The Family Transmission of Ethnic Prejudice: A Systematic Review of Research Articles with Adolescents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

No child is born with prejudice (…)The context of his/her learning is alwaysthe structure where his/her personality develops.

1.1. Prejudice and Ethnicity

1.2. Intergenerational Transmission of Ethnic Prejudice

1.3. The Present Study

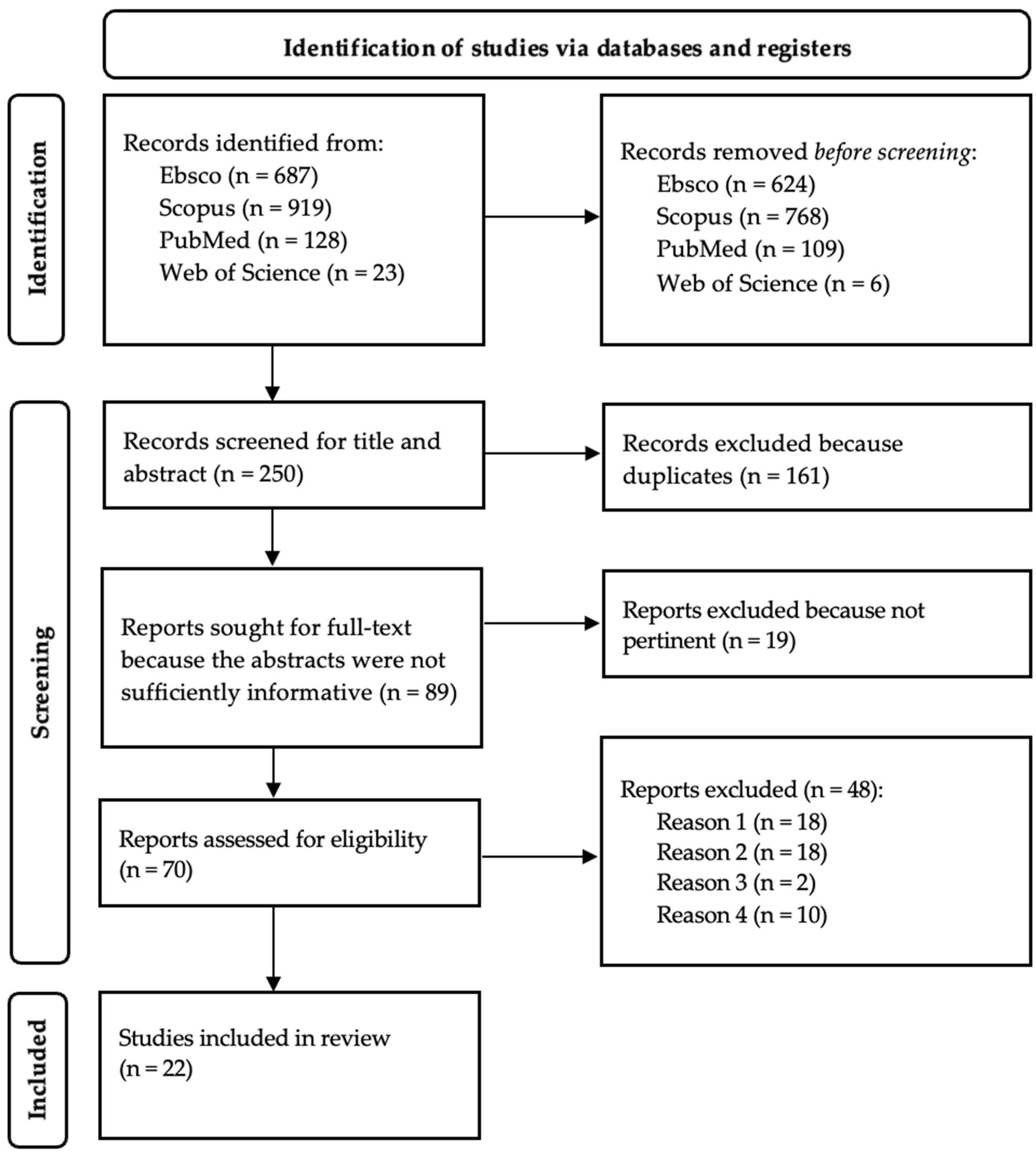

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Data Source and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3.2. Main Characteristics of the Included Studies

