Teresa Żarnower’s Mnemonic Desire for Defense of Warsaw: De-Montaging Photography

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Teresa Żarnower’s Paradigm Shift: From Sculpture to Photomontage

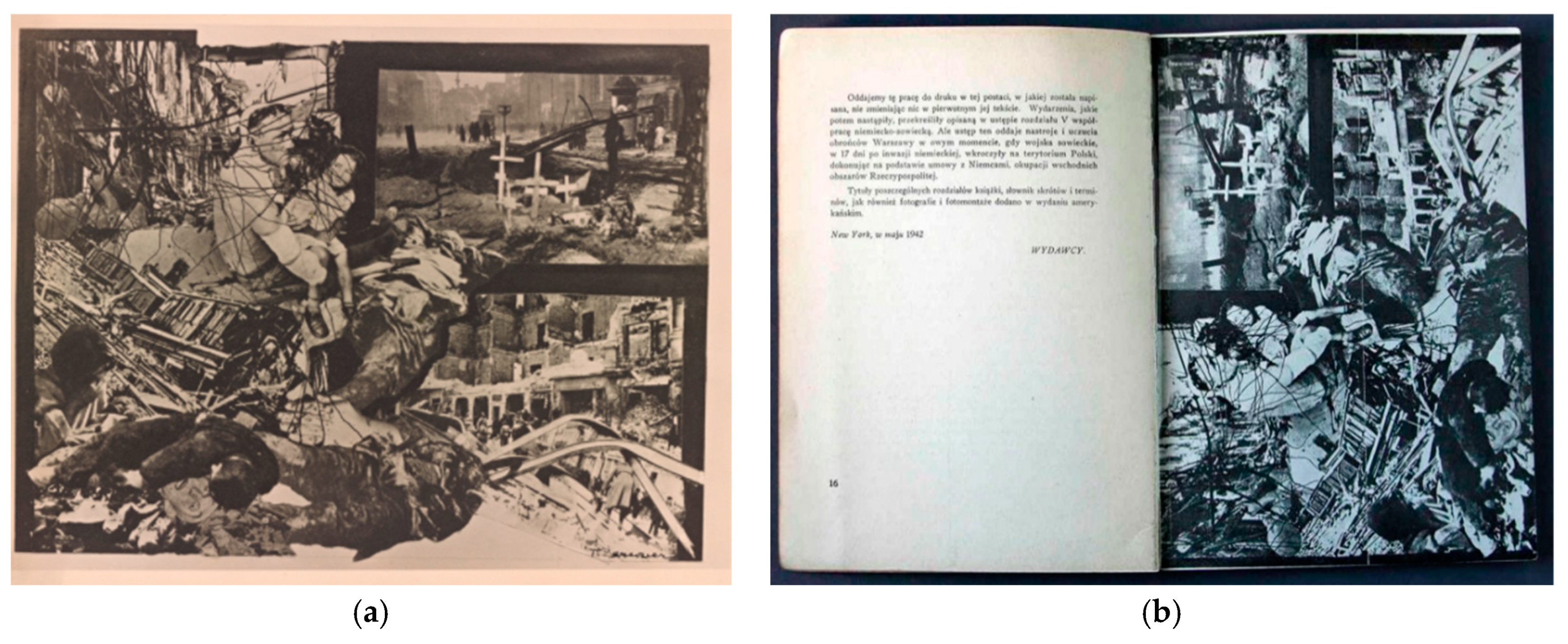

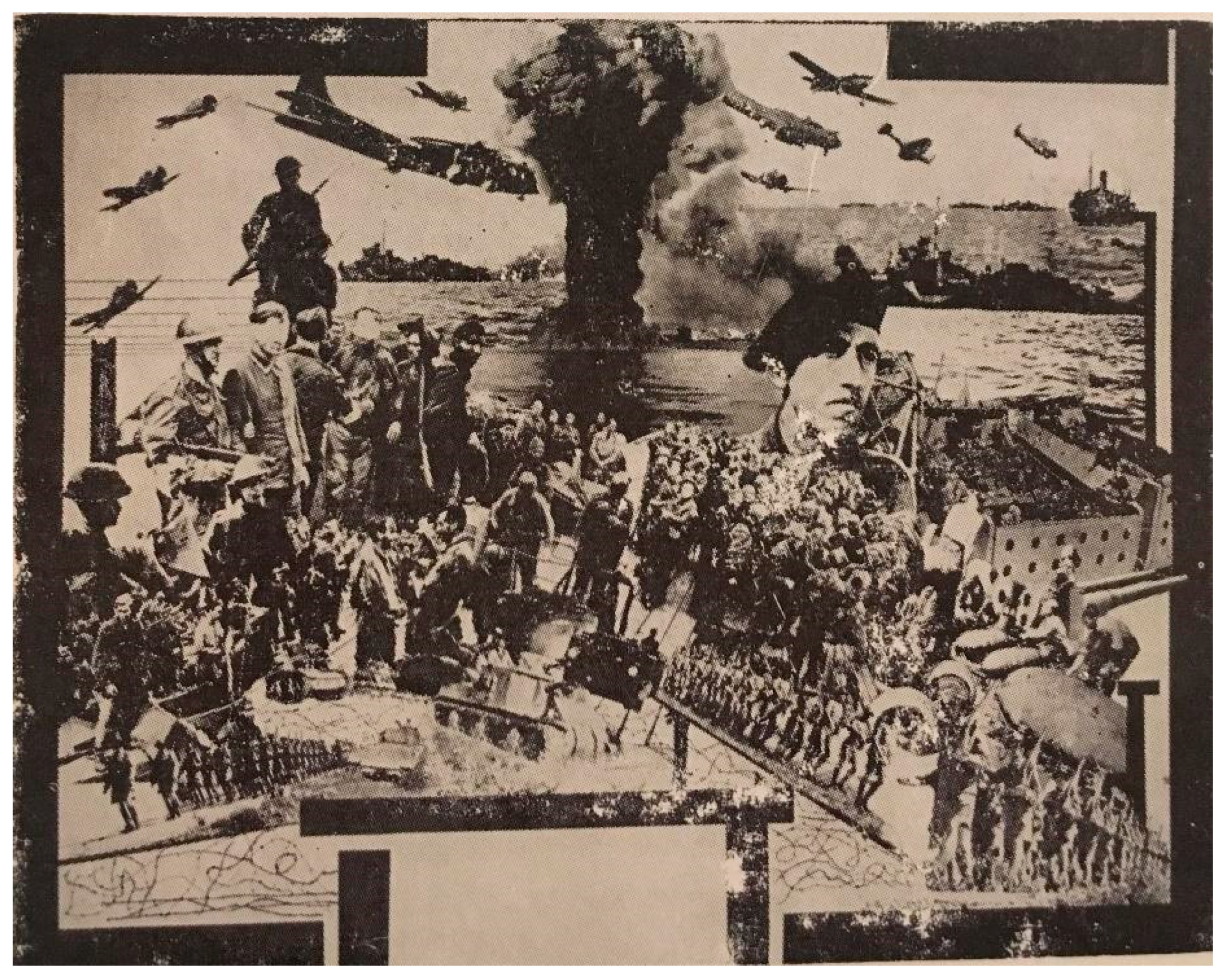

2.2. Disarming the Military Manipulation: Żarnower’s Frieze of Death

Żarnower’s work interferes and comments on the close proximity between interwar Polish graphic design and military imagery. The relationship between illustration design and war was ubiquitous in the Polish interwar period, as seen in the remarkable “military spirit” of the mainstream press, which provided daily commentary on Poland’s international situation after “the country’s borders were hacked out by force of arms after the First World War” (Rypson 2011, p. 344). Military iconography depicting the army and national defense was a “staple of current events” and occupied a prominent place in Polish graphic design. Although the image of the army as a political power structure was a central component of visual propaganda in the 1930s that fulfilled demands for an aura of modernity, it culminated in doing “the Polish state a very bad service, recklessly building the myth of a powerful army, capable of providing a rapid victory over an aggressor already preparing for war” (Rypson 2011, p. 346). The beginning of the Second World War saw brutal attacks on Poland from Germany on 1 September 1939 and from the Soviet Union on 17 September 1939 following their secret agreement to the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact of 23 August 1939 regarding the division of Poland between the two countries. It was in this climate of September 1939 that Żarnower continued to pursue her agitational design work, while simultaneously joining the Government of the Polish Republic in Exile in Paris, which was operational from 1939 in the French capital and subsequently relocated to Angers until 1940, followed by London until 1990.Warsaw after Bombardment: Castle SquareWarsaw after Bombardment: Street in the City CenterWarsaw InflamedBuilding of The Worker in Warsaw, Demolished by German shellsGraves of Warsaw Defenders in the Garden of Ujazdowski Hospital(Idzior 2014, pp. 112–13 in Ślizińska and Turowski 2014)

