, Maya Gordon, Matthew Kroon, and Carolyn Reilly. 2021. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, Susan L., Christopher G. Burton, and Christopher T. Emrich. 2010. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 7: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagyaran, Ilkay, Signe Stelling Risom, Selina Kikkenborg Berg, Ida Elisabeth Højskov, Malin Heiden, Camilla Bernild, Signe Westh Christensen, and Malene Missel. 2021. Like soldiers on the front—A qualitative study understanding the frontline healthcare professionals’ experience of treating and caring for patients with COVID-19. BMC Health Services Research 21: 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, Claire. 2019. An ethnographic action research project: National curriculum, historical learning and a culturally diverse Melbourne primary school. Ethnography and Education 14: 311–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, Marcelo, and Eduardo R. Vargas. 2022. Integrating Corporate Social Innovations and cross-collaboration: An empirical study. Journal of Business Research 139: 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DL38. 2017. Lei n.º 38/2017. Available online: https://data.dre.pt/eli/lei/38/2017/06/02/p/dre/pt/html (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Dudman, Jane. ‘This Is Beyond Anything We Have Ever Seen’: The Fire Crews Tackling COVID-19. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/22/fire-crews-tackling-covid-19 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Flanagan, Barry E., Edward W. Gregory, Elaine J Hallisey, Janet L. Heitgerd, and Brian Lewis. 2011. A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 8: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente-Martos, Carmen, M. Rojas-Amezcua, M. R. Gómez-Espejo, P. Lara-Aguayo, E. Morán-Fernandez, and E. Aguilar-Alonso. 2018. Humanization in healthcare arises from the need for a holistic approach to illness. Medicina Intensiva 42: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, Ana, Ana Rita Pedro, Maria João Leote de Carvalho, Ana Esteves Guerreiro, Vera Duarte, Jorge Quintas, Andreia Matias, Ines Keygnaert, and Sónia Dias. 2020. Domestic Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Portugal. Portuguese Journal of Public Health 38: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, José, Cristina Lázaro-Pérez, Jose Á. Martínez-López, and María d. M. Fernández-Martínez. 2020. Burnout in Spanish Security Forces during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, Elliot L., Saeed Khaja, Alberto Caban-Martinez J., and Denise L. Smith. 2021. Firefighters and COVID-19: An Occupational Health Perspective. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63: 556–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, Robert, Christopher Fox, Susan Baines, and Kevin Albertson. 2013. Social innovation, an answer to contemporary societal challenges? Locating the concept in theory and practice. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 26: 436–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, Junpei, Hiroomi Tatsumi, Satoshi Kazuma, Hiromitsu Kuroda, Yuya Goto, Wakiko Aisaka, Hirofumi Terada, and Yoshiki Masuda. 2021. Using an ICU Diary to Communicate With Family Members of COVID-19 Patients in ICU: A Case Report. Journal of Patient Experience 8: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, Ahad, Abbas Ostadtaghizadeh, Ali Ardalan, Abbas Ebadi, Iraj Mohammadfam, and Davoud Khorasani-Zavareh. 2022. Exploring the criteria and factors affecting firefighters’ resilience: A qualitative study. Chinese Journal of Traumatology 25: 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, Jan, and Anselm L. Strauss. 1975. Humanizing Health Care. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- ISDR. 2016. The Structure, Role and Mandate of Civil Protection in Disaster Risk Reduction for South Eastern Europe. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/9346_Europe.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Jecker, Nancy S., Aaron Wightman, and Douglas Diekema. 2020. Prioritizing Frontline Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The American Journal of Bioethics 20: 128–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, Aniruddha. 2019. Ethnographic Action Research in Community Media Studies: Understanding the Approach. Community Communication 1: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Janice, and Joanna Smith. 2017. Ethnography: Challenges and opportunities. Evidence-Based Nursing 20: 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, Niki, Alexis Steinberg, Robert Arnold, Ankur Doshi, Douglas White, Will DeLair, Karen Nigra, and Jonathan Elmer. 2021. Perspectives on Telephone and Video Communication in the Intensive Care Unit during COVID-19. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 18: 838–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Sheri. 2012. Action Research Methods: Plain and Simple. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, Philip, Waldemar Pfoertsch, and Uwe Sponholz. 2021. H2H Marketing: Putting Trust add Brand in Strategic Management Focus. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 20: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Bryan. 2017. There Is No B2B or B2C: It’s Human to Human #H2H. San Jose: Substantium. [Google Scholar]