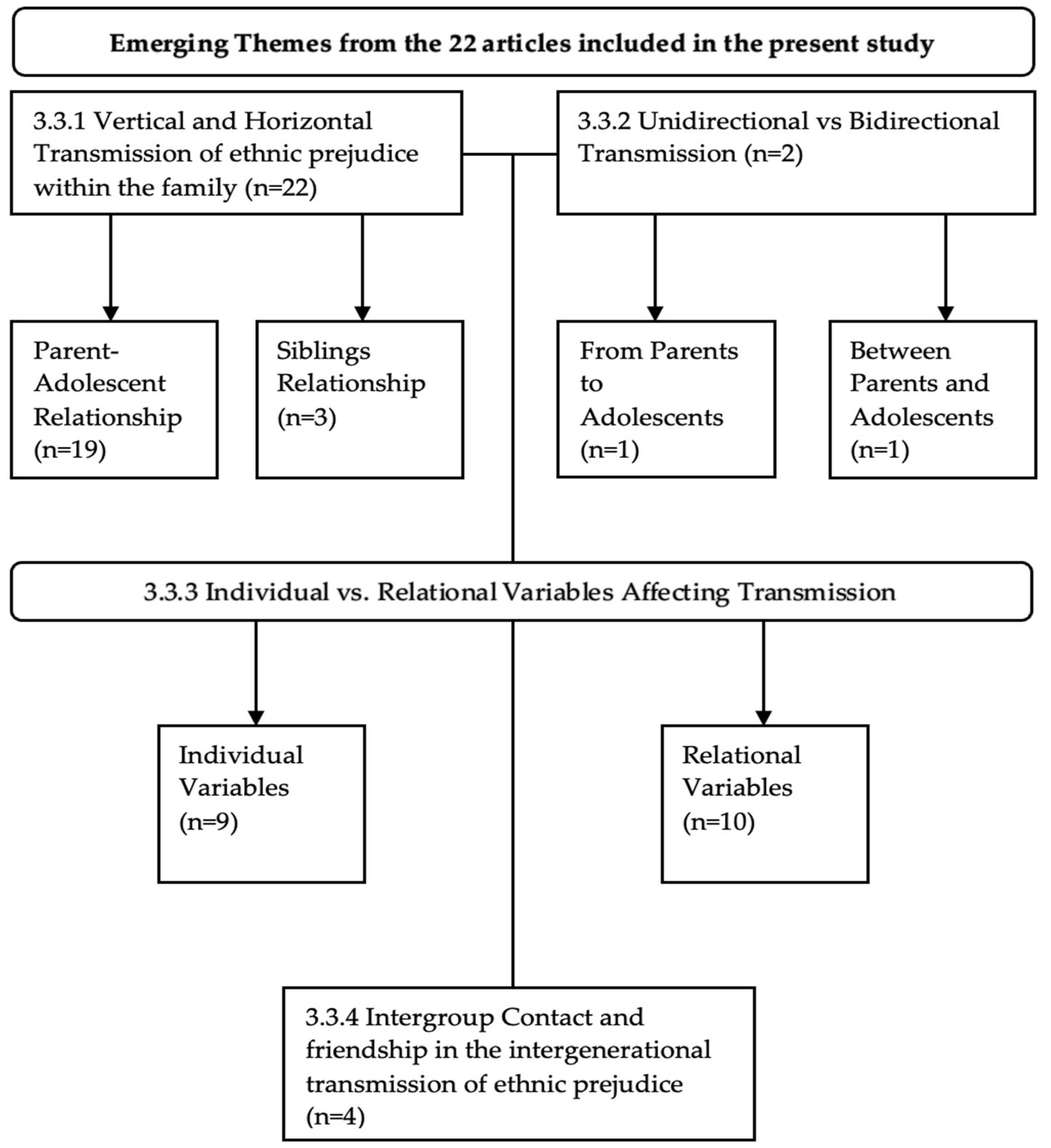

3.3. Emerging Themes

3.3.1. Vertical and Horizontal Transmission

3.3.2. Unidirectional and Bidirectional Transmission

3.3.3. Individual and Relational Variables Affecting Transmission

3.3.4. Intergroup Contact

3.4. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Practical Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Explicit attitudes are deliberate and controlled responses, while implicit attitudes are automatic and spontaneous responses (Castelli et al. 2009). |

| 2 | Although we carried out the literature search through the keywords combination in English, Italian, and Romanian, only the studies written in English met the eligibility criteria. |

