1. Introduction

Studies that aim to investigate the feminine avant-garde of the 20th century have become more numerous as well as more known. For Italy, this optic especially regards the role women assumed within the Futurist movement

1. Meanwhile, this research has intersected with the contribution women have made to the decorative arts

2. This essay seeks to add another tessera to this intricate mosaic by introducing the work of Fides Testi in Italy during the 1930s in textile arts, with particular attention to the airbrushing technique which she often used, earning her a certain measure of fame.

In Italy, the affirmation of women in the arts with a professional attitude occurred, except for rare precocious exceptions, especially after the First World War alongside the conditions for a broader, more general transformation of women’s role within society. Called to substitute men who were out in the front in the workplace, women gradually obtained greater self-awareness, confidence and independence in every aspect of life, and therefore also in artistic affairs which converted from a dilettante hobby for upper-class women to becoming a genuine and personal professional activity.

Right after the war, critics, artists and artistic industries in Italy sought to revalue and refashion applied arts in the attempt to disentangle it from the predominant production in historic styles for use in foreign markets and redirect it towards the ways and solutions offered by national folklore, by a rethinking of classical styles and the updating from international novelties, from Futurism, etc.

Therefore it is especially in post-war Italy that a large number of female figures (scant compared to contemporary experiences in Europe) found an outlet in the arts and the applied arts. It was particularly Futurism, whose mission of artistic intervention encompassed every element of daily life from furnishings to fashion (as was already indicated in the 1915 manifesto Ricostruzione Futurista dell’Universo), to stimulate the design fervor and creativity of women, especially in the so-called “arts of the thread.” Although the “arts of the thread” were considered the field the most consonant and appropriate for women, traditionally linked with manual labor and female domestic industriousness, the artists succeeded in introducing interesting innovative elements and expressing through it formal, iconographic and technical research.

Fides Stagni should be included among the female figures who played a role in Italian decorative arts just after the war. She received a traditional education in Bologna at the Accademia di Belle Arti but became an advocate of Second Futurism, arriving to Rome around 1928 with her husband, the painter Carlo Vittorio Testi (1902–2005)

3. Even though like her husband she veered towards Futurism, Fides made choices also quite her own. It is significant that she chose to sign her name as “Fides Testi” but often only with the first name “Fides” even before separating from her husband.

Fides worked in the late 1920s in Rome, one of the propulsive centers of Second Futurism as well as of the rebirth of decorative arts. As she herself expressed in an interview, upon arriving to Rome she became enthusiastic from visiting the Futurist exhibitions because she had felt that art “befitting the aspirations towards something new” (

Mitrano 1989)

4. In particular Fides drew closer to the language of aeropittura (painting from an airplane), like other women artists of the time because they saw in it a freedom of expression just as if they were experiencing firsthand the experience of flying, thrilling adventure, and release from the domestic walls. Nevertheless, it must be stated that Fides only partially adhered to the modes and themes of the Futurists because, as Anton Giulio Bragaglia observed in 1934, in introducing at his gallery a personal exhibition of her paintings, some of her visions are difficult to place and define, resulting neither as Futurist, Surrealist, nor abstract but as the expression of a spiritual urgency, apparitions and suggestions realized by spraying, evocations of a “soft, silky cocoon” (

Bragaglia 1934). More than in the themes, in fact, which were only in part connected to the Futurist iconography, Fides’s participation in the avant-garde movement should be studied in the choice of taking hold of the modern mechanical airbrush instrument and in the particular effects the tool was able to create. Using the airbrush Fides and her husband were considered “innovators” since they succeeded in “obtaining effects of transparency according to the Futurist style which were absolutely impossible to obtain by pictorial means”, as she herself declared looking back (

Mitrano 1989).

For Fides, too—in a parallel path to other women artists of the time—the practice of painting coexisted with the constant and appreciated activity of textile designer and maker for fashion and decor, even if she declared to have embraced the applied art “for financial reasons” that is for making money once her Futurist paintings no longer sold (

Mitrano 1989).

Although Fides’s participation in important occasions for exhibition is documented

5, it was at the same level as the attention she aroused as a textile decorator, both with more traditional techniques of embroidery but applied with designs of modern taste and with the use of the airbrush.

Given that the so-called “arts of the thread” were considered an exclusively female endeavor, Fides was a woman painter who was well acquainted with embroidery work

6 but, in the climate of technical and formal experimentation of the second Futurism, she decided to take on the challenge of the modern compressed-air instrument. Fides was able to use the airbrush on different types of surfaces: in paintings, on paper and, above all, on fabrics. In Italy she was almost exclusively identified with this technique for decorating textiles (although, unlike the German artist Maria May, she never founded a school to teach the method, yet her activity remained limited to the domestic laboratory)

7.

