Abstract

Creative holography could still be considered a fringe medium or methodology, compared to mainstream art activities. Unsurprisingly, work using this technology continues to be shown together with other holographic works. This paper examines the merits of exhibiting such works alongside other media. It also explores how this can contribute to the development of a personal critical framework and a broader analytical discourse about creative holography. The perceived limitations of showing holograms in a “gallery ghetto” are explored using early critical art reviews about these group exhibitions. An international exhibition, which toured the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia, is used as a framework to expand the discussion. These exhibitions include examples of the author’s holographic work and those of artists working with other (non-holographic) media and approaches. The touring exhibition as a transient, research-informed process is investigated, as is its impact on the critical development of work using holography as a valid medium, approach, and methodology in the creative arts.

1. Introduction

It is not unusual for works produced in similar media, or those which investigate similar processes, to be visually and critically grouped. It was, for decades, an essential curatorial backbone for exhibitions. This can encompass broad areas of investigation, such as painting, sculpture, video, print, or performance, and provides a loose, comparative grouping for audience consideration.

Within those primary media areas, there are extensive practical, theoretical, critical, and cultural subsections, which then become more engaging as they start to highlight, or juxtapose, works which activate discussion or respond to a curatorial “thesis”. From this develops the construct of the gallery as a “laboratory” or research “workshop” (Hou et al. 2013), which can be most recently seen in the range of activities at the Research Pavilion organized by UniArts (University of Helsinki) alongside the Venice Biennale in 2019 (Research Pavilion 2019).

2. Safety in Numbers

Unsurprisingly, works with holography were grouped since the mid-1960s (Leith and Upatnieks 1965), when this technology developed sufficiently to allow public displays. The “blockbuster” exhibitions of the 1970s and 1980s testified to the enthusiasm of the public for these wondrous, and often “magical”, gatherings (Johnston 2016). They also attracted ridicule, and sometimes venomous comments, from art critics who, quite rightly, questioned where the critical or creative content was. They were concerned about the lack of any aesthetics beyond the spectacular, high-fidelity, display of seemingly three-dimensional objects. When the group exhibition “Holography ‘75: The First Decade” was held at the relatively new International Center of Photography (ICP), New York, it was met with harsh criticism from art critic Hilton Kramer in a review for the New York Times. His review became significant for artists working with holography, as well as for critical observers (Kramer 1975).

For the group of artists taking part in the exhibition and the curators who organized it, it was a significant attack, particularly as this was an early occasion when a curated group exhibition took place in a legitimate cultural venue. Other exhibitions of holography, showing work by individual artists, took place previously, in notable art venues, but this was an early attempt at surveying the field by gathering together a wide range of work and makers. The technical, commercial, and scientific examples included in the exhibition were compared to early pieces made by artists and triggered some of the criticism from Kramer.

Kramer commented that the exhibition “… dramatically underscores the center’s refusal to confront the difficult aesthetic problems that a museum specializing in photography is now obliged to deal with. An aesthetic void is always vulnerable to the romance of technology, and this is all that the present exhibition offers” (Kramer 1975).

While these comments ostensibly expressed Kramer’s concern for the stance of the venue and its approach to separating photography from other cultural genres, they also allowed him to refer to a colleague’s previous scathing review as a way of confirming his opinion that little changed. “… ‘Holography ‘75’ is being offered to us as nothing less than ‘an event of historic importance’. It even claims to be the ‘first’ show of its kind—which is unkind to the ‘N Dimensional Show’ of holography that the Finch College Museum of Art mounted several years ago. Reviewing that exhibition, my colleague Grace Glueck wrote that it had ‘all the aesthetic kick of a postcard from Montauk’, and ‘Holography ‘75’ certainly marks no discernible esthetic advance.” Kramer carefully selected one of the negative statements from Glueck’s review; however, she did attempt to offer an insight into the approach taken by the artists included in the exhibition—it was not all acerbic rhetoric (Glueck 1970).