References

- Aboud, Frances E. 2005. The Development of Prejudice in Childhood and Adolescence. In On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years after Allport. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 310–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, Frances E. 2008. A Social-Cognitive Developmental Theory of Prejudice. In Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud, Frances E., and Anna-Beth Doyle. 1996. Parental and Peer Influences on Children’s Racial Attitudes. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 20: 371–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, Isabelle, and Dieter Ferring. 2012. Intergenerational Value Transmission within the Family and the Role of Emotional Relationship Quality. Family Science 3: 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alfieri, Sara, and Elena Marta. 2015. Sibling Relation, Ethnic Prejudice, Direct and Indirect Contact: There Is a Connection? Europe’s Journal of Psychology 11: 664–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. The Nature of Prejudice. Oxford: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 1995. Broad and Narrow Socialization: The Family in the Context of a Cultural Theory. Journal of Marriage and Family 57: 617–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagci, Sabahat Cigdem, and Olesya Blazhenkova. 2020. Unjudge Someone: Human Library as a Tool to Reduce Prejudice toward Stigmatized Group Members. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 42: 413–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, Stephen, and Michael D. Kahn. 1975. Sisterhood-Brotherhood Is Powerful: Sibling Sub-Systems and Family Therapy. Family Process 14: 311–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela. 2009. Trasmettere Valori: Tre Generazioni Familiari a Confronto [Transmitting Values: Three Family Generations in Comparison], 1st ed. SocialMente 23. Milano: Ed. UNICOPLI. [Google Scholar]