People of Warsaw!We stood up to fight for the freedom of the Capital City and the freedom of Poland with full faith that stopping the invasion at the thresholds of Warsaw would allow us to organize and order the armed forces of the Republic of Poland in the remaining free areas.The heroic defense of Warsaw became a symbol of our loyalty to independence, it became a visible sign for the whole world of our readiness to give every sacrifice that is possible.The bloodshed, the ruins and the ruins of the Capital will always testify to our will and our right to free state life.The three-week defense of Warsaw, full of the generosity and heroism of the People and the Army, unknown to the world, did not bring the expected military results. Warsaw remained an island within a bilaterally flooding stream of foreign troops. All rumors about the coming help turned out to be untrue. At the same time our elementary devices were destroyed, and above all we were deprived of water.We faced the possibility of the total annihilation of the Capital and its people without any hope of expanding our defense.Warsaw has succumbed to violence. We lost this battle. However, the day will come when the triumphant violence will collapse. We lost this battle with honor, and this fact will solidify us in the future, and will definitely burden us with the future world order after the war.Now all we must do is to continue to maintain the internal consistency that allowed the working class to overcome the invasion and today will create a stronger foundation for future victory.Let us master all reflexes of anger and regret. Let us not allow ourselves to be provoked! Let us keep the seriousness and tranquility of such a tragic moment.We call on you Workers and Intelligentsia to do this. The P.P.S. called you to it, which until now has only called for a violent fight. Because to keep our sobriety and calm today also means to build the discipline we will need for the moment that must and will come to have a decisive meaning.

3. Discussion

PHOTOMONTAGE = the most condensed form of poetryPHOTOMONTAGE = PLASTIC-POETRYPHOTOMONTAGE results in the mutual penetration of the most varied phenomena occurring in the universePHOTOMONTAGE—objectivism of formsCINEMA—is a multiplicity of phenomena lasting in timePHOTOMONTAGE—is a simultaneous multiplicity of phenomenaPHOTOMONTAGE—mutual penetration of two and three-dimensionalityPHOTOMONTAGE—widens the range of possible means: allows the utilization of those phenomena which are inaccessible to the human eye, and which can be seized on photosensitive paperPHOTOMONTAGE—the modern epic.

Following a study conducted by scholar Stan Allen, Stierli observed that axonometric projection equally involves both the mobile and placeless spectator:Countering perspectivalism’s determinism with regard to the location of the viewer, both photomontage and axonometric are characterized by their perceptual ambiguity or even indeterminability, and both tend to leave the viewer in the dark as to his or her own concrete position in space. The deceptive stability of representation in perspective is questioned and destabilized, confronting the perceptual apparatus with an irresolvable visual challenge.

The interaction of the spectator and the specific and intentional placement of constructivist objects are named by Buchloh as two of the main facets of faktura. Through the photomontages in The Defense of Warsaw’s construction and built-in visual narrative sequence, Żarnower placed importance on engaged perception with the intention of spurring political action, while also keeping the process of representation incorporated in the visual messages of the war photographs. The process enabled these images to lead to “purely indexical signs” (Buchloh 1984, p. 90), so as to embed traces into the viewer’s memory. Through different perspectives in Żarnower’s photomontages—simultaneously dynamic and static—the spectator was given the necessary three-dimensional space to penetrate the fragmentary ruins and immediate history of the then still-ongoing World War II. As author of the documents and works, Żarnower urged a reaction via remembrance and memory.If perspective, dependent on a fixed point of view, seemed to freeze time and motion, the atypical space of axonometric suggested a continuous space in which elements are in constant motion. The same property that made axonometric such a useful tool in explaining the construction of complex machinery or spaces … could be exploited here to suggest the simultaneity of space and time. The reversibility of the spatial field allowed for the simultaneous presentation of multiple views. … Axonometric and technical drawings lend themselves to the manipulation of views in an effort to describe the totality of the object.

