Health and Environment Conscious Consumer Attitudes: Generation Z Segment Personas According to the LOHAS Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

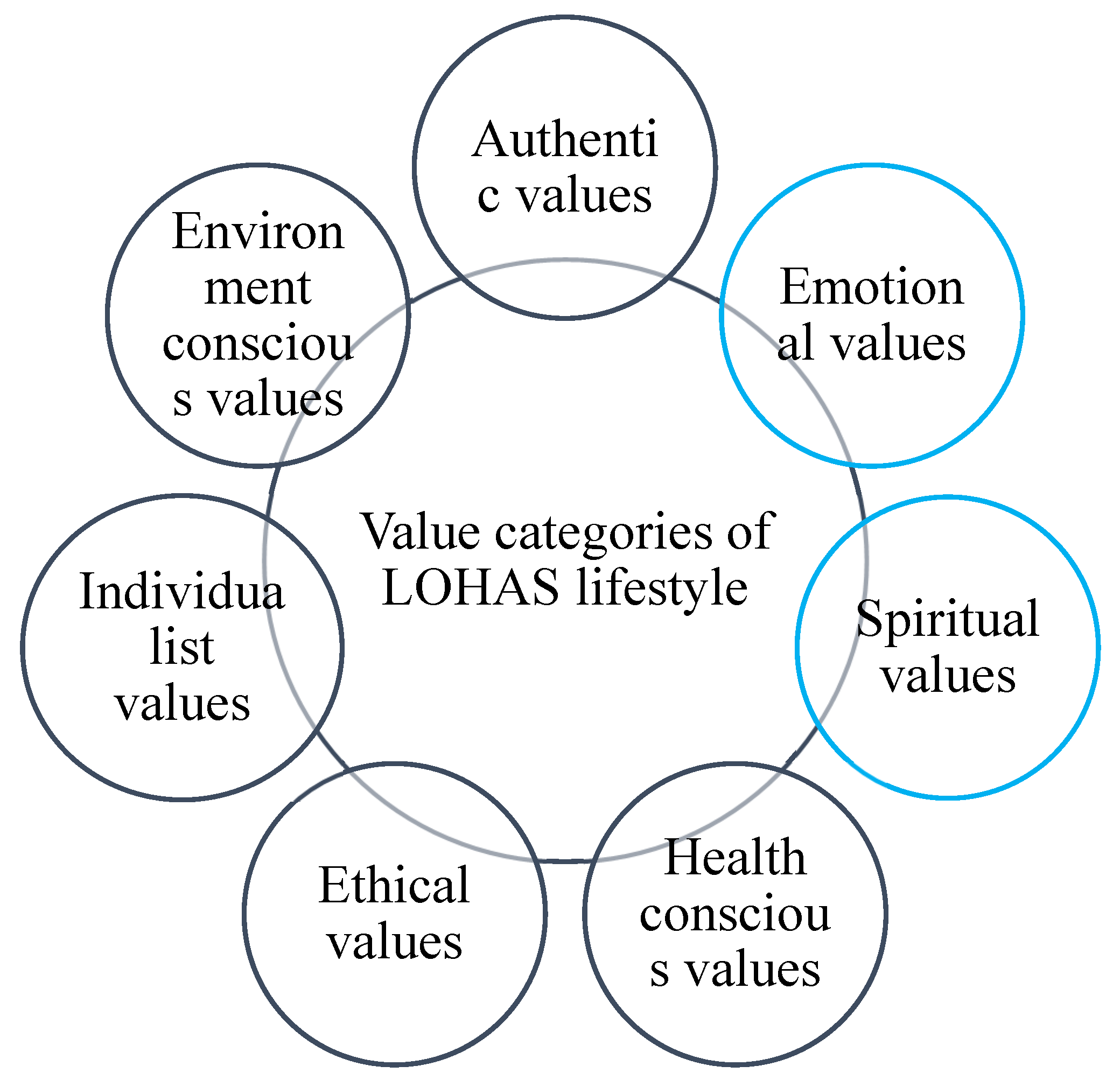

2.1. The LOHAS Model and the Key Criteria of LOHAS Consumers

2.2. Generation Z as LOHAS Consumers

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of the Descriptive Statistics of the LOHAS Scale Elements