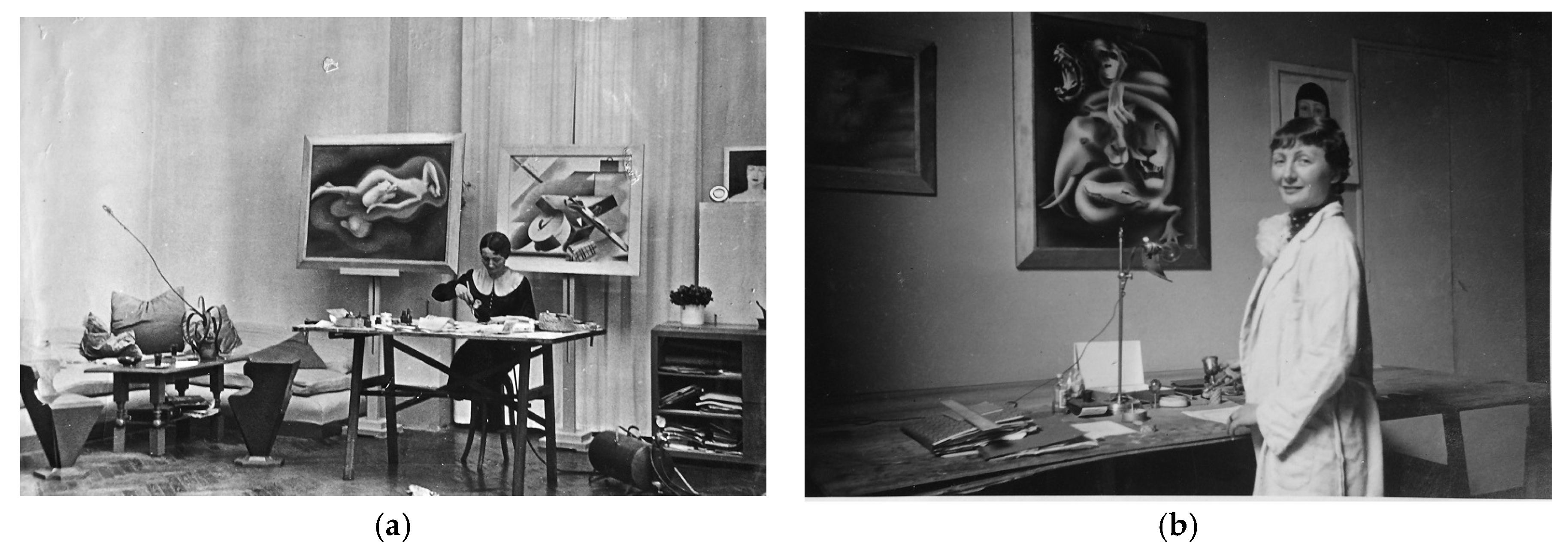

Although we have photographs of Fides taken while she is decorating paper and not textiles, it was certainly this latter material that decreed her success (

Figure 1). Unfortunately though, we were not able to track down her works nor the instruments or colors she used.

2. The Use of the Airbrush and the Aesthetics of Shading in Italian Art in the 1920s and 1930s

When Fides and Carlo Testi adopted the aerograph technique in the late 1920s, it had already been in use in the United States and Europe ever since the beginning of the twentieth century, but only at that time did it start becoming particularly appreciated and widespread in Italy as evinced by the information gathered and products of the time. However, the lack of precise documentation on many of the artists and the Italian artistic industries which adopted it as well as even the lack of exact dating of the works make it impossible to formulate hypotheses about timing in the introduction of the technique and determining what artists used it first. Even research on the vendors of the colors and the tools, initially coming from abroad, especially from Germany, and then produced in Italy, has yielded only partial results since many of the details about the corporate history still need to be reconstructed and their commercial catalogues were often lost once the firm shut down.

We can affirm however, that if the airbrush was already in circulation and production in Italy from the early 1920s, a more artistic use is noted especially around 1928, demonstrating its wide use in the early 1930s.

