The Livelihood of Chinese Migrants in Timor-Leste

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objective and Methodology

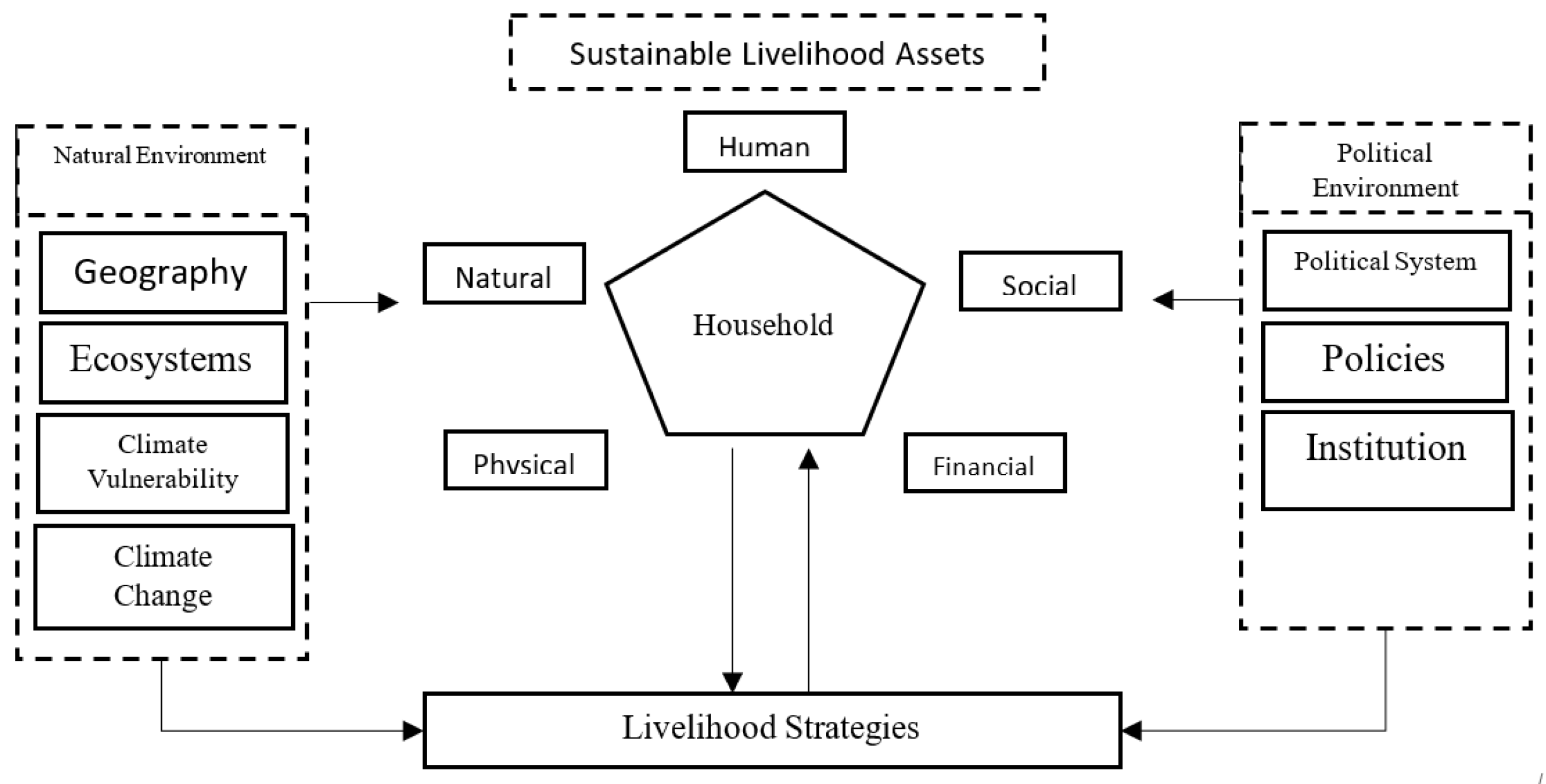

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Migration Experience and Adaptation of Migrant Workers from China in Timor-Leste

3.2. Entrepreneurial Experience in Timor-Leste

3.3. Strategy to Maintain Business during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdurrahim, Ali Yansyah, Arya Hadi Dharmawan, Satyawan Sunito, and I. Made Sudiana. 2014. Kerentanan Ekologi dan Strategi Penghidupan Pertanian Masyarakat Desa Persawahan Tadah Hujan di Pantura Indramayu. Journal Kependudukan Indonesia 9: 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Bakar, Noor Rahamah, and Mohd Yusof Abdullah. 2008. The Life History Approach: Fieldwork Experience. E-Bangi 3: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, Ikpe Justice, Elijah Abasifreke Paul Udoh, and Bamidele Adebisi. 2020. Small business awareness and adoption of state-of-the-art technologies in emerging and developing markets, and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 34: 123–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldairany, Shaza, Rosmini Omar, and Farzana Quoquab. 2018. Systematic review: Entrepreneurship in conflict and post conflict. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 10: 361–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancok, Djamaludin. 2003. Modal Sosial Dan Kualitas Masyarakat. Psikologika: Jurnal Pemikiran Dan Penelitian Psikologi 15: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ashley, Caroline, and Diana Carney. 1999. Sustainable Livelihoods: Lessons from Early Experience; London: Department for International Development.