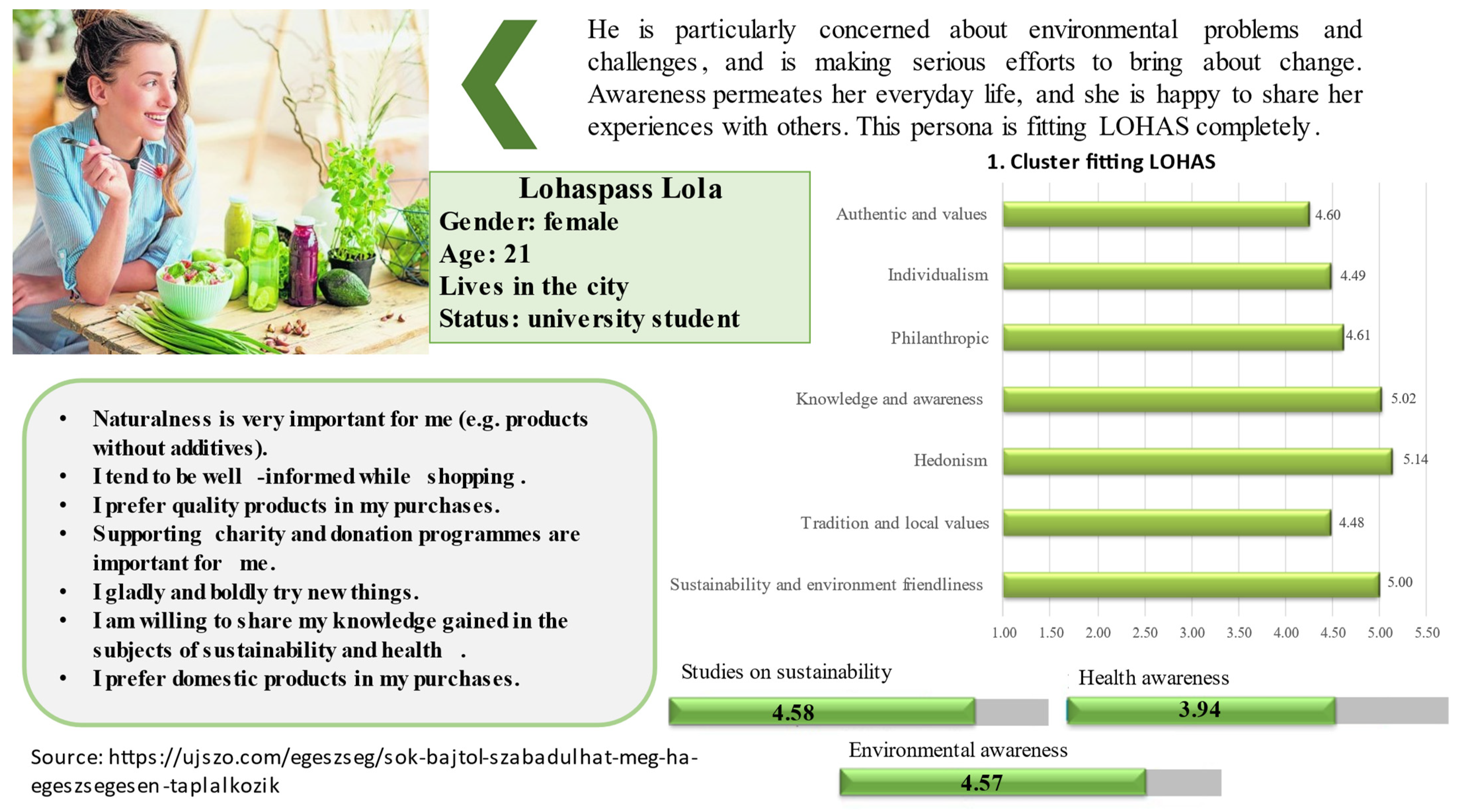

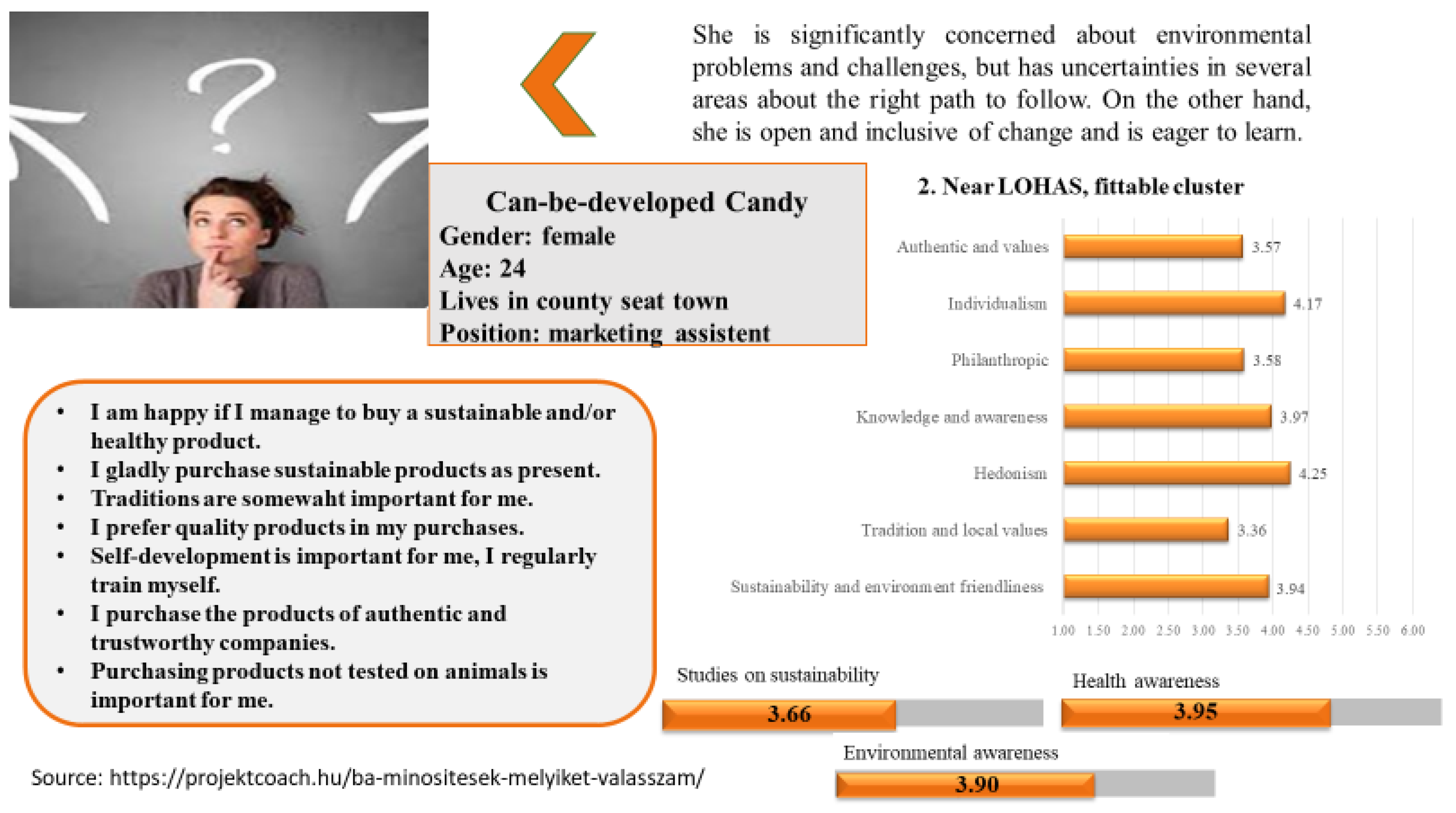

3.2. Characteristics of the Segments

- I gladly purchase sustainable and responsible products at present (mean = 5.49; median = 6.00).

- Naturalness is very important to me (e.g., products without additives) (mean = 5.30; median = 5.00).

- I am open to the latest technologies (mean = 5.29; median = 6.00).

- I tend to amplify negative news (mean = 2.97; median = 3.00).

- I tend to follow trends (mean = 3.25; median = 3.00).

- I prefer branded products when making purchases (mean = 3.33; median = 4.00)

- I am open to the latest technologies (mean = 4.72; median = 5.00).

- I gladly purchase sustainable and responsible products at present (mean = 4.56; median = 4.50).

- I gladly and boldly try new things (mean = 4.39; median = 4.50).

- Purchasing products not tested on animals is important to me (mean = 4.39; median = 4.00).

- I tend to amplify negative news (mean = 2.70; median = 3.00).

- I consciously look for the trademarks of origin and quality on the products (mean = 2.80; median = 3.00).

- I am willing to undertake voluntary work (mean = 3.03; median = 3.00).

- I am open to the latest technologies (mean = 4.13; median = 4.00).

- I gladly and boldly try new things (mean = 3.97; median = 4.00).

- I prefer high quality products (mean = 3.84; median = 4.00).

- I consciously look for the trademarks of origin and quality on the products (mean = 1.85; median = 2.00)

- I am willing to pay a higher price for sustainable and environmentally conscious products (mean = 1.90; median = 2.00).

- I am willing to undertake voluntary work (mean = 2.17; median = 2.00)

- consumer attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control are significant determining factors of the sustainable consumer behaviour of consumers (Matharu et al. 2020;)