4. Materials and Methods

Photomontage led me to photography.Aleksander Rodchenko, Reconstruction of an Artist, 1935

During her exile which began in 1937 and became ever more stringent from 1939 onwards, Żarnower started her collection of photographic images. In her diary entry on 16 January 1941, Żarnower wrote:Photography has broken free from being secondary and imitating the techniques of etching, painting or carpet making. Having found its own way it is blossoming and fresh breezes bring a scent that is particular only to photography. New possibilities lie ahead. The multitude of its aspects are as complex as fine drawing, more interesting than photomontage. (…) Then follows the creation of non-existent photographic moments by means of montage. A negative instead of a positive creates a completely new perception. To say nothing of the printing of one picture into another (what is called an “influx” in the cinema), optical distortions, photograms, shots of reflections and so on.Text written by Alexander Rodchenko on October 31, 1934 for the magazine Sovietskoye foto. First published in 1971.

Due to the German occupation beginning on 22 June 1940, Żarnower fled from France, traversing Spain and into Portugal via the cities of Angers and Lourdes with Franciszka Themerson, which she later recounts in a letter to a friend: “I have tender memories of our spirit stove, our stay in Angers and your sad eyes which went on to haunt me in Lisbon …”.5 In 1941, she left Lisbon for New York however, upon arrival was denied permission to enter the country, due to the stringent American immigration policies of the time (Affron and Barron 1997, p. 225). Żarnower was forced to stay in Montreal for seventeen months while she negotiated her entry to the United States, which was finally achieved on 11 June 1943 where she settled in New York City. This period was a time of exile, as described by Edward Said:Called upon by the Department of Propaganda of the Polish Government in Exile [Committee of the Council of Ministers for Information, Documentation, and Propaganda], I completed a number of propaganda posters that were also to appear in America as posters and picture postcards. I have recorded the War in Poland and the tragedy of the Polish nation caused by the occupants’ violence in a number of photo-montages. I have also illustrated a book on ruined Warsaw that would have been published were it not for the downfall of France.

… exile, unlike nationalism, is fundamentally a discontinuous state of being. Exiles are cut off from their roots, their land, their past. They generally do not have armies or states, although they are often in search of them. Exiles feel, therefore, an urgent need to reconstitute their broken lives, usually by choosing to see themselves as part of the triumphant ideology or a restored people.

In the very last chapter of her book Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag refers to the snapshot of a little boy in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943 which was used as a memento mori symbol and seen as a secular icon; raising the question of the appropriate place for displaying such photographs, which she describes as emblems of suffering. She perceives a difference in the reception of photographs depicting concentration camps, when shown in art galleries versus “printed on rough newsprint”. She points out that museums provide distractions for such “solemn or heartrending subject matter” with regards to its reception and argues that due to “the weight and seriousness of such photographs [they] survive better in a book, where one can look privately, linger over the pictures, without talking” (Sontag 2003, pp. 119–21).Cameras began duplicating the world at that moment when the human landscape started to undergo a vertiginous rate of change: while an untold number of forms of biologic and social life are being destroyed in a brief span of time, a device is available to record what is disappearing. (…) A photograph that brings news of some unsuspected zone of misery cannot make a dent in public opinion unless there is an appropriate context of feeling and attitude. (…) Photographs cannot create a moral position, but they can reinforce one—and can help build a nascent one. (…) Photographs may be more memorable than moving images, because they are a neat slice of time, not a flow.