3. Curator’s Response

Rosemary (Posy) Jackson, who curated the ICP exhibition with Jody Burns, commented that “Hilton Kramer was simply doing what was expected of him as the establishment figure in art criticism and that, by damning holography, as he did, he was utterly in line, historically, with what the critics in Paris were saying about the first photography exhibition” (Jackson 2019).

As Jackson points out, however, Kramer’s criticisms were based on misguided expectations. “… The unfortunate issue was that neither Jody, nor I, nor Cornell (Cornell Capa, Director of the ICP) ever said Holography ‘75 was an art exhibition. It was simply referred to as ‘a new medium’. But Hilton Kramer took it upon himself to critique the works on display as if we felt they were all fine art. That was his mistake, not ours. But his disparaging comments hung around what was soon to be some really good art holography for far too long” (Jackson 2019).

Jackson concludes by saying, “Those who needed someone else to tell them what they were seeing have always been too insecure to make their own minds up. So, a lot of really good work gets passed by and that is a grievous shame. […] A lot of what Mr. Kramer said was dead on right. Fortunately for holography, and for the brave artists who took it on, his opinion did not make much difference (to them). Unfortunately, it did mark holography for way too long as a wannabe, pariah, kitschy tool. But, in reality, that is more the fault of how the art buyers kowtow to the critics than whether Mr. Kramer’s comments were valid or true or important. The real situation is that holography as an art medium was then, and maybe still is, light years ahead of everybody in the visual arts” (Jackson 2019).

4. The “Aesthetic Naiveté”

So how could the curators and organizers have got it so wrong for Kramer? These large group shows were surveys of the “state” of the process, technology, and medium and, as such, may not, at the time, have captured an identifiable creative development which went beyond the technological progress. Either that or the emerging engagement and investigation by artists was diluted due to the bombastic demonstrations of advanced technology by the scientific, technical, and commercial examples. For the public, the story was very different. In a definite age of technological advance and associated hope for a better future, they were willing to wait in line to see the spectacle—one which was not presented with such mystery, probably since Brunelleschi demonstrated perspective or Giotto unveiled his work in the Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel.

Kramer twisted the knife further: “The aesthetic naiveté of this show must really be seen to be believed. No mere description could begin to do it justice. Images of a stupefying innocuousness, ranging from peep-show porn and low-grade beer commercials to the even more ludicrous parodies of so-called ‘serious’ art, are unrelieved by the slightest trace of aesthetic intelligence” (Kramer 1975). Perhaps the show made itself vulnerable to such an attack due to the wide range of examples, which included commercial work and pieces by artists beginning to adopt the process, as it became problematic to differentiate between them. “It is difficult to know which is the more repugnant: the abysmal level of taste or the awful air of solemnity that supports it” (Kramer 1975). What works in commerce is not always a critical accelerant for explorations by artists. Kramer continues, “There are, to be sure, a few ‘artistic’ attempts here at abstraction and pop art and the familiar neo-dada repertory, but these are even more laughable than the outright examples of kitsch. Much of the work in this show has, I gather, been produced not by ‘artists’ but by physicists professionally involved in holographic technology. The physicists appear to favor objects out of the local gift shop, whereas the ‘artists’ do their shopping in provincial art galleries…” (Kramer 1975).

When this exhibition took place, a curated painting exhibition, for example, would have been unlikely to include works by artists shown alongside industrial and chemical examples of what the pigment could achieve. Paint as a creative medium has an established pedigree, an accessible critical history. Holography was (and continues to be) such an unusual visual process that it seemed justifiable, in a survey show, to include examples of that uncommon view, manifest through research, commerce, and art. Currently, as the gallery spaces become a manifestation of the research studio and comfortably act as a reactive and generative venue, such a curatorial stance would be accepted and, in many cases, applauded. Too much, too early, perhaps?

