1. Introduction

Currently, the scientific community generates an unprecedented amount of information that can potentially be used to meet the current challenges of humanity. Furthermore, the advancement of information technologies, especially the internet, sets an appropriate context for researchers to collaborate, communicate and exchange information to advance scientific knowledge and meet the needs of society (

García-Peñalvo 2010;

Hampton et al. 2015). This resonates with the progress of science observed during the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when the free circulation of knowledge was among one of the core pillars (

Bisol et al. 2014;

Merton 1984). However, in recent times, economic interests tend to prevent the free flow of knowledge, favoring its capitalization as the basic feature of the current system of science (

Krishna 2014;

Macfarlane and Cheng 2008).

De Ridder (

2013) points out that researchers in some institutions are invited to patent their inventions to generate economic benefits to increase their budgets. Likewise, publishers charge exorbitant fees for those who need to access to scientific publications (

Brown 2016), even if those publications were financed with public funds. This situation evidences the need to develop mechanisms that allow equitable access to science.

In this line of thought, Open Science presents itself as a framework that promises unrestricted access to the various elements of the scientific endeavor. As such, Open Science is a model of knowledge production that depends on the openness of the processes, inputs, and results of research to make them accessible to anyone within and outside the scientific community to the extent in which digitization makes it possible (

Bisol et al. 2014;

García-Peñalvo 2010;

Mukherjee and Stern 2009). This attempts to make the research process more efficient, transparent, and inclusive for scientists and society (

Grand et al. 2012;

Peters 2010). In addition, its implementation requires the participation of various actors, including researchers, governments, funders, foundations, universities, research centers, publishers, libraries, companies, and society in general (

OECD 2015). Although Open Science is usually related to open access to publications (Open Access), it also includes free access to educational resources (Open Educational Resources), notes (Open Notebooks), methods (Open Methods), codes (Open Source), peer review (Open Peer Review), as well as research data (Open Data) (

Hampton et al. 2015;

McKiernan et al. 2016). In this research, the focus is on the latter.

Research data are a fundamental input in any process of scientific inquiry. In this paper, we understand research data as quantitative or qualitative records of facts employed as evidence to answer research questions, and that are commonly accepted by the scientific community as essential to validate the findings of scientific research (

HEFCE et al. 2016;

OECD 2007). Among others, research data can be transcripts of interviews, photographs, videos, measurements, observations, statistical records, or the results of surveys and experiments (

ERC 2017). One characteristic of research data is that they generally remain hidden from public scrutiny; however, open research data, as a strand of Open Science, suggests that research data should be made available to the public. This quality of openness lies in the possibility that anyone can access, exploit, transform and distribute the data freely, provided that there is an acknowledgment to the person who generated them in case it is requested (

HEFCE et al. 2016). Additionally, information technologies now enable the sharing of data in repositories, internet sites and email (

Kim and Zhang 2015). In short, the variety and amount of data that can be shared, as well as the existing channels to do so, offer an enormous potential for exploitation.

According to the scientific literature, sharing research data provides different benefits. First, it stimulates scientific and technological progress since it is possible to build new knowledge based on existing data (

Zuiderwijk and Spiers 2019). In this regard,

Pitt and Tang (

2013) point out that this benefit represents a maximization of the utility and lifetime of research data. Second, sharing research data favors the verification of results since access to inputs is provided to replicate the experiments and the techniques used to arrive to particular findings (

Whyte and Pryor 2011). This is especially relevant in contexts in which the credibility of the scientific institution has been undermined, either by fraudulent practices or by the reproducibility crisis that certain disciplines face (

Grubb and Easterbrook 2011;

Wicherts 2011). Third, the distribution of data promotes collaboration between scientists and institutions as it promotes co-authorship, and invitations to participate in events or projects (

Nguyen et al. 2017); this is necessary, particularly when the challenges we face today require the intervention of different approaches. Fourth, the sharing of research data increases the visibility of researchers and institutions and the recognition they receive from their peers (

McKiernan et al. 2016). Similarly,

Costello (

2009) states that the above offers positive effects on the reputation and opportunities of those who share research data freely.

However, the scientific literature also provides evidence on various factors that inhibit the openness of research data. For researchers, the risk of violating confidentiality issues when they share their data prevents them from doing so (

Wiley and Mischo 2016). According to

Fecher et al. (

2015), the time and effort required by researchers to curate their research data to facilitate their subsequent use discourage them to share. In addition, the fact that data can be misused if misinterpreted, either by taking the data out of context or by using them for commercial purposes, inhibits their distribution (

Costello 2009;

Cragin et al. 2010;

Nguyen et al. 2017). Furthermore,

Choudhury et al. (

2014) found that there is resistance from the side of researchers to share their data when these data are subjected to public scrutiny. In other cases, sharing data becomes a threat that translates into lost opportunities of scientists to publish (

Zuiderwijk and Spiers 2019). In addition, the willingness to share data is associated with the age and position of the researcher, especially among the youngest who tend to protect the data they possess (

Andreoli-Versbach and Mueller-Langer 2014). For

Kuipers and Van Der Hoeven (

2009), the affiliation of scientists influences data sharing, since they prefer to share with those who collaborate closely. In addition, researchers often choose not to share their data once they have had negative previous experiences (

Nguyen et al. 2017). Finally, the absence of infrastructure (

Wiley and Mischo 2016), support services (

Link et al. 2017), and training (

Wallis et al. 2013) to curate and share data prevent researchers from getting involved in sharing.

