Synagogue Architecture of Latvia between Archeology and Eschatology

Abstract

1. Introduction

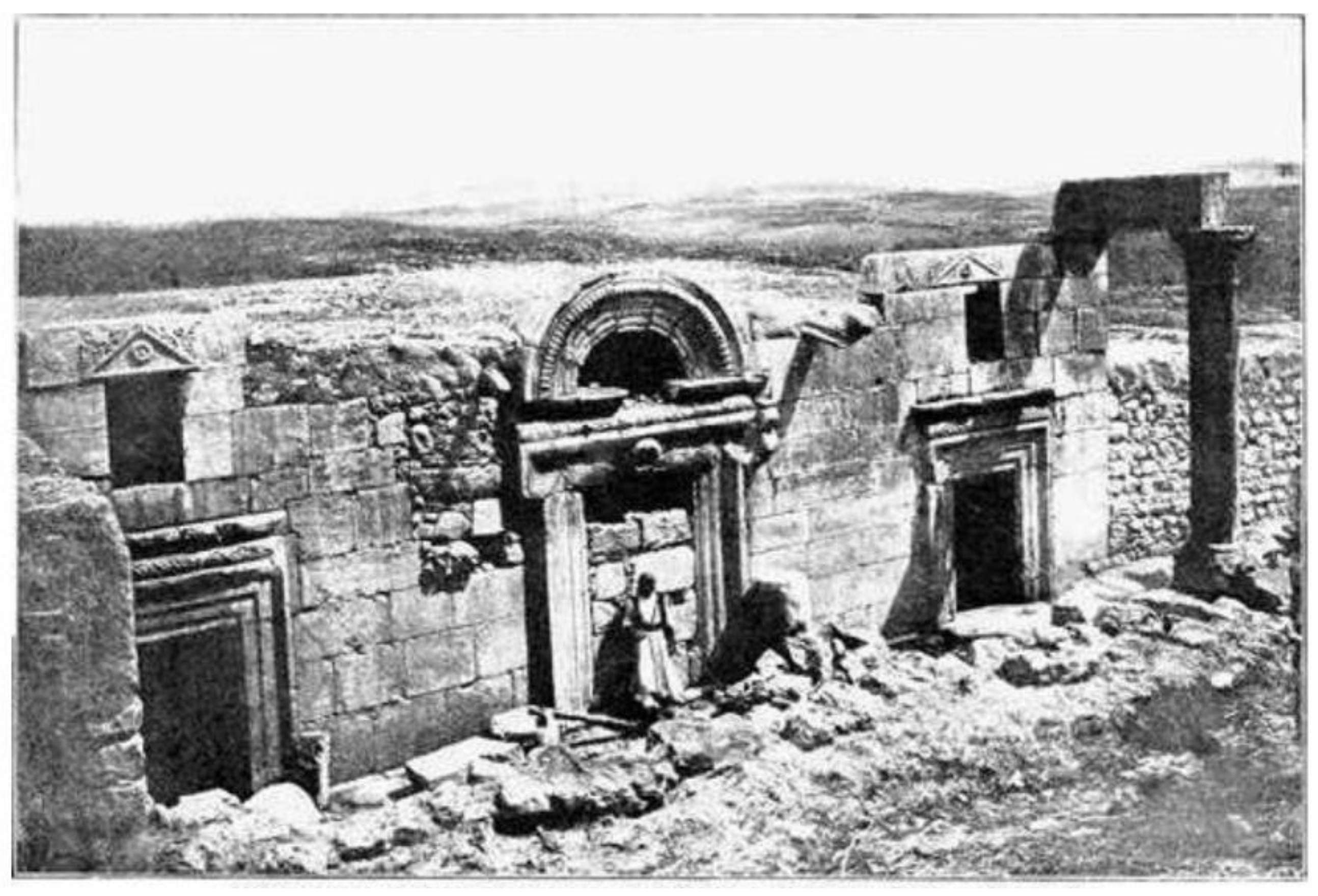

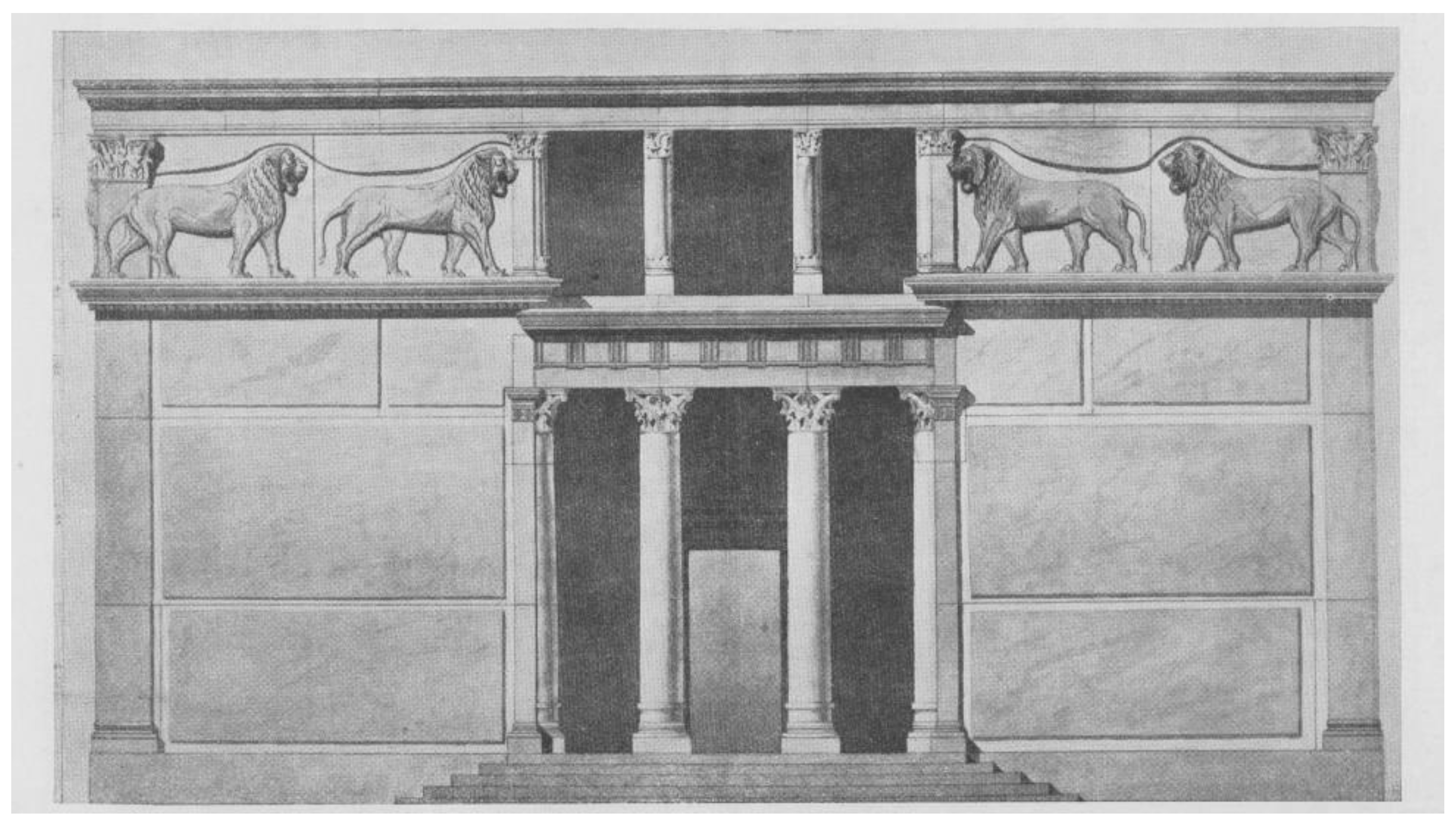

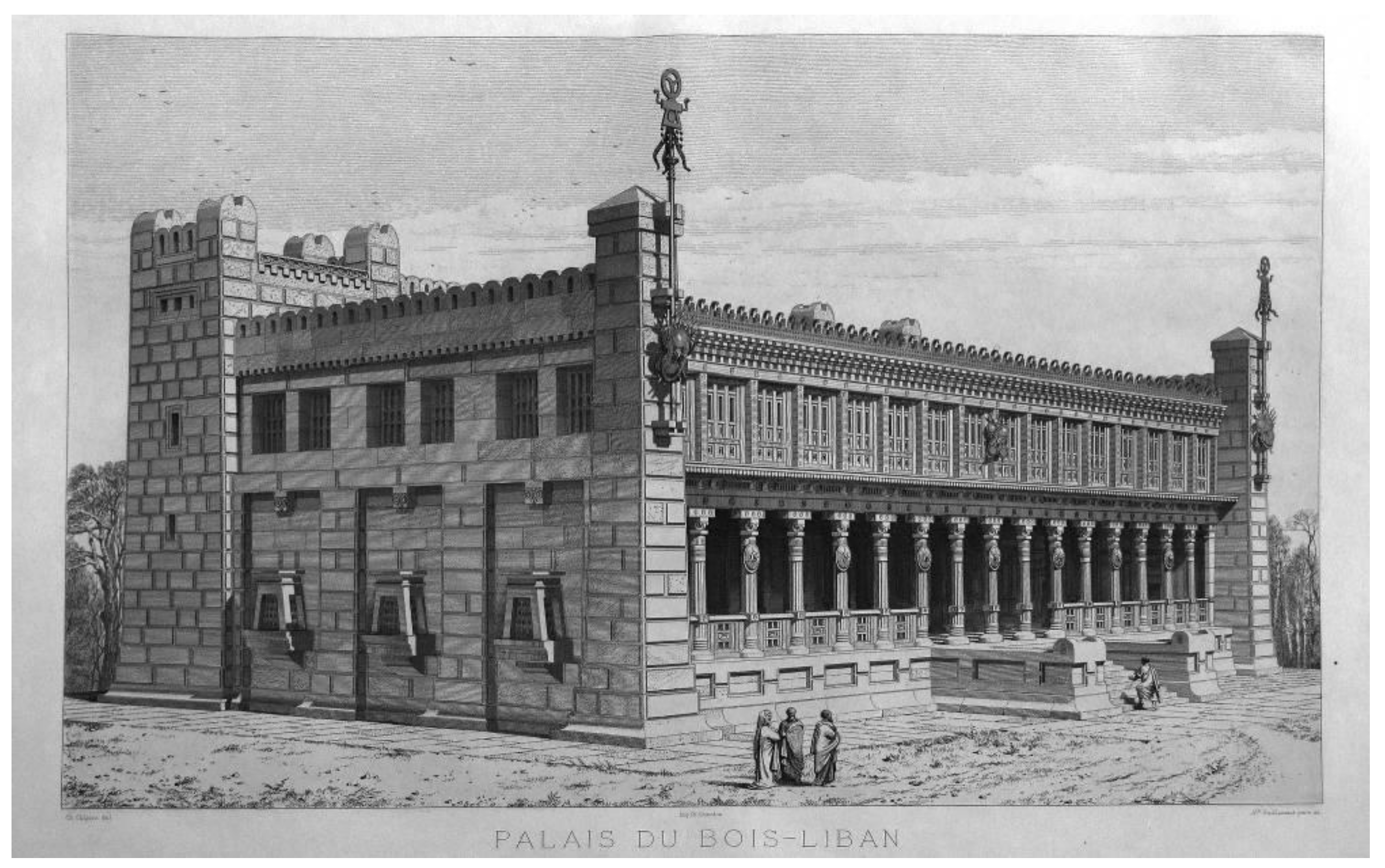

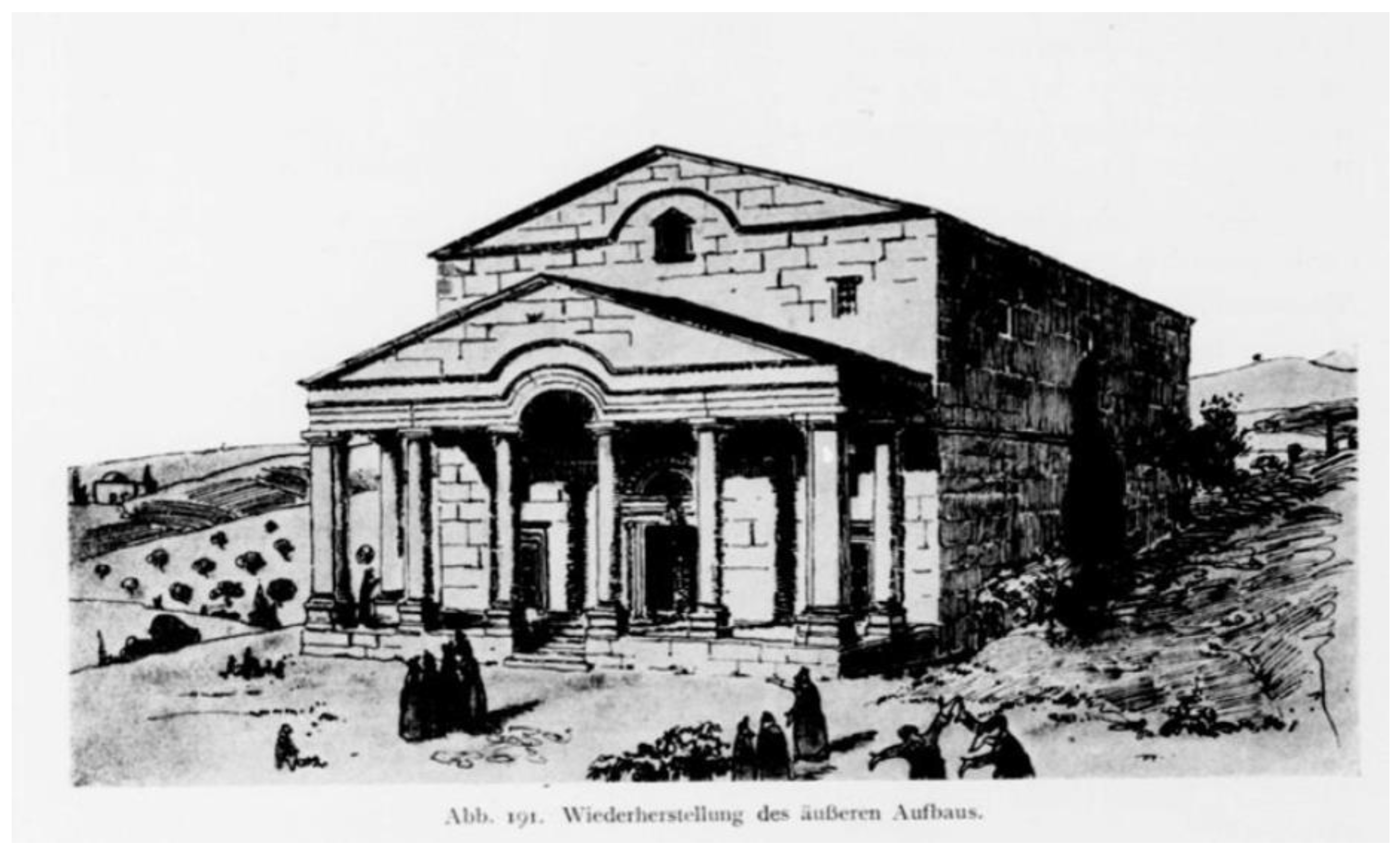

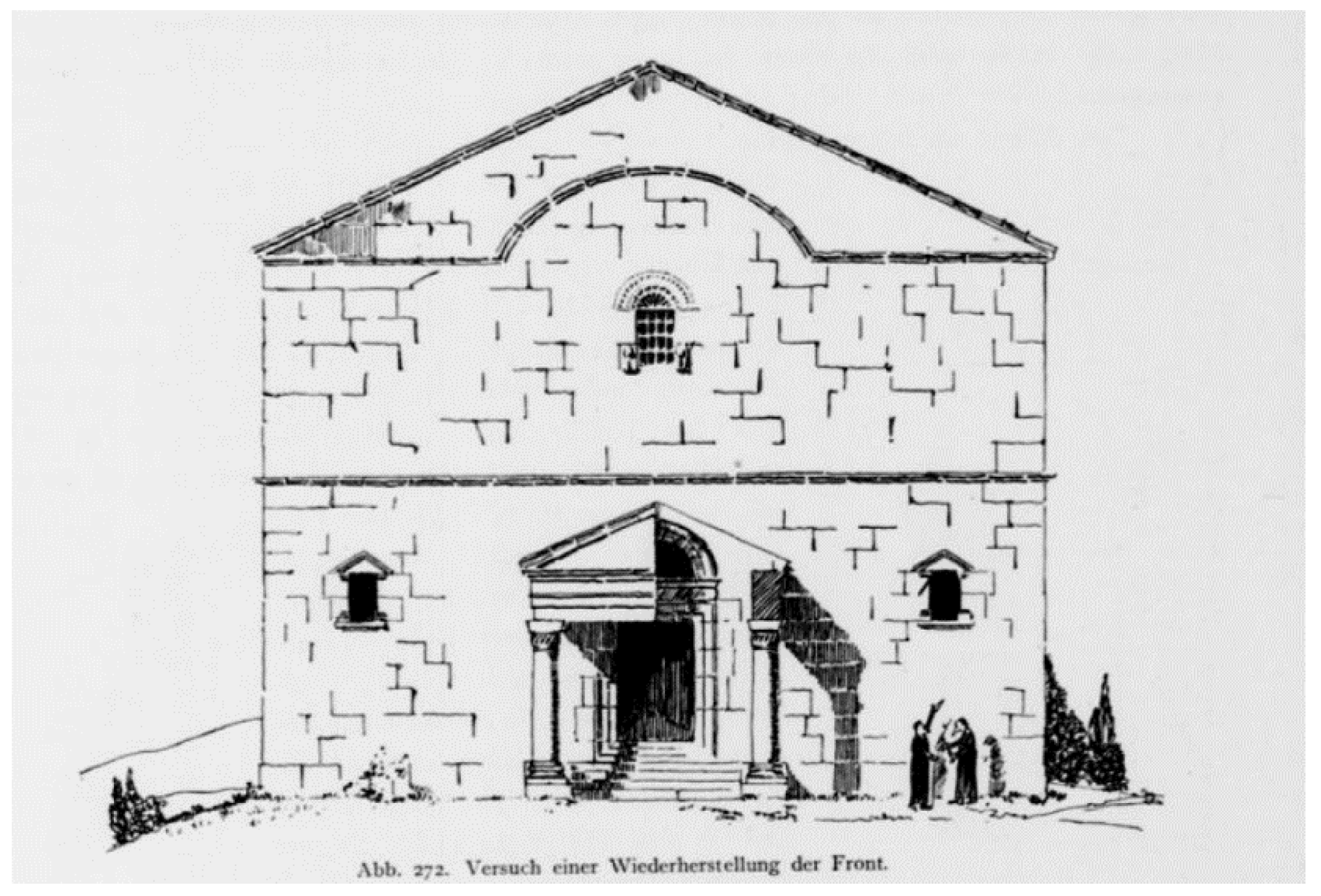

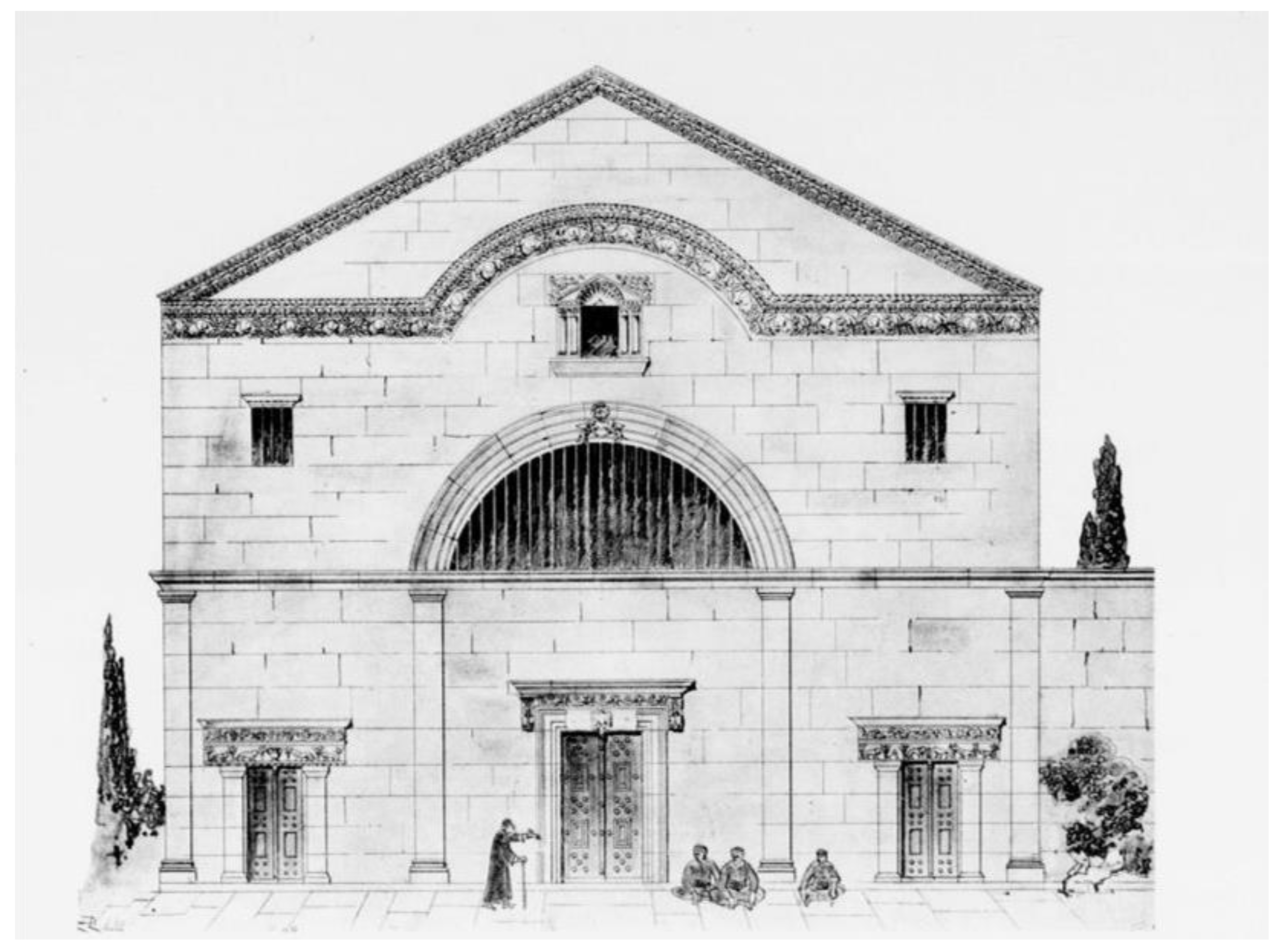

2. Synagogues in Ancient Israel as a Source for Modern Synagogue Architecture

3. Archeological Inspirations and Synagogue Architecture in Latvia

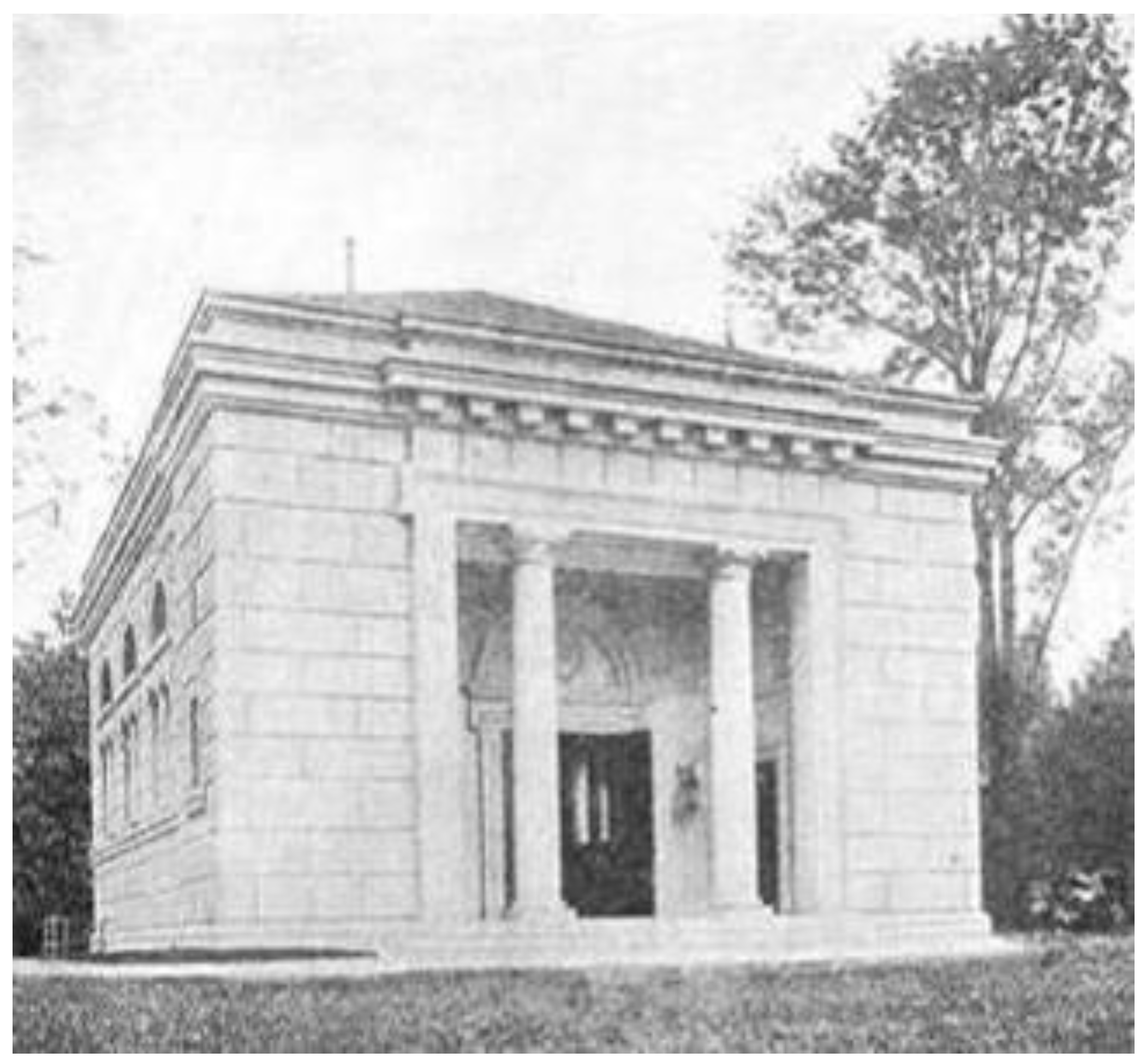

The Peitavas Street Synagogue in Riga

4. Synagogues on the Baltic Riviera

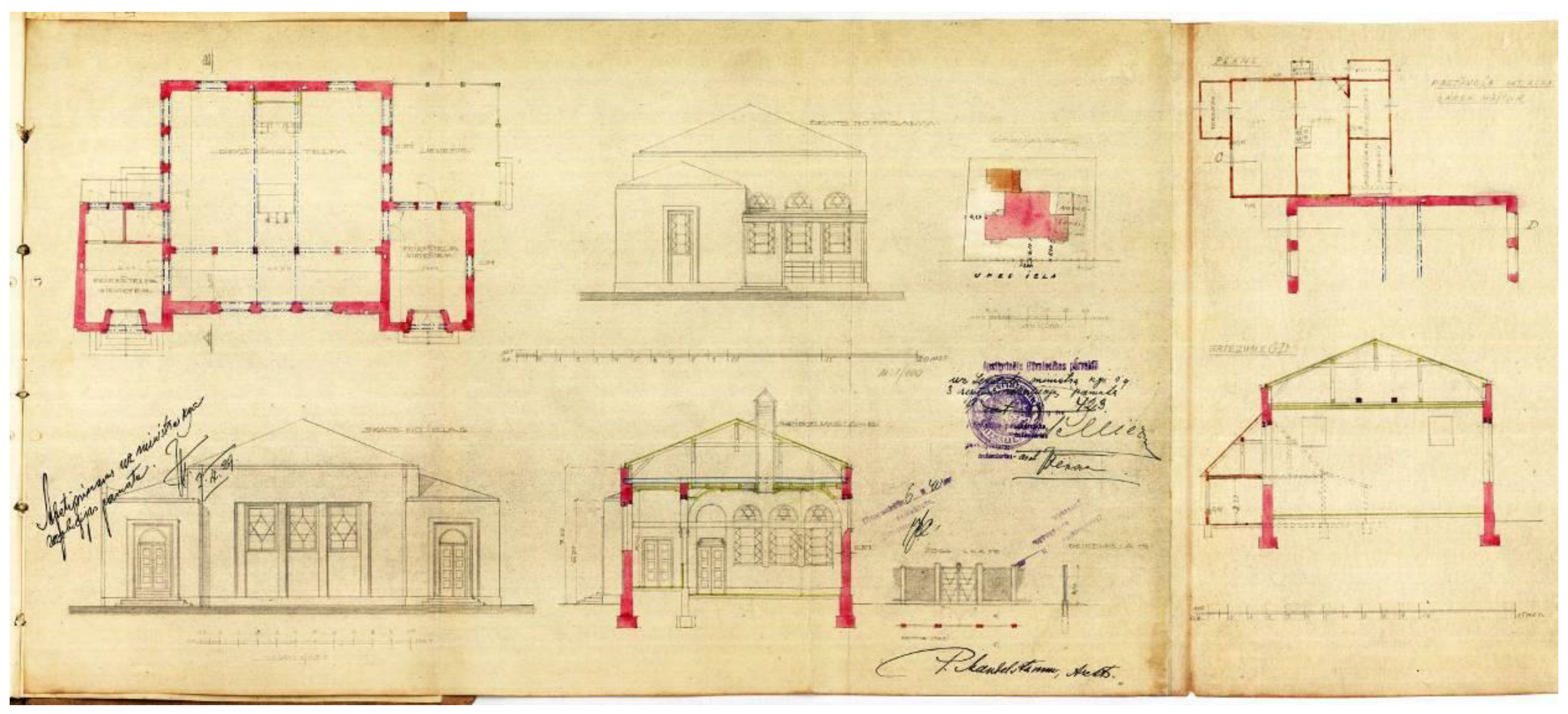

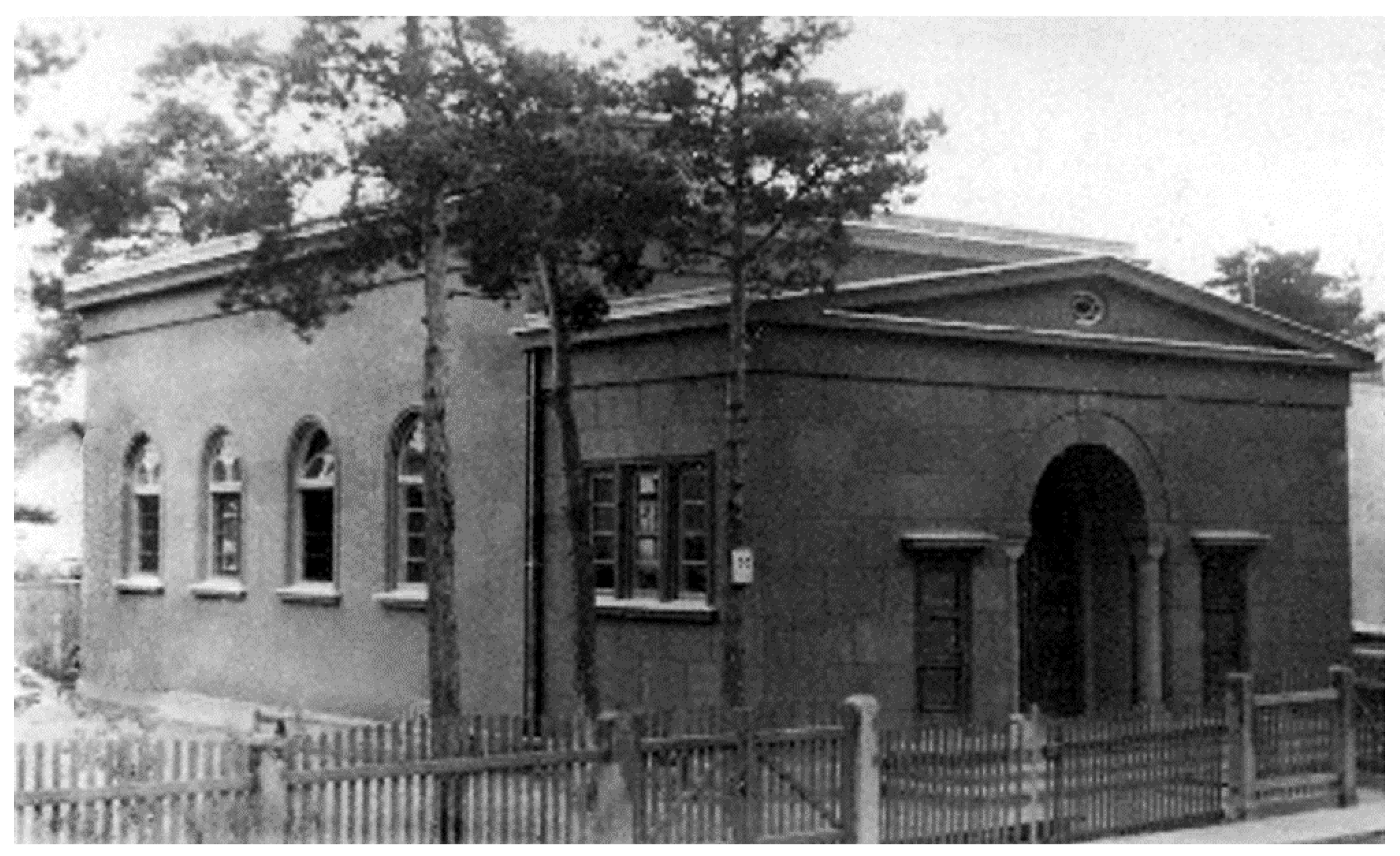

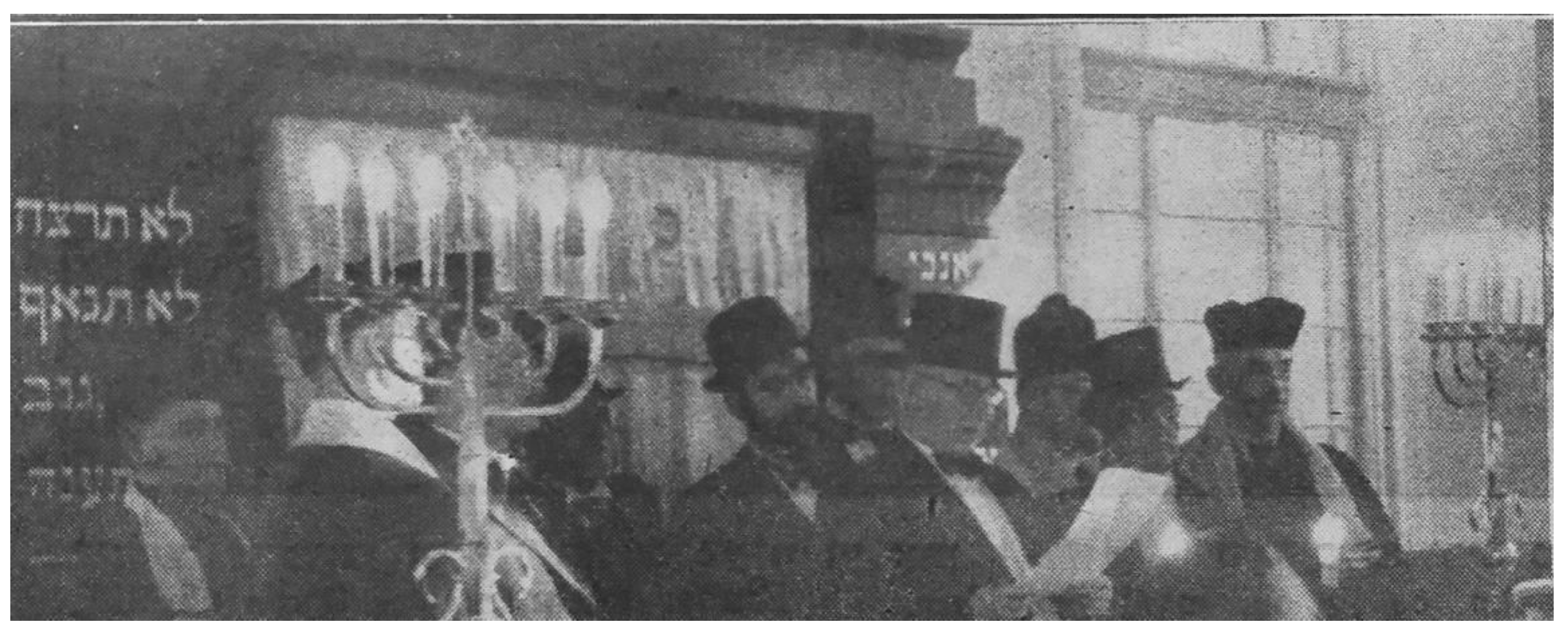

The Hasidic Kloyz in Bauska