What the photographs by their sheer accumulation attempt to banish is the recollection of death, which is part and parcel of every memory image. In the illustrated magazines the world has become a photographable present and the photographed present entirely eternalized. Seemingly ripped from the clutch of death, in reality it has succumbed [to] it.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Affron, Matthew, and Stephanie Barron. 1997. Exiles + Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler. New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Stan. 2009. Practice: Architecture, Technique + Representation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnost, Adrian. 2016. Teresa Żarnower: Bodies and Buildings. Woman’s Art Journal 37: 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Badger, Gerry. 2014. The Genius of Photography: How Photography Has Changed Our Lives. London: Quadrille. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowicz, Zofia. 1975. Polska Awangarda Artystyczna 1918–1939. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, Mieczysław. 1965. Teresa Żarnowerówna kontynuatorem dzieła Mieczysława Szczuki [Teresa Żarnowerówna as a continuator of Mieczysław Szczuka’s work]. In Mieczysław Szczuka. Edited by Anatol Stern and Mieczysław Berman. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, Yve-Alain. 1990. Painting as Model. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchloh, Benjamin. 1984. From Faktura to Factography. October 30: 82–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchloh, Benjamin. 1999. Gerhard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive. October 88: 117–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekalski, Stanisław. 2000. Avant-Garde and the Myth of Rationalization: Polish Photomontage 1918–1939. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskiego Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Giżycki, Marcin. 1996. Awangarda Wobec Kina: Film w Kręgu Polskiej Awangardy Artystycznej Dwudziestolecia Międzywojennego. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Małe. [Google Scholar]

- Grabska, Elżbieta. 1982. The Years 1914–1918 and 1939–1949. The Problems of Periodisation of the Inter-War Period. In Art in the Inter-War Period. Warsaw: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Gurianova, Nina. 2012. The Aesthetics of Anarchy. Art and Ideology in the Early Russian Avant-Garde. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworowska, Janina. 1976. Polska Sztuka Walcząca 1939–1945 [Polish Fighting Art 1939–1945]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe. [Google Scholar]

- Józefacka, Anna. 2011. Rebuilding Warsaw: Conflicting Visions of a Capital City, 1916–1956. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kracauer, Siegfried. 1927. “Die Photographie” Frankfurter Zeitung. Reprinted in Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament. Edited and Translated by Thomas Levin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Król, Monika. 2002. Collaboration and Compromise: Women Artists in Polish-German Avant-Garde Circles, 1910–1930. In Central European Avant-Gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930. Edited by Timothy O. Benson. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, Bożena. 1966. U Źródeł Grafiki Funkcjonalnej w Polsce. In Ze Studiów nad Genezą Plastyki Nowoczesnej w Polsce. Edited by J. Starzyński. Wrocław: Ossolineum. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Jerzy. 1987. Grupa Jung Idysz i żYdowskie Środowisko Nowej Sztuki w Polsce, 1918–1923 (The Young Yiddish Group and the Jewish Context for New Art in Poland, 1918–1923). Warsaw: Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach, S. A. 1999. Modern Art in Eastern Europe: From the Baltic to the Balkans, ca. 1890–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, Victor. 1997. The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy 1917–1946. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mertins, Detlef. 2001. Architectures of Becoming: Mies van der Rohe and the Avan-Garde. In Mies in Berlin. Edited by Terence Riley and Barry Bergdoll. New York: Muzeum of Modern Art, pp. 106–33. [Google Scholar]

- Morawińska, Agnieszka. 1991. Artystki Polskie: Katalog Wystawy. Warsaw: National Museum in Warsaw. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz. 1998. Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Poprzęcka, Maria. 2014. Foreword: Non-Memory. RIHA Journal 2014 (Special Issue Contemporary Art and Memory). : 0104. [Google Scholar]