- Barni, Daniela, Sonia Ranieri, Eugenia Scabini, and Rosa Rosnati. 2011. Value Transmission in the Family: Do Adolescents Accept the Values Their Parents Want to Transmit? Journal of Moral Education 40: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Sara Alfieri, Elena Marta, and Rosa Rosnati. 2013. Overall and Unique Similarities between Parents’ Values and Adolescent or Emerging Adult Children’s Values. Journal of Adolescence 36: 1135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Ariel Knafo, Asher Ben-Arieh, and Muhammad M. Haj-Yahia. 2014. Parent–Child Value Similarity Across and Within Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45: 853–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Silvia Donato, Rosa Rosnati, and Francesca Danioni. 2017. Motivations and Contents of Parent-Child Value Transmission. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 45: 180–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John W., John Widdup Berry, Ype H. Poortinga, Marshall H. Segall, and Pierre R. Dasen. 2002. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Billig, Michael. 1989. The Argumentative Nature of Holding Strong Views: A Case Study. European Journal of Social Psychology 19: 203–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Kate. 2013. The Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty. In Chronic Poverty. Edited by Andrew Shepherd and Julia Brunt. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechwald, Whitney A., and Mitchell J. Prinstein. 2011. Beyond Homophily: A Decade of Advances in Understanding Peer Influence Processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence 21: 166–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, Rupert. 1995. Prejudice: It’s Social Psychology, 2nd ed. Gloucester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Rupert, and Samuel L Gaertner. 2001. Intergroup Processes. Malden: Blackwell Publishers, Available online: http://site.ebrary.com/id/10233057 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Carlson, James M., and Joseph Iovini. 1985. The Transmission of Racial Attitudes from Fathers to Sons: A Study of Blacks and Whites. Adolescence 20: 233–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castelli, Luigi, Cristina Zogmaister, and Silvia Tomelleri. 2009. The Transmission of Racial Attitudes within the Family. Developmental Psychology 45: 586–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Set Correlation and Contingency Tables. Applied Psychological Measurement 12: 425–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, Richard J., Sofia Stathi, Rhiannon N. Turner, and Senel Husnu. 2009. Imagined Intergroup Contact: Theory, Paradigm and Practice. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 3: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, Elisabetta, Flavia Albarello, Francesca Prati, and Monica Rubini. 2021. Development of Prejudice against Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities in Adolescence: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Developmental Review 60: 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, Alfred. 1983. Learning to Be Prejudiced Growing Up in Multi-Ethnic Britain. London: London Edward Arnold, Available online: http://library.lincoln.ac.uk/items/17797 (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- De Mol, Jan, Gilbert Lemmens, Lesley Verhofstadt, and Leon Kuczynski. 2013. Intergenerational Transmission in a Bidirectional Context. Psychologica Belgica 53: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denham, Susanne A., Kimberly A. Blair, Elizabeth DeMulder, Jennifer Levitas, Katherine Sawyer, Sharon Auerbach-Major, and Patrick Queenan. 2003. Preschool Emotional Competence: Pathway to Social Competence? Child Development 74: 238–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhont, Kristof, and Alain Van Hiel. 2012. Intergroup Contact Buffers against the Intergenerational Transmission of Authoritarianism and Racial Prejudice. Journal of Research in Personality 46: 231–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhont, Kristof, Arne Roets, and Alain Van Hiel. 2013. The Intergenerational Transmission of Need for Closure Underlies the Transmission of Authoritarianism and Anti-Immigrant Prejudice. Personality and Individual Differences 54: 779–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dovidio, John F. 2001. On the Nature of Contemporary Prejudice: The Third Wave. Journal of Social Issues 57: 829–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, Martin J., Marnie L. Brennan, Hywel C. Williams, and Rachel S. Dean. 2016. Development of a Critical Appraisal Tool to Assess the Quality of Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 6: e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duriez, Bart. 2004. RESEARCH: A Research Note on the Relation Between Religiosity and Racism: The Importance of the Way in Which Religious Contents Are Being Processed. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 14: 177–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, Bart. 2011. Adolescent Ethnic Prejudice: Understanding the Effects of Parental Extrinsic Versus Intrinsic Goal Promotion. The Journal of Social Psychology 151: 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, Bart, and Bart Soenens. 2009. The Intergenerational Transmission of Racism: The Role of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation. Journal of Research in Personality 43: 906–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, Bart, Bart Soenens, and Maarten Vansteenkiste. 2008. The Intergenerational Transmission of Authoritarianism: The Mediating Role of Parental Goal Promotion. Journal of Research in Personality 42: 622–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, Katharina, Jan Šerek, and Peter Noack. 2018. And What About Siblings? A Longitudinal Analysis of Sibling Effects on Youth’s Intergroup Attitudes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 47: 383–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Ralph, and Samuel Shozo Komorita. 1966. Childhood Prejudice as a Function of Parental Ethnocentrism, Punitiveness, and Outgroup Characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3: 259–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gniewosz, Burkhard, and Peter Noack. 2015. Parental Influences on Adolescents’ Negative Attitudes Toward Immigrants. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44: 1787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotevant, Harold D., and Catherine R. Cooper. 1985. Patterns of Interaction in Family Relationships and the Development of Identity Exploration in Adolescence. Child Development 56: 415–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grusec, Joan E., and Jacqueline J. Goodnow. 1994. Impact of Parental Discipline Methods on the Child’s Internalization of Values: A Reconceptualization of Current Points of View. Developmental Psychology 30: 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hello, Evelyn, Peer Scheepers, Ad Vermulst, and Jan R. M. Gerris. 2004. Association between Educational Attainment and Ethnic Distance in Young Adults: Socialization by Schools or Parents? Acta Sociologica 47: 253–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, Mikael, Maureen A. Eger, and Rickard Danell. 2018. Peer Attitudes and the Development of Prejudice in Adolescence. Socius 4: 2378023118763187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, Diane, James Rodriguez, Emilie P. Smith, Deborah J. Johnson, Howard C. Stevenson, and Paul Spicer. 2006. Parents’ Ethnic-Racial Socialization Practices: A Review of Research and Directions for Future Study. Developmental Psychology 42: 747–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijnk, Willem, and Aart C. Liefbroer. 2012. Family Influences on Intermarriage Attitudes: A Sibling Analysis in the Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and Family 74: 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jablonski, Nina G. 2021. Skin Color and Race. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 175: 437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaat, Jan G., and Avril Keating. 2019. Are Today’s Youth More Tolerant? Trends in Tolerance among Young People in Britain. Ethnicities 19: 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaspers, Eva, Marcel Lubbers, and Jannes de Vries. 2008. Parents, Children and the Distance between Them: Long Term Socialization Effects in the Netherlands. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 39: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jugert, Philipp, Katharina Eckstein, Andreas Beelmann, and Peter Noack. 2016. Parents’ Influence on the Development of Their Children’s Ethnic Intergroup Attitudes: A Longitudinal Analysis from Middle Childhood to Early Adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 13: 213–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Phyllis A. 2003. Racists or Tolerant Multiculturalists? How Do They Begin?’ American Psychologist 58: 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killen, Melanie, and Charles Stangor. 2001. Children’s Social Reasoning about Inclusion and Exclusion in Gender and Race Peer Group Contexts. Child Development 72: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knafo, Ariel, and Avi Assor. 2007. Motivation for Agreement with Parental Values: Desirable When Autonomous, Problematic When Controlled. Motivation and Emotion 31: 232–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, Ariel, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2003. Parenting and Adolescents’ Accuracy in Perceiving Parental Values. Child Development 74: 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafo, Ariel, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2004. Identity Formation and Parent-Child Value Congruence in Adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 22: 439–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordyaka, Bastian, Katharina Jahn, Bjoern Niehaves, Samuli Laato, and University of Turku, Faculty of Education, Turku, Finland. 