Previous research has also found that belonging to a particular scientific discipline also influences the willingness of researchers to share data with others. Existing evidence shows that there is a greater disposition to share within pure sciences (

Cragin et al. 2010;

Zuiderwijk and Spiers 2019), whereas, on the contrary, this trend is lower in areas of medical and social sciences (

Jarolimkova and Drobikova 2018;

Jeng et al. 2016). In the social sciences, for instance, the fact that the data are frequently linked to the identity of the subjects studied, and thus their privacy may be at risk (

Curty et al. 2016), undermine the researchers´ disposition to share. Additionally, given that social sciences tend to use qualitative data to which there are no clearly established standards that favor their curation, preparation and openness (

Mannheimer et al. 2019) hinder data sharing. This is not a minor concern since this limitation can restrict the potential use of research data. This situation particularly affects areas of research that provide solutions to problems related to disadvantaged sectors (

Neuman 2013), where social and cultural aspects of society are studied (

May 2011), or research that attempts to improve the quality of life of certain communities (

Alasuutari et al. 2008). It would be convenient that social scientists share their research data, as in doing so can increase our understanding of phenomena that affect social life, especially when the research conducted is financed with public resources.

Now, in the case of Mexico, little is known about the social researchers´ interests to share research data. Although Mexico is the third country in the Latin American region to legislate on Open Science, most of what has been accomplished falls within the area of open access to publications (

Babini and Rovelli 2020). A new Law on Science and Technology (

Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión 2014) boosted the creation of 82 institutional open access repositories with the support of the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) (

CONACYT 2016,

2017b,

2018) during 2015, 2016 and 2017. These were intended to promote free access to scientific publications, products of technological development and research data (

CONACYT 2017a). However, the opening of the latter has been slow since there are no incentives that persuade researchers to share their research data. Consequently, sharing research data is subject to individual initiatives taken by researchers. As such, the objective of this article is to analyze the interests and motivations of social researchers to share research data within the context of a Mexican university.

2. Materials and Methods

This research follows the Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT) approach. According to

Charmaz (

2014), this “consists of systematic, yet flexible guidelines for collecting and analyzing qualitative data to construct theories from the data themselves” (p. 2). Unlike the classical version, the CGT refutes the idealized objectivity of Glaser’s proposal and emphasizes that theories are built by social scientists based on their interactions with the environment, the participants and their experiences, as well as with their prior knowledge (

Charmaz 2014). In this regard, early literature review in this research played a fundamental role, informing this study (

Ramalho et al. 2015). As such, it allowed us to become familiar with previous studies on the phenomenon under investigation and to identify existing knowledge gaps. Complementary,

Dunne (

2011) points out that the literature stimulates the development of theoretical sensitivity to enable an adequate orientation of the research process, and to avoid conceptual and methodological pitfalls. On this point, the review of previous work contributed to the development of the instrument to collect data and to conduct its subsequent analysis. Testimonies of research participants were prioritized over the literature when creating the conceptual categories. Finally, this study resonates with

Charmaz (

2014) in that the literature review allows us to show the contribution of this paper to existing knowledge.

Regarding the stages of CGT, various authors (

Charmaz et al. 2017;

Chun Tie et al. 2019;

O’Connor et al. 2018) agree that, despite the epistemological and ontological differences of the method, these remain essentially constant.

Marradi et al. (

2007) describes its four stages. First, the data initially collected is contrasted to gather fragments that show similar passages to develop initial categories. Second, based on a constant comparative analysis of the data, categories and their properties are developed and integrated to establish an initial theory. This phase is complemented by conducting a subsequent data collection. Third, a delimitation of the theory is performed from the conceptual categories that build it; if the analysis of new data does not modify or reveal new categories, the processes of data collection and analysis come to an end. Finally, the results of the new theory are written.

To collect data, twelve semi-structured interviews were conducted. The interviews followed a script with open and flexible questions that were adapted according to the needs of each encounter (see

Appendix A). In this sense, it was sought that the participants openly shared their opinions and experiences regarding the openness of data in science. The testimonies of 12 researchers from the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) of Mexico were the basis of the study, lasting between 30–45 min. All testimonies were recorded and digitally transcribed, with prior authorization from the interviewees. To select research participants, six women and six men belonging to the National System of Researchers (SNI) of Mexico were chosen, expecting their membership to the SNI could guarantee their active participation in scientific research, as well as their familiarization with research data. An initial purposeful sampling (

Morse 2007) was followed to interview 4 research participants who demonstrated active involvement in conducting scientific research. As the initial codes and categories were constructed, data collection was complemented with a theoretical sampling (

Charmaz 2008;

Morse 2007) in order to empirically test the initial codes and categories. Data collection ended once the analysis of new data did not yield new information in relation to the categories; that is, when theoretical saturation was achieved.