In 1931, in

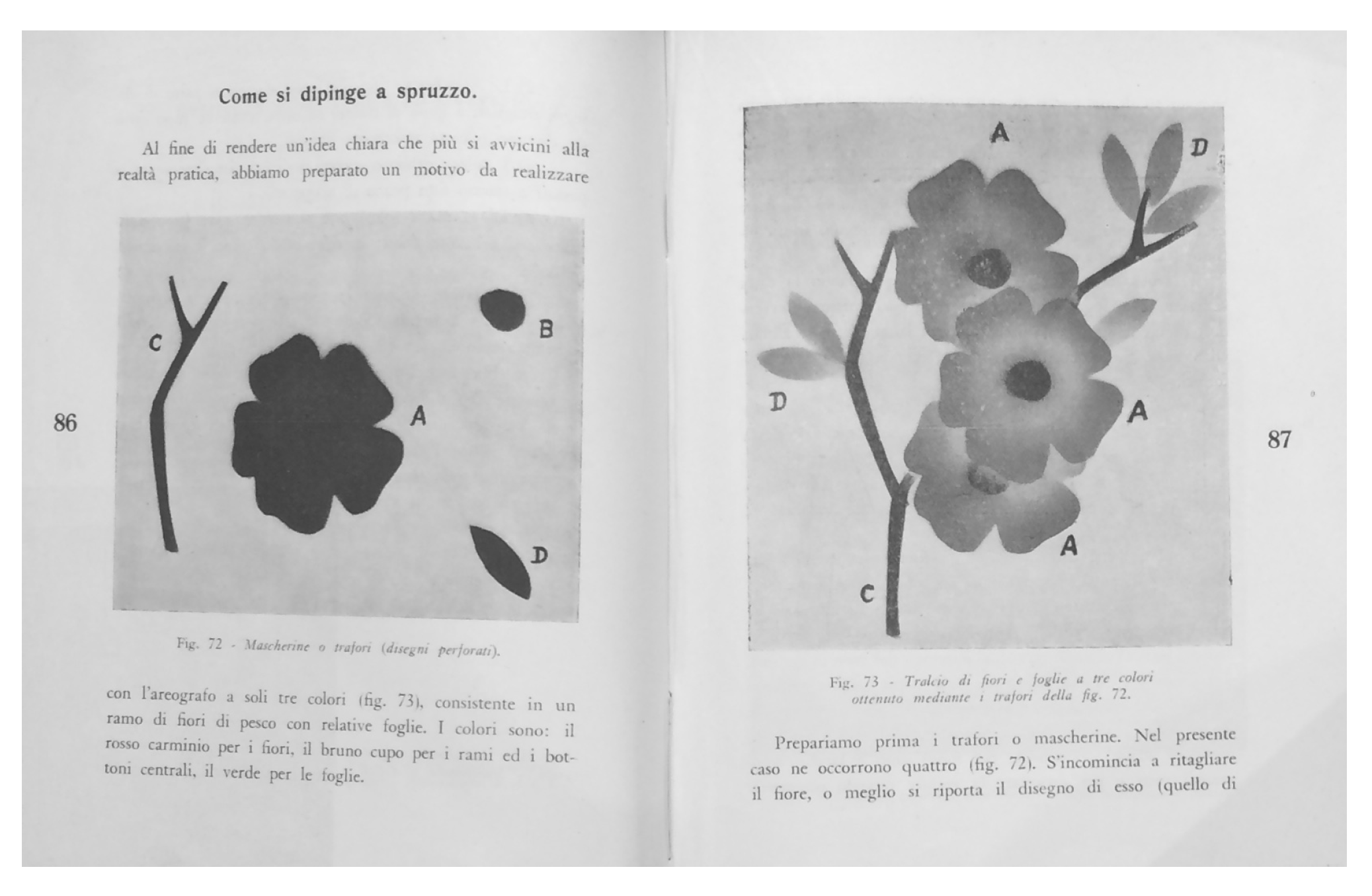

Domus—one of the most important magazines in Italy dedicated to interior decorating—an article appeared concerning the main characteristics of “spray decorating”, a subject that the writer indeed considered “of particular relevance in every branch of the decorative arts” (

Fontana 1931). Although the article recalled that the instrument had actually existed for many years, it was included among the most popular “modern techniques”. The article stated that “in the field of decorative arts the spray technique is particularly suited for the decoration of porcelain, pottery and fabrics”; “these latter are easy to treat and suited also for use by beginners”. Then it went on to give practical advice about the decoration of textiles, about where to buy work tables, equipment and colors, most of which were of German manufacture. The article suggests a special work table patented by the German company “A. Krautzberger & C.” on which one could execute the decoration also on a roll of fabric which could be combined with the fixing and drying equipment. The author informs us that for the fabrics available on the market there are different colors depending on whether it is natural or artificial silk, linen, cotton or mixed fabric. For beginners, she advises some types of colors available from the “Soc. An A.R.C.A.” of Milan which can be dissolved in alcohol and do not require any further treatment after being sprayed, while for the textile industry the best colors are “Indanthren”, which resists light and repeated washings but which require a procedure which would be too complicated for an amateur. She informs us that spraying equipment was made in Italy by the “Vincit” company of Lecco and the “Officine Riunite” of Milan, but the best ones are produced by “A. Krautzberger & C.”, which has a branch in Milan, while the “Gruebe “company of Lipsia also has a representative in Milan in the Conrad-Bartoli.

These indications provided by

Domus prove to be very precious in reconstructing what were the possibilities for artists to procure materials from vendors and producers which must have been concentrated in northern Italy, considering that Milan was home to several important companies: “ARCA” (“Aziende Riunite Coloranti e Affini” United Companies of Colorants and Accessories) founded in 1925 by important German producers of colorants (

Trinchieri 2001, p. 246); Contrad-Bartoli, founded in 1920 and as of 1924 producer of its own spray guns and airbrush pens (

Lavista 2005) (

Figure 2); the company Ferdinando Seminati which produced the aerograph “Vincit” and had its headquarters on Corso Sempione; and finally “Indanthren” whose large offices (

Negozi d’oggi 1930), together with the frequent presence of ads about its colors “of unsurpassed resistance” in major Italian magazines confirm its success.

The broad scope of the

Domus article, the inclusion of the practical aspects and the thoughts of the author concerning the “modernity” of the compressed air instrument confirm the wide-ranging attention given to the artistic use of the airbrush in different contexts from decoration of useful objects to wall decoration

8.