2020. Implicit Learning in Video Games—Intergroup Contact and Multicultural Competencies. In WI2020 Zentrale Tracks. Edited by Norbert Gronau, Moreen Heine, Hanna Krasnova and K. Pousttchi. Berlin-Charlottenburg: GITO Verlag, pp. 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynski, Leon, and Geoffrey S. Navara. 2006. Sources of Innovation and Change in Socialization, Internalization and Acculturation. In Handbook of Moral Development. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 299–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski, Leon, and C. Melanie Parkin. 2007. Agency and Bidirectionality in Socialization: Interactions, Transactions, and Relational Dialectics. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 259–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski, Leon, Sheila Marshall, and Kathleen Schell. 1997. Value Socialization in a Bidirectional Context. In Parenting and Children’s Internalization of Values: A Handbook of Contemporary Theory. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kulik, Liat. 2004. The Impact of Birth Order on Intergenerational Transmission of Attitudes from Parents to Adolescent Sons: The Israeli Case. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33: 149–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannoy, Séverine, Theodora Duka, Carina Carbia, Joël Billieux, Sullivan Fontesse, Valérie Dormal, Fabien Gierski, Eduardo López-Caneda, Edith V. Sullivan, and Pierre Maurage. 2021. Emotional Processes in Binge Drinking: A Systematic Review and Perspective. Clinical Psychology Review 84: 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E. E. 2003. Dynamic Viewpoints on Parent-Child Relations—Their Implications for Socialisation Processes. In Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations. Edited by Leon Kuczynski. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 439–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, Jay A., and Gary L. Bowen. 2013. Families and Communities: A Social Organization Theory of Action and Change. In Handbook of Marriage and the Family, 3rd ed. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, pp. 781–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel Rose. 2008. Pride, Prejudice, and Ambivalence: Toward a Unified Theory of Race and Ethnicity. American Psychologist 63: 651–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markus, Hazel Rose, and Paula M. L. Moya, eds. 2010. Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, Susan M., Shawn D. Whiteman, Ji-Yeon Kim, and Ann C. Crouter. 2007. Characteristics and Correlates of Sibling Relationships in Two-Parent African American Families. Journal of Family Psychology 21: 227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, Cecil. 2014. The Parent–Child Similarity in Cross-Group Friendship and Anti-Immigrant Prejudice: A Study among 15-Year Old Adolescents and Both Their Parents in Belgium. Journal of Research in Personality 50: 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, Cecil, and Kristof Dhont. 2015. Parent–Child Similarity in Common and Specific Components of Prejudice: The Role of Ideological Attitudes and Political Discussion. European Journal of Personality 29: 585–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miklikowska, Marta. 2016. Like Parent, like Child? Development of Prejudice and Tolerance towards Immigrants. British Journal of Psychology 107: 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miklikowska, Marta. 2017. Development of Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Adolescence: The Role of Parents, Peers, Intergroup Friendships, and Empathy. British Journal of Psychology 108: 626–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miklikowska, Marta, Andrea Bohman, and Peter F. Titzmann. 2019. Driven by Context? The Interrelated Effects of Parents, Peers, Classrooms on Development of Prejudice among Swedish Majority Adolescents. Developmental Psychology 55: 2451–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, Lily, and Joel R. Anderson. 2019. A Systematic Literature Review of the Relationship between Dark Personality Traits and Antisocial Online Behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences 144: 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, Donald L., and Alvin Scodel. 1960. Relationships between Ethnocentrism in Children and the Ethnocentrism and Authoritarian Rearing Practices of Their Mothers. Child Development 31: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musetti, Alessandro, Tommaso Manari, Joël Billieux, Vladan Starcevic, and Adriano Schimmenti. 2022. Problematic Social Networking Sites Use and Attachment: A Systematic Review. Computers in Human Behavior 131: 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishna, Michael, Adrian V. Bell, Joseph Henrich, Cameron M. Curtin, Alexander Gedranovich, Jason McInerney, and Braden Thue. 2020. Beyond Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) Psychology: Measuring and Mapping Scales of Cultural and Psychological Distance. Psychological Science 31: 678–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryan, Megan, Harold D. Fishbein, and P. Neal Ritchey. 2004. Intergenerational Transmission of Prejudice, Sex Role Stereotyping, and Intolerance. Adolescence 39: 407–26. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 1994. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pagani, Camilla, and Francesco Robustelli. 2010. Young People, Multiculturalism, and Educational Interventions for the Development of Empathy. International Social Science Journal 61: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauker, Kristin, Evan P. Apfelbaum, Carol S. Dweck, and Jennifer L. Eberhardt. 2022. Believing That Prejudice Can Change Increases Children’s Interest in Interracial Interactions. Developmental Science, e13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Bill E., and Lauren E. Duncan. 1999. Authoritarianism of Parents and Offspring: Intergenerational Politics and Adjustment to College. Journal of Research in Personality 33: 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., and R. W. Meertens. 1995. Subtle and Blatant Prejudice in Western Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology 25: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, Tobias, and Andreas Beelmann. 2011. Development of Ethnic, Racial, and National Prejudice in Childhood and Adolescence: A Multinational Meta-Analysis of Age Differences. Child Development 82: 1715–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, S., and D. Barni. 2012. Family and Other Social Contexts in the Intergenerational Transmission of Values. Family Science 3: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekker, Roderik. 2016. The Lasting Impact of Adolescence on Left-Right Identification: Cohort Replacement and Intracohort Change in Associations with Issue Attitudes. Electoral Studies 44: 120–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Clyde C., Barbara Mandleco, S. Frost Olsen, and Craig H. Hart. 2001. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ). Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques 3: 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, José-Miguel, and Ulrich Wagner. 2009. Learning to Be Prejudiced: A Test of Unidirectional and Bidirectional Models of Parent–Offspring Socialization. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33: 516–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roest, Annette M. C., Judith Semon Dubas, and Jan R. M. Gerris. 2010. Value Transmissions between Parents and Children: Gender and Developmental Phase as Transmission Belts. Journal of Adolescence 33: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, Claudia, Francesca Danioni, and Daniela Barni. 2019. La relazione tra il disimpegno morale e comportamenti trasgressivi in adolescenza: Il ruolo moderatore dell’alessitimia. [The relation between moral disengagement and transgressive behaviors in adolescence: The moderating role of alexithymia]. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo 2: 247–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, Claudia, Anna Dell’Era, Ioana Zagrean, Francesca Danioni, and Daniela Barni. 2022. Activating Self-Transcendence Values to Promote Prosocial Behaviors among Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Moderating Role of Positive Orientation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 183: 263–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, Adam, Dominic Abrams, and Sheri Levy. 2007. Introduction: Extending the Conversation: Transdisciplinary Approaches to Social Identity and Intergroup Attitudes in Children and Adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development 31: 417–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sameroff, Arnold, ed. 2009. The Transactional Model of Development: How Children and Contexts Shape Each Other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scabini, Eugenia. 1999. Psicologia Sociale della Famiglia: Sviluppo dei Legami e Trasformazioni Sociali [Family Social Psychology: Relationship Development and Social Transformations]. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Scabini, Eugenia, and Vittorio Cigoli. 2000. Il Famigliare: Legami, Simboli e Transizioni [The Family: Bonds, Symbols and Transitions, 1st ed. Collana di psicologia clinica e psicoterapia 130. Milano: Cortina. [Google Scholar]

