Women Architects in Portugal: Working in Colonial Africa before the Carnation Revolution (1950–1974)

Abstract

:1. Pioneering Women Architects in Africa

2. Maria Carlota Quintanilha’s Background

3. Maria Emilia Caria: Working at the Colonial Public Works department in the Portuguese Metropole

4. Quintanilha: Working in Colonial Mozambique

5. Final Considerations: Being a Woman Architect in Colonial Africa before the Revolution

Author Contributions

Funding

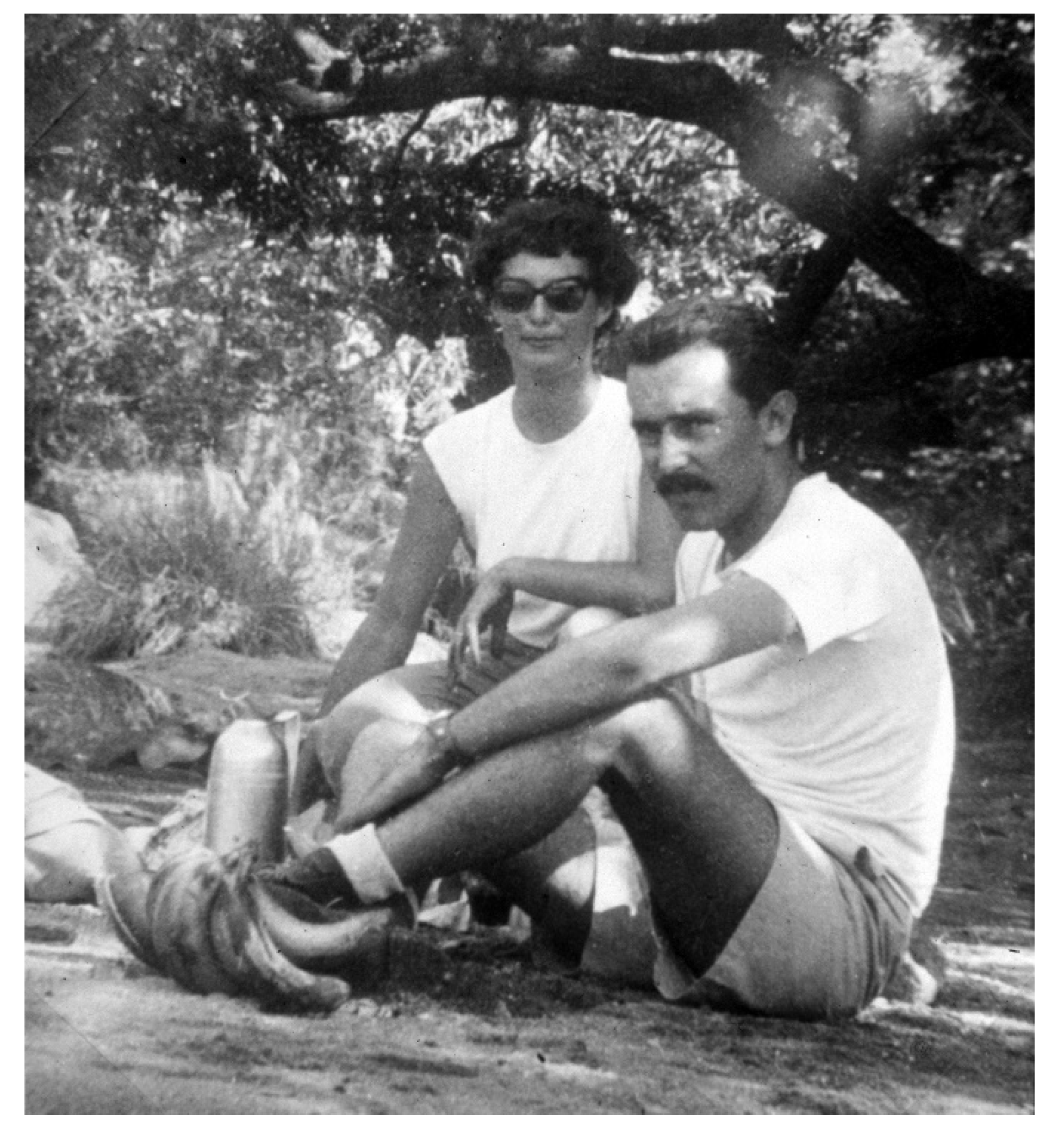

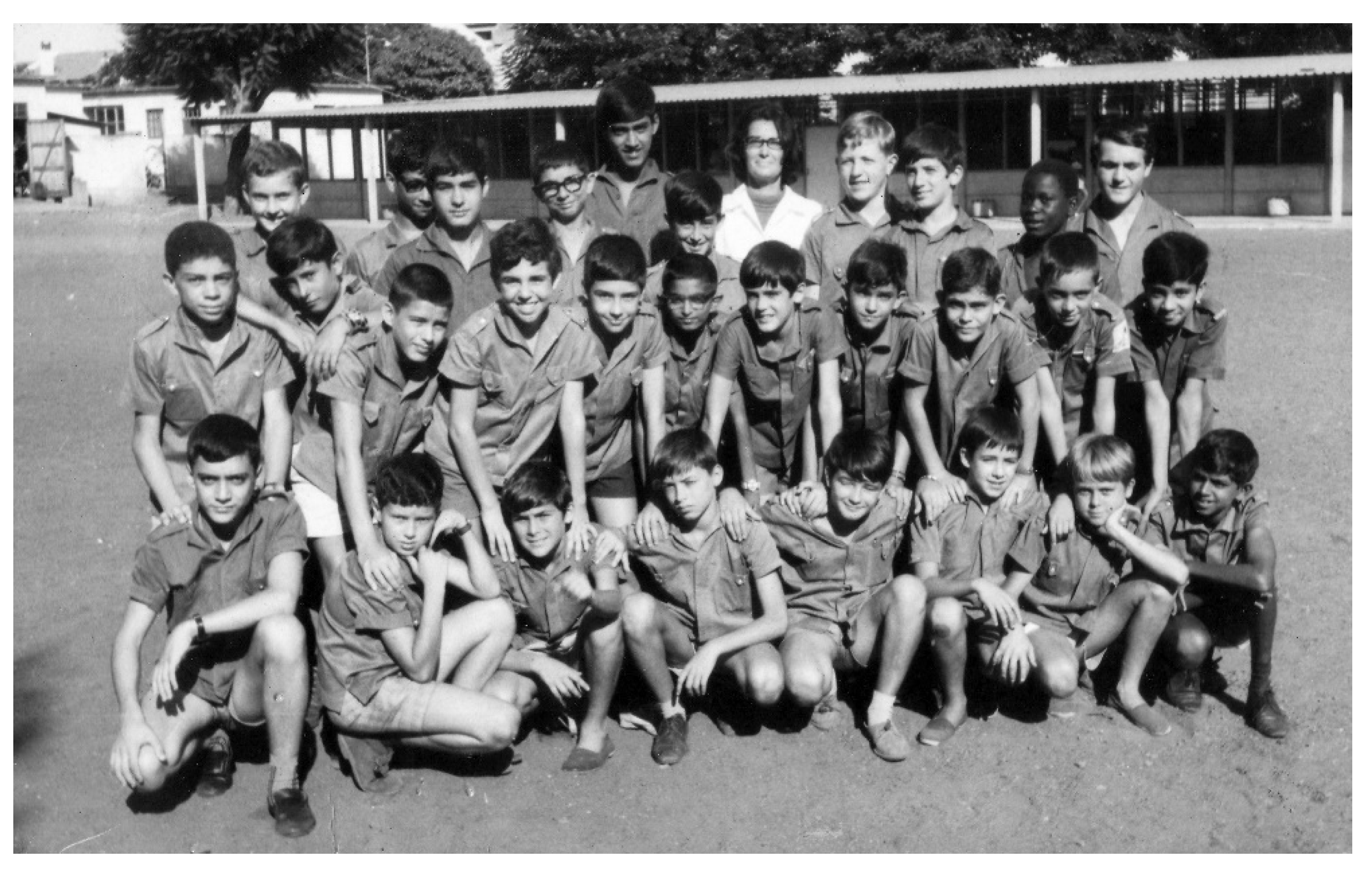

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comissão Instaladora. 2014. Dossier de Candidatura—Comissão Instaladora do Comité DOCOMOMO—Angola. Luanda: unpublished document (June). [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, José Manuel. 2002. Geração Africana: Arquitectura e Cidades em Angola e Moçambique, 1925–1975. Lisbon: Livros Horizonte. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Eduardo Jorge. 2010. A Escolha do Porto: Contributos para a Actualização de Uma Ideia de Escola. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade do Minho, Guimarães, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Figueira, Jorge. 2002. Escola do Porto: um Mapa Crítico. Coimbra: Edições do Departamento de Arquitectura da FCTUC, Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, Ana Isabel Arez de. 2015. Migrações do Moderno. Arquitectura na diáspora: Angola e Moçambique (1948–1975). Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Lusíada de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Milheiro, Ana Vaz. 2010. Bernardino Ramalhete & Eduardo Naia Marques, os arquitectos da opção empresarial. In JA–Jornal Arquitectos, Ser Independente. N. 240. Lisbon: Ordem dos Arquitectos, pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Milheiro, Ana Vaz. 2011. Maria Carlota Quintanilha: Uma Arquitecta em África. In Jornal Arquitectos: Ser Mulher. N. 242. Lisbon: Ordem dos Arquitectos, pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Milheiro, Ana Vaz. 2012. Nos Trópicos Sem Le Corbusier: Arquitectura Luso-Africana no Estado Novo. Lisbon: Relógio d’Água. [Google Scholar]