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Addison, Lucy. 1986. Letters from Latvia. London: Macdonald. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Cyrus. 1905. Brunner, Arnold William. In Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk and Wagnalls Company, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Cyrus, and Abraham Simon Folf Rosenbach. 1905. Philadelphia. In Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk and Wagnalls Company, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1900. Palästina Album: Ansichten vom Heiligen lande, aus jüdischer Geschichte und jüdischen Leben, sowie Bilder mehrer berühmten Männer in Israel mit berschriebenden Text. Warsaw: Jakub Lidski. [Google Scholar]

- Awin, Józef. 1927. Al omanut ha-beniyah ba-eretz-Israel (On the Art of Building in the Land of Israel). Binyan ve-ḥaroshet 3–4: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bacher, Wilhelm, and Lewis N. Dembitz. 1905. Synagogue. In Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk and Wagnalls Company, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- BBLD (Baltisches Biografisches Lexikon Digital). n.d. Seuberlich, Karl Rudolf Hermann* (1878–). Available online: https:/bbld.de/Seuberlich-Karl-Rudolf-Hermann-1878-1938 (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Bernfeld, Simon. 1913. Synagogue. In Evreiskaia entsikopedia. St. Petersburg: Brockhaus and Efron, vol. 14. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, Rita. 2004. Latvia: Synagogues and Rabbis, 1918–1940. Riga: Shamir. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, Arnold W. 1907a. Synagogue Architecture, I. The Brickbuilder 16: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, Arnold W. 1907b. Synagogue Architecture (concluded). The Brickbuilder 16: 37–44, plates 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Brittany Paige. 