- Scabini, Eugenia, and Raffaella Iafrate. 2019. Psicologia dei Legami Familiari. [The Psychology of Family Bonds]. Nuova Editione. Itinerari. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Schönpflug, Ute. 2001. Intergenerational Transmission of Values: The Role of Transmission Belts. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 32: 174–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönpflug, Ute, and Ludwig Bilz. 2009. The Transmission Process: Mechanisms and Contexts. In Cultural Transmission: Psychological, Developmental, Social, and Methodological Aspects. Culture and Psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 212–39. [Google Scholar]

- Senguttuvan, Umadevi, Shawn D. Whiteman, and Alexander C. Jensen. 2014. Family Relationships and Adolescents’ Health Attitudes and Weight: The Understudied Role of Sibling Relationships. Family Relations 63: 384–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, Giovanna, Gabrielle Coppola, and Rosalinda Cassibba. 2015. The Transmission of Attachment across Generations: The State of Art and New Theoretical Perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 56: 315–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, Chris G., and John Duckitt. 2008. Personality and Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review 12: 248–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, Judith G., Marc Jambon, and Courtney Ball. 2014. The Social Domain Approach to Children’s Moral and Social Judgments. In Handbook of Moral Development, 2nd ed. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Thijs, Paula, Manfred Te Grotenhuis, and Peer Scheepers. 2018. The Paradox of Rising Ethnic Prejudice in Times of Educational Expansion and Secularization in the Netherlands, 1985–2011. Social Indicators Research 139: 653–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Rhiannon N., and Rupert Brown. 2008. Improving Children’s Attitudes Toward Refugees: An Evaluation of a School-Based Multicultural Curriculum and an Anti-Racist Intervention1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38: 1295–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, Rhiannon N., Richard J. Crisp, and Emily Lambert. 2007. Imagining Intergroup Contact Can Improve Intergroup Attitudes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 10: 427–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, Adriana J., and Nancy E. Hill. 2020. Ethnic–Racial Socialization in the Family: A Decade’s Advance on Precursors and Outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family 82: 244–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Váradi, Luca, Ildikó Barna, and Renáta Németh. 2021. Whose Norms, Whose Prejudice? The Dynamics of Perceived Group Norms and Prejudice in New Secondary School Classes. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 524547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voci, Alberto, and Lisa Pagotto. 2010. Il Pregiudizio: Che Cosa è, Come Si Riduce [Prejudice: What It Is, How to Reduce it], 1st ed. Scienze Della Mente 48. Roma: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Walpole, Sarah Catherine. 2019. Including Papers in Languages Other than English in Systematic Reviews: Important, Feasible, yet Often Omitted. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 111: 127–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Fiona A., and Melanie Gleitzman. 2006. An Examination of Family Socialisation Processes as Moderators of Racial Prejudice Transmission Between Adolescents and Their Parents. Journal of Family Studies 12: 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, Shawn D., Susan M. McHale, and Ann C. Crouter. 2007. Competing Processes of Sibling Influence: Observational Learning and Sibling Deidentification. Social Development 16: 642–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, Bernard E., and Gregory D. Webster. 2019. The Relationships of Intergroup Ideologies to Ethnic Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review 23: 207–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, Cathy Spatz, and Helen W. Wilson. 2015. Intergenerational Transmission of Violence. In Violence and Mental Health. Edited by Jutta Lindert and Itzhak Levav. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölfer, Ralf, Katharina Schmid, Miles Hewstone, and Maarten Van Zalk. 2016. Developmental Dynamics of Intergroup Contact and Intergroup Attitudes: Long-Term Effects in Adolescence and Early Adulthood. Child Development 87: 1466–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors, Year of Publication | Country | Focus of the Study | Research Design and Instruments | Participants | Vertical or Horizontal Transmission | Testing Bidirectionality Transmission Yes/No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfieri and Marta (2015) | Italy | Sibling relationship’s role in the socialization of ethnic prejudice | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 88 sibling dyads | Horizontal | No |