5. Out of the Gallery Ghetto

As part of the critical investigation and development of my practice as an artist, I participated in institutional research critiques where my work with holography and the work of my colleagues (in a variety of media) were placed under critical pressure and analysis. These activities take place as part of the fine art course on which I teach. We move out of the institution, physically away from the demands of the courses we teach, to mirror the activities of our students and place our work under open, collegial pressure. In one of these sessions, I presented details of my work, which was on show in Korea, as part of a group exhibition curated by Professor Juyong Lee, which included selected holograms by 13 international artists. I was advised not to show work in holography exhibitions, but to investigate opportunities to exhibit alongside artists working in other media, so that my activities could be evaluated beyond the narrow focus of holography. That advice and its critical context were valid. Works in a specific medium should not support themselves (or dodge critical examination) by subtle isolation or through a process of “safety in numbers”. This aspect of the gallery ghetto (Pepper 1994) is an issue I am curious about, almost since my first engagement with the holographic process.

Early works by artists using new processes, methodologies, or technologies can be critically reviewed and assessed by bringing together examples using the same medium. A survey exhibition of the use of digital imaging, or early analog video, for example, is quite acceptable. The difference here is that a historical and critical framework exists, which can be used for evaluation. Currently, holography appears to lack that framework. There were comparatively few attempts to provide considered critical observations.

Aside from the blockbuster survey holography shows, holographic works are included alongside other media, away from the gallery ghetto, and framed within the critical sensitivities of municipal, state, and commercial galleries. The exhibiting artists can be divided into two distinct groups:

- Artists engaging primarily with holography, who developed a visual, critical, and practical vocabulary over several years. In this case, holography would be considered their practice.

- Artists significantly established in other media, who experimented with the holographic process, often supported by technicians, manufacturers, or scientific labs.

The former are more likely to exhibit alongside other artists using holography, which can be seen as a positive process of peer analysis or comparative critical scrutiny. Occasionally, examples of their work are shown in exhibitions with a curatorial stance, alongside similar ideas or approaches which use a variety of non-holographic media or techniques.

The latter present their holographic works as a part of group or solo exhibitions. These are generally selected because of a specific investigation or approach, which connects with other works on display. Examples include Bruce Nauman, who experimented with holography alongside print, neon, paint, video, and audio; Chuck Close, best known for his large-scale painted portraits, who experimented with holography to produce five holographic portraits; and James Turrell, whose work with light led to the use of holography as a way of testing his visual vocabulary. Each of these established artists connects to an extensive critical framework about their work, which can be referenced. It is, therefore, possible to examine why they experimented with holography and how this contributed to their practice. Their works are investigations, made prominent by holography, not, as in the most negative connotations, holograms which mainly demonstrate the visual impact of the medium. It is these “holograms for hologram’s sake” which attracted the irritation of Kramer and Glueck.

6. The Exhibition as a Space for Critical Reflection

I, like many of my colleagues working mostly with holography, exhibited in gallery ghettos and un-curated exhibitions which included only holograms. They offer a location for peer comparison and a space to contextualize our activities within a professional field. In this instance, they are useful as a learning opportunity and platform for self-reflection. Work I admire from engaged artists, who use holography as an integral element in their practice, provides an opportunity for discussions around approaches, intention, and staging. They are invariably not a location for critical discussion, being mainly self-referential and self-congratulatory. It is for this reason that I completely understand the advice from my fine art teaching colleagues referred to in Section 5.

A group exhibition, Art in Holography: Light, Space, and Time (Bjelkhagen and Pombo 2018) at the Aveiro City Museum, Portugal, as part of the 11th International Symposium on Display Holography, separated itself from previous exhibitions by establishing a clear demarcation between scientific examples and works by artists. Previously, as is the case in many international, subject-specific conferences in general and holography in particular, work from delegates would be exhibited together in a “bring and show” format with little consideration for staging, grouping, curatorial stance, or contextualization. Whatever arrived with the delegates was put on show. This type of exhibition has its place in a meeting of experts, by offering an opportunity to contrast, compare, and swap technical or procedural information. However, such a model would be difficult to justify in an international art conference. There would inevitably be a curated exhibition or pre-announced platform for research and exchange.