2011. Reassessing Stripped Classicism within the Narrative of International Modernism in the 1920s–1930s. Master’s thesis, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA, USA. Available online: http://ecollections.scad.edu:d1000695 (accessed on 27 July 2018).

- Butler, Howard C. 1907. Ancient Architecture of Syria. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Canina, Luigi. 1845. Ricerche sul genere di architettura proprio degli antichi giudei ed in particolare sul tempio di Gerusalemme. Rome: Canina. [Google Scholar]

- Čaupale, Renāte. 2017. Parallels and Analogies in Interwar Architecture in Latvia and Czechoslovakia. Scientific Journal of Latvia University of Agriculture: Landscape Architecture and Art 10: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipiez, Charles, and Georges Perrot. 1887. Histoire de l’art dans l’Antiquité, Égypte, Assyrie, Perse, Asie mineure, Grèce, Etrurie, Rome, vol. 4, Judée, Sardaigne, Syrie, Cappadoce. Paris: Hachette. [Google Scholar]

- Chipiez, Charles, and Georges Perrot. 1889. Le Temple de Jérusalem. Paris: Hachette. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn-Wiener, Ernst. 1929. Die jüdische Kunst: ihre Geschichte von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Berlin: Kunst Kammer. [Google Scholar]

- Conder, Claude R., and Horatio H. Kitchener. 1881. The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoir of the Topography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- De Vogüé, Melchior. 1864a. Le Temple de Jérusalem, monographie du Haram-ech-Chérif, suivie d’un Essai sur la topographie de la Villesainte. Paris: Noblet & Baudry. [Google Scholar]

- De Vogüé, Melchior. 1864b. Ruines d’Araq-el-Émir. In Revue Archéologique. New Series; Paris: Librairie académique—Didier, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2002. Arnold Brunner’s Henry S. Frank Memorial Synagogue and the Emergence of ‘Jewish Art’ in Early Twentieth-Century America. American Jewish Archives Journal 54: 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2005. Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, John, Hugh Honors, and Nikolaus Pevsner. 1999. The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 5th ed. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, Ludwig. 1859. Das israelitische Bethaus in der Wiener Vorstadt Leopoldstadt. Allgemeine Bauzeitung 24: 14–16, plates 230–5. [Google Scholar]