Among the most important examples in Italy in graphics and in painting, we may cite the artist Ivanhoe Gambini (1904–1992), who was active in the environment of the second Futurism (

Scudiero 1991). His first well-known works realized with airbrush date to around 1928, but the consistency with which he dedicated himself to this technique makes him one of its most representative exponents. Furthermore, the care with which his heirs have conserved not only his works but also the documentation and some of the equipment

9 renders Gambini to be a particularly precious tessera for understanding the artistic use of the airbrush in Italy that deserves a deeper, specific study.

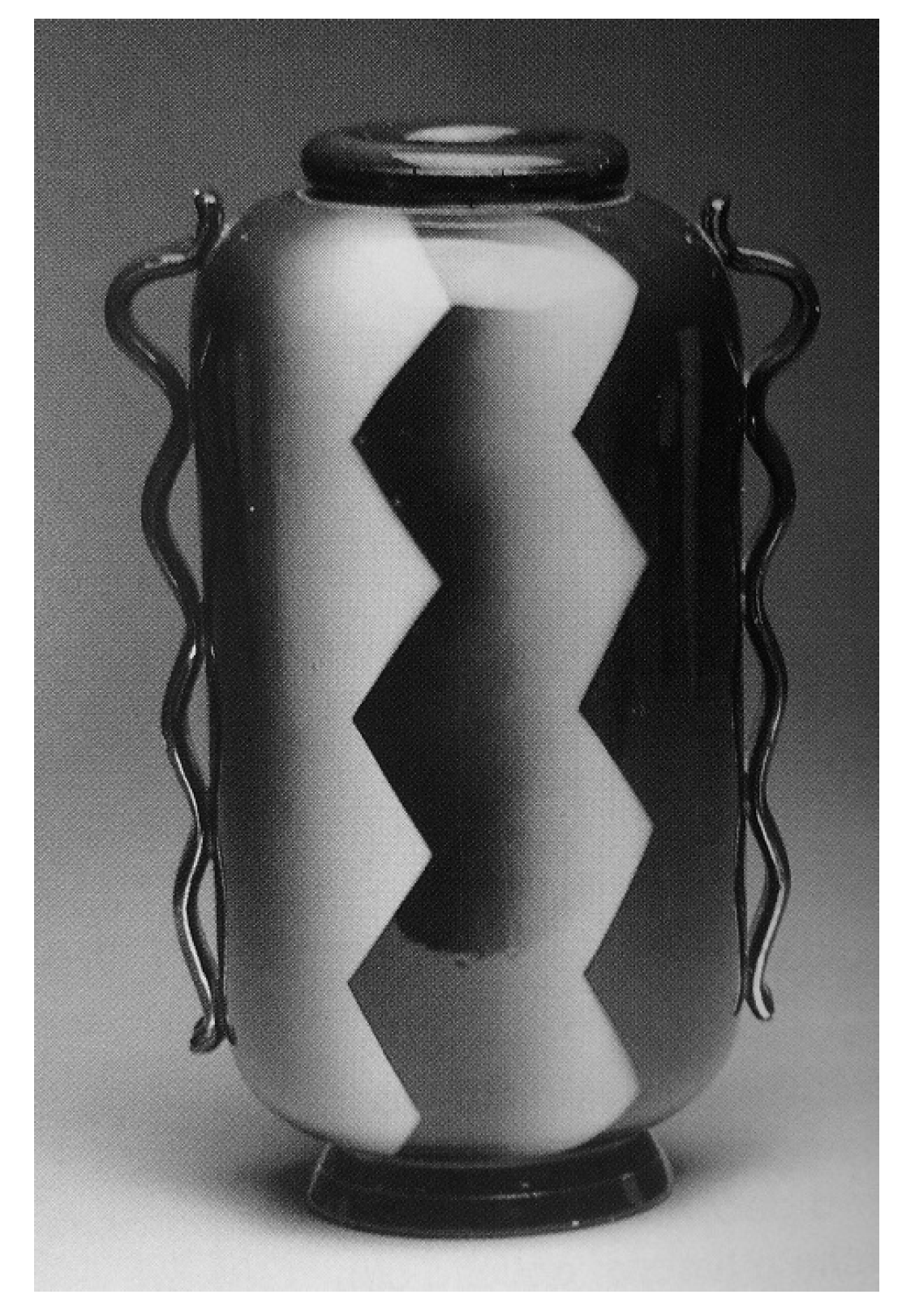

As the ads of the time tell us, confirmed by the products themselves, airbrush decoration was also widespread in ceramics and in textiles. The use of the instrument not only offered indisputable practical advantages to the artistic industries (especially because of the speed and precision it showed in the execution of decorations thanks to the use of stencils), it also achieved aesthetic results which, in abstract motifs like those of figurative inspiration, also coincided with the search for new modes of expression which were by now very distant from the realistic effects for which the instrument was created.