- Krumer-Nevo, Michal, and Tehila Refaeli. 2021. COVID-19: A poverty-aware perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 91: 423–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtola, Ville, and Pirjo Stahle. 2014. Societal innovation at the interface of the state and civil society. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 27: 152–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch, Cristina, Laura Galiana, Pablo Doménech, and Noemí Sansó. 2022. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Compassion Satisfaction in Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review of the Literature Published during the First Year of the Pandemic. Healthcare 10: 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Emily, Susan Patterson, Karen Maxwell, Carolyn Blake, Raquel B. Pérez, Ruth Lewis, Mark McCann, Julie Riddell, Kathryn Skivington, Rachel Wilson-Lowe, and et al. 2022. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 76: 128–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecke, Richard, and Larry Barton. 2004. Crisis Management: Master the Skills to Prevent Disasters. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan Dictionary. 2021. Crisis—Definitions and Synonyms. Available online: https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/crisis (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Martín, Josune, Ángel Padierna, Ane Villanueva, and José M. Quintana. 2021. Evaluation of the mental health of health professionals in the COVID-19 era. What mental health conditions are our health care workers facing in the new wave of coronavirus? The International Journal of Clinical Practice 75: e14607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, José A., Cristina Lázaro-Pérez, and José Gómez-Galán. 2021. Predictors of Burnout in Social Workers: The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Scenario for Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlearney, Ann S., Alice A. Gaughan, Sarah R. MacEwan, Megan E. Gregory, Laura J. Rush, Jaclyn Volney, and Ashish R. Panchal. 2022. Pandemic Experience of First Responders: Fear, Frustration, and Stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, Rachel E., and Ross G. Menzies. 2020. Death anxiety in the time of COVID-19: Theoretical explanations and clinical implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapist 13: e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenstein, Joel, Jonathan Han, Jennifer Middleton, Paul Gross, and Jack Coulehan. 2016. The Human Side of Medicine. New York: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Sharan, and Elizabeth Tisdell. 2015. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, Liliana. 2020. COVID-19 e Stress. Bombeiros já têm Linha de Apoio Psicossocial. Available online: https://rr.sapo.pt/noticia/pais/2020/04/07/covid-19-e-stress-bombeiros-ja-tem-linha-de-apoio-psicossocial/188404/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Murchison, Julian. 2010. Ethnography Essentials: Designing, Conducting, and Presenting Your Research. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Nampoothiri, Niranjan J., and Filippo Artuso. 2021. Civil Society’s Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019: Patterns from Two Hundred Case Studies of Emergent Agency. Journal of Creative Communications 16: 203–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, Kathleen, Kathleen Clark, Daniel Hardt, Colleen Reid, Peter Lahm, Joseph Domitrovich, Corey Butler, and John Balmes. 2021. Wildland firefighter exposure to smoke and COVID-19: A new risk on the fire line. Science of the Total Environment 760: 144296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Yan, and Fujie Xu. 2020. Deciphering the power of isolation in controlling COVID-19 outbreaks. The Lancet Global Health 8: 452–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, Geoff, Phil O’Keefe, Joanne Rose, and Ben Wisner. 2006. Climate change and disaster management. Disasters 30: 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, Vítor. 2016. Volunteering in Firefighters in Portugal and Brazil. Direito, Segurança e Democracia 44: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ongaro, Juliana, Tais Lanes, Flávia Barcellos, Daiane Pai, Juliana Tavares, and Tania S. Magnago. 