- Blignault, Ilse, Vince Ponzio, Rong Ye, and Maurice Eisenbruch. 2008. A qualitative study of barriers to mental health services utilisation among migrants from mainland China in South-East Sydney. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 54: 180–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, Manuel. 2017. Responsabilidade Social Corporativa: O Caso Das Empresas Em Timor-Leste. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn, Miranda. 2008. Indigenous entrepreneurship, culture and micro-enterprise in the Pacific Islands: Case studies from Samoa. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 20: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelo, Ana, Conceição Santos, and Maria Arminda Pedrosa. 2014. Education for sustainable development in East Timor. Asian Education and Development Studies 3: 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Robert, and Gordon R. Conway. 1992. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century. IDS Discussion Paper 296. Brighton: IDS. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Terence Tai Leung, Xiaoyang Li, and Cornelia Yip. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on ASEAN. Economic and Political Studies 9: 166–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Rongwei, Matthew Liu, and Guicheng James Shi. 2015. How rural-urban identification influences consumption patterns? Evidence from Chinese migrant workers. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 27: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, Eugenia, and Alicia Girón. 2020. The Limits of the “Progressive” Institutional Change: Migration and Remittances Experiences. Journal of Economic Issues 54: 454–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaika, Mathias. 2015. Migration and Economic Prospects. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41: 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, Leo. 2017. Livelihoods in development. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 38: 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DFID. 2008. DFID’s Sustainable Livelihoods Approach and Its Framework. Available online: http://www.glopp.ch/B7/en/multimedia/B7_1_pdf2.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Duan, Jinyun, Juelin Yin, Yue Xu, and Daoyou Wu. 2020. Should I stay or should I go? Job demands’ push and entrepreneurial resources’ pull in Chinese migrant workers’ return-home entrepreneurial intention. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 32: 429–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikhof, Doris Ruth. 2020. COVID-19, inclusion and workforce diversity in the cultural economy: What now, what next? Cultural Trends 29: 234–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Frank. 1998. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. Journal of Development Studies 35: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, Carla, Manuel Brito, and Iris Barbosa. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility: The Case of East Timor Multinationals. Corporate Social Responsibility in Management and Engineering 99: 99–146. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Xiaolan, Jing Zhang, and Liming Wang. 2020. Introduction to the special section: The impact of Covid-19 and post-pandemic recovery: China and the world economy. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 18: 311–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Wenshu, and Russel Smyth. 2011. What keeps China’s migrant workers going? expectations and happiness among China’s floating population. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 16: 163–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, John, and Susan Olivia. 2020. Direct and Indirect Effects of Covid-19 On Life Expectancy and Poverty in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 56: 325–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. 2021. Timor-Leste in 2020 Counting the Costs of Coronavirus. Asian Survey 61: 155–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Zhonghua, and Tuo Liang. 2017. Differentiating citizenship in urban China: A case study of Dongguan city. Citizenship Studies 21: 773–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, Harapan, Abram L. Wagner, Amanda Yufika, Wira Winardi, Samsul Anwar, Alex Kurniawan Gan, Abdul M. Setiawan, Yogambigai Rajamoorthy, Hizir Sofyan, Trung Quang Vo, and et al. 2020. Willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 16: 3074–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, Joseph H., William Hatcher, and V. Brooks Poole. 2018. Social entrepreneurship in Trujillo, Peru: The case of Nisolo. Community Development 49: 312–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Ludovic. 2006. Security sector reform in East Timor, 1999–2004. International Peacekeeping 13: 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, Wade, and Peter Hayes. 2000. East Timor and Asian security. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 32: 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, Sue, Lia Kent, and Andrew McWilliam. 2015. A New Era?: Timor-Leste after the UN. In A New Era?: Timor-Leste after the UN. Canberra: ANU Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizuka, Katsumi. 2004. Australia’s policy towards East Timor. Round Table 8533: 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Iyanatul. 2000. East Timor: Development Outlook. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 5: 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, Avril. 2021. COVID-19 and the African cultural economy: An opportunity to reimagine and reinvigorate? Cultural Trends 30: 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkawa, Gen. 2007. Japan and east timor: Change and development of Japan’s security policy and the road to east timor. Japanese Studies 27: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, Jeffrey. 2006. Balancing justice and reconciliation in East Timor. Critical Asian Studies 38: 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, Ayu. 2015. Modal Sosial dan Mekanisme Adaptasi Masyarakat Pedesaan dalam Pengelolaan dan Pembangunan Infrastruktur. MASYARAKAT Jurnal Sosiologi 20: 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaver, Richard. 2001. Introduction: Australia, East Timor and Indonesia. Pacific Review 14: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Maggy, Anita Chan, Hannah Bradby, and Gill Green. 2002. Chinese migrant women and families in Britain. Women’s Studies International Forum 25: 607–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Maggi W. H. 2003. Beyond Chinese, beyond food: Unpacking the regulated Chinese restaurant business in Germany. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 15: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, John, and Paul Milbourne. 2014. Migrant workers and migrant entrepreneurs: Changing established/outsider relations across society and space? Space and Polity 18: 255–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, Eric W., and Thomas G. Pittz. 2020. Strategies for small business: Surviving and thriving in the era of COVID-19. Journal of the International Council for Small Business 1: 106–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Kerry. 