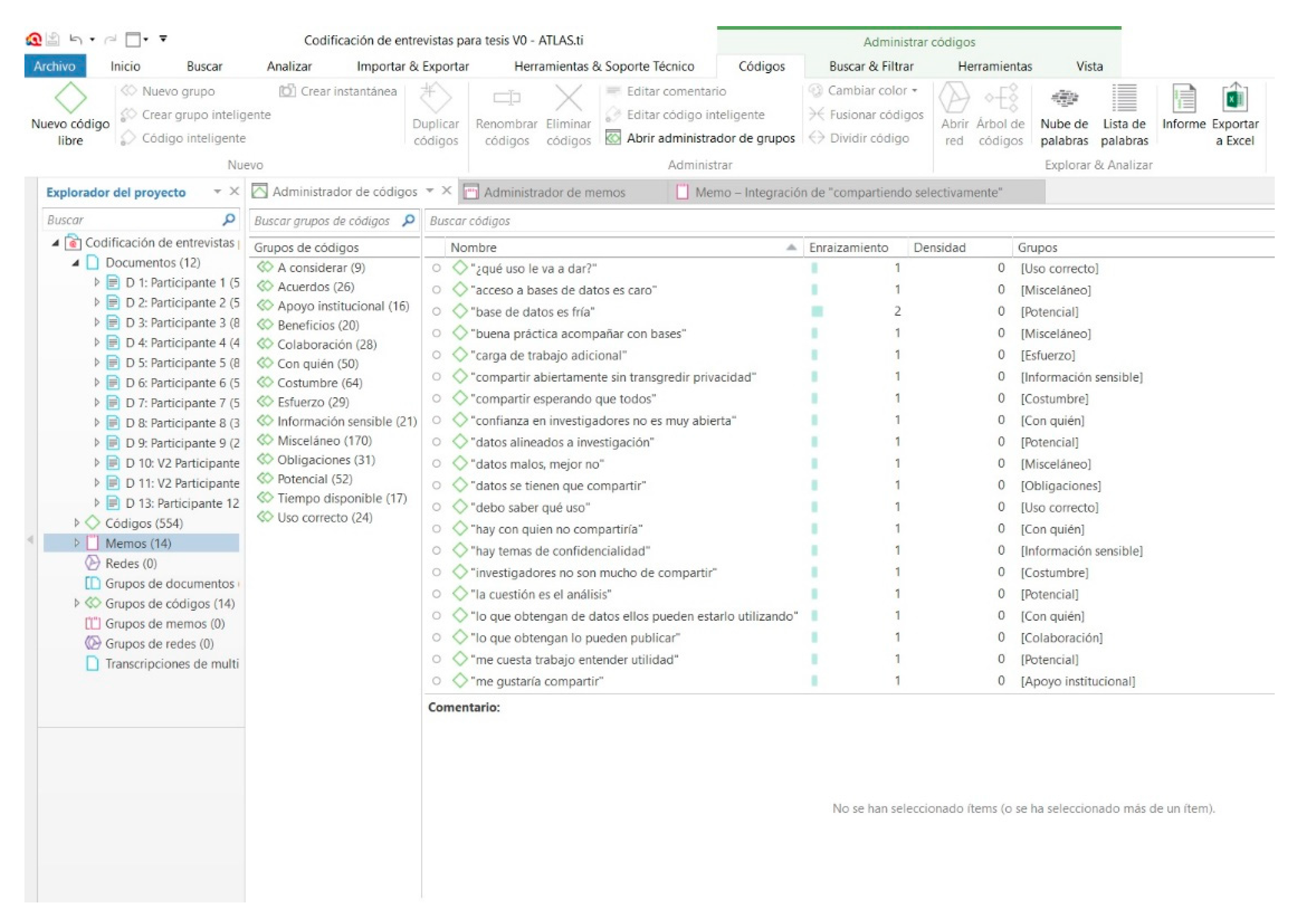

To conduct the data analysis, the software ATLAS.ti 8 was used, following the principles of the CGT method. An initial coding of data generated during the purposeful sampling was carried out. Coding profiles by process and in vivo (

Saldaña 2013) were used to fragment the data, ensuring the fidelity of the interviewees’ testimonies. The constant comparison of the data and the initial codes allowed us to identify patterns within the data and to generate tentative conceptual categories that were later validated and adjusted through new data collected following a theoretical sampling. Afterward, a second data coding cycle based on a selective profile (

Charmaz 2014;

Saldaña 2013) started in order to accomplish the refinement and consolidation of codes and categories generated up to that moment (see

Figure 1). During the subsequent collection of new data, codes and tentative categories not initially considered, were incorporated and tested through a constant comparison process. As such, data analysis was an iterative process in which the three coding profiles were permanently considered. Additionally, throughout the analysis, memos were written to reflect the ideas developed during the data analysis process (see

Figure 2). In this sense, the memos helped to keep trace of the process of data analysis, as well as of relevant evidence for the presentation of findings. A diagrammatic representation of the process of data analysis is shown in

Figure 3.

3. Results

The analysis yielded the construction of four categories that provide insights on the interests that social researchers possess when they share research data. These categories are: (1) selectively sharing, (2) perpetuating the system, (3) protecting privacy and (4) considering resources.

Table 1 shows these categories.

What follows describes each category and their distinctive features based on the testimonies of the twelve interviewees.

3.1. Selectively Sharing

Selectively sharing reflects the idea that social scientists are willing to share their research data in a circumscribed manner, that is, to individuals who are chosen by them. The factors social researchers consider when deciding who to share information with are trust, collaboration, and data usage. When researchers share selectively, they feel that control over the data is preserved by them to ensure that the right people will have access to the right data, and that these data will be used for appropriate purposes. By doing so, social researchers minimize their concerns about the negative consequences that could arise from unwanted people using the data or from using the data for non-academic purposes. This means, however, that only a restricted set of individuals can use the data, and that these data are often shared informally.