- Milheiro, Ana Vaz. 2017. Arquitecturas Coloniais Africanas no fim do “Império Português”/African Colonial Architecture at the end of the “Portuguese Empire”. Lisbon: Relógio d’Água. [Google Scholar]

- Milheiro, Ana Vaz, Filipa Fiúza, Rogério V. Almeida, and Débora Félix. 2015. Radieuse Peripheries: A comparative study on middle-class housing in Luanda, Lisbon and Macao. In Middle-Class Housing in Perspective from Post-War Construction to Post-millennial Urban Landscape. Edited by Gaia Caramellino and Frederico Zanfi. Bern: Peter Lang Publishers, pp. 211–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mingas, Ângela. 2011. Mulher e Arquitectura em Angola. In Jornal Arquitectos: Ser Mulher. N. 242. Lisbon: Ordem dos Arquitectos, pp. 121–23. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, Elisiário José Vital. 2013. Liberdade Ortodoxia: Infraestruturas de Arquitectura Moderna em Moçambique (1951–1964). Ph.D. thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Moniz, Gonçalo Canto. 2011. O Ensino Moderno da Arquitectura A Reforma de 57 e as Escolas de Belas-Artes em Portugal (1931–1969). Ph.D. thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal. Vols 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, Irene Flunser. 2007. Estado Novo, as Mulheres e o Feminismo. In O Longo Caminho das Mulheres: Feminismos—80 Anos Depois, 2nd ed. Edited by Lígia Amâncio, Manuela Tavares, Teresa Joaquim and Teresa Sousa de Almeida. Lisbon: Publicações Dom Quixote, pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, Rita Cerqueira. 2013. Mundo Novo. Feminino Tropical: Maria Emília Caria e o Urbanismo no Ultramar. Master’s thesis, ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Quintanilha, Maria Carlota. 2011. Interview by Ana Vaz Milheiro and Ricardo Lima. Lisbon. June 13. [Google Scholar]