The significant difference of the Aveiro exhibition was that it took place in a respected cultural museum which implied a credibility not typically associated with a conference “trade show”. It is implied, rather than real, because the work appears in a venue with a cultural and curatorial pedigree and has a subtle influence on a viewer’s perception of what is shown there. This does not undermine the value of alternative or fringe exhibition spaces, or the questions surrounding institutional perceptions of art and culture.

The Aveiro exhibition also followed a familiar exhibition framework, with a printed catalog, contextualizing the work on show through the activities and achievements of the 25 artists included. It had an extended viewing period (unlike trade shows which tend to finish when their conferences finish), and it was open, free of charge, to the public. One aspect of specialized conferences and subject-specific exhibitions connected to them is that they are only accessible to the expert audience attending the conference. Experts are talking to experts—a closed-loop lacking in external provocation.

7. Silence Is Golden

One positive aspect of the Aveiro museum exhibition was that active critical discussion did take place. This is not unusual in institutional exhibitions, where public discussions are actively organized and promoted. However, it is unusual in exhibitions containing mainly holograms. During a research activity organized by artist Pearl John (one of the Aveiro exhibition organizers), she invited other exhibiting artists to critically interrogate her work in Holography: Light, Space, and Time. Organized as part of her doctoral research, it used a robust pedagogic approach tested in contemporary fine art degree teaching—the “show and listen” seminar (or silent student critique) (Elkin 2012), in which the presenting artist (student) is not allowed to explain or discuss their work, but is asked to remain silent and listen to the discussions of a critical audience. This was the first time I encountered the use of this critical feedback assessment technique applied to holography in a public exhibition. John obtained a significant amount of relevant and critical feedback, which contributed to her PhD thesis (John 2018).

As part of an undergraduate and postgraduate fine art teaching team, I used this technique for several years to enhance the teaching and development of critical engagement within contemporary art. It facilitates the early development of a critical voice.

If work on show needs to be explained, then it is probably not functioning in the manner the artist hoped. The separation between “intention” and “interpretation” is too wide. If the meaning, context, or background of a work is introduced before a discussion, it limits the interpretation, as viewers will be unable to provide subjective analysis or feedback about the difference between what they see and what they are “told” to see.

An additional technique, often used in our fine art group seminars, is to restrict the discussion from the viewing audience to a series of observational questions. This is particularly valuable in early-stage critical discussion, where a student may be uncomfortable about using a critical voice, or unfamiliar with critical vocabulary.

Questions might include the following, among others:

“I am confused because the image I am looking at is not visible when I move over here. Is this intentional?”

“Was that the intention of the artist or a limit of the medium being used?”

“Am I expected to understand the relationship between the part of the image in front of the work and the ones behind it?”

“Does this really need to be a hologram—could it have worked just as well as a sculpture?”

“Why is the frame so reflective—was it the intention of the artist to distract me from looking at the image?”

Even the most basic or spontaneous observations framed in this manner open up a wide range of significant critical enquiries, which can be evaluated and considered by the artist/maker.

8. Alternative Documents

Holography deals extensively (consciously and by implication) with the ephemeral image, the “not quite there”, the “transient and momentary event”, and the “peripheral view” (Pepper 2018). Acknowledging these significant attributes, work using holography was included in an international exhibition staged in conjunction with the Alternative Document conference, of the same name, held at the University of Lincoln, United Kingdom (UK), in 2016 (Figure 1). The conference call for participation solicited work which engaged with a wide range of media and approaches, including fine art, live art, performance theory, translation studies, art history, theatre studies, cultural studies, curation, conservation, architecture, and archival studies. If holography was included, it would be because of its engagement with the conference and exhibition curatorial view and not because it was “quite clever” at recording the world around us. There was a declared interest in aspects of the “fleeting event”. In the call for participation, curator, artist, and academic Dr. Angela Bartram wrote, “Beyond most ephemeral artwork, a memory remains in the mind of the observer, and this forms part of the legacy of the fleeting event. However, memory is mostly a personal experience, that shifts, mutates, and fades over time to become distant, different to its origin, and in this way its archival potential is unreliable. To overcome this dilemma, a variety of lens-based archival methods have become the tradition of recording the ‘actual’ event in as far as it is possible” (Bartram 2016).