- numerous studies investigating how individuals’ attitudes and subjective norms influence their purchase intention toward apparel products (Belleau et al. 2007; Marcketti and Shelley 2009; Yan et al. 2010; Yoh et al. 2003; Chi and Kilduff 2011; Pícha and Navrátil 2019).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bacher, János. 2020. LOHAS Fogyasztók. Akiknek a Zöld már Nem egy szín, Hanem életstílus. Paper Presented at Zöld Marketing Konferencia. Available online: https://markamonitor.hu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Z%C3%B6ld_Marketing_Konferencia_20200130_Bacher_Janos_LOHAS.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Bakewell, Cathy, and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell. 2004. Male Consumer Decision-Making Styles. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 14: 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsa-Budai, Nikolett, and Zoltán Szakály. 2018. A fenntartható értékrend vizsgálata a debreceni egyetemisták körében. Táplálkozásmarketing 5: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleau, Bonnie D., Teresa A. Summers, Yingjiao Xu, and Raul Pinel. 2007. Theory of reasoned action: Purchase intention of young consumers. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 25: 244–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brünger, Franziska. 2016. Zielgruppengerechtes Marketing: Strategien und Maßnahmen für Lohas [Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien]. Available online: https://monami.hs-mittweida.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/8632/file/BA_Br%c3%bcnger,Franziska.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Buerke, Anja, T. Straatmann, Nick Lin-Hi, and Karsten Müller. 2017. Consumer awareness and sustainability-focused value orientation as motivating factors of responsible consumer behavior. Review of Managerial Science 11: 959–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Ching-Chan, Ya-Yuan Chang, Ming-Chun Tsai, Cheng-Ta Chen, and Yu-Chun Tseng. 2019. An evaluation instrument and strategy implications of service attributes in LOHAS restaurants. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 31: 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, Iksha, and Avneet Kaur. 2022. Development of a convenient, nutritious ready to cook packaged product using millets with a batch scale process development for a small-scale enterprise. Journal of Food Science and Technology 59: 488–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Ting, and Peter P. D. Kilduff. 2011. Understanding consumer perceived value of casual sportswear: An empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 18: 422–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Sooyeon, and Richard A. Feinberg. 2021. The LOHAS (Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability) Scale Development and Validation. Sustainability 13: 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Chia-Jung, Kuo-Sheng Chen, and Yueh-Ying Wang. 2012. Green practices in the restaurant industry from an innovation adoption perspective: Evidence from Taiwan. International Journal of Hospitality Management 31: 703–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computer Generated Solutions (CGS). 2019. Sustainability Is Critical for Consumer Brands. Available online: https://www.cgsinc.com/sites/default/files/media/resources/pdf/CGS_2019_Retail_Sustainability_infographic.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Du, Chung Thi, Thu Thi Ngu, Thi Van Tran, and Ngoc Bich Tram Nguyen. 2021. Consumption Value, Consumer Innovativeness and New Product Adoption: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 8: 1275–86. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Tracy, and Francisca Hoefel. 2018. ‘True Gen’: Generation Z Characteristics and Its Implications for Companies|McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Gangadharbatla, Harsha, Christopher Vardeman, and Danielle Quichocho. 2020. Investigating the reception of broad versus specific CSR messages in advertisements in an environmental context. Journal of Marketing Communications 28: 253–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfer, Joseph. 2010. Lohas and the indigo dollar: Growing the spiritual economy. New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 4: 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gyarmati, Orsolya. 2021. A jövő újjáépítése—Top 10 fogyasztói trend 2021-ben. Trade Magazin. January 25. Available online: https://trademagazin.hu/hu/a-jovo-ujjaepitese-top-10-fogyasztoi-trend-2021-ben/ (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Howard, B. 2007. LOHAS consumers are taking the world by storm. Total Health 29: 58. [Google Scholar]