2021. COVID-19 and the Chinese economy: Impacts, policy responses and implications. International Review of Applied Economics 35: 308–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ding, Weihong Sun, and Xuan Zhang. 2020. Is the Chinese Economy Well Positioned to Fight the COVID-19 Pandemic? The Financial Cycle Perspective. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 56: 2259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, Andrew. 2007. Development, foreign aid and post-development in Timor-Leste. Third World Quarterly 28: 155–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noer, Khaerul Umam. 2018. Mereka yang Keluar dari Rumahnya: Pengalaman Perempuan Madura di Bekasi. Jurnal Inada: Kajian Perempuan Indonesia Di Daerah Tertinggal, Terdepan, Dan Terluar 1: 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Sue, Andresw McWilliam, Jack N. Fenner, and Sally Brockwell. 2012. Examining the Origin of Fortifications in East Timor: Social and Environmental Factors. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 7: 200–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivia, Susana, Jhon Gibson, and Rus’an Nasrudin. 2020. Indonesia in the Time of Covid-19. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 56: 143–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Aihwa. 2003. Cyberpublics and Diaspora Politics Among Transnational Chinese. Interventions 5: 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossome, Lyn. 2020. The care economy and the state in Africa’s Covid-19 responses. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 42: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Hua. 2010. Rural-to-Urban Labor Migration, Household Livelihoods, and the Rural Environment in Chongqing Municipality, Southwest China. Human Ecology 38: 675–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, Vanessa. 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 32: 503–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Geoffrey. 2001. People’s war: Militias in East Timor and Indonesia. South East Asia Research 9: 271–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, Choyon Kumar. 2017. Dynamics of climatic and anthropogenic stressors in risking island-char livelihoods: A case of northwestern Bangladesh. Asian Geographer 34: 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, Giacomo. 2020. The mixed embeddedness of transnational migrant entrepreneurs: Moroccans in Amsterdam and Milan. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46: 2067–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strating, Rebecca. 2013. East Timor’s Emerging National Security Agenda: Establishing “Real” Independence. Asian Security 9: 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahra, Rusydi. 2003. Modal sosial: Konsep dan aplikasi. Jurnal Masyarakat Dan Budaya 5: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanter, Richard. 2000. East Timor and the crisis of the Indonesian intelligence state. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 32: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Qing, Liying Guo, and Lin Zheng. 2016. Urbanization and rural livelihoods: A case study from Jiangxi Province, China. Journal of Rural Studies 47: 577–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timisela, Marthen, Daniel D. Kameo, Neil Samuel Rupidara, and Roberth Siahainenia. 2020. Traditional farmers of Wamena tribes in Jayapura-Indonesia. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika 26: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Leste. 2017. Minitry of finance Press release-Tibar Bay Port PPP Project. In Díli; December 15. Available online: https://www.mof.gov.tl/press-release-tibar-bay-port-ppp-project/?lang=en (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- Tridakusumah, Ahmad Choibar, Mira Elfina, Dyah Ita Mardiyaningsih, Jepri Pioke, and Sahrain Bumulo. 2015. Pola Adaptasi Ekologi Dan Strategi Nafkah Rumahtangga Di Desa Pangumbahan. Sodality Jurnal Sosiologi Pedesaan 3: 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubadji, Annie, Karima Kourtit, and Peter Nijkamp. 2014. Social capital and local cultural milieu for successful migrant entrepreneurship: Impact assessment of bonding vs. bridging and cultural gravity in The Netherlands. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 27: 301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, David. 2004. Japan and East Timor: Implications for the Australia-Japan relationship. Japanese Studies 24: 233–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jinpu, and Ning Zhan. 2019. Nationalism, overseas Chinese state and the construction of ‘Chineseness’ among Chinese migrant entrepreneurs in Ghana. Asian Ethnicity 20: 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaobing, Renfu Luo, Linxiu Zhang, and Scott Rozelle. 2017. The Education Gap of China’s Migrant Children and Rural Counterparts. Journal of Development Studies 53: 1865–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Xuan, and Hongge Zhu. 2020. Return migrants’ entrepreneurial decisions in rural China. Asian Population Studies 16: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, Rathna, M. Baiquni, and Rika Harini. 2016. Strategi Penghidupan Berkelanjutan Masyarakat Berbasis Aset di Sub DAS Pusur, DAS Bengawan Solo. Jurnal Wilayah Dan Lingkungan 4: 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk-ha Tsang, Eileen. 2020. Being Bad to Feel Good: China’s Migrant Men, Displaced Masculinity, and the Commercial Sex Industry. Journal of Contemporary China 29: 221–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniarto, Paulus Rudolf. 2016. Dari Pekerja ke Wirausaha: Migrasi Internasional, Dinamika Tenaga Kerja, dan Pembentukan Bisnis Migran Indonesia di Taiwan. Jurnal Kajian Wilayah 3: 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, Tanya, and Yordanos Seifu Estifanos. 2016. Somewhere else: Social connection and dislocation of Ethiopian migrants in Johannesburg. African and Black Diaspora 9: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Barrero, Richard, and Zenia Hellgren. 2020. Harnessing the potential of Moroccans living abroad through diaspora policies? Assessing the factors of success and failure of a new structure of opportunities for transnational entrepreneurs. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46: 2027–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Shaohua. 2019. Accumulation by and without dispossession: Rural land use, land expropriation, and livelihood implications in China. Journal of Agrarian Change 19: 447–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zongwe, Dunia. P. 2015. Seven Myths about Chinese Migrants in Africa. Transnational Corporations Review 7: 480–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewee’s Initials | Driving Factor | Pulling Factor | Adaptation Process in Host Country | Home Country Policy and Institutional Support | Business Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCH | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by family (following brother) | Borrowing capital and entrepreneurship; building relationships by employing local people; getting support from fellow migrants (relatives); | There is institutional support (banks) in China to provide business loans | Store building |