- Grosa, Sylvija. 2012. Rethinking National Romanticism in the Architecture of Riga at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Kunstiteaduslikke Uurimusi 21: 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Samuel D. 2003. American Synagogues: A Century of Synagogues and Jewish Community. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Samuel D. 2011. Arnold W. Brunner and the New Classical Synagogue in America. Jewish History 25: 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnt. 1937. Di impozante grundshtain-leigung fun nayem minyan in Bulduri (Imposing ceremony of laying the foundation stone of the new synagogue in Bulduri. Hajnt, January 25, 2. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajnt. 1938a. Vi azoi yidn hobn ofgeboit a prakhtikn mokom kodesh in an ort, vo zain hobn prier kain drisas ha-regel nit gehat (How the Jews have built a beautiful sacred place in the site, where they previously could not step). Hajnt, August 11, 4. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajnt. 1938b. Haynt groise khanukes-habayis-fayerung fun nayem buldurer minyan (Today: A great inauguration of the new synagogue in Bulduri). Hajnt, August 14, 2. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajnt. 1938c. Der kol ya’akov darf vern tsurik unzer klei-zayn (The voice of Jacob to become again our weapon). Hajnt, August 16, 2. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajnt. 1938d. Zontik—khanukas habayis fun nayem buldurer minyan (Sunday: Inauguration of the new synagogue in Bulduri). Hajnt, September 8, 4. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajnt. 1939a. Di yidn in Mayori veln hayntikn zuntog zikh masameyekh zayn afn khanukes ha-bayis fun der ney-oysgeboyter shul (The Jews in Majori celebrate this Sunday the inauguration of their new-built synagogue). Hajnt, August 4, 4. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Hajnt. 1939b. Khanukes ha-bayis fon nayem minyan in Mayori. Hajnt, August 7. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Rabbi Yom-Tov Lipmann. 1602. Tsurat Beit ha-Mikdash (Shape of the Temple). Prague, unpaginated. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hirt, Aloys. 1809. Der Tempel Salomon’s. Berlin: Johann Friedrich Weiss. [Google Scholar]

- JewishGen. n.d. Available online: https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/jgdetail_2.php (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Kadish, Sharman. 2011. The Synagogues of Britain and Ireland: The Architectural and Social History. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, Heinrich, and Karl Watzinger. 1916. Antike Synagogen in Galilaea. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlyar, Eugeny. 2015. Riga–Sankt-Peterburg–Khar’kov: Istoki i vzaimosviazi ‘evreiskoi arkhitektury’ Yakova Gevirtsa (Riga–Sankt-Peterburg–Kharkov: Sources and i’nterconnections of Yakov Gevirts’s ‘Jewish architecture’). In Evrei v meniaiushchemsia mire: Materialy mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii (Jews in a Changing World: Materials of an International Conference). Edited by Herman Branover and Ruvin Ferber. Riga: Shamir, vol. 8. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Krautheimer, Richard. 1927. Mittelalteriche Synagogen. Berlin: Frankfurter Verlag-Anstalt. [Google Scholar]

- Kravtsov, Sergey R. 2005. Juan Bautista Villalpando and Sacred Architecture in the Seventeenth Century. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 3: 312–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kravtsov, Sergey R. 2008. Reconstruction of the Temple by Charles Chipiez and Its Applications in Architecture. Ars Judaica: The Bar-Ilan Journal of Jewish Art 4: 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kravtsov, Sergey R. 2018. Architecture of ‘New Synagogues’ in East-Central Europe. In In The Shade of Empires: Synagogue Architecture in East Central Europe. Weimar: Grünberg Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kravtsov, Sergey R. 2018. Wooden Synagogues of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: Between Polish and Jewish Narratives. In In The Shade of Empires: Synagogue Architecture in East Central Europe. Weimar: Grünberg Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky, Carol H. 1985. Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Dov, ed. 1988. Pinkas ha-kehilot: Latviyah ve-estoniyah (Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities: Latvia and Estonia). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Mandelstamm, Paul. 1903. Kultusbauten der Ebräer. In Riga und seine Bauten. Edited by Rigaschen Technischen Verein and Rigaschen Architekten-Verein. Riga: Rigaschen Technischen Verein und Rigaschen Architekten-Verein, pp. 188–90. [Google Scholar]

- Meler, Meir. 2015. Buldurskaia sinagoga: Istoriia ee vozvedeniia i unichtozheniia. (Bulduri Synagogue: A history of its construction and destruction). In Evrei v meniaiushchemsia mire: Materialy mezhdunarodnoi konferentsii (Jews in a Changing World: Materials of an International Conference). Edited by Herman Branover and Ruvin Ferber. Riga: Shamir, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Pasta un telegrafa departaments. 1940. Latvijas 1940. g. telefona abonentu Saraksts. Riga: Pasta un telegrafa departaments. [Google Scholar]

- Pommer, Richard. 1983. The Flat Roof: A Modernist Controversy in Germany. Art Journal 43: 158–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renan, Ernest. 1864. Mission de Phénicie. Paris: Imprimere Impériale, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Edward, and Eli Smith. 1841. Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai, and Arabia Petræa. Boston: Crocker and Brewster. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Edward, and Eli Smith. 1856. Biblical Researches in Palestine and Adjacent Countries: A Journal of Travels in the Year 1852, 2nd ed. Boston and London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, Harry. 1908. America. In Evreiskaia entsikopedia. St. Petersburg: Brockhaus and Efron, vol. 2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Segodnia. 1937. Torzhestvo zakladki novoi sinagogi (Solemn laying the foundation stone of the new synagogue). Segodnia, January 26, 4. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Segodnia. 1938. Na vzmor’e zaregistrirovano bolee 37,000 dachnikov (More than 37,000 holidaymakers recorded at the seaside). Segodnia, August 9, 5. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Segodnia vecherom. 1937. Proekt zdaniia sinagogi, zakladka kotorogo sostoialas’ vchera v Bulduri (The synagogue building project: The foundation-stone laying ceremony that took place yesterday in Bulduri). Segodnia vecherom, January 25, 6. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Soo, Lydia M. 1998. Wren’s “Tracts” on Architecture and Other Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stieglitz, Christian L. 1834. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Ausbildung der Baukunst. Leipzig: Gustav Scharschmidt, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Villalpandus, Ioannes Baptista, and Hieronymus Pradus. 1604. Ezechielem explanationes et apparatus urbis ac templi Hierosolimitani: Commentarii et emaginibus illustratus opus, vol. 2, Rome.