- IRI. 2021. Opportunities with Sustainability-Minded Fresh Consumers. Top Trends in Fresh. Available online: iriworldwide.com (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Johansen, Adrian. 2021. Gen Z Cares About Sustainability—Brands Should Too. Re/Make, May 10. Available online: https://remake.world/stories/humans-of-fashion/gen-z-cares-about-sustainability-brands-should-too/(accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Kamenidou, Irene C., Spyridon A. Mamalis, Stavros Pavlidis, and and Evangelia-Zoi G. Bara. 2019. Segmenting the Generation Z Cohort University Students Based on Sustainable Food Consumption Behavior: A Preliminary Study. Sustainability 11: 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korhonen, Virpi, and Kerttu-Maaria Ylipoti. 2018. Packaging Value by Generation—Results of a Finnish Study. Paper presented at the 21st IAPRI World Conference on Packaging, Zhuhai, China, 16 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Ildikó, Nándor Komáromi, and Georgina Rácz. 2013. Fenntartható fogyasztói értékrend mint az etikus vállalati magatartás kritériuma. Gazdálkodás: Scientific Journal on Agricultural Economics 57: 569–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreeb, Martin, Werner F. Schulz, Sandra Kirstein, Melanie Motzer, and Hans Hörschgen. 2009. Nachhaltigkeitsmarketing—Emotionalisierung durch Medialisierung. UWF Umwelt Wirtschafts Forum 17: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, Nicole Cecchele, Arthur Marcon, José Luis Duarte Ribeiro, Janine Fleith de Medeiros, Vandré Basbosa Brião, and Verner Luis Antoni. 2020. Determinant attributes and the compensatory judgement rules applied by young consumers to purchase environmentally sustainable food products. Sustainable Production and Consumption 23: 256–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, Rambabu, Charbel Jose Chiappetta Jabbour, Oksana Grebinevych, and David Roubaud. 2022. Green factors stimulating the purchase intention of innovative luxury organic beauty products: Implications for sustainable development. Journal of Environmental Management 301: 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehota, József, Éva Csíkné Mácsai, and Georgina Rácz. 2014. Az egészségtudatos élelmiszer-fogyasztói magatartás értelmezése a LOHAS koncepció alapján. Táplálkozásmarketing 1: 39–46. Available online: https://ojs.lib.unideb.hu/taplalkozasmarketing/article/view/9174/8293 (accessed on 20 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Marcketti, Sara B., and Mack C. Shelley. 2009. Consumer concern, knowledge and attitude towards counterfeit apparel products. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33: 327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matharu, Manita, Ruchi Jain, and Shampy Kamboj. 2020. Understanding the impact of lifestyle on sustainable consumption behavior: A sharing economy perspective. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 32: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, Juergen. 2011. From an Affluent Society to a Happy Society: Vital Signs Promising a Change and the Impacts on Industries. Hamburg: Diplomica Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Marketing Institute (NMI). 2008. The LOHAS Consumer Trends Report. Consumer Insights into the Role of Sustainability, Health, the Environment and Social Responsibility (Including A Focus on CSR, A Focus on Foods & Beverages, and A Focus on Personal Care). pp. 1–166. Available online: https://www.lohas.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Understanding-the-LOHAS-Consumer-11_LOHAS_Whole_Foods_Version.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Noh, Mijeong, Rodney Runyan, and Jon Mosier. 2014. Young consumers’ innovativeness and hedonic/utilitarian cool attitudes. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 42: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, Rainer. 2008. LOHAS und Best Ager—Hauptzielgruppe für Bio-Produkte aus der Region? Braunschweig: Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut. Available online: https://literatur.thuenen.de/digbib_extern/zi031821.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Origo. 2021. Meglepő Következtetésekre Jutott a Z Generációt Illetően egy Kutatás. Available online: https://www.origo.hu/gazdasag/20210713-generacio-kutatas-mastercard-jellemvonas-gazdasag.html (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Osti, Linda, and Gianluca Goffi. 2021. Lifestyle of health & sustainability: The hospitality sector’s response to a new market segment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 46: 360–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Hyun Hee. 2015. The Influence of LOHAS Consumption Tendency and Perceived Consumer Effectiveness on Trust and Purchase Intention Regarding Upcycling Fashion Goods. International Journal of Human Ecology 16: 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peyron, Carl. 2010. LOHAS—The Largest Market You’ve Never Heard of. London: Superbrands, Available online: https://www.lohas.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Superbrands2010LOHAS_CarlPeyron.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Pícha, Kamil, and Josef Navrátil. 2019. The factors of Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability influencing pro-environmental buying behaviour. Journal of Cleaner Production 234: 233–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittner, Martin. 2017. Consumer Segment LOHAS: Nachhaltigkeitsorientierte Dialoggruppen im Lebensmitteleinzelhandel. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). 2021. Die Gen Z legt Wert auf Nachhaltigkeit beim Einkauf—Und bei der Bundestagswahl. London: PwC, Available online: https://www.pwc.de/de/pressemitteilungen/2021/die-gen-z-legt-wert-auf-nachhaltigkeit-beim-einkauf-und-bei-der-bundestagswahl.html (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Reda, Ahmed, and Ravi Kapoor. 2021. The CEO Imperative: How Future Generations can Influence Companies to Focus on Sustainability. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_lb/future-consumer-index/the-ceo-imperative-how-future-generations-can-influence-companies-to-focus-on-sustainability (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Reicher, Regina Zsuzsánna, and Georgina Rácz. 2012. LOHAS témák megjelenése az offline és online magazinokban. He Appearance of the LOHAS Themes in the Offline and Online Magazines. Gazdaság & Társadalom/Journal of Economy & Society 2012: 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Jihyun, and Hongjoo Woo. 2019. Investigating male consumers’ lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS) and perception toward slow fashion. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49: 120–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakály, Zoltán, József Popp, Enikő Kontor, Sándor Kovács, Károly Pető, and Helga Jasák. 2017. Attitudes of the Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability Segment in Hungary. Sustainability 9: 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szakály, Zoltán, K. Pető, József Popp, and H. Jasák. 2015. A fenntartható fogyasztás iránt elkötelezett fogyasztói csoport, a LOHAS szegmens jellemzői. Táplálkozásmarketing 2: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakály, Zoltán. 2017. Élelmiszermarketing. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Fung Yi, Jane W. Y. Lung, Juliana da Silva, Mei Ha Lam, Pek I. Ng, and Ka Man Lok. 2021. A Study of Chinese Consumers towards Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability. Macao Polytechnic Institute. Economics and Business Quarterly Review 4: 144–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, Alec, Brian Kennedy, and Cary Funk. 2021. Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism, Social Media Engagement with Issue. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2021/05/PS_2021.05.26_climate-and-generations_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Veér, Bálint, Anett Janurik, and Vanda Sebestyén. 2018. Fogyasztói Mozgatóerők. Mi Irányítja a Sokoldalú Fogyasztót? Kereskedelem és Fogyasztói Piacok. Budapest: KPMG in Hungary, Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/hu/pdf/KPMG_Fogyasztoi_mozgatoerok.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Wightman-Stone, Danielle. 2022. Gen Z Consumers Want Better Gender Equality and Inclusion within Fashion. FashionUnited. March 2. Available online: https://fashionunited.uk/news/fashion/gen-z-consumers-want-better-gender-equality-and-inclusion-within-fashion/2022030261732 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Yan, Ruoh-Nan, Jennifer Paff Ogle, and Karen H. Hyllegard. 2010. The impact of message appeal and message source on Gen Y consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions toward American Apparel. Journal of Marketing Communications 16: 203–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, Eunah, Mary Lynn Damhorst, Stephen Sapp, and Russ Laczniak. 2003. Consumer adoption of the Internet: The case of apparel shopping. Psychology & Marketing 20: 1095–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Consciousness (Health and Environment Consciousness) | |

|---|---|

| Criteria Typical of the LOHAS Group | Research Results Concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Individualistic values | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS Group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Authentic values | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Ethical factors | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Philanthropic | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Corporate behaviour | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Hedonistic values | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Motivation of purchase | |