3.1.1. Trust

Selectively sharing requires that there must be a component of trust between the researchers and the recipient of the data. In this context, trust is defined as the belief that the recipient is honest, sincere and a close collaborator so that he would not misuse the shared data. As stated by one of the interviewees, “There must be a good openness from the researchers, and also a lot of trust” (# 5). This trust is generally developed during previous and ongoing collaborations. The following answer of a researcher when asked who he shares data with emphasizes this aspect, “Yes, with my brothers. I have no problem with sharing my data with them because we have worked very closely and besides, there is a lot of trust” (# 1). Similarly, another researcher pointed out, “If you ask me with whom I have shared my research data, I would tell you that with those whom I have a lot of confidence and those who have requested me to share my data. With no one else” (# 3). Together, this evidence shows that the greater the familiarity between the sharer and the recipient, the greater their willingness to share research data.

This criterion of trust includes students as well. First, sharing research data with students has teaching purposes, as indicated by one of the participants, “I sometimes work in a State with its municipalities while my students work with other States during their thesis work, if they were to ask me for the data, I would have no problem to share the data with them” (# 10). Second, data is shared with students to help them in their research. A testimony of a social researcher reflects this idea. “Teachers have a handful resource with their students and therefore I share everything with them. To speed up their work” (# 12). In short, sharing data with trusted people including students contributes to making teaching and learning processes more efficient.

Third, research groups are environments that foster trust among researchers to share their research data. These groups are generally conformed by researchers and students. The evidence of this study suggests that when knowledge and trust exist between the members of a research group, every member of the group has the right to use the data that the group generates. In this regard, the leader of a research group mentioned, “As we belong to the same research group, researchers and students are aware that the data they obtain can be used by anyone” (# 5). Likewise, within research groups, each member has specific intellectual interests, such that in a way, sharing research data is easier; as expressed by an interviewee, “There is a research database to which each area has access to. So, if someone needs data from this database, they even do not have to ask me, if they have access to the database, they can use the data to publish” (# 7). This makes sense when research groups generate large amounts of data. Regarding this, a social scientist, head of research group declared, “There really is so much to do, so much to write. So, if the information is there, it is for whoever wants it” (# 4). Thus, the structure and composition of research groups make it easier for research data to be shared.

However, when trust is absent, social scientists tend to hide their research data. This occurs when researchers are not members of the same research group and when there are disputes between them, as suggested in the following comment, “If you are not part of the research group, I will not share my data with you, no matter how much my data can contribute to your research” (# 6). The findings also show that mistrust increases when research data is used for a purpose other than the one agreed upon, as the following comment shows “It is complicated because unfortunately, the recipients of my data tell me how they will use the data, and they end up using them for something else, so trust between researchers is not very open” (# 9). Similarly, another interviewee sincerely expressed his lack of trust to share research data with certain individuals, “Because I do not trust them. There are people in whom I fully distrust (…) who behave unethically. I know people who could misuse that data” (# 3). To conclude, the absence of trust is a decisive reason that negatively influences the interest of researchers to share social research data.

3.1.2. Collaboration

Social science researchers show interest in sharing research data to generate and consolidate collaborations. A researcher expressed how co-authoring scientific papers can favor openness in research data. Similarly, the interviewees consider that those who collaborate with, are researchers that belong to the same research group. This is pointed out by one of the participants, “I have shared some data (…) with colleagues with whom I am working with in a team, or with colleagues with whom I am going to write a paper, so if I have data that can contribute to that goal, I share them” (# 6). Furthermore, the same researcher recognizes, although hesitant, that in such cases, she expects some recognition, “If I am part of the team that generated the data I would expect to become a co-author. Or if the work is part of a research group then I could get the credit, right?” (# 6). In short, sharing research data to enhance collaborations and publish research papers is a common practice among researchers.

Social scientists are aware that sharing research data enriches collaborations. Several of the interviewees agree with the following idea mentioned by one researcher, “When I write a scientific article, I invite someone to write with me who I know masters the subject and can contribute. In these cases, I share my databases with those people” (# 3). A similar expectation was expressed by another researcher who is not used to sharing. “I would like to share with those equally interested in this topic and those who can contribute with new ideas” (# 8). In addition, the sharing and availability of research data is also seen as a trigger for future collaborations. “If I have some data that address interesting topics, and I share them with someone, that person may trust me, and probably would say: …, your data are good, why don’t we work together? (…). That would make it easier to collaborate or do something together” (# 1). In conclusion, the interest to enhancing the quality of collaborations encourages the exchange of data among social researchers.

3.1.3. Data Use

For social researchers, it is important to know the use people will give to the data that is shared; in fact, proper use of research data is a condition for sharing. Regarding this, a scientist expressed, “I do not think that the problem is to share data. The problem is how these data are used. (…) I would share my data to whoever I know is going to use them in a proper way… The problem is whether the person who is going to use them, will do it correctly, ethically and with good intention” (# 3). Similarly, a researcher in economics answered the following when asked about his willingness to share research data openly, “It depends on the person who is going to use them, and how he is going to use the data. In which context is he going to use them? … It depends on the use you are going to give them” (# 7). These comments show that researchers are willing to share their data if there is certainty that the data will be used correctly; this looks more important than the advancement of knowledge that can be derived from sharing research data. On this, a participant pointed out, “Selfishly, I think that it has to do with knowing that the data will be used appropriately by the right person, given that it cost me a lot to collect these data. If that is going to impact upon science, that is good, but that is not my priority” (# 3). These attitudes bring with them risks associated with the fact that the data that are shared can be misused. When this occurs, it may happen that those initially willing to share data, decide to stop sharing as the data would not be enjoyed as initially expected.