The sharp outlines and the soft shading of the nebulized spray inside of the stencils—effects which were otherwise very difficult to obtain—as well as the volumes rounded by an accentuated chiaroscuro which took on an almost metallic appearance, like that of an auto body, or vaporous effects that were dreamy and lyrical, led to an expression that was sculptural and mechanical, creating a visual effect that was synonymous with Modernity. It is not surprising that spray decoration in Italy was used mainly in the cultural environment of the so-called second Futurism: while it exalted the aesthetics of the machine, it encouraged the modern artist to use new materials and techniques, like that of the airbrush. For example, it is significant that in 1935 the Futurist artist Tullio D’Albisola (1899–1971) invited potters to develop innovative techniques as the aerograph (

D’Albisola 1935), while in 1938 in the Futurist manifesto

Ceramica e Aeroceramica, he describes the “forms and colors that are neither narrative nor descriptive but suggestive” in certain aspects of modern ceramics

10.

The main contributors to the spread of the taste and the aesthetics of spray decorating in Italy were, in fact, the ceramics industries, including the largest ones which were using the airbrush in some sectors of mass production (Richard-Ginori). Others like Galvani of Pordenone under the direction of Angelo Simonetto used spray decoration as its driving theme which allowed it to manufacture a product that was low cost but had a powerful visual impact

11. Starting with

Spritzdekor from Germany many ceramic industries understood the practical advantages of mechanization, also embracing the formal qualities made possible by the airbrush like the capacity for “the subtlest shading with any color” “because all colors can overlap resulting in unexpected effects upon firing”. This was considered a high artistic value obtained not “despite” but rather “because of” the contribution of the mechanical means, as we read in a 1936 manual for ceramic decoration (

Ettorre 1936, pp. 79–94)

12 (

Figure 3).

The “tablecloth” decorations, the geometrical motifs, the shaded intersecting bands, the asymmetrical checkerboards that adorned pottery objects were all also used on contemporary fabrics, both for fashion and interior decorating and represented a common convergence towards a new aesthetic taste (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The major Italian fabrics decorated with an airbrush and made for fashion and interior decoration appeared at the end of the 1920s and were manufactured by industries that not only took advantage of the technique but also adopted the aesthetics, like Borghi of Turin, for example, which was specialized in designs with geometric motifs that were “the triumph of the straight line in all the strangest combinations of geometric figures and bizarre intertwinings” (

Stoffe d’arte italiane 1929) (

Figure 5).

Airbrushed textiles were also made by artists who wished to achieve in textile an expressive power that was not based on weaving or embroidery but on the airy quality of the color, in the distinct combination of clearness and vaporous enchantment.

The use of the airbrush for the decoration of textiles was an operation that technically could be performed by anyone—we may cite, for example, the cushions made by a student at the Decorative Arts Institute in Monza to demonstrate the ease of application of the technique and its widespread use already in the art schools (

Anticipazioni alla Triennale di Monza. Le scuole d’arte italiane 1930;

Felice 1930, tav.116)—and could be compared with the decoration on other materials. It should be mentioned, however, that the knowledge of the ultimate use, the skill in using the instrument and the stenciling systems, the choice of fabrics (often very light-weight ones which better corresponded to the refinement of the decoration) and the graphic layout often brought about results of great equilibrium and elegance.

These qualities are found in the silks printed by Elio Cavalieri, for example, decorated with “blown colors” with a “perfect execution of the shading”, an example of “absolute modernity” of style and an “excellent technical result in a refined creative taste” (

Ponti Vimercati 1929)

13. They are mainly light-colored

crêpe handkerchiefs on which we can see fluctuating wavy lines and symmetrical concentric circles, curving waves erupting, rhythmic lines that spread like clouds or fans and then dissolve into sinuous abstract motifs. Unfortunately, we know about these handkerchiefs only from period photographs, yet from the descriptions we can tell that they were made with a skillful application and combination of colors (

Figure 6).

It has not been possible to reconstruct the airbrush activity of Elio Cavalieri, about whom we only know that he had a textile workshop in Rome (like Fides) and that he had exhibited his textiles at the Monza Triennale of 1930

14. However, for this era, we know a great deal more about the airbrush artistry textile decoration by Fides.

3. Fides and Airbrush Textile Decoration

Fides made her debut as a textile decorator in 1929 exhibiting for the

Boutique Italienne, recently inaugurated in Paris by Maria Monaci Gallenga (1880–1944). Fides and her husband had begun to work in Rome for the company of Maria Monaci Gallenga, and then relocated to Rome, followed by two months in Paris (

Mitrano 1989)

15. Fides had introduced herself to Maria Gallenga around 1928 proposing to her fans decorated in a Japanese style, but Gallenga, according to a story with hints of hagiography, with great intuition and secure judgment, had steered her to develop certain designs that were “personal, informal and in a modern taste” (

Morelli 1930).