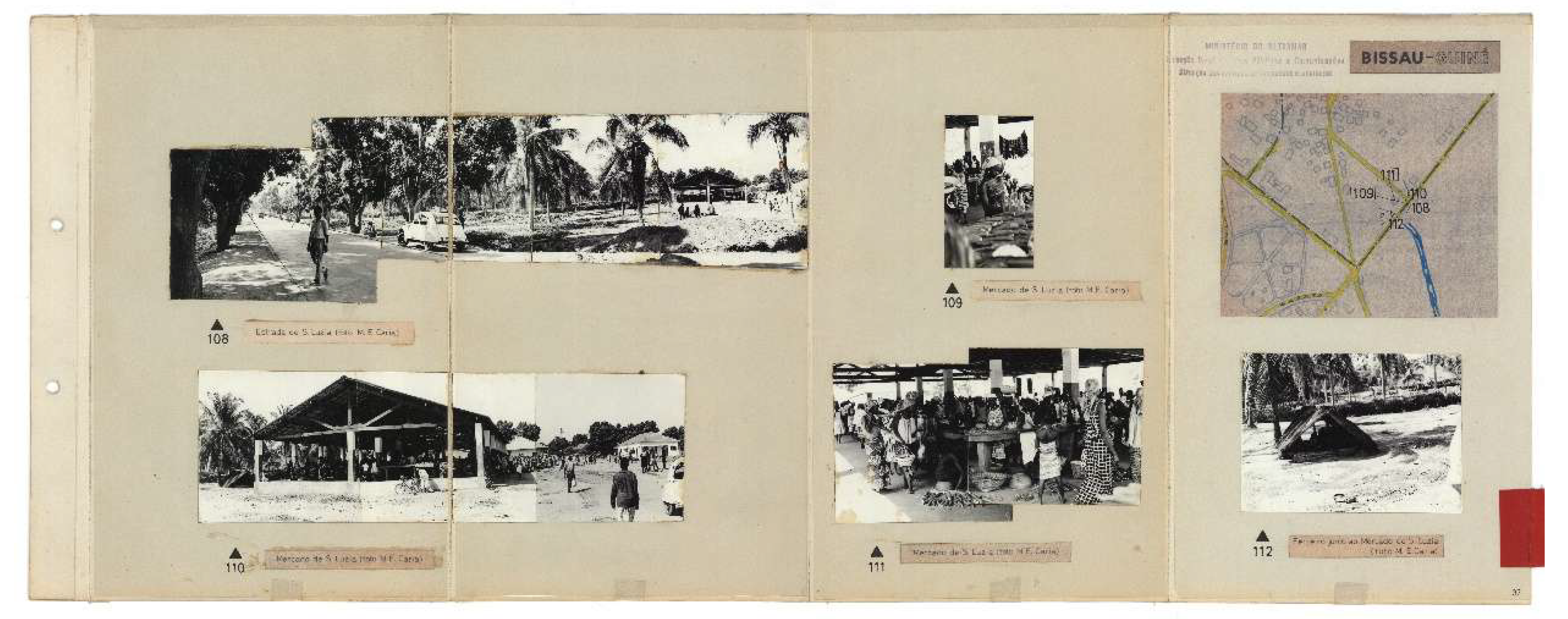

- Roxo, Joana Filipa. 2016. A Senhora Arquitecto: Maria José Estanco. Master’s thesis, ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Rudofsky, Bernard. 1964. Architecture Without Architects—A Short Introduction to Non-pedigreed Architecture. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Seabra, António Saragga. 2013. Interview by Rita Cerqueira Portela, for her Master Thesis. Lisbon. April 26. [Google Scholar]

- Sindicato Nacional dos Arquitectos. 1961. Arquitectura Popular em Portugal. Lisbon: SNA, vol. 1 e 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Manuela. 2011. Feminismos: Percursos e Desafios (1947–2007). Alfragide: Texto Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Tostões, Ana. 1997. Os Verdes Anos na Arquitectura Portuguesa dos Anos 50. Porto: FAUP Publicações. [Google Scholar]

- Tostões, Ana. 2014. Arquitetura Moderna em África: Angola e Moçambique. Lisbon: Caleidoscópio. [Google Scholar]

- Veloso, António Matos, José Manuel Fernandes, and Maria de Lurdes Janeiro. 2008. João José Tinoco: Arquitecturas em África. Lisbon: Livros Horizonte. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Estado Novo in Portugal was a political regime of Fascist inspiration that was to survive the Second World War and last until the Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974, with António de Oliveira Salazar as its principal ideologist. He governed the country up until 1968, two years before his death, and was succeeded by Marcelo Caetano. The end of the regime was also to advance the independence of the former Portuguese colonies in Africa (Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, Angola and Mozambique). The independence processes were completed by the end of 1975. |

| 2 | The period of the First Republic in Portugal, which spanned the years 1910 to 1926, was one of opening-up for the country, particularly with reference to the suffragette movements. This reformative spirit, however, always clashed with the political and economic difficulties the Republican regime had to deal with, a situation that would eventually lead to its demise. |

| 3 | The liberation struggles against the Portuguese colonial regime began in Angola (1961), and spread to Portuguese Guinea in 1963 and Mozambique in 1964. The strategies adopted by the regime to minimise the impact of the colonial wars included investment in construction projects financed by the state and the private sector. Architects benefitted from the many commissions for new designs. |