This criterion of proper use of data serves as a mechanism to avoid risks associated with the mishandling of data, either because they are taken out of context or used for purposes other than those originally agreed. In this regard, a researcher said, “I believe that the information that I share can be misused (…) or can be put in a different context.” (# 4). Likewise, another participant stated, “I need to know that the data are not going to be misinterpreted, taken out of context, or used for another purpose than research” (# 6). However, the criterion of proper use seems to be relative, as it depends on personal interests, “I would not give the data to colleagues that say that the social economy should not exist and that there is no theory related to it (...) on the other hand, if colleagues who are promoting the concept of social economy asked me for the data, I would share the data with them; especially if those colleagues belong to my group, I would share the data more easily with them” (# 5). This suggests that knowing the potential use of research data that are shared would allow preventing their misuse, but at the same time, there is the risk that its distribution may be subject to potential arbitrariness. Moreover, it would be plausible to suggest that social researchers could expect from the recipients of data to pass a litmus test before gaining access to their data. This, though, contests the principles of Open Science, as it suggests that research data have private ownership.

3.2. Perpetuating the System

Perpetuating the system means that sharing research data is influenced by the inclination of social scientists to respect the socially established order in their context. The treatment that researchers give to research data is governed by the obligations that they must comply with, the routines embedded in their working practices, and the role research data play in the process of scientific inquiry. When perpetuating the system, social scientists feel that it is not mandatory to share research data because they are acting in accordance with what is institutionally established; they are complying with what the members of the community and their institution expect from them. Therefore, by perpetuating the system, social researchers are not upset about not sharing data. Researchers focus on carrying out the activities that they must contractually comply with, on performing their traditional research practices, as well as on reflecting on the role played by the data that can be shared.

3.2.1. Obligation

Perpetuating the system encourages researchers to fulfill the obligations that their institutions demand from them. Consequently, sharing research data is not an obligation for social scientists, since neither their institution nor the government agencies in charge of promoting the development of science and technology (CONACYT in the case of Mexico) have guidelines that require sharing research data. Regarding this, one interviewee mentioned, “I think that I am not obliged to do it. The postgraduate study regulations of my institution do not require me to do that. The institution does not tell me I have to do that. CONACYT does not tell me that I must do it” (# 3). Furthermore, researchers conceive that their duties have to do with teaching, supervising, having projects and using data to publish papers. In this regard, when a researcher was asked if sharing research data was an obligation, he replied, “My obligations are teaching, supervising students, and participating in the initiatives that we have, right?” (#1). There are also researchers who would like to share research data, but whose responsibilities do not allow them to do so, “I would like to share more. Some colleagues have asked me for information that I have not been able to share with them, but I would like to do it (...), but I have to pay attention to my students, that is why I cannot” (# 5). In sum, the evidence shows that researchers do not see sharing research data as one of their duties.

Conversely, some researchers are aware that, although it is not an obligation to share their data openly, they would be morally obliged since the research they carry out is financed with public resources, and therefore the data should be available. On this, various participants echoed the following opinion, “Should I share my data? (…) I believe that, to a certain extent, yes, because these projects are financed with public resources, so, yes” (# 7). Some researchers would agree that if there were guidelines institutionally established that require researchers to share their data, they would do so because there would be no alternative. In relation to this, an interviewee expressed, “If my institution would pronounce a policy to promote research data sharing, I would have no problem. I would not have an alternative, despite my thought, I would have to share” (# 3). Furthermore, if sharing research data were institutionalized, researchers would do so with less resistance since everyone would participate. Regarding this, a researcher expressed, “I think that it is not an individual issue, (…) there must be institutional rules of the game” (# 12). In addition, another participant stated, “It would be easier for me, if it is an institutional initiative. I do believe that if I see that several of my colleagues do that (…) I would incorporate this practice without any problem” (# 3). In conclusion, if institutional guidelines are in place to sanction not sharing research data openly, social scientists would be involved in their compliance.

Nevertheless, implementing guidelines that oblige scientists to share their data could have negative unintended consequences. Researchers may be uncomfortable with performing a new practice to which they are not used to. In turn, this could threaten the productivity of researchers in terms of publications, as they would be required to manage their data in order to openly share them. Similarly, some researchers would reject the idea of sharing as doing so could evidence the low quality of their data. Others would share part of their data in order to comply with the new regulation but keeping for themselves those valuable data to support their publications. After all, it would be a challenge for their university or CONACYT to verify that all data generated with public funds are shared. Moreover, the social scientists interviewed in this study know in advance that their position as researchers would not be at risk by simply not sharing their data. If that were the case, they could opt for not financing their projects with public funds if data sharing were mandatory.

3.2.2. Custom

Perpetuating the system causes social researchers to behave in accordance with the traditional practices of the community to which they belong. For social scientists, sharing research data is not a practice that they are used to carrying out; thus, they do not see it as a daily part of their work. In this regard, a social scientist mentioned, “I never think about sharing..., what I mean is that it is not in my mind if I am going to share or not. I had never thought about it” (# 7). Similarly, another participant said that the existing scientific culture does not encourage the sharing of research data, “If the scientific institution and the dominant culture of science do not promote the sharing of data, it will hardly be in the interest of researchers (...) If scientific institutions do not require researchers to share their data, one does not even think about it” (# 2). These testimonies show that researchers are not used to sharing, as one participant points out, “If someone asks me to share my data, I will share it (…), but in general we are not used to share” (# 11). In the same way, a scientist declared “I believe that it is not sufficiently internalized in the academic environment (...) At least the one I am in, sharing research data is not a common practice among my colleagues” (# 6). In short, the habit of openly sharing research data is not incorporated into the researchers´ way of acting and thinking.