Silk fabrics were exhibited in Paris for use both in fashion and for interior decorating: “for pyjamas, neck scarves, umbrellas, purses and cushions but also decorative panels, as we know from an article published in the Italian magazine

La casa bella (

Albano 1929). From the Italian reviewer—and thus surely biased—we know that they were received “with the most sincere applause and enthusiasm by everyone, with unanimous favorable opinions and they immediately won over the difficult and haughty Parisian environment”. Nevertheless, even if these “beautiful and imaginative fabrics decorated with exquisite originality” were described as “a revelation”, they seem more oriented to please the moderate tastes of a bourgeois clientele. As we understand from the black and white images published in the article, decorations were mostly inspired by naturalistic subjects (such as

Orsi [Bears] and

Caprioli [Deer]), sometimes with a nod to the most fashionable themes from modern life (such as

Tennis and

Aereoplani [Airplanes]) and to the world of music (as

Jazz Band and

Serenata), the last ones evoked with a livelier taste of caricature and almost surreal with results that are more subtly ironic or dreamy. They all shared the same refined, vaporous effects, the element which strongly links them to Fides’ contemporary pictorial work within the field of Futurism just as the choice of the instrument of compressed air. Ironically, it is that “mechanical” aspect which made her approach the first aerographs with hesitation which could later be sought after a motive for participation in the poetics of the Futurists (

Figure 7).

The themes selected at that time varied within a range of moderately innovative taste but, it was above all the technique—the “tossing color onto fabric with mechanical means”—that was considered a driver of “the activity and the sensitivity of these dynamic times”, and “something that is neither classical painting, nor painting sugary motifs with the rigidity of the color distributed without skill, nor printing, nor embroidery, nor appliqué”. This is the description that appears in a little book published in 1930 dedicated to interior decorating—

Nella casa del nostro tempo (In the house of our times)—written by an anonymous author using the pseudonym Chiffon—not surprisingly a light and elegant fabric—and entirely illustrated with projects by Fides. Her drawings propose entire interior decorating projects as well as examples of decorative elements and even fashion models that Chiffon considers expressions of the “new sensitivity” (

Chiffon 1930, p. 39).

Among these decorative elements return the musical themes (see also the work behind her desk in

Figure 1a), but we also find examples of research in the direction of geometrical shapes and abstraction which attest to the knowledge and free mixing from varied sources (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

The book by Chiffon offered practical advice for the home, following an increasingly widespread custom of manuals and magazines of the era addressing a wider public, not just specialists, and, in particular, modern women, with the intent of arousing their creative capacity and ability to design. The quintessential publication dealing with rational furnishing is recognized in Italy as being that by Lidia Morelli (1871–1946) in her famous home economics manuals such as

La casa che vorrei avere (The house that I would want) (

Morelli 1931a)

16.

It was Lidia Morelli, also a connoisseur and unflagging promoter of “feminine work” (

Morelli 1933b), who was one of the main proponents of the work of Fides, whom she considered “unusually gifted with decorative imagination” (

Morelli 1931c). Besides publishing reproductions of her creations in the volume

La casa che vorrei avere (

Morelli 1931a,

1933a), it is in the important magazine

La casa bella that Lidia Morelli also published many of those designs which “rarely one encounters in the modern style” (

Morelli 1931b).

If the decorative panels realized with airbrush remain mostly anchored in figurative subjects—with a hint of the fantastic which releases them from a naturalist scheme especially thanks to the soft shading—and are conceived as if they were paintings, to be hung on the wall similar to the Japanese

Kakemono as Lidia Morelli says (

Morelli 1932f), Fides experiments most in the designs for other decorative elements creating diverse solutions with various techniques.

By observing these designs, one can understand the great variety in the repertory of this artist and decorator: ranging from second Futurism and aeropainting, such as in the embroidery “in pieno”

La mareggiata (

Sea storm) (

Morelli 1931b,

1932b); to Art Deco, such as in models for lace (

Morelli 1932c,

1932d); from abstract symbols, such as in the embroideries for tablecloths (

Morelli 1932a,

1932e) or geometric patterns for cushions realized with quiltwork (

G. N. 1932); to surrealistic evocations, such as in the table runners (

Morelli 1931c).

Lidia Morelli appreciated Fides’s ability to design embroideries and appliqués on fabrics, but she also admired her use of stencils and activity with the airbrush, “which gave the work an indescribable softness” (