Figure 1.

Announcement for the Alternative Document conference and exhibition, Lincoln Performing Arts Center, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, United Kingdom (UK), 2015. Image used by permission of the symposium organizer.

Holography is often cited as an archival process, with the ability to record and replay incredibly high-fidelity records of three-dimensional objects (Schinella 1973). Therefore, its inclusion as part of this conference and exhibition appears appropriate. What is unusual here is for holography to be treated as an aspect of an artist’s practice and critical investigation, rather than as a spectacular or optical recording oddity.

Following the conference and exhibition in 2016, a series of subsequent exhibitions took place, entitled Documents Alternatives (2016–2018). These toured three further arts venues: Airspace Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, UK; Verge Gallery, University of Sydney, New South Wales (NSW), Australia; and BSAD Gallery, Bath School of Art and Design, Bath, UK.

The result was a transient series of critical observations, manifest differently at each location. Work and artists changed, yet the curatorial stance of the exhibition remained stable. Bartram engineered a framework which encouraged the development of work within and between venues. It valued and stimulated reflective analysis of the work at each gallery and referred back to the original call for participation: “… Recordings are mediated and translated for posterity through the direction of the person holding the device and document their viewpoint and subjective encounter with the work. This creates an archival document open to subjective discussion, as a memorial and work in its own right, and of which alternatives are often sought” (Bartram 2016). Here the “archival document” developed and shifted in response to each exhibition space and the newly developed works around it. It became responsive within the touring exhibition framework. Again, this is unusual for the medium of holography, which so often presents brief moments of development unrelated to other works around it. This lack of critical “response” may well have been a contributing factor to the less than favorable opinions of critics Kramer and Glueck, referenced in Section 2.

9. Testing in and between the Gallery

My contributions to the Documents Alternatives series benefitted significantly from the critical framework in which they were shown, the pressure placed upon each work through the surrounding discussions, which underpinned the associated conference, and the approaches of other artists selected to take part, including Bartram O’Neill, Tim Etchells, David Brazier and Kelda Free, Hector Canonge, Rachel Cherry, Luce Choules, Emma Cocker and Clare Thornton, Kate Corder, Chris Green and Katheryn Owen, Louise K Wilson, Jordan McKenzie, and Rochelle Haley.

The results over three years were four progressive manifestations and approaches to the same enquiry. In my case, these included an initial sculptural installation (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4), an edited version, which responded to the volume of the surrounding exhibition space (Figure 5 and Figure 6), photographic representations of the holographic elements within the work (Figure 7 and Figure 8), and illuminated “relics” of the initial installation (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The fifth, and possibly final, manifestation, to be presented in the autumn of 2019, will be an entirely digital, online work. There will be no visible hologram, no artefacts, and no physical debris, only the transient memory and the historical archive of past presentations.

Figure 2.

The Alternative Document exhibition, Project Space Plus, University of Lincoln, UK. Three Nine—2016 (columns at the rear of the gallery). Installation including digital reflection hologram and three gallery plinths supporting Kodak Carousel 35-mm projectors. Created by author.

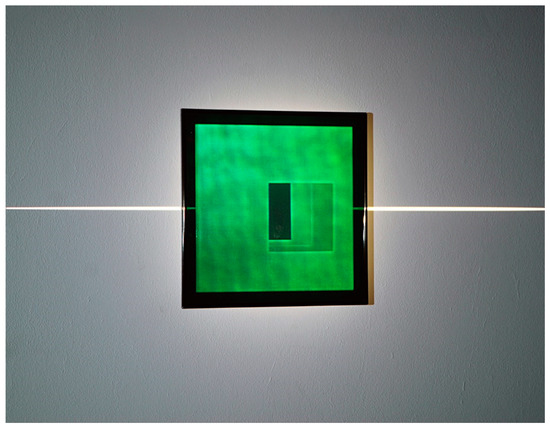

Figure 3.