2022. Health professionals’ mental health during COVID-19 pandemic. ABCS Health Sciences 47: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peinado, Micaela, and Kelly N. Anderson. 2020. Reducing social worker burnout during COVID-19. International Social Work 63: 757–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, Michelle L., Megan Cardenas, Katherine Nesbitt, Elizabeth Coe, Nathan Kimbrel, Rose Zimering, and Suzy Gulliver. 2021. Career versus volunteer firefighters: Differences in perceived availability and barriers to behavioral health care. Psychological Services, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pink, Jennifer, Nicola S. Gray, Chris O’Connor, James R. Knowles, Nicola J. Simkiss, and Robert J. Snowden. 2021. Psychological distress and resilience in first responders and health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 94: 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, Catherine, Marta Favara, Annina Hittmeyer, Douglas Scott, Alan S. Jiménez, Revathi Ellanki, Tassew Woldehanna, Le T. Duc, Michelle G. Graske, and Alan Stein. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression symptoms of young people in the global south: Evidence from a four-country cohort study. BMJ Open 11: e049653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosedale, Mary. 2007. Loneliness: An Exploration of Meaning. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 13: 201–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schensul, Jean, and Margaret Lecompte. 2016. Ethnography in Action: A Mixed Methods Approach. Lanham: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidthuber, Lisa, and Dennis Hilgers. 2019. From Fellowship to Stewardship? Explaining Extra-Role Behavior of Volunteer Firefighters. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Volunteer and Nonprofit Organizations 30: 175–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuetz, Sebastian W., Tracy A. Sykes, and Viswanath Venkatesh. 2021. Combating COVID-19 fake news on social media through fact checking: Antecedents and consequences. European Journal of Information System 30: 376–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddighi, Hamed, Sadegh Seddighi, Ibrahim Salmani, and Mehrab S. Sedeh. 2021. Public-Private-People Partnerships (4P) for Improving the Response to COVID-19 in Iran. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 15: 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seetharaman, Priya. 2020. Business models shifts: Impact of Covid-19. International Journal of Information Management 54: 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIOPS. 2021. Sistema Integrado de Operações de Proteção e Socorro. Available online: http://www.prociv.pt/pt-pt/PROTECAOCIVIL/SISTEMAPROTECAOCIVIL/SIOPS/Paginas/default.aspx (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Strasser, Sheryl, Christine Stauber, Ritu Shrivastava, Patricia Riley, and Karen O’Quin. 2021. Collective insights of public-private partnership impacts and sustainability: A qualitative analysis. PLoS ONE 16: e0254495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todres, Les, Kathleen T. Galvin, and Immy Holloway. 2009. The humanization of healthcare: A value framework for qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 4: 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travelbee, Joyce. 1971. Interpersonal Aspects of Nursing. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2021. With Extreme Poverty Rising Amid COVID-19 Pandemic, More Action Key to Ending Vicious Cycle in Conflict-Affected, Fragile Countries, Top Officials Tell Security Council. Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sc14405.doc.htm (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Wedel, Marco. 2020. Social change and innovation for times of crises. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 33: 277–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, Margaret, David Taylor-Robinson, and Ben Barr. 2021. Poverty, health, and COVID-19. BMJ 372: n376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Christopher, Adam Townson, Milan Kapur, Alice Ferreira, Rebecca Nunh, Julieta Galante, Veronica Phillips, Sarah Gentry, and Juliet Usher-Smith. 2021. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness during COVID-19 physical distancing measures: A rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE 16: e0247139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Rafael. 2017. Social innovation as a collaborative concept. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 30: 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolnikov, Tara R., and Frances Furio. 2020. Stigma on first responders during COVID-19. Stigma and Health 5: 375–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).