- Rypson, Piotr. 2011. Against All Odds. Polish Graphic Design 1919–1949. Krakau: Karakter. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 2000. Reflections on Exile and Other Literary and Cultural Essays. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ślizińska, Milada, and Andrzej Turowski. 2014. Teresa Żarnower (1897–1949). An Artist of the End of Utopia. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 2008. On Photography. London: Penguin Modern Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Stierli, Martino. 2018. Montage and the Metropolis. Architecture, Modernity, and the Representation of Space. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Struk, Janina. 2004. Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Sarah. 2004. Deborah Wye. In Artists and Prints: Masterworks from The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Traba, Robert. 2013. Traba, Robert. Konieczność zapominania, czyli jak sobie radzić z ars oblivionis [The need to forget, that is how to deal with ars oblivionis. Herito 13: 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Turowski, Andrzej. 1981. Konstruktywizm Polski. Próba Rekonstrukcji Nurtu (1921–1934). Wrocław: Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Turowski, Andrzej. 2000. Budowniczowie Świata: z Dziejów Radykalnego Modernizmu w Sztuce Polskiej [Builders of the World. The History of Radical Modernism in Polish Art]. Kraków: Universitas. [Google Scholar]

- Vattano, Starlight. 2018. Graphics Analysis of the Projekt Kina by Teresa Żarnowrówna, 1926. In Women’s Creativity since the Modern Movement (1918–2018). Toward a New Perception and Reception. Edited by Helena Seražin, Emilia Maria Garda and Caterina Franchini. Ljubljana: France Stele Institute of Art History. [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky, Matthew, and Peter Demetz. 2007. Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918–1945. Washington: National Gallery of Art in association with Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Żarnowerówna, Teresa. 1923. Constructivism in Poland 1923–1936. Catalogue of the Exhibition of New Art. Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard Gallery, pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2000. Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory Through the Camera’s Eye. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zerubavel, Eviatar. 1997. Social Mindscapes: An Invitation to Cognitive Sociology. Cambridge: Havard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2004. The social marking of the past: Toward a socio-semiotics of memory. In Matters of Culture. Cultural Sociology in Practice. Edited by Roger Friedland and John Mohr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 184–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, Joshua D. 2003. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The authors of the publication: scholars Milada Ślizińska and Andrzej Turowski give an explanation, to be found on the very first pages, outlining the reasons for keeping the artist’s maiden surname in the title with the ending-ówna. First of the introduced reasons is that the artist was not married and that such form of a miss was popular in the environment of the Polish intelligentsia in the inter-war period. In addition, in the artistic circles it was a form of an emancipation, as well as with regard to women with Jewish background, it underlined the declaration of affiliation with Polish culture. As in this paper I am taking the period of “An End of Utopia”, I will consciously stick to the ‘Żarnower’ version of artist’s surname, as since her definite departure from Poland to Paris in 1937—and later to the United States—the artist presented herself as Zarnower or Zarnover, as it can be tracked throughout her numerous résumés written in the war period. |

| 2 | The museum was founded in 1930, concurrent to other early modernist institutional projects such as El Lissitzky’s Cabinet of Abstraction commissioned in 1927 for the Hannover Provincial Museum in Hanover Germany and the founding of the Museum of Modern Art in 1929 in New York, United States. |

| 3 | Press Release, Storm Women. Women Artists of the Avant-garde in Berlin 1910–1932, at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 12 October 2015: https://www.schirn.de/en/magazine/context/storm_women_women_artists_of_the_avant_garde_in_berlin_19101932/. |

| 4 | United States Holocaust Memorial Museum # 31324, Julien’s Bryan’s gift, no. 8 of 19, In: Teresa Żarnower (1897–1949). An Artist of the End of Utopia, eds. Ślizińska, Milada and Andrzej Turowski, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, 2014, 117. |

| 5 | Teresa Żarnower in: Teresa Żarnower (1897–1949). An Artist of the End of Utopia, eds. Ślizińska, Milada and Andrzej Turowski, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, 2014, p. 167. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogucka, M.A. Teresa Żarnower’s Mnemonic Desire for Defense of Warsaw: De-Montaging Photography. Arts 2020, 9, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030084

Rogucka MA. Teresa Żarnower’s Mnemonic Desire for Defense of Warsaw: De-Montaging Photography. Arts. 2020; 9(3):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030084

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogucka, Maria Anna. 2020. "Teresa Żarnower’s Mnemonic Desire for Defense of Warsaw: De-Montaging Photography" Arts 9, no. 3: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030084

APA StyleRogucka, M. A. (2020). Teresa Żarnower’s Mnemonic Desire for Defense of Warsaw: De-Montaging Photography. Arts, 9(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030084