| Criteria of the LOHAS group | Research results concerning Generation Z |

|

|

| Scale Elements | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability and Environment Friendliness (α = 0.909), Total Mean = 3.86 | |||

| I am happy if I manage to buy a sustainable and/or healthy product. | 3.76 | 1.421 | 4.00 |

| I try to purchase as many sustainable products as possible. | 3.81 | 1.213 | 4.00 |

| I use more environmentally friendly solutions in everyday life. | 3.87 | 1.190 | 4.00 |

| I prefer environmentally friendly wrapping material when making purchases. | 3.93 | 1.383 | 4.00 |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for sustainable and environmentally conscious products. | 3.26 | 1.352 | 3.00 |

| I prefer the products of businesses which typically adopt a responsible and sustainable approach. | 3.66 | 1.281 | 4.00 |

| I am willing to share the knowledge I have gained in the subjects of sustainability and health. | 4.10 | 1.311 | 4.00 |

| Tradition and local values (α = 0.806), total mean = 3.39 | |||

| I prefer domestic products when making purchases. | 3.50 | 1.365 | 3.00 |

| I greatly prefer local (locally produced) products. | 3.93 | 1.383 | 3.00 |

| Traditions are important to me. | 3.76 | 1.480 | 4.00 |

| I consciously look for the trademarks of origin and quality on the products. | 2.95 | 1.531 | 3.00 |

| Hedonism (α = 0.821), total mean = 4.24 | |||

| I am open to the latest technologies. | 4.71 | 1.117 | 5.00 |

| I gladly and boldly try new things. | 4.51 | 1.203 | 5.00 |

| I gladly purchase sustainable and responsible products at present. | 4.36 | 1.353 | 4.00 |

| I gladly purchase and try sustainable products out of curiosity. | 3.99 | 1.338 | 4.00 |

| Knowledge and awareness (α = 0.789), total mean = 4.00 | |||

| Self-development is important to me and I regularly train myself. | 4.31 | 1.288 | 4.00 |

| I pay attention to conscious and healthy eating. | 3.84 | 1.392 | 4.00 |

| I exercise and work out regularly. | 4.05 | 1.562 | 4.00 |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for healthier products. | 3.85 | 1.307 | 4.00 |

| Naturalness is very important to me (e.g., products without additives). | 3.96 | 1.398 | 4.00 |

| Philanthropy (α = 0.707), total mean = 3.57 | |||

| I am willing to undertake voluntary work. | 3.11 | 1.488 | 3.00 |

| Supporting charity and donation programmes is important to me. | 3.33 | 1.439 | 3.00 |

| Purchasing products not tested on animals is important to me. | 4.26 | 1.603 | 4.00 |

| Individualism (α = 0.728), total mean = 3.27 | |||

| I prefer quality products when making purchases. | 3.29 | 1.426 | 3.00 |

| I tend to follow trends. | 3.19 | 1.511 | 3.00 |

| I prefer high quality products. | 3.34 | 1.188 | 4.00 |

| Authentic values (α = 0.568), total mean = 3.56 | |||

| I tend to be well-informed while shopping. | 3.82 | 1.406 | 4.00 |

| I purchase products from companies which are able to convince me of their values and which seem authentic to me. | 3.87 | 1.390 | 4.00 |

| I have received an environmentally conscious education from my family. | 3.89 | 1.247 | 4.00 |

| I tend to amplify negative news. | 2.67 | 1.329 | 3.00 |

| Factor | Scale Elements | Not Typical at All | Not Typical | Rather Not Typical | Rather Typical | Typical | Very Typical | TOP 3 Scale Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability and environment friendliness | I am happy if I manage to buy a sustainable and/or healthy product. | 6.44 | 14.01 | 22.41 | 23.53 | 21.29 | 12.32 | 57.14 |

| I try to purchase as many sustainable products as possible. | 2.52 | 12.04 | 25.49 | 30.25 | 21.57 | 8.12 | 59.94 | |

| I use more environmentally friendly solutions in everyday life. | 2.80 | 8.96 | 24.93 | 34.17 | 19.89 | 9.24 | 63.31 | |

| I prefer environmentally friendly wrapping material when making purchases. | 4.48 | 10.36 | 25.77 | 21.85 | 22.13 | 15.41 | 59.38 | |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for sustainable and environmentally conscious products. | 12.32 | 17.93 | 24.65 | 25.21 | 16.53 | 3.36 | 45.10 | |

| I prefer the products of businesses which typically adopt a responsible and sustainable approach. | 5.88 | 11.48 | 28.29 | 26.33 | 21.29 | 6.72 | 54.34 | |

| I am willing to share the knowledge I have gained in the subjects of sustainability and health. | 2.80 | 8.96 | 19.89 | 29.97 | 20.73 | 17.65 | 68.35 | |

| Tradition and local values | I prefer domestic products when making purchases. | 7.28 | 16.53 | 28.57 | 21.85 | 17.65 | 8.12 | 47.62 |