| Carlson and Iovini (1985) | USA | Relationship between racial attitudes of fathers and sons | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 200 dyads (father–son) | Vertical | No |

| Dhont and Van Hiel (2012) | Belgium | Role of intergroup contact in the intergenerational transmission of racial prejudice | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 99 dyads (one parent and one adolescent) | Vertical | No |

| Dhont et al. (2013) | Belgium | Similarity between parents’ and children’s anti-immigrant prejudice | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 169 dyads (one parent and one adolescent) | Vertical | No |

| Duriez (2011) | Belgium | Role of parental figure in adolescent ethnic prejudice | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 240 mother–child dyads and 210 father–child dyads | Vertical | No |

| Duriez and Soenens (2009) | Belgium | Intergenerational transmission of racism | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 528 mother–child dyads and 447 father–child dyads | Vertical | No |

| Duriez et al. (2008) | Belgium | Intergenerational transmission of authoritarian submission and authoritarian dominance as predictor of prejudice | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire | 536 mother-child dyads and 472 father–child dyads | Vertical | No |

| Eckstein et al. (2018) | Germany | Siblings’ influence on intergroup attitudes | Longitudinal (2 waves); Self-report questionnaires | 117 sibling dyads | Horizontal | No |

| Rodríguez-García and Wagner (2009) | Costa Rica | Models of transmission between parent–adolescent attitudes towards immigrants | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 408 dyads (one parent and one adolescent) | Vertical | No |

| Gniewosz and Noack (2015) | Germany | Parent–adolescent transmission of attitudes towards immigrants | Longitudinal (5 waves) and 3 cohorts; Self-report questionnaires | 339 mother–son dyads; 433 mother–daughter dyads; 292 father–son dyads; 362 father–daughter dyads | Vertical | No |

| Hello et al. (2004) | The Netherlands | Effects of educational attainment compared to parental influence on ethnic prejudice of mid/late adolescents | Longitudinal (2 waves); Self-report questionnaires | T1: 484 triads with mother, father, and one adolescent; T2: 301 triads with mother, father, and one adolescent | Vertical | No |