| ELN | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended family (following uncle) | Collecting capital with entrepreneurship before migration; employing local people. | There is institutional support (banks) in China, but it has not been utilized. | Store building |

| CHY | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by family (following father) | Learning Indonesian and Tetun through association with employees (local communities); resolving conflict through a good social network. | There is institutional support (banks) in China, but it has not been utilized. | Entertainment business |

| LNC | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by friend | Building positive relations with local communities for business security; business-related violations are resolved amicably. | There is institutional support (banks) in China, but it has not been utilized. | Grocery business |

| JCH | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by friend | Collecting capital with entrepreneurship; building positive relationships with local communities | There are support institutions (banks) in China to provide loans | Construction company |

| LC | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by family | Collecting capital by working as an employee in a family-owned business | There is institutional support (banks) in China but not yet utilized | Grocery business |

| TT | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by family (following brother) | Obtaining business capital from the family; building positive relationships with local communities | There is institutional support (banks) in China but not yet utilized | Food and home appliances business |

| ST | Home country business competition | Business opportunities in Timor-Leste and recommended by friend | Collecting capital with entrepreneurship before migration; building positive relationships with local communities | There is institutional support (banks) in China but not yet utilized | ATK material provider business |

| Interviewee’s Initials | Mobility and Access to Capital to Sustaining Livelihoods in Timor-Leste | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Capital | Financial Capital | Human Capital | Physical Capital | Natural Capital | Information | |

| CCH | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | The same business intensification in different locations. |

| ELN | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Different business diversification in different locations. |

| CHY | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Transforming the basic food business into an entertainment and lodging business. |

| LNC | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Grocery store business expansion |

| JHC | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Business transformation from a construction material supplier to a construction company |

| LC | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Business expansion in different locations. |

| TT | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Product diversification and business extensification in different locations. |

| ST | Expansion results | Initial capital | Initial capital | Expansion results | Expansion results | Different business diversification in different locations. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernandes, A.; Prabawa, T.S.; Therik, W.M.A. The Livelihood of Chinese Migrants in Timor-Leste. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040157

Fernandes A, Prabawa TS, Therik WMA. The Livelihood of Chinese Migrants in Timor-Leste. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(4):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040157

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandes, Ajito, Titi Susilowati Prabawa, and Wilson M. A. Therik. 2022. "The Livelihood of Chinese Migrants in Timor-Leste" Social Sciences 11, no. 4: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040157

APA StyleFernandes, A., Prabawa, T. S., & Therik, W. M. A. (2022). The Livelihood of Chinese Migrants in Timor-Leste. Social Sciences, 11(4), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040157