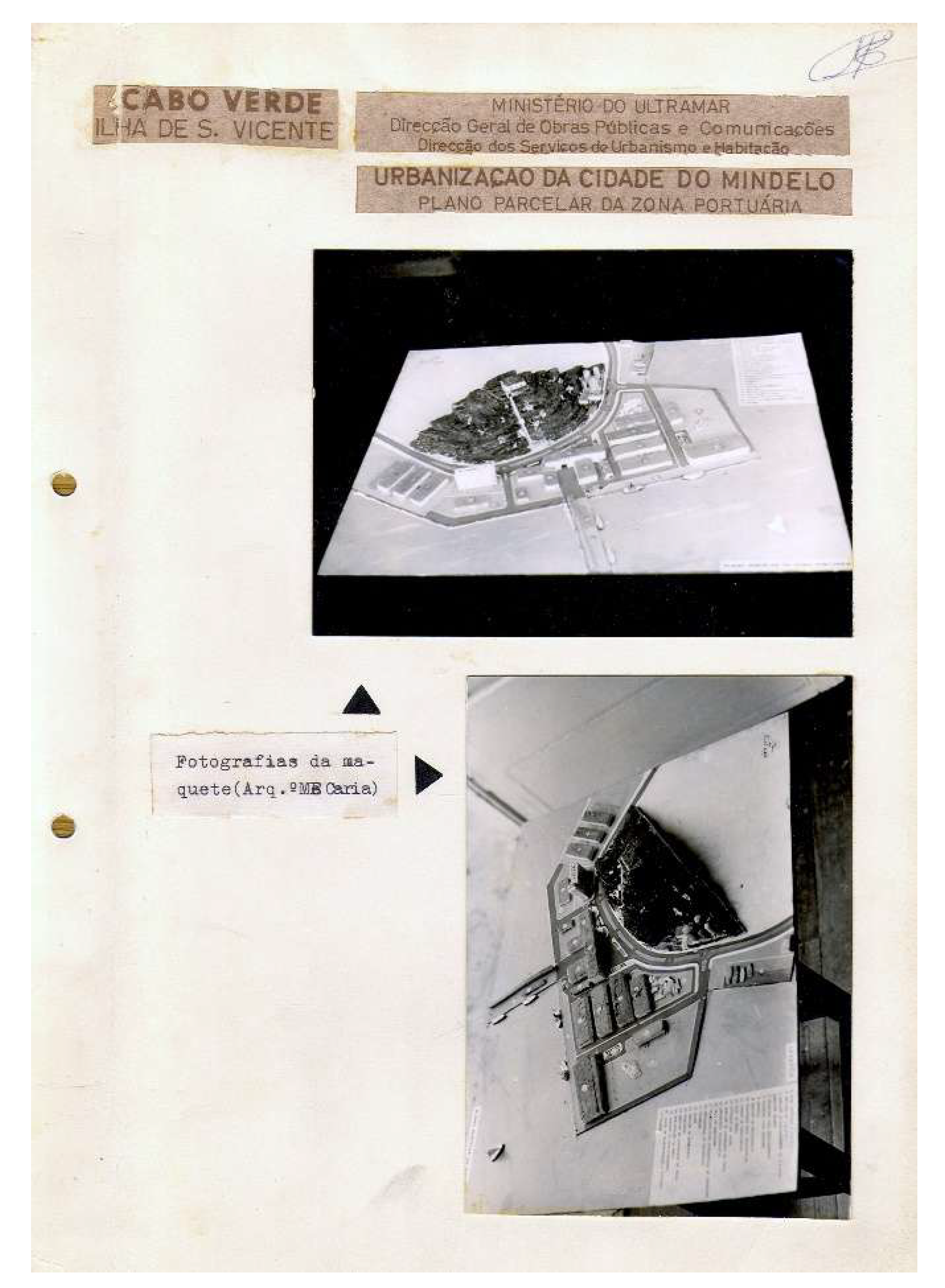

| 4 | “At the Lisbon School, women were not well tolerated. Some teachers falsified grades in order to prevent women students from being successful. This happened to me” (Quintanilha interviewed by Milheiro and Lima, 13 June 2011). |

| 5 | Maria José Marques da Silva’s father was the architect José Marques da Silva (1869–1947), who also trained in Porto and cultivated architectural eclecticism. |

| 6 | Jacinto was the daughter of European settlers and became an architect in 1956; she worked in Angola until 1959. She was responsible for several important modern urban development plans and buildings, such as the High School in the then small town of Henrique de Carvalho (present-day Saurimo, Lunda Sul, 1958–1959, designed with her husband, the architect Francisco Silva Dias). |

| 7 | Ana Herminia Vilarigues Simões Torres was born in Dondo (Kwanza Norte, Angola) in 1945 and died in 2006. She graduated in Architecture from the Lisbon School of Fine Arts during the colonial period. Upon her return to Angola, she worked with the architect Vasco Vieira da Costa (1911–1982), a reference figure in the modern culture of the country. After independence in 1975, Torres took on active roles in prominent positions in various Angolan Public Works departments (Comissão Instaladora 2014; Mingas 2011). |

| 8 | GAUD was managed by the architects Bernardino Ramalhete (1921–2018) and Eduardo Escudeiro da Naia Marques, born in 1935 (Milheiro 2010). The references to the architect Leonor Figueira were made by Naia Marques in interviews conducted by A.V. Milheiro in 2010 (ibid.). |

| 9 | It was not possible to determine exactly when the two architects attended the Lisbon School of Fine Arts, though there are official reports. However, we believe Quintanilha began her studies in 1944/1945, as informed to us by a former classmate—Maria Antónia Roque Gameiro Martins Barata Cabral interviewed by Leonor Matos Silva—and she is recorded in photographs of the time (see Figure 2). In Caria’s case, we are also unable to give the exact date of her graduation. To better understand the architecture education system in Portugal in the period when Quintanilha and Caria studied in Lisbon and Porto, its differences and affinities, see (Moniz 2011). |

| 10 | Quintanilha met her future husband, the architect João José Tinoco, at the Porto School, and they married shortly before they left for Portuguese Africa. Caria started dating an electrical engineer during one of her official missions to Cape Verde in the early 1960s. After her marriage, her full name became Maria Emília Caria de Melo. Her husband was 30 years older than her (Seabra 2013). |