The findings also show the fact that if some researchers share their data, others are positively influenced to do it. Regarding this, a scientist pointed out, “I think one must see the advantages because it would not be nice that I share my data and that nobody else does it. I would be willing to share if, and only if, most researchers did” (# 3). Conversely, research papers, reports, congresses, and internet sites are the usual mechanisms in which data can be shared, since relevant data is captured in these media. About this, an interviewee expressed, “You do not even ask yourself whether it is necessary to share the data (…) I believe that what the researcher shares is what he publishes, and once published, it becomes open” (# 2). Similarly, one participant said, “I don’t know if I feel that I have an obligation to share my data, but rather, to use them to generate knowledge through publications” (# 1). Social researchers also pointed out that, if they had to share their data, they would do it once benefits have been gained, since the norm is that the one who collects the data is the one that publishes first. Various scientists agreed with the following testimony, “It would be very complicated to share my data before getting a paper published, it would not be adequate (...) my point is that nobody is going to give you their data before they get to publish something with those data” (# 12). To conclude, the usual way researchers act mediates their interest to opening their research data.

3.2.3. Role of Data

Perpetuating the system influences how social researchers conceive the role of data in scientific inquiry. Some agree that sharing research data has the potential to generate new knowledge as datasets could be analyzed with theories, methods or techniques other than those originally used. About this, a researcher said, “It is information that you can look at it from one perspective and generate certain knowledge, but if you look at it from another perspective, it can serve to generate different knowledge” (# 6). Similarly, one of his colleagues stated, “Our training, our perspective, our research objective led us to see something within these data, but with different eyes. Having another training, another research objective, can lead you to see something else on the same data” (# 2). This allows other social scientists to take advantage of them, as well as to extend the lifetime of research data.

However, the usefulness of research data can also be questioned, particularly when data were collected within a specific research question, objective or methodological design. On this, several participants agreed with this testimony, “I cannot understand the usefulness of my interviews that already have a reason, they were created following a particular methodology, with a research object, and are associated with my own interpretation, perhaps with my training, and my research interest” (# 2). Therefore, researchers point out that research data would be only useful for those who work on the same topics. In this regard, one interviewee said, “Possibly if others are doing research on these topics, these data will be useful, but if not, I do not think so” (# 3). Similarly, the lack of usefulness of data might increase due to the contextual richness that some data collection techniques provide. Regarding this, a doctor in economics answered, “The databases can be shared, but this part (the context) that enriches the research would be lost. So, even if the databases are shared, important information would be lost” (# 7). In other words, there is a presumption among social researchers that data sharing has limited potential.

3.3. Protecting Privacy

Protecting privacy suggests that social scientists must protect their research data because they contain sensitive information that researchers must keep confidential due to confidentiality agreements previously established. When protecting privacy, researchers feel that it is convenient not to share their research data because they possess sensitive information about other individuals, such that they must respect the integrity of those who trusted them to share their experiences and viewpoints. By protecting privacy, researchers have a legitimate reason not to openly share research data as there might be harmful consequences for them or for those who participated in their research. As such, protecting privacy provides scientists with the certainty that the data they possess will not be used for purposes other than those originally agreed, allowing researchers to retain control over them.

3.3.1. Sensitive Information

Protecting the privacy of data means that the sensitivity of the data must be considered when openly sharing data. Sensitivity is associated with the care that research data requires by its nature, given that in social research, scientists tend to generate sensitive information related to human beings, as evidenced in the following comment, “As it is mostly personal data, or even confidential coming from the interviewees or those involved in your research, it is clear that these data are sensitive in terms of handling them, right? Because you are not talking about numbers” (# 6). The above comment shows a limitation to share research data, because according to social science researchers, unlike other areas of knowledge, the data they have contains confidential information of those involved in their research. In this regard, an interviewee expressed, “In basic sciences, engineering, and biology, where the quantitative tradition is commonly used, researchers are more prone to share their data. But in social sciences, we use the qualitative approach, which makes it more difficult to share data because they are associated with people’s identities” (# 2). For this reason, in the social sciences, scientific data is usually kept confidential.

Social scientists consider the qualitative techniques they use to collect data to have the virtue of deepening the intimacy of individuals. This happens when techniques such as life history and interviews are used, as shown by the following comment (when using quantitative data), “You get the data, you process them with a model, an econometric model and that’s it (...) however, when you use interviews, you require much more sensitivity to treat and disseminate your data” (# 12). In the same way, an interviewee stated the following, “We chose the life story to collect data in our research because it is precisely about the person and his identity, his personality (…) So, we are going to share the data to the extent that, from our viewpoint, it does not compromise the integrity of the informant or his or her own interests” (# 2). In sum, the nature of the information generated with qualitative techniques becomes problematic when it comes to sharing research data in the social sciences; hence, in disciplines with a quantitative tradition, it is more common to observe this practice.

3.3.2. Compliance with Agreements

Along the same lines, protecting privacy is associated with complying with the confidentiality agreements previously established between social scientists and their informants. In social research, researchers tend to ensure confidentiality to people who offer testimonies, as one participant stated, “The principle of confidentiality of our informants must be taken seriously and we should be extremely rigorous and careful not to use information that may hurt susceptibilities” (# 12). Thus, these agreements prevent sharing research data with others as it represents a betrayal of the participant’s trust and may have legal consequences. In this regard, an investigator said, “It is a similar situation with journalists, you cannot ask them to give you their source, right? I have a deal with my informants and if there is any moral or criminal damage due to the information that is used, the participant can sue me because I signed a confidentiality agreement” (# 11). The evidence shows that social scientists are used to abiding by the agreements they reach with those who participate in their research.