- Vitto, Fanny. 1997. Synagogues in Cupboards. Eretz Magazine 52: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, William R. 1904. The American Vignola, 5th ed. Scranton: International Textbook Company, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wörster, Peter. 2008. Der Vater der baltischen Kunstgeschichte: Wilhelm Neumann–Architekt, Kunsthistoriker und Denkmalpfleger. Jahrbuch des baltischen Deutschtums 55: 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yiddishe bilder. 1938. Di bilder zaynen grupirt loitn alef-bet (Aphabetically arranged portraits). Yiddishe bilder, November 18, unpaged. (In Yiddish) [Google Scholar]

| 1 | On this trend see, for instance, (Krinsky 1985, pp. 73, 77; Kadish 2011, pp. 70–74). On a pre-Enlightenment theory of architecture as a divinely inspired art, see (Soo 1998, p. 169). For theoretical reconstructions of the Jerusalem Temple as a derivative of Egyptian architecture, see (Hirt 1809; Stieglitz 1834; Canina 1845). |

| 2 | On the use of this iconography in synagogue architecture, see (Kravtsov 2008). |

| 3 | Ezekiel’s prophesy to “make known unto them [the house of Israel] the form of the house […]; that they may keep the whole form thereof, and all the ordinances thereof, and do them” (Ezek. 43:11) was commented by Rashi (1040–1105): “They will learn the matters of the measurements from your mouth so that they will know how to do them at the time of the end.” Rashi’s Commentary on Tanakh holds that this prophecy does not refer to return of Jewish exiles led by Ezra, “for their repentance was not suitable.” Rabbi Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller (1602) reaffirmed this view and the eschatalogical meaning of Ezekiel’s prophesy in his Tsurat beit ha-mikdash (Shape of the Temple). |

| 4 | On surveys of ancient synagogues, see (Vitto 1997). |

| 5 | For a detailed reconstruction of the palace in Araq-el-Emir, see (Butler 1907, plates 1, 2). De Vogüé explained the inverse architectural orders used in the Jerusalem Temple in historical terms, by the fact that this building dated from before the codification of the orders by Vitruvius in 30–10 BCE; Villalpando had ascribed the supposed inverse orders in the Temple to divine inspiration. |

| 6 | English translation: Jewish Art: Its History from the Beginning to the Present Day. Afterword by Hannelore Künzl; translated by Anthea Bell (Northamptonshire, 2001). |

| 7 | See, for instance, photographs of the synagogues in Kfar Baram, Meron, Nabratein, Tell Hum, Ashdod, and Chorazin, in (Cohn-Wiener 1929, pp. 81–85, 88, 90–91). |

| 8 | Seuberlich received his architectural education at the Riga Polytechnic Institute (Polytechnischen Institut zu Riga) in 1898–1904. Besides the Peitavas Street Synagogue, he is known for his restoration of the medieval Kuresaare Castle (1904–1912, with Neumann), and Riga Zoo. Latvian State Historical Archives, 7175-1-256; (BBLD n.d.). |

| 9 | Neumann, an architect, art historian and curator, was educated at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts (1875–1876) and received his Ph.D. from Leipzig University. Besides the Peitavas Street Synagogue, he prepared the initial design for Richard Wagner’s Villa Wahnfried (1870), built Lutheran churches in Daugavpils (Dinaburg, Dvinsk, 1892–1893), Kuldīga (Goldingen, 1892–1904), and Kabile (Kabillen, 1904–1907) and designed Riga Art Museum (ca. 1905). See (Wörster 2008; BBLD n.d.). |

| 10 | The Russian imperial government granted residence rights on the Baltic Riviera to the following categories of Jewish citizens: “honorary citizens,” burghers of the nearby town Sloka (Schlock), military veterans, and the families of merchants of the First Guild (which included well-to-do Jews). The local overlord of Majori (Majorenhof), Baron Ernst H. G. von Fircks (1843–1919), explicitly discriminated against Jews by refusing to let property to them. See (Meler 2015, pp. 257–8). |

| 11 | By the end of the 1930s, the Jewish congregation in Majori numbered 210 (Bogdanova 2004, p. 168). The general number of holidaymakers in Majori and neighboring Dzintari (named Edinburgh until 1922) reached 14,925 in August 1938 (Segodnia 1938). |

| 12 | On Lezhik’s date and place of birth, see (JewishGen n.d.). |

| 13 | Yad Vashem testimony, item ID 3938210. |

| 14 | Latvian National Historical Archives (Latvijas Nacionāls arhīvs Latvijas Valsts vēstures arhīvs, hereafter LNA LVVA), 140-6343-14-202-6. The house number is not specified in this document. |

| 15 | LNA LVVA, 2761-3-13547. |

| 16 | LNA LVVA, 140-6343-14-202-6. |

| 17 | LNA LVVA, 140-6343-14-202-10. |

| 18 | LNA LVVA, 140-6343-14-202-6l. |

| 19 | Services in the Majori Synagogue were reported already on 19 and 20 August 1938; Hajnt 194 (19 August 1938), p. 3. Its was only inaugurated on 5 August (20 Av) 1939 (Hajnt 1939a, p. 4; 1939b). |

| 20 | On their identities, see (Yiddishe bilder 1938). |

| 21 | This was proved by an investigation undertaken by Zoya Arshavsky and the author of the present article in 2010. |

| 22 | See, for instance, the villa at 40 Meža Boulevard in Riga, built by Mandelstamm in 1930. |

| 23 | The Riga telephone directory listed Bernards Kļaviņš without mentioning his profession (Pasta un telegrafa departaments 1940, p. 308). |

| 24 | See Yad Vashem witness testimony no. 68217 for biographical data on Abram Ragol. He was deported by the Soviets and died in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Siberia, in 1942. |

| 25 | The information on the cupola, which was omitted on request of a Riga rabbi, was published by the late Meyer Meler (2015, p. 264). Meler did not mention any source of this information. It is possible that some roof superstructure in seen in a low-resolution photograph of the synagogue (Figure 16). |

| 26 | The “rustication” is visible in the photograph (Figure 16) and was mentioned in the newspaper report (Hajnt 1938d). We deduce the fact that the Bulduri Synagogue was made of wood from the fact that it was burned down during the Second World War, on 21 July 1941 (Addison 1986, pp. 46–47; Meler 2015, pp. 265–68). |

| 27 | LNA LVVA, 140-6343-16-62-5. |

| 28 | For definition of crossettes, see (Ware 1904, p. 17). For the portal of the small synagogue in Kfar Baram, see (Cohn-Wiener 1929, p. 85). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kravtsov, S.R. Synagogue Architecture of Latvia between Archeology and Eschatology. Arts 2019, 8, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030099

Kravtsov SR. Synagogue Architecture of Latvia between Archeology and Eschatology. Arts. 2019; 8(3):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030099

Chicago/Turabian StyleKravtsov, Sergey R. 2019. "Synagogue Architecture of Latvia between Archeology and Eschatology" Arts 8, no. 3: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030099

APA StyleKravtsov, S. R. (2019). Synagogue Architecture of Latvia between Archeology and Eschatology. Arts, 8(3), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030099