Detail: testing of digital hologram illuminated by one of the three 35-mm slide projectors. Part of an investigation undertaken at Nottingham Trent University’s Fine Art Summer Lodge. Created by author.

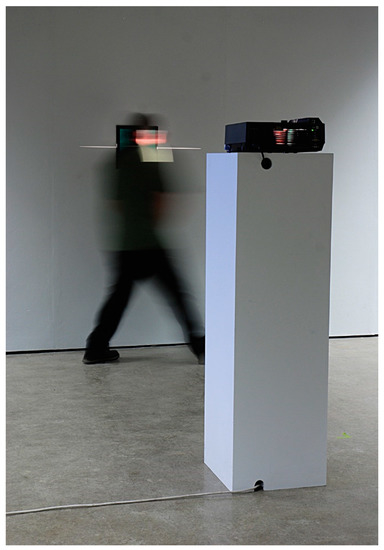

Figure 4.

Testing of the interference caused when viewing the hologram and the act of interrupting the projected light used to reconstruct the holographic image. Part of an investigation undertaken at Nottingham Trent University’s Fine Art Summer Lodge. Created by author.

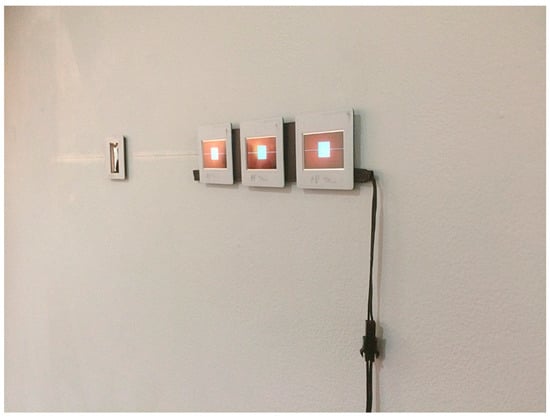

Figure 5.

Installation of digital reflection hologram and single 35-mm slide projector adapting to the vertical orientation of the Airspace gallery wall. Created by author.

Figure 6.

Detail: The bottom edge of the digital reflection hologram and its intersection with the projected “drawn” line from the 35-mm slide projector.

Figure 7.

Gallery installation view of Three-Nine 35 mm alongside Tim Etchells, Red Sky at Night. Image credit: Document Photography and Verge Gallery. Used by permission.

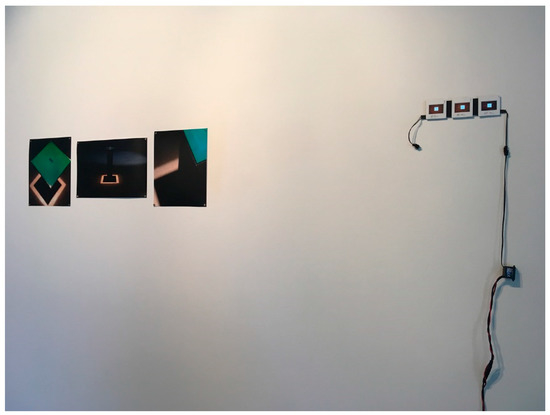

Figure 8.

Detail: Three 35-mm slides mounted on electro-luminescent panel with three digital color photographs of the installed hologram. Slides originally used to project light onto Work 1. Image credit: Angela Bartram. Used by permission.

Figure 9.

Three-Nine 35 mm Drawn has an additional slide included, as well as hand-drawn pencil lines on the gallery wall. Created by author.

Figure 10.