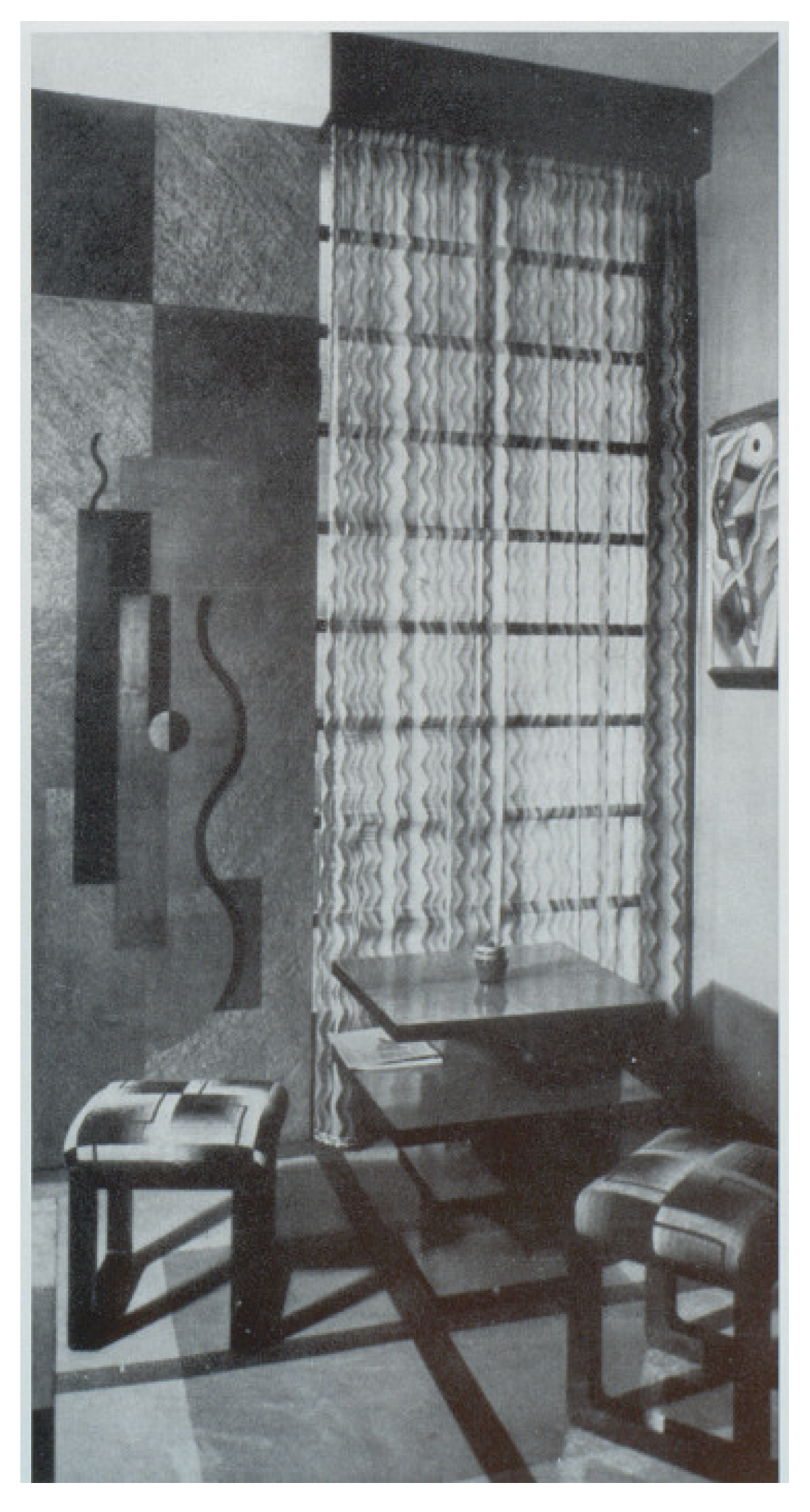

Morelli 1931c). “Concept, execution and materials in the artistry of Fides Testi correspond perfectly and complement each other”, wrote Lidia Morelli, who described the designs made with the airbrush as executed “with a dreamlike hand”, where “the light contours, the shadows and the shading seem to vanish and blend in with the color of the fabric” (

Morelli 1930). Morelli says that materials “correspond perfectly to the type of decoration which has been chosen”, from the lightest fabrics to the heaviest ones, and she demonstrates this statement with the “velvet moleskin” which was airbrushed with “very modern geometrical intersections” and used to upholster furniture designed by the architect Emanuele Cito Filomarino (