The researchers interviewed tend to guarantee that the data they collect will be used for academic purposes and that the identity of research participants will be protected. Furthermore, this is generally declared in a document. On this, a participant pointed out, “Part of the informed consent signed by research participants has to do with asking participants if we can use their information for academic and research purposes” (# 4). The above also prevents the data from being used for commercial purposes as stated by a scientist, “I have been asked by my students to share my data, but their intention is to use them to create companies, not to do research, and therefore I do not share that information” (# 5). In addition, researchers are clear that, if someone requests their data, researchers would first request their informants´ authorization to share them. Regarding this, a researcher said, “The authorization of the person participating in the interview would have to be requested to see if he or she wants to contribute with his interview to be used by another researcher (...) there should be permission to use that” (# 9). In conclusion, social scientists show awareness of the responsibility to protect the data they gather in their work.

3.4. Considering Resources

Considering resources implies that social researchers pay attention to the resources available to openly share research data. The resources have to do with time, effort, and institutional support. When considering resources, social scientists argue that they do not have the time, nor the institutional support required to share research data. Moreover, they also think that curating the data to further share them requires too much effort. Overall, the category of considering resources helps illustrate how researchers justify their decisions against proactively sharing scientific data. This justification gives them the opportunity to focus on other activities.

3.4.1. Time

Considering resources highlights the lack of time of researchers to share research data. While they are aware that data sharing can make the processes of science more efficient, researchers consider it to be time-consuming, as one testimony revealed, “Imagine if we all shared our data, that all research data were well organized, you would save a lot of time. (…) But, on the other hand, I feel that it would take more time for the researcher to prepare the data to further share them in the format in which journals request it” (# 1). As this comment suggests, social scientists prefer to be involved in activities that they consider more important. In relation to this, a researcher who coordinates different research projects pointed out, “I prefer a project (…) I prefer being involved four days [to work on a project] than to curate my data” (# 5). In the same way, another interviewee expressed the following, in relation to sharing data during the publication process, “I was uploading the paper and I suddenly read, share your data here. I said: I am not going to worry about that, I am not going to waste my time on this right now, what if the paper gets rejected? I might worry when the paper is accepted. If it gets published, I will gladly invest my time to curate my data. For now, I skip that step” (# 7). In short, from the perspective of social scientists, it is not worth investing the available time they have in sharing research data.

3.4.2. Effort

Considering resources means for social scientists to reflect on the effort required to share research data. For researchers, this effort not only relates to the effort required to share, but also to the effort involved to collect the data. Regarding this, an interviewee said, “I think there should be a good reason to share your data, because it takes a lot of work to collect them and analyze them” (# 3). This seems to suggest that the effort involved to collect and curate data is too much when compared to the benefits that can be obtained. In relation to this, a scientist emphasized, “Not everyone is willing to curate the information, I work with many colleagues who are not interested in curating the information, they want to use it, but not to curate it (...) because sometimes curating means a lot of work that is undervalued” (# 5). This especially occurs in scientific communities that do not value the collection, curation, and sharing of research data. In this regard, the assertion of a researcher was illustrative, “The academic system insists that, in order to be productive, you need to publish. You cannot tell the institution, look, I’ve already created these databases and I want to share them, right? Do you want to share them? Ok, you should know that it is not worth at all if you share them” (# 12). As such, researchers are in favor with the idea that those who contribute by sharing research data must receive some recognition. On this, an interviewee suggested, “I believe that those who obtain and curate the data should be recognized, surely more than it is now” (# 5). To conclude, researchers perceive that the work that entails collecting, curating and sharing research data is greater in comparison to the recognition that social scientists receive for doing it.

3.4.3. Institutional Support

When social scientists perceived the existence of available resources to support data sharing, their perception of having institutional support was strong. One interviewee expressed, “As long as we do not have institutional support to do that (sharing research data), we will not do it because we have many other responsibilities” (# 1). The lack of time, and the effort required by researchers to share would not be a problem if researchers had personal support to curate the data. In relation to this, a scientist mentioned, “If I had an assistant, a researcher financed by CONACYT, or a junior researcher paid by my institution, all these activities of data sharing could be done, but since I do not have any of these (...) the truth is that I have not shared my research data” (# 5). Likewise, a researcher declared, “You can spread the content of the transcribed interview because it is good, let’s say, in this case I should have someone to help me with the transcriptions so that interviews can be shared with no problem” (# 10). Additionally, as part of the institutional support, the existence of virtual spaces in which data can be deposited is also considered by researchers. On this, one participant said, “Well, if there is not a specific institutional area that tells you, bring your research data here, so that we can publish them for the benefit of society, well, that does not happen” (# 2). In sum, the absence of institutional support to curate research data influences researchers´ intentions to share their datasets.