Detail: Three-Nine 35 mm Drawn showing the additional unprojected and unilluminated slide, as well as the hand-drawn pencil line on the gallery wall. Created by author.

The current four variants of the work outline a prolonged investigation and are “judged” alongside those of the other participating artists at each venue. This extended and intensive “gallery as research” opportunity allows a physical, theoretical, and critical development through adjustments, remaking, and restaging. Within this framework, it is possible to demonstrate the use of holography as an integral contribution to an artist’s developing practice, rather than an unusual manifestation included in an exhibition for visual appeal, unconnected to a curatorial proposition.

10. Progressive Development

What follows are illustrations of each of the four progressive works which make up the Documents Alternatives series to date and take the form of reflective, momentary conclusions—a visual and critical “litmus test”, prompted by the exhibition framework which surrounded them.

Work 1: The Alternative Document, Project Space Plus, Three Nine—2016

Three gallery-quality plinths stand parallel to the display wall and support three Kodak Carousel 35-mm slide projectors. Each contains a single slide of a rectangle of light bisected by a thin horizontal line. These images are projected across the short distance between the plinths and the wall. Each of the horizontal lines touch, producing a much larger “horizon” made up of the projected image from three distinct parts of the gallery. This is not a single line but appears to be so.

The center projection is occupied by a digital reflection hologram on the gallery wall, made up of three parallel planes of light, each with a rectangle “cut” out of the center. These planes appear to be “stacked” in front of each other, allowing the viewer to look through the “holes” in each, to the plane located behind. One plane is located behind the holographic plate, the second appears on the plate (the traditional picture plane), and the third appears in front of the hologram between the viewer and the holographic plate. They conform to a model of holographic space outlined in 1989 (Pepper 1989).

Produced to be illuminated, with light shining directly onto the hologram, this differs from other types of holographic display that require light shining from above and at an angle of 45–60 degrees (a more “traditional” orientation). This illumination layout allows viewers to intercept the projected light and “get in the way” of the illumination, which then restricts the display of the image.

The act of viewing prohibits the view. The “document” becomes unreadable when there is an attempt to “read” it.

Gallery visitors are free to engage with the installation from behind, giving a view of all three projections (and the central planes displayed in the hologram), as well as walking between the plinths and the gallery wall, where they naturally intercept light from the projectors and “animate” or “distort” the wall-based display.

Work 2: Documents Alternatives #1, Airspace Gallery, Three-Nine—2017

A variant of the original installation (Figure 1), this iteration compresses the configuration to one of the three original projections.

Here, a single 35-mm slide projector illuminates a holographic, wall-based, series of rectangular spaces. Each element in the installation could be considered an object: the plinth supporting its projector, the slide in the projector, the projector itself, and the implied (holographic) spaces visible on, behind, and in front of the gallery wall.

We continually make visual, spatial, and critical assumptions about the objects and materials which populate our surroundings—our documents, our documentation. By attempting to examine the hologram, through closer “looking”, its wall-based visual information dislocates from its presentation. You, as the observer, block the reconstruction of the holographic spaces. You stop yourself from “seeing” and become the “seen”.

Work 3: Documents Alternatives #2, Verge Gallery, Three-Nine 35 mm—2018

Work 4: Documents Alternatives #3, BSAD Gallery, Three-Nine 35 mm Drawn—2018

Documents Alternatives #3 was hosted by the Art Research Center, Bath School of Art and Design, BSAD Gallery, in conjunction with an accompanying symposium, which focused on artistic process and practice. In the case of my contribution, a workshop exploring the unsupported mark and “drawing” in space, through the interception of projected light, referred directly back to work on show in the gallery. In this iteration, the three original 35-mm slides used to illuminate the gallery wall and central hologram in the first installation (Figure 2) are illuminated from the back, using an electro-luminescent panel. These slides were projected for 8 h a day and, during the exhibition period, became denatured, changing color from black to pink, due to the heat of the projectors used to illuminate them. The “pinking” is evident in these back-illuminated slides, anchoring them within an historical framework (the impact of the past on the physical nature of the objects—altered by light). In addition, a fourth, unprojected and unilluminated slide, to the left of the others, is linked by a pencil line drawn directly onto the gallery wall, echoing the original line of light projected across the gallery in the first installation (Figure 1).