| 11 | “Maria Emilia Caria was an urban planner (…). She had learned the métier with the engineer Eurico Machado, at the Office already. He was also an uncompromising person, incapable of being corrupted (…). Working in urban planning often involves being exposed to corruption …” (Seabra interviewed by Portela, 26 April 2013). Machado was the director of the Council of Town Planning and Housing at the General Council for Public Works and Communications, a department of the Ministry of Overseas Affairs, where Caria worked after 1962. His biography has not yet been studied, however, and there is not much systematic information about the career of this civil engineer. Nevertheless, the influence of engineer Machado is often mentioned by former employees of this Colonial Public Works department. |

| 12 | The First National Congress of Architects, held in Lisbon in 1948, was a landmark in the history of Portuguese post-war architecture. Held at the insistence of the Estado Novo government, it was, however, used by architects of the younger generations as a means of affirming the principles of Modernism, which still met with resistance from the older architects. As it was dominated by the positions of the modern faction, the congress was to be recognised by Portuguese historians as a victory for the Modern Movement (Tostões 1997). |

| 13 | Moniz, in his study on the teaching of architecture in Portugal between 1930 and 1957, reinforces the idea that there was an assumed “resistance to the modern” in the mandate of the Portuguese architect Paulino Montez (1897–1988), as head of the Lisbon school from 1946 onwards (Moniz 2011). Montez worked mainly during the Estado Novo regime, having dedicated himself to teaching and urbanism. |

| 14 | The presence of Le Corbusier’s ideas in Portuguese architectural culture became progressively stronger after the dissemination in Portugal of some of his most important texts, particularly the full translation to Portuguese of the Corbusian version of the “Athens Charter” (1943), which appeared in 1948–1949 in the Portuguese magazine Arquitectura, which specialised in publishing architectural designs and articles on the métier (Milheiro 2012). The circulation of Le Corbusier’s ideas amongst the younger generations was to have an impact on architectural design practice, making modern architecture a common benchmark amongst professionals and leading it to become the standard from the 1950s onwards. |

| 15 | The crossing of the three art forms that traditionally made up the academic curriculum at the Portuguese Schools of Fine Arts—architecture, painting and sculpture—was deemed worthy of particular attention amongst Portuguese architects, in line with the currents coming from Brazilian architecture, which argued for the combination of the arts in architectural design. The debate in Portugal owed a lot to the third Meeting of the International Union of Architects (UIA) held in Lisbon 1953; it had a discussion session specifically devoted to his subject matter. The Conference was authorised by the Estado Novo regime in a phase of international openness in the wake of World War II. |

| 16 | A British planner who was much respected in Portugal. Abercrombie’s plans contributed to the consolidation of the British New Town movement, which was part of the post-war urban reconstruction policies in the United Kingdom. In Portugal, this planning current had an influence on the laying out of new neighbourhoods that were peripheral to the historic centres and were designed to house the new middle classes. In Angola, similar strategies were applied from the 1960s onwards, while still under the control of the Portuguese colonial government (Milheiro et al. 2015). |

| 17 | In the interview she gave us, Quintanilha stated that the date of her wedding was arranged to fit in with the couple’s plans to move to the African colonies. |

| 18 | As mentioned in footnote 1 above, the revolution of 25 April 1974 brought the dictatorial regime in Portugal to an end, and sped up the independence processes for the Portuguese African colonies. |

| 19 | In addition to his work in the service of the Brigade, where he worked on the Matala Dam (Magalhães 2015), of the works executed between 1953 and 1956, during his stay in Angola, the Biópio Power Station and two collective housing blocks in Sá da Bandeira (now Lubango) are the most commonly named. |

| 20 | The precarious conditions in which they lived in Angola had directly to do with the fact that they settled in the interior of the country, and lived essentially on construction sites. In the 1950s, large and middle-sized Angolan cities were experiencing rapid growth and began to have good education and health facilities. The country’s inland regions, however, did not have the same level of infrastructuring. This situation led Quintanilha to ask her father for support in finding an alternative in Lourenço Marques, a consolidated city that was then the capital of Mozambique. According to her own statements, Quintanilha enjoyed very much living in urban environments. |

| 21 | Quintanilha’s private life with Tinoco was a constant feature in the interviews she gave. The fact that the couple had a conflictual relationship was to have an effect on their professional relationship as co-designers of architectural works produced in the office in their home in Lourenço Marques. These conflictual situations were a matter of informal gossip amongst the neighbours, and thus became public knowledge as far as professional circles were concerned. One again, one should stress that this situation of conflict is only revealed in this article because of the level of importance it has in assessing Quintanilha in terms of the quality of her architectural work and the role she played. |