| I greatly prefer local (locally produced) products. | 10.92 | 17.93 | 26.89 | 24.93 | 12.04 | 7.28 | 44.26 | |

| Traditions are important to me. | 7.84 | 15.13 | 18.77 | 23.25 | 21.85 | 13.17 | 58.26 | |

| I consciously look for the trademarks of origin and quality on the products. | 21.01 | 24.09 | 19.33 | 17.65 | 10.64 | 7.28 | 35.57 | |

| Hedonism | I am open to the latest technologies. | 0.28 | 2.80 | 13.17 | 22.13 | 33.05 | 28.57 | 83.75 |

| I gladly and boldly try new things. | 1.68 | 3.64 | 14.85 | 25.77 | 30.25 | 23.81 | 79.83 | |

| I gladly purchase sustainable and responsible products at present. | 3.64 | 5.60 | 16.25 | 25.21 | 24.37 | 24.93 | 74.51 | |

| I gladly purchase and try sustainable products out of curiosity. | 3.36 | 11.76 | 20.17 | 26.61 | 23.81 | 14.29 | 64.71 | |

| Knowledge and awareness | Self-development is important to me and I regularly train myself. | 1.96 | 5.32 | 20.45 | 27.73 | 20.73 | 23.81 | 72.27 |

| I pay attention to conscious and healthy eating. | 5.32 | 12.61 | 21.85 | 27.45 | 18.49 | 14.29 | 60.22 | |

| I exercise and work out regularly. | 5.88 | 14.01 | 17.65 | 18.49 | 19.61 | 24.37 | 62.46 | |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for healthier products. | 5.32 | 11.48 | 18.49 | 31.93 | 23.53 | 9.24 | 64.71 | |

| Naturalness is very important to me (e.g., products without additives). | 3.36 | 12.89 | 23.25 | 23.53 | 19.33 | 17.65 | 60.50 | |

| Philanthropy | I am willing to undertake voluntary work. | 16.25 | 21.57 | 24.65 | 18.49 | 10.92 | 8.12 | 37.54 |

| Supporting charity and donation programmes is important to me. | 10.92 | 18.77 | 28.01 | 20.17 | 12.89 | 9.24 | 42.30 | |

| Purchasing products not tested on animals is important to me. | 7.84 | 7.84 | 15.41 | 20.45 | 15.97 | 32.49 | 68.91 | |

| Individualism | I prefer to purchase brands. | 14.57 | 15.69 | 21.01 | 29.41 | 13.17 | 6.16 | 48.74 |

| I tend to follow trends. | 17.37 | 18.77 | 21.01 | 19.33 | 17.65 | 5.88 | 42.86 | |

| I prefer high quality products. | 2.80 | 5.60 | 17.93 | 31.93 | 29.69 | 12.04 | 73.67 | |

| Authentic values | I tend to be well-informed while shopping. | 5.04 | 14.85 | 21.29 | 24.65 | 20.73 | 13.45 | 58.82 |

| I purchase products from companies which are able to convince me of their values and which seem authentic to me. | 8.40 | 6.72 | 20.17 | 31.65 | 20.17 | 12.89 | 64.71 | |

| I have received an environmentally conscious education from my family. | 4.48 | 7.56 | 23.53 | 33.33 | 20.73 | 10.36 | 64.43 | |

| I tend to amplify negative news. | 22.69 | 25.77 | 25.49 | 17.37 | 5.04 | 3.64 | 26.05 |

| Factor | Cluster | Fitting the LOHAS Model | Cluster That Nearly Fits the LOHAS | Far from LOHAS | ANOVA p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | ||

| Sustainability and environment friendliness | I am happy if I manage to buy a sustainable and/or healthy product. | 4.95 | 0.952 | 5.00 | 3.81 | 1.230 | 4.00 | 2.56 | 1.022 | 3.00 | 0.000 |

| I try to purchase as many sustainable products as possible. | 4.98 | 0.795 | 5.00 | 3.88 | 0.808 | 4.00 | 2.58 | 0.809 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I use more environmentally friendly solutions in everyday life. | 4.97 | 0.826 | 5.00 | 3.84 | 0.864 | 4.00 | 2.87 | 0.976 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I prefer environmentally friendly wrapping material when making purchases. | 5.10 | 0.898 | 5.00 | 4.01 | 1.114 | 4.00 | 2.69 | 1.062 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for sustainable and environmentally conscious products. | 4.48 | 0.941 | 5.00 | 3.38 | 0.998 | 3.00 | 1.90 | 0.819 | 2.00 | 0.000 | |

| I prefer the products of businesses which typically adopt a responsible and sustainable approach. | 4.84 | 0.804 | 5.00 | 3.73 | 0.964 | 4.00 | 2.42 | 0.889 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I am willing to share the knowledge I have gained in the subjects of sustainability and health. | 5.12 | 0.860 | 5.00 | 4.21 | 0.990 | 4.00 | 2.95 | 1.194 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| Tradition and local values | I prefer domestic products when making purchases. | 4.59 | 1.088 | 5.00 | 3.55 | 1.172 | 4.00 | 2.40 | 0.961 | 3.00 | 0.000 |