11. Conclusions—Achieving the Tipping Point

During its early developmental stages, holography was not exposed to the critical analysis applied to other media and methodologies. This is unsurprising for a visual process which emerged from a scientific and engineering framework and which was quickly identified as a visually spectacular and attractive tool. Emphasis was placed on its novelty, which distracted from its exploration by artists who were attempting to use it within their practice.

More recently, artists and curators developed a confidence allowing them to apply critical analysis to work using holography. The critical questioning which took place in the Aveiro City Museum, as part of a wider PhD research process, and the progressive development of each of the works shown in the Documents Alternatives exhibitions suggest that holography can operate as an integral and considered element within research-informed practice and that there is a willingness on the part of artists and curators to establish a critical platform.

The holography blockbuster exhibitions of the 1970s and 1980s are now valuable historical points of reference, alongside the observations made by the few critics who attempted to examine this emerging medium. Artists continue to work with holography within their practice (albeit very few) and, in doing so, are developing a more identifiable critical basis for their work, which is beginning to attract the same rigor of analysis applied to other media. We appear to have achieved the tipping point.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Nottingham Trent University School of Art and Design and its research team for supporting the writing of this paper, my colleagues in fine art, for providing an environment where practice-lead research is considered a viable pedagogic imperative, and to the galleries and curators who have offered considerable freedom and support to allow me to test out ideas and question issues relevant to my research and practice.

Conflicts of Interest

Andrew Pepper is editor of this special Arts issue and, to maintain academic rigor and editorial quality, this paper has been independently double peer-reviewed and the decision to include it in this issue has been made entirely by the Arts editorial board.

References

- Bartram, Angela. 2016. The Alternative Document. Call for participation. Lincoln: University of Lincoln. [Google Scholar]

- Bjelkhagen, Hans, and Pedro Pombo, eds. 2018. Art in Holography; Light Space & Time, 1st ed. Aveiro: University of Aveiro, ISBN 979-972-789-551-9. [Google Scholar]

- Elkin, James. 2012. Art Critiques: A Guide, 2nd ed. Washington: New Academia, p. 76. ISBN 978-0-9860216-1-9. [Google Scholar]

- Glueck, Grace. 1970. Holograms in Their Infancy. New York Times, Arts. April 25, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Hanru, Natalie King, and Victoria Lynn. 2013. Hou Hanru. Victoria: The University of Melbourne, p. 12. ISBN 978 0 7340 4887 5. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Rosemary (Posy). 2019. Email correspondence with the author. May 9. [Google Scholar]

- John, Pearl. 2018. Temporal and Spatial Coherence: Chronological and Affective Narrative within Holographic and Lenticular Space. Ph.D. Thesis, De Montfort University, Leicester; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Sean. 2016. Holograms: A Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198712763. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Hilton. 1975. Holography—A Technical Stunt. New York Times, Arts and Leisure, Art View, July 20, D1. [Google Scholar]

- Leith, Emmett, and Juris Upatnieks. 1965. Photography by Laser. Scientific American 212: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, Andrew. 1989. Holographic Space: A Generalised Graphic Definition. Leonardo: Journal of the International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology. Holography as an Art Medium 22: 295–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, Andrew. 1994. Beyond the Gallery Ghetto. In The Creative Holography Index. Bergisch Gladbach: Monand Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, Andrew. 2018. I am here—You are there: Let’s meet sometime. Alternative Documents special issue, Studies in Theatre and Performance. Taylor & Francis 38: 251–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Pavilion. 2019. Venice. Available online: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/474888/474889 (accessed on 6 June 2019).

- Schinella, Robert. 1973. Holography: The Ultimate Visual. Optical Spectra 7: 27–34. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).