4. Discussion

The findings show that social scientists have different reasons that prevent them from sharing research data openly. First, there are no incentives that encourage a more proactive participation of researchers in the opening of data. Sharing research data should be a valuable practice that counts as part of the productivity of scientists, as is the publication of scientific papers (

Piwowar et al. 2008). Second, it is understandable that researchers decide to prioritize activities that, if not accomplished, can have detrimental consequences. For this reason, it would be important that universities and research centers establish guidelines that position the opening of data as a responsibility, as it occurs with teaching, supervising, publishing, and working on projects (

Fecher et al. 2015;

Wiley and Mischo 2016). Third, it is also understandable that social science researchers care about sharing data when these data are sensitive, such that it becomes difficult to share. This resonates with previous findings that emphasize that, in social sciences, there is a responsibility to maintain confidentiality agreements and anonymity of informants (

Choudhury et al. 2014;

Pitt and Tang 2013). In this regard, it is clear how the researchers interviewed in this study demonstrate respect to those who are informants in their research. However, the results also show that researchers prefer to have control over the data they generate, such that they can decide with whom to share their data, despite knowing that this attitude is incompatible with open research data.

In addition, following the constructivist grounded theory approach helped to achieve the goal of this paper. Although in its origins, the proponents of the CGT advocated a strictly inductive application of it, following a constructivist approach allowed incorporating and enriching the findings with pre-existing notions about the phenomenon under investigation. In addition, the method facilitated the processes of data collection, coding, and analysis, as it offered guidelines that favored its execution, as well as the preservation of an audit trail of the process. Similarly, the use of grounded theory promoted a proactive interaction between the authors of this paper and the data that support the findings of the study, since the application of the constant comparative analysis required commitment and dedication along the study. Then, the qualitative nature of the study provided the opportunity to deepening our understanding on the researchers´ perspectives and experiences in relation to sharing scientific data. As such, this study is valuable since the conceptual categories and the substantive theory emerged directly from the field of the scientific community.

Overall, the findings invite us to reflect on the relevance of open research data. In this regard, the participants of this work come from different areas, including those related to job creation, entrepreneurship, gender violence, care for the elderly, mobility, social economy, and public policy. These areas of research are socially relevant in the Mexican context, such that data sharing on these domains would not only contribute to a better understanding, but also to a search for pertinent solutions to these concerns of society. In addition, openly sharing data increases the chances that the benefits documented in the literature can be of local use. Especially in countries such as Mexico, the budget for science is minimal, and therefore sharing open research data would contribute in making the use of available resources more efficient (

Guadarrama Atrizco 2018). In the last year, various initiatives associated with the opening of data during the COVID-19 pandemic have revealed the scientific, health-related, and social benefits that sharing open research data can generate (

Díaz et al. 2021;

Zastrow 2020). Finally, a central argument of the supporters of open research data is that data must be available when their generation is financed with public resources (

Triggle and Triggle 2017). However, it is clear that the perception among the interviewees in this study is not yet sufficient for them to be actively involved in the opening of their research data.

It is therefore desirable to have a robust national legislation on Open Science, especially on the opening of research data. In Mexico, the approach has been primarily on promoting open access, obscuring other valuable research practices related to the opening of science (

Trujillo-Uribe 2017). Likewise, universities and research centers do not have guidelines or specialized areas to support the opening of scientific data (

Babini and Rovelli 2020). Contrary to what would be desirable, there is a tendency to promote schemes in which it is convenient for social scientists to hide information and to work individually to satisfy their own interests. Thus, it would be appropriate to learn from cases of Argentina or the United States, where there is a legal obligation to sharing research data when the research is financed with public resources, and in case of failing to do so, the researcher is sanctioned with the impossibility of receiving funding to carry out future investigations (

Domínguez et al. 2013;

NIH 2008;

NSF 2015). In addition, it is necessary to establish guidelines on how data in social sciences should be shared; especially those associated with individuals (

Cragin et al. 2010;

Jeng 2017). The opening of research data in social research needs special attention, as we cannot assume that data sharing in social sciences resembles how data sharing occurs in other areas of knowledge. Overall, what is essential, as the interviewees pointed out, is that institutions need to provide greater support to researchers, either by offering training programs to curate and share data, by creating awareness workshops to highlight the benefits of open research data, or by allocating trained staff to delegate these activities (

Fecher et al. 2015;

Prado and Marzal 2013). On this matter, libraries and their staff of the different academic institutions can play a fundamental role. Unfortunately, institutions rarely have specialized departments to support data sharing, besides the fact that sharing is not a priority for researchers.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that if we are to better understand the sharing of research data, different aspects must be taken into consideration. The study shows that in order to promote the opening of social research data, cultural, normative, and institutional concerns must be addressed. As such, this study is relevant because it shows that social scientists tend to carefully evaluate their decisions to openly share research data, including when these data are generated with public funds. Overall, the study shows that trust, availability of resources, obligations, routines, and personal interests shape social researchers´ decisions to openly share their research data.

Regarding the qualitative approach used in this research, the constructivist grounded theory method made it possible to delve into the attitudes of social science researchers to share their research data in a routine manner, as the literature suggests it is happening worldwide. Consequently, this research provides evidence that can be useful for institutions and individuals responsible for developing strategies and guidelines aimed at providing free access to scientific knowledge. In addition, the study stimulates to think carefully about the role of data in science, their dissemination, and the position that social researchers have on the matter. Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge that the findings of this study are limited to a small sample of participants; this, however, opens the discussion for future research to be conducted with a greater number of social researchers and institutions. This can potentially add to the findings of this study, by offering new conceptual categories that better explain the opening of research data. There is still much to come. The opening of data in the social sciences is an incipient practice in the Latin American context that requires more development and better understanding on the motivations, interests, incentives, and obstacles that shape researchers´ attitudes toward the openness of scientific data.