| I greatly prefer local (locally produced) products. | 4.46 | 1.240 | 5.00 | 3.24 | 1.073 | 3.00 | 2.32 | 1.073 | 2.00 | 0.000 | |

| Traditions are important to me. | 4.58 | 1.246 | 5.00 | 3.85 | 1.262 | 4.00 | 2.84 | 1.489 | 2.50 | 0.000 | |

| I consciously look for the trademarks of origin and quality on the products. | 4.33 | 1.294 | 4.00 | 2.80 | 1.280 | 3.00 | 1.85 | 0.983 | 2.00 | 0.000 | |

| Hedonism | I am open to the latest technologies. | 5.29 | 0.860 | 6.00 | 4.72 | 0.987 | 5.00 | 4.13 | 1.220 | 4.00 | 0.000 |

| I gladly and boldly try new things. | 5.25 | 0.896 | 5.00 | 4.39 | 1.145 | 4.50 | 3.97 | 1.202 | 4.00 | 0.000 | |

| I gladly purchase sustainable and responsible products at present. | 5.49 | 0.720 | 6.00 | 4.56 | 0.855 | 4.50 | 2.98 | 1.238 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I gladly purchase and try sustainable products out of curiosity. | 5.05 | 0.908 | 5.00 | 4.06 | 1.122 | 4.00 | 2.87 | 1.080 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| Knowledge and awareness | Self-development is important to me and I regularly train myself. | 5.24 | 0.916 | 6.00 | 4.23 | 1.095 | 4.00 | 3.55 | 1.314 | 3.00 | 0.000 |

| I pay attention to conscious and healthy eating. | 4.96 | 1.106 | 5.00 | 3.81 | 1.125 | 4.00 | 2.82 | 1.180 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I exercise and work out regularly. | 4.80 | 1.220 | 5.00 | 3.88 | 1.552 | 4.00 | 3.60 | 1.628 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I am willing to pay a higher price for healthier products. | 4.81 | 0.877 | 5.00 | 3.95 | 1.093 | 4.00 | 2.77 | 1.151 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| Naturalness is very important to me (e.g., products without additives). | 5.30 | 0.775 | 5.00 | 3.99 | 1.003 | 4.00 | 2.63 | 1.072 | 2.50 | 0.000 | |

| Philanthropy | I am willing to undertake voluntary work. | 4.21 | 1.280 | 4.00 | 3.03 | 1.323 | 3.00 | 2.17 | 1.194 | 2.00 | 0.000 |

| Supporting charity and donation programmes is important to me. | 4.45 | 1.127 | 4.00 | 3.33 | 1.205 | 3.00 | 2.26 | 1.191 | 2.00 | 0.000 | |

| Purchasing products not tested on animals is important to me. | 5.17 | 1.031 | 6.00 | 4.39 | 1.359 | 4.00 | 3.21 | 1.788 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| Individualism | I prefer to purchase brands. | 3.33 | 1.429 | 4.00 | 3.34 | 1.340 | 4.00 | 3.18 | 1.550 | 3.00 | 0.639 |

| I tend to follow trends. | 3.25 | 1.528 | 3.00 | 3.15 | 1.463 | 3.00 | 3.18 | 1.575 | 3.00 | 0.869 | |

| I prefer high quality products. | 4.49 | 1.155 | 5.00 | 4.17 | 1.089 | 4.00 | 3.84 | 1.278 | 4.00 | 0.000 | |

| Authentic values | I tend to be well-informed while shopping. | 4.62 | 1.291 | 5.00 | 3.75 | 1.197 | 4.00 | 3.15 | 1.433 | 3.00 | 0.000 |

| I purchase products from companies, which are able to convince me of their values and which seem authentic to me. | 4.80 | 1.020 | 5.00 | 3.95 | 1.187 | 4.00 | 2.88 | 1.327 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I have received an environmentally conscious education from my family. | 4.63 | 1.046 | 5.00 | 3.88 | 1.128 | 4.00 | 3.22 | 1.214 | 3.00 | 0.000 | |

| I tend to amplify negative news. | 2.97 | 1.374 | 3.00 | 2.70 | 1.299 | 3.00 | 2.35 | 1.268 | 2.00 | 0.003 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lendvai, M.B.; Kovács, I.; Balázs, B.F.; Beke, J. Health and Environment Conscious Consumer Attitudes: Generation Z Segment Personas According to the LOHAS Model. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070269

Lendvai MB, Kovács I, Balázs BF, Beke J. Health and Environment Conscious Consumer Attitudes: Generation Z Segment Personas According to the LOHAS Model. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(7):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070269

Chicago/Turabian StyleLendvai, Marietta Balázsné, Ildikó Kovács, Bence Ferenc Balázs, and Judit Beke. 2022. "Health and Environment Conscious Consumer Attitudes: Generation Z Segment Personas According to the LOHAS Model" Social Sciences 11, no. 7: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070269

APA StyleLendvai, M. B., Kovács, I., Balázs, B. F., & Beke, J. (2022). Health and Environment Conscious Consumer Attitudes: Generation Z Segment Personas According to the LOHAS Model. Social Sciences, 11(7), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070269