| 22 | Here we refer to the growing international renown of “organic architecture”, from the publication in 1945 of Verso un’architettura organica, by Bruno Zevi, which was translated to English five years later as Towards an Organic Architecture. Portuguese architects were also caught up in this new trend. Of Zevi’s works that are remembered well by Portuguese architects, mostly among those that were Porto-based, one can highlight Saper vedere l’architettura (1948) and Storia dell’architettura moderna (1955) (Fernandes 2010). |

| 23 | The main architectural firms in Lisbon and Porto paid considerable attention to international architecture, as confirmed by the books and magazines that made up most of the libraries in said offices. |

| 24 | From the 1950s onwards, debates around organic trends began to proliferate in the Portuguese schools, particularly on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto in Porto School (Figueira 2002; Fernandes 2010; Moniz 2011). |

| 25 | The architects Silva e Castro and Saragga Seabra were Maria Emília Caria’s colleagues at the Ministry of Overseas Affairs, who worked for the Council of Town Planning and Housing of the General Council for Public Works and Communications, which replaced the Overseas Planning Office after 1957. The Council’s work was characterised by taking into consideration aspects such as the local culture, traditional building systems and locally-sourceable materials. The architecture produced by the group revealed a greater understanding of the specificities of the places where the works were located, and of the socio-ethnographic characteristics of the resident populations (Milheiro 2017). |

| 26 | From 1957 onwards, Arquitectura magazine underwent a change in orientation and no longer favoured the architecture of the Modern Movement; in its stead it advocated for a regionally “more contextualised” architecture. This orientation was marked by special issues of the magazine devoted to these architects. |

| 27 | In 1955, Portuguese architects began work on a survey of Portuguese Regional Architecture, which was released in book form six years later under the title Arquitectura Popular em Portugal (Vernacular Architecture in Portugal). This inventory preceded Rudofsky’s book, Architecture without architects—A Short Introduction to Non-pedigreed Architecture (1964), and was to be a landmark reference for Portuguese architecture, introducing, as it did, a wide range of formal and technical solutions influenced by the vernacular culture. Whilst the inventory did not extend to the Portuguese colonies in Africa and Asia, missions to Guinea-Bissau and Timor were nevertheless carried out (Milheiro 2017). Maria Emília Caria was likewise to conduct surveys on African habitats in regions such as Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau. This article would argue that there is a relationship between the survey in the Portuguese metropole and the methods followed by Caria. |

| 28 | The purpose of Caria’s inventories was to gather material and information for the urban plans she was involved in drawing up. The surveys mentioned prior to Caria’s were carried out with the intention of them being published; and indeed, only that carried out in the Portuguese metropole was published. |

| 29 | The Council of Town Planning and Housing at the General Council for Public Works and Communications was a Colonial Public Works department from the Ministry of Overseas Affairs (Direcção de Serviços de Urbanização e Habitação da Direcção Geral de Obras Públicas e Comunicações do Ministério do Ultramar—DSUH/DGOPC-MU), based in Lisbon after 1957. It started out as the Colonial Planning Office (Gabinete de Urbanização Colonial—GUC), later became known as the Overseas Planning Office (Gabinete de Urbanização do Ultramar—GUU), and was set up by Marcelo Caetano, then Minister for the Colonies, in 1944. Caetano succeeded Salazar as the head of the Estado Novo in 1970. The office brought together a team of architects, engineers and other specialists from the fields of architecture and urban planning for the tropical regions that were responsible for urban plans and the design of public buildings (Milheiro 2012, 2017). |

| 30 | Besides their duties as civil servants working for the Ministry of Overseas Affairs, these architects often also worked at offices that operated in the region and could benefit from the local resources. |

| 31 | Cape Verde was one of the Portuguese African colonies that was poorest in natural resources; it was regularly beset by environmental calamities (such as droughts and volcanic eruptions) that had an adverse effect on farming harvests, which were the main source of food for the region. The cities were also very poorly equipped, even in comparison to Angolan and Mozambican cities of the same size. Chronic housing problems for all classes of colonial society were also part of the general scenario. All these aspects were identified by Caria in her reports, for which Figure 5 provides an example. |

| 32 | Conflicts between the specialists working for the Public Works departments in the Portuguese metropole, i.e., in Lisbon, as was the case for Caria, and the specialists in the field in Africa were common, and made the realisation of plans more difficult. |

| 33 | The complex nature of the relationships and dependencies between the metropole and the local governments, as well as the presence of colonial elites with their own political and economic interests, was also a source of conflict. |

| 34 | Caria’s technical capacity was proved in the oral testaments of her colleagues, as was her concern with the local populations, which, in these colonies in particular, often lived in buildings with poor conditions of habitability, and continued to have little access to medical care or education. Caria’s plans sought to close those gaps, and she incorporated public facilities that were not only designed for the European populations, or for civil service contingents, but also for native groups. |