| Jaspers et al. (2008) | The Netherlands | Parent–child similarities with respect to attitudes towards ethnic minorities | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 367 triads with mother, father, and adolescent | Vertical | No |

| Jugert et al. (2016) | Germany | Influence of parents’ ethnic intergroup attitudes on the development of their children’s ethnic intergroup attitudes | Longitudinal (5 waves); Self-report questionnaires | 184 mothers, 158 fathers, and 188 adolescents | Vertical | No |

| Kulik (2004) | Israel | Birth order and its impact on intergenerational transmission of parental attitudes towards immigrants | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 294 families with mother, father, and two siblings | Vertical | No |

| McHale et al. (2007) | USA | Sibling relationships and family characteristic regarding racial socialization | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires and interviews | 172 families with mother, father, and two siblings | Horizontal | No |

| Meeusen (2014) | Belgium | Parental role in the anti-immigrant prejudice of their children | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 1708 triads with mother, father, and adolescent | Vertical | No |

| Meeusen and Dhont (2015) | Belgium | Parent–child similarity in different types of prejudice, including ethnic prejudice | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 1530 triads with mother, father, and adolescent | Vertical | No |

| Miklikowska (2016) | Sweden | Influence of parents’ prejudice and tolerance towards immigrants on adolescents’ attitudes and vice versa (from adolescents to parents) | Longitudinal (2 waves); Self-report questionnaires | 507 triads with mother, father, and adolescent | Vertical | Yes |

| Miklikowska (2017) | Sweden | The effects of parents on adolescents’ anti-immigrant attitudes | Longitudinal (3 waves); Self-report questionnaires | 517 triads with mother, father, and adolescent | Vertical | No |

| Miklikowska et al. (2019) | Sweden | The effects of parents’ attitudes on changes in youth anti-immigrant attitudes | Longitudinal (3 waves); Self-report questionnaires | T1: 438 triads (mother, father, adolescent), T2: 330 triads (mother, father, adolescent), T3: 246 triads (mother, father, adolescent) | Vertical | No |

| O’Bryan et al. (2004) | USA | The intergenerational transmission of prejudice and stereotyping | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | 111 triads with mother, father, and adolescent | Vertical | No |

| White and Gleitzman (2006) | Australia | The association of parents’ racial attitudes with adolescents’ racial attitudes | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaires | Family triads with 86 mothers, 75 fathers, and 93 adolescents | Vertical | No |

| Authors (Year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 * | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | Q17 | Q18 | Q19 * | Q20 | Total Quality Score/20 | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfieri and Marta (2015) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | NR | 14 | Moderate |

| Carlson and Iovini (1985) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 14 | Moderate |

| Dhont and Van Hiel (2012) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 15 | High |

| Dhont et al. (2013) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 17 | High |

| Duriez (2011) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | NR | 17 | High |

| Duriez and Soenens (2009) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | NR | 15 | Moderate |

| Duriez et al. (2008) | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 13 | Moderate |

| Eckstein et al. (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | NR | 18 | High |

| Rodríguez-García and Wagner (2009) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 19 | High |

| Gniewosz and Noack (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 18 | High |

| Hello et al. (2004) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 19 | High |

| Jaspers et al. (2008) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | NR | 18 | High |

| Jugert et al. (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 19 | High |

| Kulik (2004) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 17 | High |

| McHale et al. (2007) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 15 | Moderate |

| Meeusen (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 19 | High |

| Meeusen and Dhont (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 19 | High |

| Miklikowska (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 18 | High |

| Miklikowska (2017) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 18 | High |

| Miklikowska et al. (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 18 | High |

| O’Bryan et al. (2004) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 16 | Moderate |

| White and Gleitzman (2006) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | 14 | Moderate |

| Mean | 16.82 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard deviation | 3.87 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zagrean, I.; Barni, D.; Russo, C.; Danioni, F. The Family Transmission of Ethnic Prejudice: A Systematic Review of Research Articles with Adolescents. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060236

Zagrean I, Barni D, Russo C, Danioni F. The Family Transmission of Ethnic Prejudice: A Systematic Review of Research Articles with Adolescents. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(6):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060236

Chicago/Turabian StyleZagrean, Ioana, Daniela Barni, Claudia Russo, and Francesca Danioni. 2022. "The Family Transmission of Ethnic Prejudice: A Systematic Review of Research Articles with Adolescents" Social Sciences 11, no. 6: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060236

APA StyleZagrean, I., Barni, D., Russo, C., & Danioni, F. (2022). The Family Transmission of Ethnic Prejudice: A Systematic Review of Research Articles with Adolescents. Social Sciences, 11(6), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11060236