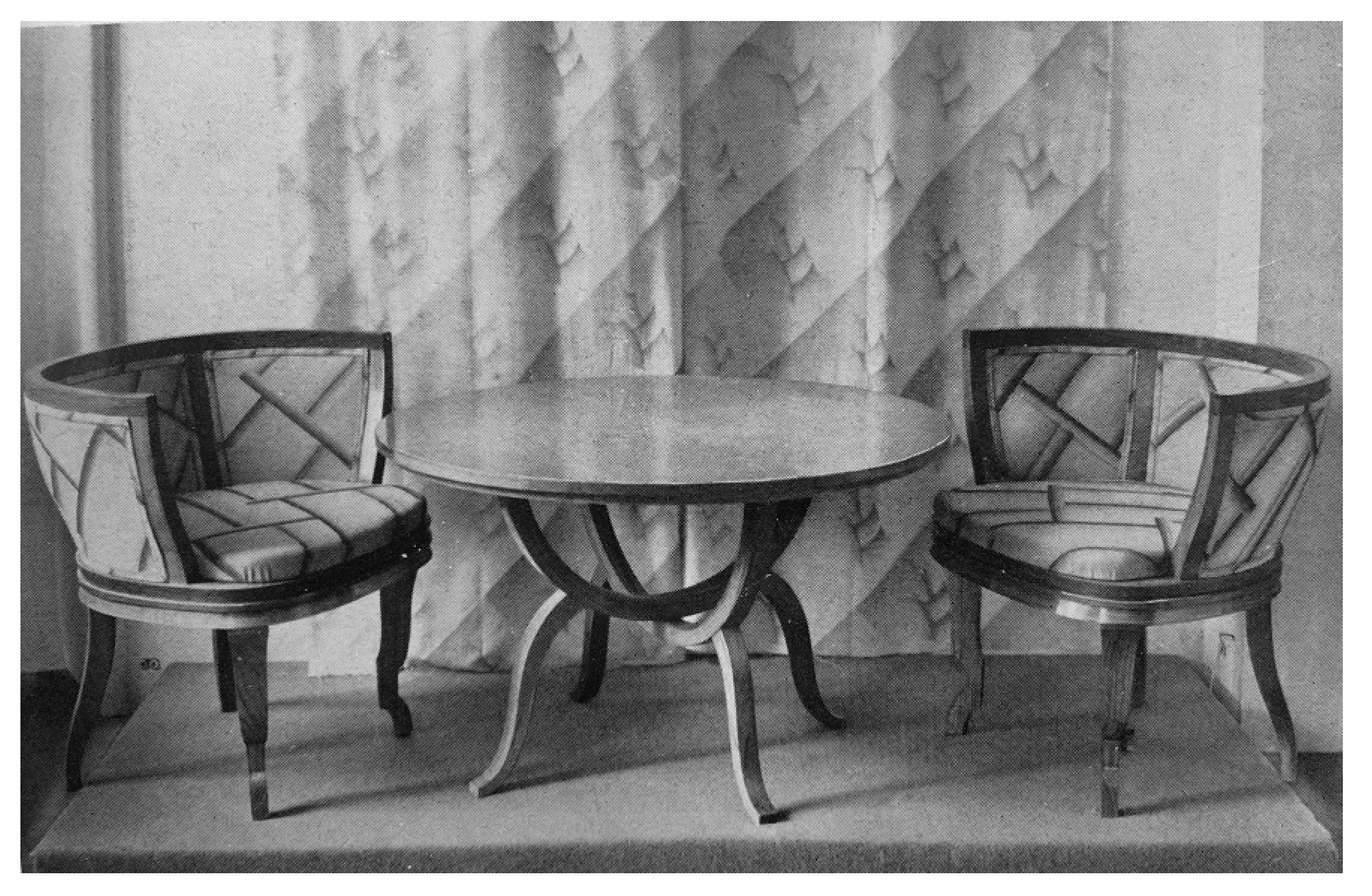

Morelli 1930) (

Figure 10).

Having lost most of the production of Fides, it is not possible to verify the claims made by Lidia Morelli, but we have an excellent example of this in the interior decoration of the Molle home, an apartment in Rome that was designed in 1932 by the architect Vittorio Morpurgo (

Maino 2009). The curtains of the bedroom-wardrobe of Mrs. Molle were the same as those made in 1930 for the Ente Nazionale delle Piccole Industrie exhibition (National Institute of Small Industries), and is a rare example of fabrics that have survived from this era. They demonstrate the quality and the shades of pink and green that, at the time, met with considerable success and were often reproduced

17 (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11); the area of the apartment with the bar seems to exemplify the correspondence between materials and function, as mentioned by Lidia Morelli: from the rough hemp covering of the bar decorated by Fides following a design of Morpurgo with glasses and shakers to the soft curtains decorated with a checkerboard pattern of shaded areas and wavy symbols (

Figure 12).

These curtains, like the ones in the little girl’s room in the Molle home with blue checks and checks with flowers, coordinated with the blankets on the bed, confirm the importance of this decorative element in the work of Fides, in quantitative and qualitative terms. She executed unique single pieces and made designs for mass production, working both as the creator of decorations as well as the executor of the designs of other artists. As a designer she found in curtains a particularly fertile field for experimentation with the use of the airbrush. The patterns, unbounded by the dimensions of a painting recognizable in the decorative panels, asserted “the extremely modern vivid imagination of the artist” (

Morelli 1931c), such as in

La caccia alla volpe (Fox Hunt), with a vivacious narrative bent, or in

Il muro vecchio (The Old Wall), more ironic than melancholic, which plays with the challenge of representing a wall on a curtain (both in

Morelli 1930,

1931a). Similarly significant was her participation in projects for Ente Nazionale delle Piccole Industrie (National Institute of Small Industries) with the curtains made in 1933 (

V Triennale di Milano. Esposizione Internazionale delle Arti Decorative e Industriali Moderne e Dell’architettura Moderna. Maggio-Settembre 1933 1933) and in 1936 (

L’artigianato d’Italia alla Sesta Triennale di Milano, Maggio-Ottobre 1936 1936;

Oggetti d’arte decorativa alla Triennale. La sezione dell’ENAPI 1936), which represented indispensable elements of modern décor.

Curtains were related to a new use of light and color in the home, exemplifying the new taste when they were simplified in their shape, with masses of colors both flat and delicately shaded following geometric designs.

“In a modern house, the curtains are not just a necessary accessory to the decoration”, we read in a 1930 issue in the magazine

La casa bella, but an element that is part of the rules of hygiene and illumination, and responds to the principles of the new aesthetics: “especially artificial silk which has been treated with the spray technique like the exquisite fabrics displayed at Monza in the Ente Nazionale Piccole Industrie rooms […] is the material which has prevailed at present” (

Le tende 1930) (

Figure 10).

It is therefore clear how Fides’ work played a significant role in the aesthetics of the Italian house of the 1930s. Although airbrush constitutes more of a “painting” technique than one that is strictly “textile” it does represent an important chapter in the history of textile taste in Italy during the 1930s.