| 35 | Salamansa was a fishing village next to the seaside resort of Baía das Gatas, the plans for which were drawn up between 1963 (the year of the first surveys) and 1973, under Caria’s responsibility (São Vicente island, Cape Verde). Her plan altered the approach previously devised for the General Council for Public Works and Communications by the architect António Sousa Mendes in 1958; Sousa Mendes left the Ministry of Overseas Affairs in 1961. One of the peculiar aspects of the existing documentation was the emphasis on the importance of visits to the site and of a survey of the new material for the drawing up of the new plan, in accordance with orientations by the then head of department, the engineer Eurico Machado (mentioned in note 11). Comparisons between the final designs from the late 1950s and Caria’s plan revealed a modernisation of the instruments of urban design, with the replacement of an “artistic” and all-inclusive design (of a culturalist nature) with the identification of sectors and demarcation of land division processes (thus showing a closer link to the social sciences). Please see, in the Overseas Historical Archives, “Plano de Urbanização da Baía das Gatas” [Urban Development Plan for Baía das Gatas], 1963–1972, cota/number: 2058/08218. |

| 36 | From this year onwards, and up until 1974, Caria’s plans for the Cape Verdean capital focused on the port area of Praia (capital of Cape Verde, Santiago island). |

| 37 | Praia traditionally occupied the “Achada Principal” only, so the city was somewhat restricted in terms of expansion. This led to a proliferation of buildings on the hill slopes and riverbeds (which were mostly dry, but prone to flooding in the rainy season). There was, therefore, a history of urban transgressions that Caria’s plan aimed to resolve by creating regulated urban planning mechanisms. By pointing out that only 27% of the city’s population lived in the central area, where most of the urban facilities and infrastructures were also concentrated, Caria sought to call attention to the precarious situation of the rest of the population who lived in non-urbanised areas. Please see, in the Overseas Historical Archives, “Urbanização da Cidade da Praia—Cabo Verde. Plano parcial da Achada Principal e Áreas adjacentes (Nova Área Central)” [Urban Development of City of Praia—Cape Verde. Partial Plan for the Main Plateau and Adjacent Areas (New Central Area)], cota/number: 2057/07898. |

| 38 | The plan for the town of Mindelo, then known as the third plan, was submitted to a committee of five consultants, all of them engineers. Recommendations were made and a new design was presented. These processes show both the level of scrutiny and the difficulties of going ahead with plans, even under a colonial regime dependent on decisions made in Lisbon, the capital of the “Empire”. Please see, in the Overseas Historical Archives, “Plano de urbanização do Mindelo, Ilha de S. Vicente”, 1970–1973 [Urban Development Plan for Mindelo, São Vicente island], cota/number: 2060/07216. |

| 39 | João José Tinoco, Quintanilha’s husband, was born in 1924 and died in 1983. He graduated in 1952 in Porto, after first having begun at the Lisbon School of Fine Arts, just like his wife. After their divorce, he continued to work in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo), founding the A121 architectural firm with António Matos Veloso and Octávio Rego Costa in 1972. He returned several times to Portugal in 1975 for health reasons, and two years later finally left Mozambique. In addition to the monograph dedicated to his work (Veloso et al. 2008), see also the biographical resumés in Miranda (2013, pp. 83–86) and Magalhães (2015, pp. 251–57). |

| 40 | Amongst the Mozambique-based architects who worked with the Quintanilha–Tinoco couple were António Matos Veloso, as already mentioned, and Alberto Soeiro (Veloso et al. 2008). |

| 41 | The ODAM group was set up in Porto in 1947, ahead of the First National Congress of Architects. Its main goal was to advocate for and propagate the ideals of modern architecture in Portugal, and call attention to the precarious conditions in which the population in general lived. |

| 42 | Such as Antonieta Jacinto, already mentioned above. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaz Milheiro, A.; Fiúza, F. Women Architects in Portugal: Working in Colonial Africa before the Carnation Revolution (1950–1974). Arts 2020, 9, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030086

Vaz Milheiro A, Fiúza F. Women Architects in Portugal: Working in Colonial Africa before the Carnation Revolution (1950–1974). Arts. 2020; 9(3):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030086

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaz Milheiro, Ana, and Filipa Fiúza. 2020. "Women Architects in Portugal: Working in Colonial Africa before the Carnation Revolution (1950–1974)" Arts 9, no. 3: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030086

APA StyleVaz Milheiro, A., & Fiúza, F. (2020). Women Architects in Portugal: Working in Colonial Africa before the Carnation Revolution (1950–1974). Arts, 9(3), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030086